Abstract

An electron gas in a one-dimensional periodic potential can be transported even in the absence of a voltage bias if the potential is slowly and periodically modulated in time. Remarkably, the transferred charge per cycle is sensitive only to the topology of the path in parameter space. Although this so-called Thouless charge pump was first proposed more than thirty years ago1, it has not yet been realized. Here we report the demonstration of topological Thouless pumping using ultracold fermionic atoms in a dynamically controlled optical superlattice. We observe a shift of the atomic cloud as a result of pumping, and extract the topological invariance of the pumping process from this shift. We demonstrate the topological nature of the Thouless pump by varying the topology of the pumping path and verify that the topological pump indeed works in the quantum regime by varying the speed and temperature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Topology manifests itself in physics in a variety of ways2,3,4, with the integer quantum Hall effect (IQHE) being one of the best-known examples in condensed matter systems. There, the Hall conductance of a two-dimensional electron gas is quantized very precisely in units of fundamental constants5. As discussed in the celebrated Thouless–Kohmoto–Nightingale–den Nijs paper6, this quantized value is given by a topological invariant, the sum of the Chern numbers of the occupied energy bands.

In 1983, Thouless considered a seemingly different phenomenon of quantum transport of an electron gas in an infinite one-dimensional periodic potential, driven in a periodic cycle1. This seems to be similar to the famous Archimedes screw7, which pumps water via a rotating spiral tube. However, whereas the Archimedes screw follows classical physics and the pumped amount of water can be changed continuously by tilting the screw, the charge pumped by the Thouless pump is a topological quantum number and not affected by a smooth change of parameters1. Interestingly, this quantization of pumped charge shares the same topological origin as the IQHE. The charge pumped per cycle can be expressed by the Chern number defined over a (1 + 1)-dimensional periodic Brillouin zone formed by quasimomentum k and time t. Although several single-electron pumping experiments have been implemented in nanoscale devices, such as quantum dots with modulated gate voltages8,9,10 or surface acoustic waves to create a potential periodic in time11, the topological Thouless pump, which should have the spatial periodicity to define the Bloch wavefunction as well as the temporal periodicity, has not been realized in electron systems.

In this Letter, we report a realization of Thouless’ topological charge pump by exploiting the controllability of ultracold atoms in an optical superlattice. Differently from recent realizations of topological bands in two (spatial or synthetic) dimensions12,13,14,15,16,17, our experiment explores the topology of a (1 + 1)-dimensional adiabatic process, in which a dynamically controllable one-dimensional optical superlattice is implemented following the proposal of ref. 18. Topological pumping is seen as a shift of the centre of mass (CoM) of an atomic cloud measured with in situ imaging. We extract the Chern number of the pumping procedure from the average shift of the CoM per pumping cycle. The topological nature of the pump is revealed by the clear dependence on the topology of the pumping trajectories in parameter space as to whether the trajectory is enclosing the degenerate point or not. Our work introduces a new experimental platform to study topological quantum phenomena in adiabatic driven systems.

In our experiments, an ultracold Fermi gas of ytterbium atoms 171Yb is prepared (see Methods) and loaded into a dynamically controlled optical superlattice. Specifically, we construct a stationary lattice (short lattice) with a period of 266 nm and a dynamical interferometric lattice (long lattice) with a period of 532 nm whose phase is stabilized and controlled by a Michelson interferometer (see Methods). As a result, these laser beams create the required18 time-dependent one-dimensional optical superlattice of the form

where d = 532 nm is the lattice constant of the superlattice, VS is the depth of the short lattice, VL the depth of the long lattice, and φ is the phase difference between the two lattices. In our experiments, VS and VL are controlled by the respective laser powers and φ by changing the optical path difference between the two interfering beams with a piezo-transducer (PZT)-mounted mirror, which enables us to sweep φ up to ∼11π, corresponding to more than ten pumping cycles. In the following, we use the lattice constant d as the unit of length and the recoil energy ER = h2/(8md2) as the unit of energy, where h denotes Planck’s constant and m is the atomic mass of 174Yb (see Methods).

We load 171Yb atoms into an array of one-dimensional optical superlattices, ensuring that they occupy the lowest energy band (see Supplementary Information 4), and slowly sweep φ over time. The lattice potential returns to its initial configuration whenever φ changes by π, thus completing a pumping cycle. Because the lattice potential is periodic both in space and time, one can define energy bands, the Bloch wavefunction |ψk(t)〉 = eikz |uk(t)〉, and corresponding topological invariants such as the Chern number ν in a k–t Brillouin zone:

where Ω(k, t) = i(〈∂tuk|∂kuk〉 − 〈∂kuk|∂tuk〉) is the Berry curvature (see Methods) and T the pumping period. We have ensured that the bandgap never closes during the whole pumping procedure, so ideally the atoms stay in the lowest band during the adiabatic pumping process. The phase sweep breaks time-reversal symmetry and the energy bands can acquire a non-zero Chern number ν. The shift of the CoM of the atomic cloud in such a topologically nontrivial band after one pumping cycle is simply given by νd.

The ability to tune all parameters of the lattice potential (1) independently in a dynamic way offers the opportunity to realize various pumping protocols. In the absence of the static short lattice, V (z, t) describes the simple sliding lattice which Thouless originally proposed1. Including the VS term, one realizes the double-well lattice illustrated in Fig. 1. A pictorial understanding of this alternative pumping process is provided by the tight-binding Rice–Mele model19,20,

where  (

( ) and

) and  (

( ) are fermionic annihilation (creation) operators in the two sublattices of the ith unit cell, J ± δ is the tunnelling amplitude within and between unit cells, and Δ denotes a staggered on-site energy offset, as shown in Fig. 1a. We ignore the spin degree of freedom because we can neglect the interaction between the two spin components owing to a very small s-wave scattering length21.

) are fermionic annihilation (creation) operators in the two sublattices of the ith unit cell, J ± δ is the tunnelling amplitude within and between unit cells, and Δ denotes a staggered on-site energy offset, as shown in Fig. 1a. We ignore the spin degree of freedom because we can neglect the interaction between the two spin components owing to a very small s-wave scattering length21.

a, Schematic of the Rice–Mele model. b, A pumping cycle sketched (qualitatively) in δ–Δ space. c. Schematic of the continuous Rice–Mele (cRM) pumping sequence. The pink shaded packet indicates the wavefunction of a particular atom initially localized at the unit cell i. The wavefunction shifts to right as the pumping proceeds and the atom moves to unit cell i + 1 after one pumping cycle. The blue dashed curve and the green arrow indicate the harmonic confinement (not in scale) and an initial hole, respectively.

Figure 1c shows the schematics of our ‘continuous Rice–Mele’ (cRM) pumping sequence. Sweeping the phase linearly in time as φ(t) = πt/T, the hopping amplitudes and on-site energies are modulated periodically. Our ab initio calculation shows that the cRM pumping scheme used in the experiment is topologically equivalent to the Rice–Mele model for atoms that reside in the lowest energy band, because the Chern numbers are the same (see Supplementary Information 3). In the following, we will thus use the tight-binding Rice–Mele Hamiltonian to simplify the discussion of the pumping sequence as a closed trajectory in the δ–Δ parameter plane (Fig. 1b). Note that, as shown in Fig. 1c, our system has metallic edge states and thermal holes due to the combination of the trapping potential and finite temperature. We estimate the filling of the lattice is typically ∼0.7 for each spin at the centre of the trap. However, in the case of our deep optical lattice systems, the shift of the CoM of the atomic cloud still constitutes a quantized shift in spite of these thermal and finite size effects (see Supplementary Information 2).

Figure 2 shows the main results of our pumping experiments. Our stable absorption imaging system with a charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera enables us to accurately measure the shift of the CoM of the atomic cloud after several pumping cycles (see Supplementary Information 5), as shown in Fig. 2a, b. The period T is fixed to 50 ms for the results shown in Fig. 2. One can clearly recognize the sizable CoM shift along the z-direction. We plot the in situ CoM positions of the atomic cloud after a few pumping cycles in Fig. 2d. The averaged CoM shift per cycle 〈z(t) − z(0)〉/(td) of the cRM pumping with (VS, VL) = (20,30)ER is evaluated to be 0.94(7) for t ≤ 6T. This provides a direct measurement of the Chern number of the occupied energy band, which is consistent with the ideal value ν = 1. As a comparison, the observed average CoM shift per cycle of a sliding lattice (VS, VL) = (0,40)ER is 0.94(4), which is again close to the ideal value of ν = 1. Classically it is fairly intuitive that the sliding lattice is able to transfer atoms because the potential minima are moving in space. However, even though the potential minima of the cRM pump (VS, VL) = (20,30)ER are not moving in space, as shown in Fig. 1c, the pumping is topologically equivalent because of the same Chern number of the occupied band. The cRM lattice has the same ability to transfer atoms residing in the lowest energy band, even though the pumping is achieved by a sequence of quantum tunnelling events between the double wells (see Supplementary Information 4). We attribute the saturating behaviour of the cRM pumping for t > 6T to the effect of the harmonic confinement, whose variation can be comparable to the bandgap for a large CoM shift22 (see Supplementary Information 6).

a,b, In situ absorption images on the CCD before and after 10 cRM pumpings, respectively. c, One-dimensional optical densities (integrated along the x axis) before pumping (red circles, same data as a) and after 10 cRM pumping (blue diamonds, same data as b). d, The centre of mass (CoM) of the atomic cloud after up to ten pumping cycles. Red circles and blue open diamonds indicate the CoM shift of the sliding lattice and the cRM pumping lattice, respectively. Error bars denote the standard deviation of five independent measurements.

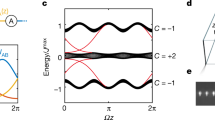

A striking feature of our pump is its topological nature. In particular, the pumped amount in the Rice–Mele model23,24 is directly related to the topology of the trajectory in the δ–Δ plane. It depends only on the winding number w of the trajectory that encloses the origin δ = Δ = 0 (see Supplementary Information 3). Note that electron pumping in restricted nano-devices8,9,10,11 is not topological, because in that case the amount of the charge pumped per cycle instead depends on the area of the enclosed parameter space25, which is the geometry but not the topology of the trajectory. To highlight the topological nature of Rice–Mele pumping, we investigate four distinct pumping sequences with trajectories shown schematically in Fig. 3b–e. In Fig. 3a, we plot the CoM shifts of two cRM pumping schemes with (VS, VL) = (20,30)ER (Fig. 3b, e) and two amplitude-modified cRM pumping schemes (Fig. 3c, d). Evidently, the sequence which does not wind around the origin (Fig. 3d) results in no pumping, and those with winding trajectories (Fig. 3b, c, e) result in finite pumping. Also the forward cRM pumping (Fig. 3b) and the amplitude-modified cRM pumping (Fig. 3c) exhibit almost the same pumping behaviour, although the area enclosed by the trajectory of Fig. 3c is actually smaller than that of Fig. 3b. This is direct evidence of the topological nature of the pump. Note that the band structure in the k–t space of the nontrivial pumping sequence (Fig. 3c) is identical to that of the trivial pumping (Fig. 3d). However, the Berry curvature and the Chern number of the lowest band are different. This highlights the fact that the pumped charge is a topological quantity, which depends on the wavefunction but not on the band dispersions. Furthermore, we also performed the cRM pumping with a negative sweep of the phase φ(t) = −πt/T, which corresponds to an opposite winding in the δ–Δ plane, and the cloud is pumped in the opposite direction even though the band dispersion remains identical to that of the forward sweep pumping (Fig. 3e).

a, Charge pumped during a simple cRM pumping (b), topologically nontrivial pumping (c), topologically trivial pumping (d), and negative sweep cRM pumping (e). The vertical error bars denote the standard error of the mean of ten CoM measurements. b–e, Schematic pumping sequences in the δ–Δ plane (top), the corresponding band structures in the k–t Brillouin zone (middle), and the Berry curvatures of the pumping cycles (bottom). The indices w in the top figures indicate the winding number of each trajectory around the origin. δ and Δ are in units of the recoil energy ER.

A crucial requirement of the topological Thouless pump is adiabaticity, requiring that the bandgap never closes during the pumping process and that the atoms always remain in the lowest energy band. Figure 4a shows the pumping period dependence of the cRM pumping with depths of (VS, VL) = (30,30)ER. The data suggests that the averaged CoM shift per cycle reaches its ideal values if the pumping period T is longer than ∼30 ms—that is, a cycle period of T > 30 ms is long enough to satisfy the adiabatic condition in this lattice potential. This can be understood by considering Landau–Zener transitions to the higher band. The instantaneous energy gap D(t) = E2 − E1 changes in time, as shown in the inset of Fig. 4a. The diabatic transition probability P is determined by the minimum bandgap Dmin and the maximum bandgap Dmax through the Landau–Zener formula P = e−2πΓ, where Γ = (Dmin/2)2/(ℏ(d/dt)D(t)). In our case, Dmin = 1.6ER and Dmax = 20ER. Because the energy sweep speed dD/dt is of the order of 8Dmax/T, we find that 2πΓ ∼ T/(6 ms), which is consistent with the observed result.

a, The averaged CoM shift per cycle (averaged after two cycles) versus the pumping period T. The inset shows instantaneous band maxima E1 of the first band and minima E2 of the second band for (VS, VL) = (30,30)ER. The pumped amount saturates as the pumping speed slows down. The dotted curve shows an exponential fit with time constant 5.1(9) ms. The error bars denote the 1σ confidence bound derived from thirty CoM measurements. b. Finite-temperature effect in the cRM pumping. The pumped amount (averaged after five cycles) approaches the ideal value as the temperature decreases. The vertical error bars denote the 1σ confidence bound derived from ten CoM measurements. The horizontal axis is the initial temperature in the FORT before lattice loading, evaluated from the Fermi–Dirac fitting in the degenerate regime (T/TF ≲ 0.5) and from the Gaussian fitting in the thermal regime. The horizontal error bar indicates the standard deviation of five independent temperature measurements.

We next check the temperature dependence of our pump. Figure 4b shows the pumped amount as a function of the temperature of the gas before loading into the lattice with depths of (VS, VL) = (25,30)ER. The temperature is tuned by changing the sympathetic evaporative cooling condition while keeping the same number of 171Yb atoms. One can see that pumping reaches the ideal value at the lowest loading temperature in the far-off-resonant trap (FORT) of 33(4) nK, which corresponds to 0.24(4)TF, where TF is the Fermi temperature. Assuming an adiabatic lattice loading, we estimate that the temperature of atoms in the optical superlattice could be 65(15) nK for this lowest loading temperature. Although the temperature given in Fig. 4b is not the temperature in the lattice, but rather that before lattice loading, the observed temperature dependence exhibits similar behaviour to that discussed in ref. 18; pumping efficiency reaches its ideal value once the temperature becomes lower than the minimum bandgap of 2.4ER (= 120 nK) for these lattice depths.

Having demonstrated topological Thouless pumping using a flexible optical superlattice set-up, the scheme can be extended to even more novel set-ups. For example, by choosing a special lattice laser frequency, one can create a spin-dependent superlattice26 which realizes Z2-spin pumping27, a counterpart of Z2 topological insulators. Another possibility is to change the ratio of the long lattice and short lattice wavelengths by tuning the angle of the interferometric lattice, which realizes a superlattice with incommensurate ratios and the Aubry–André model28 with fractional pumping29 and anomalous pumping30. Furthermore, introducing interaction effects is feasible and will create opportunities for the experimental exploration of the interplay of topological quantum phenomena and interaction and correlation effects.

Note added in proof: Recently, we became aware of similar work carried out by Lohse et al. 31 observing topological Thouless pumping with bosonic atoms in the Mott insulator state.

Methods

Preparation of a degenerate Fermi gas of 171Yb.

Because171Yb atoms have a very short s-wave scattering length of −0.15 nm (ref. 21), we use sympathetic evaporative cooling with 173Yb atoms to obtain the degenerate Fermi gas of 171Yb (ref. 32). After collecting Yb atoms in a magneto-optical trap using the intercombination transition (556 nm), the two isotopes are loaded into a crossed far-off-resonant trap (FORT) with 532 nm light. Sympathetic evaporative cooling is performed by continuously decreasing the FORT trap depth. After blowing away the 173Yb atoms by means of a 556 nm laser which is resonant only for 173Yb, we obtain a pure degenerate gas of 171Yb atoms with two hyperfine spin components of |F = 1/2, mF = ±1/2〉. The number of atoms for each spin is typically 9(1.5) × 103 for Figs 2 and 4b, and 6(1.5) × 103 for Figs 3 and 4a. A typical temperature in the FORT before lattice loading is T/TF = 0.26(8) at the end of the evaporation, with the trap frequencies of the FORT of (ωx′, ωy′, ωz)/2π = (170,42,153) Hz, where the x′- and y′- axes are tilted from the lattice axes (x and y) by 45°.

Set-up for the optical superlattice.

Our one-dimensional optical superlattice set-up is a part of our optical Lieb lattice system33. To stabilize the phase φ of the interfering 532-nm-spacing optical lattice (long lattice) we construct a Michelson interferometer with a frequency-stabilized 507 nm laser, whose optical paths are overlapped with the interfering lattice beams until separated from the lattice beams by dichroic mirrors before entering the experimental chamber. The 507 nm laser beams are retro-reflected to form the interferometer just after the separation. We can control the phase φ by tuning the PZT of the retro-reflection mirror of the z-axis 507 nm laser, keeping stabilization of the optical path lengths of the lattice and 507 nm beams by means of another PZT-mounted mirror in the common path as long as the phase sweep speed is less than 0.5π rad ms−1. The short-term stability of the phase φ is estimated to be 0.007π. A phase drift of typically 0.05π per hour is not a problem because the pumping depends only on the phase difference before and after pumping. The nonlinearity of the PZT and the relative phase φ between the long lattice and the short lattice are calibrated by means of the matter wave interference pattern of a Bose–Einstein condensate (BEC) of 174Yb atoms released from the superlattice. The depths of optical lattices are also calibrated by means of a pulsed lattice with the BEC of 174Yb.

Calculations of the band structure and Chern number.

To predict the pumped charge of the experimental pumping protocols, we calculate the band structures and the Chern numbers of the one-dimensional Hamiltonian H(z, t) = −ℏ2∇2/(2m) + V (z, t). The band structure is obtained by solving H(z, t) |ψk(t)〉 = E(k, t) |ψk(t)〉 in a plane wave basis. The Chern number is then calculated as

where Ω(k, t) = ∂tAk − ∂kAt is the Berry curvature and At(k) = i〈uk(t)|∂t(k)|uk(t)〉 is the Berry connection calculated using the periodic part of the Bloch wavefunction |uk(t)〉 = e−ikz |ψk(t)〉.

References

Thouless, D. J. Quantization of particle transport. Phys. Rev. B 27, 6083–6087 (1983).

Mermin, N. D. The topological theory of defects in ordered media. Rev. Mod. Phys. 51, 591–648 (1979).

Thouless, D. J. Topological Quantum Numbers in Nonrelativistic Physics (World Scientific, 1998).

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Klitzing, K. v., Dorda, G. & Pepper, M. New method for high-accuracy determination of the fine-structure constant based on quantized Hall resistance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 494–497 (1980).

Thouless, D. J., Kohmoto, M., Nightingale, M. P. & den Nijs, M. Quantized Hall conductance in a two-dimensional periodic potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 405–408 (1982).

Altshuler, B. L. & Glazman, L. I. Pumping electrons. Science 283, 1864–1865 (1999).

Switkes, M., Marcus, C. M., Campman, K. & Gossard, A. C. An adiabatic quantum electron pump. Science 283, 1905–1908 (1999).

Blumenthal, M. D. et al. Gigahertz quantized charge pumping. Nature Phys. 3, 343–347 (2007).

Kaestner, B. et al. Single-parameter nonadiabatic quantized charge pumping. Phys. Rev. B 77, 153301 (2008).

Shilton, J. M. et al. High-frequency single-electron transport in a quasi-one-dimensional GaAs channel induced by surface acoustic waves. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 8, L531–L539 (1996).

Aidelsburger, M. et al. Realization of the Hofstadter Hamiltonian with ultracold atoms in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 185301 (2013).

Miyake, H., Siviloglou, G. A., Kennedy, C. J., Burton, W. C. & Ketterle, W. Realizing the Harper Hamiltonian with laser-assisted tunneling in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 185302 (2013).

Jotzu, G. et al. Experimental realization of the topological Haldane model with ultracold fermions. Nature 515, 237–240 (2014).

Aidelsburger, M. et al. Measuring the Chern number of Hofstadter bands with ultracold bosonic atoms. Nature Phys. 11, 162–166 (2015).

Mancini, M. et al. Observation of chiral edge states with neutral fermions in synthetic Hall ribbons. Science 349, 1510–1513 (2015).

Stuhl, B. K., Lu, H.-I., Aycock, L. M., Genkina, D. & Spielman, I. B. Visualizing edge states with an atomic Bose gas in the quantum Hall regime. Science 349, 1514–1518 (2015).

Wang, L., Troyer, M. & Dai, X. Topological charge pumping in a one-dimensional optical lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 026802 (2013).

Rice, M. J. & Mele, E. J. Elementary excitations of a linearly conjugated diatomic polymer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 1455–1459 (1982).

Atala, M. et al. Direct measurement of the Zak phase in topological Bloch bands. Nature Phys. 9, 795–800 (2013).

Kitagawa, M. et al. Two-color photoassociation spectroscopy of ytterbium atoms and the precise determinations of s-wave scattering lengths. Phys. Rev. A 77, 012719 (2008).

Qian, Y., Gong, M. & Zhang, C. Quantum transport of bosonic cold atoms in double-well optical lattices. Phys. Rev. A 84, 013608 (2011).

Xiao, D., Chang, M.-C. & Niu, Q. Berry phase effects on electronic properties. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1959–2007 (2010).

Shen, S.-Q. Topological Insulators: Dirac Equation in Condensed Matters (Springer, 2013).

Brouwer, P. W. Scattering approach to parametric pumping. Phys. Rev. B 58, R10135–R10138 (1998).

Mandel, O. et al. Coherent transport of neutral atoms in spin-dependent optical lattice potentials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 010407 (2003).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Time reversal polarization and a Z2 adiabatic spin pump. Phys. Rev. B 74, 195312 (2006).

Aubry, S. & André, G. Analyticity breaking and Anderson localization in incommensurate lattices. Ann. Isr. Phys. Soc. 3, 133–140 (1980).

Marra, P., Citro, R. & Ortix, C. Fractional quantization of the topological charge pumping in a one-dimensional superlattice. Phys. Rev. B 91, 125411 (2015).

Wei, R. & Mueller, E. J. Anomalous charge pumping in a one-dimensional optical superlattice. Phys. Rev. A 92, 013609 (2015).

Lohse, M. et al. A Thouless quantum pump with ultracold bosonic atoms in an optical superlattice. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nphys3584 (2015).

Taie, S. et al. Realization of a SU(2) × SU(6) system of fermions in a cold atomic gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 190401 (2010).

Taie, S. et al. Coherent driving and freezing of bosonic matter wave in an optical Lieb lattice. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500854 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank N. Kawakami, S. Fujimoto, J. Ozaki, T. Fukui, I. Maruyama, Y. Hatsugai and S. Nakamura for valuable discussions and A. Sawada for experimental assistance. This work was supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research of JSPS (No. 25220711, No. 26247064, No. 24-1698), and the Impulsing Paradigm Change through Disruptive Technologies (ImPACT) Program. L.W. and M.T. were supported by ERC Advanced Grant SIMCOFE and by the Swiss National Science Foundation through the National Center of Competence in Research Quantum Science and Technology QSIT. L.W. and M.T. acknowledge X. Dai for collaborations on the related topic.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.N. and T.T. carried out experiments and the data analysis. S.T. conceived the experimental techniques for the superlattice. T.I. and H.O. contributed to building the superlattice set-up. L.W. carried out the theoretical calculations. Y.T. conducted the whole experiment. All the authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary information (PDF 2997 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nakajima, S., Tomita, T., Taie, S. et al. Topological Thouless pumping of ultracold fermions. Nature Phys 12, 296–300 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3622

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3622

This article is cited by

-

Laughlin charge pumping in a quantum anomalous Hall insulator

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Quantized fractional Thouless pumping of solitons

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Thouless pumping and topology

Nature Reviews Physics (2023)

-

Topological invariants for anomalous Floquet higher-order topological insulators

Frontiers of Physics (2023)

-

Quantum simulations with ultracold atoms in optical lattices: past, present and future

Journal of the Korean Physical Society (2023)