Abstract

Recent evidence suggests that corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) receptor (CRFR) signaling is involved in modulating binge-like ethanol consumption in C57BL/6J mice. In this report, a series of experiments were performed to further characterize the role of CRFR signaling in binge-like ethanol consumption. The role of central CRFR signaling was assessed with intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) infusion of the nonselective CRFR antagonist, α-helical CRF9–41 (0, 1, 5, 10 μg/1 μl). The contribution of central CRF type 2 receptor (CRF2R) signaling was assessed with i.c.v. infusion of the selective CRF2R agonist, urocortin (Ucn) 3 (0, 0.05, 0.1, or 0.5 μg/1 μl). The role of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis was assessed by pretreating mice with intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of (1) the corticosterone synthesis inhibitor, metyrapone (0, 50, 100, 150 mg/kg) or (2) the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, mifepristone (0, 25, 50 mg/kg), and (3) by using radioimmunoassay to determine whether binge-like ethanol intake influenced plasma corticosterone levels. Finally, we determined whether the ability of the CRF1R antagonist, CP-154,526 (CP; 0, 10, 15 mg/kg, i.p.), to blunt binge-like drinking required normal HPA axis signaling by comparing the effectiveness of CP in adrenalectomized (ADX) and normal mice. Results showed that i.c.v. infusion of a 1 μg dose of α-helical CRF9–41 significantly attenuated binge-like ethanol consumption relative to vehicle treatment, and i.c.v. infusion of Ucn 3 dose-dependently blunted binge-like drinking. On the other hand, metyrapone nonselectively reduced both ethanol and sucrose consumption, mifepristone did not alter ethanol drinking, and binge-like drinking did not correlate with plasma corticosterone levels. Finally, i.p. injection of CP significantly attenuated binge-like ethanol intake in both ADX and normal mice. Together, these results suggest that binge-like ethanol intake in C57BL/6J mice is modulated by CRF1R and CRF2R signaling, such that blockade of CRF1R or activation of CRF2R effectively reduces excessive ethanol intake. Furthermore, normal HPA axis signaling is not necessary to achieve binge-like drinking behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Binge drinking, a common term used to define excessive alcohol intake over a short period of time, has become a serious concern in the United States and worldwide (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2009). Binge drinking has been implicated in numerous health problems including heart disease, high blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes (Sundell et al, 2008; Toriola et al, 2009), and increases the proclivity to engage in other risky behaviors (Jonas et al, 2000; Ling et al, 2009; Nelson et al, 2009). Although binge drinking consistently ranks among the top adolescent risk behaviors (Eaton et al, 2008), emerging research indicates that a significant proportion of the adult population also engages in this behavior (Nelson et al, 2009). The potential societal impact of binge drinking is significant, as this pattern of ethanol consumption is believed to contribute to the development of ethanol dependence (Bonomo et al, 2004; Jennison, 2004; Keyes et al, 2008; Koob, 2000).

The ‘drinking in the dark’ (DID) procedure is an animal model of human binge drinking and has been used to identify neurochemical modulators of binge-like ethanol consumption (Koob, 2000; Rhodes et al, 2005, 2007; Sparta et al, 2008; Szumlinski et al, 2007). The DID procedure reliably generates high levels of voluntary ethanol consumption and corresponding blood–ethanol concentrations (BECs) over relatively short periods of time by providing ethanol-preferring C57BL/6J mice limited access to 20% ethanol solution beginning 3-h into the dark portion of the animals' light cycle (Rhodes et al, 2005). With DID procedures, animals typically achieve BECs above 80–100 mg per 100 ml over a 2–4 h period (Lyons et al, 2008; Rhodes et al, 2005, 2007). The BEC levels that are achieved in a short period of time are within ranges recently proposed in defining features of human binge drinking (National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism Advisory Council 2004; Courtney and Polich, 2009), suggesting that the DID procedure models important aspects of human binge drinking behavior. Importantly, C57BL/6J mice exhibit behavioral intoxication with DID procedures as measured by deficits in motor behavior in rotarod and balance beam tests (Rhodes et al, 2007). To date, dopaminergic (Kamdar et al, 2007), opioidergic (Kamdar et al, 2007), acetylcholinergic (Hendrickson et al, 2009), and glutamatergic (Gupta et al, 2008) signaling have been implicated in binge-like ethanol consumption using the DID paradigm.

Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and the urocortin (Ucn) peptides (Ucn1, Ucn2, and Ucn3) have been implicated in the modulation of multiple neurobiological systems, including those that regulate feeding, anxiety and depression, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis signaling, and ethanol consumption (Arborelius et al, 1999; Hauger et al, 2006; Heilig and Koob, 2007; Heinrichs and Richard, 1999; Kehne, 2007; Kuperman and Chen, 2008; Menzaghi et al, 1994; Ryabinin and Weitemier, 2006; Smith and Vale, 2006). CRF and the Ucn peptides produce their effects by binding to the G-protein-coupled CRF type 1 (CRF1R) and CRF type 2 (CRF2R) receptors. CRF binds to both receptors, but has greater affinity to the CRF1R (Hauger et al, 2006; Pioszak et al, 2008; Ryabinin et al, 2002). Although Ucn1 binds with equal affinity to both CRF1R and CRF2R, Ucn2 and Ucn3 are CRF2R agonists (Hauger et al, 2006; Pioszak et al, 2008; Ryabinin et al, 2002). CRF and the Ucn peptides are expressed ubiquitously throughout the brain, each with unique but overlapping expression profiles (Hauger et al, 2006; Imaki et al, 1996; Potter et al, 1994; Ryabinin et al, 2002). CRF and the Ucn peptides exert their behavioral and neuroendocrine actions through central hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic pathways (Hauger et al, 2006; Heilig and Koob, 2007; Heinrichs and Koob, 2004; Kehne, 2007; Koob and Le Moal, 2008; Ryabinin et al, 2002).

Recent evidence suggests that CRF receptor (CRFR) signaling modulates binge-like ethanol consumption (Sparta et al, 2008). Thus, pretreatment with intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of a peripherally bioavailable CRF1R antagonist, CP-154,526 (CP), attenuated excessive ethanol consumption in binge-like drinking C57BL/6J mice that achieved BECs of ∼80 mg per 100 ml, but failed to alter ethanol consumption by mice that drank moderate amounts of ethanol and achieved low BECs (∼40 mg per 100 ml or less). Furthermore, pretreatment with CP did not affect sucrose consumption, suggesting that CRF1R activity is selectively recruited by high levels of ethanol consumption (ie, those resulting in BECs greater than 80 mg per 100 ml). However, the mechanism by which CRFR signaling modulates binge-like ethanol drinking has not been investigated. Here, we show that the effects of CRFR antagonism on binge-like drinking are centrally mediated, and that activation of the CRF2R protects against binge-like ethanol intake. As ethanol exposure causes activation of the HPA axis through CRFR signaling and because HPA axis activity has been shown to modulate ethanol consumption in rodents (Krishnan et al, 1991; Morrow et al, 2006), we determined whether normal HPA axis signaling is necessary for the expression of binge-like ethanol drinking. We show that normal HPA axis activity is not necessary, and that CRF1R antagonist-induced reduction of binge-like drinking does not involve HPA axis signaling. These observations provide novel insight into the mechanism by which CRFR signaling modulates binge-like drinking behavior in C57BL/6J mice, and expand the literature by showing that CRF1R and CRF2R signaling are recruited during the early phases of excessive ethanol ingestion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice (n=191; Jackson Laboratories, Jackson, MS) were 6–8 weeks of age and weighed 18–26 g on arrival, and male C57BL/6J mice that underwent adrenalectomy (ADX; n=24; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) or sham surgery (SHAM; n=40; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were 8–10 weeks of age and weighed 15–26 g on arrival. As per instructions provided by Jackson Laboratories, ADX (and SHAM) mice were given access to a 0.9% saline solution for the first 4 days after arrival to help maintain sodium chloride balance. Mice were individually housed in plastic cages, were allowed to habituate to their environment for at least 1 week before the start of the experiments, and had ad libitum access to standard rodent chow and water except where noted. The colony room was maintained at approximately 22°C with a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle and lights went off at 1000 hours. All procedures used are in accordance with the National Institute of Health guidelines, and were approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drugs

Ethanol (20% v/v) solutions were prepared using tap water and 100% ethyl alcohol (Decon Laboratories Inc., King of Prussia, PA) and sucrose (w/v) solutions were prepared using tap water and D-sucrose (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). The nonselective CRF receptor antagonist, α-helical CRF9–41 (α-helical CRF; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO), was dissolved in sterile water and injected intracerebroventricularly (i.c.v.; vehicle, 1, 5, or 10 μg/1 μl) approximately 60 min before the start of behavioral testing. Doses and the time course were based on previous studies (Brauns et al, 2001; Nishikawa et al, 2004). In addition, α-helical CRF effectively blocks CRF-induced ACTH secretion in vitro and in vivo (Rivier et al, 1984), and attenuates CRF-induced adenylate cyclase activity (Battaglia et al, 1987). The selective CRF2R agonist, Ucn3 (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Inc., Burlingame, CA), was dissolved in sterile water and injected i.c.v. (vehicle, 0.05, 0.1, or 0.5 μg/1 μl) approximately 90 min before the start of behavioral testing. Doses and the time course were extrapolated from previous research (D'Anna et al, 2005; Valdez and Koob, 2004; Venihaki et al, 2004). Ucn3 is a highly selective agonist for CRF2R (Ki=9.1 nM) vs CRF1R (Ki>10 000 nM) (Hauger et al, 2006; Ryabinin et al, 2002). The corticosterone synthesis inhibitor, 2-Methyl-1,2-di-3-pyridyl-1-propanone (metyrapone; Sigma-Aldrich) was suspended in 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose (CMC; Sigma-Aldrich) and injected intraperitoneally (i.p; vehicle, 50, 100, or 150 mg/kg) approximately 30 min before the start of behavioral testing. The time course and dose range were based on previous data (Nair and Bonneau, 2006; O'Callaghan et al, 2005). Importantly, metyrapone has been shown to effectively deplete circulating plasma corticosterone levels under basal (Laborie et al, 1995, 1997) and stressed (Krugers et al, 2000) conditions. The glucocorticoid receptor antagonist mifepristone (also called RU38486; Sigma-Aldrich) was suspended in 0.5% CMC and dissolved by sonicating for 15 min, and was delivered i.p. (vehicle, 25, 50, or 100 mg/kg) approximately 30 min before the start of behavioral testing. Similar doses and time courses have been previously used (Koenig and Olive, 2004; O'Callaghan et al, 2005; Roberts et al, 1995). Mifepristone displays high binding affinity for the glucocorticoid type I receptor (Ki=0.4 nM), and mifepristone and its active metabolites are known to cross the blood–brain barrier (Heikinheimo et al, 1994; Peeters et al, 2004). The selective CRF1R antagonist, CP-154,526 (butyl-[2,5-dimethyl-7-(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-yl]-ethylamine) (CP; Pfizer, Groton, CT), was suspended in 0.5% CMC and injected approximately 60 min before the start of behavioral testing, as previously described (Sparta et al, 2008). This drug is bioavailable, crosses the blood brain barrier, and is highly selective for CRF1R (Ki=2.1 nM) vs CRF2R (Ki>10 μM) (Chen et al, 1997; Keller et al, 2002; Schulz et al, 1996).

‘Drinking in the Dark’ Procedure

A 4-day DID procedure was used in all experiments (Rhodes et al, 2005; Sparta et al, 2008). On days 1–3, beginning 2.5 h into the dark cycle, water bottles were removed from all cages. For all experiments involving i.p. drug administration, animals were weighed and injected with the appropriate volume (5 ml/kg) of the specified vehicle to habituate them to injections. For all experiments involving i.c.v. drug administration, animals were handled for 1 min/day on days 1–3. Beginning 3 h into the dark cycle, small ethanol bottles (or water bottles, where specified) were weighed (to the nearest 0.01 g) and placed on cages for 2 h (bottles were again weighed after removal to calculate consumption). The same schedule was followed on day 4, except that ethanol access was extended to 4 h and immediately thereafter, and tail blood samples were collected for analysis of BECs. For all experiments involving drug administration, animals were pretreated with the appropriate dose of drug before the ethanol access period on day 4.

Surgery and Infusion Procedures

Approximately 2 weeks after arrival, mice underwent surgery to implant cannulae aimed at the lateral ventricle. Specifically, mice were anesthetized with a cocktail of ketamine (117 mg/kg) and xylazine (7.92 mg/kg) and surgically implanted with a 26-gauge cannula (Plastic One, Roanoke, VA) aimed at the left lateral ventricle (0.2 mm posterior to bregma, 1.0 mm lateral to the midline, and 2.3 mm ventral to the skull surface) (Navarro et al, 2005). Mice were allowed to recover approximately 2 weeks before experimental procedures were started. Cannula placement was verified histologically at the end of the experiment. The i.c.v. infusions were given manually in a 1.0 μl volume over a 1-min period with a 1.0 μl Hamilton microsyringe. Mice were familiarized to infusion procedures 2–3 times before the i.c.v. experiments described below.

Blood–Ethanol Concentration

Approximately 10 μl of blood was collected from the tail vein of each mouse immediately following ethanol access on day 4 of the DID procedure to analyze for BEC. Samples were centrifuged, and 5 μl of plasma from each sample was analyzed (Analox Instruments, Lunenburg, MA).

Experiment 1: Effects of i.c.v. Administration of α-Helical CRF9–41 on Binge-Like Ethanol Consumption

Animals were assigned to groups equated for ethanol consumption during the first 3 days of DID procedures. On day 4, groups were given an i.c.v. infusion as described above. An additional set of ethanol-naive mice was used to assess the effects of α-helical CRF on consumption of a 10% sucrose solution, a concentration that has been used previously to assess the specificity of drug effects to ethanol consumption (Sparta et al, 2008). Access to the sucrose solution over 4 days followed the same DID procedures used with ethanol solution.

Experiment 2: Effects of i.c.v. Administration of Ucn3 on Binge-Like Ethanol Consumption

Animals were assigned to groups equated for ethanol consumption during the first 3 days of DID procedures, and on day 4 mice were given i.c.v. infusions as described above. A subset of these animals was then used to assess the effects of Ucn3 on consumption of a 10% sucrose solution using DID procedures.

Experiments 3 and 4: Effects of Mifepristone and Metyrapone on Binge-Like Ethanol Consumption

Mice were assigned to groups equated for ethanol consumption during the first 3 days of DID procedures, and on day 4 each group was given i.p. injection of mifepristone or vehicle as described above. Approximately 2 weeks later, these animals underwent a second round of DID procedures, as the mifepristone manipulation had no effect on DID ethanol intake (see Results section below). Mice were redistributed into groups equated for ethanol consumption on days 1–3. On day 4, mice were given i.p. injection of metyrapone or vehicle as described above. The effects of metyrapone on 4 h consumption of a 10% sucrose solution were assessed in an additional set of ethanol-naive animals. As peak brain levels of mifepristone and its metabolites are achieved within 1–2 h and eliminated by 4 h following peripheral administration (Heikinheimo et al, 1994), an additional set of ethanol-naive mice underwent DID procedures as described above, except that ethanol consumption was measured hourly throughout ethanol access on day 4.

Experiment 5: The Effects of Binge-Like Ethanol Consumption on Plasma Corticosterone Levels

Ethanol-naive mice were divided into two groups equated for body weight on arrival. During the 4-day DID procedure, one group was given access to a 20% ethanol solution, whereas the second group received water. Approximately 20 μl of blood was collected from the tail vein of each mouse immediately following the 4 h session on day 4 (7 h into the dark cycle). Samples were centrifuged, and plasma was removed and frozen at −20°C. Plasma corticosterone levels were assessed using 10 μl of plasma from each sample and a Radioimmuno Assay Kit (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) (Salling et al, 2008).

Experiment 6: The Effects of CP and ADX on Binge-Like Ethanol Consumption

ADX and SHAM mice were divided into groups equated for ethanol consumption during the first 3 days of the procedure and then given i.p. injections of vehicle or CP on day 4 (vehicle, 10, or 15 mg/kg). Two days later, the effects of adrenalectomy on 4 h consumption of a 3% sucrose solution were assessed in these mice.

Statistical Analysis

For all experiments, the first 3 days of ethanol consumption were analyzed using repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs), and the fourth day of ethanol (or sucrose) consumption and BECs were assessed using ANOVAs. When significant differences were observed, follow-up Bonferroni post hoc analyses were performed. A repeated measures ANOVA was performed to assess the hourly effects of mifepristone (hour × dose) over the 4 h test in which the hourly measures were collected. The relationship between day 4 ethanol consumption and BECs was assessed with Pearson's R correlations. In some cases, the amount of blood sample collected for BEC analyses were not adequate, and therefore were not included in the analyses. All data are expressed as mean±SEM, and significance was accepted at the p<0.05 level (two-tailed) for ANOVA and Bonferroni tests.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: Effects of i.c.v. Administration of α-helical CRF9–41 on Binge-Like Ethanol Consumption

Ethanol consumption

Ethanol consumption during the first 3 days of DID did not differ on the basis of drug treatment grouping (drug treatment: F(3, 30)=1.06, p=0.380; see Table 1). As shown in Figure 1a, ethanol consumption on the fourth day of the DID procedure was significantly affected by drug treatment (drug treatment: F(3, 31)=3.183, p=0.039), as were BECs (drug treatment: F(3, 31)=3.792, p=0.021; see Figure 1b). Bonferroni post hoc analyses reveal that animals pretreated with 1 μg of α-helical CRF consumed significantly less ethanol than did animals pretreated with vehicle and achieved significantly lower BECs. BECs corresponded with ethanol consumption, irrespective of α-helical CRF treatment (r=0.80, p<0.001).

The effects of α-helical CRF on (a) mean 4-h 20% ethanol consumption and (b) blood–ethanol concentrations (n=5–10 per group). (c) Effects of α-helical CRF on mean 4-h 10% sucrose consumption in C57BL/6J animals (n=10 per group). Data represent mean±SEM, and are normalized for body weight. *p<0.05 vs vehicle-treated group determined by Bonferroni post hoc analyses.

Sucrose consumption

Consumption of a 10% sucrose solution was not altered by pretreatment with 1 μg of α-helical CRF, as confirmed by the results of a one-way ANOVA (drug treatment: F(1, 19)=2.749, p=0.115; see Figure 1c).

Experiment 2: Effects of i.c.v. Administration of Ucn3 on Binge-Like Ethanol Consumption

Ethanol consumption

Ethanol consumption during the first 3 days of consumption did not differ on the basis of drug treatment grouping (drug treatment: F(3, 31)=0.23, p=0.87; see Table 1). As shown in Figure 2a, ethanol consumption on the fourth day of the DID procedure was dose-dependently affected by drug treatment (drug treatment: F(3, 30)=6.963, p=0.001), as were BECs (drug treatment: F(3, 30)=6.504, p=0.002; see Figure 2b). Bonferroni post hoc analyses revealed that animals pretreated with 0.1 or 0.5 μg of Ucn3 consumed significantly less ethanol than did animals pretreated with vehicle, and animals pretreated with all doses achieved significantly lower BECs. BECs corresponded with ethanol consumption, irrespective of Ucn3 treatment (r=0.85, p<0.001).

The effects of Ucn3 on (a) mean 4-h 20% ethanol consumption (b) and blood–ethanol concentrations (n=6–8 per group). (c) Effects of Ucn3 on mean 4-h 10% sucrose consumption in C57BL/6J animals (n=10 per group). Data represent mean±SEM, and are normalized for body weight. *p<0.05 vs vehicle-treated group determined by Bonferroni post hoc analyses.

Sucrose consumption

Consumption of a 10% sucrose solution was not altered by pretreatment with either 0.1 or 0.5 μg Ucn3, as confirmed by the results of a one-way ANOVA (drug treatment: F(2, 29)=2.615, p=0.092; see Figure 2c).

Experiment 3: Effects of Mifepristone on Binge-Like Ethanol Consumption

Ethanol consumption during the first 3 days of the DID procedure did not differ on the basis of drug treatment grouping (drug treatment: F(3, 36)=0.005, p=0.999; see Table 1). As shown in Figure 3a, ethanol consumption on the fourth day of the DID procedure was not altered by drug treatment (drug treatment: F(3, 37)=0.431, p=0.732). Likewise, hourly ethanol consumption on the fourth day of the DID procedure was not altered by drug treatment (drug treatment: F(2, 27)=0.637, p=0.536; see Figure 3b). Ethanol consumption did differ by hour (hour: F(31, 81)=10.552, p<0.001), though the interaction between drug treatment and hour was not significant (drug treatment × hour: F(6, 81)=1.070, p=0.387). BECs correlated significantly with ethanol consumption (r=0.74, p<0.001; data not shown), and were unaffected by drug treatment (drug treatment: F(3, 37)=0.220, p=0.882; data not shown).

Effects of mifepristone on (a) mean 4-h 20% ethanol consumption (n=8–10 per group), and (b) mean hourly 20% ethanol consumption (n=10 per group). The effects of metyrapone on (c) mean 4-h 20% ethanol consumption (n=9 per group), and (d) mean 4-h 10% sucrose consumption (n=7–8 per group). (e) Effects of 4-h 20% ethanol consumption or water consumption on mean plasma corticosterone levels, and (f) correlations between plasma corticosterone levels and 4-h 20% ethanol consumption, in C57BL/6J animals (n=15 per group). Data represent mean±SEM, and are normalized for body weight. *p<0.05 vs vehicle-treated group determined by Bonferroni post hoc analyses.

Experiment 4: Effects of Metyrapone on Binge-Like Ethanol Consumption

Ethanol consumption

Ethanol consumption during the first 3 days of the DID procedure did not differ on the basis of drug treatment grouping (drug treatment: F(3, 32)=0.922, p=0.922; see Table 1). As shown in Figure 3c, ethanol consumption on day 4 was significantly and dose-dependently altered by drug treatment (drug treatment: F(3, 35)=16.468, p<0.001), as were BECs (drug treatment: F(3, 34)=11.200, p<0.001; data not shown). Bonferroni post hoc analyses reveal that animals pretreated with 100 mg/kg or 150 mg/kg of metyrapone consumed significantly less ethanol than did animals pretreated with vehicle, and achieved significantly lower BECs (data not shown). BECs corresponded with the dose-dependent attenuation of ethanol consumption by metyrapone (r=0.74, p<0.001).

Sucrose consumption

Consumption of a 10% sucrose solution was significantly altered by pretreatment with metyrapone, as confirmed by the results of a one-way ANOVA (drug treatment: F(2, 22)=13.055, p<0.001; see Figure 3d). Bonferroni post hoc analyses reveal that animals pretreated with 100 or 150 mg/kg consumed significantly less of the 10% sucrose solution than did animals pretreated with vehicle.

Experiment 5: The Effects of Binge-Like Ethanol Consumption on Plasma Corticosterone Levels

As shown in Figure 3e, plasma corticosterone levels were not significantly altered by ethanol consumption compared with water consumption after 4 h of ethanol access (F(1, 29)=0.202, p=0.657). Plasma corticosterone levels were not significantly correlated to ethanol consumption (r=−0.12, p=0.330; see Figure 3f).

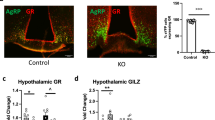

Experiment 6: The Effects of CP and ADX on Binge-Like Ethanol Consumption

A repeated measures ANOVA was performed on body weight data over the 4 days of DID procedures to determine whether ADX had a negative impact on the health of mice. Relative to SHAM-treated mice (22.73±0.27 g), ADX mice (22.24±0.35 g) did not show altered body weight over the 4-day procedure, suggesting that ADX mice remained healthy over the course of the experiment.

Ethanol consumption

The results of a repeated measures ANOVA reveal a significant main effect of surgery on ethanol consumption during the first 3 days of the DID procedure (surgery condition: F(1, 58)=9.995, p=0.002; see Figure 4a), but no effect based on drug treatment grouping (F(2, 58)=0.027, p=0.973; data not shown). As shown in Figure 4b, pretreatment with CP significantly altered ethanol consumption by both ADX and SHAM animals on day 4 (drug treatment: F(2, 58)=13.827, p<0.001). The main effects of surgery and the interaction between surgery condition and drug treatment were not significant on day 4 (surgery condition: F(1, 58)=3.090, p=0.084; surgery condition × drug treatment: F(2, 28)=1.332, p=0.272). Bonferroni post hoc analyses reveal that pretreatment with either the 10 or 15 mg/kg dose of CP significantly attenuated ethanol consumption relative to vehicle treatment in both ADX and SHAM animals.

(a) Effects of adrenalectomy on mean 2-h 20% ethanol consumption by C57BL/6J animals during the first 3 days of the DID procedure (n=24–40 per group). Effects of CP on (b) mean 4-h 20% ethanol consumption, and (c) blood–ethanol concentrations by ADX or SHAM C57BL/6J animals on day 4 (n=8–14 per group). (d) Effects of adrenalectomy on mean 2-h 3% sucrose consumption by C57BL/6J animals (n=23–40). Data represent mean±SEM, and are normalized for body weight. *p<0.05 vs vehicle-treated group, +p<0.05 vs SHAM group, determined by Bonferroni post hoc analyses.

Blood–ethanol concentrations

Results indicated a significant main effect of surgery (surgery condition: F(1, 58)=6.323, p=0.015), in addition to a significant main effect of drug (drug treatment: F(2, 58)=8.724, p<0.001), on BECs achieved on day 4 of the DID procedure. The interaction between these two factors was not significant (surgery condition × drug treatment: F(2, 58)=0.045, p=0.956). Bonferroni post hoc analyses reveal that ADX animals achieved lower BECs relative to SHAM animals (see Figure 4c). In agreement with the ethanol consumption data, Bonferroni post hoc analyses also reveal that pretreatment with either the 10 or 15 mg/kg doses of CP significantly attenuated BECs in both ADX and SHAM animals.

Sucrose consumption

Consumption of a 3% sucrose solution was significantly attenuated in ADX animals relative to SHAM animals (surgery condition: F(1, 62)=12.153, p=0.001; see Figure 4d).

DISCUSSION

The current results indicate that central CRFR signaling modulates binge-like ethanol drinking in mice, and show that both CRF1R and CRF2R are involved. Furthermore, the present results are not consistent with a role for HPA axis signaling in the modulation of binge-like drinking, and show that the effects of CRF1R antagonism on binge-like drinking do not require normal HPA axis function. These conclusions are based on the following observations: (1) i.c.v. administration of a nonselective CRFR antagonist attenuated binge-like drinking, (2) i.c.v. infusion of the CRF2R agonist, Ucn3, dose-dependently reduced binge-like drinking, (3) manipulation of the HPA axis independent of CRF antagonism (ie, blockade of glucocorticoid receptor or inhibition of corticosterone synthesis with administration of metyrapone or ADX) failed to selectively protect against binge-like ethanol consumption, (4) binge-like ethanol drinking did not influence plasma corticosterone levels in mice, and (5) pretreatment with CP, a CRF1R antagonist, attenuated ethanol consumption to a similar degree in both ADX- and SHAM-treated mice, showing that CP-induced reduction of binge-like ethanol drinking does not require normal HPA axis signaling. These observations provide novel insights into the mechanisms by which CRFR signaling modulates binge-like drinking behavior in C57BL/6J mice.

The observation that central CRFR signaling modulates binge-like ethanol consumption complements the current literature indicating an integral role for central CRFRs in the modulation of neurobiological responses to ethanol. For example, the central administration of nonselective CRFR antagonists has previously been shown to attenuate increased ethanol consumption (Finn et al, 2007; Funk et al, 2006; Valdez et al, 2002) and relapse of ethanol-seeking behavior (Le et al, 2002; Liu and Weiss, 2002) in ethanol-dependent rodents. In addition, there are examples of a role for CRFR signaling in non-dependent ethanol drinking, as CRF1R antagonists have been shown to attenuate deprivation-induced drinking in mice (Sparta et al, 2009), stress-induced drinking in rats and mice (Lowery et al, 2008; Overstreet et al, 2007), and the acquisition of ethanol consumption in isolation-reared rats (Lodge and Lawrence, 2003). It should be noted that a recent report failed to find an effect of a CRF1R antagonist on binge-like drinking using a rat model (Ji et al, 2008). However, in addition to species differences, Ji et al (2008) used a sweetened alcohol solution to induce increased ethanol drinking in their paradigm.

Central infusion of the nonselective CRFR antagonist α-helical CRF did not attenuate ethanol consumption in a dose-dependent manner in this report, a finding that is in agreement with a previous observation of biphasic effects of α-helical CRF on reinstatement to heroin-seeking behavior, where lower doses (eg, 3 μg) attenuated reinstatement and higher doses (eg, 10 μg) had no effect on behavior (Shaham et al, 1997). Similar biphasic effects of this drug have also been noted for anxiety-like behavior induced by ethanol withdrawal (Menzaghi et al, 1994; Rassnick et al, 1993) or stress (Heinrichs et al, 1994). Such biphasic effects of α-helical CRF on behavior may be due in part to this drug's actions as a partial agonist at the CRF1R with increasing doses (Smart et al, 1999). As central administration of CRF promotes hyperactivity and stereotyped behavior (Matsuzaki et al, 1989; Song et al, 1995, 1997; Terawaki et al, 2004; Veldhuis and De Wied, 1984), it is possible that hyperactivity in mice that received the 10 μg dose of α-helical CRF caused ethanol spillage, which would account for low BECs in this group despite what appeared to be high levels of ethanol intake. Importantly, here we provide novel evidence that central CRF2R signaling also modulates binge-like ethanol drinking, as central infusion of the highly selective CRF2R agonist Ucn3 attenuated binge-like ethanol consumption in C57BL/6J mice. It should be noted that central CRFR signaling appears to selectively modulate binge-like ethanol drinking, rather than consumption of other reinforcing/caloric substances in general, as doses of centrally infused drugs (ie, 1 μg of α-helical CRF, and 0.1 and 0.5 μg of Ucn3) that effectively reduced 20% ethanol consumption did not have effects on 10% sucrose consumption.

The present results with central infusion of the CRF2R agonist, Ucn3, are consistent with those obtained with the CRF1R and CRF2R agonist, Ucn1, which, when delivered into the lateral septum (an area densely populated with CRF2R), also blunted binge-like drinking in mice (Ryabinin et al, 2008). To date, blockade of the CRF1R with CP-154,526 (here and Sparta et al, 2008), activation of CRF1R and/or CRF2R in the lateral septum with site-directed infusion of Ucn1 (Ryabinin et al, 2008), and activation of CRF2R with Ucn3 (in this report) are all treatments that protect against binge-like ethanol drinking in C57BL/6J mice. Taken together, the most parsimonious mechanism based on the current data is one in which CRF1R activation promotes, and CRF2R activation blunts, binge-like ethanol drinking. It will be important to determine which endogenous ligands (CRF and the Ucn peptides) and which brain regions (in addition to the lateral septum) are involved.

Corticotropin-releasing factor activity is known to have significant effects on HPA axis signaling as well as extrahypothalamic brain systems, though its role in ethanol-related behaviors appear to be primarily mediated extrahypothalamically (Koob, 2003, 2008). The current results obtained using various experimental manipulations of the HPA axis suggest that binge-like ethanol drinking by C57BL/6J is not likely modulated by HPA axis signaling. First, blunted HPA axis signaling attributed to adrenalectomy or pretreatment with metyrapone, a corticosterone synthesis inhibitor, nonselectively reduced both ethanol and sucrose consumption. These results are in agreement with previous studies indicating that adrenalectomy reduces both voluntary ethanol (Fahlke et al, 1995) and sucrose consumption (Seidenstadt and Eaton, 1978). Likewise, metyrapone has also been shown to reduce ethanol consumption at similar doses (Fahlke et al, 1994; O'Callaghan et al, 2005), and corticosterone signaling has been implicated in the self-administration of other drugs of abuse, including cocaine (Goeders and Guerin, 1996, 2008) and amphetamine (Piazza et al, 1991). Taken together, these data suggest that HPA axis signaling may generally modulate the self-administration of substances with reinforcing properties.

The second point suggesting that HPA axis signaling is not necessary for the expression of binge-like ethanol drinking is the observation that pretreatment with mifepristone, a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, did not alter binge-like ethanol consumption at any of the doses tested. Although one investigation did report dose-dependent attenuation of 1-h ethanol consumption following peripheral pretreatment with 1–20 mg/kg doses of mifepristone (Koenig and Olive, 2004), several other investigations, in addition to this report, have found that the blockade of glucocorticoid receptors does not alter ethanol consumption (Fahlke et al, 1995, 1996; O'Callaghan et al, 2005; Yang et al, 2008). Although it has been reported that mifepristone is rapidly metabolized in several species, including rats (Peeters et al, 2004), it is unlikely that this factor accounts for the observed lack of effect on binge-like ethanol drinking because hourly measurements of binge-like ethanol drinking also failed to show an effect of mifepristone. On the basis of the study by Koenig and Olive (2004), it is possible that mifepristone would have effectively reduced binge-like ethanol consumption had a lower dose range been used. However, this is unlikely as attenuation of ethanol consumption was greatest at the highest dose tested (20 mg/kg) (Koenig and Olive, 2004), and yet no alterations in ethanol consumption were observed after administration of a 25 mg/kg dose of mifepristone in this study. Furthermore, the literature indicates that mifepristone is most efficacious at high doses when administered peripherally as this compound does not readily cross the blood–brain barrier (Peeters et al, 2004). Although the factors that contribute to the inconsistencies between the Koenig and Olive, (2004) study and this report are not clear, one straightforward interpretation is that glucocorticoid receptor signaling modulates limited access ethanol consumption by rats, but not binge-like ethanol drinking in C57BL/6J mice.

The third point suggesting that HPA axis signaling does not modulate binge-like drinking is the observation that binge-like ethanol intake did not alter circulating levels of corticosterone in C57BL/6J mice relative to mice drinking water. As corticosterone is often used as a marker of HPA axis activity (Richardson et al, 2008), these results suggest that binge-like ethanol consumption is not driven by heightened HPA axis activity. Although 4-h of binge-like ethanol drinking did not alter plasma corticosterone levels in this study, some reports have shown robust increases in circulating corticosterone following ethanol administration through multiple routes, including intravenous (Richardson et al, 2008), intragastric (Lee and Rivier, 1997; Ogilvie et al, 1997), and i.p. (Ogilvie et al, 1997) ingestion in the form of ethanol diet (Ogilvie et al, 1997), and self-administration (Richardson et al, 2008). Although these results suggest that ethanol can stimulate HPA axis activity, such activity appears to be sensitive to the time of day. Thus, the effects of ethanol administration on corticosterone levels have primarily been observed during the animals' light cycle, when basal corticosterone levels are typically low relative to corticosterone levels during the dark cycle (Loh et al, 2008). Although one recent report describes ethanol-induced increases in plasma corticosterone during the dark cycle (Richardson et al, 2008), it is difficult to draw direct comparisons with this study as different species (rats vs mice) and routes of ethanol administration (intravenous vs ethanol drinking) were used.

It should be noted that binge-like ethanol intake may have triggered an increase in plasma corticosterone levels, but such increases may have been transient and thus missed at the sampling time used (4 h after the initiation of ethanol consumption on the fourth day of ethanol access). For example, it is possible that ethanol-induced increases of plasma corticosterone occur transiently toward the beginning of ethanol consumption and thus returned to baseline levels before the blood samples were collected 4 h after ethanol consumption began. It is also possible that mice develop tolerance to ethanol-induced increases of plasma corticosterone levels, and that such tolerance may have been complete by the fourth day of ethanol access. Nonetheless, the converging data set suggest that normal HPA axis signaling is not necessary for the expression of binge-like drinking in C57BL/6J mice, and as noted above, CRF1R blockade appears to blunt binge-like drinking without involving the HPA axis.

According to the allostasis model of ethanol dependence (Koob and Kreek, 2007; Koob, 2003, 2008), repeated exposure to, and withdrawal from, high amounts of ethanol lead to functionally significant neuroadaptations that translate into persistent increases of anxiety, craving for ethanol, and ultimately excessive ethanol intake. Some of the most well-characterized neuroadaptations resulting from a history of ethanol exposure occur within the CRF system of the extended amygdala (Ciccocioppo et al, 2006; Funk et al, 2006; Merlo Pich et al, 1995; Olive et al, 2002; Zorrilla et al, 2001). Evidence includes increased amygdalar CRF immunoreactivity (Funk et al, 2006; Pich et al, 1995; Zorrilla et al, 2001), increased dialysate CRF levels (Olive et al, 2002), and increased amygdalar expression of the CRF1R (Sommer et al, 2008), following experimental induction of ethanol dependence. Therefore, imbalances in CRF signaling characterize the neurobiology of ethanol dependence. Our results provide evidence of a role for CRFR signaling in binge-like ethanol consumption, a behavior that is proposed to be a gateway to ethanol dependence (Koob, 2003). Importantly, the current data, and work that assessed deprivation-induced increases of ethanol consumption (Sparta et al, 2009), suggest that CRFR signaling is engaged early in the transition to ethanol dependence. An interesting possibility is that repeated ethanol binges lead to the development of ethanol dependence by inducing significant neuroadaptations in the CRF and/or Ucn systems. Viewed this way, repeated activation of the central CRF system with repeated episodes of binge drinking progressively leads to neuroadaptive (allostatic) alterations in CRF receptor signaling, which culminates in ethanol dependence.

In conclusion, this study provides novel insights into the mechanisms by which CRFR signaling modulates binge-like ethanol consumption. The present findings, in tandem with previous reports (Sparta et al, 2008; Ryabinin et al, 2008), suggest that central CRFR signaling modulates excessive binge-like ethanol intake without influencing ethanol intake in mice drinking moderate amounts of ethanol and which achieve modest BECs. In addition, both CRF1R and CRF2R appear to be involved. On the other hand, HPA axis signaling does not appear to be a mechanism that is necessary for (or specific to) the expression of binge-like ethanol drinking in C57BL/6J mice, or for CRF1R antagonism-induced blunting of binge-like ethanol intake. Future research is needed to identify the brain regions in which CRFR signaling is recruited during binge-like ethanol consumption, and to determine the roles of CRF and the Ucn family of peptides in modulating this behavior. Finally, the present observations reinforce and expand the current literature by showing that CRF1R and CRF2R signaling are recruited during the early phases of excessive ethanol ingestion. A recent study reported genetic linkage between polymorphisms of the corticotropin releasing hormone 1 receptor gene and binge drinking in humans (Treutlein et al, 2006). An exciting possibility is that CRF1R antagonists and CRF2R agonists, in addition to having potential therapeutic value in treating ethanol dependence, may also be attractive targets for treating binge drinking and preventing the transition to dependence in humans.

References

Arborelius L, Owens MJ, Plotsky PM, Nemeroff CB (1999). The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in depression and anxiety disorders. J Endocrinol 160: 1–12.

Battaglia G, Webster EL, De Souza EB (1987). Characterization of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor-mediated adenylate cyclase activity in the rat central nervous system. Synapse 1: 572–581.

Bonomo YA, Bowes G, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Patton GC (2004). Teenage drinking and the onset of alcohol dependence: a cohort study over seven years. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 99: 1520–1528.

Brauns O, Liepold T, Radulovic J, Spiess J (2001). Pharmacological and chemical properties of astressin, antisauvagine-30 and alpha-helCRF: significance for behavioral experiments. Neuropharmacology 41: 507–516.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2009). Sociodemographic differences in binge drinking among adults—14 States, 2004. MMWR Surveill Summ 58: 301–304.

Chen YL, Mansbach RS, Winter SM, Brooks E, Collins J, Corman ML et al (1997). Synthesis and oral efficacy of a 4-(butylethylamino)pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine: a centrally active corticotropin-releasing factor1 receptor antagonist. J Med Chem 40: 1749–1754.

Ciccocioppo R, Economidou D, Cippitelli A, Cucculelli M, Ubaldi M, Soverchia L et al (2006). Genetically selected Marchigian Sardinian alcohol-preferring (msP) rats: an animal model to study the neurobiology of alcoholism. Addict Biol 11: 339–355.

Courtney KE, Polich J (2009). Binge drinking in young adults: data, definitions, and determinants. Psychol Bull 135: 142–156.

D'Anna KL, Stevenson SA, Gammie SC (2005). Urocortin 1 and 3 impair maternal defense behavior in mice. Behav Neurosci 119: 1061–1071.

Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Ross J, Hawkins J et al (2008). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ 57: 1–131.

Fahlke C, Hard E, Eriksson CJ, Engel JA, Hansen S (1995). Consequence of long-term exposure to corticosterone or dexamethasone on ethanol consumption in the adrenalectomized rat, and the effect of type I and type II corticosteroid receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 117: 216–224.

Fahlke C, Hard E, Hansen S (1996). Facilitation of ethanol consumption by intracerebroventricular infusions of corticosterone. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 127: 133–139.

Fahlke C, Hard E, Thomasson R, Engel JA, Hansen S (1994). Metyrapone-induced suppression of corticosterone synthesis reduces ethanol consumption in high-preferring rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 48: 977–981.

Finn DA, Snelling C, Fretwell AM, Tanchuck MA, Underwood L, Cole M et al (2007). Increased drinking during withdrawal from intermittent ethanol exposure is blocked by the CRF receptor antagonist d-Phe-CRF(12–41). Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31: 939–949.

Funk CK, O'Dell LE, Crawford EF, Koob GF (2006). Corticotropin-releasing factor within the central nucleus of the amygdala mediates enhanced ethanol self-administration in withdrawn, ethanol-dependent rats. J Neurosci 26: 11324–11332.

Goeders NE, Guerin GF (1996). Effects of surgical and pharmacological adrenalectomy on the initiation and maintenance of intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats. Brain Res 722: 145–152.

Goeders NE, Guerin GF (2008). Effects of the combination of metyrapone and oxazepam on cocaine and food self-administration in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 91: 181–189.

Gupta T, Syed YM, Revis AA, Miller SA, Martinez M, Cohn KA et al (2008). Acute effects of acamprosate and MPEP on ethanol drinking-in-the-dark in male C57BL/6J mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32: 1992–1998.

Hauger RL, Risbrough V, Brauns O, Dautzenberg FM (2006). Corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) receptor signaling in the central nervous system: new molecular targets. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 5: 453–479.

Heikinheimo O, Pesonen U, Huupponen R, Koulu M, Lahteenmaki P (1994). Hepatic metabolism and distribution of mifepristone and its metabolites in rats. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England) 9 (Suppl 1): 40–46.

Heilig M, Koob GF (2007). A key role for corticotropin-releasing factor in alcohol dependence. Trends Neurosci 30: 399–406.

Heinrichs SC, Koob GF (2004). Corticotropin-releasing factor in brain: a role in activation, arousal, and affect regulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 311: 427–440.

Heinrichs SC, Menzaghi F, Pich EM, Baldwin HA, Rassnick S, Britton KT et al (1994). Anti-stress action of a corticotropin-releasing factor antagonist on behavioral reactivity to stressors of varying type and intensity. Neuropsychopharmacology 11: 179–186.

Heinrichs SC, Richard D (1999). The role of corticotropin-releasing factor and urocortin in the modulation of ingestive behavior. Neuropeptides 33: 350–359.

Hendrickson LM, Zhao-Shea R, Tapper AR (2009). Modulation of ethanol drinking-in-the-dark by mecamylamine and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists in C57BL/6J mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 204: 563–572.

Imaki T, Naruse M, Harada S, Chikada N, Imaki J, Onodera H et al (1996). Corticotropin-releasing factor up-regulates its own receptor mRNA in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 38: 166–170.

Jennison KM (2004). The short-term effects and unintended long-term consequences of binge drinking in college: a 10-year follow-up study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 30: 659–684.

Ji D, Gilpin NW, Richardson HN, Rivier CL, Koob GF (2008). Effects of naltrexone, duloxetine, and a corticotropin-releasing factor type 1 receptor antagonist on binge-like alcohol drinking in rats. Behav Pharmacol 19: 1–12.

Jonas HA, Dobson AJ, Brown WJ (2000). Patterns of alcohol consumption in young Australian women: socio-demographic factors, health-related behaviours and physical health. Aust N Z J Public Health 24: 185–191.

Kamdar NK, Miller SA, Syed YM, Bhayana R, Gupta T, Rhodes JS (2007). Acute effects of naltrexone and GBR 12909 on ethanol drinking-in-the-dark in C57BL/6J mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 192: 207–217.

Kehne JH (2007). The CRF1 receptor, a novel target for the treatment of depression, anxiety, and stress-related disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 6: 163–182.

Keller C, Bruelisauer A, Lemaire M, Enz A (2002). Brain pharmacokinetics of a nonpeptidic corticotropin-releasing factor receptor antagonist. Drug Metab Dispos 30: 173–176.

Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS (2008). Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend 93: 21–29.

Koenig HN, Olive MF (2004). The glucocorticoid receptor antagonist mifepristone reduces ethanol intake in rats under limited access conditions. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29: 999–1003.

Koob G, Kreek MJ (2007). Stress, dysregulation of drug reward pathways, and the transition to drug dependence. Am J Psychiatry 164: 1149–1159.

Koob GF (2000). Animal models of craving for ethanol. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 95 (Suppl 2): S73–S81.

Koob GF (2003). Alcoholism: allostasis and beyond. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 27: 232–243.

Koob GF (2008). A role for brain stress systems in addiction. Neuron 59: 11–34.

Koob GF, Le Moal M (2008). Review. Neurobiological mechanisms for opponent motivational processes in addiction. Philos Trans R Soc Lond 363: 3113–3123.

Krishnan S, Nash Jr JF, Maickel RP (1991). Free-choice ethanol consumption by rats: effects of ACTH4-10. Alcohol (Fayetteville, NY) 8: 401–404.

Krugers HJ, Maslam S, Korf J, Joels M, Holsboer F (2000). The corticosterone synthesis inhibitor metyrapone prevents hypoxia/ischemia-induced loss of synaptic function in the rat hippocampus. Stroke 31: 1162–1172.

Kuperman Y, Chen A (2008). Urocortins: emerging metabolic and energy homeostasis perspectives. Trends Endocrinol Metab 19: 122–129.

Laborie C, Bernet F, Dutriez-Casteloot I, Lesage J, Dupouy JP (1997). Effect of cholinergic blockade on glucocorticoid regulation of NPY and catecholamines in the rat adrenal gland. Neuroendocrinology 66: 98–105.

Laborie C, Bernet F, Kerckaert JP, Maubert E, Lesage J, Dupouy JP (1995). Regulation of neuropeptide Y and its mRNA by glucocorticoids in the rat adrenal gland. Neuroendocrinology 62: 601–610.

Le AD, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Fletcher PJ, Shaham Y (2002). The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in the median raphe nucleus in relapse to alcohol. J Neurosci 22: 7844–7849.

Lee S, Rivier C (1997). An initial, three-day-long treatment with alcohol induces a long-lasting phenomenon of selective tolerance in the activity of the rat hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Neurosci 17: 8856–8866.

Ling PM, Neilands TB, Glantz SA (2009). Young adult smoking behavior: a national survey. Am J Prev Med 36: 389–394 e2.

Liu X, Weiss F (2002). Additive effect of stress and drug cues on reinstatement of ethanol seeking: exacerbation by history of dependence and role of concurrent activation of corticotropin-releasing factor and opioid mechanisms. J Neurosci 22: 7856–7861.

Lodge DJ, Lawrence AJ (2003). The CRF1 receptor antagonist antalarmin reduces volitional ethanol consumption in isolation-reared fawn-hooded rats. Neuroscience 117: 243–247.

Loh DH, Abad C, Colwell CS, Waschek JA (2008). Vasoactive intestinal peptide is critical for circadian regulation of glucocorticoids. Neuroendocrinology 88: 246–255.

Lowery EG, Sparrow AM, Breese GR, Knapp DJ, Thiele TE (2008). The CRF-1 receptor antagonist, CP-154,526, attenuates stress-induced increases in ethanol consumption by BALB/cJ mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32: 240–248.

Lyons AM, Lowery EG, Sparta DR, Thiele TE (2008). Effects of food availability and administration of orexigenic and anorectic agents on elevated ethanol drinking associated with drinking in the dark procedures. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32: 1962–1968.

Matsuzaki I, Takamatsu Y, Moroji T (1989). The effects of intracerebroventricularly injected corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) on the central nervous system: behavioural and biochemical studies. Neuropeptides 13: 147–155.

Menzaghi F, Rassnick S, Heinrichs S, Baldwin H, Pich EM, Weiss F et al (1994). The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in the anxiogenic effects of ethanol withdrawal. Ann N Y Acad Sci 739: 176–184.

Merlo Pich E, Lorang M, Yeganeh M, Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Raber J, Koob GF et al (1995). Increase of extracellular corticotropin-releasing factor-like immunoreactivity levels in the amygdala of awake rats during restraint stress and ethanol withdrawal as measured by microdialysis. J Neurosci 15: 5439–5447.

Morrow AL, Porcu P, Boyd KN, Grant KA (2006). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis modulation of GABAergic neuroactive steroids influences ethanol sensitivity and drinking behavior. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 8: 463–477.

Nair A, Bonneau RH (2006). Stress-induced elevation of glucocorticoids increases microglia proliferation through NMDA receptor activation. Journal of Neuroimmunology 171: 72–85.

National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism Advisory Council (2004). NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking. In NIAAA Newsletter, Vol. Winter.

Navarro M, Cubero I, Chen AS, Chen HY, Knapp DJ, Breese GR et al (2005). Effects of melanocortin receptor activation and blockade on ethanol intake: A possible role for the melanocortin-4 receptor. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29: 949–957.

Nelson DE, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Nelson HA (2009). State alcohol-use estimates among youth and adults, 1993–2005. Am J Prev Med 36: 218–224.

Nishikawa H, Hata T, Itoh E, Funakami Y (2004). A role for corticotropin-releasing factor in repeated cold stress-induced anxiety-like behavior during forced swimming and elevated plus-maze tests in mice. Biol Pharm Bull 27: 352–356.

O'Callaghan MJ, Croft AP, Jacquot C, Little HJ (2005). The hypothalamopituitary-adrenal axis and alcohol preference. Brain Res Bull 68: 171–178.

Ogilvie K, Lee S, Rivier C (1997). Effect of three different modes of alcohol administration on the activity of the rat hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 21: 467–476.

Olive MF, Koenig HN, Nannini MA, Hodge CW (2002). Elevated extracellular CRF levels in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis during ethanol withdrawal and reduction by subsequent ethanol intake. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 72: 213–220.

Overstreet DH, Knapp DJ, Breese GR (2007). Drug challenges reveal differences in mediation of stress facilitation of voluntary alcohol drinking and withdrawal-induced anxiety in alcohol-preferring P rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31: 1473–1481.

Peeters BW, Tonnaer JA, Groen MB, Broekkamp CL, van der Voort HA, Schoonen WG et al (2004). Glucocorticoid receptor antagonists: new tools to investigate disorders characterizedby cortisol hypersecretion. Stress (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 7: 233–241.

Piazza PV, Maccari S, Deminiere JM, Le Moal M, Mormede P, Simon H (1991). Corticosterone levels determine individual vulnerability to amphetamine self-administration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 2088–2092.

Pich EM, Lorang M, Yeganeh M, Rodriguez dF, Raber J, Koob GF et al (1995). Increase of extracellular corticotropin-releasing factor-like immunoreactivity levels in the amygdala of awake rats during restraint stress and ethanol withdrawal as measured by microdialysis. J Neurosci 15: 5439–5447.

Pioszak AA, Parker NR, Suino-Powell K, Xu HE (2008). Molecular recognition of corticotropin-releasing factor by its G-protein-coupled receptor CRFR1. J Biol Chem 283: 32900–32912.

Potter E, Sutton S, Donaldson C, Chen R, Perrin M, Lewis K et al (1994). Distribution of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor mRNA expression in the rat brain and pituitary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 8777–8781.

Rassnick S, Heinrichs SC, Britton KT, Koob GF (1993). Microinjection of a corticotropin-releasing factor antagonist into the central nucleus of the amygdala reverses anxiogenic-like effects of ethanol withdrawal. Brain Res 605: 25–32.

Rhodes JS, Best K, Belknap JK, Finn DA, Crabbe JC (2005). Evaluation of a simple model of ethanol drinking to intoxication in C57BL/6J mice. Physiol Behav 84: 53–63.

Rhodes JS, Ford MM, Yu CH, Brown LL, Finn DA, Garland Jr T et al (2007). Mouse inbred strain differences in ethanol drinking to intoxication. Genes Brain Behav 6: 1–18.

Richardson HN, Lee SY, O'Dell LE, Koob GF, Rivier CL (2008). Alcohol self-administration acutely stimulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, but alcohol dependence leads to a dampened neuroendocrine state. Eur J Neurosci 28: 1641–1653.

Rivier J, Rivier C, Vale W (1984). Synthetic competitive antagonists of corticotropin-releasing factor: effect on ACTH secretion in the rat. Science (New York, NY) 224: 889–891.

Roberts AJ, Lessov CN, Phillips TJ (1995). Critical role for glucocorticoid receptors in stress- and ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 275: 790–797.

Ryabinin AE, Bachtell RK, Heinrichs SC, Lee S, Rivier C, Olive MF et al (2002). The corticotropin-releasing factor/urocortin system and alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 26: 714–722.

Ryabinin AE, Weitemier AZ (2006). The urocortin 1 neurocircuit: ethanol-sensitivity and potential involvement in alcohol consumption. Brain Res Rev 52: 368–380.

Ryabinin AE, Yoneyama N, Tanchuck MA, Mark GP, Finn DA (2008). Urocortin 1 microinjection into the mouse lateral septum regulates the acquisition and expression of alcohol consumption. Neuroscience 151: 780–790.

Salling MC, Faccidomo S, Hodge CW (2008). Nonselective suppression of operant ethanol and sucrose self-administration by the mGluR7 positive allosteric modulator AMN082. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 91: 14–20.

Schulz DW, Mansbach RS, Sprouse J, Braselton JP, Collins J, Corman M et al (1996). CP-154,526: a potent and selective nonpeptide antagonist of corticotropin releasing factor receptors. PNAS 93: 10477–10482.

Seidenstadt RM, Eaton KE (1978). Adrenal and ovarian regulation of salt and sucrose consumption. Physiol Behav 21: 313–316.

Shaham Y, Funk D, Erb S, Brown TJ, Walker CD, Stewart J (1997). Corticotropin-releasing factor, but not corticosterone, is involved in stress-induced relapse to heroin-seeking in rats. J Neurosci 17: 2605–2614.

Smart D, Coppell A, Rossant C, Hall M, McKnight AT (1999). Characterisation using microphysiometry of CRF receptor pharmacology. Eur J Pharmacol 379: 229–235.

Smith SM, Vale WW (2006). The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 8: 383–395.

Sommer WH, Rimondini R, Hansson AC, Hipskind PA, Gehlert DR, Barr CS et al (2008). Upregulation of voluntary alcohol intake, behavioral sensitivity to stress, and amygdala Crhr1 expression following a history of dependence. Biol Psychiatry 63: 139–145.

Song C, Earley B, Leonard BE (1995). Behavioral, neurochemical, and immunological responses to CRF administration. Is CRF a mediator of stress? Ann N Y Acad Sci 771: 55–72.

Song C, Earley B, Leonard BE (1997). Effect of chronic pretreatment with the sigma ligand JO 1784 on CRF-induced changes in behaviour, neurotransmitter and immunological function in the rat. Neuropsychobiology 35: 200–204.

Sparta DR, Ferraro III FM, Fee JR, Knapp DJ, Breese GR, Thiele TE (2009). The alcohol deprivation effect in C57BL/6J mice is observed using operant self-administration procedures and is modulated by CRF-1 receptor signaling. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33: 31–42.

Sparta DR, Sparrow AM, Lowery EG, Fee JR, Knapp DJ, Thiele TE (2008). Blockade of the corticotropin releasing factor type 1 receptor attenuates elevated ethanol drinking associated with drinking in the dark procedures. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32: 259–265.

Sundell L, Salomaa V, Vartiainen E, Poikolainen K, Laatikainen T (2008). Increased stroke risk is related to a binge-drinking habit. Stroke 39: 3179–3184.

Szumlinski KK, Diab ME, Friedman R, Henze LM, Lominac KD, Bowers MS (2007). Accumbens neurochemical adaptations produced by binge-like alcohol consumption. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 190: 415–431.

Terawaki K, Koike K, Yuzurihara M, Kase Y, Takeda S, Aburada M et al (2004). Effects of the traditional Japanese medicine Unkei-to on the corticotropin-releasing factor-induced increase in locomotor activity. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 78: 799–803.

Toriola AT, Kurl S, Laukkanen JA, Kauhanen J (2009). Does binge drinking increase the risk of lung cancer: results from the Findrink study. Eur J Public Health 19: 389–393.

Treutlein J, Kissling C, Frank J, Wiemann S, Dong L, Depner M et al (2006). Genetic association of the human corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 1 (CRHR1) with binge drinking and alcohol intake patterns in two independent samples. Mol Psychiatry 11: 594–602.

Valdez GR, Koob GF (2004). Allostasis and dysregulation of corticotropin-releasing factor and neuropeptide Y systems: implications for the development of alcoholism. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 79: 671–689.

Valdez GR, Roberts AJ, Chan K, Davis H, Brennan M, Zorrilla EP et al (2002). Increased ethanol self-administration and anxiety-like behavior during acute ethanol withdrawal and protracted abstinence: regulation by corticotropin-releasing factor. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 26: 1494–1501.

Veldhuis HD, De Wied D (1984). Differential behavioral actions of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF). Pharmacol Biochem Behav 21: 707–713.

Venihaki M, Sakihara S, Subramanian S, Dikkes P, Weninger SC, Liapakis G et al (2004). Urocortin III, a brain neuropeptide of the corticotropin-releasing hormone family: modulation by stress and attenuation of some anxiety-like behaviours. J Neuroendocrinol 16: 411–422.

Yang X, Wang S, Rice KC, Munro CA, Wand GS (2008). Restraint stress and ethanol consumption in two mouse strains. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32: 840–852.

Zorrilla EP, Valdez GR, Weiss F (2001). Changes in levels of regional CRF-like-immunoreactivity and plasma corticosterone during protracted drug withdrawal in dependent rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 158: 374–381.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH Grants AA017803, A1AA013573, AA015148, AA014983, AA011605, and AA016629, and the Department of Defense Grants W81XWH-06-1-0158 and W81XWH-09-1-0293.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Emily Lowery, Marina Spanos, Angela Lyons, Dr Montserrat Thiele, Dr Clyde Hodge, and Dr Todd Thiele have each indicated that they do not have conflict of interest that influence this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lowery, E., Spanos, M., Navarro, M. et al. CRF-1 Antagonist and CRF-2 Agonist Decrease Binge-Like Ethanol Drinking in C57BL/6J Mice Independent of the HPA Axis. Neuropsychopharmacol 35, 1241–1252 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.209

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.209

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Further evidence for the involvement of the PPARγ system on alcohol intake and sensitivity in rodents

Psychopharmacology (2020)

-

Methanol extract of semen Ziziphi Spinosae attenuates ethanol withdrawal anxiety by improving neuropeptide signaling in the central amygdala

BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine (2019)

-

Endocannabinoid control of the insular-bed nucleus of the stria terminalis circuit regulates negative affective behavior associated with alcohol abstinence

Neuropsychopharmacology (2019)

-

Dynorphin-kappa opioid receptor activity in the central amygdala modulates binge-like alcohol drinking in mice

Neuropsychopharmacology (2019)

-

Persistent escalation of alcohol consumption by mice exposed to brief episodes of social defeat stress: suppression by CRF-R1 antagonism

Psychopharmacology (2018)