Abstract

Recent angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy measurements on strong spin–orbit coupled materials have shown an in-plane orbital-texture switch at their respective Dirac points, regardless of whether they are topological insulators or ‘trivial’ Rashba materials. This feature has also been demonstrated in a few materials (Bi2Se3, Bi2Te3 and BiTeI) though DFT calculations. Here we present a minimal orbital-derived tight binding model to calculate the electron wavefunction in a two-dimensional crystal lattice. We show that the orbital components of the wavefunction demonstrate an orbital-texture switch in addition to the usual spin switch seen in spin polarised bands. This orbital-texture switch is determined by the existence of three main properties: local or global inversion symmetry breaking, strong spin–orbit coupling and non-local physics (the electrons are on a lattice). Using our model, we demonstrate that the orbital-texture switch is ubiquitous and to be expected in many real systems. The orbital hybridisation of the bands is the key aspect for understanding the unique wavefunction properties of these materials, and this minimal model helps to establish the quantum perturbations that drive these hybridisations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In quantum systems, the key piece of information that describes the physics involved is the Hamiltonian and the wavefunctions of the system’s constituents.1–3 Typically, we are interested in the electron energies, momenta and spin states, i.e., the electronic band structure. However, with the recent interest in strongly spin–orbit coupled systems and topological materials, it is becoming clear that there is additional critical information, i.e., that pertaining to the orbital wavefunctions and symmetries, their relative phases and how they couple with the spin degrees of freedom of the material.

In three-dimensional topological insulators (TIs), the inversion of an odd number of bands per unit cell leads to the necessity of a topological surface state with Dirac-like dispersion, and a frequently described momentum-locked helical spin structure that is left-handed above the Dirac point and right-handed below.3,4 However, such a description ignores the fact that the J states and not the spin states are the relevant eigenstates of the spin–orbit coupled system, so there must be a richer manifold of entangled spin and orbital states than described in this simplistic picture. This was shown by detailed angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) experiments in a prototypical TI Bi2Se3.2,3,5,6 As part of this physics, different orbital states directly couple with specific spins.7 In the case of Bi2Se3, the different orbitals can couple with spins that do not follow the net helicity of the spin bands.1,2,5 This has ramifications when considering the bands as being entirely spin polarised, as in reality they are a superposition of opposing spins coupled with different orbitals.

A similar situation exists for Rashba states, in which the conventional picture is the spin–split parabolic band.8,9 In this picture, the electron wavefunction is simply the two split bands with the spin component pointing in opposing directions. The opposite spins couple with the magnetic field (or broken inversion symmetry at the surface) and raise or lower the electrons energy. More precisely, a recent work1,10 has shown a complicated orbital and spin texture that is highly reminiscent of that of the TIs. In particular, there are spins of both helicities in the inner and outer Rashba bands, and these spins may couple with orbitals of different types. Elucidating the origin and underlying symmetry requirements for the spin behaviour and especially the orbital-texture switch is the goal of the present paper.

In an earlier work,11 we used Density Functional Theory (DFT) to study the effects of spin–orbit-induced hybridisation in multi-band solids, including both TIs with band inversion as well as Rashba bulk solids. In that work, we showed quite generally that Spin Orbit Coupling (SOC)-induced hybridisation of different azimuthal orbital momenta leads to a truncation of the spin magnitude in each band below its maximal value of ±1, with different levels of spin truncation in different bands arising from different orbital textures in those bands. Distilling the minimal ingredients that drives such physics is, however, difficult to access from these DFT calculations.

Here we use an orbitally intuitive minimal model of Rashba states at the outset, both for solving the electronic structure problem and for explaining the crucial couplings responsible from the main effects, focusing especially on the crucial orbital-texture switch, which has been observed to occur exactly at the Dirac points.

We show that the orbital-texture switch is determined by the existence of three main properties: local or global inversion symmetry breaking, strong spin–orbit coupling and non-local physics (the electrons are on a lattice). Using our model, we demonstrate that the orbital-texture switch is ubiquitous and to be expected in many real systems. The orbital hybridisation of the bands is the key aspect for understanding the unique wavefunction properties of these materials, and this minimal model helps to establish the quantum perturbations that drive these hybridisations.

Results

The Hamiltonian of equation (6) has three main components: orbital hybridisation ω and δ, spin–orbit coupling α, and the out-of-plane symmetry-breaking field γ. Figure 1 shows the band solution to the model Hamiltonian with parameter choices , , and that are reasonable for a typical ‘strong’ spin–orbit compound on a hexagonal lattice. Six bands are observed, as equation (1) begins with a six-state basis. All bands, but especially the lowest pair of bands, exhibit a typical Rashba-like band structure corresponding to an ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ set of bands that are degenerate at Γ. All bands are made of a combination of various orbitals and spins, with the mixing ratios of the spins and orbitals determined when the Hamiltonian is diagonalised. The colouring of the bands in both Figure 1a,b indicate the orbital decomposition of the wavefunctions, including all three orbitals (Figure 1a) or the in-plane orbitals only (Figure 1b). The upper four bands have principally in-plane character (px, py or prad, ptan) at the gamma point (blue/green), whereas the lower two bands have principally out-of-plane character at the gamma point (pz or red). Ignoring minor splittings, these would nominally correspond to the J3/2 states (two upper branches) and the J1/2 states (lower branch), although from the diagrams it is clear that this nomenclature is only reasonable near the zone centre.

Band dispersion solution to the model Hamiltonian. (a) Band dispersion solution to the model Hamiltonian. The bands are coloured according to their orbital contribution, giving a (R, G, B) colour at each point corresponding to (pz, prad, ptan) contribution. Thus, a red point corresponds to pz dominated, whereas green and blue points correspond to radial and tangential p-orbital dominated, respectively. A teal colour would correspond to equal parts radial and tangential. (b) The same band structure with the red (pz) component turned off in the colouring. This shows the underlying orbital-texture switch in the lowest Rashba band pair. (c) The Bruillion zone and the two Rashba bands at the energy shown by the horizontal line in figure (b). In addition, the dominant in-plane orbital contribution is shown on each Rashba Band.

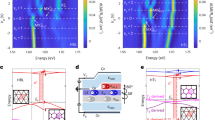

Figure 2 shows more details of the orbital and spin contributions of the lower pair of Rashba-split states near the zone centre, over the k-space range shown by the rectangular box in Figure 1b. The left panels of Figure 2 show the breakdown for the outer states (bold, Figure 2a) and the right panels show the breakdown for the inner states. It can be seen from Figure 2b that at gamma, the pz orbital (red) dominates the wavefunction of both inner and outer states, although this dominance quickly decays as one moves away from the gamma point. In addition, we can see that at gamma, the radial and tangential orbitals have a small and equal contribution to the wavefunction. As we move far away from gamma, the radial component quickly grows and the tangential and out-of-plane components decrease. In the inner bands, the tangential component initially raises in contribution, whereas the radial component initially decreases. This is the fundamental aspect of the orbital-texture switch in these Rashba bands—one band picks up a radial contribution, whereas the other picks up a tangential one. Next, as it applies to spin (Figure 2c), we can see that in the outer bands, both the out-of-plane and the radial components, have right-handed helicity, whereas the tangential component carries a left-handed spin. In the inner bands, the situation is reversed and the radial and out-of-plane components carry a left-handed spin, and the now stronger tangential bands carry a right-handed spin. An important aspect here is that the pz and radial states carry the same spin helicity, whereas the tangential states carry an opposite helicity, with all helicities switching when going from the inner to the outer Rashba band. This is identical to the situation discovered empirically for the Dirac state in the TIs Bi2Se3 and Bi2Te3,12 although here we show how it comes directly from a simplistic model.

Orbital and spin decomposition. (a) The band dispersion of the same lowest set of Rashba bands from Figure 1 (see dashed box in Figure 1b). Here we separate the inner and outer Rashba bands. On the left column the outer bands are highlighted, and the right column the inner bands are highlighted. (b) The orbital contribution of the bands. The red lines show the pz component, showing how they dominate at gamma point, and decrease in strength when moving away. The green shows the radial component, which has an overall trend of increasing while moving away from the gamma point. It, however, shows a distinct difference on the inner Rashba bands where the weight decreases to zero before increasing. The tangential component decreases in the outer bands, but increases in the inner bands when moving away from gamma. (c) The spin of these orbital contributions. Both the radial and out-of-plane p-orbitals have a right-handed spin on the outer band and a left-handed spin on the inner bands. The tangential p-orbitals have opposing spin helicity.

The superposition of these opposing helicities in these bands can create unique spin polarisations and reduce the overall net magnitude of spin measured in experiments. This has been an issue in many TI experiments, and we demonstrate here that this feature should be expected to be present in nearly all Rashba materials (even if the effect is small). For the case of carefully selecting the light’s electric fields to be in the plane of the material, it is possible to ignore the out-of-plane orbital in the photoemission process, and therefore measure the spin of purely these in-plane orbitals.2 These in-plane orbitals have spin components that oppose each other, giving rise to complete control over the photoelectron spin. By coming in with normal incidence light (E-field in the plane of the sample so selecting only in-plane orbital states), and changing the polarisation from linear horizontal, vertical, +sp, −sp, +circular and −circular, it should be possible to controllably and reproducibly eject photoelectrons with their spin along any arbitrarily chosen direction (x, y, z or anywhere in between). This as a technically feasibility has been demonstrated multiple times in recent ARPES measurements.6,7

Figure 3 compares another aspect of this Rashba simulation with calculations and experimental data from the prototypical three-dimensional TI, Bi2Se3. We can characterise the strength of the orbital polarisation through the orbital polarisation parameter λ, originally defined for the TIs Bi2Se3 and Bi2Te3 in ref. 2:

where I0 and I90 are the photoemission intensities along two orthogonal high-symmetry directions when using properly polarised incident photons, or equivalently, the projected orbital polarisations. Figure 3a shows the k-dependence of the λ term for the two lower bands, inner and outer, in the Rashba system calculated here, whereas Figure 3(b) shows the k-dependence of λ for the upper and lower Dirac cones in Bi2Se3 and Bi2Te3 calculated from DFT-projected intensities. Clearly, the trends of the two systems are extremely similar, with the main difference that the model Rashba system has a more marked in-plane orbital-texture switch (with magnitude approaching unity) than the TIs, which have maximum magnitude of ~0.5. In addition, we can simulate an expected ARPES spectrum of these Rashba bands. As expected, we see two concentric circles in k-space at a constant energy surface if we come in with p-polarisation (selecting out-of-plane orbitals). However, if we instead come in with a light polarisation in the plane of the material, we select the in-plane orbitals and see arcs of ARPES intensity that have opposing directions. The outer Rashba band shows arcs top-bottom, whereas the inner one shows arcs left-right. This can be compared directly with the measurement of Bi2Se3 reproduced in Figure 3d, which shows that the upper Dirac cone exhibits the left-right arc pattern, whereas the lower Dirac cone exhibits a top-bottom spectral intensity pattern.

Comparison with ARPES on Bi2Se3. (a) Orbital asymmetry parameter lambda as a function of crystal momentum away from the gamma point for the Rashba bands calculated here. The outer band has a positive lambda indicating predominantly radial character to the in-plane states, whereas the inner band is negative indicating predominant tangential in-plane character. (b) The same lambda plot calculated from first principals for the surface Dirac states of the topological insulators Bi2Se3 and Bi2Te3 (taken from ref. 2). The effect is very similar for the Rashba (a) and TI materials (b), although the magnitude of the effect (strength of lambda) is greater for the Rashba case. (c1) Simulated ARPES spectrum for p-polarised light on the Rashba bands, showing both inner and outer band at the same constant energy slice. (c2) Simulated ARPES spectrum for s-polarised light, highlighting the orbital-texture switch by showing the nodes in spectral weight changing from being along the kx=0 axis to the ky=0 axis when going from outer to inner band. (d) Experimental constant energy cuts of Bi2Se3 taken with s-polarised light, from ref. 2. Shown here is the same structure as seen in (c2), switching from left-right dominated at higher energies (inner bands) to top-bottom dominated at lower energies (outer bands).

Figure 4c,d shows cartoons that summarise our findings for both the nominal J1/2 Rashba bands (top) and surface Dirac bands from the TI compounds Bi2Se3 and Bi2Te3. It can be seen for both materials that the bands actually built out of a superposition of orbitals. Shown in the cartoon, they are composed of 90% out-of-plane p-orbitals with a 10% contribution of in-plane orbitals (coupled with their own spins). The out-of-plane orbitals couple with the traditional spin helicity expected in both Rashba and TI bands. Separately, the in-plane orbitals actually couple with spin in a unique manner, giving a right-handed spin texture to both the inner and outer Rashba bands (upper and lower Dirac cones). The orbitals themselves are also not uniquely radial or tangential, and in fact, switch their dominance at the gamma point in both materials. For the Rashba bands, the inner band is dominated by tangential p-orbitals close to the gamma point, whereas the outer band is dominated by radial orbitals.

Cartoon showing spin–orbital decomposition. Cartoon showing the band structure of the lower set of Rashba bands (upper panel) and surface Dirac bands in topological insulators (lower panel, reproduced from ref. 2). With a simple mapping of inner Rashba to upper Dirac cone, we observe a marked similarity in all aspects of the orbital and spin makeup of these bands. In particular, the pz orbitals (green—left panels) dominate these bands and have a left/right spin helicity upon crossing the degeneracy point. The weaker in-plane orbital components (right panels) have right-handed spin helicity on both sides of the degeneracy point and show an in-plane orbital-texture switch from predominantly tangential to predominantly radial.

Discussion

The inversion symmetry-breaking term γ expanded to first order in crystal momentum k shows a linear dependence near gamma. This term hybridises the in-plane and pz orbitals, breaking the usual assumption where the bands would not interact at all. This interaction term additionally can cause an avoided crossing in the band structure, where at the anti-crossing the two bands are strongly hybridised and demonstrate the most mixing.

When spin–orbit coupling is turned on, the degeneracy of the bands is lifted due to further mixing among each spin state. These spin states, however, are also coupled to orbital angular momentum, so the orbitals themselves must also mix. It is through this coupling that the bands can develop unique features such as orbital-texture switches centred around various high-symmetry points. The most striking of these is at the gamma point, where the orbital-texture switches from a radial to tangential texture, having direct consequence to experiments on the materials.

It is also possible to extend this model to non-two-dimensional materials as well. By further extending the model in the standard tight binding approach, it will be possible to calculate the orbital texture of bands in materials with more complicated atomic bases. These materials may show unique orbital textures for each atom type in the material, as the basis would be a summation of p-orbitals on each like-atom in the material. This will help further understand experiments that are sensitive to the depth of the material.

Here we presented a simple model with few restrictions: local or global inversion symmetry breaking, strong spin–orbit coupling and non-local physics (electrons on a lattice). This model shows the orbital-texture switch seen in ARPES studies.1,2,5 This model also predicts that this feature is not unique to these materials, and in fact should be present in all strong spin–orbit coupled materials with broken inversion symmetry. This would suggest that this feature is as ubiquitous as the classic spin splitting seen in spin–orbit coupled models. This feature is also not restricted to materials on a hexagonal lattice, and we predict orbital-texture switches to be present on square or rectangular lattice materials as well. Through this simple model, it is possible to understand the underlying physics of seemingly exotic experimental observations that happen in strong spin–orbit coupled materials.

Materials and methods

We shall model Rashba bands with a tight binding model of a two-dimensional sheet of hexagonal or square lattice atoms. Each site will have the atomic states px, py and pz orbitals centred on them, where the z axis is perpendicular to the plane of atoms. We chose to neglect s-orbitals because they have no angular momentum, therefore not contributing to spin–orbit coupling. The basis set chosen is that used by many other DFT projections in the field.5 As there is strong spin–orbit coupling, the basis set cannot be separated into spin and orbital components separately. The basis set must instead contain a full set of spins and orbitals assuming there is coupling of each orbital with any arbitrary spin. To account for this, the basis is

where pi are p-orbitals in the three Cartesian directions (i=x, y, z), and σz is the spin component in the out-of-plane direction.

We take the Hamiltonian from Peterson and Hedergard.9

Where

We then add spin–orbit coupling in the atomic basis form:

with

Where the basis set is

The γ term in the Hamiltonian allows for the hopping of an electron from an in-plane p-orbital to a neighbouring atom’s pz orbital, and in this simplest two-dimensional model will only be present if there is an out-of-plane distortion or field. In a bulk three-dimensional system, this will usually come from a surface term (the classic Rashba effect) though it can also come from an intrinsic symmetry-breaking field or distortion.8,13–15

This hopping shows up in the Hamiltonian as off-diagonal elements between in-plane and pz orbitals. These hopping elements of the Hamiltonian develop a momentum dependence, having no interaction at k=0 (gamma point). These terms mix the basis states further than just the off-diagonal SOC terms, which are k-independent.

This entire Hamiltonian has some symmetries by design. First is the crystal symmetry, chosen here as a hexagonal, rectangular or square lattice. This lattice allows for the electrons to hop, therefore bringing in a non-local momentum-dependence despite being built out of localised atomic orbitals. Next, there is out-of-plane inversion symmetry breaking, i.e., the γ terms. Last, there is spin–orbit coupling in the form explained previously. As we will show, it is with the combination of all three of these ingredients that we produce the unique orbital-texture switch observed in the experiments and the DFT calculations. Other interesting features of these states such as ‘backwards’ and/or ‘partial’ spin polarisation are also readily duplicated and understood using these simple terms.

References

Bawden, L. et al. Hierarchical spin-orbital polarization of a giant Rashba system. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500495 (2015).

Cao, Y. et al. Mapping the orbital wavefunction of the surface states in three-dimensional topological insulators. Nat. Phys. 9, 499–504 (2013).

Zhang, H., Liu, C.-X. & Zhang, S.-C. Spin-orbital texture in topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 066801 (2013).

Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Zhu, Z.-H. et al. Layer-by-layer entangled spin-orbital texture of the topological surface state in Bi2Se3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 216401 (2013).

Cao, Y. et al. Coupled spin-orbital texture in a prototypical topological insulator. Preprint at http://arXiv:1211.5998 (2012).

Zhu, Z.-H. et al. Photoelectron spin-polarization control in the topological insulator Bi2Se3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 076802 (2014).

Rashba, E. Properties of semiconductors with an extremum loop. 1. Cyclotron and combinational resonance in a magnetic field perpendicular to the plane of the loop. Sov. Phys. Solid State 2, 1109–1122 (1960).

Petersen, L. & Hedegård, P. A simple tight-binding model of spin-orbit splitting of sp-derived surface states. Surf. Sci. 459, 49–56 (2000).

Park, S. R., Kim, C. H., Yu, J., Han, J. H. & Kim, C. Orbital-angular-momentum based origin of Rashba-type surface band splitting. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 156803 (2011).

Liu, Q., Waugh, X. Z. J., Dessau, D. & Zunger, A. Orbital mapping of energy bands and the truncated spin polarization in three-dimensional Rashba semiconductors. Preprint at http://arXiv:1607.01692 (2016).

Mizuguchi, Y. et al. Superconductivity in novel BiS2-based layered superconductor LaO1-xFxBiS2 . J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 81, 114725 (2012).

Dresselhaus, G. Spin-orbit coupling effects in zinc blende structures. Phys. Rev. 100, 580–586 (1955).

Riley, J. et al. Direct observation of spin-polarized bulk bands in an inversion-symmetric semiconductor. Nat. Phys. 10, 835–839 (2014).

Zhang, X., Liu, Q., Luo, J.-W., Freeman, A. J. & Zunger, A. Hidden spin polarization in inversion-symmetric bulk crystals. Nat. Phys. 10, 387–393 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NSF DMREF project DMR-1334170 to the University of Colorado and the University of Kentucky. The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the US Department of Energy under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Waugh, J., Nummy, T., Parham, S. et al. Minimal ingredients for orbital-texture switches at Dirac points in strong spin–orbit coupled materials. npj Quant Mater 1, 16025 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/npjquantmats.2016.25

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npjquantmats.2016.25

This article is cited by

-

Hidden orbital polarization in diamond, silicon, germanium, gallium arsenide and layered materials

NPG Asia Materials (2017)