Abstract

Growing evidence indicates that the superconducting pyrochlore Cd2Re2O7 exhibits a structural phase transition at Tc=200 K with an unusual tensor character1,2,3. The structural order parameter for this state is two-dimensional, and spanned by distinct but nearly degenerate crystallographic structures I4122 and  (ref. 1). Symmetry rules imply that the low-energy excitations of the ordered state are Goldstone phonons, or long wavelength fluctuations between the two crystal structures. These are the structural equivalents of magnons in an XY antiferromagnet, with the two crystal structures analogous to orthogonal spin directions in the xy-plane. Goldstone phonons have been observed in Raman spectroscopy3, but high-resolution X-ray and neutron scattering experiments have produced conflicting assignments of the static low-temperature structure4,5,6. Here, we use optical second-harmonic generation with polarization sensitivity to assign the

(ref. 1). Symmetry rules imply that the low-energy excitations of the ordered state are Goldstone phonons, or long wavelength fluctuations between the two crystal structures. These are the structural equivalents of magnons in an XY antiferromagnet, with the two crystal structures analogous to orthogonal spin directions in the xy-plane. Goldstone phonons have been observed in Raman spectroscopy3, but high-resolution X-ray and neutron scattering experiments have produced conflicting assignments of the static low-temperature structure4,5,6. Here, we use optical second-harmonic generation with polarization sensitivity to assign the  structure unambiguously and verify an auxiliary condition on the structure that is implied by the order parameter symmetry. We also show that the temperature dependence of the order parameter is consistent with thermal occupation of the Goldstone mode. The methodology may be applied more widely in characterizing ordered states in matter.

structure unambiguously and verify an auxiliary condition on the structure that is implied by the order parameter symmetry. We also show that the temperature dependence of the order parameter is consistent with thermal occupation of the Goldstone mode. The methodology may be applied more widely in characterizing ordered states in matter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

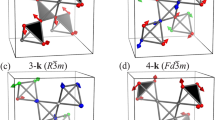

Various experimental probes show a continuous cubic-to-tetragonal transition in Cd2Re2O7 at Tc (refs 1, 2, 4–10). However, as Anderson and Blount pointed out over 40 years ago11, a less conventional order parameter, possibly with ferroelectric character, must accompany strain to make any cubic-to-tetragonal transition continuous. Experiments have indeed ruled out strain as the primary order parameter for Cd2Re2O7 (ref. 2), and both X-ray and neutron diffraction reveal broken inversion symmetry below Tc (refs 4–6). Theoretical analysis indicates that the true order parameter is a second-rank pseudotensor, corresponding to the Eu representation of the cubic point group1,2, shown in Fig. 1. The more familiar types of order all have lower rank: vectors for ferroelectricity, inversion-symmetric pseudovectors for ferromagnetism and second-rank tensors for ferroelasticity. Like the vector order of ferroelectricity, Eu tensor order in Cd2Re2O7 breaks inversion symmetry, but it is piezoelectric, not ferroelectric.

(Top centre) Cubic pyrochlore unit cell. The vertices of green tetrahedra indicate Re sites and red octahedra indicate O1 sites. Cd and O2 sublattices are not shown. (Top left and right) Distortions of neighbouring O1 octahedra associated with the two-fold degenerate Eu order parameter. Colour indicates oxygen displacement from the octahedron centre. Point group labels are shown together with the polynomial representation of a single octahedral distortion. Neighbouring octahedra have displacements with opposite sign, thus breaking inversion symmetry. (Bottom left and right) Pseudocubic unit cells of the distorted lattices, labelled by crystallographic group.

Our analysis of current experiments limits the possible low-temperature crystal structure to I4122 or  , but no further; details are provided in the Methods section. These two structures must be nearly degenerate to yield a Goldstone mode, but an infinitesimal anisotropy will introduce a small gap in the excitation spectrum and select a well-defined static structure12. At energies well above this gap, the dispersion relation of the Goldstone boson is expected to be linear3, like the spin-wave spectrum of an antiferromagnet. At temperatures above the anisotropy scale, thermal occupation of Goldstone bosons is expected to degrade the static order quadratically with temperature, just as spin waves degrade the sublattice magnetization of an antiferromagnet13.

, but no further; details are provided in the Methods section. These two structures must be nearly degenerate to yield a Goldstone mode, but an infinitesimal anisotropy will introduce a small gap in the excitation spectrum and select a well-defined static structure12. At energies well above this gap, the dispersion relation of the Goldstone boson is expected to be linear3, like the spin-wave spectrum of an antiferromagnet. At temperatures above the anisotropy scale, thermal occupation of Goldstone bosons is expected to degrade the static order quadratically with temperature, just as spin waves degrade the sublattice magnetization of an antiferromagnet13.

The tensor order of Cd2Re2O7 has been difficult to study experimentally because it is characterized by small atomic displacements, crystallographic twinning and high tensor rank. These challenges are well met by nonlinear optics. It is impossible to observe any d.c. piezoelectric effect in Cd2Re2O7 because it is a metal; nonetheless, the electronic transport properties are extremely sensitive to the structural transition, so we may expect similar sensitivity in states probed optically, where resonant enhancement from O→Re interband transitions are also expected to play a role14,15. Nonlinear optical susceptibilities are characterized by tensors of third or higher rank, so they can reveal symmetries that are hidden from other techniques. Second-harmonic generation (SHG) is commonly used to probe broken inversion symmetry, both at interfaces and in bulk materials16,17. More recently it has been used to characterize magnetic symmetries18,19. Furthermore, its high spatial resolution facilitates measurements in the presence of domain structure20.

In the electric dipole approximation, the nonlinear optical susceptibility for SHG is a third-rank tensor χj k l defined by

where ω is the incident optical frequency,  is the second-order nonlinear contribution to the polarization and E(ω) is the incident electric field amplitude. If equation (1) is to remain invariant under inversion, χj k l must be inversion-antisymmetric, reflecting broken inversion symmetry in the medium. In general χj k l has 27 complex independent elements, but experimental and crystal symmetries can reduce this number dramatically16. Application of the appropriate permutation and point group symmetry operations to equation (1) then gives χ123=χ132=−χ213=−χ231 as the only non-zero Cartesian tensor elements for I4122; similarly χ123=χ132=χ213=χ231, χ312=χ321 for

is the second-order nonlinear contribution to the polarization and E(ω) is the incident electric field amplitude. If equation (1) is to remain invariant under inversion, χj k l must be inversion-antisymmetric, reflecting broken inversion symmetry in the medium. In general χj k l has 27 complex independent elements, but experimental and crystal symmetries can reduce this number dramatically16. Application of the appropriate permutation and point group symmetry operations to equation (1) then gives χ123=χ132=−χ213=−χ231 as the only non-zero Cartesian tensor elements for I4122; similarly χ123=χ132=χ213=χ231, χ312=χ321 for  . Thus, a single complex number determines the nonlinear susceptibility of crystals with I4122 symmetry, and in general two complex numbers are required for

. Thus, a single complex number determines the nonlinear susceptibility of crystals with I4122 symmetry, and in general two complex numbers are required for  .

.

Figure 2 shows our experimental geometry. For concreteness we take the tetragonal c axis parallel to the cubic  axis, and define the polar axis associated with the angle α to be orthogonal to it. In practice, the c axis must be determined at low temperatures as described in the Methods section. In both crystallographic groups, the nonlinear polarization along one cubic direction is driven by the product of the electric fields along the other two. In the measurements discussed below, we find that when the SHG intensity is maximized, the input polarization αω and the output analyser angle α2ω are indeed perpendicular.

axis, and define the polar axis associated with the angle α to be orthogonal to it. In practice, the c axis must be determined at low temperatures as described in the Methods section. In both crystallographic groups, the nonlinear polarization along one cubic direction is driven by the product of the electric fields along the other two. In the measurements discussed below, we find that when the SHG intensity is maximized, the input polarization αω and the output analyser angle α2ω are indeed perpendicular.

(Left) Schematic diagram of the measurement system used for second-harmonic ellipsometry. Femtosecond laser pulses with  were focused through a dichroic beamsplitter (DBS) to a 100 μm-diameter spot on a cubic (111) surface of the sample (S); the reflected SHG is detected by a photomultiplier tube (PMT) after passing through an iris (φ). Input and output polarization states are specified with a half-wave plate (λ/2) and a crystal polarizer (P), respectively. (Right) Cubic crystallographic system

were focused through a dichroic beamsplitter (DBS) to a 100 μm-diameter spot on a cubic (111) surface of the sample (S); the reflected SHG is detected by a photomultiplier tube (PMT) after passing through an iris (φ). Input and output polarization states are specified with a half-wave plate (λ/2) and a crystal polarizer (P), respectively. (Right) Cubic crystallographic system  of the high-temperature phase and optical coordinate system

of the high-temperature phase and optical coordinate system  , viewed along the optical axis.

, viewed along the optical axis.

Figure 3 shows the temperature dependence of the normalized SHG amplitude,  , expected to be proportional to the order parameter amplitude. The clear onset below Tc directly implies that the order parameter breaks inversion symmetry. Polarization analysis indicates that the non-zero χ(2) above Tc results from the cubic sample surface and is unrelated to the Eu order at lower temperatures. At low temperatures, the ordered state degrades much more rapidly than mean-field theory would predict4, behaviour that we associate with the thermal occupation of Goldstone bosons.

, expected to be proportional to the order parameter amplitude. The clear onset below Tc directly implies that the order parameter breaks inversion symmetry. Polarization analysis indicates that the non-zero χ(2) above Tc results from the cubic sample surface and is unrelated to the Eu order at lower temperatures. At low temperatures, the ordered state degrades much more rapidly than mean-field theory would predict4, behaviour that we associate with the thermal occupation of Goldstone bosons.

The mean-field prediction is shown as a dotted line, and the solid line shows χ(2)(T)=1−(T/Tβ)2, expected from thermal occupation of the Goldstone mode. We obtain Tβ=230±9 K by carrying out least-squares fits over a range 5 K≤T≤Tmax, with Tmax varying from 25–150 K, then taking the mean and standard deviation of the parameter distribution. Repeated measurements at the same temperature indicate the statistical variation in the data. The inset shows the data and fit from the main panel, plotted as 1−χ(2) versus T 2.

A detailed theory for these novel lattice excitations does not yet exist. However, we can appeal to the analogy with antiferromagnetic spin waves to predict that at low temperatures χ(2)=1−(T/Tβ)2 with Tβ comparable to the theoretical mean-field Tc (ref. 13). Figure 3 shows that the agreement of this model with our data is superb. Our estimate of Tβ=230±9 K is somewhat above the actual Tc, as expected for the theoretical mean-field value. We expect this temperature dependence to only be valid at low temperatures, for which occupation densities are low and nonlinear mode coupling effects are minimized. That the data follow this temperature dependence up to nearly three-quarters of Tc indicates that the Goldstone bosons interact weakly, and that unlike spin waves these lattice modes may be treated quasiclassically.

The SHG polarization analysis shown in Fig. 4 now enables us to both assign the low-temperature crystallographic symmetry and associate it clearly with the Eu order parameter. As noted above, the nonlinear susceptibility is determined by one or two complex parameters, depending on the crystal symmetry. To measure these, a typical experimental approach is to construct a high-symmetry geometry that yields one or two real parameters from a fit to a one-dimensional (1D) data set such as the line cuts shown in Fig. 4. However, additional polarization effects can result from linear birefringence, crystal twinning and small experimental misalignments. These will all tend to corrupt an analysis that assumes a more constrained experimental geometry. Also, distinct physical symmetries often are not naturally expressed in the experimental coordinates, so multiple effects can contribute to the signal variation when a single experimental parameter changes. We have developed an approach that uses 2D data sets obtained by varying αω and α2ω, together with an analysis based on the irreducible group representations of the physical symmetries17,21.

a, Scaled SHG power P2ωsc(αω,α2ω) obtained at T=135 K (top) and at T=4 K (bottom). Also shown are data points and a model curve (η1=τ=0,Φ=1) along the line cut indicated in red, P2ωsc(αω=π,α2ω) at T=135 K. b, Model calculations (τ=0,Φ=1) for the two Eu basis states.c, Model calculations for the  point group with various values of τ and Φ. Top: Φ=1, τ/η2 varying over the complex plane, with τ/η2=0 indicated with a red square. Substituting τ/η2→(τ/η2)* yields identical results. Bottom: τ/η2=0, |Φ|=1 and arg(Φ)∈[0,π]. Variation with |Φ| is much weaker. d, Top: Best-fit model of the 2D data set from T=135 K, shown with experimental data and the model curve from a cut along the red line P2ωsc(αω=π/2,α2ω). Bottom: Polarized white light micrograph of the tetragonal domain structure at T=77 K. The scale bar represents 100 μm.

point group with various values of τ and Φ. Top: Φ=1, τ/η2 varying over the complex plane, with τ/η2=0 indicated with a red square. Substituting τ/η2→(τ/η2)* yields identical results. Bottom: τ/η2=0, |Φ|=1 and arg(Φ)∈[0,π]. Variation with |Φ| is much weaker. d, Top: Best-fit model of the 2D data set from T=135 K, shown with experimental data and the model curve from a cut along the red line P2ωsc(αω=π/2,α2ω). Bottom: Polarized white light micrograph of the tetragonal domain structure at T=77 K. The scale bar represents 100 μm.

In the usual notation for the representations of the cubic point group22, the susceptibility in the I4122 crystal structure transforms as Eu(1), whereas in  the susceptibility transforms as the direct sum

the susceptibility transforms as the direct sum  . We can express this decomposition in Cartesian form by associating the complex parameters η1,η2 and τ with Eu(1),Eu(2) and A2u respectively. In the experimental geometry of Fig. 2, this gives a nonlinear polarization

. We can express this decomposition in Cartesian form by associating the complex parameters η1,η2 and τ with Eu(1),Eu(2) and A2u respectively. In the experimental geometry of Fig. 2, this gives a nonlinear polarization

where  indicates that we have projected out the non-radiating component that lies along the optical axis. Neglecting optical anisotropy, the radiated SHG field will be proportional to

indicates that we have projected out the non-radiating component that lies along the optical axis. Neglecting optical anisotropy, the radiated SHG field will be proportional to  . For Eu order, linear birefringence is expected to appear as a secondary order parameter with Eg(2) symmetry, just as strain does. We model this birefringence by introducing a phenomenological complex parameter Φ, and letting the radiated SHG field be

. For Eu order, linear birefringence is expected to appear as a secondary order parameter with Eg(2) symmetry, just as strain does. We model this birefringence by introducing a phenomenological complex parameter Φ, and letting the radiated SHG field be  . We find similar freedom in Eω unnecessary.

. We find similar freedom in Eω unnecessary.

For αω={0,π}, the incident polarization is along  , so Ey=0 and we expect no SHG at all from the I4122 crystal structure, even in the presence of birefringence. Instead, we see a sinusoidal variation of the SHG power that has a maximum at α2ω=π/2, perpendicular to the incident polarization. We can conclude immediately from this observation that order parameter anisotropy favours the low-temperature crystallographic symmetry

, so Ey=0 and we expect no SHG at all from the I4122 crystal structure, even in the presence of birefringence. Instead, we see a sinusoidal variation of the SHG power that has a maximum at α2ω=π/2, perpendicular to the incident polarization. We can conclude immediately from this observation that order parameter anisotropy favours the low-temperature crystallographic symmetry  . However, theoretical plots with τ=0 and Φ=1, shown in Fig. 4b, reveal subtle differences from the data that a complete description must accommodate. Figure 4c shows that the model variation with τ and arg(Φ) is readily distinguished, and comparison with Fig. 4a shows that arg(Φ) is more significant for characterizing the experimental data.

. However, theoretical plots with τ=0 and Φ=1, shown in Fig. 4b, reveal subtle differences from the data that a complete description must accommodate. Figure 4c shows that the model variation with τ and arg(Φ) is readily distinguished, and comparison with Fig. 4a shows that arg(Φ) is more significant for characterizing the experimental data.

With the Eu order parameter we expect τ∝η23 to be small near Tc, even although it is allowed in the general  crystal symmetry1. This allows a further experimental test of the theory. We can associate τ/η2 directly with the SHG power variation over the line cut with Ex=0 in Fig. 4d. Consistent with Eu order, a nonlinear least-squares fit to the 2D data set at T=135 K yields best-fit parameters

crystal symmetry1. This allows a further experimental test of the theory. We can associate τ/η2 directly with the SHG power variation over the line cut with Ex=0 in Fig. 4d. Consistent with Eu order, a nonlinear least-squares fit to the 2D data set at T=135 K yields best-fit parameters  and

and  , together with a small constant offset

, together with a small constant offset  that we associate with surface SHG and instrumental background. The sensitivity to optical alignment creates systematic error that dominates statistical uncertainty, but contours of the χ2 surface are nearly circular in the complex τ/η2 plane and we can set a bound of 0.5 on |τ/η2| through visual inspection of model plots such as those in Fig. 4. The model results shown in Fig. 4d are in excellent agreement with experiment.

that we associate with surface SHG and instrumental background. The sensitivity to optical alignment creates systematic error that dominates statistical uncertainty, but contours of the χ2 surface are nearly circular in the complex τ/η2 plane and we can set a bound of 0.5 on |τ/η2| through visual inspection of model plots such as those in Fig. 4. The model results shown in Fig. 4d are in excellent agreement with experiment.

The properties of tensor order in Cd2Re2O7 exemplify the notion, pioneered by Landau and now firmly embedded in physics, that the low-energy properties of complex systems can be described with startling success by using just general symmetry principles and a few experimental inputs23. They may also serve as a foothold in reaching a better understanding of metals. One of the challenges for understanding how electrons travel in oxides is that the complexity of their interactions requires more sophisticated use of the standard principles of condensed-matter physics, and may even require the invention of new ones. With the structural aspects of the ordered state of Cd2Re2O7 now clearly identified and a guiding analogy with magnetism established, significant simplification has been achieved, and analysis of its intriguing electronic properties may proceed more effectively.

Methods

Analysis of current experiments

Below Tc=200 K Cd2Re2O7 loses three-fold rotation and inversion symmetries in a continuous ferrodistortive phase transition from an ideal pyrochlore structure, as discussed in ref. 2; the loss of inversion symmetry is further supported by the present work. Magnetic order on the rhenium sites is excluded by the absence of nuclear quadrupole resonance hyperfine splitting9. Sergienko and Curnoe1 used Landau theory to deduce that a continuous phase transition from  to a non-magnetic state without inversion symmetry can only yield 14 possible space groups (their Table II). Of these, only I4122 and

to a non-magnetic state without inversion symmetry can only yield 14 possible space groups (their Table II). Of these, only I4122 and  are consistent with the Raman observation of a Goldstone mode3, as they are the only basis vectors of a single O(n),n>1 order parameter that exhibits no fourth-order anisotropy in the Landau free energy1.

are consistent with the Raman observation of a Goldstone mode3, as they are the only basis vectors of a single O(n),n>1 order parameter that exhibits no fourth-order anisotropy in the Landau free energy1.

Assignment of the low-temperature crystal structure from diffraction studies is ambiguous, and limited by the unusually small lattice displacements in the ordered state4,5,6. In the low-temperature phase, new X-ray diffraction peaks appear at (0, 0, 10), (0, 6, 4) and at permutations of these cubic indices5. High-resolution X-ray measurements show further that the (0, 0, 12) peak, allowed in the ideal pyrochlore structure, exhibits a weak splitting, whereas no splitting is resolved for the (0, 0, 10) peak. In an untwinned crystal the (0, 0, 10) tetragonal reflection is allowed in  and forbidden in I4122; this seems to be the basis for the

and forbidden in I4122; this seems to be the basis for the  assignment in ref. 5. The crystal is clearly twinned in this study, however, and in this case all of the peaks observed in ref. 5 are consistent with both I4122 and

assignment in ref. 5. The crystal is clearly twinned in this study, however, and in this case all of the peaks observed in ref. 5 are consistent with both I4122 and  (ref. 24). Subsequent powder neutron diffraction measurements were shown to be more consistent with

(ref. 24). Subsequent powder neutron diffraction measurements were shown to be more consistent with  than with

than with  at low temperatures, but no comparison was made to I4122 (ref. 6). The role of twinning was recognized in ref. 4, and an assignment to I4122 or I41 was based on the recognition that the cubic (0, 0, 10) peak would not split for these structures because the (0, 0, 10) tetragonal reflection is forbidden. These measurements were resolution-limited, however, and there is nothing to prevent an approximate, non-space-group absence in the

at low temperatures, but no comparison was made to I4122 (ref. 6). The role of twinning was recognized in ref. 4, and an assignment to I4122 or I41 was based on the recognition that the cubic (0, 0, 10) peak would not split for these structures because the (0, 0, 10) tetragonal reflection is forbidden. These measurements were resolution-limited, however, and there is nothing to prevent an approximate, non-space-group absence in the  structure. Given the unambiguous evidence for an

structure. Given the unambiguous evidence for an  assignment provided here, it seems likely that this occurs.

assignment provided here, it seems likely that this occurs.

In some experiments, an additional first-order transition is observed near 120 K (refs 25–30). There is evidence that this transition is induced by sample disorder29, and it is not consistently observed in crystals grown at Oak Ridge. We see no evidence of this transition in our experiments, as can be seen by comparing measurements at T=5 K and T=135 K in Fig. 4a. Nevertheless, if we assume that this transition is intrinsic, our results clearly exclude the currently favoured I4122 space group, but could be consistent with an F222 space group if the transition is primarily associated with the cadmium sublattice30.

Optical second-harmonic generation

An optical second harmonic at 400 nm was detected with a blue-sensitive photomultiplier tube after passing the reflected light through dichroic filters. The properties of χj k l in Cd2Re2O7 dictate that we use a (111) cubic surface for study. At normal incidence to a cubic (100) surface, the nonlinear polarization would be along the optical axis and not radiate. We have verified that at the intensities used in this experiment, the SHG signal scales with the square of the incident power, as expected for a second-order optical nonlinearity. We have also confirmed with magnetic susceptibility measurements that Tc=200 K in this sample, about ten degrees above the apparent Tc in our measurements. This difference is independent of laser power, so it is not a simple heating effect, and the apparent Tc exhibits a hysteretic shift of about 5 K under temperature cycling that is not observed with other experimental probes. We tentatively attribute this behaviour to laser-induced domain formation.

Optical alignment

Optical alignment made use of the 2D data visualization shown in Fig. 4. By symmetry, the SHG power P2ω should satisfy P2ω(π−αω,π−α2ω)=P2ω(αω,α2ω). Deviations from this symmetry can be readily identified in the 2D data, indicating misalignment, and in practice this provides a stringent check that the angle of incidence is zero. We also identified the  axis with one of the three cubic axes by demanding that this symmetry be satisfied, after using X-rays to orient the Cd2Re2O7 crystal at room temperature. Finally, we have found that in highly twinned regions, diffracted SHG beams cause the structure of the 2D plot to change as a function of the detector iris diameter. This allowed us to confirm that we were observing a single tetragonal domain, after initial alignment based on correlating the laser spot position with polarized light microscopy images. This spot was located in a relatively large domain near the centre of the image shown in Fig. 4d when the results in Fig. 4a were obtained. Although the incident spot diameter was 100 μm, optical nonlinearity reduces the region probed by SHG to 50 μm.

axis with one of the three cubic axes by demanding that this symmetry be satisfied, after using X-rays to orient the Cd2Re2O7 crystal at room temperature. Finally, we have found that in highly twinned regions, diffracted SHG beams cause the structure of the 2D plot to change as a function of the detector iris diameter. This allowed us to confirm that we were observing a single tetragonal domain, after initial alignment based on correlating the laser spot position with polarized light microscopy images. This spot was located in a relatively large domain near the centre of the image shown in Fig. 4d when the results in Fig. 4a were obtained. Although the incident spot diameter was 100 μm, optical nonlinearity reduces the region probed by SHG to 50 μm.

References

Sergienko, I. A. & Curnoe, S. H. Structural order parameter in the pyrochlore superconductor Cd2Re2O7 . J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 72, 1607–1610 (2003).

Sergienko, I. A. et al. Metallic “ferroelectricity” in the pyrochlore Cd2Re2O7 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 065501 (2004).

Kendziora, C. A. et al. Goldstone-mode phonon dynamics in the pyrochlore Cd2Re2O7 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 125503 (2005).

Castellan, J. P. et al. Structural ordering and symmetry breaking in Cd2Re2O7 . Phys. Rev. B 66, 134528 (2002).

Yamaura, J. & Hiroi, Z. Low temperature symmetry of pyrochlore oxide Cd2Re2O7 . J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 71, 2598–2600 (2002).

Weller, M. T., Hughes, R. W., Rooke, J., Knee, C. S. & Reading, J. The pyrochlore family—a potential panacea for the frustrated perovskite chemist. Dalton Trans. 3032–3041 (2004).

Hanawa, M. et al. Superconductivity at 1 K in Cd2Re2O7 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 187001 (2001).

Jin, R. et al. Fluctuation effects on the physical properties of Cd2Re2O7 near 200 K. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14, L117–L123 (2002).

Vyaselev, O. et al. Superconductivity and magnetic fluctuations in Cd2Re2O7 via Cd nuclear magnetic resonance and Re nuclear quadrupole resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 017001 (2002).

Sakai, H. et al. Low-temperature structural change and magnetic anomaly in superconducting Cd2Re2O7 . Phys. Rev. B 66, 100509(R) (2002).

Anderson, P. W. & Blount, E. I. Symmetry considerations on martensitic transformations: “Ferroelectric” metals? Phys. Rev. Lett. 14, 217–219 (1965).

Anderson, P. W. An approximate quantum theory of the antiferromagnetic ground state. Phys. Rev. 86, 694–701 (1952).

Kubo, R. The spin-wave theory of antiferromagnetics. Phys. Rev. 87, 568–580 (1952).

Singh, D. J., Blaha, P., Schwarz, K. & Sofo, J. O. Electronic structure of the pyrochlore metals Cd2Os2O7 and Cd2Re2O7 . Phys. Rev. B 65, 155109 (2002).

Harima, H. Electronic bandstructures on 5d-transition metal pyrochlore: Cd2Re2O7 and Cd2Os2O7 . J. Phys. Chem. Solids 63, 1035–1038 (2002).

Boyd, R. W. Nonlinear Optics 2nd edn (Academic, San Diego, 2003).

Plocinik, R. M., Everly, R. M., Moad, A. J. & Simpson, G. J. Modular ellipsometric approach for mining structural information from nonlinear optical polarization analysis. Phys. Rev. B 72, 125409 (2005).

Hübner, W. H., Bennemann, K. H. & Böhmer, K. Theory for the nonlinear optical response of transition metals: Polarization dependence as a fingerprint of the electronic structure at surfaces and interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17597–17605 (1994).

Fiebig, M., Pavlov, V. V. & Pisarev, R. V. Second-harmonic generation as a tool for studying electronic and magnetic structures of crystals: Review. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 22, 96–118 (2005).

Fiebig, M., Lottermoser, T., Fröhlich, D., Goltsev, A. V. & Pisarev, R. V. Observation of coupled magnetic and electric domains. Nature 419, 818–820 (2002).

Jerphagnon, J., Chemla, D. & Bonneville, R. The description of physical properties of condensed matter using irreducible tensors. Adv. Phys. 27, 609–650 (1978).

Tinkham, M. Group Theory and Quantum Mechanics (International Series in Pure and Applied Physics, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1964).

Anderson, P. W. Basic Notions of Condensed Matter Physics (Benjamin-Cummings, Menlo Park, 1984).

Hahn, T. (ed.) International Tables for Crystallography 5th edn, Vol. A (Kluwer, Dordrecht, 2002).

Hiroi, Z., Yamaura, J., Muraoka, Y. & Hanawa, M. Second phase transition in pyrochlore oxide Cd2Re2O7 . J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 71, 1634–1636 (2002).

Hiroi, Z. & Hanawa, M. Superconducting properties of the pyrochlore oxide Cd2Re2O7 . J. Phys. Chem. Solids 63, 1021–1026 (2002).

Arai, K. et al. Structural transition in the pyrochlore superconductor Cd2Re2O7 observed by Re nuclear quadrupole resonance. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14, L461–L466 (2002).

Barišić, N. et al. Electrical properties of Cd2Re2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 67, 245112 (2003).

Lu, C. et al. Imperfection-driven phase transition at 120 K in Cd2Re2O7 . Phys. Rev. B 70, 092506 (2004).

Knee, C. S. et al. Order-disorder-order phase transitions in the pyrochlore superconductor Cd2Re2O7 . Phys. Rev. B 71, 214518 (2005).

Acknowledgements

Research at SFU was supported by the National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research Program in Quantum Materials, the Sloan Foundation and the Research Corporation. Research at Oak Ridge/UT is sponsored by the Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, US Department of Energy, under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725 with Oak Ridge National Laboratory, managed and operated by UT-Battelle, LLC. We thank Z.-G. Ye for use of his polarized light microscope; we also thank him, D. Broun, B. Gaulin, I. Herbut, C. Kendziora, G. Leach and D. Singh for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C.P. and J.S.D. conceived and designed the experiments; J.C.P. and M.D.C. carried them out, with crystals prepared and characterized by J.H., R.J. and D.M. J.C.P., M.D.C., J.S.D. and I.A.S. contributed to the measurement analysis. J.C.P. and J.S.D. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Petersen, J., Caswell, M., Dodge, J. et al. Nonlinear optical signatures of the tensor order in Cd2Re2O7 . Nature Phys 2, 605–608 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys392

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys392