Abstract

Radiation pressure is associated with the momentum of light1,2, and it plays a crucial role in a variety of physical systems3,4,5,6. It is usually assumed that both the optical momentum and the radiation-pressure force are naturally aligned with the propagation direction of light, given by its wavevector. Here we report the direct observation of an extraordinary optical momentum and force directed perpendicular to the wavevector, and proportional to the optical spin (degree of circular polarization). Such an optical force was recently predicted for evanescent waves7 and other structured fields8. It can be associated with the ’spin-momentum’ part of the Poynting vector, introduced by Belinfante in field theory 75 years ago9,10,11. We measure this unusual transverse momentum using a femtonewton-resolution nano-cantilever immersed in an evanescent optical field above the total internal reflecting glass surface. Furthermore, the measured transverse force exhibits another polarization-dependent contribution determined by the imaginary part of the complex Poynting vector. By revealing new types of optical forces in structured fields, our findings revisit fundamental momentum properties of light and enrich optomechanics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Since Euler’s studies of classical sound waves, the wave momentum has been naturally associated with the propagation direction of the wave, that is, the normal to wavefronts, or the wavevector. This idea was mathematically formulated by de Broglie for quantum matter waves: p = ℏ k, where p is the momentum, k is the wavevector and ℏ is the reduced Planck constant. In both classical and quantum cases, the wave momentum can be measured by means of the pressure force on an absorbing or scattering detector. In agreement with this, Maxwell claimed in his celebrated electromagnetic theory that ‘there is a pressure in the direction normal to the waves’1. However, pioneering works by Poynting introduced the electromagnetic momentum density as a cross product of the electric and magnetic field vectors2,12:  ∝ E × B. Unlike the straightforward de Broglie formula, the Poynting momentum is not obviously associated with the wavevector k. It is indeed aligned with the wavevector in the simplest case of a homogeneous plane electromagnetic wave. However, in more complicated yet typical cases of structured optical fields13,14 (for example, interference, optical vortices, or near fields) the direction of

∝ E × B. Unlike the straightforward de Broglie formula, the Poynting momentum is not obviously associated with the wavevector k. It is indeed aligned with the wavevector in the simplest case of a homogeneous plane electromagnetic wave. However, in more complicated yet typical cases of structured optical fields13,14 (for example, interference, optical vortices, or near fields) the direction of  can differ from the wavevector directions7,8.

can differ from the wavevector directions7,8.

Notably, the origin of this discrepancy between the Poynting momentum and wavevector lies within the framework of relativistic field theory (Supplementary Information). The conserved momentum of the electromagnetic field is associated with the translational symmetry of spacetime through Noether’s theorem10,15. Applied to the electromagnetic field Lagrangian, this theorem produces the so-called canonical momentum density Pcan. In the quantum-field framework, the canonical momentum generates spatial translations of the field, in the same way as the de Broglie formula is associated with the operator  generating translations of a quantum wavefunction. Therefore, the canonical momentum density of monochromatic optical fields is naturally associated with the local wavevector kloc of the wave electric field, which is determined by the phase gradient normal to the wavefront7,8,13,14,15.

generating translations of a quantum wavefunction. Therefore, the canonical momentum density of monochromatic optical fields is naturally associated with the local wavevector kloc of the wave electric field, which is determined by the phase gradient normal to the wavefront7,8,13,14,15.

However, resolving fundamental difficulties with the canonical stress-energy tensor (which is non-symmetric and gauge-dependent), in 1940 Belinfante added a ‘virtual’ contribution to get this to agree with the usual electromagnetic stress-energy tensor (symmetric and gauge-invariant)9,10,11,15. In monochromatic optical fields, assuming the Coulomb gauge, Belinfante’s addition to the electromagnetic momentum is a solenoidal edge current Pspin = (1/2)∇ × S produced by the spin angular momentum density S (that is, the oriented ellipticity of the local polarization) of the field. Owing to its solenoidal nature, this spin momentum does not transport energy, and is usually considered as unobservable per se. In contrast to Pcan, the Belinfante spin momentum Pspin is determined by the circular polarization and inhomogeneity of the field rather than by its wavevector7,8,9,10,11.

Thus, the well-known Poynting vector represents a sum of qualitatively different canonical and spin contributions: Pcan + Pspin =  . Moreover, it is the Belinfante spin momentum that is responsible for the difference between the local propagation and Poynting-vector directions in structured light.

. Moreover, it is the Belinfante spin momentum that is responsible for the difference between the local propagation and Poynting-vector directions in structured light.

The above structure of the electromagnetic momentum has traditionally been regarded as an abstract field-theory construction. However, recently some of us argued7 that one of the simplest inhomogeneous optical fields—a single evanescent wave—offers a unique opportunity to investigate, simultaneously and independently, the canonical and spin momenta of light in the laboratory environment (see Fig. 1). Considering the total internal reflection of a polarized plane wave at the glass–air interface, the canonical momentum density in the evanescent field in the air is proportional to its longitudinal wavevector:  . At the same time, the Poynting vector in an evanescent wave has an unusual transverse component, first noticed by Fedorov 60 years ago16. Remarkably, this component is proportional to the degree of circular polarization (helicity) σ and has a pure Belinfante spin origin:

. At the same time, the Poynting vector in an evanescent wave has an unusual transverse component, first noticed by Fedorov 60 years ago16. Remarkably, this component is proportional to the degree of circular polarization (helicity) σ and has a pure Belinfante spin origin:

. Here k is the vacuum wavenumber, kz > k, and

. Here k is the vacuum wavenumber, kz > k, and  is the parameter of the vertical exponential decay of the evanescent wave amplitude ∝ exp(−κx). Thus, if the spin momentum and Poynting vector are observable physical quantities, this should lead to an extraordinary helicity-dependent optical force, which is orthogonal to the propagation direction (wavevector) of the evanescent wave.

is the parameter of the vertical exponential decay of the evanescent wave amplitude ∝ exp(−κx). Thus, if the spin momentum and Poynting vector are observable physical quantities, this should lead to an extraordinary helicity-dependent optical force, which is orthogonal to the propagation direction (wavevector) of the evanescent wave.

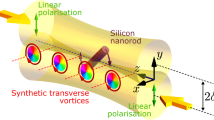

a, The evanescent wave is generated by the total internal reflection of a polarized plane wave at the glass–air interface. It carries longitudinal canonical momentum determined by its wavevector, and also exhibits transverse spin momentum, which is determined by the degree of circular polarization (helicity) of the field7. b, The longitudinal canonical momentum produces the well-known radiation pressure in light–matter interactions, whereas the transverse spin momentum exerts a weak helicity-dependent force orthogonal to the propagation direction of light.

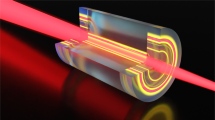

Here we present a direct measurement of the transverse helicity-dependent momentum and force in an evanescent wave, using a recently developed atomic force microscope: the lateral molecular force microscope (LMFM)17. Although conventional atomic force microscopes have the highest sensitivity to the vertical (that is, normal to the interface) force component, the LMFM geometry, using a cantilever orthogonal to the surface, is ideal to measure the optical momenta parallel to the glass–air interface (see Fig. 2a). Similar sensors, perpendicular to a substrate, recently showed an extreme force resolution in various systems17,18,19,20.

a, The LMFM set-up. The red laser 1 produces the evanescent field to be probed. Its intensity is modulated and the polarization is controlled by a rotating quarter waveplate (QWP). The green laser 2 images the position of the cantilever probing the evanescent field of laser 1. b, Atomic force microscope image of the free end of the cantilever. It has a complex shape with bevelled edges and surface inhomogeneities caused by the etching process. c, Variations of the polarization state of the incident laser-1 field, caused by rotations of the QWP in the range of angles −45° ≤ φ ≤ 45°, are represented by the black curve on the Poincaré sphere. The values φ = −45°, 0° and 45° correspond to the right-hand circular (R), horizontal linear (s) and left-hand circular (L) polarizations, respectively. d, Left: top view of the cantilever, whose shape has a y → −y asymmetry (see b). This produces a transverse radiation-pressure force from the longitudinal canonical momentum of the field, and mixes radiation-pressure and spin-momentum effects with a relative weight θ′ ≪ 1. Right: This mixing is modelled numerically using a symmetric cuboidal cantilever rotated by a small angle θ ≪ 1 about its vertical axis.

Importantly, the canonical and spin momenta of light manifest themselves very differently in light–matter interactions7,8 (see Fig. 1b). The usual radiation pressure is produced by the canonical momentum (even though it is often attributed to the Poynting vector), and the corresponding force (also called the ‘scattering force’) is always longitudinal—that is, aligned with the wave propagation7,8,14,21,22,23: F‖press ∝ Pcan. In turn, the transverse spin momentum, in agreement with its ‘virtual’ nature, can produce only a very weak force, vanishing in the dipole-interaction approximation7,8: F⊥spin ∝ P⊥spin, |Fspin| ≪ |Fpress|. In our experiment, we were able to significantly enhance the manifestation of the weak transverse force, as LMFM uses a strongly anisotropic probe, which is highly sensitive to the optical force along one axis (Fig. 2). Namely, we used a planar dielectric nano-cantilever, which represents an ideal sensor for the force component normal to its plane17,18,19,20. Recently, there have been significant breakthroughs in the manufacturing of such highly compliant cantilevers, which are now truly nano-scale devices with femtonewton sensitivity19,20. Mounting the cantilever in the (x, z) plane of the evanescent wave (Fig. 1), one can measure the transverse y-component of the optical force.

We emphasize that the force we measure is neither the z-directed radiation-pressure (scattering) force1,2,3,4,5,6,21,22,23, nor the x-directed gradient force used for optical trapping3,4,21, but a novel type of optical force orthogonal to both the propagation and inhomogeneity directions. In contrast to the electric-dipole scattering and gradient forces, this weak force originates from the dipole–dipole coupling between electric and magnetic dipoles induced in matter, and in the generic case it contains two contributions proportional to the real and imaginary parts of the complex Poynting vector7,8,24. It is convenient to discriminate different types of optical forces by means of their dependence on the field polarization. Using the normalized Stokes-vector parameters  , the radiation-pressure and gradient forces depend only on the first Stokes parameter τ, whereas the weak transverse force has both the σ-dependent (F⊥spin ∝ P⊥spin) and χ-dependent (F⊥Im, originating from the transverse ‘imaginary Poynting vector’) contributions (Supplementary Information). In our experiment we observe both of these contributions, in agreement with recent theoretical predictions7.

, the radiation-pressure and gradient forces depend only on the first Stokes parameter τ, whereas the weak transverse force has both the σ-dependent (F⊥spin ∝ P⊥spin) and χ-dependent (F⊥Im, originating from the transverse ‘imaginary Poynting vector’) contributions (Supplementary Information). In our experiment we observe both of these contributions, in agreement with recent theoretical predictions7.

The experimental set-up shown in Fig. 2a is based on the LMFM described in ref. 20. The red laser 1 (wavelength λ = 2πk−1 = 660 nm) generates a z-propagating and x-decaying evanescent field at the glass–air interface through an objective-based total internal reflection system. The polarization state of this field is controlled by a quarter waveplate (QWP) with varying orientation angle φ. Rotation of the QWP in the range of angles −45° ≤ φ ≤ 45° drives the polarization of the incident light between opposite spin states—that is, between right-handed (σ = 1) and left-handed (σ = −1) circular polarizations on a path with non-zero τ and χ on the Poincaré  -sphere, as is shown in Fig. 2c. (Note that the polarization parameters of the evanescent wave differ slightly from those of the incident light, see Supplementary Information.) The cantilever, with a spring constant γ ≃ 2.1 × 10−5 N m−1, is manufactured from ultralow-stress silicon nitride (refractive index n = 2.3); it has thickness d ≃ 100 nm, width w ≃ 1,000 nm, and length l ≃ 120 μm (Fig. 2b). It is vertically mounted in the evanescent field, with its tip being 30 nm above the glass coverslip. Deflections of the cantilever, Δ, caused by optical forces, are registered using a detection system based on a non-interferometric scattered evanescent wave (SEW) method20. The SEW system involves the green laser 2 (wavelength 561 nm), and it allows the measurement, with a resolution of 1 nm, of the cantilever deflections Δ as well as its vertical position. The intensity of the evanescent field produced by the red laser 1 is ‘on–off’ modulated in time (TTL-modulation) to generate an intermittent force field. This allows us to isolate optical forces produced by the laser 1 on the constant background of other forces (for example, from the imaging laser 2), see Fig. 3a.

-sphere, as is shown in Fig. 2c. (Note that the polarization parameters of the evanescent wave differ slightly from those of the incident light, see Supplementary Information.) The cantilever, with a spring constant γ ≃ 2.1 × 10−5 N m−1, is manufactured from ultralow-stress silicon nitride (refractive index n = 2.3); it has thickness d ≃ 100 nm, width w ≃ 1,000 nm, and length l ≃ 120 μm (Fig. 2b). It is vertically mounted in the evanescent field, with its tip being 30 nm above the glass coverslip. Deflections of the cantilever, Δ, caused by optical forces, are registered using a detection system based on a non-interferometric scattered evanescent wave (SEW) method20. The SEW system involves the green laser 2 (wavelength 561 nm), and it allows the measurement, with a resolution of 1 nm, of the cantilever deflections Δ as well as its vertical position. The intensity of the evanescent field produced by the red laser 1 is ‘on–off’ modulated in time (TTL-modulation) to generate an intermittent force field. This allows us to isolate optical forces produced by the laser 1 on the constant background of other forces (for example, from the imaging laser 2), see Fig. 3a.

a, Right: typical cantilever-position trace, recorded at φ = −45°, while the laser-1 intensity is TTL-modulated at 1 Hz. Left: the histogram of the position distribution shows two Gaussian-like distributions separated by a distance Δ(φ). This yields the optical force acting on the cantilever: Fmeasured(φ) = γΔ(φ). b, The total force acting on the cantilever, Fmeasured(φ), as a function of the QWP angle φ. c,d, The longitudinal radiation-pressure force, F‖press(φ) − F‖press(0), and the weak transverse force F⊥(φ), which are retrieved from the φ-even (c) and φ-odd (d) parts of the total force Fmeasured(φ). The transverse force includes the σ-dependent contribution F⊥spin ∝ Pyspin from the Belinfante spin momentum, and also the χ-dependent part F⊥Im from the transverse ‘imaginary Poynting momentum’. The experimental results are compared with the results of numerical simulations of the θ-rotated cantilever (Fig. 2d) and calculations based on a simplified Mie-particle model (Supplementary Information). In panels b–d, the errors correspond approximately to the size of the symbols.

An ideal cantilever with a symmetric cuboidal shape mounted in the (x, z)-plane would be insensitive to the longitudinal radiation pressure and would measure only the weak transverse force. However, the reactive-ion etching in the cantilever fabrication process results in an imperfect asymmetric shape with bevelled edges and varying surface roughnesses19 (Fig. 2b). In particular, because the real cantilever has no mirror symmetry y → −y, there is an asymmetric y-scattering of the z-incident light, producing a transverse scattering force which can be associated with the longitudinal canonical momentum of the field (Fig. 2d). Thus, the real cantilever measures the weak transverse force with an inevitable small admixture of the longitudinal radiation-pressure effect: Fmeasured = F⊥ + θ′F‖press, where θ′ ≪ 1 is an unknown parameter. However, these two contributions have different dependences on the wave polarization, which allows us to separate the different forces unambiguously. Indeed, the radiation-pressure (canonical momentum) force depends only on the first Stokes parameter τ, and therefore is an even function of the QWP angle φ. In turn, the weak transverse force has the σ-dependent (Belinfante spin momentum) and χ-dependent (‘imaginary Poynting vector’) contributions, which are both odd functions of φ (Supplementary Information). Thus, the even and odd parts of the measured force Fmeasured(φ) correspond to the longitudinal radiation-pressure effects and the transverse weak force, respectively.

The results of our measurements are presented in Fig. 3. Figure 3a shows an example of the cantilever-position signal (detected by means of SEW by laser 2) varying in time owing to the intermittent force produced by the laser-1 evanescent field. The distance Δ(φ) between the centroids of the two Gaussian-like distributions, corresponding to the ‘on’ and ‘off’ laser 1, is a measure of the optical force: Fmeasured(φ) = γΔ(φ). To improve the resolution and average out thermal fluctuations, we accumulated two distributions over 30 ‘on–off’ cycles. The measured force Fmeasured(φ) versus the QWP angle φ is depicted in Fig. 3b. We neglect the φ-independent contributions and plot the force with respect to its reference value at φ = 0. It has a clearly asymmetric φ → −φ shape and different magnitudes for the right-hand and left-hand circular polarizations, which signals the presence of the φ-odd spin-dependent transverse force. By retrieving the φ-even and φ-odd parts of Fmeasured(φ), we separate the radiation-pressure force (Fig. 3c) and the weak transverse force (Fig. 3d). The radiation-pressure force is proportional to the longitudinal canonical momentum dependent on the Stokes parameter τ(F‖press ∝ Pzcan). In turn, analysing the φ-dependence of the odd part, we find that it consists of both the σ-dependent transverse spin momentum (F⊥spin ∝ Pyspin) and χ-dependent transverse ‘imaginary Poynting’ (F⊥Im) contributions, as shown in Fig. 3d and predicted in theory7. These are the central results of this paper. They clearly show the presence of the transverse spin-dependent optical force, which is orthogonal to both the propagation and decay directions of the evanescent wave. This confirms the presence and observability of the enigmatic Belinfante spin momentum, which so far has been considered as ‘virtual’. Furthermore, the measurements in Fig. 3b–d show that the spin momentum is indeed almost ‘invisible’: the canonical-momentum contribution to the force is still five times stronger in our experiment despite its small weighting constant θ′ (for an isotropic spherical particle it would be much stronger). These results prove that the Poynting vector, which has been used in optics for a century, does not present a single meaningful momentum of light, but rather a sum of two independent contributions of different nature and properties7,8.

To verify our theoretical interpretation of the experimental measurements, we performed numerical simulations and analytical model calculations of optical forces on a matter probe in the evanescent field. Numerical simulations were performed using the coupled-dipole method, which models the cantilever as an assembly of interacting point particles (Supplementary Information). As it is not practical to model the exact shape and inhomogeneities of the real cantilever, we used a simplified model of a cuboidal cantilever with the refractive index n = 2.3 and two geometric fitting parameters: its thickness d, which controls the ratio of the σ- and χ-contributions to the transverse force, and a small orientation angle θ, which controls the y → −y asymmetry of the cantilever and a small admixture of the τ-dependent longitudinal radiation-pressure force (see Fig. 2d). The results of these simulations are shown as curves in Fig. 3b–d; they perfectly match the experimental data using only the common scaling factor and the fitting parameters values d ≃ 140 nm and θ ≃ 0.08 (that is, 4.7°). Moreover, the same τ-dependent variations of the longitudinal force, as well as σ- and χ-dependent transverse force, are obtained, using different scaling factors, within a greatly simplified model of a spherical Mie particle interacting with the field7 (Supplementary Information; Fig. 3c, d). The main fitting parameter here is the particle radius, which is r ≃ 139 nm in our case. Importantly, the particle model provides analytical expressions for the forces, which confirm their direct proportionality to the canonical and spin momentum densities in optical fields7,8: Fzpress ∝ Pzcan and Fyspin ∝ Pyspin (Supplementary Information).

The numerical simulations also enabled us to investigate dependences of the radiation-pressure and transverse forces on the shape of the cantilever (see Supplementary Fig. 5). In particular, varying the cantilever width w (that is, its area) we found that the longitudinal force F‖press grows near-linearly with w, which reflects its usual radiation-pressure nature related to the planar surface of the cantilever. In contrast to this, the transverse force F⊥ approximately saturates after w reaches a few wavelengths. This means that the weak spin-dependent force associated with the Belinfante spin momentum is not a pressure force, but rather an edge effect related to wave diffraction on the vertical edges of the cantilever. Indeed, one can show analytically that the transverse force vanishes for an infinite lamina without edges aligned with the (x, z)-plane: Fy = 0. This is in extreme contrast to the infinite radiation-pressure force for the same lamina in the (y, z)-plane: Fzpress = ∞. This proves that the spin momentum does not exert the usual radiation pressure on planar objects. Nonetheless, it can be detected (as we do in this work) owing to its weak interaction with the edges of finite-size probes.

To conclude, our results re-examine one of the most basic properties of light: optical momentum and its manifestations in light–matter interactions. In contrast to numerous previous studies, which involved radiation pressure forces in the direction of propagation of light or trapping forces along the intensity gradients, we have observed, orthogonal to both of these directions, the extraordinary optical momentum and force. Remarkably, the transverse Belinfante momentum and force are determined by the spin (circular polarization) of light rather than by its wavevector. Our results demonstrate that the canonical and spin momenta, forming the Poynting vector within field theory, manifest themselves very differently in interactions with matter. This offers a new paradigm for studies and applications involving optical momentum and its manifestations in light–matter interactions3,4,5,6.

Notably, the interplay between the canonical and Belinfante–Poynting momenta is closely related to fundamental quantum and field-theory problems, such as ‘quantum weak measurements of photon trajectories’14,25, ‘local superluminal propagation of light’14,22,23, and the ‘proton spin crisis’ in quantum chromodynamics26. Furthermore, recently, a reconstruction (but not direct measurement) of the longitudinal (σ-independent) Belinfante momentum was reported27, which is associated with non-zero transverse spin density in structured fields7,8. In addition, there has been a strong interest in transverse spin-dependent optical forces near surfaces28,29,30, which, however, originate from various particle–surface interactions rather than from pure field properties.

All these studies reveal intriguing connections between fundamental quantum-mechanical/field-theory problems involving optical momentum/spin, and local light–matter interaction experiments with structured light fields. In this context, the LMFM technique used in our experiment offers a new platform for precision direction-resolved measurements of optical momenta and forces in structured light fields at subwavelength scales.

References

Jones, R. V. Pressure of radiation. Nature 171, 1089–1093 (1953).

Loudon, R. & Baxter, C. Contribution of John Henry Poynting to the understanding of radiation pressure. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 468, 1825–1838 (2012).

Ashkin, A. History of optical trapping and manipulation of small-neutral particle, atoms, and molecules. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. Electron. 6, 841–856 (2000).

Grier, D. G. A revolution in optical manipulation. Nature 424, 810–816 (2003).

Aspelmeyer, M., Kippenberg, T. J. & Marquardt, F. Cavity optomechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 1391–1452 (2014).

Kippenhahn, R., Weigert, A. & Weiss, A. Stellar Structure and Evolution (Springer, 1990).

Bliokh, K. Y., Bekshaev, A. Y. & Nori, F. Extraordinary momentum and spin in evanescent waves. Nature Commun. 5, 3300 (2014).

Bekshaev, A. Y., Bliokh, K. Y. & Nori, F. Transverse spin and momentum in two-wave interference. Phys. Rev. X 5, 011039 (2015).

Belinfante, F. J. On the current and the density of the electric charge, the energy, the linear momentum and the angular momentum of arbitrary fields. Physica 7, 449–474 (1940).

Soper, D. E. Classical Field Theory (Wiley, 1976).

Ohanian, H. C. What is spin? Am. J. Phys. 54, 500–505 (1986).

Jackson, J. D. Classical Electrodynamics 3rd edn (Wiley, 1999).

Berry, M. V. Optical currents. J. Opt. A 11, 094001 (2009).

Bliokh, K. Y., Bekshaev, A. Y., Kofman, A. G. & Nori, F. Photon trajectories, anomalous velocities, and weak measurements: a classical interpretation. New J. Phys. 15, 073022 (2013).

Bliokh, K. Y., Bekshaev, A. Y. & Nori, F. Dual electromagnetism: helicity, spin, momentum, and angular momentum. New J. Phys. 15, 033026 (2013).

Fedorov, F. I. To the theory of total reflection. Dokl. Akad. Nauk 105, 465–468 (1955); [translated and reprinted in J. Opt. 15, 014002 (2013)].

Scholz, T. et al. Processive behaviour of kinesin observed using micro-fabricated cantilevers. Nanotechnology 22, 095707 (2011).

Rugar, D., Budakian, R., Mamin, H. J. & Chui, B. W. Single spin detection by magnetic resonance force microscopy. Nature 430, 329–332 (2004).

Lee, D.-W. et al. Fabrication and evaluation of single-crystal silicon cantilevers with ultra-low spring constants. J. Micromech. Microeng. 15, 2179–2183 (2005).

Vicary, J. A., Ulcinas, A., Hörber, J. K. H. & Antognozzi, M. Micro-fabricated mechanical sensors for lateral molecular-force microscopy. Ultramicroscopy 111, 1547–1552 (2011).

Ashkin, A. & Gordon, J. P. Stability of radiation-pressure particle traps: an optical Earnshaw theorem. Opt. Lett. 8, 511–513 (1983).

Huard, S. & Imbert, C. Measurement of exchanged momentum during interaction between surface-wave and moving atom. Opt. Commun. 24, 185–189 (1978).

Barnett, S. M. & Berry, M. V. Superweak momentum transfer near optical vortices. J. Opt. 15, 125701 (2013).

Nieto-Vesperinas, M., Saenz, J. J., Gomez-Medina, R. & Chantada, L. Optical forces on small magnetodielectric particles. Opt. Express 18, 11428–11443 (2010).

Kocsis, S. et al. Observing the average trajectories of single photons in a two-slit interferometer. Science 332, 1170–1173 (2011).

Leader, E. & Lorce, C. The angular momentum controversy: What’s it all about and does it matter? Phys. Rep. 541, 163–248 (2014).

Neugebauer, M., Bauer, T., Aiello, A. & Banzer, P. Measuring the transverse spin density of light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 063901 (2015).

Scheel, S., Buhmann, S. Y., Clausen, C. & Schneeweiss, P. Directional spontaneous emission and lateral Casimir–Polder force on an atom close to a nanofiber. Phys. Rev. A 92, 043819 (2015).

Rodríguez-Fortuño, F. J., Engheta, N., Martínez, A. & Zayats, A. V. Lateral forces on nanoparticles near a surface under circularly-polarized plane-wave illumination. Nature Commun. 6, 8799 (2015).

Sukhov, S., Kajorndejnukul, V., Naraghi, R. R. & Dogariu, A. Dynamic consequences of optical spin–orbit interaction. Nature Photon. 9, 809–812 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (project LO1212), RIKEN iTHES Project, MURI Center for Dynamic Magneto-Optics via the AFOSR (grant number FA9550-14-1-0040), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A), and the Australian Research Council. M.A. and R.L.H. would like to thank Nick and Susan Woollacott who kindly funded the equipment used in this research, as well as A. Crimp, D. Engledew, J. Hugo and P. Dunton for their essential technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.R.B., R.L.H. and S.S. contributed equally to this work. K.Y.B., M.R.D. and M.A. conceived the idea of this research. M.A. and R.L.H. designed the experiment. C.R.B. performed the measurements. S.S. performed numerical simulations. R.L.H. and C.R.B. contributed to the cantilever characterization. C.R.B., J.S. and R.H. collected and analysed data. H.H. contributed to the experimental protocol and methods for data analysis. A.Y.B. provided analytical and semi-analytical calculations of optical forces. K.Y.B. performed theoretical analysis and wrote the paper with input from M.A., S.S., M.R.D., R.L.H., A.Y.B. and F.N.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary information (PDF 5839 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Antognozzi, M., Bermingham, C., Harniman, R. et al. Direct measurements of the extraordinary optical momentum and transverse spin-dependent force using a nano-cantilever. Nature Phys 12, 731–735 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3732

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3732

This article is cited by

-

Cooling the optical-spin driven limit cycle oscillations of a levitated gyroscope

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Robot-aided fN∙m torque sensing within an ultrawide dynamic range

Microsystems & Nanoengineering (2021)

-

Sensitive vectorial optomechanical footprint of light in soft condensed matter

Nature Photonics (2021)

-

Microwave photonic circulator based on optomechanical-like interactions

Quantum Information Processing (2021)

-

Chirality-assisted lateral momentum transfer for bidirectional enantioselective separation

Light: Science & Applications (2020)