Abstract

Pathological gambling is a psychiatric disorder and the first recognized behavioral addiction, with similarities to substance use disorders but without the confounding effects of drug-related brain changes. Pathophysiology within the opioid receptor system is increasingly recognized in substance dependence, with higher mu-opioid receptor (MOR) availability reported in alcohol, cocaine and opiate addiction. Impulsivity, a risk factor across the addictions, has also been found to be associated with higher MOR availability. The aim of this study was to characterize baseline MOR availability and endogenous opioid release in pathological gamblers (PG) using [11C]carfentanil PET with an oral amphetamine challenge. Fourteen PG and 15 healthy volunteers (HV) underwent two [11C]carfentanil PET scans, before and after an oral administration of 0.5 mg/kg of d-amphetamine. The change in [11C]carfentanil binding between baseline and post-amphetamine scans (ΔBPND) was assessed in 10 regions of interest (ROI). MOR availability did not differ between PG and HV groups. As seen previously, oral amphetamine challenge led to significant reductions in [11C]carfentanil BPND in 8/10 ROI in HV. PG demonstrated significant blunting of opioid release compared with HV. PG also showed blunted amphetamine-induced euphoria and alertness compared with HV. Exploratory analysis revealed that impulsivity positively correlated with caudate baseline BPND in PG only. This study provides the first evidence of blunted endogenous opioid release in PG. Our findings are consistent with growing evidence that dysregulation of endogenous opioids may have an important role in the pathophysiology of addictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Pathological gambling (PG) is a psychiatric disorder characterized by a pre-occupation with thoughts of gambling, repeated attempts to reduce or quit, debt and/or illegal activity, and disruption of personal relationships and/or employment. PG has been estimated to affect between 0.2 and 5.3% of the adult population worldwide (Hodgins et al, 2011). Originally classified as an ‘Impulse Control Disorder’ in DSM-IV, PG has recently been reconceptualized as a ‘behavioral addiction’ (Bowden-Jones and Clark, 2011), now classified as a ‘Substance-Related and Addictive Disorder’ in DSM-5 due to the observed similarities with substance addiction. These include clinical and etiological features such as abnormal reward sensitivity (van Holst et al, 2010), disadvantageous decision making and diminished behavioral inhibition (Verdejo-Garcia et al, 2008). PG constitutes a useful model to provide broader insights into the core brain processes of addictive disorders as it does not involve the confounding effects of excessive and chronic substance use on brain function.

Psychological treatments including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are currently the first-line therapies for PG; however, these are associated with only a partial response and short-term benefits (Cowlishaw et al, 2012). There has been less exploration of the neuropharmacology of PG, despite evidence from preliminary trials that opiate antagonists may be beneficial (Potenza, 2008). There is a wealth of evidence indicating a key role for the opioidergic system in substance dependence, as well as in related constructs such as reward and impulsivity. The opiate antagonists, naltrexone and nalmefene, are also proven treatments for addictions, particularly alcoholism (Lingford-Hughes et al, 2012). Endogenous opioids in the brain comprise a number of peptides (β-endorphins, dynorphins, enkephalins) and their receptors (mu, kappa, delta, respectively) are widely distributed throughout the brain. Mu-opioid receptors (MOR) have a key role in mediating rewarding effects of opiates and are most dense in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and amygdala (Mansour et al, 1988).

Evidence of a dysregulated opioid system in alcohol, cocaine, and opiate addiction has been shown using positron emission tomography (PET) with the selective MOR agonist radioligand [11C]carfentanil, which has greater selectivity of the order 100-fold for MOR over other subtypes (Subramanian et al, 2000; Titeler et al, 1989) or the non-selective tracer [11C]diprenorphine. In these studies, higher MOR availability is consistently reported (Gorelick et al, 2005; Heinz et al, 2005; Williams et al, 2007, 2009; Zubieta et al, 1996). Higher MOR availability is also associated with craving, which might contribute to the high rates of relapse during early abstinence (Gorelick et al, 2005). It has therefore been argued that as higher MOR availability is seen across addictions to substances with differing pharmacology, these changes are fundamental to addiction rather than substance-specific (Williams et al, 2009). Higher MOR availability, measured with [11C]carfentanil PET may reflect either an increase in receptor density or a reduction in endogenous β-endorphin levels to which [11C]carfentanil is sensitive (Colasanti et al, 2012; Mick et al, 2014). A reduction in endogenous β-endorphin levels would be consistent with the concept that addiction vulnerability is associated with an ‘opioid-deficient’ state, which is compensated for by drug taking (Ulm et al, 1995). Consistent with this hypothesis, individuals with an elevated risk of alcoholism, and a heightened response to alcohol, have been shown to have lower basal levels of plasma β-endorphin (Gianoulakis, 1996).

Previously, we have shown in two independent healthy participant (HV) cohorts that an oral d-amphetamine (0.5 mg/kg) challenge releases endogenous opioids as indicated by a reduction in [11C]carfentanil binding (Colasanti et al, 2012; Mick et al, 2014). This approach allows us for the first time to directly measure opioid release in vivo in the brain of individuals with addictive disorders. In the present study, we used this technique to examine both baseline MOR availability and endogenous opioid release in PG. Previous studies using [11C]carfentanil have shown excellent reproducibility of [11C]carfentanil-binding parameter estimates (Hirvonen et al, 2009). Given the similarities in behavior between PG and substance addiction, we hypothesized that PG would be associated with higher baseline MOR levels. On the basis of the ‘opioid-deficient’ hypothesis in alcoholism, we hypothesized that endogenous opioid release after amphetamine in PG would be attenuated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Fifteen males with PG were recruited from the National Problem Gambling Clinic, Central North West London NHS Foundation Trust, UK. One participant’s PET data were not quantifiable owing to technical issues, leaving 14 PG (mean age±SD 34.3±7.65 years, three smokers). Fifteen male age-matched HV (34.5±8.77 years, two smokers) have been previously described in our original (Colasanti et al, 2012) six who received ‘high dose’ amphetamine and second cohort (Mick et al, 2014). Only men were studied owing to the small number of women in treatment at the clinic, at 7% of clinic attendees. Participants’ current/previous medical/mental health as well as history of alcohol, tobacco, and other substance use were assessed by trained psychiatrists using Mini Psychiatric Interview International (MINI-5) (Sheehan et al, 1998). HV with current or previous psychiatric disorders were excluded. In PG, past depression and anxiety was allowed, as these are common comorbidities; current depression or anxiety was excluded. Current or past history of substance abuse or dependence including alcohol but except nicotine, was an exclusion criterion; previous recreational drug use was allowed (>10 times in lifetime: one HV: cannabis; two PG: cannabis and cocaine). Participants were excluded if they drank more than 21 UK units of alcohol (166 g) per week. Other drug use (except tobacco) was not allowed 2 weeks prior and during the study. This was confirmed on study days by negative urine drug screen testing (cocaine, amphetamine, THC, methadone, opioids, benzodiazepines) and participants also breathalyzed negative for alcohol. Smoking was not allowed 1 h before each scan. All the participants had laboratory and ECG results within normal range; none were taking regular medication.

PG were recruited either before or during an 8-week course of CBT and all had a recent history of active gambling; ‘days of abstinence’ ranged between 3 and 128 days (mean±SD 47±40.8). DSM-IV diagnosis of PG was confirmed with the Massachusetts Gambling Screen (Shaffer et al, 1994; MAGS; mean±SD 7±1.9) corroborated by the Problem Gambling Severity Index (Ferris and Wynne, 2001; PGSI; mean±SD 18±5.2). The Gambling Craving Scale (Young and Wohl, 2009; GACS) measured baseline craving for gambling on the study day. Depression was assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and anxiety with Spielberger Trait inventory (STAI). To assess impulsivity, the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (Cyders et al, 2007) was used with its five subscales: Negative Urgency (NU), Positive Urgency (PU), Lack of Planning (LoP), Lack of Perseverance (LoPe), and Sensation Seeking (SS).

On the screening day, participants underwent structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and performed a computerized neurocognitive assessment; these results will be reported elsewhere.

Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The study was approved by the West London Research Ethics Committee and the Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee, UK.

Procedure

PET imaging procedures were identical to our previous studies with [11C]carfentanil (Colasanti et al, 2012; Mick et al, 2014). Briefly, participants underwent two [11C]carfentanil PET scans, one before and one 3 h following an oral administration of 0.5 mg/kg of d-amphetamine. Nine HV underwent both PET scans on the same day. For six HV, the post-amphetamine scan was acquired on a different day for logistic reasons; none of them received two doses of amphetamine. The average time between pre- and post scans in these cases was 8 days (range: 1–36 days). For PG, 13 out of 14 participants had their pre- and post-amphetamine PET scans on the same day. One PG participant had his scans 8 days apart. The oral d-amphetamine was administered 3 h before the post- amphetamine scan, after a light meal, based upon peak amphetamine plasma levels (Mick et al, 2014). Blood samples to assess plasma levels were obtained pre-dosing; 1; 2; 3, and 4.5 h post dosing.

Subjective responses to the amphetamine challenge were rated using the simplified version of the Amphetamine Interview Rating Scale (SAIRS) (Van Kammen and Murphy, 1975), consisting of self-ratings for euphoria, restlessness, alertness, and anxiety (from 1 (least ever felt) to 10 (most ever felt)). It was administered after the pre-amphetamine scan, 15 min pre-dosing and post dosing at 5 min, 1, 2, and 3 h (just before the post-amphetamine scan) and 4.5 h.

PET and MR Imaging

As previously (Colasanti et al, 2012; Mick et al, 2014), dynamic [11C]carfentanil PET scans were acquired on a HiRez Biograph 6 PET/CT scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Dynamic emission data were collected continuously for 90 min (26 frames, 8 × 15 s, 3 × 60 s, 5 × 120 s, 5 × 300 s, 5 × 600 s), following an intravenous injection of 217±66.07 (mean±SD) MBq of [11C]carfentanil in HV and 211±58.42 MBq in PG. All the participants underwent a T1-weighted structural MRI (Magnetom Trio Syngo MR B13 Siemens 3T; Siemens AG, Medical Solutions). All the structural images were reviewed by an experienced neuroradiologist for unexpected findings of clinical significance. None were observed; however, one PG participant was excluded owing to the inaccurate spatial normalization of PET data into standard space using the structural MR data.

Image Analysis

As described previously (Colasanti et al, 2012; Mick et al, 2014), pre-processing of images and PET modeling were carried out using MIAKAT, an analysis tool developed at Imanova. After frame-by-frame motion correction of the dynamic PET data, region-of-interest (ROI) time-activity data were sampled using the CIC neuroanatomical atlas (Tziortzi et al, 2011). This was applied to the PET image by non-linear deformation parameters derived from the transformation of the structural MRI into standard space.

Nine grey-matter-masked ROIs were chosen a priori, as brain areas with a high density of MOR, with significant amphetamine-induced reductions of [11C]carfentanil BPND, and relevant to addiction—the caudate, putamen, thalamus, cerebellum, frontal lobe, nucleus accumbens, anterior cingulate, amygdala, and insula cortices. A tenth region of interest, hypothalamus, where endorphin cell bodies are located, was manually defined on the MRI of each subject according to anatomical reference as described previously (Colasanti et al, 2012; Tziortzi et al, 2011). BPND was quantified regionally using the simplified reference tissue model with occipital lobe as the reference region (Colasanti et al, 2012). Endogenous opioid release was indexed as the fractional reduction in [11C]carfentanil BPND following the d-amphetamine:

Statistical Analysis

Demographic differences between groups, and injected mass/activity, were analyzed using independent-samples t-tests (2-tailed). An omnibus mixed-model ANOVA tested BPND as a function of Scan (pre-amphetamine vs post-amphetamine), ROI (10 levels) and Group (HV, PG). For analysis of simple main effects for our hypotheses concerning opioid release, we calculated percentage changes in [11C]carfentanil BPND (%ΔBPND) from pre- to post-amphetamine scans. The subjective responses to the amphetamine challenge were analyzed using mixed-model ANOVAs based on the change from baseline values, with Group (HV, PG) as a between-subjects factor and Time (60, 120, 180, 270 min) as a repeated-measures factor. Given the ordinal relationship in the within-subjects factor (Time), we tested the linear and quadratic terms. For correlational analyses, we calculated a summary Δscore for subjective responses based on the SAIRS and SSAI, from the subjective peak minus the baseline. We tested for correlations between BPND, subjective effects, and plasma amphetamine concentrations, using the subjective Δscores and baseline BPND and regional %ΔBPND. Associations between MOR BPND and impulsivity measures were verified through Pearson’s r correlation test. Percentile bootstrap (1000 replications) was used to estimate 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the correlation coefficient (Fethney, 2010). All data were normally distributed as determined by visual inspection as well as using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests for normality. All statistical comparisons were assessed using SPSS version 20.0; p<0.05 was accepted as a nominal level of statistical significance.

RESULTS

Pharmacokinetic Amphetamine Plasma Samples

At 3 h post dosing, just before the post-amphetamine scan, the mean plasma amphetamine concentrations reached a peak of 86.8±18.2 ng/ml (mean±SD) in HV and 87.2±10.3 ng/ml in PG, with no significant group differences in amphetamine absorption (t21=0.06, p=0.951). There were no significant correlations between amphetamine plasma concentrations and baseline [11C]carfentanil BPND or %ΔBPND.

Injected Mass and Radioactivity

In HV, the mean injected [11C]carfentanil mass for scan 1 was 1.02±0.52 μg and scan 2 was 1.08±0.52 μg (t14=−2.51, p=0.025). For PG, the mean injected [11C]carfentanil mass was 1.53±0.27 μg for scan 1 and 1.45±0.20 μg for scan 2 (t13=2.39, p=0.032). There were also significant differences between groups in masspre (p=0.003) and masspost HV/PG (p=0.015). There were no significant differences in injected activity between or within groups (HV: pre 225.1±65.0 MBq, post 208.9±67.1 MBq; PG: pre 207.9±67.7 MBq; post 214.0±49.2 MBq). To rule out any mass effect, we confirmed there were no significant correlations between masspre and baseline [11C]carfentanil BPND (p=0.851) or masspost and post-amphetamine [11C]carfentanil BPND (p=0.918).

Clinical Variables

There were no differences between PG and HV in age, IQ, smoking, and alcohol consumption; however, PG scored higher on measures of depression and anxiety though none reached a clinical threshold (see Table 1).

[11C]carfentanil Binding

The omnibus ANOVA for BPND revealed a number of significant effects. There was a significant main effect of ROI (F(9,243)=248.5, p<0.001) indicating reliable differences in [11C]carfentanil binding across the 10 brain regions, with greatest binding in the nucleus accumbens and thalamus (see Table 2). There was a significant main effect of Scan (F(1,27)=26.4, p<0.001), and a Scan × ROI interaction (F(2.04,55.2)=3.07, p=0.053) consistent with amphetamine-induced opioid release that varied in extent across brain regions (see Figure 1). There was a significant Scan × Group interaction (F(1,27)=7.07, p=0.013), which is explored further below. The three-way Scan × Group × ROI interaction was not statistically significant (F(2.04,55.2)=0.37, p=0.696).

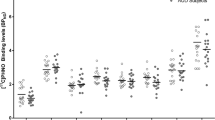

Percentage change (mean and SD) of [11C]carfentanil BPND from pre-amphetamine to post-amphetamine scan in HV and PG. There was a significant difference between groups in the frontal lobe, insula, anterior cingulate, putamen and cerebellum.

To directly test our hypotheses, first, we tested for group differences in baseline MOR levels using a Group × ROI model on the pre-amphetamine BPND levels. There was no significant main effect of Group (F(1,27)=0.01, p=0.923), or Group × ROI interaction (F(3.8, 103.8)=0.73, p=0.566). Thus, the hypothesis that PG would be associated with higher MOR levels was not supported.

Second, we confirmed that the amphetamine challenge led to significant reductions in [11C]carfentanil BPND in the HV group, using a Scan × ROI model. There was a significant main effect of Scan (F(1,14)=36.9, p<0.001), with no reliable Scan × ROI interaction (F(2.03,28.4)=2.18, p=0.132), driven by significant reductions in eight (caudate, putamen, thalamus, cerebellum, frontal lobe (includes dorsolateral, medial, and orbitofrontal cortices), nucleus accumbens, anterior cingulate, insular cortices of the 10 (amygdala, hypothalamus) regions of interest (see Table 2). Mean regional percentage reduction in BPND ranged between −4.9 and −7.7% (see Figure 1). There were no regions where increased BPND was observed. A post hoc analysis showed no impact of the interval between first and second scan on the results of the intervention (r=−0.11, p=0.563), and no difference between the HV BPND changes on same (n=10) and different (n=5) days (t=0.69, p=0.95). There were no differences between ‘past drug users’ (>10 times in lifetime) and ‘non-past drug users’ in either baseline [11C]carfentanil BPND (t=−0.97, p=0.34) or %ΔBPND (t=−0.24, p=0.98).

Third, to test whether PG was associated with blunted opioid release and decompose the Scan × Group interaction in the omnibus model, we ran a Group × ROI model on the %ΔBPND scores. There was a significant main effect of Group (F(1,27)=8.31, p=0.008) without a reliable Group × ROI interaction (F(1.9,50.7)=0.36, p=0.684). As such, the blunting of opioid release did not vary reliably across the 10 brain regions. The PG group showed significantly attenuated opioid release in the putamen (t27=2.85, p=0.008), cerebellum (t27=2.51, p=0.018), frontal lobe (t27=3.76, p=0.001), anterior cingulate (t27=4.17, p<0.001) and insula (t27=3.08, p=0.005).

Effects of Amphetamine on Subjective Responses

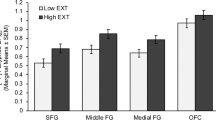

The subjective effects from the oral amphetamine were mild (see Figure 2). For euphoria ratings, an ANOVA of change from baseline values indicated no overall change in euphoria (main effect of Time: F(2.5,66.6)=1.09, p=0.353) but a significant quadratic term for the Group × Time interaction (F(1,27)=5.06, p=0.033), such that amphetamine-induced euphoria was diminished in the PG group at the 120 (p=0.047) and 180 (p=0.042) minute time points around the peak response (see Figure 2a). For alertness ratings, ANOVA yielded no overall change in alertness (main effect of Time: F(2.1,58.0)=0.86, p=0.435) but a significant Group × Time interaction (F(2.1,58.0)=3.54, p=0.032; see Figure 2b), with a diminished response in the PG group at 60 (p=0.009), 120 (p=0.007) and 180 (p=0.007) minutes. For anxiety ratings, there was an overall decrease in anxiety (F(3,81)=4.44, p=0.006) and a significant Group × Time interaction (F(3,81)=3.70, p=0.015) although groups did not differ significantly at any individual time point. There were no effects on restlessness (main effect of Time: F(1.8,49.5)=0.45, p=0.624; Group × Time F(1.8,49.5)=1.21, p=0.304).

Changes in subjective amphetamine effects measured at four time points (minutes). (a) Amphetamine-induced euphoria was significantly diminished in the pathological gamblers group at 120 and 180 min. (b) For alertness scores, there were significantly diminished responses in the pathological gamblers group at 60, 120, and 180 min. (c, d) Groups did not differ significantly at any individual time point for anxiety or restlessness.

Relationship Between PET Measures and Clinical/ Impulsivity Scores

None of the clinical variables assessing severity of problem gambling (PGSI), craving to gamble (GACS), depression (BDI), anxiety (STAI, SSAI), alcohol use (AUDIT), or ‘days of abstinence’ were significantly correlated with baseline [11C]carfentanil BPND or %ΔBPND.

PG showed significantly higher scores in UPPS-P NU and PU subscales compared with HV (see Table 1). An exploratory analysis of HV and PG groups separately revealed a significant positive correlation between NU and baseline [11C]carfentanil BPND in the caudate in PG (r=0.638; p=0.014). There were no significant correlations with baseline BPND in HV.

DISCUSSION

Using [11C]carfentanil PET, we demonstrate here evidence of blunted endogenous opioid release to an oral amphetamine challenge in PG compared with HV, whereas there was no difference in baseline MOR availability. Our hypotheses for this study were predicated on the view that as a behavioral addiction, PG would have similar neurobiological signature to that established for substance addictions. Our observation of blunted opioid release is consistent with the broader ‘reward deficiency hypothesis’. Our data are consistent with lower baseline endorphin levels reported in individuals with a positive family history of alcoholism compared with those with no family history, though increased endorphin release was seen after exposure to alcohol (Gianoulakis, 1996). Thus a dysregulated endorphin system appears to be present in behavioral and substance addictions. However, the hypothesis of higher baseline MOR availability in PG was not supported, in contrast to consistent findings in substance addiction. Similar to past work, we also found relationships between [11C]carfentanil BPND binding and trait impulsivity, but no relationships with other clinical variables.

Our key finding of a blunted release of endogenous opioid in PG following the oral amphetamine challenge strongly suggests a dysregulated opioid system in this disorder. Other studies measuring plasma β-endorphin during a gambling task are inconsistent with increase, no change, or blunted response reported (Blaszczynski et al, 1986; Meyer et al, 2004; Shinohara et al, 1999). The blunted opioid release in our study was accompanied by diminished subjective euphoria and alertness in PG in response to the amphetamine challenge, and was not explained by differences in plasma amphetamine levels between the groups. Another study has reported similarly increased euphoria in PG and controls following a similar oral amphetamine challenge to ours (0.4 vs 0.5 mg/kg) in combination with a dopaminergic PET tracer (Boileau et al, 2013). There are a number of pertinent differences that may underlie these contrasting effects. The Addiction Research Center Inventory used by Boileau assays a broader range of subjective responses than the SAIRS we used. In addition, our samples were all in treatment and had not gambled recently, whereas the participants in Boileau’s study were non-treatment-seeking (Boileau et al, 2013). Another factor that may have moderated the response was that oral amphetamine was nonsalient as both PG and HV had limited or no experience of such stimulants. Thus our blunted response is consistent with other addiction studies, which have shown that responses to a nonsalient ‘reward’ are blunted compared with salient ones (Lubman et al, 2008).

Concerning baseline MOR availability, our hypothesis that individuals with PG would show higher MOR availability was based on findings in individuals dependent on substances with differing pharmacologies, that is, cocaine (Zubieta et al, 1996), alcohol (Heinz et al, 2005; Williams et al, 2009), or heroin (Williams et al, 2007). Relationships have been described between higher MOR availability and greater craving in alcohol and cocaine addiction (Gorelick et al, 2005; Heinz et al, 2005; Williams et al, 2009; Zubieta et al, 1996). Such a relationship provides a potential mechanism for the clinical efficacy of opioid antagonists, naltrexone and nalmefene, in treating alcoholism (Lingford-Hughes et al, 2012). These medications have also shown efficacy in treating PG, which provides another rationale for predicting higher MOR availability (Ghitza et al, 2010). However, we did not observe any group difference in MOR availability or any relationship with craving in our PG sample. A key clinical variable that may impact on opioid receptor availability is abstinence. In cocaine addiction, higher levels of MOR availability are related to relapse and levels may reduce over time (Ghitza et al, 2010; Gorelick et al, 2008; Zubieta et al, 1996), though no changes in availability have been reported in alcoholism up to 3 months of sobriety (Heinz et al, 2005; Williams et al, 2009). Our PG were in treatment and abstinent at the time of scanning, so the influence of abstinence on MOR in behavioral addiction requires further investigation.

Consistent with previous research, we found significantly higher impulsivity scores using the UPPS scale in PG compared with HV (Clark et al, 2012; Forbush et al, 2008; Fuentes et al, 2006; Michalczuk et al, 2011). An exploratory analysis revealed that in PG, baseline [11C]carfentanil BPND in the caudate was positively correlated with the UPPS Negative Urgency subscale, which relates to the tendency towards impulsive behavior while experiencing negative affect (Whiteside and Lynam, 2001). This association was not observed in the HV group. These data also lend further support to a role of the endogenous opioid system in impulsive behaviors, particularly mood-related impulsivity, which is consistent with the proposed role for opioid system in emotion (Zubieta et al, 2003).

Although the efficacy of opiate antagonists in some people with PG was first reported over a decade ago, our study is the first to assess the integrity of the opioid system in PG, by imaging MOR availability and opioid release. Past work links the endogenous opioid system with pleasure, urges, and impulsivity (Love et al, 2009). For instance in HV, the opiate antagonist, naloxone, attenuated the fMRI response in the medial prefrontal cortex to monetary wins in a gambling task and increased responses to monetary losses in insula and anterior cingulate (Petrovic et al, 2008). The opiate antagonists, naltrexone and nalmefene were investigated as treatment for PG based on preclinical evidence of opioid involvement in urge and motivation and their efficacy in alcoholism (Grant et al, 2014; Potenza, 2008). A recent meta-analysis reported a small but significant effect of opiate antagonists though noted earlier studies were more likely to report efficacy (Bartley and Bloch, 2013). PG who respond to opioid antagonists report significant reduction in gambling urges, particularly in those with a family history of alcohol dependence (Grant et al, 2008; Potenza, 2008). In our sample, only one PG had a family history of alcoholism so we were unable to explore this further. The underlying mechanism for clinical efficacy of opioid antagonists in alcoholism is generally described as blocking the increased MOR and β-endorphin stimulation of MOR in mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway thus reducing activity and the rewarding effects of alcohol and craving (Johnson and North, 1992). Given our observation that MOR availability is unchanged in PG, the mechanism of action for opioid antagonists may therefore involve other opioid receptors such as kappa (Votinov et al, 2014) or processes other than those involved in pleasure and reward, such as impulsivity.

Dysregulation between opioid and dopamine transmission is likely to underlie our blunted opioid release in PG. Studies implicate a role for DRD2/3 in regulating endorphin release (Doron et al, 2006; Soderman and Unterwald, 2009). A role for the hypothalamus is probable since opioid projections originate from here to modulate dopaminergic neuronal activity in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) (Bourdy and Barrot, 2012). Concerning the dopaminergic system in PG, increased dopamine release in PG to a similar amphetamine challenge has been reported alongside no difference in dopamine receptor availability using [11C]PHNO PET (Boileau et al, 2013). In this study, [11C]PHNO binding in the hypothalamus was not assessed in PG and since we found increased [11C]PHNO binding in the hypothalamus in alcoholism with no differences elsewhere in the brain, it would be interesting to know if [11C]PHNO in the hypothalamus in PG was similarly increased (Erritzoe et al, 2014). Further investigation of dopamine–opioid interactions is warranted to characterize the sensitivity of dopaminergic system and whether there is reduced function of POMC-ergic hypothalamic neurons in PG.

In summary, we provide here the first evidence of a dysregulated opioid system in PG with blunted amphetamine-induced opioid release in the presence of normal MOR availability. The evidence from PET imaging of dopaminergic and opioid systems suggest that this behavioral addiction may differ from substance addiction with regard to receptor availability and release of endogenous neurotransmitters. Characterizing dopamine–opioid interactions will inform our understanding of substance and behavioral addictions as these neurotransmitter systems are critically involved. The reclassification of PG (and renaming to disordered gambling) in DSM-5 was based on evidence from epidemiological, clinical, and neurobiological data demonstrating similarities between PG and substance addiction (Clark and Limbrick-Oldfield, 2013). Therefore, further investigation of the neurobiology of PG with direct comparisons with other addictions is required to characterize their comparative neurobiology.

Funding and Disclosure

This study was funded by the Medical Research Council- MRC G1002226. Anna Ramos has received financial support with a scholarship from CAPES (Process number: PDSE 99999.014476/2013-04). Dr Colasanti has been supported by a GSK/Wellcome Trust Fellowship in Translational Medicine and Therapeutics awarded through Imperial College London. The National Problem Gambling Clinic (Dr Bowden-Jones) receives some of its funding from the Responsible Gambling Trust. Dr Rabiner is a consultant for Lightlake Pharmaceutical, GSK, AbbVie, Teva, and a shareholder in GSK. Dr Waldman has received honoraria from Bayer, Novartis, and GSK, and has been a consultant for Bayer. Dr Stokes has received an honorarium from Indivior. Dr Clark has provided consultancy work for Cambridge Cognition Ltd, and the Centre for Gambling Research at UBC is funded by the Province of British Columbia and the British Columbia Lottery Corporation. Professor Gunn is a consultant for GSK, Abbvie, and UCB. Professor Lingford-Hughes has received research funding/support from Lundbeck, GSK, and honoraria for talks from Lundbeck. All the other authors report no conflict of interest.

References

Bartley CA, Bloch MH (2013). Meta-analysis: pharmacological treatment of pathological gambling. Expert Rev Neurother 13: 887–894.

Blaszczynski APW, Simon W, McConaghy Neil (1986). Plasma endorphin levels in pathological gambling. J Gambl Behav 2: 3–14.

Boileau I, Payer D, Chugani B, Lobo DS, Houle S, Wilson AA et al (2013). In vivo evidence for greater amphetamine-induced dopamine release in pathological gambling: a positron emission tomography study with [C]-(+)-PHNO. Mol Psychiatry 19: 1305–1313.

Bourdy R, Barrot M (2012). A new control center for dopaminergic systems: pulling the VTA by the tail. Trends Neurosci 35: 681–690.

Bowden-Jones H, Clark L (2011). Pathological gambling: a neurobiological and clinical update. Br J Psychiatry 199: 87–89.

Clark L, Limbrick-Oldfield EH (2013). Disordered gambling: a behavioral addiction. Curr Opin Neurobiol 23: 655–659.

Clark L, Stokes PR, Wu K, Michalczuk R, Benecke A, Watson BJ et al (2012). Striatal dopamine D(2)/D(3) receptor binding in pathological gambling is correlated with mood-related impulsivity. Neuroimage 63: 40–46.

Colasanti A, Searle GE, Long CJ, Hill SP, Reiley RR, Quelch D et al (2012). Endogenous opioid release in the human brain reward system induced by acute amphetamine administration. Biol Psychiatry 72: 371–377.

Cowlishaw S, Merkouris S, Dowling N, Anderson C, Jackson A, Thomas S (2012). Psychological therapies for pathological and problem gambling. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11: CD008937.

Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C (2007). Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychol Assess 19: 107–118.

Doron R, Fridman L, Yadid G (2006). Dopamine-2 receptors in the arcuate nucleus modulate cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuroreport 17: 1633–1636.

Erritzoe D, Tziortzi A, Bargiela D, Colasanti A, Searle GE, Gunn RN et al (2014). In vivo imaging of cerebral dopamine D3 receptors in alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacology 39: 1703–1712.

Ferris J, Wynne H (2001) Canadian Problem Gambling Index. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse: Ottawa, Ontario.

Fethney J (2010). Statistical and clinical significance, and how to use confidence intervals to help interpret both. Aust Crit Care 23: 93–97.

Forbush KT, Shaw M, Graeber MA, Hovick L, Meyer VJ, Moser DJ et al (2008). Neuropsychological characteristics and personality traits in pathological gambling. CNS Spectr 13: 306–315.

Fuentes D, Tavares H, Artes R, Gorenstein C (2006). Self-reported and neuropsychological measures of impulsivity in pathological gambling. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 12: 907–912.

Ghitza UE, Preston KL, Epstein DH, Kuwabara H, Endres CJ, Bencherif B et al (2010). Brain mu-opioid receptor binding predicts treatment outcome in cocaine-abusing outpatients. Biol Psychiatry 68: 697–703.

Gianoulakis C (1996). Implications of endogenous opioids and dopamine in alcoholism: human and basic science studies. Alcohol Alcohol 31 Suppl 1: 33–42.

Gorelick DA, Kim YK, Bencherif B, Boyd SJ, Nelson R, Copersino M et al (2005). Imaging brain mu-opioid receptors in abstinent cocaine users: time course and relation to cocaine craving. Biol Psychiatry 57: 1573–1582.

Gorelick DA, Kim YK, Bencherif B, Boyd SJ, Nelson R, Copersino ML et al (2008). Brain mu-opioid receptor binding: relationship to relapse to cocaine use after monitored abstinence. Psychopharmacology 200: 475–486.

Grant JE, Kim SW, Hollander E, Potenza MN (2008). Predicting response to opiate antagonists and placebo in the treatment of pathological gambling. Psychopharmacology 200: 521–527.

Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Schreiber LR (2014). Pharmacological treatments in pathological gambling. Br J Clin Pharmacol 77: 375–381.

Heinz A, Reimold M, Wrase J, Hermann D, Croissant B, Mundle G et al (2005). Correlation of stable elevations in striatal mu-opioid receptor availability in detoxified alcoholic patients with alcohol craving: a positron emission tomography study using carbon 11-labeled carfentanil. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62: 57–64.

Hirvonen J, Aalto S, Hagelberg N, Maksimow A, Ingman K, Oikonen V et al (2009). Measurement of central mu-opioid receptor binding in vivo with PET and [11C]carfentanil: a test-retest study in healthy subjects. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 36: 275–286.

Hodgins DC, Stea JN, Grant JE (2011). Gambling disorders. Lancet 378: 1874–1884.

Johnson SW, North RA (1992). Opioids excite dopamine neurons by hyperpolarization of local interneurons. J Neurosci 12: 483–488.

Lingford-Hughes AR, Welch S, Peters L, Nutt DJ (2012). BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: recommendations from BAP. J Psychopharmacol 26: 899–952.

Love TM, Stohler CS, Zubieta JK (2009). Positron emission tomography measures of endogenous opioid neurotransmission and impulsiveness traits in humans. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66: 1124–1134.

Lubman DI, Allen NB, Peters LA, Deakin JF (2008). Electrophysiological evidence that drug cues have greater salience than other affective stimuli in opiate addiction. J Psychopharmacol 22: 836–842.

Mansour A, Khachaturian H, Lewis ME, Akil H, Watson SJ (1988). Anatomy of CNS opioid receptors. TrendsNeurosci 11: 308–314.

Meyer G, Schwertfeger J, Exton MS, Janssen OE, Knapp W, Stadler MA et al (2004). Neuroendocrine response to casino gambling in problem gamblers. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29: 1272–1280.

Michalczuk R, Bowden-Jones H, Verdejo-Garcia A, Clark L (2011). Impulsivity and cognitive distortions in pathological gamblers attending the UK National Problem Gambling Clinic: a preliminary report. Psychol Med 41: 2625–2635.

Mick I, Myers J, Stokes PR, Erritzoe D, Colasanti A, Bowden-Jones H et al (2014). Amphetamine induced endogenous opioid release in the human brain detected with [11C]carfentanil PET: replication in an independent cohort. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 17: 2069–2074.

Petrovic P, Pleger B, Seymour B, Kloppel S, De Martino B, Critchley H et al (2008). Blocking central opiate function modulates hedonic impact and anterior cingulate response to rewards and losses. J Neurosci 28: 10509–10516.

Potenza MN (2008). Review. The neurobiology of pathological gambling and drug addiction: an overview and new findings. Philos TransR Soc Lond B Biol Sci 363: 3181–3189.

Shaffer HJ, Labrie R, Scanlan KM, Cummings TN (1994). Pathological gambling among adolescents: Massachusetts Gambling Screen (MAGS). J Gambl Stud 10: 339–362.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E et al (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 59 Suppl 20: 22–33.

Shinohara K, Yanagisawa A, Kagota Y, Gomi A, Nemoto K, Moriya E et al (1999). Physiological changes in Pachinko players; beta-endorphin, catecholamines, immune system substances and heart rate. Appl Human Sci 18: 37–42.

Soderman AR, Unterwald EM (2009). Cocaine-induced mu opioid receptor occupancy within the striatum is mediated by dopamine D2 receptors. Brain Res 1296: 63–71.

Subramanian G, Paterlini MG, Portoghese PS, Ferguson DM (2000). Molecular docking reveals a novel binding site model for fentanyl at the mu-opioid receptor. J Med Chem 43: 381–391.

Titeler M, Lyon RA, Kuhar MJ, Frost JF, Dannals RF, Leonhardt S et al (1989). Mu opiate receptors are selectively labelled by [3H]carfentanil in human and rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol 167: 221–228.

Tziortzi AC, Searle GE, Tzimopoulou S, Salinas C, Beaver JD, Jenkinson M et al (2011). Imaging dopamine receptors in humans with [11C]-(+)-PHNO: dissection of D3 signal and anatomy. Neuroimage 54: 264–277.

Ulm RR, Volpicelli JR, Volpicelli LA (1995). Opiates and alcohol self-administration in animals. J Clin Psychiatry 56 Suppl 7: 5–14.

van Holst RJ, van den Brink W, Veltman DJ, Goudriaan AE (2010). Why gamblers fail to win: a review of cognitive and neuroimaging findings in pathological gambling. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 34: 87–107.

Van Kammen DP, Murphy DL (1975). Attenuation of the euphoriant and activating effects of d- and l-amphetamine by lithium carbonate treatment. Psychopharmacologia 44: 215–224.

Verdejo-Garcia A, Lawrence AJ, Clark L (2008). Impulsivity as a vulnerability marker for substance-use disorders: review of findings from high-risk research, problem gamblers and genetic association studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32: 777–810.

Votinov M, Pripfl J, Windischberger C, Kalcher K, Zimprich A, Zimprich F et al (2014). A genetic polymorphism of the endogenous opioid dynorphin modulates monetary reward anticipation in the corticostriatal loop. PLoS One 9: e89954.

Whiteside SP, Lynam DR (2001). The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers Individ Dif 30: 669–689.

Williams TM, Daglish MR, Lingford-Hughes A, Taylor LG, Hammers A, Brooks DJ et al (2007). Brain opioid receptor binding in early abstinence from opioid dependence: positron emission tomography study. Br J Psychiatry 191: 63–69.

Williams TM, Davies SJ, Taylor LG, Daglish MR, Hammers A, Brooks DJ et al (2009). Brain opioid receptor binding in early abstinence from alcohol dependence and relationship to craving: an [11C]diprenorphine PET study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 19: 740–748.

Young MM, Wohl MJ (2009). The Gambling Craving Scale: psychometric validation and behavioral outcomes. Psychol Addict Behav 23: 512–522.

Zubieta JK, Gorelick DA, Stauffer R, Ravert HT, Dannals RF, Frost JJ (1996). Increased mu opioid receptor binding detected by PET in cocaine-dependent men is associated with cocaine craving. Nat Med 2: 1225–1229.

Zubieta JK, Ketter TA, Bueller JA, Xu Y, Kilbourn MR, Young EA et al (2003). Regulation of human affective responses by anterior cingulate and limbic mu-opioid neurotransmission. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60: 1145–1153.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the study participants and the clinical team at Imanova, Centre for Imaging Sciences. The research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Imperial Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mick, I., Myers, J., Ramos, A. et al. Blunted Endogenous Opioid Release Following an Oral Amphetamine Challenge in Pathological Gamblers. Neuropsychopharmacol 41, 1742–1750 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.340

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.340

This article is cited by

-

The Global Prevalence of Problem and Pathological Gambling and Its Associated Factors Among Individuals with Substance Use Disorders: A Meta-analysis

International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction (2023)

-

Risk for opioid misuse in chronic pain patients is associated with endogenous opioid system dysregulation

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

-

Blunted endogenous opioid release following an oral dexamphetamine challenge in abstinent alcohol-dependent individuals

Molecular Psychiatry (2020)

-

Reduced mu opioid receptor availability in schizophrenia revealed with [11C]-carfentanil positron emission tomographic Imaging

Nature Communications (2019)

-

Gambling disorder

Nature Reviews Disease Primers (2019)