Abstract

Neuroimaging studies in humans have demonstrated that inflammatory cytokines target basal ganglia function and presynaptic dopamine (DA), leading to symptoms of depression. Cytokine-treated nonhuman primates also exhibit evidence of altered DA metabolism in association with depressive-like behaviors. To further examine cytokine effects on striatal DA function, eight rhesus monkeys (four male, four female) were administered interferon (IFN)-α (20 MIU/m2 s.c.) or saline for 4 weeks. In vivo microdialysis was used to investigate IFN-α effects on DA release in the striatum. In addition, positron emission tomography (PET) with [11C]raclopride was used to examine IFN-α-induced changes in DA2 receptor (D2R) binding potential before and after intravenous amphetamine administration. DA transporter binding was measured by PET using [18F]2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-chlorophenyl)-8-(2-fluoroethyl)nortropane. Anhedonia-like behavior (sucrose consumption) was assessed during saline and IFN-α administration. In vivo microdialysis demonstrated decreased release of DA after 4 weeks of IFN-α administration compared with saline. PET neuroimaging also revealed decreased DA release after 4 weeks of IFN-α as evidenced by reduced displacement of [11C]raclopride following amphetamine administration. In addition, 4 weeks of IFN-α was associated with decreased D2R binding but no change in the DA transporter. Sucrose consumption was reduced during IFN-α administration and was correlated with decreased DA release at 4 weeks as measured by in vivo microdialysis. Taken together, these findings indicate that chronic peripheral IFN-α exposure reduces striatal DA release in association with anhedonia-like behavior in nonhuman primates. Future studies examining the mechanisms of cytokine effects on DA release and potential therapeutic strategies to reverse these changes are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Recent studies in laboratory animals have demonstrated that dopamine (DA) neurons play an important role in multiple depressive symptoms (Chaudhury et al, 2013; Tye et al, 2013). Similar findings suggest that impaired DAergic neurotransmission and morphometric changes in the striatum may contribute to major depression in humans (Bora et al, 2012; Dunlop and Nemeroff, 2007). One mechanism that may lead to basal ganglia DA changes in depression is inflammation. Work in our laboratory and others suggest that inflammatory cytokines may specifically target the basal ganglia and DA to mediate depressive symptoms (Felger and Miller, 2012). For example, positron emission tomography (PET) in interferon (IFN)-α-treated patients revealed increased glucose metabolism in the basal ganglia, consistent with Parkinson’s disease (Eidelberg et al, 1994), where it is believed to reflect increased oscillatory burst activity in relevant basal ganglia nuclei under inhibitory control of nigral DA input (Wichmann and DeLong, 2003). Of note, IFN-α-induced changes in basal ganglia glucose metabolism were correlated with fatigue (Capuron et al, 2007). Functional magnetic resonance imaging has also demonstrated decreased basal ganglia (striatal) activation to hedonic reward during IFN-α administration that correlated with reduced motivation (Capuron et al, 2012). Similar results were found with lipopolysaccharide, which decreased striatal activation in association with increased depressive symptoms (Eisenberger et al, 2010). In addition, typhoid vaccination has been shown to alter activity in the substantia nigra in relation to psychomotor slowing (Brydon et al, 2008). Finally, gray matter volume of the caudate has been shown to correlate with inflammatory gene expression in peripheral blood immune cells of depressed patients (Savitz et al, 2013). Taken together, these data suggest that inflammatory cytokines and cytokine inducers can affect the basal ganglia and related behaviors under multiple experimental conditions.

Regarding the mechanisms by which cytokines affect the basal ganglia, PET studies have revealed increased uptake and decreased turnover of the radiolabeled DA precursor [18F]fluorodopa (FDOPA) in the caudate and putamen of IFN-α-treated patients, which correlated with depressive symptoms (Capuron et al, 2012). In light of the role of basal ganglia DA in the regulation of motivation and motor activity, cytokine-induced changes in DA neurotransmission may mediate neurovegetative aspects of depression such as anhedonia, psychomotor retardation, and fatigue. We have previously demonstrated that nonhuman primates (rhesus monkeys) chronically administered IFN-α exhibit changes in psychomotor activity and depressive-like behavior, as well as activation of relevant cytokine networks and neuroendocrine responses, similar to IFN-α-treated humans (Felger et al, 2007; Felger and Miller, 2012). Interestingly, monkeys that display depressive-like behaviors in response to IFN-α administration exhibit reduced cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of the DA metabolites, homovanillic acid and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (Felger et al, 2007; Felger and Miller, 2012). Similar changes in DA metabolites have also been observed in the cerebrospinal fluid of IFN-α-treated humans (Felger and Miller, 2012).

To further examine the mechanisms of altered basal ganglia DA during chronic immune activation, in the present study, rhesus monkeys chronically exposed to recombinant human (rHu)-IFN-α (20 MIU/m2) were used to investigate whether prolonged cytokine exposure decreases DA release in the striatum using in vivo microdialysis and [11C]raclopride PET neuroimaging of the DA2 receptor (D2R) before and after amphetamine (AMPH) administration. To also determine whether changes in extracellular DA release might be influenced by changes in the DA transporter (DAT), DAT binding was assessed during IFN-α compared with saline administration using the DAT ligand [18F]2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-chlorophenyl)-8-(2-fluoroethyl)nortropane (FECNT; Goodman et al, 2000).

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Animals

Four male (11–15 kg) and four female (4–8 kg) rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), aged 8–12 years, were housed either individually in adjacent cages (n=7) or with a partner (n=1) in same-sex colony rooms. Animals were fed Purina monkey chow twice daily supplemented with fresh fruits and vegetables and maintained on a 0700–1900 light–dark cycle. All study procedures were a priori approved by the Emory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Design

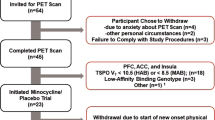

Animals were run in opposite sex pairs (to minimize disruption to the same-sex colony rooms), and treatment conditions were reversed after 3 months so that each animal received both saline and IFN-α (within subject design). Before treatment initiation, animals were habituated to study procedures in order to minimize stress reactivity. IFN-α (rHu-IFN-α-2b (Schering-Plough, Kenilworth, NJ)) 20 MIU/m2 or saline was administered subcutaneously in equivalent volumes (0.5–1.5 ml) between 0700 hours and 1000 hours, 5 days per week for 4 weeks (Felger et al, 2007), similar to the treatment schedule of patients receiving IFN-α monotherapy for malignant melanoma (Musselman et al, 2001). [18F]FECNT neuroimaging included all eight animals and occurred at the end of week 3. [11C]raclopride neuroimaging included four animals (one male and three females) and occurred during week 4, and in vivo microdialysis sampling included four animals (two males and two females) and occurred during weeks 2 and 4 of IFN-α and saline administration. For monkeys that underwent both in vivo microdialysis sampling and [11C]raclopride imaging during week 4 of treatment, in vivo microdialysis occurred before [11C]raclopride neuroimaging with at least 2 days separation. Figure 1 illustrates the order of in vivo microdialysis, PET neuroimaging, home cage behavioral assessments, and sucrose consumption testing. Home cage behavior was recorded in all animals on 3 days of each treatment week, and sucrose consumption was assessed over 2 days of weeks 2 and 4 of IFN-α or saline administration as described below. As a counterbalanced design was not employed in this study, additional in vivo microdialysis studies were conducted in two animals to demonstrate that there were no effects of repeated sampling (see Supplementary Figure S6 and Supplementary Table S1 for list of subject/procedure participation).

Timeline of study procedures. The order of in vivo microdialysis, PET neuroimaging, home cage behavioral assessments, and sucrose consumption testing procedures during 4 weeks of saline and IFN-α administration. Treatment conditions were reversed after 3 months so that each animal received both saline and IFN-α. Not all subjects underwent every study procedure; please see Supplementary Table S1 for a list of procedures/study participants.

In Vivo Microdialysis

Subjects were surgically prepared with guide cannulae implanted bilaterally above the caudate nucleus as described previously (Sawyer et al, 2012). Cannula placement was verified for each animal by MRI. Awake subjects underwent reverse in vivo microdialysis sessions with 100 mM high potassium (K+) followed by 250 μM AMPH (Gerhardt et al, 2002) for 10 min and 60 min sample collection each (Supplementary Figure S2), to determine effects of treatment on both voltage-dependent and transporter-mediated DA release. DA levels were determined as nanomolar concentrations in dialysate unadjusted for probe recovery. The DA responses to high K+ and AMPH were calculated as percent of baseline (extracellular DA concentration/mean of five baseline samples × 100). Samples were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography and electrochemical detection (Pehrson et al, 2012; see Supplementary Figure S6 for details).

PET Neuroimaging

Subjects were anesthetized and imaged using [11C]raclopride and [18F]FECNT to determine the binding potential (BPND) to D2R and DAT, respectively, on separate occasions. To measure DA release by displacement of [11C]raclopride, an AMPH challenge protocol was employed (0.5 mg/kg, i.v.) that involved baseline followed by post-AMPH scans (Supplementary Figure S3). BPND was calculated using the simplified reference tissue model with the cerebellum as a reference compartment for striatal regions of interest (Lammertsma and Hume, 1996; see Supplementary Figure S6 for details).

Behavior

Sucrose consumption was measured using a puzzle feeder (Supplementary Figure S4) requiring the monkeys to work to receive up to six 5-g sucrose pellets (Purina Test Diet, Richmond, IN) as reward. To control for potential anorexia or alterations in primary motivation for treats, on a separate day, six sucrose pellets were presented to monkeys in their regular feeders. Automated locomotor activity was recorded continuously over the duration of each treatment period using triaxial Actical accelerometers (MiniMitter, Bend, OR). Home cage behavior was also recorded for 3 sessions per week of saline or IFN-α administration and scored by trained observers blinded to treatment condition for the presence of depressive-like huddling behavior (Kalin, 1985; see Supplementary Figure S6 for testing details).

Statistics

For in vivo microdialysis, two-way repeated measures (RM) analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess DA responses before, during, and after high K+ and AMPH at week 2 vs week 4 separately in each treatment condition (saline or IFN-α). Because no differences were found between weeks 2 and 4 during saline treatment (see Supplementary Figure S6), responses to high K+ and AMPH from these weeks were averaged (across weeks 2 and 4) and compared with responses during weeks 2 and 4 of IFN-α treatment using two-way RM ANOVA. Sphericity was computed using Mauchly’s W and if sphericity was violated (Epsilon <0.75), the more conservative Greenhouse–Geisser correction was employed to adjust the degrees of freedom, thus preventing inflation of the F-ratio and reducing the type I error rate. For neuroimaging results, treatment (saline vs IFN-α) by region (caudate and putamen) effects were examined for [18F]FECNT BPND, baseline [11C]raclopride BPND, and Δ[11C]raclopride BP using RM ANOVA. Δ[11C]raclopride BP in the ventral striatum (including nucleus accumbens) was also compared between groups using a paired sample t-test. Behavior was examined for differences between IFN-α and saline and over time (week of treatment) using two-way RM ANOVA. Means and SDs were used to calculate effect size r from Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988). To examine the relationship between DA release and sucrose consumption, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was employed. All tests of significance were two-tailed with an α level of 0.05, and all post-hoc analyses were conducted using the Student–Newman–Keuls test of significance. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY) and SigmaStat (Systat, Jan Jose, CA) software packages.

RESULTS

In vivo Microdialysis

Surgical procedures resulted in successful placement of guide cannulae in all four animals so that 24 mm custom probes could be placed in the ventromedial region of the head of caudate nucleus (Supplementary Figure S1). As noted above, repeat in vivo microdialysis sampling before, during, and after high K+ and AMPH stimulation indicated no significant difference in the DA response between weeks 2 and 4 during saline administration (F[1.69,4.77]=1.25, p=0.348, Supplementary Figure S5A). Nevertheless, during IFN-α administration, there was a significant decrease in the DA response during week 4 compared with week 2 (F[1.32,3.95]=12.038, p<0.05, Supplementary Figure S5B). When the DA response during saline was compared with that during IFN-α treatment at weeks 2 and 4, a significant effect of treatment (F[2,6]=7.40, p<0.05) and treatment by time interaction was observed (F[1.95,5.85]=7.30, p<0.05), with post-hoc testing revealing a significant increase in the DA response at week 2 and a significant decrease in response at week 4 of IFN-α administration to both high K+ and AMPH compared with saline (p<0.05; Figure 2). Of note, the decrease in peak DA responses to high K+ and AMPH at 4 weeks IFN-α administration compared with saline corresponded to a 58 and 68% reduction with effect sizes of 0.60 and 0.58, respectively.

Stimulated dopamine (DA) release is reduced after 4 weeks interferon (IFN)-α administration. Saline and IFN-α (20 MIU/m2 s.c.) was administered to four rhesus monkeys for 4 weeks separated by at least 3 months, and in vivo microdialysis sampling was conducted at weeks 2 and 4. High potassium (K+) (100 nM) and amphetamine (AMPH) (250 nM) stimulation by reverse in vivo microdialysis resulted in significant increases in extracellular DA, and the peak responses to both high K+ and AMPH were significantly increased at week 2 and decreased at week 4 of IFN-α administration compared to mean saline responses. Data are presented as mean±SEM. *p<0.05 compared with saline.

PET Neuroimaging

[11C]raclopride evaluation of D2R binding demonstrated marked uptake in the striatum (Supplementary Figure S7) of the four animals studied. The baseline (pre-AMPH) BPND was significantly decreased following 4 weeks of IFN-α administration compared with saline (main effect treatment: F[1,3]=23.924, p<0.05) (Figure 3) in both caudate and putamen (p<0.05). When calculating percent change in BPND (%ΔBP) from baseline, no differences in AMPH-induced [11C]raclopride displacement were found between groups during saline vs IFN-α treatment. Because calculating [11C]raclopride displacement using solely %ΔBP (%ΔBP=100 × (BPAMPH−BPBL)/BPBL) can mask group differences in the absolute (ΔBP=BPAMPH−BPBL) vs relative amount of amphetamine-induced [11C]raclopride displacement when marked differences in baseline [11C]raclopride BPND (BPBL) exist between groups (as observed here), we conducted an additional analysis of the displacement of [11C]raclopride using ΔBP (see Supplementary Figure S6 for further explanation and Supplementary Table S2 for raw data). Δ[11C]raclopride BP was significantly decreased during IFN-α administration at 4 weeks compared with saline (main effect of treatment: F[1,3]=357.717, p<0.001). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the effect of IFN-α on ΔBP was manifest in the putamen (p<0.05) but not in the caudate (Figure 4), indicating less [11C]raclopride displacement in the putamen during IFN-α administration. Effect sizes for the differences in baseline BPND and AMPH-induced Δ[11C]raclopride BP in the putamen between saline and 4 weeks IFN-α administration were 0.83 and 0.50, respectively. Of note, similar decreases in ΔBP between saline and IFN-α treatments were found in the ventral striatum (including nucleus accumbens; saline=0.88, SEM=0.08 vs IFN-α=0.77, SEM=0.09; t[4]=−3.849, p<0.05). [18F]FECNT uptake was observed in the striatum (Supplementary Figure S8) of all eight subjects, but the BPND did not significantly differ between IFN-α and saline for either the caudate or putamen (main effect of treatment: F[1,7]=0.106, p=0.754; Figure 5). No effect of sex on IFN-α effects on [18F]FECNT BP were found (see Supplementary Figure S6).

Differences in baseline [11C]raclopride binding potential (BPND) at 4 weeks interferon (IFN)-α administration compared to saline. Saline and IFN-α (20 MIU/m2 s.c.) were administered to four rhesus monkeys for 4 weeks separated by at least 3 months, and dopamine (DA)2 receptor (D2R) binding was assessed at week 4 using [11C]raclopride. Representative images of [11C]raclopride BPND in the striatum of one animal during saline (a) and IFN-α (b) administration. BPND was significantly decreased in both the caudate and putamen during IFN-α administration compared to saline in four animals (c). The color bar ranges from 0 to 6 with a threshold of 1. *p<0.05 compared with saline.

Differences in amphetamine (AMPH)-induced displacement of [11C]raclopride at 4 weeks interferon (IFN)-α administration compared to saline. Saline and IFN-α (20 MIU/m2 s.c.) were administered to four rhesus monkeys for 4 weeks separated by at least 3 months, and AMPH-induced displacement of [11C]raclopride from the dopamine (DA)2 receptor (D2R) was assessed at week 4. Representative phase-contrast images of the Δ[11C]raclopride binding potential (BP) (AMPH−baseline) in the striatum of one animal during saline (a) and IFN-α (b) administration. The Δ[11C]raclopride BP was significantly decreased in the putamen but not in the caudate during IFN-α administration compared with saline in four animals (c). The color bar ranges from 0 to −6 with a threshold of 1. *p<0.05 compared with saline.

No differences in [18F]FECNT binding potential (BPND) were observed at 4 weeks interferon (IFN)-α administration compared to saline. Saline and IFN-α (20 MIU/m2 s.c.) were administered to eight rhesus monkeys for 4 weeks separated by at least 3 months, and binding to the dopamine transporter (DAT) was assessed toward the end of week 3 using [18F]FECNT. Representative images of [18F]FECNT BPND in the striatum of one animal during saline (a) and IFN-α (b) administration. BPND was similar between saline and IFN-α conditions in both the caudate and putamen (c). The color bar ranges from 0 to 17 with a threshold of 1.

Behavior

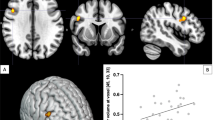

Sucrose consumption was measured under two conditions in all eight animals. Sucrose consumption from a puzzle feeder was significantly lower during IFN-α administration compared with saline (main effect of treatment F[1,7]=14.627, p<0.01), and a significant difference between weeks 2 and 4 of treatment was also observed (main effect of time F[1,7]=9.398, p<0.05). Post-hoc testing revealed a significant decrease in sucrose consumption from the puzzle feeder in IFN-α vs saline-treated animals at week 2 (p<0.05) and at week 4 (p<0.01), and a significant decrease in sucrose consumption from the puzzle feeder at week 4 vs week 2 of IFN-α administration (p<0.01; Figure 6a). There was no significant difference in sucrose consumption between saline and IFN-α administration, or between weeks 2 and 4 of treatment, from the regular feeder that did not require the animals to work to receive sucrose pellets (Figure 6b). Interestingly, the amount of sucrose pellets consumed from the puzzle feeder correlated with the DA response to high K+ during week 4 of IFN-α administration in the four animals that underwent in vivo microdialysis sampling (rs=1.0, p<0.01; Figure 6c). A similar relationship was observed between the amount of sucrose pellets consumed and the in vivo microdialysis response to AMPH, yet this did not reach statistical significance (rs=0.80, p=0.2). No correlations were found with the in vivo microdialysis response to high K+ or AMPH with sucrose consumption from the regular feeder at week 4, and no significant correlations were found between the in vivo microdialysis response to high K+ or AMPH and sucrose consumption from the puzzle or regular feeder at week 2. Moreover, no significant differences in huddling behavior or locomotor activity were found between treatment conditions. Finally, sex differences did not influence the impact of IFN-α on sucrose consumption from either the puzzle feeder or the regular feeder (see Supplementary Figure S6).

Decreased sucrose consumption from a puzzle feeder was observed at 2 and 4 weeks of interferon (IFN)-α administration and correlated with reduced dopamine (DA) release at week 4. Saline and IFN-α (20 MIU/m2 s.c.) was administered to eight rhesus monkeys for 4 weeks separated by at least 3 months, and sucrose consumption was tested at weeks 2 and 4. The percent of 5-g sucrose tablets consumed (out of six) from a puzzle feeder that required monkeys to work for reward was significantly reduced at weeks 2 and 4 of IFN-α vs saline administration (a). No treatment differences were observed when sucrose pellets were presented in the animals’ regular feeders as a control for anorexia and reduced appetitive behavior (b). Decreased sucrose consumption from the puzzle feeder was correlated with reduced DA responses to high potassium (K+), as measured by in vivo microdialysis, at week 4 of IFN-α administration (c). Data are summarized as mean±SE, *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

DISCUSSION

Herein we report significantly reduced stimulated DA release in the striatum of rhesus monkeys after 4 weeks of peripheral IFN-α administration. These findings were apparent across techniques (in vivo microdialysis and neuroimaging) and are consistent with previous neuroimaging studies in humans exposed to IFN-α and other peripheral inflammatory stimuli that have observed reduced neural responses in the ventral striatum to hedonic reward. Interestingly, reduced DA release was observed at 4 weeks of IFN-α administration, a time point when neurovegetative symptoms are prominent in IFN-α-treated humans (Capuron et al, 2002). Week 4 of IFN-α administration was also the time point when anhedonia-like behavior (reduced sucrose consumption from a puzzle feeder) was most apparent. Anhedonia is a behavior classically associated with DA release and reward (Wise, 2008). Reduced sucrose consumption, as measured by the puzzle feeder task, was also correlated with decreased striatal DA release in response to reverse in vivo microdialysis challenge with high K+. Therefore, the present findings substantiate the idea that peripheral inflammatory cytokines target basal ganglia DA function, leading to behavioral alterations.

The specific mechanisms by which cytokines affect DA function are currently unknown, but may involve decreases in DA synthesis, impaired packaging, and/or decreased DA receptor signaling. Although reduced DA release was observed at week 4, increased release in response to high K+ and AMPH was observed during week 2 of IFN-α administration. Interestingly, this early increase in DA release is consistent with literature in rodents whereby increased monoamines and metabolites have often been observed regionally following acute or sub-chronic exposure to peripheral immune challenge or inflammatory cytokines (Dunn, 2006; Felger and Miller, 2012; O’Connor et al, 2009). This early increase in DA release may be responsible for the decrease in D2R binding observed at week 4 and explain the unexpected association of decreased D2R with decreased DA release at this time point. Increased DA synthesis and release may downregulate D2Rs and decrease subsequent DA synthesis through end product inhibition (Carlsson et al, 1976). Of note, reduced striatal D2R binding has been reported in patients with depression (Moses-Kolko et al, 2012). Although it is unknown whether decreased D2R binding reflects a change in pre- or postsynaptic receptors, both types of receptors are thought to be important in regulation of DA synthesis (Anzalone et al, 2012). Furthermore, early increases in cytosolic DA and chronic inflammatory activity may interact to increase oxidative stress, which may impact DA synthesis and release over time.

Synthesis of DA and other monoamines is also dependent on the enzyme cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). BH4 is necessary for both conversion of phenylalanine (Phe) to tyrosine (Tyr), the primary amino-acid precursor of DA, and for Tyr conversion to L-DOPA. Interestingly, inflammatory cytokines have been shown to induce GTP-cyclohydrolase I, the enzyme necessary for BH4 synthesis, and can stimulate monoamine synthesis (Capuron et al, 2011), potentially contributing to early increases in DA metabolism and release. However, sustained inflammation can increase both reactive oxygen species and inducible nitric oxide synthase activity that may ultimately lead to decreased BH4 availability and thus reduced DA synthesis (Felger and Miller, 2012; Neurauter et al, 2008). Furthermore, there is some evidence that inflammatory cytokines and inflammation may negatively affect expression and function of the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (Felger and Miller, 2012; Kazumori et al, 2004). Normal vesicular sequestration and release is particularly important in DAergic cells due to the risk of auto-oxidation of DA and the formation of neurotoxic quinones and free radicals (Guillot and Miller, 2009). Therefore, an early increase in DA synthesis or release by cytokines, as observed during week 2 of IFN-α administration in the present study, could contribute to oxidative stress, leading to subsequent decreases in DA synthesis and impaired release. In fact, we have recently reported diminished conversion of Phe to Tyr in patients after 12 weeks of IFN-α therapy that was related to decreased DA and DA metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid and development of fatigue (Felger et al, 2013). Similar changes in Tyr metabolism and its association with behavioral changes have been reported in other models of chronic inflammation or medical illness (Capuron et al, 2011; Neurauter et al, 2008).

As mentioned above, numerous studies in rodents have examined whole brain or regional changes in neurotransmitter content following acute or sub-chronic cytokine treatment. The advantage of the present study was the ability to examine changes in stimulated DA release over time in the same animals during chronic cytokine administration. Although these techniques were not as sensitive to baseline synaptic DAergic tone, which could influence D2R binding, it did allow observation of changes in the magnitude of evoked DA release, which is relevant to behavior (Robinson et al, 2011). Indeed, DA released from burst-firing of DA neurons is associated with a number of neurobehavioral processes, including motivation and reward (Overton and Clark, 1997). Nevertheless, the microdialysis and PET neuroimaging techniques employed in this study do not provide information regarding specific mechanisms of cytokine effects on DA neurotransmission. Furthermore, whether changes in basal ganglia DA occur as the result of direct effects of cytokines on DA neurotransmission, or whether they are the result of upstream effects of other brain regions or neurotransmitter systems remains to be determined. For example, serotonin has known interactions with striatal DA and is thought to contribute to symptoms of cytokine-induced depression (Anisman and Merali, 2003; Bull et al, 2008; Lotrich et al, 2009; Raison et al, 2009).

One interesting behavioral finding of the current study was a progressive decrease in sucrose consumption from a puzzle feeder that correlated with decreased DA release at week 4 of IFN-α administration. However, after 2 weeks of IFN-α administration, a small but significant decrease in sucrose consumption was observed at a time when there was increased DA release. This finding suggests that the marked decreases in D2R that were observed at week 4 may be apparent much earlier during IFN-α treatment and may contribute to reduced DA signaling (and resultant behavioral changes) despite increased ligand. Future studies examining D2R early after IFN-α administration are therefore warranted.

Although sucrose consumption has been frequently used as a putative indicator of anhedonia-like behavior in laboratory animals (Papp et al, 1991), it is worth noting that, in addition to decreased motivation for reward, decreased sucrose consumption from the puzzle feeder could be related to impairments in attention or cognitive function, or psychomotor slowing. In fact, in addition to decreased ventral striatal responses to a hedonic reward task in IFN-α-treated humans (Capuron et al, 2012), we have observed psychomotor slowing, as measured by the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery, and increased anterior cingulate cortex activation to task-related error processing (Capuron et al, 2005; Majer et al, 2008). Psychomotor changes in IFN-α-treated patients correlated with fatigue, and may be related to changes in basal ganglia DA. Similarly, fronto-striatal dysfunction has also been observed in major depression, and includes alterations in functional connectivity between the ventral striatum and the anterior cingulate cortex (Furman et al, 2011).

Previously, we have demonstrated that rhesus monkeys administered IFN-α exhibited early and persistent increases in depressive-like huddling behavior in up to half of animals and changes in locomotor activity that were related to decreased DA metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid (Felger et al, 2007; Felger and Miller, 2012). Significant increases in huddling behavior or changes in locomotor activity were not observed in the current study. It should be noted, however, that in the present study the animals were singly housed in social colony rooms (due to conflict among social pairs and surgical implantation of guide cannulae), removing much of the social aspect of behavior and limiting the number of behaviors that we were able to score. Therefore, a lack of difference in huddling behavior between saline and IFN-α administration may be related to the current housing conditions, as huddling behavior can be influenced by social status and housing environment (Shively et al, 2005; Suomi and Harlow, 1972). The increased age of the animals may have also contributed to a lack of treatment effect on locomotor activity and huddling behavior.

There are several limitations of this study that should be addressed, the first being the small sample size, although 3–5 animals per treatment group are common in nonhuman primate studies, particularly those employing in vivo microdialysis and neuroimaging techniques (Czoty et al, 2000; Sawyer et al, 2012). Nevertheless, as with previous studies, a within subject design was used to reduce effects of inter-subject variability and increase statistical power (Felger et al, 2007; Felger and Miller, 2012). Although monkeys provide a useful model for repeat in vivo microdialysis sampling to measure neurotransmitter changes over time, sampling intervals were limited to every 2 weeks to preserve tissue integrity (Czoty et al, 2000), and therefore we could only capture IFN-α effects on DA neurotransmission at two time points throughout 4 weeks of treatments. An additional concern is that marked decreases in D2R binding were found in both the caudate and the putamen, yet a significant effect of IFN-α treatment on AMPH-induced DA release as assessed by PET neuroimaging was only seen in the putamen. Because decreased DA release in response to AMPH was observed in the caudate by in vivo microdialysis, the data suggest that in vivo microdialysis may be more sensitive in detecting the effect of IFN-α on AMPH-induced DA release than neuroimaging. Although the putamen is a more difficult structure to reliably target for in vivo microdialysis in monkeys, a greater effect of IFN-α on DA release may have been observed in this region, given the neuroimaging findings.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that chronic inflammatory cytokine exposure decreased striatal DA release and D2R binding without affecting binding to the DAT. These findings complement neuroimaging results from humans administered inflammatory cytokines or immune challenges indicating decreased basal ganglia DA function. Inflammatory cytokines may affect multiple aspects of DA neurotransmission, leading to decreased synthesis, impaired packaging, and decreased D2R signaling, all of which may interact to a greater or lesser extent to reduce DA function. Symptoms, such as fatigue and psychomotor slowing, that appear to be mediated by basal ganglia DA have been difficult to treat with conventional antidepressants and stimulant medications. Future studies are needed to identify the precise mechanisms of cytokine action on DA function in order to determine appropriate pharmacological treatment strategies for these and other neurovegetative symptoms in both medically healthy and medically ill individuals with increased inflammation.

FUNDING AND DISCLOSURE

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health to AHM (R01MH083746, K05MH069124, and T32MH020018), and JCF (F32MH093054), and grants from the US Public Health Service to LLH (DA10344, DA00517), as well as the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30AI050409) and the Yerkes National Primate Research Center (P51OD11132). Andrew H. Miller has served as a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Lundbeck Research USA, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Schering-Plough Research Institute, and Wyeth/Pfizer Inc. and has received research support from Centocor Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Schering-Plough Research Institute. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Anisman H, Merali Z (2003). Cytokines, stress and depressive illness: brain-immune interactions. Ann Med 35: 2–11.

Anzalone A, Lizardi-Ortiz JE, Ramos M, De Mei C, Hopf FW, Iaccarino C et al (2012). Dual control of dopamine synthesis and release by presynaptic and postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors. J Neurosci 32: 9023–9034.

Bora E, Harrison BJ, Davey CG, Yucel M, Pantelis C (2012). Meta-analysis of volumetric abnormalities in cortico-striatal-pallidal-thalamic circuits in major depressive disorder. Psychol Med 42: 671–681.

Brydon L, Harrison NA, Walker C, Steptoe A, Critchley HD (2008). Peripheral inflammation is associated with altered substantia nigra activity and psychomotor slowing in humans. Biol Psychiatry 63: 1022–1029.

Bull SJ, Huezo-Diaz P, Binder EB, Cubells JF, Ranjith G, Maddock C et al (2008). Functional polymorphisms in the interleukin-6 and serotonin transporter genes, and depression and fatigue induced by interferon-alpha and ribavirin treatment. Mol Psychiatry 14: 1095–1104.

Capuron L, Gumnick JF, Musselman DL, Lawson DH, Reemsnyder A, Nemeroff CB et al (2002). Neurobehavioral effects of interferon-alpha in cancer patients: phenomenology and paroxetine responsiveness of symptom dimensions. Neuropsychopharmacology 26: 643–652.

Capuron L, Pagnoni G, Demetrashvili M, Woolwine BJ, Nemeroff CB, Berns GS et al (2005). Anterior cingulate activation and error processing during interferon-alpha treatment. Biol Psychiatry 58: 190–196.

Capuron L, Schroecksnadel S, Feart C, Aubert A, Higueret D, Barberger-Gateau P et al (2011). Chronic low-grade inflammation in elderly persons is associated with altered tryptophan and tyrosine metabolism: role in neuropsychiatric symptoms. Biol Psychiatry 70: 175–182.

Capuron L, Pagnoni G, Demetrashvili MF, Lawson DH, Fornwalt FB, Woolwine B et al (2007). Basal ganglia hypermetabolism and symptoms of fatigue during interferon-alpha therapy. Neuropsychopharmacology 32: 2384–2392.

Capuron L, Pagnoni G, Drake DF, Woolwine BJ, Spivey JR, Crowe RJ et al (2012). Dopaminergic mechanisms of reduced basal ganglia responses to hedonic reward during interferon alfa administration. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69: 1044–1053.

Carlsson A, Kehr W, Lindqvist M (1976). The role of intraneuronal amine levels in the feedback control of dopamine, noradrenaline and 5-hydroxytryptamine synthesis in rat brain. J Neural Transm 39: 1–19.

Chaudhury D, Walsh JJ, Friedman AK, Juarez B, Ku SM, Koo JW et al (2013). Rapid regulation of depression-related behaviours by control of midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature 493: 532–536.

Cohen JD (1988) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences 2nd edn Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Czoty PW, Justice JB Jr., Howell LL (2000). Cocaine-induced changes in extracellular dopamine determined by microdialysis in awake squirrel monkeys. Psychopharmacology 148: 299–306.

Dunlop BW, Nemeroff CB (2007). The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 327–337.

Dunn AJ (2006). Effects of cytokines and infections on brain neurochemistry. Clin Neurosci Res 6: 52–68.

Eidelberg D, Moeller JR, Dhawan V, Spetsieris P, Takikawa S, Ishikawa T et al (1994). The metabolic topography of parkinsonism. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 14: 783–801.

Eisenberger NI, Berkman ET, Inagaki TK, Rameson LT, Mashal NM, Irwin MR (2010). Inflammation-induced anhedonia: endotoxin reduces ventral striatum responses to reward. Biol Psychiatry 68: 748–754.

Felger JC, Miller AH (2012). Cytokine effects on the basal ganglia and dopamine function: the subcortical source of inflammatory malaise. Front Neuroendocrinol 33: 315–327.

Felger JC, Li L, Marvar PJ, Woolwine BJ, Harrison DG, Raison CL et al (2013). Tyrosine metabolism during interferon-alpha administration: association with fatigue and CSF dopamine concentrations. Brain Behav Immun 31: 153–160.

Felger JC, Alagbe O, Hu F, Mook D, Freeman AA, Sanchez MM et al (2007). Effects of interferon-alpha on rhesus monkeys: a nonhuman primate model of cytokine-induced depression. Biol Psychiatry 62: 1324–1333.

Furman DJ, Hamilton JP, Gotlib IH (2011). Frontostriatal functional connectivity in major depressive disorder. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord 1: 11.

Gerhardt GA, Cass WA, Yi A, Zhang Z, Gash DM (2002). Changes in somatodendritic but not terminal dopamine regulation in aged rhesus monkeys. J Neurochem 80: 168–177.

Goodman MM, Kilts CD, Keil R, Shi B, Martarello L, Xing D et al (2000). 18F-labeled FECNT: a selective radioligand for PET imaging of brain dopamine transporters. Nucl Med Biol 27: 1–12.

Guillot TS, Miller GW (2009). Protective actions of the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) in monoaminergic neurons. Mol Neurobiol 39: 149–170.

Kalin NH (1985). Behavioral effects of ovine corticotropin-releasing factor administered to rhesus monkeys. Fed Proc 44: 249–253.

Kazumori H, Ishihara S, Rumi MA, Ortega-Cava CF, Kadowaki Y, Kinoshita Y (2004). Transforming growth factor-alpha directly augments histidine decarboxylase and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 production in rat enterochromaffin-like cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 286: G508–G514.

Lammertsma AA, Hume SP (1996). Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage 4: 153–158.

Lotrich FE, Ferrell RE, Rabinovitz M, Pollock BG (2009). Risk for depression during interferon-alpha treatment is affected by the serotonin transporter polymorphism. Biol Psychiatry 65: 344–348.

Majer M, Welberg LA, Capuron L, Pagnoni G, Raison CL, Miller AH (2008). IFN-alpha-induced motor slowing is associated with increased depression and fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Brain Behav Immun 22: 870–880.

Moses-Kolko EL, Price JC, Wisner KL, Hanusa BH, Meltzer CC, Berga SL et al (2012). Postpartum and depression status are associated with lower [(11)C]raclopride BP(ND) in reproductive-age women. Neuropsychopharmacology 37: 1422–1432.

Musselman DL, Lawson DH, Gumnick JF, Manatunga AK, Penna S, Goodkin RS et al (2001). Paroxetine for the prevention of depression induced by high-dose interferon alfa. N Engl J Med 344: 961–966.

Neurauter G, Schrocksnadel K, Scholl-Burgi S, Sperner-Unterweger B, Schubert C, Ledochowski M et al (2008). Chronic immune stimulation correlates with reduced phenylalanine turnover. Curr Drug Metab 9: 622–627.

O’Connor JC, Lawson MA, Andre C, Moreau M, Lestage J, Castanon N et al (2009). Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activation in mice. Mol Psychiatry 14: 511–522.

Overton PG, Clark D (1997). Burst firing in midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 25: 312–334.

Papp M, Willner P, Muscat R (1991). An animal model of anhedonia: attenuation of sucrose consumption and place preference conditioning by chronic unpredictable mild stress. Psychopharmacology 104: 255–259.

Pehrson AL, Cremers T, Betry C, van der Hart MG, Jorgensen L, Madsen M et al (2012). Lu AA21004, a novel multimodal antidepressant, produces regionally selective increases of multiple neurotransmitters-A rat microdialysis and electrophysiology study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 23: 133–145.

Raison CL, Borisov AS, Majer M, Drake DF, Pagnoni G, Woolwine BJ et al (2009). Activation of central nervous system inflammatory pathways by interferon-alpha: relationship to monoamines and depression. Biol Psychiatry 65: 296–303.

Robinson DL, Zitzman DL, Williams SK (2011). Mesolimbic dopamine transients in motivated behaviors: focus on maternal behavior. Front Psychiatry 2: 23.

Savitz J, Frank MB, Victor T, Bebak M, Marino JH, Bellgowan PS et al (2013). Inflammation and neurological disease-related genes are differentially expressed in depressed patients with mood disorders and correlate with morphometric and functional imaging abnormalities. Brain Behav Immun 31: 161–171.

Sawyer EK, Mun J, Nye JA, Kimmel HL, Voll RJ, Stehouwer JS et al (2012). Neurobiological changes mediating the effects of chronic fluoxetine on cocaine use. Neuropsychopharmacology 37: 1816–1824.

Shively CA, Register TC, Friedman DP, Morgan TM, Thompson J, Lanier T (2005). Social stress-associated depression in adult female cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Biol Psychol 69: 67–84.

Suomi SJ, Harlow HF (1972). Depressive behavior in young monkeys subjected to vertical chamber confinement. J Comp Physiol Psychol 80: 11–18.

Tye KM, Mirzabekov JJ, Warden MR, Ferenczi EA, Tsai HC, Finkelstein J et al (2013). Dopamine neurons modulate neural encoding and expression of depression-related behaviour. Nature 493: 537–541.

Wichmann T, DeLong MR (2003). Functional neuroanatomy of the basal ganglia in Parkinson’s disease. Adv Neurol 91: 9–18.

Wise RA (2008). Dopamine and reward: the anhedonia hypothesis 30 years on. Neurotox Res 14: 169–183.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Ruth Connelly, Juliet Brown, Paul Chen, and the Emory Division of Animal Resources for expert technical assistance, and Marieke van der Hart at brainsonline.com for excellence in HPLC sample analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Felger, J., Mun, J., Kimmel, H. et al. Chronic Interferon-α Decreases Dopamine 2 Receptor Binding and Striatal Dopamine Release in Association with Anhedonia-Like Behavior in Nonhuman Primates. Neuropsychopharmacol 38, 2179–2187 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.115

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.115

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Inflammatory biotype of ADHD is linked to chronic stress: a data-driven analysis of the inflammatory proteome

Translational Psychiatry (2024)

-

New and emerging approaches to treat psychiatric disorders

Nature Medicine (2023)

-

Biological factors influencing depression in later life: role of aging processes and treatment implications

Translational Psychiatry (2023)

-

PET imaging of animal models with depressive-like phenotypes

European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (2023)

-

Functional connectivity in reward circuitry and symptoms of anhedonia as therapeutic targets in depression with high inflammation: evidence from a dopamine challenge study

Molecular Psychiatry (2022)