Abstract

The tendency for some individuals to partake in high-risk behaviors (eg, substance abuse, gambling, risky sexual activities) is a matter of great public health concern, yet the characteristics and neural bases of this vulnerability are largely unknown. Recent work shows that this susceptibility can be partially predicted by laboratory measures of reward seeking under risk, including the Balloon Analog Risk Task. Rats were trained to respond on two levers: one of which (the ‘add lever’) increased the size of a potential food reward and a second (the ‘cash-out lever’) that led to delivery of accrued reward. Crucially, each add-lever response was also associated with a risk that the trial would fail and no reward would be delivered. The relative probabilities that each add-lever press would lead to an addition food pellet or to trial failure (risk) were orthogonally varied. Rats exhibited a pattern of responding characteristic of incentive motivation and risk aversion, with a subset of rats showing traits of high-risk taking and/or suboptimal responding. Neural inactivation studies suggest that the orbitofrontal cortex supports greater reward seeking in the presence or absence of risk, whereas the medial prefrontal cortex is required for optimization of patterns of responding. These findings provide new information about the neural circuitry of decision making under risk and reveal new insights into the biological determinants of risk-taking behaviors that may be useful in developing biomarkers of vulnerability.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Adolescents and young adults are prone to engaging in a range of high-risk behaviors associated with life-long health-related complications, including substance abuse and risky sexual behaviors. Moreover, certain individuals are intrinsically more likely to exhibit high-risk behaviors and thus to suffer the consequences of them. Despite the public health significance of understanding the behavioral and biological markers of this vulnerability, we know remarkably little about its determinants or underlying mechanisms.

In human beings, dimensions of temperament linked to high-risk behaviors are usually measured with self-report questionnaires. These instruments have been used to discriminate between subjects that vary according to traits such as impulsivity, novelty seeking and sensation seeking and reward sensitivity (Zuckerman et al, 1978; Patton et al, 1995; Weber et al, 2002; Acton, 2003; Llewellyn, 2008). That being said, although self-report measures may be useful in stratifying subjects, they are limited as tools for use in experimental studies aimed at further interrogating the neurobiology of high-risk behaviors. Progress in this area has been facilitated by the development of behavioral measures of risk-related decision making, including the Balloon Analog Risk Task (BART) (Lejuez et al, 2002, 2003; Hunt et al, 2005; White et al, 2008). In this procedure, subjects make a decision about the amount of risk they are willing to accept to obtain a reward on a given trial. They press one button successively to increase the amount of earned monetary reward, but because each press is also associated with a chance of trial failure (with concomitant loss of reward earned during that trial), subjects must balance their desire for larger gains with their desire to avoid risk of reward forfeiture. For any given trial, subjects can either continue accepting risk until failing or they can end the trial by accepting the money earned up to that point by pressing an alternative button. In general, a relatively higher number of responses per trial is thought to indicate greater willingness to accept risk and is reported to positively correlate to a significant, albeit limited, degree with ‘real-world’ aspects of risk-taking and/or sensation-seeking behavior (Lejuez et al, 2002, 2003; Aklin et al, 2005; Hunt et al, 2005; Bornovalova et al, 2009; Crowley et al, 2009). That being said, it is possible that dimensions of behavior measured by the BART are sensitive to some, but not all, forms of impulsivity; a recent study suggests that relatively higher risk acceptance is present in bipolar patients with co-morbid alcohol use problems, but not those without an alcohol use disorder (Kathleen Holmes et al, 2009).

For these reasons, behavioral measures such as the BART can be used to explore the systems and cellular processes involved in making decisions about risk. In a recent functional imaging study, accepting risk was associated with changes in the blood oxygenation levels within a network that includes the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, insula, striatum, and ventral midbrain (Rao et al, 2008). Moreover, increases in activity within the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, particularly in the right hemisphere, were specifically linked with the decision-making processes that lead to acceptance of greater risk (Rao et al, 2008), suggesting that this brain structure mediates the evaluative functions required for optimal behavioral control in the task. Owing to the limitations associated with functional neuroimaging experiments, the causal contributions of these brain regions to decision making remain unknown.

To further delineate the biological origins of decision making under risk, we developed an instrumental procedure for use in rats that captures key aspects of the BART. In this manuscript, we describe initial efforts to provide validation for the animal measure that spans both behavioral and neural levels of analysis. First, we investigated behavioral sensitivity to variation in risk and reinforcement probability functions to determine whether responding was being determined by these factors. These efforts involved the novel performance metrics (eg, measures of within subject, within session variability of responding) and task conditions (eg, risk-free probe trials that allow for free-choice behavior during risk sessions). As a good deal of work in the BART revolves around the predictive value of individual differences in performance, we next set out to describe between subject variation in task performance that may be subjected to neural and genetic analyses. Third, we tested the function for two frontal regions implicated in human fMRI studies (Rao et al, 2008) to link theories of neural systems function during decision making under risk to systems recruited by rats to perform the task. We argue that the integrated neural and behavioral validation of the task supports the usefulness of this rodent measure of risk-related decision making.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Adult male Long-Evans rats (Harlan, Indianapolis IN) were used in this study. The subjects were ∼225–300 g in body weight at the inception of testing. An initial food restriction scheme was used to reduce baseline body weights to ∼85%; in addition to the food rewards obtained during testing, the rats were supplied with a portion of standard laboratory rat chow (Purina) in their home cage, ∼1 h post-testing.

Behavioral Training and Testing

Training and testing was conducted in chambers fitted with a house light, internal stimulus lights, food-delivery magazine, and two retractable lever positioned to the left and right of the magazine (Med-Associates, St Albans VT). The boxes were controlled by a PC running Med-PC IV (Med-Associates).

Subjects were first trained to respond on both levers in two separate sessions using a fixed ratio (FR)-1 schedule of reinforcement for 45-mg dustless precision, purified diet pellets (Bio-Serv; Frenchtown NJ). Subsequently, they were trained on an FR-3 and then FR-10 on the designated ‘add’-lever; subjects were progressed during this initial stage of training when they obtained at least 30 outcomes in a session. They were then familiarized with the general design of the task in a 50-trial ‘forced’ task in which only the add lever was presented until the rats responded between 2 and 15 times (randomly chosen from trial to trial); the add lever was then withdrawn and the cash-out lever was presented. A single cash-out response dispensed a number of pellets equal to the number of add-lever presses permitted on that trial.

The rats then began daily testing on risk and no-risk variants of the actual task (all 50 trials long) with both levers present. At this stage, all animals were trained and moved forward as a group; no individualized criteria were used to govern the progression of training. During routine tests, the risk condition was signaled by illuminating the house light from the onset of testing; the no-risk conditions was signaled by illumination of an internal stimulus light that was somewhat distinct from the house light; these lights remained on at all times during the session, except during time-outs. In the risk version, the rat could respond on the add lever until (1) it caused trial failure and reward forfeiture by responding more than permitted by the risk schedule on that trial (resulting in both levers being retracted and a 5-s time-out (signaled by lights off) being enforced) or (2) it pressed the cash-out lever to trigger delivery of earned reinforcement. In the no-risk version, the principal difference was that the rat could respond up to 100 times on the add lever before cashing out, which was, functionally, a no-risk version of the task as no rat ever made more than 25 presses before cashing out.

Initially, the rats were trained ∼6 days a week with half their sessions being risk and half being no-risk versions (the order was pseudorandom and not alternating); the risk was set at 11.1% chance of trial failure per add-lever press. After 1–2 weeks of training, a 16.7% risk condition was also occasionally presented. (These risk value were related to the maximum number of presses that would be required to fail every single trial. With the first press in every trial being ‘safe’ and the maximum number of presses set to 7 or 10, the resulting probabilities were 16.7 or 11.1%, respectively.) In addition, the probability of gaining additional reinforcement per add-lever press was initially 100%, but was quickly decreased over training days to 50 or 33%. The measures collected in each daily session were number of add responses made per trial (for both successful and failed trials), total number of pellets earned, number of failed trials, and session duration. Using these metrics, we were able to calculate the mean number of add-lever presses across the 50 trials, as well as the variance of these 50 values for each animal. As variance increases as a function of the mean, the variance measure was expressed as the ratio of the variance/mean. In a subset of rats, we also collected latency data, including latency to make the first add-lever press once the levers are presented, and the latency to retrieve the pellet once it was dispensed.

As the cash-out value (either the raw value or the value adjusted by eliminating failed trials) is negatively skewed (meaning that it is biased by the trials in which subjects are the most risk averse), we sought to measure free-choice behavior during performance by intermixing probe trials (ie, trials during which the animal could respond as much as it chose) with the standard 50 risk trials. This was performed in a subset of rats because the program modifications required to present these trials was introduced after some cohorts had completed testing. After completing 10 standard trials, probe trials were presented approximately every 4–6 trials. Of course, these probes might be seen altering the perceived risk of the session; however, because they were presented equivalently often irrespective of the amount of risk on standard trials, any parametric effects of session risk on free choice in probe trials must be driven by perceptions of relative differences in risk across these sessions. These unsignaled probe trials that occurred in the context of risk (being surrounded by standard trials) permitted a clean assessment of free-choice responding during risk sessions, as compared with standard trials in which the risk function artificially truncated the behavior.

For the behavioral studies described here, data were collected after 2–3 weeks of training. For the infusion studies, animals had about 6 weeks of training before surgery. Essentially, the rats used in the infusion studies contributed their baseline data to the overall behavioral analysis and then underwent surgery (see below) before an additional 3–6 weeks of retraining conducted to confirm that responding, after surgery, was stable (subjects completed all their trials and exhibited mean cash-out values that did not vary by >20% when similar test conditions were imposed).

During the behavioral and infusion studies, certain task parameters (eg, risk of trial failure, reinforcement probability) were varied to make the ascertainments described here. Task parameters were always varied within subjects in a counter-balanced, cyclic Latin Square design across the subjects to control for task order effects.

Surgeries

Rats were first anesthetized with isoflurane (3–5% in an induction box followed by 2–4% by a nose cone) and then placed in a stereotaxic apparatus. Briefly, holes were drilled in the skull surface and 26-gauge stainless-steel guide cannulae (Plastics one, Roanoke, VA) targeting the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (n=14) or the ventrolateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) (n=15) were inserted bilaterally (mPFC: AP, +3.2, ML, ±0.5, DV, −2.0, relative to bregma; OFC: AP, +3.7, ML, ±3.0, DV, −3.0, relative to bregma, cannulae angled 14° toward midline). Three steel screws and dental acrylic affixed the guide cannulae to the skull. Stainless-steel obturators were maintained in the cannulae at all times, except during infusions. Rats were given the analgesic carprofen (5 mg/kg, subcutaneously.; Rimadyl, Pfizer) immediately before and for 2 days after the surgery. In addition, an antibiotic (sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim, 200 mg/40 mg per 5 ml; Hi-tech Pharmacal, Amityville NY) was added to the drinking water (0.5 mg/ml) for 2 weeks after surgery.

Microinfusion Procedures

Transient inactivation of the regions of interest was performed by bilaterally infusing a solution of the GABAA antagonist muscimol (0.03 nmol; Sigma-Aldrich) and the GABAB antagonist baclofen hydrochloride (0.3 nmol; Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (0.9%). On infusion days, the dummy cannulae were replaced with 33-gauge injection needles, extending 3.5 and 2 mm below the guide cannulae for mPFC and OFC, respectively; 0.5 μl of the muscimol and baclofen cocktail (MUS+BAC), or of vehicle, was administered at a rate of 0.2 μl/min using a microsyringe pump, and injection needles were left in place for 2 min to allow drug diffusion. Rats were freely–moving, whereas drug was being infused. Behavioral testing commenced 10 min after the infusion was completed.

After completion of the study, rats were anesthetized using isoflurane, and a 4% solution of trypan blue was infused using the same procedure described for drug infusions. Rats were then transcardially perfused with 10% formaldehyde. The brains were removed, cut on a cryostat at 60 μm thickness and counter-stained with Cresyl Violet to facilitate localization of the infusion.

Statistical Analyses

All comparisons and analyses were performed using SPSS (v15) running on a PC. All within subject contrasts were examined with ANOVA and/or two-tailed paired t-tests. Regressions involved stepwise or simple linear analyses, where appropriate.

RESULTS

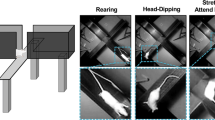

Rats were trained and tested in a task (Figure 1) that mirrors critical performance aspects of the BART task used in human beings. Across sessions, the probabilities that each add-lever press resulted in an increase in reward cache size or to trial failure were orthogonally varied between sessions and were never altered within a single session.

Trial schematic for the decision making under risk task. At trial onset, rats have an opportunity to accept risk to seek larger rewards by responding on an ‘add’ lever or to avoid risk and get access to that reward already earned by responding on a ‘cash-out’ lever. On a subset of trials, accepting risk would lead to trial failure and loss of reward. The probabilities that each add-lever press would lead to a larger reward cache or that it would lead to trial failure were independently manipulated. Each session was comprised of 50 trials, with an inter-trial interval of 3 s.

Risk Sensitivity

We first examined whether responding was independently sensitive to the levels of risk and the reinforcement rate imposed in the task. A group of modestly trained rats (∼2–4 weeks of daily training on risk and no-risk contingencies; n=81) were tested in sessions in which risk and reinforcement probability were independently varied in a within subjects design. In the 0% risk conditions, no trials ended in failure, but as risk increased from 11.1 to 16.7%, the number of failed trials increased dramatically (Table 1; main effect of risk: F(1,80)=129.6, p<0.0001). The effect of reinforcement probability reached the trend level (F(1,80)=3.4, p=0.07) and did not interact with risk (F(1,80)=0.8, p=0.3).

Regarding the average number of add-lever presses made per trial (Figure 2a), ANOVA revealed significant main effects of risk (F(2,87)=64.6, p<0.0001) and reinforcement probability (F(1,80)=20.3, p<0.0001), along with a significant interaction between these two factors (F(2,153)=4.3, p=0.02). These effects were mediated by the fact that increasing risk dramatically decreased mean add-lever responses made per trial, and lower probabilities of reinforcer accrual were associated with higher responding per trial. Moreover, the increase in responding associated with reduced probability of reward accrual was greater when risk was low, meaning that rats dynamically increased reward-seeking behavior to a larger degree when it was associated with no chance of reward loss. Though four separate cohorts of rats were tested to generate the dataset reported above (n=81 subjects), this large sample size was not required to statistically justify these conclusions, as these relationships were observable and significant in each of the three cohorts that were independently powered to find such an effect (ie the three of the four cohorts that made up n=24 subjects each).

Risk sensitivity of performance. (a) Whether reinforcement probability was 100 or 50% per add-lever press, increasing risk led to decreased average responses per trial. (b) Free-choice behavior in probe trials intermixed with standard trials during performance showed that rats voluntarily chose to respond less when they perceived the task to be more risky. A, B, and C: these letters indicate that all three risk conditions differed significantly from one another, irrespective of reinforcement probability at the p<0.005 level. *Significant difference between the 11.1 and 16.7% conditions: p<0.05.

A decrease in the average number of add-lever responses made per trial under increasing risk conditions could be accounted for solely by the increase of failures on trials that would have contributed higher response values, truncating the resulting distribution. To address this, we tested a subset of rats under conditions wherein up to 10 probe trials were intermixed with 50 standard risk trials in a pseudorandom manner (roughly every 4–6 trials); during probe trials, rats were able to respond as many times as they chose before cashing out. This analysis provided a direct measure of the rats’ voluntary responding in the session. Risk and reinforcement probability were again varied. Under these conditions, ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of risk (F(1,21)=3.7, p=0.02), with no main effect of reinforcement probability or risk × reinforcement probability interaction (both Fs<0.6). Figure 2b shows that, under the 50% reinforcement condition, rats voluntarily responded less, meaning that their behavior was risk sensitive in the expected manner.

Sensitivity to Variations in Reinforcement Probability

A recent study (Bornovalova et al, 2009) indicates that risk aversion increases as the payoff per inflation increases, leading to the hypothesis that subjects may target a desired prospect and accept only the amount of risk necessary to achieve that prospect. Consonant with this hypothesis, decreasing the probability that each add-lever press led to an additional pellet being earned (100 vs 50 vs 33%) significantly increased the mean number of presses made per cash-out trial (Figure 3b; main effect of reinforcement probability: F(2,160)=5.6, p<0.005; post hoc comparisons by two-tailed paired t-tests: 100 vs 50%: p=0.04; 100 vs 33%: p=0.002). That being said, most subjects were still observably risk averse under partial reinforcement conditions, making fewer than the optimal number of responses per trial (50%: 2.9±0.1; 33%: 3.0±0.1) and earning a total reward allocation below that which they were able to eat. This indicates that their risk aversion was not solely because of the fact that they could earn enough pellets to become sated, even when avoiding risk.

Behavioral characteristics of performance showing sensitivity to reinforcement probability and risk. (a) The theoretical relationship between the mean responses per trial and the overall size of the reward cache earned is an inverted U, with maxima at ∼5 responses per trial when there was an 11.1% risk of trial failure per add-lever press. Actual data obtained from a large group of rats mostly deviated from the theoretical optimal, with rats exhibiting relatively risk-averse behavior. (b) Decreasing the probability that each add-lever press increased reward cache size, increased responding, suggesting that rats increased reward-seeking responses when reward-delivery rate was lowered. (c) Under high-risk conditions (where the probability an add-lever press would lead to trial failure was 16.7%), the variability of responding was inversely related to reward magnitude earned, suggesting that high variance behavior was suboptimal in this task. *,***Significantly different at a p<0.05 or 0.001 level, respectively, vs control condition.

Optimization of Responding

The inverted-U function in Figure 3a shows the theoretical relationship predicted by an ideal observer between average number of responses per trial and total reward earned in a session, as well as actual data from 81 adult male rats. Subjects were tested under conditions in which (1) the first add-lever press was risk free, (2) each subsequent response was associated with an 11.1% risk of trial failure, and (3) each add-lever press earned an additional pellet. These data indicate that subjects were relatively risk averse (Figure 3b), producing an average of 2.8±0.1 responses per trial that was less than the total reward earned if they would have made ∼5 responses per trial. In this sense, rats are similar to human subjects in that they exhibit risk-averse profiles when performing the BART, producing fewer than the optimal number of responses (Bornovalova et al, 2009) and earning less reward than is possible probably because of over-estimation of the risk associated with the task.

Figure 3a also suggests that, relative to the ideal, a significant number of rats earn fewer pellets than they should; however, these curves anticipate that subjects produce the same number of responses on all trials in a session, in a sense optimizing their responding. In reality, subjects exhibit individual differences in the variability of their responding, and we hypothesized that high intra-subject, intra-session variance in the number of add-lever presses made across all 50 trials—reflecting combinations of both higher than optimal and lower than optimal trial completions—could be the cause of their inability to maximize reward receipt, particularly under high-risk conditions. To empirically examine this point, we calculated the variance of responses made per trial and divided it by the mean (to account for the fact that variance will naturally increase as the mean does). We compared performance (both mean and variance/mean of the responses per trial) for animals experiencing task conditions in which the chance of trial failure was 0% (a completely ‘safe’ control condition) or 16.7% (to impose considerable risk); the probability that an add-lever press would gain another pellet was held constant at 50%. Overall, both the mean and variance/mean measures were lower in the risk vs no-risk conditions (n=81; mean: t(80)=7.8, p<0.0001; variance/mean: t(80)=7.0, p<0.0001; two-tailed paired t-tests). The latter result suggests that subjects optimize or constrain performance as risk increases. Precisely as expected, stepwise regression shows that, when there was no risk of trial failure, the mean number of responses per trial was positively associated with pellets earned (adjusted r2=0.99, p<0.001; n=81; data not shown); in this case, the variability of responding was not significantly explanatory. However, in the condition in which there was a high degree of risk associated with each add-lever press, stepwise regression found that the variability of responding was negatively associated with pellets earned (Figure 3c; adjusted r2=0.15, p<0.001), with no variance being explained to a significant degree by the mean number of responses per trial. These data indicate that relatively high intra-subject, intra-session variability of responding could indicate relatively poor top-down control over behavior.

Incentive Processes

To test the idea that high mean and/or high variance responding may be primarily attributable to an incentive process (‘wanting’ of the pellets), we conducted an experiment in a set of rats that were tested as usual or after pre-feeding with reinforcer pellets. The probability that each add-lever press was reinforced was 100%, and the risk of trial failure was 11.1% per add-lever press. Pre-feeding significantly reduced the mean number of responses made per trial (Table 2; n=16; t(15)=2.3, p=0.03 by two-tailed paired t-test), but had no effect on the variability of responding (Table 2; t(15)=−1.3, p=0.22; two-tailed paired t-test). These data further support the notion that different psychological processes mediate these two dependent measures, with the average number of presses being related to an incentive process, while response variability is not.

Frontal Cortical Contributions

We next explored the function for distinct frontal cortical brain regions in aspects of risk-related responding, given recent results indicating that frontal regions contribute to a network of fore- and midbrain structures involved in decision making about risk and effective behavioral control during reward seeking (Rao et al, 2008). Rats (n=29) performed a version of the task in which reinforcement probability was fixed at 33% per add-lever press (to promote higher responding), but in which risk was varied across sessions (0 vs 11.1%); they were surgically cannulated, recovered, and then trained. Microinfusions of a GABA agonist cocktail (0.03 nmol of muscimol and 0.3 nmol of baclofen in 0.5 μl of vehicle; MUS+BAC) to transiently inactivate neural activity, or vehicle microinfusions, were made into either the mPFC—the functional analog of the human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Preuss, 1995; Brown and Bowman, 2002)—or into the OFC; the anatomical location of each infusion is shown in Figure 4a. When considering the mean number of responses per trial, omnibus ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between brain region (mPFC vs OFC) and infusion (vehicle vs MUS+BAC) (Figure 4b; F(1,27)=4.4, p=0.04; n=29); this interaction was due to the fact that inactivation of the OFC elicited a significant reduction in the mean number of presses per trial (Figure 4b; 11.1% risk: t(14)=3.5, p=0.003; 0% risk: t(14)=1.9, p=0.06 by two-tailed paired t-tests; n=15), whereas suppression of neural activity in the mPFC failed to affect this measure (11.1%: t(13)=−0.5, p=0.58; 0%: t(13)=0.0, p=0.98 by two-tailed paired t-tests; n=14). The opposite effect was found when examining the variability of responding after GABA agonist infusion into these brain regions (Figure 4c; brain region × infusion interaction: F(1,27)=8.4, p=0.007). Infusion of the GABA agonist cocktail into the mPFC increased the variance of responding (Figure 4c; 11.1%: t(13)=−3.2, p=0.006; 0%: t(13)=−1.6, p=0.11), which was unaffected after inactivation of the OFC (Figure 4c; 11.1%: t(14)=−1.1, p=0.25; 0%: t(14)=1.1, p=0.28). Neither infusion affected response latencies (data not shown).

Dissociable contributions of the mPFC and OFC on decision making under risk. (a) Infusion locations were centered on the ventral and lateral OFC or mPFC. (b) Inactivation of the OFC (top panel), but not of the mPFC (bottom panel) decreased the mean number of responses made per trial (mean±SEM), whereas (c) inactivation of the mPFC (bottom panel), but not of the OFC (top panel) increased response variability under risk conditions (mean ± SEM). (d) The variance of responding was negatively related to reward obtained when the mPFC was inactivated (bottom panel), while there was no correlation between these measures under vehicle infusion. *Significantly different at a p<0.05 level vs vehicle infusion; **p<0.005.

Importantly, the change in variability of responding elicited by mPFC inactivation produced a suboptimal response profile in that we measured a significant, negative relationship between the variance measure and reward obtained under mPFC inactivation (Figure 4d; adjusted r2=0.23, p=0.04 by simple linear regression), but not after vehicle infusion (Figure 4d; adjusted r2=0.06, p=0.69). (A negative relationship between baseline response variability and pellets earned, such as the one described above, is generally only observable under high-risk conditions). These data show a clear double dissociation between mPFC and OFC, as they relate to goal-directed decision making under risk and indicate that a neural circuit involving the mPFC is implicated in coordinating adaptive responding under risk in the rat, providing direct evidence that this structure participates in voluntary behavioral control in rats, as well as in human beings (Hare et al, 2009).

DISCUSSION

Considerable interest is focused on the neural mechanisms by which individuals make good and/or poor decisions about their behavior, particularly in circumstances in which there is a tension between the risks and rewards associated with their actions (Trepel et al, 2005; Floresco et al, 2008; Platt and Huettel, 2008). To date, most research in rodent models has focused on probabilistic or temporal discounting procedures in which subjects have to choose between certain/immediate/easy-to-obtain gratification and uncertain/delayed/hard-to-obtain reward (Winstanley et al, 2004; Walton et al, 2006; Bickel et al, 2007; Mar and Robbins, 2007; Wilhelm and Mitchell, 2008; St Onge and Floresco, 2009). Along with probabilistic discounting tasks, another set of procedures emphasize balancing the potential for reward gains and losses during choice behavior (van den Bos et al, 2006; Rivalan et al, 2009; Zeeb et al, 2009); these tasks probably more directly address phenotypes akin to ‘gambling’ behavior. Our efforts to develop a rodent analog of the BART represent an attempt to further develop cross-species assessments of risky decision making with translational potential.

Behavioral Characteristics

The results presented here point to a remarkable conservation of risk-averse-choice behavior, as well as an important component of incentive motivation in decision making, across species. The results presented here indicate clear risk sensitivity of performance; by using probe trials intermixed during standard risk sessions, we are able to directly measure the free-choice behavior of subjects during sessions in which they have developed a perception of risk. We also show that risk aversion increases as reward is accrued with less effort, indicating that goal-directed reward seeking is the basis for risk acceptance. Together, these data indicate that the choice behavior of rats during the BART task is consistent with descriptive accounts of human decision making under risk afforded by prospect theory (Tversky and Kahneman, 1981; Trepel et al, 2005).

Despite the fact that animals choose to respond more when risk is absent, they still make fewer responses than one would expect. It is important to note that animals experience zero-, low-, and high-risk sessions in an unpredictable manner. During any given no-risk session, they likely experienced risk in earlier daily tests, and it is expected that long-term reinforcement histories related to recent risk performance will carry over into the no-risk sessions. In addition, animals may not be willing to produce longer response chains during no-risk trials because doing so requires them to delay gratification.

A final note pertains to the fact that an important dimension of performance most closely related to suboptimal performance in this task is the intra-subject, intra-session variability of performance across the session, rather than simply the average number of responses made per trial. Most human and animal subjects are risk averse, meaning that they produce fewer responses per trial than the theoretical optimum. That being said, intra-subject, intra-session variability (mixing high and low cash-out values) reflects a behavioral style that actually confounds reward maximization. We propose that high intra-subject, intra-session variability of responding is likely to reflect a behavioral style in which instantaneous reinforcement histories overwhelmingly drive performance. In ‘gambling’ tasks, reward is maximized when subjects follow long-term reinforcement rules, as opposed to adapting behavior in response to real-time gains and losses because the outcome of any given trial is purely probabilistic. In that sense, we view high intra-subject, intra-session variability as a behavioral index of poor self-control over risk-taking behavior.

Frontal Cortical Mechanisms

This study provides direct evidence that the mPFC, arguably the rodent functional analog of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Preuss, 1995; Brown and Bowman, 2002), is involved in constraining and optimizing responding, in that subjects with temporary inactivation of this brain region exhibit a transient increase in the variability of responding that represents a suboptimal, maladaptive overall behavioral profile. These observations are consistent with recent work suggesting that mPFC inactivation in rats decreases risk aversion in a probabilistic-choice task (St Onge and Floresco, 2009) and implicating the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in self-control and reflective processes underlying decision making in human beings (Rao et al, 2008; Hare et al, 2009).

Alternatively, the OFC seems to be required for the full expression of incentive motivation to obtain large value rewards, in that its inactivation transiently decreases the average number of responses made per trial. Although a broader network of structures likely contributes to the multiple components of decision making under risk (Dalley et al, 2008; Floresco et al, 2008; Rao et al, 2008), these results describe a clear double dissociation within the frontal lobe in how medial and orbital regions contribute to cognitive and motivational aspects of decision making.

The mPFC and OFC probably exert their influence on performance in our task through direct regulation of specific striatal zones. The mPFC innervates ventromedial aspects of the striatum, including the nucleus accumbens (Berendse et al, 1992; Sesack and Pickel, 1992), whereas the specific subdivision of the OFC targeted here innervates ventrolateral portions of the striatum, including the putamen (Schilman et al, 2008). Notably, prefrontal cortical fibers interact with inputs from medial temporal lobe structures, including the hippocampus and amygdala and the dopamine-rich ventral midbrain to drive goal-directed behavior (Goto and Grace, 2005, 2008; Gruber et al, 2009; Sesack and Grace, 2010). Though functional neuroimaging studies have not yet resolved the influences of these posterior structures on BART performance in human beings, it remains possible that they exert independent and interactive effects on network function in striatal subregions to control different aspects of behavioral performance.

Validity of the Rat BART

The value of behavioral measures of risk taking in human beings has been their potential as prognostic indicators of real-world high-risk behaviors (Lejuez et al, 2002, 2003), though they measure only one dimension of temperament likely relevant to this vulnerability (Daughters et al, 2009). That being the case, the rodent model represents a powerful opportunity to identify molecular and systems-level biomarkers for this susceptibility, as well as to further interrogate the causal function for these biomarkers in behavioral phenotypes. Although individual differences in a laboratory measure of risk-taking behavior in rats may not directly relate to predisposition to self-administer illicit drugs (because drug consumption does not carry the same sociocultural and perceived health risks in rats that it does in human beings), it still represents a model system in which to detect the signature of liability to taking risks, and to explore the neural mechanisms by which that signature reflects predisposition to pursue risky circumstances. Recent studies indicate that individual variation in aspects of pre- and post-synaptic dopamine function may determine impulsive risk-taking behavior (Cools et al, 2007; Dalley et al, 2007; James et al, 2007; Zald et al, 2008; Forbes et al, 2009), though these mechanisms probably represent only a fraction of the molecular influences on high-risk behaviors.

The data provided here support the face and construct validity of the rat-BART task. In human beings, performance on the BART is typically risk averse. For example, in their initial studies, Lejuez et al (2002, 2003, 2007) report mean and standard deviations for pumps per trial that reveal at least 95% of all individuals exhibit response profiles that are below the predicted, optimal mean level of responding that is predicted from the risk schedule imposed (Hunt et al, 2005); in this sense, rats and human beings seem to perform in the context of their respective versions of the task in very similar ways. Furthermore, the experimental manipulations performed here establish construct validity for the task by showing that behavioral decision making depends on both risk- and payoff-sensitive processes in a manner predicted by the theoretical basis of the task. This raises the potential for predictive validity (that rat and human behavior will respond to similar manipulations); however, this is not yet established based on the dataset presented here.

Recent work has begun to illustrate the situations under which BART performance is subject to pharmacological or environmental modification. For example, oxycodon, pramipexole, and bupropion have been reported to have no effect on BART performance (Acheson and de Wit, 2008; Hamidovic et al, 2008; Zacny and de Wit, 2009), whereas amphetamine exerts effects that depend on trait differences in reward sensitivity (White et al, 2007). Moreover, there are sex differences in performance, which are magnified by an acute stress challenge (Lighthall et al, 2009). These studies represent potentially interesting ways to validate environmental influences on risky-choice behavior in the rat BART.

A recent study in human beings indicated that heritability of BART performance was 0.55 (Anokhin et al, 2009), indicating that it is likely that there is also a moderately large genetic influence on performance. Interestingly, the out-bred rat strain studied here exhibits relatively large intersubject variation in performance (Figure 3a). Owing to this, rodents represent a powerful model system in which to study the genetic and genomic determinants of these individual differences, using either whole genome or candidate gene approaches. Beyond this, the development of a version of the BART task suitable for mice will enable candidate gene studies using transgenic and mutant models.

Translational research on the neurobiology of the ‘at-risk’ phenotype will be substantially aided by convergent studies of human beings and laboratory animals performing analog risk tasks, such as the one described here. Through study of the molecular and network mechanisms guiding adaptive decision making, new insights into the mechanisms by which genetic and environmental factors sculpt behavioral and temperamental profiles can be identified and new interventions (both behavioral and pharmaceutical) can be created. More importantly, biomarkers of this phenotype can be identified, permitting prevention research and policy to be implemented in the context of biologically tractable mechanisms and hypotheses.

References

Acheson A, de Wit H (2008). Bupropion improves attention but does not affect impulsive behavior in healthy young adults. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 16: 113–123.

Acton GS (2003). Measurement of impulsivity in a hierarchical model of personality traits: implications for substance use. Subst Use Misuse 38: 67–83.

Aklin WM, Lejuez CW, Zvolensky MJ, Kahler CW, Gwadz M (2005). Evaluation of behavioral measures of risk taking propensity with inner city adolescents. Behav Res Ther 43: 215–228.

Anokhin AP, Golosheykin S, Grant J, Heath AC (2009). Heritability of risk-taking in adolescence: a longitudinal twin study. Twin Res Hum Genet 12: 366–371.

Berendse HW, Galis-de Graaf Y, Groenewegen HJ (1992). Topographical organization and relationship with ventral striatal compartments of prefrontal corticostriatal projections in the rat. J Comp Neurol 316: 314–347.

Bickel WK, Miller ML, Yi R, Kowal BP, Lindquist DM, Pitcock JA (2007). Behavioral and neuroeconomics of drug addiction: competing neural systems and temporal discounting processes. Drug Alcohol Depend 90 (Suppl 1): S85–S91.

Bornovalova MA, Cashman-Rolls A, O’Donnell JM, Ettinger K, Richards JB, deWit H et al (2009). Risk taking differences on a behavioral task as a function of potential reward/loss magnitude and individual differences in impulsivity and sensation seeking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 93: 258–262.

Brown VJ, Bowman EM (2002). Rodent models of prefrontal cortical function. Trends Neurosci 25: 340–343.

Cools R, Sheridan M, Jacobs E, D’Esposito M (2007). Impulsive personality predicts dopamine-dependent changes in frontostriatal activity during component processes of working memory. J Neurosci 27: 5506–5514.

Crowley MJ, Wu J, Crutcher C, Bailey CA, Lejuez CW, Mayes LC (2009). Risk-taking and the feedback negativity response to loss among at-risk adolescents. Dev Neurosci 31: 137–148.

Dalley JW, Mar AC, Economidou D, Robbins TW (2008). Neurobehavioral mechanisms of impulsivity: fronto-striatal systems and functional neurochemistry. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 90: 250–260.

Dalley JW, Fryer TD, Brichard L, Robinson ES, Theobald DE, Laane K et al (2007). Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptors predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science 315: 1267–1270.

Daughters SB, Reynolds EK, MacPherson L, Kahler CW, Danielson CK, Zvolensky M et al (2009). Distress tolerance and early adolescent externalizing and internalizing symptoms: the moderating role of gender and ethnicity. Behav Res Ther 47: 198–205.

Floresco SB, St Onge JR, Ghods-Sharifi S, Winstanley CA (2008). Cortico-limbic-striatal circuits subserving different forms of cost-benefit decision making. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 8: 375–389.

Forbes EE, Brown SM, Kimak M, Ferrell RE, Manuck SB, Hariri AR (2009). Genetic variation in components of dopamine neurotransmission impacts ventral striatal reactivity associated with impulsivity. Mol Psychiatry 14: 60–70.

Goto Y, Grace AA (2005). Dopaminergic modulation of limbic and cortical drive of nucleus accumbens in goal-directed behavior. Nat Neurosci 8: 805–812.

Goto Y, Grace AA (2008). Limbic and cortical information processing in the nucleus accumbens. Trends Neurosci 31: 552–558.

Gruber AJ, Hussain RJ, O’Donnell P (2009). The nucleus accumbens: a switchboard for goal-directed behaviors. PLoS One 4: e5062.

Hamidovic A, Kang UJ, de Wit H (2008). Effects of low to moderate acute doses of pramipexole on impulsivity and cognition in healthy volunteers. J Clin Psychopharmacol 28: 45–51.

Hare TA, Camerer CF, Rangel A (2009). Self-control in decision-making involves modulation of the vmPFC valuation system. Science 324: 646–648.

Hunt MK, Hopko DR, Bare R, Lejuez CW, Robinson EV (2005). Construct validity of the Balloon Analog Risk Task (BART): associations with psychopathy and impulsivity. Assessment 12: 416–428.

James AS, Groman SM, Seu E, Jorgensen M, Fairbanks LA, Jentsch JD (2007). Dimensions of impulsivity are associated with poor spatial working memory performance in monkeys. J Neurosci 27: 14358–14364.

Kathleen Holmes M, Bearden CE, Barguil M, Fonseca M, Serap Monkul E, Nery FG et al (2009). Conceptualizing impulsivity and risk taking in bipolar disorder: importance of history of alcohol abuse. Bipolar Disord 11: 33–40.

Lejuez CW, Aklin W, Daughters S, Zvolensky M, Kahler C, Gwadz M (2007). Reliability and validity of the youth version of the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART-Y) in the assessment of risk-taking behavior among inner-city adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 36: 106–111.

Lejuez CW, Aklin WM, Zvolensky MJ, Pedulla CM (2003). Evaluation of the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) as a predictor of adolescent real-world risk-taking behaviours. J Adolesc 26: 475–479.

Lejuez CW, Read JP, Kahler CW, Richards JB, Ramsey SE, Stuart GL et al (2002). Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART). J Exp Psychol Appl 8: 75–84.

Lighthall NR, Mather M, Gorlick MA (2009). Acute stress increases sex differences in risk seeking in the balloon analogue risk task. PLoS One 4: e6002.

Llewellyn DJ (2008). The psychology of risk taking: toward the integration of psychometric and neuropsychological paradigms. Am J Psychol 121: 363–376.

Mar AC, Robbins TW (2007). Delay discounting and impulsive choice in the rat. Curr Protoc Neurosci Chapter 8: Unit 8.22.

Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES (1995). Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol 51: 768–774.

Platt ML, Huettel SA (2008). Risky business: the neuroeconomics of decision making under uncertainty. Nat Neurosci 11: 398–403.

Preuss TM (1995). Do rats have prefrontal cortex? The Rose-Woolsey-Akert program reconsidered. J Cogn Neurosci 7: 1–24.

Rao H, Korczykowski M, Pluta J, Hoang A, Detre JA (2008). Neural correlates of voluntary and involuntary risk taking in the human brain: an fMRI Study of the Balloon Analog Risk Task (BART). Neuroimage 42: 902–910.

Rivalan M, Ahmed SH, Dellu-Hagedorn F (2009). Risk-prone individuals prefer the wrong options on a rat version of the iowa gambling task. Biol Psychiatry 66: 743–749.

Schilman EA, Uylings HB, Galis-de Graaf Y, Joel D, Groenewegen HJ (2008). The orbital cortex in rats topographically projects to central parts of the caudate-putamen complex. Neurosci Lett 432: 40–45.

Sesack SR, Grace AA (2010). Cortico-basal ganglia reward network: microcircuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 27–47.

Sesack SR, Pickel VM (1992). Prefrontal cortical efferents in the rat synapse on unlabeled neuronal targets of catecholamine terminals in the nucleus accumbens septi and on dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. J Comp Neurol 320: 145–160.

St Onge JR, Floresco SB (2009). Prefrontal cortical contribution to risk-based decision making. Cereb Cortex (in press).

Trepel C, Fox CR, Poldrack RA (2005). Prospect theory on the brain? Toward a cognitive neuroscience of decision under risk. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 23: 34–50.

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 211: 453–458.

van den Bos R, Lasthuis W, den Heijer E, van der Harst J, Spruijt B (2006). Toward a rodent model of the Iowa gambling task. Behav Res Methods 38: 470–478.

Walton ME, Kennerley SW, Bannerman DM, Phillips PE, Rushworth MF (2006). Weighing up the benefits of work: behavioral and neural analyses of effort-related decision making. Neural Netw 19: 1302–1314.

Weber E, Blais A, Betz N (2002). A domain-specific risk-attitude scale: measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. J Behav Decis Mak 15: 263–290.

White TL, Lejuez CW, de Wit H (2007). Personality and gender differences in effects of d-amphetamine on risk taking. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 15: 599–609.

White TL, Lejuez CW, de Wit H (2008). Test-retest characteristics of the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART). Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 16: 565–570.

Wilhelm CJ, Mitchell SH (2008). Rats bred for high alcohol drinking are more sensitive to delayed and probabilistic outcomes. Genes Brain Behav 7: 705–713.

Winstanley CA, Dalley JW, Theobald DE, Robbins TW (2004). Fractionating impulsivity: contrasting effects of central 5-HT depletion on different measures of impulsive behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 29: 1331–1343.

Zacny JP, de Wit H (2009). The prescription opioid, oxycodone, does not alter behavioral measures of impulsivity in healthy volunteers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 94: 108–113.

Zald DH, Cowan RL, Riccardi P, Baldwin RM, Ansari MS, Li R et al (2008). Midbrain dopamine receptor availability is inversely associated with novelty-seeking traits in humans. J Neurosci 28: 14372–14378.

Zeeb FD, Robbins TW, Winstanley CA (2009). Serotonergic and dopaminergic modulation of gambling behavior as assessed using a novel rat gambling task. Neuropsychopharmacology 34: 2329–2343.

Zuckerman M, Eysenck S, Eysenck HJ (1978). Sensation seeking in England and America: cross-cultural, age, and sex comparisons. J Consult Clin Psychol 46: 139–149.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by Public Health Service grants P20-DA022539, P50-MH077248, and RL1-MH083270, and by Philip Morris USA. We gratefully acknowledge the advice and input of Drs Edythe London, Adriana Galvan, and Russell Poldrack.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jentsch, J., Woods, J., Groman, S. et al. Behavioral Characteristics and Neural Mechanisms Mediating Performance in a Rodent Version of the Balloon Analog Risk Task. Neuropsychopharmacol 35, 1797–1806 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2010.47

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2010.47

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Uncovering the structure of self-regulation through data-driven ontology discovery

Nature Communications (2019)

-

Neurons in rat orbitofrontal cortex and medial prefrontal cortex exhibit distinct responses in reward and strategy-update in a risk-based decision-making task

Metabolic Brain Disease (2019)

-

Extending the Balloon Analogue Risk Task to Assess Naturalistic Risk Taking via a Mobile Platform

Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment (2018)

-

Risk should be objectively defined: comment on Pelé and Sueur

Animal Cognition (2014)

-

Greater risk sensitivity of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in young smokers than in nonsmokers

Psychopharmacology (2013)