Abstract

A Weyl semimetal is a novel topological phase of matter1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16, in which Weyl fermions arise as pseudo-magnetic monopoles in its momentum space. The chirality of the Weyl fermions, given by the sign of the monopole charge, is central to the Weyl physics, since it directly serves as the sign of the topological number5,15 and gives rise to exotic properties such as Fermi arcs5,9,12 and the chiral anomaly15,16,17,18,19. Here, we directly detect the chirality of the Weyl fermions by measuring the photocurrent in response to circularly polarized mid-infrared light. The resulting photocurrent is determined by both the chirality of Weyl fermions and that of the photons. Our results pave the way for realizing a wide range of theoretical proposals15,16,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 for studying and controlling the Weyl fermions and their associated quantum anomalies by optical and electrical means. More broadly, the two chiralities, analogous to the two valleys in two-dimensional materials31,32, lead to a new degree of freedom in a three-dimensional crystal with potential novel pathways to store and carry information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In 1929, H. Weyl discovered that all elementary fermions that have zero mass must attain a definitive chirality determined by whether the directions of spin and motion are parallel or anti-parallel1. Such a chiral massless fermion is called the Weyl fermion (WF). Although none of the fundamental particles in high-energy physics was identified as WFs, condensed matter researchers have found an analogue of this elusive particle in a new class of topological materials, the Weyl semimetal (WSM)2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Similar to the case in high-energy physics, the WFs in a WSM also have a definitive chirality. A right-handed Weyl node (χ = +1) is a monopole (a source) of Berry curvature whereas a left-handed Weyl node (χ = −1) is an anti-monopole (a drain) of Berry curvature. Any Fermi surface enclosing a right(left)-handed Weyl node (χ = ±1) has a unit Berry flux coming out (in) and hence carries a Chern number C = ±1 (Fig. 1a). As a result, the chirality of the WF serves as its topological number.

a, The blue and green arrows depict the Berry curvatures in momentum space. The grey spheres represent the Fermi surfaces that enclose the Weyl nodes. b, Surface band structures along the closed k loops in the surface Brillouin zone (BZ) defined by the dashed circles in a. c, Chirality selection rule: Right-handed circularly polarized (RCP) light along  excites the +kz side of the χ = +1 Weyl node but the −kz side of the χ = −1 Weyl node. Chirality selection rule is independent of the tilt of the WFs. d, In the presence of a finite tilt and a finite chemical potential away from the Weyl node, the Pauli blockade becomes asymmetric about the nodal point. e,f, Optical excitation scheme for a pair of untilted or tilted Weyl cones, respectively. The colour map on the sphere schematically shows the magnitude of the matrix element (that is, the transition probability considering both the chirality selection rule and the Paul blockade) at different solid angles. The currents from a pair of untilted WFs of opposite chirality cancel whereas those from a pair of tilted WFs do not necessarily cancel. g–i, Crystal structure of TaAs shown from different perspectives. j, Distribution of the 24 Weyl nodes in the BZ of TaAs. We denote the 8 Weyl nodes in the kz = 0 plane (grey) as W1 and the 16 Weyl nodes in the upper and lower kz planes (pink) as W2. The green and blue colours denote positive and negative chiralities, respectively.

excites the +kz side of the χ = +1 Weyl node but the −kz side of the χ = −1 Weyl node. Chirality selection rule is independent of the tilt of the WFs. d, In the presence of a finite tilt and a finite chemical potential away from the Weyl node, the Pauli blockade becomes asymmetric about the nodal point. e,f, Optical excitation scheme for a pair of untilted or tilted Weyl cones, respectively. The colour map on the sphere schematically shows the magnitude of the matrix element (that is, the transition probability considering both the chirality selection rule and the Paul blockade) at different solid angles. The currents from a pair of untilted WFs of opposite chirality cancel whereas those from a pair of tilted WFs do not necessarily cancel. g–i, Crystal structure of TaAs shown from different perspectives. j, Distribution of the 24 Weyl nodes in the BZ of TaAs. We denote the 8 Weyl nodes in the kz = 0 plane (grey) as W1 and the 16 Weyl nodes in the upper and lower kz planes (pink) as W2. The green and blue colours denote positive and negative chiralities, respectively.

The distinct chirality directly leads to exotic, topologically protected phenomena in a WSM. First, the separation between WFs of opposite chirality in k space protects them from being gapped out5. Second, the opposite Chern numbers of the bulk Fermi surfaces guarantee the existence of topological Fermi arc surface states5 that connect between Weyl nodes of opposite chirality (Fig. 1a, b). Third, applying parallel electric and magnetic fields can break the apparent conservation of chirality, making a Weyl metal, unlike ordinary non-magnetic metals, more conductive with an increasing magnetic field17,18,19. Besides its fundamental importance in the topological physics of WSM, the chirality also gives rise to a new degree of freedom in three-dimensional (3D) materials, analogous to the valley degree of freedom in the two-dimensional (2D) transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) that have gathered great attention recently31,32. The potential to control the chirality15,16,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29, combined with the high electron mobility found in the WSMs18, may offer new schemes to encode and process information.

Therefore, it is of crucial importance to detect the chirality of the WFs. This requires identifying physical observables that are sensitive to the WF chirality. The band structures, quasi-particle interferences, magneto-resistances measured by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES)9,11,12,13,14, scanning tunnelling microscope33,34,35, and transport experiments17,18,19, respectively, are not sensitive to the chirality of WFs (see also Supplementary Information VII). One proposal to detect the chirality is to use pump–probe ARPES to measure the transient spectral weight upon shining circularly polarized pump light36. However, this requires an ARPES with a mid-infrared pump and a soft X-ray probe, which is technically very challenging. On the other hand, optical experiments on WSMs have remained very limited37,38, although they are promising approaches to achieve these goals15. In this paper, we detect the chirality of the WFs in the WSM TaAs by measuring its mid-infrared photocurrent response. Photocurrents induced by circularly polarized light, also called the circular photogalvanic effect (CPGE), have been previously measured in other systems39,40,41,42,43, but have not been experimentally studied in WSMs.

We first discuss the theoretical picture of the CPGE for optical transitions from the lower part of the Weyl cone to the upper part20. There are two independent factors important for the CPGE here. The first is the chirality selection rule (Fig. 1c, e). For a right circularly polarized (RCP) light propagating along  and a χ = +1 WF, the optical transition is allowed on the +kz side but forbidden on the −kz side due to the conservation of angular momentum20,24,36. The second is the Pauli blockade, which is present only when the chemical potential is away from the Weyl node. In the presence of a finite tilt (Fig. 1d), the Pauli blockade becomes asymmetric about the nodal point. If we consider only a single Weyl cone, in general we expect a nonzero current (Fig. 1c, d). However, having a nonzero total photocurrent depends on whether contributions from different WFs cancel each other. In an inversion-breaking WSM with mirror symmetries, ref. 20 shows that the total photocurrent becomes nonvanishing when both factors are present (Supplementary Information IV.1).

and a χ = +1 WF, the optical transition is allowed on the +kz side but forbidden on the −kz side due to the conservation of angular momentum20,24,36. The second is the Pauli blockade, which is present only when the chemical potential is away from the Weyl node. In the presence of a finite tilt (Fig. 1d), the Pauli blockade becomes asymmetric about the nodal point. If we consider only a single Weyl cone, in general we expect a nonzero current (Fig. 1c, d). However, having a nonzero total photocurrent depends on whether contributions from different WFs cancel each other. In an inversion-breaking WSM with mirror symmetries, ref. 20 shows that the total photocurrent becomes nonvanishing when both factors are present (Supplementary Information IV.1).

TaAs has been experimentally established as an inversion-breaking WSM with mirror symmetries7,8,9,12. The tilt of the WFs is significant (for example, |v+/v−| ≥ 2, see Fig. 1d and Supplementary Information III.3) and the chemical potential is ∼18 meV away from the W1 Weyl nodes (Supplementary Information III.2). These factors make TaAs a promising system in which to observe the WF-induced CPGE as discussed above. We describe the following properties of TaAs relevant for our study. Although TaAs has twenty-four WFs, only two are independent, which are highlighted in Fig. 1j and named W1 and W2. The other twenty-two Weyl nodes can be related by the system’s symmetries (see Supplementary Information I), including time reversal ( ), four-fold rotation around

), four-fold rotation around  (C4c) and two mirror reflections about the (b, c) and (a, c) planes (

(C4c) and two mirror reflections about the (b, c) and (a, c) planes ( and

and  ). Moreover, since the crystal lacks mirror symmetry

). Moreover, since the crystal lacks mirror symmetry  ,

,  can be unambiguously defined as the direction going from the Ta atom to the As atom across the dotted line in Fig. 1h. With this well-defined lattice (Fig. 1g–i) as an input, first-principles calculations have predicted the energy dispersion and the chirality of each WF (Fig. 1j). Although the energy dispersion has been observed by ARPES9,11,12,13,14, the chirality configuration (Fig. 1j) has not been measured.

can be unambiguously defined as the direction going from the Ta atom to the As atom across the dotted line in Fig. 1h. With this well-defined lattice (Fig. 1g–i) as an input, first-principles calculations have predicted the energy dispersion and the chirality of each WF (Fig. 1j). Although the energy dispersion has been observed by ARPES9,11,12,13,14, the chirality configuration (Fig. 1j) has not been measured.

To detect the CPGE, we utilize a mid-infrared scanning photocurrent microscope (Fig. 2a) equipped with a CO2 laser source (wavelength λCO2 = 10.6 μm and energy ℏω ≃ 120 meV). We note that this photon energy fits our purpose because we specifically want to excite electrons from the lower part of Weyl cone to the upper part. A much lower photon energy (in the terahertz range) will probably fall into the intra-band regime unless the chemical potential is tuned very close to the Weyl nodes, whereas a much higher photon energy would excite electrons to bands at much higher energy, making the process of marginal relevance to the Weyl physics. Throughout the paper, we assign the direction of propagation of the light as  . Our TaAs sample (Fig. 2b) is purposely filed down so that the out-of-plane direction is

. Our TaAs sample (Fig. 2b) is purposely filed down so that the out-of-plane direction is  . We have performed single-crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD, see SI.III.5), which allows us to determine the

. We have performed single-crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD, see SI.III.5), which allows us to determine the  direction (Fig. 2b). Throughout Fig. 2, the lab and sample coordinates are identical (for example,

direction (Fig. 2b). Throughout Fig. 2, the lab and sample coordinates are identical (for example,  ). The black data points in Fig. 2c show the current along

). The black data points in Fig. 2c show the current along  , when the laser spot is near the sample’s centre (the black dot in Fig. 2b). We observe that the current reaches maximum value for RCP light, minimum for LCP light, and zero for linearly polarized light. The whole data curve fits nicely to a cosine function. In sharp contrast, we see no observable current along the

, when the laser spot is near the sample’s centre (the black dot in Fig. 2b). We observe that the current reaches maximum value for RCP light, minimum for LCP light, and zero for linearly polarized light. The whole data curve fits nicely to a cosine function. In sharp contrast, we see no observable current along the  direction (the black data points in Fig. 2d).

direction (the black data points in Fig. 2d).

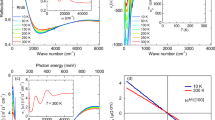

a, Schematic illustration of the mid-IR photocurrent microscope setup. We used a laser power about 10 mW throughout the main text. b, A photograph of the measured TaAs sample. The crystal axes a, b, c are denoted. Scale bar: 300 μm. c,d, Polarization-dependent photocurrents at T = 10 K measured along the  (c) or

(c) or  (d) direction with the laser applied at the horizontally (c) or vertically (d) aligned pink, black and blue dots in b. LCP, left-handed circularly polarized. e, Colour map showing the photocurrent measured along b with a fixed polarization (RCP) while the laser spot is varied in (b, c) space. Contacts and sample edges are traced by black solid and green dashed lines, respectively. f, Photocurrent as a function of polarization and the c position of the laser spot. The b position of the laser spot is fixed at the dashed line in e. g, Fourier transform of e from polarization angle (θ) space to frequency (f) space. h–j, Frequency-filtered photocurrents only at the frequency of 1/π.

(d) direction with the laser applied at the horizontally (c) or vertically (d) aligned pink, black and blue dots in b. LCP, left-handed circularly polarized. e, Colour map showing the photocurrent measured along b with a fixed polarization (RCP) while the laser spot is varied in (b, c) space. Contacts and sample edges are traced by black solid and green dashed lines, respectively. f, Photocurrent as a function of polarization and the c position of the laser spot. The b position of the laser spot is fixed at the dashed line in e. g, Fourier transform of e from polarization angle (θ) space to frequency (f) space. h–j, Frequency-filtered photocurrents only at the frequency of 1/π.

We move the light spot horizontally to the blue and pink dots in Fig. 2b. The corresponding photocurrents (the blue and pink data points in Fig. 2c) show the same polarization dependence but with an additional, polarization-independent shift. We also see the same polarization-independent shift for the currents along  (Fig. 2d). These data reveal two distinct mechanisms for photocurrent generation. To understand the polarization-independent component, in Fig. 2e, we show the photocurrent along

(Fig. 2d). These data reveal two distinct mechanisms for photocurrent generation. To understand the polarization-independent component, in Fig. 2e, we show the photocurrent along  with a fixed polarization (RCP), while the laser spot is varied in (y, z) space. We see the current flowing to the opposite directions depending on whether the light spot is closer to the left or right contact. This spatial dependence shows that the polarization-independent component arises from the photo-thermal effect39,40,44. Essentially, because the sample and contact have different thermopower, a current is generated by the laser-induced temperature gradient. Figure 2f shows the photocurrent as a function of polarization and the z position of the laser spot, where both the polarization-dependent and polarization-independent components can be seen. In order to separate these two components, we Fourier transform from the polarization angle space to the frequency space. As shown in Fig. 2g, aside from the low-frequency intensities that correspond to the polarization-independent photo-thermal current, we observe a sharp peak exclusively at a frequency of 1/π. This peak disappears at the z values outside the sample, confirming that the observed current is the sample’s intrinsic property. We show the frequency-filtered photocurrent only at a frequency of 1/π. The RCP (Fig. 2h) light induced photocurrent is along the

with a fixed polarization (RCP), while the laser spot is varied in (y, z) space. We see the current flowing to the opposite directions depending on whether the light spot is closer to the left or right contact. This spatial dependence shows that the polarization-independent component arises from the photo-thermal effect39,40,44. Essentially, because the sample and contact have different thermopower, a current is generated by the laser-induced temperature gradient. Figure 2f shows the photocurrent as a function of polarization and the z position of the laser spot, where both the polarization-dependent and polarization-independent components can be seen. In order to separate these two components, we Fourier transform from the polarization angle space to the frequency space. As shown in Fig. 2g, aside from the low-frequency intensities that correspond to the polarization-independent photo-thermal current, we observe a sharp peak exclusively at a frequency of 1/π. This peak disappears at the z values outside the sample, confirming that the observed current is the sample’s intrinsic property. We show the frequency-filtered photocurrent only at a frequency of 1/π. The RCP (Fig. 2h) light induced photocurrent is along the  direction irrespective of the location of the laser. This spatial configuration is different from that of the photo-thermal effect (Fig. 2e). In Supplementary Fig. 4, we further show the temperature and laser power dependences of the photocurrent. In particular, we found that the photo-thermal effect and the CPGE have opposite temperature trends. These systematic polarization-, position-, temperature- and power-dependent measurements further confirm the CPGE and isolate it from the photo-thermal effect.

direction irrespective of the location of the laser. This spatial configuration is different from that of the photo-thermal effect (Fig. 2e). In Supplementary Fig. 4, we further show the temperature and laser power dependences of the photocurrent. In particular, we found that the photo-thermal effect and the CPGE have opposite temperature trends. These systematic polarization-, position-, temperature- and power-dependent measurements further confirm the CPGE and isolate it from the photo-thermal effect.

We now present two important characteristics of the observed photocurrent. The first is the cancellation of photocurrent along certain directions. For RCP light along  (Fig. 2), we observe zero current along

(Fig. 2), we observe zero current along  . On another TaAs sample (Supplementary Fig. 24), we shine light along

. On another TaAs sample (Supplementary Fig. 24), we shine light along  . We observe zero current along both the

. We observe zero current along both the  and

and  directions. The second is the sign reversal of the photocurrent upon rotating the sample by 180° while fixing the properties of the light (Fig. 3). The lab coordinate remains constant while the sample coordinate changes upon rotations. The measured photocurrent I > 0 is consistently defined as

directions. The second is the sign reversal of the photocurrent upon rotating the sample by 180° while fixing the properties of the light (Fig. 3). The lab coordinate remains constant while the sample coordinate changes upon rotations. The measured photocurrent I > 0 is consistently defined as  in the lab coordinate. For a given polarization, the direction of the photocurrent reverses if one rotates the sample by 180° around

in the lab coordinate. For a given polarization, the direction of the photocurrent reverses if one rotates the sample by 180° around  or

or  (Fig. 3b, c), while it remains the same upon a rotation around

(Fig. 3b, c), while it remains the same upon a rotation around  (Fig. 3d). To explain these observations, we consider the second-order photocurrent response tensor ηαβγ (the tensor indices span the sample coordinate components {a, b, c}) since our CPGE shows a linear dependence on the laser power (Supplementary Fig. 4c). ηαβγ is defined through:

(Fig. 3d). To explain these observations, we consider the second-order photocurrent response tensor ηαβγ (the tensor indices span the sample coordinate components {a, b, c}) since our CPGE shows a linear dependence on the laser power (Supplementary Fig. 4c). ηαβγ is defined through:

where J is the total photocurrent and E is the electric field. The CPGE corresponds to the imaginary part of ηαβγ (refs 38,41,42,43). Because the ηαβγ tensor is an intrinsic property, it has to obey the symmetries of the system. Therefore, symmetry dictates many important properties of the CPGE, independent of the details of the band structure, the wavelength of the light, or the underlying microscopic mechanism for the optical transition. In TaAs, the presence of  and

and  forces ηαβγ to vanish when it contains an odd number of momentum index a or b. In Supplementary Information IV.2, we show that both observations can be explained by symmetry analysis of the tensor ηαβγ, which further confirms the intrinsic nature of the observed CPGE.

forces ηαβγ to vanish when it contains an odd number of momentum index a or b. In Supplementary Information IV.2, we show that both observations can be explained by symmetry analysis of the tensor ηαβγ, which further confirms the intrinsic nature of the observed CPGE.

a, Repetition of Fig. 2c. Both the laboratory coordinate ( ) and the sample coordinate (

) and the sample coordinate ( ) are noted. I > 0 is defined as along the

) are noted. I > 0 is defined as along the  direction in the laboratory framework. b–d, Photocurrent measurements after a 180° rotation of the sample around

direction in the laboratory framework. b–d, Photocurrent measurements after a 180° rotation of the sample around  ,

,  or

or  (C2a, C2b, or C2c), respectively.

(C2a, C2b, or C2c), respectively.

Whereas the cancellation and sign reversal are dictated solely by symmetry, the absolute direction of the current—that is, the sign of ηbbc and ηbcb—depends on the microscopic mechanism. Specifically, when we shine light along  , symmetry tells us the current will be nonzero along

, symmetry tells us the current will be nonzero along  but it cannot decide whether the current flows to

but it cannot decide whether the current flows to  or

or  (Fig. 2). Unlike a high photon energy, which would probably involve many bands irrelevant to the WFs, the photon energy of 120 meV creates excitations from the lower part of the Weyl cone to the upper part, which directly relies on the chirality of the WFs (Fig. 1). Moreover, the microscopic theory describing this optical transition is available20, which allows us to theoretically calculate the photocurrent (in Supplementary Information V, we further exclude other mechanisms). Specifically, the photocurrent from a single WF is given by

(Fig. 2). Unlike a high photon energy, which would probably involve many bands irrelevant to the WFs, the photon energy of 120 meV creates excitations from the lower part of the Weyl cone to the upper part, which directly relies on the chirality of the WFs (Fig. 1). Moreover, the microscopic theory describing this optical transition is available20, which allows us to theoretically calculate the photocurrent (in Supplementary Information V, we further exclude other mechanisms). Specifically, the photocurrent from a single WF is given by

where C is a constant determining the magnitude of the current that is the same for all 24 WFs,  is a dimensionless vector that gives the direction of the current, q is the momentum vector from the Weyl node, E±, v±, and n±0(μ, q) are the energies, group velocities, and equilibrium distribution functions for the upper (+) and lower (−) parts of the Weyl cone (the Pauli blockade sets in through the chemical potential μ in n±0), ω and A are the frequency and vector potential of the light, and V+− is the optical transition matrix element, which depends on the chirality selection rule through χ and A. Interestingly, the chemical potential of TaAs is known from previous transport experiments18,19 to be very close to the W2 Weyl node. Our quantum oscillation measurements (Supplementary Information III.2) confirmed this case (μ is 17.8 meV above W1 and 4.8 meV above W2). Since the Pauli blockade vanishes for chemical potential at the Weyl node, the photocurrent contribution from W2 WFs is negligibly small. Therefore, our photocurrent solely probes the chirality of a single W1 WF (the other seven W1 WFs are automatically related by symmetries). Assuming RCP light propagating along

is a dimensionless vector that gives the direction of the current, q is the momentum vector from the Weyl node, E±, v±, and n±0(μ, q) are the energies, group velocities, and equilibrium distribution functions for the upper (+) and lower (−) parts of the Weyl cone (the Pauli blockade sets in through the chemical potential μ in n±0), ω and A are the frequency and vector potential of the light, and V+− is the optical transition matrix element, which depends on the chirality selection rule through χ and A. Interestingly, the chemical potential of TaAs is known from previous transport experiments18,19 to be very close to the W2 Weyl node. Our quantum oscillation measurements (Supplementary Information III.2) confirmed this case (μ is 17.8 meV above W1 and 4.8 meV above W2). Since the Pauli blockade vanishes for chemical potential at the Weyl node, the photocurrent contribution from W2 WFs is negligibly small. Therefore, our photocurrent solely probes the chirality of a single W1 WF (the other seven W1 WFs are automatically related by symmetries). Assuming RCP light propagating along  , this theory predicts a photocurrent (

, this theory predicts a photocurrent ( ) along

) along  given by (Supplementary Information III.4 and Supplementary Information IV.3)

given by (Supplementary Information III.4 and Supplementary Information IV.3)

where χW1 is the chirality of the W1 WF highlighted in Fig. 4a. In other words, theory predicts that, if χW1 = +1, then  is along

is along  and that if χW1 = −1, then

and that if χW1 = −1, then  is along

is along  . In our data (Fig. 4b), because we shine RCP light along

. In our data (Fig. 4b), because we shine RCP light along  and measure a current flowing to

and measure a current flowing to  and because we have measured

and because we have measured  from single-crystal XRD, we observe the following relation from our data:

from single-crystal XRD, we observe the following relation from our data:

a, Our calculations (see Supplementary Information III.4) show  . b, By measuring the direction of the current

. b, By measuring the direction of the current  and knowing the polarization and propagation direction of the light, we obtain

and knowing the polarization and propagation direction of the light, we obtain  from data. By comparing theory and data, we obtain χW1 = +1. The χW1 = +1 determined by the photocurrent agrees with that predicted by first principles (Fig. 1j), further confirming our experimental detection of WF chirality. c–e, Comparison between the chirality degree of freedom of the WFs and valley degree of freedom in gapped Dirac system. c, In a gapped Dirac system, an optical excitation with a particular handedness can only populate one valley. d, In the Weyl system, an optical excitation with a particular handedness populates only one side of a single Weyl node. e, By applying parallel electric and magnetic fields, electrons can be pumped from one Weyl cone to the other of opposite chirality due to the chiral anomaly.

from data. By comparing theory and data, we obtain χW1 = +1. The χW1 = +1 determined by the photocurrent agrees with that predicted by first principles (Fig. 1j), further confirming our experimental detection of WF chirality. c–e, Comparison between the chirality degree of freedom of the WFs and valley degree of freedom in gapped Dirac system. c, In a gapped Dirac system, an optical excitation with a particular handedness can only populate one valley. d, In the Weyl system, an optical excitation with a particular handedness populates only one side of a single Weyl node. e, By applying parallel electric and magnetic fields, electrons can be pumped from one Weyl cone to the other of opposite chirality due to the chiral anomaly.

By comparing equation (3) with equation (4), we determine χW1 = +1. We find that the chirality of the W1 WF determined by the photocurrent agrees with that predicted by first principles (Fig. 1j). The agreement further confirms our detection of the WF chirality in TaAs.

Looking forward, it would be valuable to test the observed CPGE effect in hole-doped samples, where the contribution from the W2 Weyl nodes may dominate. Since, at present, all as-grown TaAs samples haven been found to be electron-doped with a chemical potential similar to ours18,19, the hole-doped TaAs may be achieved by chemical doping (for example, Ti, Zr, Si, or Ge) or by electrical gating in thin-film samples. It would also be interesting to investigate the dependence on the photon energy, especially in the terahertz range (for example, ℏω ≤ 10 meV). Finally, it is helpful to study the relaxation time τ via optical pump–probe experiments in the mid-infrared regime.

Finally, we discuss how our results can open up new experimental possibilities for studying and controlling the WFs and their associated quantum anomalies. Analogous to two valleys in two dimensions (Fig. 4c), the key is to identify ways to interact with the two chiralities in a WSM distinctly. In the present study, this is achieved because the circularly polarized light excites opposite sides of the WFs of opposite chirality (Fig. 4d). Another approach to differentiate the two chiralities is to create a population imbalance (Fig. 4e). Interestingly, doing so in a WSM fundamentally requires breaking the apparent conservation of chirality (the chiral anomaly). This can be achieved electrically by applying parallel electric and magnetic fields (Fig. 4e)16,17,18,19, or optically through the chiral magnetic effect by shining a light on a special kind of WSM, where Weyl nodes of opposite chirality have different energies21,27,28,29,30. Apart from the present study and the proposed anomaly-related physics16,21,27,28,29,30, the nontrivial Berry curvatures in WSMs can also lead to various novel optical phenomena such as photocurrents22,23,24,25, Hall voltages26, Kerr rotations23, and second-harmonic generations23,25. Although these novel phenomena16,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 may arise from different aspects of Weyl physics, they are ultimately rooted in the existence of two distinct chiralities (χ = ±1) of WFs, as demonstrated here.

Methods

Mid-infrared photocurrent microscopy setup.

In our experiment, the sample is contacted with metal wires and placed in an optical scanning microscope setup that combines electronic transport measurements with light illumination44,45. The laser source is a temperature-stabilized CO2 laser with a wavelength λ = 10.6 μm (energy ℏω ≃ 120 meV). A focused beam spot (diameter d ≈ 50 μm) is scanned (using a two-axis piezo-controlled scanning mirror) over the entire sample and the current is recorded at the same time to form a colour map of photocurrent as a function of spatial positions. Reflected light from the sample is collected to form a simultaneous reflection image of the sample. The absolute location of the photo-induced signal is therefore found by comparing the photocurrent map to the reflection image. The light is first polarized by a polarizer and the chirality of light is further modulated by a rotatable quarter-wave plate characterized by an angle θ (Fig. 2a).

Single-crystal growth.

Single crystals of TaAs were prepared by the standard chemical vapour transfer (CVT) method46. The polycrystalline samples were prepared by heating up stoichiometric mixtures of high-quality Ta (99.98%) and As (99.999%) powders in an evacuated quartz ampoule. Then the powder of TaAs (300 mg) and the transport agent were sealed in a long evacuated quartz ampoule (30 cm). The end of the sealed ampoule was placed horizontally at the centre of a single-zone furnace. The central zone of the furnace was slowly heated up to 1,273 K and kept at the temperature for five days, while the cold end was less than 973 K. Magneto-transport measurements were performed using a Quantum Design Physical Property Measurement System.

First-principles calculations.

First-principles calculations were performed by the OPENMX code within the framework of the generalized gradient approximation of density functional theory47. Experimental lattice parameters were used46. A real-space tight-binding Hamiltonian was obtained by constructing symmetry-respecting Wannier functions for the As p and Ta d orbitals without performing the procedure for maximizing localization.

Photocurrent calculations.

We elaborate on the methods of photocurrent calculation. For a single Weyl node, the photocurrent density due to a deviation of the electronic distribution δnl(q) = nl(q) − nl0(q) is:

where l = +, − represents the upper part (+) and lower part (−) of the Weyl cone, Δv(q) = v+(q) − v−(q) is the velocity of each particle–hole pair. Then, based on the relaxation time approximation and Fermi’s golden rule, we have:

where V is the electron–light coupling responsible for photoexcitations from |q−〉 to |q+〉 and ΔE(q) = E+(q) − E−(q). We first numerically extract an effective k ⋅ p Weyl Hamiltonian H(k) from ab initio band structure calculation. Then, by the Peierls substitution, the coupling Hamiltonian is calculated as V = H(k + A(t)) − H(A), where A is the vector potential. Rewriting the integrand in dimensionless quantities,

C determines the order of magnitude of the current. The dimensionless vector  , which is of order one, determines the direction of the current. We note that the terms in

, which is of order one, determines the direction of the current. We note that the terms in  depend on system details. For example, δ((ΔE(q)/ℏω) − 1) and n−0(q) − n+0(q) depend on the band structure of the sample; 〈q+ |(V/(ℏvFA/2))| q−〉 depends on both the wavefunctions of the WFs in the sample and the properties of the light.

depend on system details. For example, δ((ΔE(q)/ℏω) − 1) and n−0(q) − n+0(q) depend on the band structure of the sample; 〈q+ |(V/(ℏvFA/2))| q−〉 depends on both the wavefunctions of the WFs in the sample and the properties of the light.

In the following, we show calculation results of  in TaAs under different conditions measured in experiments.

in TaAs under different conditions measured in experiments.

For RCP along  ,

,  and

and  .

.

For RCP along  ,

,  and

and  .

.

Indeed, we see that the current along  is finite for a RCP along

is finite for a RCP along  . In the other three cases, the current is zero due to cancellation.

. In the other three cases, the current is zero due to cancellation.

Data availability.

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Weyl, H. Elektron und gravitation. Z. Phys. 56, 330–352 (1929).

Volovik, G. E. The Universe in a Helium Droplet (Oxford Univ. Press, 2003).

McEuen, P. L. et al. Disorder, pseudospins, and backscattering in carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 5098–5101 (1999).

Murakami, S. Phase transition between the quantum spin Hall and insulator phases in 3D: emergence of a topological gapless phase. New J. Phys. 9, 356 (2007).

Wan, X., Turner, A. M., Vishwanath, A. & Savrasov, S. Y. Topological semimetal and Fermi-arc surface states in the electronic structure of pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 83, 205101 (2011).

Burkov, A. A. & Balents, L. Weyl semimetal in a topological insulator multilayer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 127205 (2011).

Huang, S. M. et al. A Weyl fermion semimetal with surface Fermi arcs in the transition metal monopnictide TaAs class. Nat. Commun. 6, 7373 (2015).

Weng, H. et al. Weyl semimetal phase in non-centrosymmetric transition metal monophosphides. Phys. Rev. X 5, 011029 (2015).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Discovery of a Weyl fermion semimetal and topological Fermi arcs. Science 349, 613–617 (2015).

Lu, L. et al. Observation of Weyl points in a photonic crystal. Science 349, 622–624 (2015).

Lv, B. Q. et al. Experimental discovery of Weyl semimetal TaAs. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031013 (2015).

Lv, B. Q. et al. Observation of Weyl nodes in TaAs. Nat. Phys. 11, 724–727 (2015).

Yang, L. X. et al. Weyl semimetal phase in the non-centrosymmetric compount TaAs. Nat. Phys. 11, 728–733 (2015).

Belopolski, I. et al. Criteria for directly detecting topological Fermi arcs in Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 066802 (2016).

Jia, S., Xu, S.-Y. & Hasan, M. Z. Weyl semimetals, Fermi arcs and chiral anomalies. Nat. Mater. 15, 1140–1144 (2016).

Parameswaran, S. A. et al. A. Probing the chiral anomaly with nonlocal transport in three-dimensional topological semimetals. Phys. Rev. X 4, 031035 (2014).

Xiong, J. et al. Evidence for the chiral anomaly in the Dirac semimetal Na3Bi. Science 350, 413–416 (2015).

Zhang, C. et al. Signatures of the Adler–Bell–Jackiw chiral anomaly in a Weyl semimetal. Nat. Commun. 7, 10735 (2016).

Huang, X. et al. Observation of the chiral anomaly induced negative magneto-resistance in 3D Weyl semi-metal TaAs. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031023 (2015).

Chan, C.-K., Lindner, N. H., Refael, G. & Lee, P. A. Photocurrents in Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 95, 041104 (2017).

Taguchi, K., Imaeda, T., Sato, M. & Tanaka, Y. Photovoltaic chiral magnetic effect in Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 93, 201202(R) (2016).

Ishizuka, H., Hayata, T., Ueda, M. & Nagaosa, N. Emergent electromagnetic induction and adiabatic charge pumping in Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 216601 (2016).

Morimoto, T., Zhong, S., Orenstein, J. & Moore, J. E. Semiclassical theory of nonlinear magneto-optical responses with applications to topological Dirac/Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 94, 245121 (2016).

de Juan, F., Grushin, A. G., Morimoto, T. & Moore, J. E. Quantized circular photogalvanic effect in Weyl semimetals. Preprint at http://arXiv.org/abs/1611.05887 (2016).

Sodemann, I. & Fu, L. Quantum nonlinear Hall effect induced by Berry curvature dipole in time-reversal invariant materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 216806 (2015).

Chan, C.-K., Lee, P. A., Burch, K. S., Han, J. H. & Ran, Y. When chiral photons meet chiral fermions: photoinduced anomalous Hall effects in Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 026805 (2016).

Chen, Y., Wu, S. & Burkov, A. A. Axion response in Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 88, 125105 (2013).

Hosur, P. & Qi, X.-L. Tunable circular dichroism due to the chiral anomaly in Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 91, 081106(R) (2015).

Goswami, P., Sharma, G. & Tewari, S. Optical activity as a test for dynamic chiral magnetic effect of Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 92, 161110(R) (2015).

Ma, K. & Pesin, D. A. Chiral magnetic effect and natural optical activity in (Weyl) metals. Phys. Rev. B 92, 235205 (2015).

Xu, X. et al. Spin and pseudospins in layered transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Phys. 10, 343–350 (2014).

Mak, K.-F. & Shan, J. Photonics and optoelectronics of 2D semiconductor transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Photon. 10, 216–226 (2016).

Zheng, H. et al. Atomic scale visualization of quantum interference on a Weyl semimetal surface by scanning tunneling microscopy/spectroscopy. ACS Nano 10, 1378–1385 (2016).

Inoue, H. et al. Quasiparticle interference of the Fermi arcs and surface-bulk connectivity of Weyl semimetals. Science 351, 1184–1187 (2016).

Batabyal, R. et al. Visualizing ‘Fermi arc’ in the Weyl semimetal TaAs. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600709 (2016).

Yu, R. et al. Determine the chirality of Weyl fermions from the circular dichroism spectra of time-dependent angle-resolved photoemission. Phys. Rev. B 93, 205133 (2016).

Xu, B. et al. Optical spectroscopy of the Weyl semimetal TaAs. Phys. Rev. B 93, 121110(R) (2016).

Wu, L. et al. Giant anisotropic nonlinear optical response in transition metal monopnictide Weyl semimetals. Nat. Phys. 13, 350–355 (2017).

McIver, J. W. et al. Control over topological insulator photocurrents with light polarization. Nat. Nanotech. 7, 96–100 (2012).

Yuan, H. et al. Generation and electric control of spin-valleycoupled circular photogalvanic current in WSe2 . Nat. Nanotech. 9, 851–857 (2014).

Ivchenko, E. L. & Ganichev, S. in Spin Physics in Semiconductors (ed. Dyakonov, M. I.) (Springer, 2008).

Ganichev, S. D. & Prettl, W. Spin photocurrents in quantum wells. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 15, R935–R983 (2003).

Diehl, H. et al. Spin photocurrents in (110)-grown quantum well structures. New J. Phys. 9, 349 (2007).

Gabor, N. M. et al. Hot carrier assisted intrinsic photoresponse in graphene. Science 334, 648–652 (2011).

Herring, P. K. et al. Photoresponse of an electrically tunable ambipolar graphene infrared thermocouple. Nano Lett. 14, 901–907 (2014).

Murray, J. J. et al. Phase relationships and thermodynamics of refractory metal pnictides: the metal-rich tantalum arsenides. J. Less-Common Met. 46, 311–320 (1976).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Ye and J. Checkelsky for the help with sample preparation. N.G. and S.-Y.X. acknowledge support from US Department of Energy, BES DMSE, Award number DE-FG02-08ER46521 (initial planning), the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s EPiQS Initiative through Grant GBMF4540 (data analysis), and in part from the MRSEC Program of the National Science Foundation under award number DMR-1419807 (data taking, manuscript writing, and using shared experimental facilities). Work in the P.J.-H. group was partly supported by the Center for Excitonics, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Award Number DESC0001088 (fabrication and measurement) and partly through AFOSR grant FA9550-16-1-0382 (data analysis), as well as the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s EPiQS Initiative through Grant GBMF4541 to P.J.-H. P.A.L. acknowledges the support by DOE under grant DE-FG02-03-ER46076 (theoretical analyses). T.P. and Y.L. acknowledge partial funding support from the ONR PECASE project (Award No. 021302-001) and the MIT/Army Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies (Award No. 023674) (experimental setup). G.C. and H.L. were supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF), Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore, under its NRF fellowship NRF Award No. NRF-NRFF2013-03 (first-principles band structure calculations). C.-L.Z. and S.J. were supported by National Basic Research Program of China (grant Nos. 2013CB921901 and 2014CB239302) (single crystal growth). W.X. was supported by the start-up funding through LSU College of Science (single crystal XRD measurements).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.G., P.J.-H., S.-Y.X. and Q.M. designed the experiment. N.G. and P.J.-H. supervised the project. Q.M. and S.-Y.X. performed the measurements and analysed the data. Y.L. and T.P. assisted with the measurements. C.-L.Z. and S.J. grew the single crystal. G.C. and H.L. provided the first-principles band structures. C.-K.C. and P.A.L. provided theoretical analysis and calculated the photocurrents. W.X. performed the single-crystal XRD measurement. S.-Y.X. and Q.M. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary information (PDF 3211 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, Q., Xu, SY., Chan, CK. et al. Direct optical detection of Weyl fermion chirality in a topological semimetal. Nature Phys 13, 842–847 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4146

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4146

This article is cited by

-

Magnetic, transport and topological properties of Co-based shandite thin films

Communications Physics (2024)

-

Signatures of a surface spin–orbital chiral metal

Nature (2024)

-

Quantifying the photocurrent fluctuation in quantum materials by shot noise

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Defect-induced helicity dependent terahertz emission in Dirac semimetal PtTe2 thin films

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Ultrafast magnetization enhancement via the dynamic spin-filter effect of type-II Weyl nodes in a kagome ferromagnet

Nature Communications (2024)