Abstract

The efficient characterization of quantum systems1,2,3, the verification of the operations of quantum devices4,5,6 and the validation of underpinning physical models7,8,9, are central challenges for quantum technologies10,11,12 and fundamental physics13,14. The computational cost of such studies could be improved by machine learning enhanced by quantum simulators15,16. Here we interface two different quantum systems through a classical channel—a silicon-photonics quantum simulator and an electron spin in a diamond nitrogen–vacancy centre—and use the former to learn the Hamiltonian of the latter via Bayesian inference. We learn the salient Hamiltonian parameter with an uncertainty of approximately 10−5. Furthermore, an observed saturation in the learning algorithm suggests deficiencies in the underlying Hamiltonian model, which we exploit to further improve the model. We implement an interactive version of the protocol and experimentally show its ability to characterize the operation of the quantum photonic device.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In science and engineering17,18, physical systems are approximated by simplified models to allow the comprehension of their essential features. The utility of the model hinges upon the fidelity of the approximation to the actual physical system, and can be measured by the consistency of the model predictions with the real experimental data. However, predicting behaviour in the exponentially large configuration space of quantum systems is known to be intractable to classical computing machines19,20. A fundamental question therefore naturally arises: How can underpinning theoretical models of quantum systems be validated?

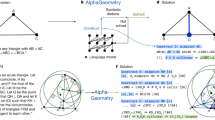

To address this question, quantum Hamiltonian learning (QHL) was recently proposed15,16 as a technique that exploits classical machine learning with quantum simulations to efficiently validate Hamiltonian models and verify the predictions of quantum systems or devices. QHL is tractable in cases in which other known methods fail because quantum simulation is exponentially faster than existing techniques19,20,21 for simulating broad classes of complex quantum systems22,23,24,25,26. Our experimental demonstration of QHL uses a digital quantum simulator20 on a programmable silicon photonic circuit, shown in Fig. 1a–c, to learn the electron spin dynamics of a negatively charged nitrogen–vacancy (NV−) centre in bulk diamond, shown in Fig. 1d, e. We further demonstrate an interactive QHL protocol that allows us to characterize and verify single-qubit gates using other trusted gates on the same quantum photonic device.

a–c, The silicon quantum photonic simulator: experimental set-up (a), quantum circuit (b), and device schematic (c). The operation, either Û or V̂, on the qubit |ψ〉, is entangled with the states, |0〉 or |1〉, respectively, of the control qubit. The device in c implements the logical circuit. A 10 mW continuous-wave pump laser with near-1,550 nm wavelength is coupled into the chip through optical fibres. In c, black lines are silicon nano-photonic waveguides (Si-WG), and gold wires represent thermo-optical (TO) phase shifters and their transmission lines. A pair of idler (blue) and signal (red) photons with different wavelengths are generated via spontaneous four-wave mixing (SFWM) in the spiral waveguide sources. These photons are split equally via multi-mode interferometer (MMI) beam splitters, producing a post-selected maximally entangled state. The operation Û or V̂ performed on idler qubit is coherently controlled by the state of the signal qubit. Performing measurements M̂ on the signal qubit allows one to estimate the likelihood function for the chosen configuration of the device. Photons are detected off-chip by fibre-coupled superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors (SNSPD). d, Confocal set-up with diamond (inset) containing NV− centres. e,f, Structure and energy level diagram, respectively, of an NV− centre in diamond. The ground-state electron spin Hamiltonian, describing the coherent dynamics between ms = 0 and −1, is to be characterized and learned using the quantum simulator in a. g, A single Rabi sequence for the initialization, manipulation and read-out of the electron spin state. A laser pulse at 532 nm is used to initialize the spin into ms = 0. Two microwave (MW) π/2-pulses with a time t delay are then used to coherently drive the spin. The spin state is measured by detecting photo-luminescence (PL) with an avalanche photodiode (APD). These two different physical systems are interfaced through a classical computer.

Silicon quantum photonics is a promising platform for the realization of manufacturable quantum technologies27,28,29,30. Our silicon device integrates entangled photon generation, projective measurements, single-qubit and two-qubit operations onto a single chip, as shown in Fig. 1c. This device implements the quantum circuit in Fig. 1b. Photons are generated and entangled in the path-encoded state  , with s and i indicating signal and idler photons29. Then the idler photon is prepared in the state |ψi〉 and undergoes an arbitrary unitary evolution,

, with s and i indicating signal and idler photons29. Then the idler photon is prepared in the state |ψi〉 and undergoes an arbitrary unitary evolution,  or

or  , conditional upon the logical state of the signal photon31. This entangled state

, conditional upon the logical state of the signal photon31. This entangled state  is realized upon the coincidental detection of the idler photon indicated by the blue dots, and the signal photon indicated by the red dots in Fig. 1c. The overlap between

is realized upon the coincidental detection of the idler photon indicated by the blue dots, and the signal photon indicated by the red dots in Fig. 1c. The overlap between  and

and  is evaluated measuring the control qubit, enabling the estimation of the likelihoods for our QHL implementations. More details on the silicon photonic device are provided in Methods and Supplementary Information 1.

is evaluated measuring the control qubit, enabling the estimation of the likelihoods for our QHL implementations. More details on the silicon photonic device are provided in Methods and Supplementary Information 1.

The solid-state spin-qubit dynamics32,33,34,35,36 under test are between the ms = 0 and ms = −1 states of the electron ground-state triplet (Fig. 1f) in the NV− centre. Optical addressing, read-out, and microwave (MW) manipulation of the electron spin are performed with a bespoke confocal microscope arrangement. At the transition frequency of 2.742 GHz, the electron spin is optically initialized into the ms = 0 state. The electron spin is then coherently driven in a single Rabi sequence (Fig. 1g), for a given evolution time t, by applying MW pulses of a fixed but arbitrarily chosen power. The photo-luminescence (PL) indicating the spin state is detected and used to obtain the output probability. For more details on NV− spin see Methods and Supplementary Information 2.

The general aim of QHL is to find the parameters x0 that best describe the dynamical Hamiltonian evolution of the system via  . Learning the Hamiltonian relies on an estimation of likelihoods, which can be exponentially hard to compute on classical machines. However, a quantum simulator can be programmed for a parametrized Hamiltonian

. Learning the Hamiltonian relies on an estimation of likelihoods, which can be exponentially hard to compute on classical machines. However, a quantum simulator can be programmed for a parametrized Hamiltonian  such that the observed data allows the efficient estimation of its associated likelihoods. The first QHL protocol we implemented is called quantum likelihood estimation (QLE). The initial state |ψ〉 of the target system is evolved for a time t and measured in a basis {|D〉}, as shown in Fig. 2a. The observed data D is fed to the quantum simulator which simulates state evolution and measurement assuming

such that the observed data allows the efficient estimation of its associated likelihoods. The first QHL protocol we implemented is called quantum likelihood estimation (QLE). The initial state |ψ〉 of the target system is evolved for a time t and measured in a basis {|D〉}, as shown in Fig. 2a. The observed data D is fed to the quantum simulator which simulates state evolution and measurement assuming  as the true Hamiltonian. Given x, the probability

as the true Hamiltonian. Given x, the probability  of obtaining D is known as the likelihood function for QLE. We then use Pr(D|x) in combination with an approximate form of Bayesian inference known as sequential Monte Carlo algorithms (SMC) to learn x and estimate its uncertainty. In this approximation, a finite set of points in the parameter space {xi}, called particles, is used to describe the probability distribution (see Methods for details).

of obtaining D is known as the likelihood function for QLE. We then use Pr(D|x) in combination with an approximate form of Bayesian inference known as sequential Monte Carlo algorithms (SMC) to learn x and estimate its uncertainty. In this approximation, a finite set of points in the parameter space {xi}, called particles, is used to describe the probability distribution (see Methods for details).

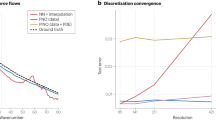

a, Schematic of QLE. The system Hamiltonian Ĥ(x0) (shaded green) is to be learned by a quantum simulator (shaded red) that embeds an abstract model Ĥ(x) of the target system. We here choose an electron spin in the NV− centre as the target system and use a silicon photonic device as the simulator. In the system, the initial state |ψ〉 is evolved for a time t and measured. The simulator mimics the system dynamics according to the model and obtains an estimate of the likelihood function using the outcomes from the system. The likelihoods are then used to infer the posterior distribution of the parameters x via Bayes’ rule and to calculate the next step time t. b, The QLE progressive learning of the electron spin Hamiltonian parametrized by a rescaled Rabi frequency ω = f/Δf. The probability distribution over Hamiltonian parameter ω is described by a discrete approximation using 20 particles. The logarithmic (rather than linear) scale of probability log(P(ω) + 1) is used to better elucidate the key information including the convergence. Within 50 steps, the distribution converges to the correct value ω0 (dashed red line). Insets: the distribution of particles after 15, 30 and 50 steps. The points represent experimental data and the shaded areas are un-normalized Gaussian fittings. c, Evolution of the mean and standard deviation of the distribution. Error bars are ±1 s.d. of the distribution. d, Evolution of the quadratic losses, here equivalent to the mean-squared errors. Circles are experimental data and the line represents theoretical simulation results with a 67.5% credible interval (shaded area). The theoretical simulation was averaged over 500 runs of QLE. e, Model validation and improvement. The presence of other physical effects in the system that are not describable by the model Ĥ(ω) (Model I) limits the amount of extractable information, as manifested by a saturation of the distribution variance at σ2(ω) ≃ 4.2 × 10−5 after approximately 35 steps. The adoption of a new two-parameter model Ĥ′(ω, α) (Model II), which includes the presence of chirping, allows one to achieve a covariance below ∥Σ∥ 2 = 7.5 × 10−6 (the shaded area). Inset: covariance norm evolution of the Model II.

Our silicon-photonics device and the NV− centre were interfaced with a classical computer, such that experimental data directly enabled QLE. Rabi oscillations of the NV− centre’s electron spin can be modelled by a Hamiltonian of the form  acting on the initial state, defining

acting on the initial state, defining  as the quantization axis (this definition is equivalent to the conventional model

as the quantization axis (this definition is equivalent to the conventional model  up to a rotation of reference frame). The silicon-photonics chip simulated the model

up to a rotation of reference frame). The silicon-photonics chip simulated the model  to learn the Rabi frequency f and to enable the calculation of the likelihood function for each particle. At each step of the QLE implementation, the evolution time t was chosen adaptively for the NV− electron spin performing a single Rabi sequence. PL results were calculated from 3 million iterations for each sequence. The likelihoods obtained were then used to update the prior distribution via the classical computer, before proceeding to the next step. The prior distribution Pr(f) of the particles was initialized to be uniform between 0 and an arbitrary value Δf, where we chose Δf = 100/2π MHz. For clarity, we consider the rescaled quantity ω = f/Δf distributed in the interval ω ∈ [0,1].

to learn the Rabi frequency f and to enable the calculation of the likelihood function for each particle. At each step of the QLE implementation, the evolution time t was chosen adaptively for the NV− electron spin performing a single Rabi sequence. PL results were calculated from 3 million iterations for each sequence. The likelihoods obtained were then used to update the prior distribution via the classical computer, before proceeding to the next step. The prior distribution Pr(f) of the particles was initialized to be uniform between 0 and an arbitrary value Δf, where we chose Δf = 100/2π MHz. For clarity, we consider the rescaled quantity ω = f/Δf distributed in the interval ω ∈ [0,1].

We performed QLE with 50 steps using a 20-particle SMC approximation to learn the electron spin dynamics of the system. Figure 2b, c show the particle distribution converging to the correct value ω0. The final learned value corresponds to the Rabi frequency fQLE = (6.93 ± 0.09) MHz, given by the mean and standard deviation of the distribution, which is consistent with the referenced value f0 = 6.90 MHz obtained with the fit of the Rabi oscillations measurements (see Supplementary Information 2). Thus the simulator successfully learns the parameter that best represents this Hamiltonian, without prior knowledge of the Rabi frequency. We note that the total number of measurements on the NV− system required for QLE is smaller than those for the fit (≃200). The fast experimental convergence of the algorithm to ω0 is observed through the evolution of the quadratic losses (here equal to the mean-squared errors) of the particle distribution achieving a final value of approximately 10−5, as shown in Fig. 2d.

Figure 2e reports the evolution of the distribution variance and shows an exponential decay in the first 35 steps. The stepping of data points, for example, near steps 15 and 24, arises from the probabilistic nature of the learning algorithm. We note that the variance σ2 saturates at approximately 4.2 × 10−5. This saturation indicates that the algorithm stops learning within this model (Model I). Such saturations are easy to spot within a Bayesian framework, because σ2 can be directly computed from the posterior distribution. This strikingly illustrates that QHL can estimate the limitations of the physical model used to describe the dynamics of the system.

Knowing when a model has failed affords us the opportunity to improve upon it. The present model was improved by introducing chirping, described by a time-dependent Hamiltonian  (Model II), where α is a chirping constant. Including chirping allows the algorithm to continue learning with an exponential decay of the covariance below ∥Σ∥2 = 7.5 × 10−6 (see Fig. 2e). The final learned values of the two parameters are fQLE = (7.00 ± 0.04) MHz and αQLE = (−0.26 ± 0.04) MHz2, which are comparable with the values f0 = 6.94 MHz and α0 = −0.28 MHz2 calculated with a full chirped Rabi fit (Supplementary Information 3). A formal comparison between the performances of the two models is given by the Bayes factor K, defined as the ratio of the average likelihoods calculated for each of the two models. Considering all of the data collected from the NV− centre in performing the algorithm, we obtain K = 560, which provides strong evidence in favour of the new model (despite its increased complexity). This demonstrates that QHL not only estimates the best model parameters, but that it also instructs us to improve the model itself, providing potentially crucial insights into underpinning physical processes. See Supplementary Information 3 for details.

(Model II), where α is a chirping constant. Including chirping allows the algorithm to continue learning with an exponential decay of the covariance below ∥Σ∥2 = 7.5 × 10−6 (see Fig. 2e). The final learned values of the two parameters are fQLE = (7.00 ± 0.04) MHz and αQLE = (−0.26 ± 0.04) MHz2, which are comparable with the values f0 = 6.94 MHz and α0 = −0.28 MHz2 calculated with a full chirped Rabi fit (Supplementary Information 3). A formal comparison between the performances of the two models is given by the Bayes factor K, defined as the ratio of the average likelihoods calculated for each of the two models. Considering all of the data collected from the NV− centre in performing the algorithm, we obtain K = 560, which provides strong evidence in favour of the new model (despite its increased complexity). This demonstrates that QHL not only estimates the best model parameters, but that it also instructs us to improve the model itself, providing potentially crucial insights into underpinning physical processes. See Supplementary Information 3 for details.

Although QLE is scalable, it often requires short evolution times to ensure the likelihood evaluation is tractable, which can preclude exponential reductions in the number of experiments needed, and makes the SMC approximation more error prone. Yet if it is possible to couple two quantum devices via a quantum (rather than a classical) channel, such as photon–NV− spin coupling systems33 or different gates on a single photonic chip10, an interactive quantum likelihood estimation (IQLE) algorithm can be adopted to overcome these problems15,16.

Similar to QLE, in IQLE the state initially evolves forward in time with the Hamiltonian of the system  . However, the transformation is then inverted by the time-reversed Hamiltonian evolution

. However, the transformation is then inverted by the time-reversed Hamiltonian evolution  , with x− sampled from the prior distribution (Fig. 3a). To ensure the backwards transformation via H−, the state must be transferred from the system to the simulator. Thus IQLE requires the presence of a coherent quantum channel between them. IQLE enables a number of significant features. It has been shown that the likelihood function for the two-outcome experiments, which involves computing

, with x− sampled from the prior distribution (Fig. 3a). To ensure the backwards transformation via H−, the state must be transferred from the system to the simulator. Thus IQLE requires the presence of a coherent quantum channel between them. IQLE enables a number of significant features. It has been shown that the likelihood function for the two-outcome experiments, which involves computing  , is efficient for

, is efficient for  even if

even if  (ref. 15). IQLE is also expected to be much more resilient to errors in the inference process, making it more robust for experimental implementations and critical device verifications16.

(ref. 15). IQLE is also expected to be much more resilient to errors in the inference process, making it more robust for experimental implementations and critical device verifications16.

a, Schematic of IQLE. The untrusted quantum system is shaded green and the trusted quantum devices are shaded red. IQLE lies in the inversion of the evolution via a Hamiltonian Ĥ(x−) implemented with a trusted device (top one). The trusted and the untrusted devices are linked by a coherent quantum channel (Q-ch). The inversion is performed also in the likelihood estimation on the trust quantum devices (bottom ones). Results are classically processed for Bayesian inference. b, Evolution of the mean and standard deviation of the distribution of the rescaled frequency ω, while IQLE is converging to the expected value of the ω0 (dashed red line). The determining of ω0 is equivalent to the characterizing of  -rotation. The sudden change in behaviour of points between the steps 8 and 15 indicates an interesting feature: the algorithm is resilient to errors from experimental noises, resuming the learning process after noisy steps. Error bars are ±1 s.d. of the distribution. c, Exponential decrease of quadratic loss for IQLE. Experimental data are shown as circles, and theoretical simulation data are shown as a line with a 67.5% credible interval (shaded area). The theoretical simulation was averaged over 500 runs of IQLE.

-rotation. The sudden change in behaviour of points between the steps 8 and 15 indicates an interesting feature: the algorithm is resilient to errors from experimental noises, resuming the learning process after noisy steps. Error bars are ±1 s.d. of the distribution. c, Exponential decrease of quadratic loss for IQLE. Experimental data are shown as circles, and theoretical simulation data are shown as a line with a 67.5% credible interval (shaded area). The theoretical simulation was averaged over 500 runs of IQLE.

Although establishing a coherent link between two distinct quantum systems is challenging29,34, such a channel naturally exists on a single quantum device10. In this case, IQLE can be applied to use calibrated gates to efficiently characterize other uncalibrated gates on the same quantum device, which now respectively represent the trusted hardware and the untrusted system to be validated. This application illustrates how IQLE could be implemented to use small trusted quantum circuits to characterize and verify large quantum circuits, improving the scalability in many-qubit systems in which characterization will be a key challenge.

We implement IQLE entirely on the single photonic chip, showing its ability to characterize single-qubit operations of quantum devices. In our experiment the photonic device plays the role of both the untrusted system and the trusted hardware, which is relevantly equivalent to the case that integrates two of the devices on a single chip. This further allows a natural implementation of a quantum device self-verification by demonstrating the algorithm, widening the context of quantum characterization and verification. The operation to be characterized here is  , where f0 matches the value of the fitted Rabi frequency, chosen for consistency with the previous QLE demonstration. Thus characterizing this

, where f0 matches the value of the fitted Rabi frequency, chosen for consistency with the previous QLE demonstration. Thus characterizing this  -rotation operation is equivalent to learning the Rabi frequency. Similar to the QLE demonstration, the Hamiltonian

-rotation operation is equivalent to learning the Rabi frequency. Similar to the QLE demonstration, the Hamiltonian  of Model I was simulated to learn the parameter ω = f/Δf. In each step of IQLE, the experiment was implemented twice: once for measuring the outcomes from the untrusted

of Model I was simulated to learn the parameter ω = f/Δf. In each step of IQLE, the experiment was implemented twice: once for measuring the outcomes from the untrusted  -rotation (top part in Fig. 3a), and once for estimating the likelihoods (bottom part in Fig. 3a). See Methods for more details. Figure 3b shows the experimental results for the estimated ω as given by the posterior mean and standard deviation at each step of IQLE. The particle distribution converges quickly to the correct value ω0. After 50 algorithm steps we obtain fIQLE = (6.92 ± 0.08) MHz, which is within 1 s.d. of the implemented Rabi frequency f0 = 6.90 MHz. The evolution of the quadratic losses (Fig. 3c) indicates that the parameter is learned exponentially fast, with a final quadratic loss value of approximately 10−7. The convergence of the algorithm to the implemented value ω0 indicates the successful self-verification of the quantum device.

-rotation (top part in Fig. 3a), and once for estimating the likelihoods (bottom part in Fig. 3a). See Methods for more details. Figure 3b shows the experimental results for the estimated ω as given by the posterior mean and standard deviation at each step of IQLE. The particle distribution converges quickly to the correct value ω0. After 50 algorithm steps we obtain fIQLE = (6.92 ± 0.08) MHz, which is within 1 s.d. of the implemented Rabi frequency f0 = 6.90 MHz. The evolution of the quadratic losses (Fig. 3c) indicates that the parameter is learned exponentially fast, with a final quadratic loss value of approximately 10−7. The convergence of the algorithm to the implemented value ω0 indicates the successful self-verification of the quantum device.

We report the first demonstration of QHL showing the capability of validating Hamiltonian models and verifying quantum devices. While these experiments use a digital quantum photonic simulator for the demonstration, QHL is universal and can be implemented on any quantum computing platform (for example, refs 10,11,12). Furthermore, this learning protocol applies to non-digital simulators, which is particularly of interest when certain classes of analogue quantum simulations are likely to approach a regime beyond that available to classical supercomputers in the medium term7,8. With anticipated future developments in quantum hardware, the QHL protocol can be scaled up to learn more complex Hamiltonians, and promises the early delivery of quantum-enhanced computational techniques to efficiently characterize and verify quantum systems and technologies, and to investigate foundational physics.

Methods

Diamond NV− centre sample and set-up.

The bulk diamond hosting the negative changed NV− centre is a chemical vapour deposition (CVD) grown sample (electronic grade) with a natural abundance of 1 ppb nitrogen impurities (see inset in Fig. 1d). The NV− centre was positioned in the static magnetic field at room temperature. All the measurements were performed on a home-built scanning confocal microscope, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. With the help of optical detected magnetic resonance (ODMR), we perfectly aligned a small external magnetic field of 5 mT in the direction of the NV− centre’s axis, lifting the degenerated ms = ±1 spin states. Supplementary Fig. 3a shows the ODMR of the NV− centre used in the experiment, which was scanned under continuous optical laser and microwave (MW) excitation, indicating the transition from ms = 0 to ms = −1 at a frequency of 2.742 GHz. More details on the confocal set-up and spin measurement are reported in Supplementary Information 2.

Silicon quantum photonic device and set-up.

The quantum device was manufactured on a standard silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafer using 248 nm-ultraviolet photolithography and reactive-ion etching. Single photons were generated and guided in silicon waveguides with a cross-section of 450 nm × 220 nm. The single-photon-pair sources were designed with a 1.2 cm length. The relative phase between different paths was manipulated using thermo-optical (TO) phase shifters obtained by metal deposition of titanium upon the silicon waveguides. Multi-mode interferometer (MMI) couplers with a size of 2.8 μm × 28 μm were used as beam splitters with a near-0.5 reflectivity. The crossers in the device showed a −40 dB crosstalk between the two intersected waveguides. The schematics of components are shown in Fig. 1c.

The chip was optically accessed via single-mode optical fibres using spot-size converters. The chip was wired-bounded on a PCB and each phase-shifter was individually controlled by an electronic driver with 12 bits resolution. Photons were detected using superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors. A classical computer was used to process the photon statistics obtained through a time interval analyser from the quantum device, and perform the Bayesian inference to update the Hamiltonian model. The detailed experimental set-up for the quantum chip is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1.

State evolution on the quantum photonic device.

The schematic of the photonic device is provided in Fig. 1c. The state generated by the SFWM sources37, is given by  in the Fock basis27. After the first pair of MMIs which here works as a probabilistic filter, the state becomes

in the Fock basis27. After the first pair of MMIs which here works as a probabilistic filter, the state becomes  by post-selecting photons29, where the number indicates the photon number occupying in different spatial modes. We re-label the top and last mode as the first two—that is, applying the following transformation |a, b, c, d〉 → |a, d, b, c〉, which is physically realized using waveguide crossers. Then, the state evolves into a maximally two-qubits entangled state.

by post-selecting photons29, where the number indicates the photon number occupying in different spatial modes. We re-label the top and last mode as the first two—that is, applying the following transformation |a, b, c, d〉 → |a, d, b, c〉, which is physically realized using waveguide crossers. Then, the state evolves into a maximally two-qubits entangled state.

If we convert the Fock state to the logic state via |0〉logic ↔ |10〉Fock (|1〉logic ↔ |01〉Fock), we obtain  , where the subscripts denote the qubit 1 and qubit 3. By adding two additional modes in the bottom paths (expanding into a four-dimensional space) which can be represented as the addition of another qubit 2, we can obtain a state equivalent to

, where the subscripts denote the qubit 1 and qubit 3. By adding two additional modes in the bottom paths (expanding into a four-dimensional space) which can be represented as the addition of another qubit 2, we can obtain a state equivalent to  . The same input state |ψ〉2 can be prepared in the higher-dimensional space. Evolving the state |ψ〉2 using two different unitaries

. The same input state |ψ〉2 can be prepared in the higher-dimensional space. Evolving the state |ψ〉2 using two different unitaries  in the upper path and

in the upper path and  in the lower path, we have the state as

in the lower path, we have the state as

Then crossing the waveguides again and interfering photons at the last two MMIs, it allows us to erase the path information between the upper and the lower path—that is, whether the photon went through the  or the

or the  operation. This is equivalent to applying a Hadamard gate to the third qubit. The state emerging by this evolution can be described as

operation. This is equivalent to applying a Hadamard gate to the third qubit. The state emerging by this evolution can be described as

Applying a post-selection for those cases where the second photon emerges from one of the upper modes—that is, projecting the third qubit into the state |0〉3—it is possible to achieve the desired state

In our QHL experiments, we choose |ψ〉2 as |0〉, which can be naturally realized after the stage of generating entangled photon state, with no compilation between the operation of unitaries and the preparation of |ψ〉2. Thus, the operations  and

and  are solely used to represent the Hamiltonian evolution.

are solely used to represent the Hamiltonian evolution.

We remark that the operation, either  or

or  , performed on the second qubit on the initial state |ψ〉2 is determined by the state of the first qubit31. This allows us to achieve the desired superposition of quantum operations. Measuring the first qubit on the

, performed on the second qubit on the initial state |ψ〉2 is determined by the state of the first qubit31. This allows us to achieve the desired superposition of quantum operations. Measuring the first qubit on the  and

and  projective basis, we can directly estimate the overlap between the states evolved according to the

projective basis, we can directly estimate the overlap between the states evolved according to the  and

and  operations. This method can be seen as an entanglement-based scheme for calculating the overlap38,39. Unfortunately we point out that the probabilistic and post-selected nature of this approach makes it not scalable, but it allows flexibility to perform likelihoods estimation in our demonstration. The details on likelihood estimation are discussed in the last section in Methods.

operations. This method can be seen as an entanglement-based scheme for calculating the overlap38,39. Unfortunately we point out that the probabilistic and post-selected nature of this approach makes it not scalable, but it allows flexibility to perform likelihoods estimation in our demonstration. The details on likelihood estimation are discussed in the last section in Methods.

Bayesian inference and Hamiltonian learning.

Bayesian inference is a commonly used method in physics and statistics for model estimation. The method is fundamentally based on the Bayes’ theorem, which gives the proper way to update a probability distribution given evidence. The fundamental object in Bayesian inference is called a prior distribution Pr(x). From a Bayesian perspective, the prior distribution describes the subjective beliefs that an experimenter may have about the model in question which is parametrized by  . For example, if we want to learn a Rabi frequency we may know from prior knowledge that f = 6.9 ± 0.01 MHz. If that is the case then a reasonable prior distribution for describing this is to take x = [f] and

. For example, if we want to learn a Rabi frequency we may know from prior knowledge that f = 6.9 ± 0.01 MHz. If that is the case then a reasonable prior distribution for describing this is to take x = [f] and

A major advantage of this approach is a posterior distribution not only gives an estimate of the most likely outcome, argmax(Pr(x)), but also gives an estimate in the uncertainty of that estimate in the form of the covariance matrix of Pr(x). We use this feature in the main body for model selection.

While the subjectivity of the initial prior distribution is a hotly debated subject among statisticians, the use of priors does an excellent job here, addressing the fact that we almost always start experiments with prior understanding of the system in question. The Bayesian formalism gives us a language to articulate it. Also the Bernstein–von Mises theorem shows that, under relatively generic assumptions, a poor choice of the prior distribution does not affect the ultimate conclusions reached by Bayesian inference. Rather it affects only the time required to learn the model in question.

The next most important object in Bayesian inference is the likelihood function. The likelihood function takes an experimental datum, D, and parameters x and outputs the probability that x generates the observed data. This is expressed as Pr(D |x) and is essential for most applications of Bayesian inference because it allows Bayes’ theorem to update the prior distribution given an observed datum:

The output of Bayes’ theorem, Pr(x|D), is known as the posterior distribution. It represents how the experimentalists’ beliefs about the model should be distributed after observing the evidence given their prior beliefs.

This update process is seldom efficient in Bayesian inference. This is because, unless there is a special relationship between the prior and the likelihood function (that is, conjugate priors), there will not be a simple analytic form for the posterior distribution. This means that the entire function must be stored in memory, which is not possible for continuous models. Such problems are often solved by using approximate inference methods.

Sequential Monte Carlo (SMC) algorithms are a class of approximate inference algorithms that are increasingly popular for approximating Bayesian inference. The idea behind these methods is to approximate the probability density by a discrete sum of points, known as particles. In particular, we wish to find a set of weights wi and positions xi such that Pr(x) ≈ ∑ iwiδ(x − xi) and ∑ iwi = 1. This allows us to replace the integrals with a sum and further allow the density to be represented in a finite amount of memory. Formally this approximation is not known to be efficient, in that the number of particles needed can be shown to scale at most sub-exponentially (rather than polynomially) with the number of model parameters. In practice, the dependence on the number of model parameters is often quite weak and often depends more strongly on the properties of the likelihood function than the size of the model.

An important technical issue about SMC algorithms is that the particles often need to move as the inference algorithm proceeds. To see this, consider the Rabi model. If we assume that the system has no noise then the Rabi frequency can be learned with infinite precision. This corresponds to a probability density of Pr(x) = δ(ω − ωtrue). This density can be described exactly inside the SMC formalism only if there is a particle xj = ωtrue. If a finite number of particles is chosen then the probability of this is zero. Therefore, to model very narrow distributions that will occur in Bayesian inference we need to move particles.

One procedure for doing this is known as resampling. The goal of the resampler is to effectively move the particles by redrawing them from a distribution that resembles the current distribution. These ‘resampled’ particles are then assigned equal weight and the learning process is resumed, now with more particles concentrated in the important parts of the posterior distribution. This resampling is triggered when the number of ‘effective’ particles in the approximation becomes too small. In particular, we resample if and when the inverse participation ratio, 1/∑ iwi2, becomes too small (usually 1/∑ iwi2 ≤ Npart/2 is taken to be the threshold). The resampler we use was given by Liu and West40 and it has the property of preserving the first two moments of Pr(x) while approximately maintaining the structure of the particle cloud.

If we specialize to the problem of QLE and IQLE experiments then our likelihood function is always of the form15,16

for QLE or

for IQLE.

An important question to ask is: ‘how do we choose t to best estimate H(x)?’ We employ an adaptive strategy known as the particle guess heuristic to provide near-optimal experiments41,42. This strategy takes the evolution time to scale as the reciprocal of the current uncertainty. For the application using QLE to estimate Rabi frequencies, we adopt a near-optimal choice of the evolution time t = 1.26/σ, where σ is the standard deviation (s.d.) of Pr(x). For IQLE, we adopt the following heuristic  , with both x1 and x− sampled from the prior distribution Pr(x) (ref. 15). Pseudocodes for both QLE and IQLE algorithms are reported in Supplementary Algorithms 1–5.

, with both x1 and x− sampled from the prior distribution Pr(x) (ref. 15). Pseudocodes for both QLE and IQLE algorithms are reported in Supplementary Algorithms 1–5.

Estimation of the likelihoods on the photonic chip.

The likelihood estimation for QLE requires the inner product between the evolved state  and the state |D〉. In this work we have used |D〉 = |ψ〉 = |0〉, in the chosen computational basis state of both NV centre and photonic device. The NV spin’s reference frame we use, defining the

and the state |D〉. In this work we have used |D〉 = |ψ〉 = |0〉, in the chosen computational basis state of both NV centre and photonic device. The NV spin’s reference frame we use, defining the  as the quantization axis, is obtained by a rotation of basis from the standard reference frame, where the quantization axis is the

as the quantization axis, is obtained by a rotation of basis from the standard reference frame, where the quantization axis is the  axis. The choice of this reference frame is due to the ease of preparing the input state |ψ〉 as |0〉 in the photonic chip, with no needs of compilation between state preparation and unitary operations (see the state evolution section in Methods).

axis. The choice of this reference frame is due to the ease of preparing the input state |ψ〉 as |0〉 in the photonic chip, with no needs of compilation between state preparation and unitary operations (see the state evolution section in Methods).

To calculate the inner product in our photonic device we exploit an entanglement-based technique38,39. The scheme realized in the integrated device allows us to produce entangled states  , where the subscripts s and i now represent the qubits 1 and 2 (see equation (4)) encoded in the signal and idler photons, respectively. When performing a projective measurement on the

, where the subscripts s and i now represent the qubits 1 and 2 (see equation (4)) encoded in the signal and idler photons, respectively. When performing a projective measurement on the  eigenbasis {|+〉, |−〉} of the signal qubit, where

eigenbasis {|+〉, |−〉} of the signal qubit, where  , we obtain

, we obtain

where p+ is the probability to get the outcome |+ 〉. Similarly, when performing a projective measurement on the  eigenbasis {|+ i〉, |− i〉}, where

eigenbasis {|+ i〉, |− i〉}, where  , we obtain

, we obtain

where p+i is the probability to get the outcome |+ i〉. The likelihood for QLE is given by  and particularly

and particularly  in this experimental demonstration, which can be easily obtained setting

in this experimental demonstration, which can be easily obtained setting

The schematic in Fig. 2a shows the QLE implementations on the photonic device. Using equations (9) and (10), we have

The values of p+ and p+i are calculated by performing the single-qubit operations on the control qubit and measuring photon coincidences.

For IQLE the likelihood  is obtained similarly using equation (12) but setting

is obtained similarly using equation (12) but setting

given the same format of Hamiltonians and evolved state |ψ〉. The schematic in Fig. 3a shows the IQLE implementations on the photonic device. The quantum channel required for IQLE in our case is thus given by the entanglement generated in the sources. We remark that using this scheme to implement IQLE all evolutions are forward in time, in contrast with the original approach where the time reversal  is performed by a backwards evolution in time15. This can make our entanglement-based approach amenable for analogue quantum simulators. However, it comes at the cost of additional entanglement between the system and an ancillary qubit.

is performed by a backwards evolution in time15. This can make our entanglement-based approach amenable for analogue quantum simulators. However, it comes at the cost of additional entanglement between the system and an ancillary qubit.

Data availability.

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional Information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Cramer, M. et al. Efficient quantum state tomography. Nat. Commun. 1, 149 (2010).

da Silva, M. P., Landon-Cardinal, O. & Poulin, D. Practical characterization of quantum devices without tomography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 210404 (2011).

Spagnolo, N. et al. Learning an unknown transformation via a genetic approach. Preprint at http://arXiv.org/abs/1610.03291 (2016).

Spagnolo, N. et al. Experimental validation of photonic boson sampling. Nat. Photon. 8, 615–620 (2014).

Carolan, J. et al. On the experimental verification of quantum complexity in linear optics. Nat. Photon. 8, 621–626 (2014).

Barz, S., Fitzsimons, J. F., Kashefi, E. & Walther, P. Experimental verification of quantum computation. Nat. Phys. 9, 727–731 (2013).

Parsons, M. F. et al. Site-resolved measurement of the spin-correlation function in the Fermi–Hubbard model. Science 353, 1253–1256 (2016).

Labuhn, H. et al. Tunable two-dimensional arrays of single Rydberg atoms for realizing quantum Ising models. Nature 53, 667–670 (2016).

Barends, R. et al. Digital quantum simulation of fermionic models with a superconducting circuit. Nat. Commun. 6, 7654 (2015).

Carolan, J. et al. Universal linear optics. Science 349, 711–716 (2015).

Debnath, S. et al. Demonstration of a small programmable quantum computer with atomic qubits. Nature 536, 63–66 (2016).

Barends, R. et al. Superconducting quantum circuits at the surface code threshold for fault tolerance. Nature 508, 500–503 (2014).

Shadbolt, P., Mathews, J. C. F., Laing, A. & O’Brien, J. L. Testing foundations of quantum mechanics with photons. Nat. Phys. 10, 278–286 (2014).

Arndt, M. & Hornberger, K. Testing the limits of quantum mechanical superpositions. Nat. Phys. 10, 271–277 (2014).

Wiebe, N., Granade, C., Ferrie, C. & Cory, D. G. Hamiltonian learning and certification using quantum resources. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 190501 (2014).

Wiebe, N., Granade, C., Ferrie, C. & Cory, D. G. Quantum Hamiltonian learning using imperfect quantum resources. Phys. Rev. A 89, 042314 (2014).

Williams, D. B. & Carter, C. B. The Transmission Electron Microscope (Springer, 1996).

Zewail, A. H. Femtochemistry: atomic-scale dynamics of the chemical bond. J. Phys. Chem. A 104, 5660–5694 (2000).

Feynman, R. P. Simulating physics with computers. Int. J. Theor. Phys. Theor. Phys. 21, 467–488 (1982).

Lloyd, S. Universal quantum simulators. Science 273, 1073–1078 (1996).

Aspuru-Guzik, A., Dutoi, A. D., Love, P. J. & Head-Gordon, M. Simulated quantum computation of molecular energies. Science 309, 1704–1707 (2005).

Kim, K. et al. Quantum simulation of frustrated Ising spins with trapped ions. Nature 465, 590–593 (2010).

Peruzzo, A. et al. A variational eigenvalue solver on a photonic quantum processor. Nat. Commun. 5, 4213 (2014).

Lanyon, B. P. et al. Towards quantum chemistry on a quantum computer. Nat. Chem. 2, 106–111 (2010).

O’Malley, P. J. J. et al. Scalable quantum simulation of molecular energies. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031007 (2016).

Salathé, Y. et al. Digital quantum simulation of spin models with circuit quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. X 5, 021027 (2015).

Bonneau, D., Silverstone, J. W. & Thompson, M. G. Silicon Photonics III (eds Pavesi, L. & Lockwood, D. J.) 41–82 (Springer, 2016).

Silverstone, J. W. et al. Qubit entanglement between ring-resonator photon-pair sources on a silicon chip. Nat. Commun. 6, 7948 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Chip-to-chip quantum photonic interconnect by path-polarization interconversion. Optica 3, 407–413 (2016).

Najafi, F. et al. On-chip detection of non-classical light by scalable integration of single-photon detectors. Nat. Commun. 6, 5873 (2015).

Zhou, X. Q. et al. Adding control to arbitrary unknown quantum operations. Nat. Commun. 2, 413 (2011).

Jelezko, F., Gaebel, T., Popa, I., Gruber, A. & Wrachtrup, J. Observation of coherent oscillations in a single electron spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 076401 (2004).

Togan, E. et al. Quantum entanglement between an optical photon and a solid-state spin qubit. Nature 466, 730–734 (2010).

Bernien, H. et al. Heralded entanglement between solid-state qubits separated by three metres. Nature 497, 86–90 (2013).

Li, L. et al. Coherent spin control of a nanocavity-enhanced qubit in diamond. Nat. Commun. 6, 6173 (2015).

Chen, Y. C. et al. Laser writing of coherent colour centres in diamond. Nat. Photon. 11, 77–80 (2017).

Sharping, J. E. et al. Generation of correlated photons in nanoscale silicon waveguides. Opt. Exp. 14, 12388–12393 (2006).

Buhrman, H., Cleve, R., Watrous, J. & de Wolf, R. Quantum finger-printing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 167902 (2001).

Cai, X. D. et al. Entanglement-based machine learning on a quantum computer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 110504 (2015).

Liu, J. & West, M. Statistics for Engineering and Information Science (eds Doucet, A., Freitas, N. & Gordon, N.) 225–246 (Springer, 2001).

Ferrie, C., Granade, C. & Cory, D. G. How to best sample a periodic probability distribution, or on the accuracy of Hamiltonian finding strategies. Quantum Inf. Process. 12, 611–623 (2013).

Wiebe, N. & Granade, C. Efficient Bayesian phase estimation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 010503 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. W. Silverstone, D. Bonneau, X. Zhou, D. P. Tew, J. Carolan, S. Jia and C. Granade for useful discussions. We thank K. Ohira, N. Suzuki, H. Yoshida, N. Iizuka and M. Ezaki for the device fabrication. We acknowledge the support from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), European Research Council (ERC), Photonic Integrated Compound Quantum Encoding (PICQUE), Beyond the Barriers of Optical Integration (BBOI), Quantum Simulation on a Photonic Chip (QuChip), and Wavelength-tunable Advanced Single Photon Sources (WASPS), US Army Research Office (ARO), and the Centre for Nanoscience and Quantum Information (NSQI). M.P. acknowledges the support by a Short-Term Scientific Missions (STSM) Grant from European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) action MP1403. A.L. acknowledges support from an EPSRC Early Career Fellowship. J.G.R. is sponsored under EPSRC grant EP/M024458/1. J.L.O’B. acknowledges a Royal Society Wolfson Merit Award and a Royal Academy of Engineering Chair in Emerging Technologies. M.G.T. acknowledges the support from an EPSRC Early Career Fellowship and the Toshiba Research Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W., S.P., R.S., S.K. and N.W. conceived and designed the experiments. N.W. provided theoretical support. S.P. and M.P. performed the simulations. J.W., S.P., R.S., S.K. and A.A.G. built the set-ups, carried out the experiment, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with feedback from all authors. N.W., J.L.O’B., J.G.R., A.L. and M.G.T. managed the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary information (PDF 750 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Paesani, S., Santagati, R. et al. Experimental quantum Hamiltonian learning. Nature Phys 13, 551–555 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4074

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4074

This article is cited by

-

Experimental graybox quantum system identification and control

npj Quantum Information (2024)

-

Demonstration of hypergraph-state quantum information processing

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Practical Hamiltonian learning with unitary dynamics and Gibbs states

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Efficient and robust estimation of many-qubit Hamiltonians

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Quantum machine learning for support vector machine classification

Evolutionary Intelligence (2024)