Abstract

Photoemission and tunnelling spectroscopies measure the energies at which single electrons can be added to or removed from an electronic system1. Features observed in such spectra have revealed electrons coupling to vibrational modes of ions both in solids2 and in individual molecules3. Here we report the discovery of a sharp resonance in the tunnelling spectrum of a two-dimensional electron system. Its behaviour suggests that it originates from vibrational modes, not involving ionic motion, but instead arising from vibrations of spatial ordering of the electrons themselves. In a two-dimensional electronic system at very low temperatures and high magnetic fields, electrons can either condense into a variety of quantum Hall phases or arrange themselves into a highly ordered ‘Wigner’ crystal lattice4,5,6. Such spatially ordered phases of electrons are often electrically insulating and delicate, and have proven very challenging to probe with conventional methods. Using a pulsed tunnelling method capable of probing electron tunnelling into insulating phases, we observe a sharp peak with dependencies on energy and other parameters that fit to models for vibrations of a Wigner crystal7,8. The remarkable sharpness of the structure presents strong evidence of the existence of a Wigner crystal with long correlation length.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Theory suggests that a Wigner crystal (WC) may exist near integer quantum Hall states as an insulating phase with expected transition temperature in the range of a few hundred millikelvin or below5,6,9,10,11,12. Measurements in these regimes have demonstrated insulating phases13,14,15, microwave pinning resonances12,16, Knight shifts17, and compressibility features18 suggestive of a Wigner solid. However, it has proven difficult to demonstrate a long-range ordered crystal; the observed features could arise from localization of electrons or a short-range ordered glassy phase. One method of detecting crystalline order is by means of observation of the crystal’s vibrations. In prior measurements1, strong coupling of tunnelling electrons to vibrational modes of ions have given rise to ‘bosonic peaks’ in the tunnelling spectra. Observation of such structure was essential to verifying the Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer theory of superconductivity1. In this letter, we report the observation of a sharp peak in tunnelling spectra that displays the characteristics of phonons of an electron crystal.

As with a lattice formed by ions in normal materials, the WC has gapless phonon modes from transverse and longitudinal phonons. However, application of a magnetic field forces hybridizes the two modes into magnetoplasmon and magnetophonon modes7,19, with the magnetophonon mode remaining as a gapless Goldstone mode that signals the emergence of crystalline order (spontaneous translational symmetry breaking)7,8. A measurement revealing the sharp magnetophonon mode would constitute direct and conclusive evidence of the existence of the WC. In this study, we detect the presence of the magnetophonon spectrum through its modification of the tunnelling density of states (TDOS), and we control the energy scale of the magnetophonon spectrum by tuning the electronic carrier density and applied magnetic field. Our measurements rely on a pulsed tunnelling method, capable of precisely measuring the TDOS in both conductors and insulators20 to measure the TDOS of a two-dimensional (2D) hole system under high perpendicular magnetic fields (see the caption of Fig. 1 and Methods for further details).

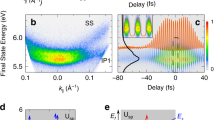

a, Schematics of a vertical tunnelling device. The sample is a 150-μm-diameter isolated mesa made of a GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructure 14-nm-wide quantum well (QW) sandwiched between two heavily doped metallic electrodes by a tunnelling and an insulating barrier. A strongly correlated 2D electronic system in a QW (red) is probed by tunnelling from the top electrode (silver). The bias voltage Vb controls the density by drawing charge capacitively into the QW. The amplitude of an applied voltage pulse multiplied by the geometric lever arm determines the tunnelling voltage Vt (see Methods). We determine the tunnelling current I by measuring the charge displacement using high-frequency high electron mobility transfer (HEMT) amplifiers. b, Tunnelling density of states (dI/dVt) as a function of tunnelling energy Et = (−e)Vt and carrier filling factor ν (= n2Dh/eB, where n2D is the particle density of 2D system, h is the Planck constant and e is the electron charge) of a hole-doped GaAs QW at B = 8 T and T = 25 mK. Tunnelling energies are relative to the Fermi level (Et = 0) of the system, and injection (ejection) in the spectrum is positive (negative) energy. The resonance in tunnelling appears as the sharp U-shaped features inside the yellow box. c, A zoomed-in view around ν = 1 is shown displaying the antisymmetric structure of the resonances. d, Upper panel: Vertical line cuts measured at 25 mK (magenta) and 250 mK (black) at ν = 0.86, the location shown by red arrows in b. Lower panel: Normalized TDOS obtained by [TDOS(25 mK) − TDOS(250 mK)]/TDOS(250 mK). Antisymmetric resonance features (dotted circles) are clearly visible. e,f, The same spectra as in b,c, respectively, with a slowly varying background subtracted to reveal fine structures of the data. The feature inside the white box shows another resonance feature near ν = 0 (see also Supplementary Section 8). In f, the orange arrow indicates the energy offset between the resonance feature in positive and negative bias (see Supplementary Section 5). The yellow arrows point to the vertical noise line discussed in the main text.

The TDOS of a hole-doped quantum well (QW) measured at B = 8 T and T = 25 mK are shown in Fig. 1b. In addition to the general spectral structure reported previously20,21, these lower-temperature measurements reveal very sharp resonances around the filling factor ν = 1, whose full width is about 0.2 meV. The resonances display an antisymmetry around the Fermi level and filling factor ν = 1 (see Fig. 1c, f); that is, for ν < 1 (ν > 1) the tunnelling conductance peaks (dips) for energies greater than the Fermi level and dips (peaks) for energies below the Fermi level.

We examine scenarios to explain this signal. First of all, the observation of the low-energy resonance signals in tunnelling near ν = 1 may suggest an origin in spin-related excitations due to skyrmions22,23. However, while the strongest resonances in our spectrum appear near ν = 1, we also see resonances with nearly identical energies and dispersions near ν ∼ 0 and ν ∼ 2 (see Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 12 of Supplementary Section 8). To our knowledge, there has been no proposal so far for spin-related excitations near filling factors 0 and 2. Secondly, we rule out disorder-induced localization and oscillations of locally trapped particles due to the observed sharpness of the resonance and because these modes should soften due to screening as the quasiparticle density increases, in contrast to our observation.

It thus seems reasonable to focus on a possible electron–phonon interaction in the system. Tunnelling studies show that, in metals and semiconductors, phonons can strongly couple to electrons and display resonances in electron tunnelling spectrum1. While it is well known that tunnelling electrons that inelastically scatter phonons can generate an increase in tunnelling conductance symmetrically in bias voltage around the Fermi level, an antisymmetric feature in the TDOS can arise from elastic coupling of electrons to the phonon degrees of freedom1,2,24. Formally speaking, the electron–phonon interaction generates a non-zero self-energy Σ of tunnelling electrons, whose antisymmetric real part is strongly peaked at the energy of the van Hove singularity εvH. The self-energy can be interpreted as an additional complex-valued potential existing only at an energy near ±εvH that modulates the tunnelling matrix element and the TDOS (see Fig. 1d and Supplementary Section 1).

The emergence of these features arising from an electron–phonon interaction in the TDOS appears surprising because no strong ionic phonon DOS exists in the energy scale of a few meV—the charged carriers in this system are effectively decoupled from ionic lattice dynamics. More importantly, the resonance energy εr in the spectrum is a strong function of filling factor ν, pointing to the electron–electron interaction as the origin of the feature. These observations lead us to consider that the phonons generated from ordered states of electrons themselves affect the tunnelling spectrum. In Landau levels, the existence of robust energy gaps around integer filling factors permits a description in terms of quantum Hall quasiparticles; a system with an integer filling factor ν = l (with l = 0, 1, 2, …) contains l ‘inert’ filled (spin-resolved) Landau levels, and as the filling factor ν is tuned away from integer values, the added or subtracted particles can be described as quasiparticles of effective filling factor νqp = |l − ν|. When νqp is small, these quasiparticles resemble bare electrons and holes with Coulombic interactions that may lead to the formation of a WC6,9.

To examine this idea quantitatively, we explore the hypothesis that the spectrum of the resonance feature near ν = 1, at low effective quasiparticle filling factor νpq = |1 − ν|, follows the energy scaling law of the magnetophonon of a WC formed by quantum Hall quasiparticles7,8 (see Fig. 2). In this picture, the strong resonance at εr in the TDOS results from the peaked DOS of the magnetophonons originating from a van Hove singularity (at εvH) near the Brillouin zone boundary of the hexagonal WC. The energy of the resonance appears to follow εr = Δ + εvH, where Δ accounts for the magnetic-field-induced Coulomb gap Δc (and a spin gap in the case of injecting or ejecting minority spins—see Supplementary Section 5) near the Fermi level20,25. Generally, in a Coulombic system we expect that the energy scale of the interaction would increase along with the effective filling factor of quasiparticles νqp = |1 − ν| as the interparticle distance ls between the quasiparticles shrinks. In the case of a crystal, as ls decreases, the energy scales of the entire phonon dispersion and of the van Hove singularity εvH increase as a result. To compare our data with theoretically expected dispersions, in Fig. 2a we have overlaid our data with semiclassical and fully quantum mechanical curves calculated for phonon energy versus filling factor. The semiclassical harmonic approximation is given by  , where lB is the magnetic length, εs is the dielectric constant,

, where lB is the magnetic length, εs is the dielectric constant,  is a dimensionless dynamic matrix whose determinant is an order of unity, and k is the phonon wavevector7,8. The van Hove singularity εvH is located at k = kM (M-point in the hexagonal Brillouin zone; see Fig. 2b) with

is a dimensionless dynamic matrix whose determinant is an order of unity, and k is the phonon wavevector7,8. The van Hove singularity εvH is located at k = kM (M-point in the hexagonal Brillouin zone; see Fig. 2b) with  (ref. 8). This semiclassical approximation applies only when the quasiparticle density is low (νqp = |1 − ν| ≪ 1). As shown in Fig. 2a, the semiclassical predictions (blue curves), after multiplication by an overall scaling factor of 1.5, fit well in the range of the filling factor 0.88 < ν < 1; however, as ls becomes smaller and νqp becomes larger, the quasiparticle wavefunctions have more overlap, and higher-order, non-harmonic, quantum mechanical effects become more important8.

(ref. 8). This semiclassical approximation applies only when the quasiparticle density is low (νqp = |1 − ν| ≪ 1). As shown in Fig. 2a, the semiclassical predictions (blue curves), after multiplication by an overall scaling factor of 1.5, fit well in the range of the filling factor 0.88 < ν < 1; however, as ls becomes smaller and νqp becomes larger, the quasiparticle wavefunctions have more overlap, and higher-order, non-harmonic, quantum mechanical effects become more important8.

a, Tunnelling density of states. The blue dashed lines are curve fits to |1 − ν|3/2 = νqp3/2 after taking account of the Coulomb gap Δc (yellow dots) near the Fermi level (see Supplementary Section 4 for details). The red dotted lines represent an additional quantum mechanical stiffening effect (see main text for discussion). b, A saddle point in the 2D dispersion relation for phonons gives rise to a van Hove singularity. The existence of this logarithmically divergent van Hove singularity is a unique feature of a 2D crystalline phase. In the 2D hexagonal Brillouin zone of a WC, it is located at the M-point (indicated by a red star). Note that the size of the Brillouin zone depends on the filling factor as  , and the overall energy scale also changes.

, and the overall energy scale also changes.

To account for this additional stiffening of the resonance, one would require the full quantum mechanical treatment. In the lowest Landau level, Chang et al. have shown that crystals described with a composite fermion (CF) wavefunction correctly account for quantum correlations and become the lowest energy state even at very low νqp (ref. 10). For comparison with data, we have plotted curves with additional quantum stiffening expected from the shear modulus of a crystal of composite fermions with four flux quanta attached11, which is shown to be the ground state below νqp ∼ 0.18 down to νqp ∼ 0.12 (see red curves in Fig. 2; see Supplementary Section 4 for more detail). The theoretical curves capture the qualitative aspect of the stiffening of the resonance that evolves as νqp increases; the nontrivial sudden increase of the stiffness in our data can be explained by the characteristic of the CF correlation near the phase transition. We also note that the short distance to the tunnelling electrode (∼35 nm from the well centre) means that the effect of screening diminishes at higher quasiparticle densities, thus further stiffening the crystal.

To investigate the nature of the observed resonance as further evidence of the magnetophonons and the quasiparticle crystal, we studied the temperature dependence (see Fig. 3). As temperature is increased from the base electron temperature (25 mK), the resonance diminishes in strength, and disappears completely above ∼200 mK. This observation agrees with previous reports of the temperature-induced disappearance of the insulating phases and pinning resonances, and is consistent with the thermal melting of a WC of quasiparticles and the resulting disappearance of its magnetophonons14,16. At 25 mK, on increasing the density of quasiparticles by changing the filling factor away from ν = 1, the resonance features terminate. This suggests that the WC undergoes another melting transition—one that is a purely density-driven quantum mechanical phase transition.

How the behaviour of the phonon energy εvH changes as the crystal melts (either via tuning ν or T) can give hints on the nature of the phase transition. For a second-order transition, theories predict that the shear modulus (and phonon frequency) would diminish to zero at the transition26; however, we observe that the magnetophonon energy εvH does not decrease towards zero in either the thermal or quantum melting transition. This strongly suggests that the phase transition is of first order, with hysteresis involved at the transition26. Although we were not able to directly measure hysteresis involved with the first-order transition, the vertical features extending from the resonances in the dI/dVt versus (Et, ν) plot (see yellow arrows in Fig. 1f) are consistent with a picture of increased measurement noise due to the presence of hysteresis at the transition (see Supplementary Section 7). According to a calculation of Maki et al. 9,26 that did not account for fractional quantum Hall (FQH) order, the shear modulus of the crystal has a peak value at νqp ≡ |ν − 1| ∼ 0.27, then decreases to zero at νqp ∼ 0.45, where the crystal would undergo a second-order phase transition to a liquid phase, in an apparent disagreement with our observation. However, as the authors noted, the crystalline phase competes with FQH liquid states. If the ground state energy of the ν = 4/5 (νqp = 1/5) FQH state is lower than that of the WC, the crystalline phase would abruptly terminate before νqp reaches 0.2, with a potentially first-order phase transition. Very interestingly, Archer et al. predict that the shear modulus would have discontinuous jumps at phase transitions11 due to correlations of CFs within the crystal. We observe that the filling factor needed for the disappearance of the phonon feature is νqp > ∼0.17, which is in rough quantitative agreement with the theory of Archer et al. and with the termination of insulating phases previously reported in transport studies and microwave pinning measurements11,14,16. We are also able to identify a weaker but clear resonance signal near ν ∼ 0 in the spectrum (see the white square in Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 12a of Supplementary Section 8) that corroborates the fact that the WC is indeed the ground state as ν → 0. It is crucial to note that we measure the internal spectrum of the crystal, distinct from transport or microwave measurements of the insulating phase that indicate localization and pinning of electrons but do not demonstrate a crystalline order.

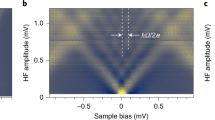

Even though we observed the resonance signals at ν = 0 and 1, there still remains a question of whether the quasiparticles near ν = 1 are comprised of skyrmions or normal QH quasiparticles because, in principle, phonon modes can exist in either case27. Skyrmions were proposed as energetically stable quasiparticles near ν = 1 in systems where the Coulomb exchange energy scale EC dominates the Zeeman energy EZ (that is, quantum Hall ferromagnet)28. Thus, some hints can be provided by measuring the electron system, where EZ/EC is tunable by external magnetic fields, that changes the nature of the particle near ν = 1. As an investigation into the possibility of the skyrme lattice27, we performed similar measurements on an electron-doped sample with and without in-plane magnetic field in an attempt to tune EZ/EC. An in-plane field is expected to shrink the size of skyrmions and, at sufficiently high in-plane fields, skyrmions will no longer be the ground state quasiparticles29. In Fig. 4a, b, we plot spectra measured, respectively, at B⊥ = 6 T, B∥ = 0 T (where EZ/EC is 0.036) and B⊥ = 5.8 T, B∥ = 8.2 T (where EZ/EC is 0.062). Thus, we expect to have small-size skyrmions for the former case and usual quasiparticles with single-spin flip for the latter case29. We observe that, when measured without an in-plane field, the magnetophonon resonance was absent around ν = 1. The application of in-plane magnetic fields creates visible resonances around ν = 1, suggesting that elimination of skyrmions in favour of ordinary quasiparticles allows observation of magnetophonon resonances in the TDOS.

a–e, TDOS as a function of energy and ν (with a smooth background subtracted; see raw data in Supplementary Fig. 14 of Supplementary Section 8) for a 2D electron sample. a,b, TDOS at 25 mK for a field of 6 T applied purely perpendicularly to the 2D layer (a) and for a perpendicular magnetic field of 5.8 T with an in-plane magnetic field of 8.2 T (b). The blue dotted circles and white rectangles indicate the resonant features that exist only at low temperature. c,d, Zoom-ins on the area inside the white rectangles in a and b, respectively. e, TDOS when the temperature is increased to 500 mK but otherwise the same as d. Note the resonant features appear only at low temperature with a large in-plane magnetic field. f, Line cuts of the normalized TDOS, obtained in the same way as in Fig. 1d using 25 mK and 500 mK data at ν = 1.08. The peaks and dips are obtained by curve fits at various ν values and overlaid on the spectra inside the white rectangles in d with blue (dips) and red (peaks) curves as shown in the insets.

Remarkably, we find that the locations of εvH of the electron system are very close to those of the hole system (within 20%), although the effective mass of the electron systems is about five times smaller. This provides strong evidence of the characteristic mass independence of the magnetophonon spectrum in the extreme quantum limit of high magnetic fields19 (see Supplementary Section 6).

The observed sharpness of the resonance features suggests well-defined phonon energies, and hence a long lattice correlation length. For the magnetophonon mode, we expect that the energy of the resonance follows εvH ∝ 1/ls3. Attributing the entire width of the observed resonance to the broadening due to lattice inhomogeneity, it leads to the relationship Δls/ls ∼ ΔεvH/3εvh. Very roughly, for the hole sample, the resonance shown in Fig. 3b gives ΔεvH/εvH ∼ 0.3, and thus Δls/ls ∼ 0.1, or a lattice correlation length of about 10 lattice spacings. In Supplementary Section 3, we obtain a better lower bound estimate of lattice correlation length by numerically simulating the electron self-energy and fitting to the data. At ν = 0.88, this calculation gives a lower bound of the correlation length Lc ∼ 15ls ∼ 970 nm. A similar calculation for the electron sample gives Lc ∼ 3ls ∼ 250 nm. We conclude by noting that this observation suggests that tunnelling spectra can probe other ordered electronic states, such as stripe and bubble phases in the quantum Hall regime30.

Methods

The measurement employs a sequence of high-frequency square pulses using a Tektronix DTG5274 pulse generator and a home-made pulse shaper which minimizes distortions of the pulses (see Supplementary Fig. 1a). The initial pulse induces a tunnelling voltage across the tunnelling barrier. Subsequently applied opposite polarity pulses are used to retrieve the tunnelled electrons out of the QW.

Using a bias-tee, we are able to apply a d.c. voltage and pulses to the samples at the same time. The d.c. voltage capacitively tunes the carrier density in the 2D system (see Supplementary Fig. 1a). As there is no leakage through the sample (the thick AlGaAs barrier prevents leakage), this d.c. voltage changes only the carrier density in the quantum well and induces no current. The filling factor (proportional to density) is calibrated precisely by independently measuring and integrating the capacitance of the samples, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1d, e.

The pulse amplitude defines the tunnelling energy of electrons; the tunnelling energy scale is given by the pulse amplitudes multiplied by the geometric lever arm of a heterostructure (the distance between QW to top electrode divided by the distance between top and bottom electrode), which is ∼0.21 for the hole wafer and ∼0.25 for the electron wafer, respectively. The pulse parameters are adjusted to ensure that the system returns to the initial equilibrium state between pulses with a predefined density of the 2D system (that is, the pulse sequence returns the system back to the same density of electrons or holes in the 2D system, with the 2D system in equilibrium with the 3D tunnelling electrode—there is also a delay of approximately 300 μs between pulses, and this allows the 2D system back down to its base temperature). The rise time of the pulses is ∼2 ns, during which only a small number of particles (due to the slow tunnelling rate in our samples—the effective RC time for equilibration is roughly on the order of 1 ms, which is about five orders of magnitude longer than the rise time) tunnel before the actual determination of tunnelling conductance starts. This amounts to a change of 104 cm−2 in electron density. The tunnelling current is determined by measuring the linear increase of the displacement charge in response to the applied initial pulse in ∼2 ms (during which the electron density change of ∼107 cm−2 can occur, less than a part per thousand of the equilibrium density) before the 2D system is disturbed. This means that the measurement of the tunnelling current accurately measures the tunnelling density of states, a true equilibrium property of the sample.

The amount of charge that tunnels in and out of the QW is measured by HEMT amplifiers at the mixing chamber, and further amplified by cryogenic Si–Ge transistors (Weinreb amplifiers) and room-temperature broadband amplifiers. All amplifiers are 50 Ω impedance-matched. The pulse sequence is repeated and averaged over 100,000 ∼ 1,000,000 times for a good signal-to-noise ratio, generating a number that represents a single pixel of data in a 2D spectrum. As positive and negative energy sides are measured separately, there exists some noise near E = 0. This noise does not affect our study, and can always be effectively suppressed by measuring with finer voltage steps. To maintain low electronic temperature in the system, we thermally anchored attenuators at 1 K and 8 mK stages and used NbTi-NbTi coaxial cables between the stages. In addition, the amplifiers are thermally decoupled from the samples by means of a resistive manganin wire (∼20 Ω) wound around an oxygen-free high-conductivity copper heat sink post (∼8 mK). Furthermore, the power dissipation of the amplifier is maintained in the range of less than a few hundred nanowatts. By measuring the strongly temperature-dependent suppression of the zero-bias tunnelling in a perpendicular magnetic field, we have confirmed that an electronic temperature of ∼25 mK (±5 mK) was achieved.

Data availability.

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wolf, E. L. Principles of Electron Tunneling Spectroscopy (Oxford Univ. Press, 2011).

Rowell, J. M., McMillan, W. L. & Feldmann, W. L. Phonon emission and self-energy effects in normal-metal tunneling. Phys. Rev. 180, 658–668 (1969).

Stipe, B. C., Rezaei, M. A. & Ho, W. Single-molecule vibrational spectroscopy and microscopy. Science 280, 1732–1735 (1998).

Wigner, E. On the interaction of electrons in metals. Phys. Rev. 46, 1002–1011 (1934).

Lozovik, Y. E. & Yudson, V. I. Crystallization of a two-dimensional electron gas in a magnetic field. JETP Lett. 22, 274–276 (1975).

Fertig, H. A. in Perspectives in Quantum Hall Effects (eds Sarma, S. D. & Pinczuk, A.) 71–108 (Wiley, 1996).

Bonsall, L. & Maradudin, A. A. Some static and dynamical properties of a two-dimensional Wigner crystal. Phys. Rev. B 15, 1959–1973 (1977).

Cǒté, R. & MacDonald, A. H. Phonons as collective modes: the case of a two-dimensional Wigner crystal in a strong magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 2662–2665 (1990).

Maki, K. & Zotos, X. Static and dynamic properties of a two-dimensional Wigner crystal in a strong magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 28, 4349–4356 (1983).

Chang, C.-C., Jeon, G. S. & Jain, J. K. Microscopic verification of topological electron-vortex binding in the lowest Landau-level crystal state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 016809 (2005).

Archer, A. C., Park, K. & Jain, J. K. Competing crystal phases in the lowest Landau level. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 146804 (2013).

Andrei, E. Y. et al. Observation of a magnetically induced Wigner solid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 2765–2768 (1988).

Jiang, H. W. et al. Quantum liquid versus electron solid around ν = 1/5 Landau-level filling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 633–636 (1990).

Goldman, V. J., Santos, M., Shayegan, M. & Cunningham, J. E. Evidence for two-dimentional quantum Wigner crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 2189–2192 (1990).

Piot, B. A. et al. Wigner crystallization in a quasi-three-dimensional electronic system. Nat. Phys. 4, 936–939 (2008).

Chen, Y. et al. Microwave resonance of the 2D Wigner crystal around integer Landau fillings. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 016801 (2003).

Tiemann, L., Rhone, T. D., Shibata, N. & Muraki, K. NMR profiling of quantum electron solids in high magnetic fields. Nat. Phys. 10, 648–652 (2014).

Zhang, D., Huang, X., Dietsche, W., von Klitzing, K. & Smet, J. H. Signatures for Wigner crystal formation in the chemical potential of a two-dimensional electron system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 076804 (2014).

Johansson, P. & Kinaret, J. M. Tunneling between two two-dimensional electron systems in a strong magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 50, 4671–4686 (1994).

Dial, O. E., Ashoori, R. C., Pfeiffer, L. N. & West, K. W. High-resolution spectroscopy of two-dimensional electron systems. Nature 448, 176–179 (2007).

Dial, O. E., Ashoori, R. C., Pfeiffer, L. N. & West, K. W. Anomalous structure in the single particle spectrum of the fractional quantum Hall effect. Nature 464, 566–570 (2010).

Gallais, Y., Yan, J., Pinczuk, A., Pfeiffer, L. N. & West, K. W. Soft spin wave near ν = 1: evidence for a magnetic instability in skyrmion systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 086806 (2008).

Gervais, G. et al. Evidence for skyrmion crystallization from NMR relaxation experiments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 196803 (2005).

Davis, L. C. & Duke, C. B. Analysis of the tunneling measurement of electronic self-energies due to interactions of electrons and holes with optical phonons in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. 184, 764–779 (1969).

Ashoori, R. C., Lebens, J. A., Bigelow, N. P. & Silsbee, R. H. Equilibrium tunneling from the 2-dimensional electron-gas in GaAs—evidence for a magnetic-field-induced energy-gap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 681–684 (1990).

Millis, A. J. & Littlewood, P. B. Radio-frequency absorption as a probe of the transition between the Wigner crystal and the fractionally quantized Hall state. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17632–17635 (1994).

Côté, R. et al. Collective excitations, NMR, and phase transitions in skyrme crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 4825–4828 (1997).

Sondhi, S. L., Karlhede, A., Kivelson, S. A. & Rezayi, E. H. Skyrmions and the crossover from the integer to fractional quantum Hall effect at small Zeeman energies. Phys. Rev. B 47, 16419–16426 (1993).

Schmeller, A., Eisenstein, J. P., Pfeiffer, L. N. & West, K. W. Evidence for skyrmions and single spin flips in the integer quantized Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 4290–4293 (1995).

Fogler, M. M., Koulakov, A. A. & Shklovskii, B. I. Ground state of a two-dimensional electron liquid in a weak magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 54, 1853–1871 (1996).

Acknowledgements

The work at MIT was funded by the BES Program of the Office of Science of the US DOE, contract no. FG02-08ER46514, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, through grant GBMF2931. The work at Princeton University was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through the EPiQS initiative Grant GBMF4420, and by the National Science Foundation MRSEC Grant DMR-1420541. We thank P. A. Lee and I. Sodemann for helpful conversations. We thank N. Staley for a careful proofreading of the manuscript and A. Demir for assistance in amplifier design.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J. and B.M.H. performed measurements. J.J. and R.C.A. analysed data. K.W.W. and L.N.P. grew GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructures. All authors discussed the results. J.J. and R.C.A. wrote the paper, and R.C.A. supervised the overall project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary information (PDF 1534 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jang, J., Hunt, B., Pfeiffer, L. et al. Sharp tunnelling resonance from the vibrations of an electronic Wigner crystal. Nature Phys 13, 340–344 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3979

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3979

This article is cited by

-

Direct observation of a magnetic-field-induced Wigner crystal

Nature (2024)

-

A highly correlated topological bubble phase of composite fermions

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Strong correlations in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2023)

-

Competing correlated states around the zero-field Wigner crystallization transition of electrons in two dimensions

Nature Materials (2022)

-

A long-sought regime of electronic behaviour

Nature Materials (2022)