Abstract

Measurement-based quantum computation (MQC) is a paradigm for studying quantum computation using many-body entanglement and single-qubit measurements. Although MQC has inspired wide-ranging discoveries throughout quantum information, our understanding of the general principles underlying MQC seems to be biased by its historical reliance upon the archetypal 2D cluster state. Here we utilise recent advances in the subject of symmetry-protected topological order (SPTO) to introduce a novel MQC resource state, whose physical and computational behaviour differs fundamentally from that of the cluster state. We show that, in sharp contrast to the cluster state, our state enables universal quantum computation using only measurements of single-qubit Pauli X, Y, and Z operators. This novel computational feature is related to the ‘genuine’ 2D SPTO possessed by our state, and which is absent in the cluster state. Our concrete connection between the latent computational complexity of many-body systems and macroscopic quantum orders may find applications in quantum many-body simulation for benchmarking classically intractable complexity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The idea of measurement-based quantum computation (MQC), where computation is carried out solely through single-qubit measurements on a fixed many-body resource state and classical feed-forward of measurement outcomes,1–3 is quite surprising. This is because it highlights the origins of quantum advantage in terms of entanglement and non-commutative measurements, uniquely quantum effects without counterparts in classical mechanics. In particular, so-called universal resource states, the states that are capable of efficiently implementing universal MQC, represent a class of maximal entanglement in the classification of many-body entanglement,4 so that the structure and complexity of their entanglement is of great interest for advancing the understanding of quantum computation. Following the canonical example of the two-dimensional (2D) cluster state,5 many other universal resource states have been found, including cluster states defined on various lattices,4 some tensor network states,4,6–10 and model ground states in condensed matter physics such as 2D Affleck-Kennedy-Lieb-Tasaki (AKLT) states.10–15

Given the existence of these various known universal resource states, a natural question is whether we might be able to find any common key feature, so as to explore more their variety in fundamental structures as well as in practical applications. Although the earliest resource states for MQC were found in short-range correlated states described as somewhat artificial tensor network states,4,6–10 a new insight has been that a class of short-ranged entangled states structured by symmetry, endowed with so-called symmetry-protected topological order (SPTO),16–24 make excellent candidate resource states systematically. Indeed, in the setting of 1D spin chains, the ground states of several SPTO phases have already been shown to possess entanglement that can be leveraged to achieve various quantum computational tasks.25–31

Here, in adopting the concept of SPTO, we carry out such an investigation for the first time in 2D MQC, and discover a completely new kind of MQC universal resource state. Specifically, we first examine the 2D cluster state as well as a wide range of other universal resource states, and show that their 2D SPTO is trivial, of the same nature as that of unentangled product states. Looking more closely, we find that these previously known resource states do possess some ‘weaker’ SPTO, but essentially of a type closer to that of 1D spin chains. Our discovery is made possible owing to the recent progress of research into SPTO, which has revealed a hierarchy of SPTO as representing different levels of nonlocality of quantum information (see the next section for details). We then introduce our ‘Union Jack’ state, which in contrast possesses SPTO entirely of a 2D nature, and demonstrate that it is not only a universal resource state but additionally is ‘Pauli universal,’ in that it can implement arbitrary quantum computation using only single-qubit measurements in the Pauli bases. As elaborated later, this feature is forbidden in the 2D cluster state on account of the Gottesman-Knill theorem,32 which proves the efficient classical simulability of certain quantum gates. We will conclude with the outlook that our proof of principle result about Pauli universality may be true for more general 2D SPTO resource states, which we connect to a possible deep connection between a hierarchy of SPTO in condensed matter physics and the so-called Clifford hierarchy of quantum computation.

Results

Measurement-based quantum computation and the Clifford hierarchy

MQC is a means of utilising an entangled resource state to perform computation using (generally adaptive) single-qubit measurements. Given a particular resource state, we specify our computational process by choosing a specific pattern of single-qubit measurements. Owing to the probabilistic nature of measurement, different measurement outcomes will generally implement different computations. However, rather than attempting to correct for unintended measurement outcomes at every step, we can instead represent the effect of such outcomes as the product of our intended operation with a so-called byproduct operator. When these byproduct operators are sufficiently simple (e.g., Pauli operators), we can commute them through much of our computation, allowing disjoint measurements to be performed in parallel without adaptation of our measurement settings.

The canonical MQC resource state is the 2D cluster state,5 which is a universal resource state, in which arbitrary quantum circuits can be simulated efficiently using an appropriate sequence of arbitrary single-spin measurements.1–3 The 2D cluster state is formed by preparing qubit states on the vertices of a square lattice (with open boundary conditions), and applying entangling controlled-Z (CZ) operations, defined in the computational basis by , between nearest-neighbour qubits. It is described by stabiliser generators,

where neigh (i) is the set of nearest neighbours of site i. An n-qubit cluster state is the unique state satisfying for i=1, 2, …, n.

The Clifford hierarchy is an ordered collection of unitary gates of increasing computational generality.33 The unitary gates in the d’th level of the Clifford hierarchy are defined inductively, with consisting of tensor products of Pauli operators, and . Each level of the Clifford hierarchy represents a greater degree of quantum gate complexity in which, intuitively speaking, higher levels contain gates that are more ‘quantum’ than those in lower levels. The gates in form a group, known as the Clifford group, that preserves the group of Pauli operators under conjugation. Exploiting this fact, the Gottesman–Knill theorem32 gives an efficient means of classically simulating any poly-sized circuit composed of gates in , provided that initialisation and measurement occur in the single-qubit Pauli bases. By contrast, the gates in form a universal gate set for quantum computation.

In MQC, a stronger notion of universality for resource states is Pauli universality, where the measurements used to carry out MQC are only of single-qubit Pauli operators X, Y or Z. Although the 2D cluster state is a universal resource state, it is formed from CZ gates in and therefore can be efficiently classically simulated when only Pauli measurements are used, making the cluster state not Pauli universal.

Symmetry-protected topological order

Symmetry-protected topological order (SPTO)16–24 is a many-body phenomenon arising from many-body entanglement present in quantum states invariant under a symmetry group G. Given a state defined in d spatial dimensions with a finite correlation length, we say that this state has nontrivial d-dimensional SPTO precisely when it cannot be reduced to a product state using a finite-depth quantum circuit whose gates are of constant size and commute with G. In this sense, nontrivial SPTO can be thought of as an indicator of persistent entanglement, protected by G. More generally, two d-dimensional states are said to be in different (d-dimensional) SPTO phases when they cannot be transformed into each other using such a finite-depth, symmetry-respecting quantum circuit.

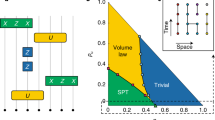

Mathematically, d-dimensional SPTO phases are classified by elements of , the (d+1)’th cohomology group of G, with the identity element of the group corresponding to the trivial phase of G-invariant product states (see the Supplementary Information Section A for an introduction to group cohomology theory). For example, when there is only one (trivial) 1D SPTO phase, but there are two 2D SPTO phases, one trivial and one nontrivial. Nontrivial SPTO can be detected and characterised by examining the manner in which G acts on edge degrees of freedom when a state is prepared on a manifold with boundaries.34–37 Nontrivial 1D SPTO manifests as a product of individual ‘fractionalised’ degrees of freedom on the edge, which transform under projective representations of G. On the other hand, nontrivial 2D SPTO manifests in the form of long-range correlated edge modes, which transform under non-separable matrix product unitary representations of G.34 Concrete examples of this distinctive behaviour of 1D and 2D SPTO are shown in Figure 1.

Manifestation of 1D and 2D SPTO in boundary symmetry operators, where X, Y, Z and CZ represent the application of the corresponding unitary operation. The transversal application of X is only a symmetry when each state is prepared on closed boundaries. Near edges of the system, the symmetry operator must be augmented with additional boundary terms that reflect the distinct nature of 1D versus 2D SPTO. (a) The cluster state is invariant under the application of X to all sites within a region with closed boundaries. When X is instead applied to a region with open boundaries (boxed area), we must add additional Z (and hence Y, whenever X and Z overlap) gates near the edges to obtain a genuine symmetry. (b) The Union Jack state is invariant under the application of X to a region with closed boundaries. When X is instead applied to a region with open boundaries (boxed area), we must add additional CZ gates near the edges to obtain a genuine symmetry. The higher-dimensional SPTO manifests here as a symmetry representation which does not factorise into disjoint unitaries, and is built from gates at a higher level of the Clifford hierarchy.

An important—and often neglected—fact is that states in d spatial dimensions can be classified not only by a label specifying its d-dimensional SPTO phase but also by other labels associated with k-dimensional SPTO, for 0≤k<d.18 We call this collection of SPTO labels the SPTO signature of a state, denoted by Ωd in d dimensions. For d=2, Ω2 has the form , with Θk denoting a k-dimensional SPTO label. For general d, Ωd contains k-dimensional SPTO labels, corresponding to the independent k-dimensional surfaces in d-dimensional space. When classifying phases, the Θk labels are chosen from , the collection of k-dimensional SPTO phases for symmetry G. However, as we are concerned here mainly with the existence of nontrivial SPTO, we will use an abbreviated notation where Θk=0 or 1 indicates trivial or nontrivial k-dimensional SPTO, respectively. Unlike d-dimensional labels, the lower-dimensional components of a state’s SPTO signature can be altered by a local G-symmetric quantum circuit. However, these labels are unchanged by quantum circuits that respect both on-site and lattice translational symmetries. See the Supplementary Information Section A for details about SPTO signatures.

Trivial 2D SPTO of the 2D cluster state

In this section, we determine the SPTO signature of the 2D cluster state, stated in Theorem 1.

Theorem 1. The SPTO signature of the 2D cluster state with respect to on-site symmetry is , corresponding to trivial 2D SPTO and nontrivial 1D SPTO.

The on-site symmetry of the cluster state comes from treating a 2×2 unit cell as a single site, as shown in Figure 2a. We refer to the four qubits within a unit cell by the labels NW, NE, SE and SW. From Equation (1) , we see that the global application of X to any of these four classes of qubits preserves the cluster state stabilisers, giving the system on-site symmetry. This is the largest on-site symmetry group of the cluster state, and its SPTO phase with respect to this group sets its SPTO phase with respect to any on-site symmetry subgroup. We do not discuss SPTO of the 2D cluster state with respect to time reversal, inversion, or lattice rotations, as these symmetries would not alter Theorem 1.

(a) Part of the 2D cluster state on a square lattice, with 2×2 unit cells shown. The four generators of the on-site symmetry are labelled. (b) Part of the circuit which disentangles the 2D cluster state. Solid lines indicate a CZ applied between two sites. The gate VE is shown in centre, which is the product of 6 CZ operations between sites (4, 8), (8, 12), (12, 14), (14, 10), (10, 6) and (6, 4). Also shown are portions of the VE gates directly above and below. Because of the ‘diagonal’ CZ’s of adjacent VE’s cancelling, a global tiling of these gates applies CZ between all adjacent NE and SE sites. This tiling is done in two layers, so that the gates in each layer do not overlap. By applying displaced and rotated versions of these gates, we arrive at a symmetry-respecting circuit of depth 8, which disentangles the 2D cluster state to a trivial product state.

We prove the 2D part of Theorem 1 by constructing a finite-depth quantum circuit, shown in Figure 2b, whose gates each respect the on-site symmetry of the cluster state, but which disentangles the state to a trivial product state. As the 2D component of a state’s SPTO signature is invariant under local symmetric quantum circuits,18 this suffices to prove our claim. A more careful analysis of the 2D cluster state is needed in order to prove its nontrivial 1D SPTO. In the Supplementary Information Section C, we study a projected entangled pair state (PEPS)38 representation of the cluster state, which lets us characterise the transformation of its boundary under the symmetry.37 We find that individual sites along both horizontal and vertical boundaries transform under a projective representation of , giving us a ‘smoking gun’ indication of nontrivial 1D SPTO. This fact, demonstrated rigorously in the Supplementary Information Section C, completes our proof of Theorem 1.

Importantly, a similar analysis of edge modes can be used to prove results analogous to Theorem 1 for many other known universal resource states, including cluster states defined on various lattices4 and certain 2D AKLT states.10–15 In this sense, the impact of Theorem 1 is that not just the cluster state, but in fact the majority of commonly studied universal resource states, are characterised by the absence of 2D SPTO, with at most nontrivial 1D SPTO.

The resource state with nontrivial 2D SPTO

In this section, we present a new MQC resource state that is both Pauli universal and possesses nontrivial 2D SPTO, as summarised in Theorem 2. This is in contrast to the 2D cluster state, which is universal but not Pauli universal, and only possesses 1D SPTO. Our ‘Union Jack’ resource state is composed of qubits, each of which is located at a vertex of the Union Jack lattice shown in Figure 3a. It is constructed by preparing a state at every vertex, and then applying a three-body doubly controlled-Z unitary operation, CCZ, to every triangular cell in the lattice. CCZ is diagonal in the qubits’ computational basis with non-zero matrix elements

and belongs to the 3rd level of the Clifford hierarchy . The stabilisers generated by these gates are

where (j, k)∈tri (i) refers to all pairs of sites (j, k) that, together with i, form a triangle in the lattice of Figure 3a. Our resource state is the unique state satisfying for i=1, 2, …, n. Note, however, that it is not a so-called stabiliser state because its stabiliser group is not contained in the n-qubit Pauli group.

(a) The Union Jack lattice on which our resource state is defined. Every vertex represents a qubit initialised in a state, and every triangular cell represents an applied three-body unitary CCZ. A 2×2 unit cell is shown, with respect to which our system has symmetry generated by X applied to sites a,b or c. The symmetry of this state is a subgroup of generated by applying X to all sites. (b) Measuring the control sites (red) in the computational basis collapses the remaining system into a random graph state. The edges of the graph lie on the ‘domain walls’ between different control site outcomes.

Our resource state is an example of a ‘renormalisation group fixed point’ state used previously to study properties of SPTO,18 and consequently has symmetry. However, if we redefine a single site of our system to be a particular 2×2 unit cell (shown in Figure 3a), then our system in fact has symmetry. With respect to this latter group, our resource state can be seen as an example of a d=2 decorated domain wall state,39 a method for creating systems with d-dimensional SPTO in terms of systems with (d−1)-dimensional G SPTO (here ). We should, however, emphasise the importance of our state being defined on the Union Jack lattice for proving Theorem 2, as the 2D state in refs 18,39 is essentially defined on a triangular lattice, so that it disallows the intersection of domain walls under the procedure we use below for locally converting to a graph state,40,41 and thus may not be a universal resource state. On the other hand, our state is also an example of a generalisation of graph states, called hypergraph states in the quantum information community,42,43 although their application for MQC has not been studied previously.

Theorem 2. The Union Jack state is a Pauli universal resource state for MQC, meaning that arbitrary quantum circuits can be efficiently simulated using only measurements of single-qubit Pauli operators and feed-forward of measurement outcomes. Furthermore, its SPTO signature with respect to on-site symmetry is , corresponding to nontrivial 2D SPTO and trivial 1D SPTO.

Note that although we phrase Theorem 2 in terms of our state’s SPTO for generality, the same statement holds true if we replace with . Here we demonstrate the Pauli universality of our state by efficiently simulating quantum circuits composed of Hadamard (H) and Toffoli (TOFF) gates—a universal set of gates for quantum computation44—using only measurements of single-qubit Pauli operators. Our means of simulating these circuits using the Union Jack state are divided into two parts. We first show that portions of our state can be converted into ‘cluster regions’, regions that are locally identical to the 2D cluster state. These cluster regions are used to prepare and readout qubit states, teleport these states over arbitrarily long distances, and apply Clifford gates (which include H gates) to them, all with the use of only Pauli measurements. We then demonstrate that we can implement CCZ using certain ‘interaction gadgets’, which are prepared using Pauli measurements. As we can implement both H and CCZ gates, and because TOFF and CCZ are related by TOFF(123)=H(3)CCZ(123)H(3), the combination of cluster regions and interaction gadgets lets us implement H and TOFF gates, and therefore arbitrary quantum circuits.

Our technique for creating cluster regions within the Union Jack state is to induce a symmetry-breaking phase transition from 2D to 1D SPTO. This involves first performing a computational basis measurement of all the Union Jack control qubits, shown in Figure 3b. This symmetry-breaking measurement forces the remaining part of our system, which lives on a regular square lattice, into a random graph state whose edges (associated with nontrivial 1D SPTO) appear along the domain walls in our measurement outcomes. In particular, we obtain an edge (CZ gate) in our graph whenever two adjacent measurement outcomes differ, and no edge whenever they agree. We can then use the exact same protocol as in ref. 45 to reduce this random graph state to a state that is locally identical to the regular 2D cluster state. This protocol succeeds with a probability that converges exponentially fast to either 0 or 1 in the limit of large cluster regions, depending on whether our random graph state percolates and has a macroscopic spanning cluster of connected vertices. We perform numerical simulations of this percolation problem for different system sizes, and conclude (Figure 4) that our Union Jack system is in a supercritical percolation phase and thus can be used to efficiently prepare connected cluster regions.

A simulation of our percolation problem with increasing linear size, L. The exponential decay of the non-spanning probability is characteristic of the percolation supercritical phase, demonstrating that portions of our Union Jack state can be locally reduced to a 2D cluster state with arbitrarily high probability. These cluster regions are used to perform Clifford operations upon our computational qubits, as well as to shuttle these qubits between spatially separated interaction gadgets, which can be connected together to produce logical CCZ gates.

Our technique for preparing interaction gadgets involves taking a small area of the Union Jack state and applying an appropriate pattern of Pauli measurements to it (Figure 5a). When embedded within a cluster region, these gadgets implement a three-body non-Clifford logical gate UI, defined by , where acts as Using UI, we can obtain CCZ by applying UI three times to the same triple of qubits, but with the qubits cyclically permuted each time. This permutation involves crossing adjacent wires, something that is forbidden in a strictly planar graph structure, but we can simulate a nonplanar wire crossing using a SWAP operation within our cluster regions (Figure 5b). The identity shows that this gives the desired operation of CCZ, up to byproduct CZ gates. These byproduct gates, as well as other byproduct Clifford gates that appear in our protocol, are adaptively eliminated within cluster regions by applying the appropriate inverse Clifford operations. This adaptive cancellation of byproduct operators is generally necessary before the application of subsequent H or CCZ logical gates, as attempting to commute them through these gates would lead to a byproduct group which does not close at any level of the Clifford hierarchy. Additional information about our protocol for establishing Pauli universality of the Union Jack state is given in the Supplementary Information Section D.

(a) Our ‘interaction gadget’ implements the non-Clifford operation UI, and is formed by measuring X and Z on seven logical sites, Y on one control site, and Z on the surrounding control sites. Postselection on 13 of the latter Z measurement outcomes is required in order for us to connect our gadget to the surrounding cluster region; however, this only introduces a constant overhead to the number of sites measured in our protocol, as shown in the Supplementary Information Section D. (b) A gadget for implementing SWAP within a cluster region. This allows us to implement nonplanar wire crossings that are necessary for simulating arbitrary circuits composed of H and TOFF gates. (c) A protocol for implementing a logical CCZ gate, where solid lines indicate teleportation of logical qubits. The majority of the sites involved have been converted to an extended cluster region, with the exception of the sites used to construct interaction gadgets. Our diagram only reflects the topology of the relevant logical connections, whereas a realistic implementation would involve a detailed measurement pattern to perform teleportation throughout the cluster region, as well as a significantly greater distance between neighbouring gadgets. More explicit details of our protocol can be found in the Supplementary Information Section D.

Looking at the proof just given, we see that the disparity between the universality of the cluster state and the Pauli universality of the Union Jack state arises from the difference in gates implementable by each state under Pauli measurements, for the former and for the latter. Some insight can be gained by comparing this computational difference to the fact that the cluster state and Union Jack state, respectively, possess 1D and 2D SPTO, as summarised in Table 1. Generalising from these examples, we might expect this correspondence between SPTO and the Clifford hierarchy to extend to a wider class of SPTO states, providing a general link between types of SPTO and degrees of quantum gate complexity. Such a correspondence was demonstrated in refs 46,47 for topological quantum-error-correcting codes, but proving this in the setting of MQC would give a means of directly associating computational characteristics to SPTO states, without the need for an auxiliary higher-dimensional topologically ordered system.

Discussion

Although pertaining most immediately to MQC, our main results can be fruitfully interpreted as general statements about the interplay of two intrinsically quantum ingredients, entanglement and measurement, which have a leading role in quantum information science. Our Theorem 1 demonstrates that previously studied resource states, despite differing in their microscopic details, possess identical forms of macroscopic entanglement, namely 1D SPTO. Although such entanglement is sufficient for universal quantum computation using arbitrary single-qubit measurements, our Theorem 2 demonstrates that the use of more complex forms of entanglement, namely 2D SPTO, lets us achieve the same results using simpler Pauli measurements. As argued in the previous section, we expect that this tradeoff between entanglement and measurement is not only true of more general quantum systems, but in fact is evidence of a deep connection between the hierarchies of SPTO and the Clifford hierarchy of quantum computation. Such a connection between the computational complexity of many-body systems and their emergent macroscopic behaviour would give a means of converting canonical condensed matter tools, such as order parameters, into interesting indicators of computational behaviour, as was done with 1D spin chains in ref. 30. The natural connection we demonstrate between the computational complexity of many-body systems and emergent macroscopic order may find applications for better understanding the emergence of classically intractable complexity within quantum many-body simulation.48,49

Methods

Additional information regarding SPTO and the proofs of our Theorems 1 and 2 can be found in the Supplementary Information.

References

Raussendorf, R. & Briegel, H. J. A one-way quantum computer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5188 (2001).

Raussendorf, R., Browne, D. E. & Briegel, H. J. Measurement-based quantum computation on cluster states. Phys. Rev. A 68, 022312 (2003).

Jozsa, R. An introduction to measurement based quantum computation. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0508124 (2005).

Van den Nest, M., Miyake, A., Dür, W. & Briegel, H. J. Universal resources for measurement-based quantum computation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 150504 (2006).

Briegel, H. J. & Raussendorf, R. Persistent entanglement in arrays of interacting particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 910 (2001).

Verstraete, F. & Cirac, J. I. Valence-bond states for quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 70, 060302 (R), (2004).

Gross, D. & Eisert, J. Novel schemes for measurement-based quantum computation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 220503 (2007).

Gross, D., Eisert, J., Schuch, N. & Perez-Garcia, D. Measurement-based quantum computation beyond the one-way model. Phys. Rev. A 76, 052315 (2007).

Chen, X., Zeng, B., Gu, Z.-C., Yoshida, B. & Chuang, I. L. Gapped two-body hamiltonian whose unique ground state is universal for one-way quantum computation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 220501 (2009).

Cai, J.-M., Miyake, A., Dür, W. & Briegel, H. J. Universal quantum computer from a quantum magnet. Phys. Rev. A 82, 052309 (2010).

Miyake, A. Quantum computational capability of a 2D valence bond solid phase. Ann. Phys 326, 1656 (2011).

Wei, T.-C., Affleck, I. & Raussendorf, R. Affleck-Kennedy-Lieb-Tasaki state on a honeycomb lattice is a universal quantum computational resource. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 070501 (2011).

Darmawan, A. S., Brennen, G. K. & Bartlett, S. D. Measurement-based quantum computation in a 2D phase of matter. New J. Phys. 14, 013023 (2012).

Wei, T.-C. Quantum computational universality of Affleck-Kennedy-Lieb-Tasaki states beyond the honeycomb lattice. Phys. Rev. A 88, 062307 (2013).

Wei, T.-C. & Raussendorf, R. Universal measurement-based quantum computation with spin-2 Affleck-Kennedy-Lieb-Tasaki states. Phys. Rev. A 92, 012310 (2015).

Gu, Z.-C. & Wen, X.-G. Tensor-entanglement-filtering renormalization approach and symmetry-protected topological order. Phys. Rev. B 80, 155131 (2009).

Chen, X., Gu, Z.-C., Liu, Z.-X. & Wen, X.-G. Symmetry protected topological orders in interacting bosonic systems. Science 338, 1604 (2012).

Chen, X., Gu, Z.-C., Liu, Z.-X. & Wen, X.-G. Symmetry protected topological orders and the group cohomology of their symmetry group. Phys. Rev. B 87, 155114 (2013).

Kitaev, A. Periodic table for topological insulators and superconductors. AIP Conf. Proc 1134, 22 (2009).

Ryu, S., Schnyder, A. P., Furusaki, A. & Ludwig, A. W. Topological insulators and superconductors: ten-fold way and dimensional hierarchy. New J. Phys. 12, 065010 (2010).

Pollmann, F., Berg, E., Turner, A. M. & Oshikawa, M. Symmetry protection of topological phases in one-dimensional quantum spin systems. Phys. Rev. B 85, 075125 (2012).

Chen, X., Gu, Z.-C. & Wen, X.-G. Classification of gapped symmetric phases in one-dimensional spin systems. Phys. Rev. B 83, 035107 (2011).

Schuch, N., Pérez-García, D. & Cirac, J. I. Classifying quantum phases using matrix product states and projected entangled pair states. Phys. Rev. B 84, 165139 (2011).

Pollmann, F., Turner, A. M., Berg, E. & Oshikawa, M. Entanglement spectrum of a topological phase in one dimension. Phys. Rev. B 81, 064439 (2010).

Brennen, G. K. & Miyake, A. Measurement-based quantum computer in the gapped ground state of a two-body Hamiltonian. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 010502 (2008).

Miyake, A. Quantum computation on the edge of a symmetry-protected topological order. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 040501 (2010).

Bartlett, S. D., Brennen, G. K., Miyake, A. & Renes, J. M. Quantum computational renormalization in the Haldane phase. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 110502 (2010).

Else, D. V., Schwarz, I., Bartlett, S. D. & Doherty, A. C. Symmetry-Protected phases for measurement-based quantum computation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 240505 (2012).

Else, D. V., Bartlett, S. D. & Doherty, A. C. Symmetry protection of measurement-based quantum computation in ground states. New J. Phys. 14, 113016 (2012).

Miller, J. & Miyake, A. Resource quality of a symmetry-protected topologically ordered phase for quantum computation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 120506 (2015).

Prakash, A. & Wei, T.-C. Ground states of one-dimensional symmetry-protected topological phases and their utility as resource states for quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 92, 022310 (2015).

Gottesman, D. The Heisenberg Representation of Quantum Computers. talk at International Conference on Group Theoretic Methods in Physics. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9807006. (1998).

Gottesman, D. & Chuang, I. L. Demonstrating the Viability of universal quantum computation using teleportation and single-qubit operations. Nature 402, 390 (1999).

Chen, X., Liu, Z.-X. & Wen, X.-G. Two-dimensional symmetry-protected topological orders and their protected gapless edge excitations. Phys. Rev. B 84, 235141 (2011).

Pollmann, F. & Turner, A. M. Detection of symmetry-protected topological phases in one dimension. Phys. Rev. B 86, 125441 (2012).

Else, D. V. & Nayak, C. Classifying symmetry-protected topological phases through the anomalous action of the symmetry on the edge. Phys. Rev. B 90, 235137 (2014).

Williamson, D. J. et al. Matrix Product Operators for Symmetry-Protected Topological Phases. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.5604 (2014).

Verstraete, F., Cirac, J. I. & Murg, V. Matrix product states, projected entangled pair states, and variational renormalization group methods for quantum spin systems. Adv. Phys 57, 143 (2008).

Chen, X., Lu, Y.-M. & Vishwanath, A. Symmetry-protected topological phases from decorated domain walls. Nat. Commun. 5, 3507 (2014).

Hein, M., Eisert, J. & Briegel, H. J. Multiparty entanglement in graph states. Phys. Rev. A 69, 062311 (2004).

Hein, M. et al. in Quantum Computers, Algorithms and Chaos Vol. 162, (eds Casati, G. et al.) 115–218 (IOS Press, 2006). Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0602096

Rossi, M., Huber, M., Bruß, D. & Macchiavello, C. Quantum hypergraph states. New J. Phys. 15, 113022 (2013).

Gühne, O. et al. Entanglement and nonclassical properties of hypergraph states. J. Phys. A 47, 335303 (2014).

Shi, Y.-Y. Both Toffoli and Controlled-not need little help to do universal quantum computation. Quant. Inform. Comput. 3, 84 (2003).

Browne, D. E. et al. Phase transition of computational power in the resource states for one-way quantum computation. New J. Phys. 10, 023010 (2008).

Yoshida, B. Topological color code and symmetry-protected topological phases. Phys. Rev. B 91, 245131 (2015).

Yoshida, B. Gapped boundaries, group cohomology and fault-tolerant logical gates. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1509.03626 (2015).

Cirac, J. I. & Zoller, P. Goals and opportunities in quantum simulation. Nat. Phys. 8, 264–266 (2012).

Georgescu, I. M., Ashhab, S. & Nori, F. Quantum simulation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 153–185 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation grants PHY-1212445, PHY-1314955, PHY-1521016 and PHY-1620651.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplemental Information accompanies the paper on the npj Quantum Information website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Miller, J., Miyake, A. Hierarchy of universal entanglement in 2D measurement-based quantum computation. npj Quantum Inf 2, 16036 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/npjqi.2016.36

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npjqi.2016.36

This article is cited by

-

Finding new multipartite entangled resources for measurement-based quantum computation

Quantum Information Processing (2023)

-

Error-protected qubits in a silicon photonic chip

Nature Physics (2021)

-

Quantum computational universality of hypergraph states with Pauli-X and Z basis measurements

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Resource-efficient verification of quantum computing using Serfling’s bound

npj Quantum Information (2019)