Abstract

Immunisation is a very important aspect of child health. Invasive pneumococcal and influenza diseases have been major vaccine-available communicable diseases. We surveyed demographics and attitudes of parents of primary school students who received pneumococcal conjugate vaccination (PCV) and compared them with those who did not receive pneumococcal vaccination. The survey was carried out in randomly selected primary schools in Hong Kong. Questionnaires were sent to nine primary schools between June and September 2014. Parents of 3,485 children were surveyed, and 3,479 (1,452 PCV immunised, 2,027 un-immunised) valid questionnaires were obtained. Demographic data were generally different between the two groups. PCV-immunised children were more likely to be female (57.0 vs. 52.2%, P=0.005), born in Hong Kong (94.2 vs. 92.3%, P=0.031), have a parent with tertiary education (49.2 vs. 31.8, P<0.0005), from the higher-income group (P=0.005), have suffered upper respiratory infections, pneumonia, otitis media or sinusitis (P=0.019), and have doctor visits in preceding 12 months (P=0.009). They were more likely to have received additional immunisations outside the Hong Kong Childhood Immunization Programme (64.0 vs. 30.6%, P<0.0005) at private practitioner clinics (91.1 vs. 83.5%, P<0.0005). Un-immunised children were more likely to live with senior relatives who had not received PCV. Their parents were less likely to be aware of public education programme on PCV and influenza immunisation, and children were less likely to have received influenza vaccination. The major reasons for PCV immunisations were parent awareness that pneumococcal disease could be severe and vaccines were efficacious in prevention. The major reasons for children not being immunised with PCV were concerns about vaccine side effects, cost, vaccine not efficacious or no recommendation by family doctor or government. In conclusion, PCV unimmunized children were prevalent during the study period. Reportedly, they were generally less likely to have received influenza and other childhood vaccines, and more likely to live with senior relatives who had not received PCV and influenza. These observations provide important demographic data for public health policy in childhood immunisation programme.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Immunisation is a very important aspect of child health. Invasive pneumococcal and influenza diseases have been major communicable diseases for which vaccines are available.1–4 The Hong Kong Childhood Immunization Programme was launched in 2007, and universal pneumococcal conjugate vaccination (PCV )in children was implemented in 2009.5–7 However, certain vaccine-preventable diseases, notably pneumococcal and influenza infections, are still not under control. The influenza and pneumococcal vaccine coverage rates were generally low.8 This study evaluated the knowledge and practices of immunisation associated with these diseases among local parents. With such an understanding, public health effort in education and therapeutics for our patients can be targeted.

Results

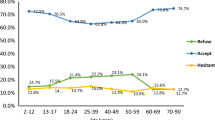

A total of 6,469 questionnaires were sent to nine primary schools between June and September 2014. Parents of 3,485 children were surveyed, and 3,479 (1,452 PCV immunised and 2,027 un-immunised) valid questionnaires were obtained (Table 1). Nine out of 10 parents believed that PCV is important for the health of their children, but only 42% of children had received PCV. Four out of 10 children lived with senior relatives (grandparents), but 7 out of 10 of these senior relatives had not received PCV. Twelve percent of children had a history of chronic conditions including prematurity (5.7%, <37 weeks gestation), asthma (5.4%) and congenital heart disease (0.7%). In terms of demographics and parental attitudes, PCV-immunised children were generally very different from their un-immunised counterparts (Tables 1 and 2). They were more likely to be female (57.0 vs. 52.2% female, P=0.005), born in Hong Kong (94.2 vs. 92.3%, P=0.031), have a parent with tertiary education (49.2 vs. 31.8, P<0.0005), from the higher-income group (HK$60,000+ per month, P=0.005), live in Hong Kong Island or Kowloon peninsula, have suffered from UTI, pneumonia, otitis media or sinusitis (P=0.019) and have doctor visits in the preceding 12 months (P=0.009). They were more likely to have received additional immunisations outside the Hong Kong Childhood Immunization Programme (64.0 vs. 30.6%, P<0.0005) at private practitioner clinics (91.1 vs. 83.5%, P<0.0005). The parents of PCV-immunised children generally believed that PCV, chickenpox, hepatitis A and B virus, rotavirus, influenza, encephalitis and Hemophilus influenzae B immunisation were important for their child. These parents were also more likely to be aware that Streptococcal pneumoniae (SP) infection could be fatal (90.9% vs. 71.5%, P<0.0005), and that it could cause meningitis, pneumonia, otitis media and septicaemia. Un-immunised children were more likely to live with senior relatives who had not received PCV. Their parents were less likely to be aware of public education programme on PCV, as well as influenza immunisation, and less likely to have received influenza vaccination (16.4% vs. 30.8%, P<0.0005). Generally, the majority of informants did not know which PCV their child had received (Table 3). Private practitioners, family doctors and paediatricians were generally important sources of vaccine information. The major reasons for PCV immunisations were parental awareness of the severity of SP disease, PCV being effective in prevention and recommendations by the paediatrician or government. The major reasons for children not being immunised with PCV were concerns about vaccine side effects, cost, vaccine not efficacious and no recommendation by the private practitioner or the government (Table 4).

A binomial logistic regression was performed to ascertain the effects of child’s gender, birth year, Hong Kong born, residing with grandparents, history of respiratory tract-related infections, history of immunisation in Hong Kong, history of influenza immunisation, parents’ highest education, monthly household income, knowledge on the risk of death caused by Pneumococcus, predicted risk of cross-infectivity and knowledge on a local propaganda ‘Left influenza and Right pneumococcus immunization’ on the likelihood that the child has received Pneumococcal vaccine. Child of female gender (odds ratio (OR): 1.22; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.05–1.43; P=0.010), later birth year (OR: 1.42; 95% CI: 1.35–1.49; P<0.0005 for every level increase), with history of influenza immunisation (OR: 2.11; 95% CI: 1.75–2.53; P<0.0005), higher parental education (OR: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.01–1.40; P=0.038 for every level increase), higher monthly household income (OR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.14–1.31; P<0.0005 for every level increase), parents being knowledgeable on the risk of death caused by Pneumococcus (OR: 3.13; 95% CI: 2.50–3.91; P<0.0005) and higher predicted risk of cross-infectivity (OR: 1.29; 95% CI: 1.13–1.46; P<0.0005 for every level increase) were independently associated with increased likelihood of the child being vaccinated with Pneumococcal vaccine.

Discussion

Main findings

This survey reveals many important public health issues for childhood immunisations. A majority of parents are aware that SP and influenza can cause serious disease, but less than half of their children were immunised. Alarmingly, more than half of the children with chronic respiratory disease such as asthma did not receive PCV immunisation. The same phenomenon of low immunisation rates in children with chronic respiratory diseases has been observed by Talbot et al.9 Invasive pneumococcal disease results in higher mortality in children with comorbidity.10 Asthma is a common respiratory disorder among children and is most studied, which is an independent risk factor for invasive and severe pneumococcal disease.11,12 The risk among persons with asthma was at least double compared with that among controls.9

During the winter influenza season, prevention of co-infections with pneumococcal disease continues to be challenging in at-risk population.13–15 In our study, parents reported that the un-immunised children often had senior relatives (usually grandparents) who were also un-immunised. In recent years, the Hong Kong government has advocated and implemented PCV and influenza vaccination in the elderly population. Health education should target both the elderly and the paediatric population to optimise immunisation coverage and to provide more extensive or herd protection to the population at large with these vaccines.2,9

Reportedly, the major reasons for PCV immunisations were that parents were aware that SP disease could be severe and vaccines were efficacious in prevention. The information indicates that public education is important in encouraging or facilitating parents to take up immunisation for their child.3 The major reasons for children who were not immunised with PCV were concerns about vaccine side effects, cost, vaccine not efficacious and no recommendation by the private practitioner, family doctors or government.16 The perceived side effects could be because of publicity of exceedingly rare but exaggerated reports of associated side effects such as Guillain–Barre syndrome, which is not proven to have direct associations with vaccination.17–20

Childhood vaccination in Hong Kong is generally free under a government universal Childhood Immunization Programme.6 Vaccination uptake has generally been excellent for all the conventional vaccines. The low-uptake situation for pneumococcal, influenza or ‘newer’ and more recently introduced vaccines in HK may be primarily because of socioeconomic reasons. General practitioners might not view health promotion programmes as worthwhile, and they are not very familiar with the latest model of health promotion linking to holistic approach of patient care, as reflected in an Australian study.21 A Swiss study has reported general practitioners mentioning low priority of the pneumococcal vaccination in daily practice, as they rarely experienced cases of severe pneumococcal disease in their daily work.22 In Hong Kong, one study has reported that only half of the general practitioner respondents actively recommend pneumococcal vaccination to elderly and only 18.8% would recommend it for middle-aged patients.23 This might explain the low-uptake rate for ‘non-conventional vaccines’. More public awareness and education efforts, together with strong input efforts from healthcare professionals, would be essential to enhance vaccine uptake.6

Strengths and limitations of this study

A strength of this study is the large sample size and standardised questionnaire to ensure uniformity for data. Limitations include the intrinsic problems associated with the use of questionnaire, possible misinterpretation of questions and the relatively low return rate of filled questionnaires. Despite the small number of schools included in this study, detailed demographic data such as household income, guardian’s highest education, past medical and immunisation history allow comprehensive analysis to be performed. There would be clustering of data at the school level, with nine schools involved in the study. The socioeconomic status of the study population as reflected by parental education level and monthly household income (Table 1) is not markedly different from Hong Kong population as a whole.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

The same phenomenon of low immunisation rates in children with chronic respiratory diseases has been observed by Talbot et al.9 Invasive pneumococcal disease results in higher mortality in children with comorbidity.10 Asthma is a common respiratory disorder among children and is most studied, which is an independent risk factor for invasive and severe pneumococcal disease.11,12

Similar to previously reported work, the major reasons for children not being immunised with PCV were concerns about vaccine side effects, cost, vaccine not efficacious and no recommendation by the private practitioner, family doctors or government.16 The perceived side effects could be because of publicity of exceedingly rare but exaggerated reports of associated side effects such as Guillain–Barre syndrome, which is not proven to have direct associations with vaccination.17–20

Implications for future research, policy and practice

PCV-un-immunised children and senior relatives (grandparents) were prevalent during the study period. Public education and facilitation of immunisation of PCV and influenza should target for both at-risk groups of children and the elderly.

Conclusions

PCV-un-immunised children were prevalent during the study period. Parents of PCV-un-immunised children had lower education background and lower income. They were less aware of the potential seriousness of invasive pneumococcal disease. Public education and facilitation of immunisation of PCV and influenza should target for both at-risk groups of children and the elderly.

Materials and methods

This study was a community-based cross-sectional survey in which young children were randomly recruited according to the distribution of their primary schools. Parents of participating subjects were of Chinese ethnicity. After informed consent, questionnaires were sent to children’s families in the schools. The survey was carried out in randomly selected primary schools in Hong Kong. On the basis of the assumption that more than 50% children did not receive influenza vaccination or pneumococcal vaccination, a sample size of 3,000 children from Hong Kong would have a power of 80% at a 95% level of confidence to detect a representable significance. As we conservatively expected a participation rate of 80% among all the subjects, this study aimed to recruit 2,880 primary school children. A complete list of primary schools was obtained from the Education Department of Hong Kong. In participating primary schools, all grades of primary students were targeted for the study. Schools were selected from the three major geographic regions of Hong Kong (Hong Kong Island, Kowloon, New Territories and outlying islands). Sample selection was based on a stratified (by districts) randomised sampling frame. We stratified all schools according to the above three geographic regions. We then selected 10 primary schools randomly from each district. According to data obtained from the Education Department of Hong Kong and our past experience of similar school-based study, each primary school would contribute a minimum of four classes in each grade for the study. Assuming class sizes of 30 and a parental co-operation rate of 80%, approximately 2,880 students would be recruited. This sampling method would ensure that our sample can truly be representative of the young children in Hong Kong.

A standard questionnaire in Chinese was used to screen for the medical history of pulmonary diseases. We added items to assess also the participation of the Childhood Immunization Programme. Consent was first obtained from headmasters or principals of all primary schools. Parents in these consented schools were then given standard written questionnaires to be completed at home and collected within 1 week of distribution. The questionnaire was modified from a previously used version, which gathered demographic data, medical history of upper respiratory diseases, awareness vaccine-preventable diseases, severity of certain vulnerable diseases and acceptance of vaccination.

Data entry and statistical analyses

The research assistant conducting the questionnaire survey entered all the data into a database, and an independent research staff validated the accuracy of the entered data. Data were categorised and analysed using SPSS (Statistical package for the social sciences for Windows). Chi-square test was used to compare the prevalence rates between different schools. Logistic regression with adjustment for covariates was used to estimate the possible associations between self-reported influenza and pneumococcal diseases with SPSS v.18 (IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA). P values (two-tailed) less than 0.05 were considered significant. Approval for the clinical research ethics was obtained from The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong—New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee. Parents or legal guardians of the children signed consent before they joined this study.

References

WHO Publication. Pneumococcal vaccines WHO position paper - 2012 - recommendations. Vaccine 30, 4717–4718 (2012).

Robinson, K. A. et al. Epidemiology of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections in the United States, 1995-1998: Opportunities for prevention in the conjugate vaccine era. JAMA 285, 1729–1735 (2001).

Pilishvili T. et al. Risk factors for invasive pneumococcal disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccine use. Pediatrics 2010; 126, e9–e17.

Moore, M. R. et al. Effect of use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children on invasive pneumococcal disease in children and adults in the USA: analysis of multisite, population-based surveillance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 15, 301–309 (2015).

Hon, K. L. et al. Cardiopulmonary morbidity of streptococcal infections in a PICU. Clin. Respir. J. 10, 45–52 (2014).

Tam W. W. et al. Parental attitudes and factors associated with varicella vaccination in preschool and schoolchildren in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015; 94, e1519.

Hon, K. L. et al. Childhood pneumococcal diseases and serotypes: can vaccines protect? Indian J. Pediatr. 77, 1387–1391 (2010).

Yang, T. U., Song, J. Y., Noh, J. Y., Cheong, H. J. & Kim, W. J. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccine coverage rates among patients admitted to a teaching hospital in South Korea. Infect. Chemother. 47, 41–48 (2015).

Talbot, T. R. et al. Asthma as a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 2082–2090 (2005).

Yildirim, I., Shea, K. M., Little, B. A., Silverio, A. L. & Pelton, S. I. Vaccination, underlying comorbidities, and risk of invasive pneumococcal disease. Pediatrics 135, 495–503 (2015).

Juhn, Y. J. et al. Increased risk of serious pneumococcal disease in patients with asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 122, 719–723 (2008).

Hsu, K. K., Shea, K. M., Stevenson, A. E. & Pelton, S. I. Underlying conditions in children with invasive pneumococcal disease in the conjugate vaccine era. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 30, 251–253 (2011).

Tromp, K. M., Campbell, M. W. & Vazquez, A. Recent developments and future directions of Pneumococcal vaccine recommendations. Clin. Ther. 15, 10 (2015).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among children aged 6-18 years with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 62, 521–524 (2013).

Nuorti, J. P. & Whitney, C. G. Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children - use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine - recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm. Rep. 59, 1–18 (2010).

Yousef, E. & Mannan, S. Systemic reaction to pneumococcal vaccine: how common in pediatrics? Allergy Asthma Proc. 29, 397–399 (2008).

Baxter, R. et al. Lack of association of Guillain-Barre syndrome with vaccinations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 57, 197–204 (2013).

Vellozzi, C., Iqbal, S. & Broder, K. Guillain-Barre syndrome, influenza, and influenza vaccination: the epidemiologic evidence. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, 1149–1155 (2014).

Vellozzi, C., Iqbal, S., Stewart, B., Tokars, J. & DeStefano, F. Cumulative risk of Guillain-Barre syndrome among vaccinated and unvaccinated populations during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Am. J. Public Health 104, 696–701 (2014).

Verity, C. et al. Pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza vaccination, preceding infections and clinical findings in UK children with Guillain-Barre syndrome. Arch. Dis. Child. 99, 532–538 (2014).

Achhra, A. Health promotion in Australian general practice: a gap in GP training. Aust. Fam. Physician 38, 605–608 (2009).

Badertscher, N., Morell, S., Rosemann, T. & Tandjung, R. General practitioners' experiences, attitudes, and opinions regarding the pneumococcal vaccination for adults: a qualitative study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 5, 967–974 (2012).

Mui, L. W., Chan, A. Y., Lee, A. & Lee, J. Cross-sectional study on attitudes among general practitioners towards pneumococcal vaccination for middle-aged and elderly population in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE 8, e78210 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank the parents and the schools for helping with this survey.

Funding

K-LEH was commissioned by the Hong Kong Society of Paediatric Respirology and Allergy, and received a small commission of approximately US$2,000 for his department.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

K-LEH is the principal author. YCKT performed the statistical analyses. LCNC, DKKN, TYM, JYC and AL helped in drafting of the manuscript. TFL is an allergist/infectious disease professor who helped in drafting of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The principal author K-LEH was commissioned by the Hong Kong Society of Paediatric Respirology and Allergy to perform this survey. K-LEH has previously received travel and conference sponsorships from WyethNutrition, Pfizer and GSK. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hon, K., Tsang, Y., Chan, L. et al. A community-based cross-sectional immunisation survey in parents of primary school students. npj Prim Care Resp Med 26, 16011 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2016.11

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2016.11