Abstract

In quantum-enhanced sensing, non-classical states are used to improve the sensitivity of a measurement1. Squeezed light, in particular, has proved a useful resource in enhanced mechanical displacement sensing2,3,4,5,6,7,8, although the fundamental limit to this enhancement due to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle9,10,11 has not been encountered experimentally. Here we use a microwave cavity optomechanical system to observe the squeezing-dependent radiation pressure noise that necessarily accompanies any quantum enhancement of the measurement precision and ultimately limits the measurement noise performance. By increasing the measurement strength so that radiation pressure forces dominate the thermal motion of the mechanical oscillator, we exploit the optomechanical interaction to implement an efficient quantum nondemolition measurement of the squeezed light12. Thus, our results show how the mechanical oscillator improves the measurement of non-classical light, just as non-classical light enhances the measurement of the motion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In recent years, precision measurements of mechanical motion have become increasingly limited by quantum effects. Some prime laboratory examples have come from cavity optomechanical systems wherein the motion of a mechanical oscillator couples to a mode of an electromagnetic cavity resonator13. When the cavity is probed at its resonance frequency with a coherent state, any mechanical motion is transduced to a phase modulation of the returned probe. The probe’s phase noise therefore establishes the detection’s noise floor and ultimately limits the measurement’s signal-to-noise ratio. Typically, this noise floor is reduced by simply increasing the drive power, which decreases the phase imprecision of the interrogating field. In some cases, however, limited power availability or low material damage thresholds may occasionally call for the use of squeezed states to push the drive’s phase fluctuations below the shot noise limit (SNL), further suppressing the phase noise.

Improving the detector’s noise performance using phase-squeezed light does not come without its costs. Owing to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, suppressing the fluctuations of the phase quadrature leads to a commensurate increase in the drive’s amplitude fluctuations. These stronger fluctuations in turn generate an increased level of radiation pressure noise, which drives the motion of the mechanical oscillator. Until recently14,15,16, the influence of radiation pressure forces has largely been hidden by mechanical thermal noise, obscuring the full impact of the squeezing. As the ultimate measurement sensitivity relies on the delicate balance between these two noise sources, the limits of the quantum enhancement have not yet been encountered. Here we investigate these limits by interrogating a cavity optomechanical system using squeezed microwave radiation across regimes of weak and strong radiation pressure forces, characterizing the total measurement noise performance throughout.

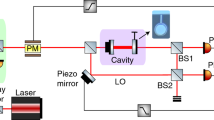

In our experiments (Fig. 1), the microwave ‘cavity’ consists of an aluminium 15 nH spiral inductor shunted by a mechanically compliant vacuum-gap capacitor17,18. We engineer the total cavity linewidth (κ/2π = 22.2 MHz) to be of the order of the mechanical resonance frequency of the capacitor’s primary flexural mode (Ωm/2π = 8.68 MHz) to maximize the measurement strength per cavity photon. The effects due to cavity loss are negligible as the cavity is highly overcoupled with an internal loss rate κ0 < 2π × 100 kHz (ref. 16). The circuit is cooled in a dilution refrigerator and held at a temperature of T = 40 mK, corresponding to an equilibrium phonon occupancy of approximately 95 quanta. We further reduce this phonon occupancy by sideband cooling the mechanical oscillator to an occupancy of nth = 10 and a mechanical linewidth of Γ/2π = 200 Hz throughout all of our experiments (see Supplementary Information). A state of microwave squeezed vacuum is prepared19 using a Josephson parametric amplifier (JPA) and combined with a strong microwave drive that is tuned to the cavity’s resonance frequency (ωc/2π = 6.89 GHz). The field emitted by the JPA is sufficiently broadband compared to the mechanical linewidth that the level of squeezing can be treated as constant near the mechanical resonance frequency (see Supplementary Information). By manipulating the phase of the squeezing, θ, relative to the phase of the drive, φ, we are able to prepare a variety of displaced squeezed states that we use to interrogate the optomechanical cavity by means of a reflection measurement. The reflected field is then amplified using a cryogenic high-electron-mobility transistor amplifier before being demodulated using a homodyne receiver.

a, Optical representation of the experiment. A displaced squeezed state is prepared by combining a strong coherent state with a state of squeezed vacuum using a 99:1 beamsplitter. The drive field then interrogates the motion of the mechanical oscillator, inducing phase modulation sidebands in the returned drive’s power spectral density (PSD) above and below the reflected drive’s carrier frequency. b, Equivalent microwave circuit. Squeezed vacuum is prepared by parametrically pumping a Josephson parametric amplifier (JPA) at twice the resonance frequency of the optomechanical cavity (2ωc). The squeezed state is then combined with the coherent drive through the coupled port of a 20 dB directional coupler. The optomechanical circuit (OM) is interrogated by means of a reflection measurement, and the reflected field is then amplified using a phase-insensitive high-electron-mobility transistor (HEMT) amplifier. c, False-colour image of the aluminium drum deposited on a sapphire substrate (blue) taken with a scanning electron microscope.

Figure 2 shows the power spectral density of the demodulated mechanical sidebands in the regime where the mechanical motion is dominated by radiation pressure effects. In this regime, the effects of the squeezing appear in two distinct ways in the spectra. The peak height of the Lorentzian lineshape at the mechanical resonance frequency, Ωm, is largely determined by the magnitude of the amplitude fluctuations of the drive field, which is responsible for the backaction. In contrast, the measurement noise floor is set by the fluctuations of the phase quadrature of the drive. At intermediate phases between amplitude and phase squeezing, the correlations of the drive field lead to constructive and destructive interference in the wings of the mechanical line (see Fig. 2d, e), yielding a Fano-like lineshape. It is precisely these correlations that advanced gravitational wave observatories will exploit to enhance the broadband strain sensitivities of their detectors away from the mechanical resonance frequency once radiation pressure forces become important20,21,22.

All plotted spectra are normalized to amplified shot noise. a, Broadband mechanical noise spectra in the presence of an unsqueezed drive as well as amplitude and phase squeezing. For this data, C = 70 and r = 0.9. b, Close-up of the Lorentzian mechanical sideband in the presence of various squeezed states. The area of each is proportional to the equilibrium mechanical mode temperature. Phase squeezing increases the measurement backaction compared with the unsqueezed case, and amplitude squeezing reduces the backaction. c, Zoomed-in depiction of the baseband noise away from the mechanical Lorentzian. The data have been smoothed using a moving average with a bin width of 30 points. The phase-squeezed drive lowers the noise floor whereas amplitude squeezing raises it. d,e, Asymmetric shape of the mechanical resonance at intermediate squeezing phases (C = 220). The plotted theory assumes no free parameters.

The full role of the squeezing can be rigorously understood by considering the interaction Hamiltonian that couples a cavity resonator mode  to a mechanical oscillator mode

to a mechanical oscillator mode  :

:

where g0 denotes the vacuum optomechanical coupling rate. In a linearized regime, a large coherent build-up of the cavity photons  achieves a parametric enhancement of the coupling rate g = g0α, which allows the interaction strength between the light field and the mechanical oscillator to be tuned by changing the drive power. We will parameterize the enhanced coupling rate in terms of the optomechanical cooperativity C ≡ 4g2/κΓ, where Γ and κ are the mechanical and cavity linewidths, respectively13. It is the cooperativity that weights how the fluctuations of the amplitude

achieves a parametric enhancement of the coupling rate g = g0α, which allows the interaction strength between the light field and the mechanical oscillator to be tuned by changing the drive power. We will parameterize the enhanced coupling rate in terms of the optomechanical cooperativity C ≡ 4g2/κΓ, where Γ and κ are the mechanical and cavity linewidths, respectively13. It is the cooperativity that weights how the fluctuations of the amplitude  and phase

and phase  quadratures of the drive field contribute to the detection’s total added noise.

quadratures of the drive field contribute to the detection’s total added noise.

To characterize the measurement’s noise performance, it will be useful to quantify the imprecision noise floor in units of equivalent thermal phonons

where we have assumed a homodyne detection of quantum efficiency ηdet (ref. 23) and introduced the weighted cooperativity  . As equation (2) confirms, nimp can be suppressed by squeezing the fluctuations of the drive’s phase quadrature or by increasing the cooperativity. The contribution to the thermal phonon occupancy due to measurement backaction, nba, is proportional to the variance of the light field’s amplitude quadrature according to

. As equation (2) confirms, nimp can be suppressed by squeezing the fluctuations of the drive’s phase quadrature or by increasing the cooperativity. The contribution to the thermal phonon occupancy due to measurement backaction, nba, is proportional to the variance of the light field’s amplitude quadrature according to

Thus, nimp and nba are related to one another by the light field’s Heisenberg uncertainty principle  . When interrogating the cavity with a coherent state, the variance of the drive’s amplitude and phase quadratures both obey

. When interrogating the cavity with a coherent state, the variance of the drive’s amplitude and phase quadratures both obey  , which determines the SNL of the light. In this case, the noise added by the detection (nadd = nimp + nba) is governed solely by the choice of measurement cooperativity, and the minimum value of added measurement noise (nadd > 1/2) directly follows from the Heisenberg uncertainty principle10,11,13,24. The introduction of squeezed light provides an additional parameter through which to reach the ultimate limit25,26 where nadd = 1/2. As is customary, we will parameterize the squeezing by associating the variance of the drive’s squeezed quadrature,

, which determines the SNL of the light. In this case, the noise added by the detection (nadd = nimp + nba) is governed solely by the choice of measurement cooperativity, and the minimum value of added measurement noise (nadd > 1/2) directly follows from the Heisenberg uncertainty principle10,11,13,24. The introduction of squeezed light provides an additional parameter through which to reach the ultimate limit25,26 where nadd = 1/2. As is customary, we will parameterize the squeezing by associating the variance of the drive’s squeezed quadrature,  , with the squeezing parameter r such that

, with the squeezing parameter r such that  . As equations (2) and (3) illustrate, the imprecision–backaction inequality nimp × nba ≥ 1/16 is maintained in the presence of the squeezing.

. As equations (2) and (3) illustrate, the imprecision–backaction inequality nimp × nba ≥ 1/16 is maintained in the presence of the squeezing.

By knowing the vacuum coupling rate (g0/2π = 170 Hz) and the full quantum state of the cavity field, it is straightforward to report the measurement’s total noise in phonon units (nimp + nba + nth + 1/2), which is portrayed in Fig. 3. In particular, we must consider the effects of a limited microwave transmittance between the JPA and the optomechanical circuit (ηin = 47 ± 2%) and a constant thermal occupancy of the cavity field (nc = 0.17), which act to limit the purity of the squeezing (see Supplementary Methods). The data show full quantitative agreement with the expected noise performance in all measurement regimes, including those where either nimp or nba dominates the detection’s total noise. Notably, we observe a nearly 3 dB reduction of the total measurement noise by using amplitude squeezing in the backaction limit (C ≫ nth). The minimum in the total measurement noise, however, is achieved at a much lower cooperativity where nimp = nba. Here, amplitude-squeezed light can in principle mitigate the effects of a finite detection efficiency26 and allow the measurement to more closely approach the ultimate quantum limit where nadd = 1/2. In Fig. 3a, we observe a minimum measurement noise of 13.4 phonons when interrogating the mechanical oscillator with an unsqueezed field. When amplitude-squeezed light is introduced, we find a noise reduction of 0.5 phonons relative to the unsqueezed case. It is important to emphasize, however, that this enhancement strongly depends on the purity of the squeezing and not just its magnitude. Here, a pure amplitude-squeezed state would have reduced the noise by nearly 2 phonons.

The uncertainties are estimated using 68% confidence intervals for the Lorentzian fit parameters. a, Total detected noise, expressed in units of phonons, versus cooperativity, C. In the presence of amplitude squeezing (blue squares), we observe more added noise in the imprecision limit and less added noise in the backaction limit compared with an unsqueezed drive (green circles). These behaviours are reversed in the presence of a phase-squeezed drive (red triangles). The ideal imprecision noise limits that would be obtained with perfect detection efficiency are portrayed in the lower left-hand corner. b, Contribution of imprecision noise to the total added noise. As the imprecision noise should scale inversely with C, we plot the product nimp × C, which should be constant. c, Measured equilibrium phonon occupancy in the presence of the various drive states.

Just as the squeezing can be used to enhance the detection of the mechanical oscillator, the mechanical oscillator can be used to enhance the detection of the squeezing. In either case, the characteristics of the measurement are embodied by the interaction Hamiltonian (equation (1)). Here, the coupled mechanical observable  fails to commute with its bare Hamiltonian

fails to commute with its bare Hamiltonian  , causing any measurement disturbance to feed back into

, causing any measurement disturbance to feed back into  during the course of the system’s evolution. This should be contrasted with the coupled cavity field observable

during the course of the system’s evolution. This should be contrasted with the coupled cavity field observable  , which suggests that the mechanical oscillator performs a quantum nondemolition (QND) measurement27 of the cavity photon number. In the linearized regime, we take

, which suggests that the mechanical oscillator performs a quantum nondemolition (QND) measurement27 of the cavity photon number. In the linearized regime, we take  , which transforms the QND observable to the fluctuations of the amplitude quadrature,

, which transforms the QND observable to the fluctuations of the amplitude quadrature,  , because

, because  . It is in this sense that the phonon field state performs a nondestructive detection of the light’s amplitude quadrature12.

. It is in this sense that the phonon field state performs a nondestructive detection of the light’s amplitude quadrature12.

Typically, a light field’s quantum state is tomographically reconstructed by detecting an ensemble of identically prepared states with a homodyne receiver. By rotating the phase of the receiver’s local oscillator, various quadratures of the light field can be selected over the course of many experiments, and the quantum state of the field can be reconstructed from the statistics. Here, as the mechanical mode is sensitive only to the drive’s amplitude fluctuations, we rotate the phase of the squeezing, θ, relative to the phase of the coherent drive, φ, to achieve the same goal. The equilibrium mechanical occupancy is sensitive to both the magnitude and phase of the squeezing, so each mechanical sideband contains information about both r and θ. Thus, we are able to completely characterize the squeezed state over a bandwidth comparable to the mechanical linewidth using a heterodyne measurement of the returned drive’s upper mechanical sideband. Unlike conventional homodyne detection, however, the QND measurement pursued here does not destroy the light field on its detection and ideally leaves the amplitude quadrature unperturbed by any measurement backaction (see Supplementary Information).

For the mechanical mode to facilitate an efficient detection of the squeezing, it is critical that the rate at which pump photons are scattered into the mechanical sidebands, Γscatter = 4g2κ/(κ2 + 4Ωm2), greatly exceed the rate of mechanical decoherence, nthΓ. In this limit, the state of the mechanical oscillator couples more strongly to the quantum correlations of the microwave field than to the mechanical thermal environment. Thus, even when being driven by amplitude-squeezed light, radiation pressure noise continues to strongly influence the equilibrium phonon occupancy. To demonstrate this idea, we measure the total noise power of the upper mechanical sideband at various measurement cooperativities as the squeezing phase, θ, is rotated. By normalizing the phase-dependent mechanical noise power to the detected level of mechanical noise in the presence of a coherent state drive, we reconstruct the squeezed state’s quadrature noise power in Fig. 4a. Just as with conventional homodyne detection, the measured level of squeezing can be quantified by an effective detection efficiency, ηdetOM, according to

At high drive strengths where nth ≫ nimp, ηeffOM scales with cooperativity according to ηdetOM = (1 + nthΓ/Γscatter)−1. At the highest measurement cooperativities accessible in our experiments, we expect ηdetOM ≍ 94%, which is confirmed in Fig. 4b. It should be emphasized that this inferred detection efficiency does not include the effects of microwave loss suffered by the squeezed state on its way to the detector. Our results are comparable to state-of-the-art microwave detection efficiencies achieved using JPAs28, and amount to a 30-fold improvement over the homodyne efficiency of the conventional detection chain used in these experiments (ηdet = 3%).

a, Average integrated noise power of the upper mechanical sideband (measured using a heterodyne receiver) as the squeezing phase θ is swept (the coherent phase φ is held constant). The colours denote different JPA drive powers and, correspondingly, different values of the squeezing parameter, r. The fits assume a squeezed thermal state subject to loss (see Supplementary Information). The squeezing shown in the inset is comparable to that used to obtain the data in Fig. 3. b, Squeezing parameter, r, measured using the optomechanical cavity versus similar results obtained using conventional homodyne detection performed with a large integration bandwidth (1,000 × Γ). The blue line depicts a slope of unity. c, Effective mechanical detection efficiency of the squeezing, ηdetOM, as a function of drive cooperativity, C (see equation (4)). The expected range of ηdetOM values (shaded blue) accounts for the uncertainty in the microwave transmittance (ηin = 47 ± 2%) between the JPA and the optomechanical cavity. The uncertainties in b and c correspond to the standard deviation of the mean over 20 experiments.

These measurements demonstrate both how quantum states of the light field can improve mechanical measurements and how mechanical systems can make improved measurements of the light. Looking forward, radiation pressure forces from squeezed light are expected to play an important role in determining the ultimate precision of future gravitational wave observatories21. Squeezed light could also prove to be a valuable resource for the preparation of squeezed states of mechanical motion29. Furthermore, cavity optomechanical systems in the backaction-dominated regime offer an ideal testbed for quantum-enhanced displacement sensing with other non-classical states of light1,22. Last, the QND nature of the measurement of the light field also opens the door for new types of mechanically mediated deterministic noiseless amplification30.

References

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Quantum-enhanced measurements beating the standard quantum limit. Science 306, 1330–1336 (2004).

McKenzie, K., Shaddock, D. A., McClelland, D. E., Buchler, B. C. & Lam, P. K. Experimental demonstration of a squeezing-enhanced power-recycled Michelson interferometer for gravitational wave detection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 231102 (2002).

Vahlbruch, H. et al. Demonstration of a squeezed-light-enhanced power- and signal-recycled Michelson interferometer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 211102 (2005).

Goda, K. et al. A quantum-enhanced prototype gravitational-wave detector. Nature Phys. 4, 472–476 (2008).

The LIGO Scientific Collaboration Enhanced sensitivity of the LIGO gravitational wave detector by using squeezed states of light. Nature Photon. 7, 613–619 (2013).

Taylor, M. A. et al. Biological measurement beyond the quantum limit. Nature Photon. 7, 229–233 (2013).

Hoff, U. B. et al. Quantum-enhanced micromechanical displacement sensitivity. Opt. Lett. 38, 1413–1415 (2013).

Pooser, R. C. & Lawrie, B. Ultrasensitive measurement of microcantilever displacement below the shot-noise limit. Optica 2, 393–399 (2015).

Caves, C. M. Quantum-mechanical noise in an interferometer. Phys. Rev. D 23, 1693–1708 (1981).

Braginsky, V. B., Khalili, F. Y. & Thorne, K. S. Quantum Measurement 1st edn (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1995).

Clerk, A. A., Devoret, M. H., Girvin, S. M., Marquardt, F. & Schoelkopf, R. J. Introduction to quantum noise, measurement, and amplification. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1155–1208 (2010).

Jacobs, K., Tombesi, P., Collett, M. J & Walls, D. F. Quantum-nondemolition measurement of photon number using radiation pressure. Phys. Rev. A 49, 1961–1966 (1994).

Aspelmeyer, M., Kippenberg, T. J. & Marquardt, F. Cavity optomechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 1391–1452 (2014).

Purdy, T. P., Peterson, R. W. & Regal, C. A. Observation of radiation pressure shot noise on a macroscopic object. Science 339, 801–804 (2013).

Schreppler, S. et al. Optically measuring force near the standard quantum limit. Science 344, 1486–1489 (2014).

Teufel, J. D., Lecocq, F. & Simmonds, R. W. Overwhelming thermomechanical motion with microwave radiation pressure shot noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 013602 (2016).

Cicak, K. et al. Low-loss superconducting resonant circuits using vacuum-gap-based microwave components. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 093502 (2010).

Teufel, J. D. et al. Circuit cavity electromechanics in the strong-coupling regime. Nature 471, 204–208 (2011).

Castellanos-Beltran, M. A., Irwin, K. D., Hilton, G. C., Vale, L. R. & Lehnert, K. W. Amplification and squeezing of quantum noise with a tunable Josephson metamaterial. Nature Phys. 4, 929–931 (2008).

Kimble, H. J., Levin, Y., Matsko, A. B., Thorne, K. S. & Vyatchanin, S. P. Conversion of conventional gravitational-wave interferometers into quantum nondemolition interferometers by modifying their input and/or output optics. Phys. Rev. D 65, 022002 (2001).

Schnabel, R., Mavalvala, N., McClelland, D. E. & Lam, P. K. Quantum metrology for gravitational wave astronomy. Nature Commun. 1, 121 (2010).

Demkowicz-Dobrzaski, R., Banaszek, K. & Schnabel, R. Fundamental quantum interferometry bound for the squeezed-light-enhanced gravitational wave detector GEO 600. Phys. Rev. A 88, 041802 (2013).

Leonhardt, U. Measuring the Quantum State of Light (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005).

Caves, C. M., Thorne, K. S., Drever, R. W. P., Sandberg, V. D. & Zimmermann, M. On the measurement of a weak classical force coupled to a quantum-mechanical oscillator. I. Issues of principle. Rev. Mod. Phys. 52, 341–392 (1980).

Arcizet, O., Briant, T., Heidmann, A. & Pinard, M. Beating quantum limits in an optomechanical sensor by cavity detuning. Phys. Rev. A 73, 033819 (2006).

Kerdoncuff, H., Hoff, U. B., Harris, G. I., Bowen, W. P. & Andersen, U. L. Squeezing-enhanced measurement sensitivity in a cavity optomechanical system. Ann. Phys. 527, 107–114 (2015).

Braginsky, V. B., Vorontsov, Y. I. & Thorne, K. S. Quantum nondemolition measurements. Science 209, 547–557 (1980).

Mallet, F. et al. Quantum state tomography of an itinerant squeezed microwave field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 220502 (2011).

Jähne, K. et al. Cavity-assisted squeezing of a mechanical oscillator. Phys. Rev. A 79, 063819 (2009).

Metelmann, A. & Clerk, A. Quantum-limited amplification via reservoir engineering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 133904 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIST and the DARPA QuASAR program. We thank M. A. Castellanos-Beltran and A. J. Sirois for valuable conversations and technical assistance, L. R. Vale for fabrication of the JPA, and A. W. Sanders for taking the SEM micrograph in Fig. 1c. J. B. Clark acknowledges the NRC for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.B.C. and J.D.T. designed the experiment and analysed the results. J.B.C. performed the measurements. F.L. assisted in the experimental set-up and fabricated the optomechanical circuit. J.A. designed the parametric amplifier. J.B.C. and J.D.T. wrote the manuscript, with significant comments from R.W.S. All authors provided experimental support and discussed the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary information (PDF 700 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clark, J., Lecocq, F., Simmonds, R. et al. Observation of strong radiation pressure forces from squeezed light on a mechanical oscillator. Nature Phys 12, 683–687 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3701

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3701

This article is cited by

-

Optomechanics for quantum technologies

Nature Physics (2022)

-

Unveiling bulk and surface radiation forces in a dielectric liquid

Light: Science & Applications (2022)

-

Squeezed-light-driven force detection with an optomechanical cavity in a Mach–Zehnder interferometer

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Broadband reduction of quantum radiation pressure noise via squeezed light injection

Nature Photonics (2020)

-

Bright squeezed light reduces back-action

Nature Photonics (2020)