Abstract

Electrons incident from a normal metal onto a superconductor are reflected back as holes—a process called Andreev reflection1,2,3. In a normal metal where the Fermi energy is much larger than a typical superconducting gap, the reflected hole retraces the path taken by the incident electron. In graphene with low disorder, however, the Fermi energy can be tuned to be smaller than the superconducting gap. In this unusual limit, the holes are expected to be reflected specularly at the superconductor–graphene interface owing to the onset of interband Andreev processes, where the effective mass of the reflected holes changes sign4,5. Here we present measurements of gate-modulated Andreev reflections across the low-disorder van der Waals interface formed between graphene and the superconducting NbSe2. We find that the conductance across the graphene–superconductor interface exhibits a characteristic suppression when the Fermi energy is tuned to values smaller than the superconducting gap, a hallmark for the transition between intraband retro Andreev reflections and interband specular Andreev reflections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Andreev reflection (AR) is a process transferring charges from a normal metal (N) into a superconductor (SC; refs 1,2,3). When an NS interface is biased with an energy eVns above the Fermi energy ɛF, an electron can only be injected into the SC gap Δ, if a hole is reflected back with an energy of eVns below ɛF, creating a Cooper pair at the Fermi level. For a straight N/SC interface, the momentum conservation along the boundary must be conserved. Thus the incidence angle of an incoming electron, θinc, and the reflected angle of a hole, θref, have a simple relation pe sinθinc = ph sinθref, where pe and ph are the total momentum of the electron and hole, respectively. In the limit ɛF ≫ Δ, which holds for a typical NS junction, the reflected hole is metal-like and remains in the conduction band of the normal metal, and therefore necessarily carries the opposite sign of the mass as compared to the electron. To conserve the momentum, the hole reflects back along a path of the incident electron, exhibiting nearly perfect retro-AR, with θref ≈ −θinc (refs 6,7,8).

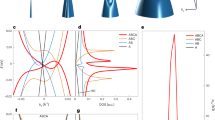

If, however, the Fermi energy can be tuned such that ɛF ≤ Δ, a completely different kind of AR is expected. In this case the energy difference, 2eVns, provided by the AR process can result in the reflected hole appearing in the valence band rather than the conduction band. The reflected semiconductor-like hole now has the same mass sign as the incident electron, and therefore, according to momentum conservation, travels in the same direction along the interface (θref > 0 in Fig. 1). In the ultimate limit of ɛF = 0, the angle of reflection equals the angle of incidence θref = θinc—a process called specular reflection4,5. The condition for specular-AR is satisfied whenever Δ > eVns > ɛF (Fig. 1a right panel), and is therefore predicted to be observable when the normal metal in the N/SC junction consists of a zero-gap semiconductor (ZGS), and the Fermi energy is tuned close to the charge neutrality point (CNP) where the conduction band and valence band meet.

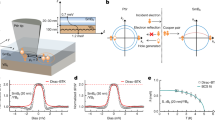

a, Schematics of the AR processes at a normal metal/SC (left) and a zero-gap semiconductor/SC interface (right). An electron from the CB with a total energy of ɛF + eVns is reflected as a hole with an energy ɛF − eVns, forming a Cooper pair at ɛF in the SC. For large ɛF the hole remains in the CB, resulting in an intraband retro-reflection process. For small enough ɛF the hole undergoes an interband transition into the VB, resulting in specular reflections. b, Top: colour-enhanced optical image of the hBN/BLG device before the transfer of the NbSe2 flake (marking its final position). The NbSe2 and the hBN/BLG stack form an electrically coupled overlap region. Bottom left: schematic diagram of the vertical cross-section of the vdW stack. Bottom right: sketch of the final device on top of a 300 nm SiO2/Si back gate. c, Inset: temperature dependence of the differential resistance dV/dI versus bias current Isd across the BLG/NbSe2 interface at Vbg = −50 V. Strong variations of dV/dI appear below the NbSe2 value of Tc ∼ 7 K. Main: normalized conductance G1.7 K/G10 K versus Vns. The characteristic double-peak lineshape arises from ARs in the limit ɛF ≫ Δ.

Graphene provides an ideal platform to exhibit both intraband and interband AR. Its two-dimensional nature and ZGS properties enable a crossover to be induced between intraband and interband AR by tuning ɛF through the electric field effect9,10,11. However, accessing the regime ɛF ∼ Δ, a necessary condition to realize the interband AR, has been technically challenging. In typical graphene samples on a SiO2 substrate, strong potential fluctuations up to δɛF ∼ 50 meV have been typically observed owing to the presence of charged impurities12. This value is much larger than Δ in a typical SC. The recent progress in producing suspended13 and hexagonal boron nitride (hBN)-supported graphene samples14 has now allowed these fluctuations to be greatly reduced down to δɛF ∼ 5 meV (ref. 15). Despite the steady experimental progress that has been made in contacting graphene with various superconducting metals16,17,18,19,20, including recent work on the edge contact on graphene21,22, fabricating transparent SC contacts on graphene channels with extremely low inhomogeneity has yet to be realized.

In this letter we employ a novel non-invasive approach to fabricate N/SC interfaces with an unprecedented energy resolution close to the CNP. For this purpose we electronically couple (see Supplementary Information for details of the method) a high-mobility hBN/bilayer graphene (BLG) device and a 20–100 nm thin NbSe2 flake. NbSe2 is a van der Waals (vdW) SC with a critical temperature Tc ∼ 7 K and a large Δ ∼ 1.2 meV (refs 23,24,25; Fig. 1b). We use the dry-vdW transfer technique and a current annealing method14,26 to achieve ohmic interfaces between graphene and NbSe2 with a low junction resistance (see Supplementary Information). In this experiment, we chose BLG rather than single-layer graphene to minimize δɛF near the CNP. Owing to the larger density of states of BLG near the CNP, a smaller δɛF can be obtained in BLG given the similar level of substrate-induced inhomogeneity. The devices were fabricated on heavily degenerated Si substrates topped with 300 nm SiO2, where a back-gate voltage Vbg is applied to tune the ɛF value of the BLG channel.

We characterize the electronic transport properties across the vdW N/SC junction by measuring the differential resistance dV/dI as a function of the channel current Isd. The inset of Fig. 1c shows typical traces for a high back-gate voltage Vbg = −50 V that corresponds to a representative condition ɛF ≫ Δ. We observe that the dV/dI(Isd) traces become increasingly nonlinear for temperatures T < Tc. To resolve these features better, we divide traces taken below and above Tc (here at T = 1.7 K and T = 10 K) and obtain the normalized differential conductanceG1.7 K/G10 K = (dV/dI10 K)/(dV/dI1.7 K). Figure 1c shows G1.7 K/G10 K as a function of the voltage drop across the N/SC junction Vns, estimated by considering the BLG channel resistance (Supplementary Information). The most salient feature of the resulting G1.7 K/G10 K(Vns) curve is a conductance dip around zero bias with two pronounced conductance peaks at |Vns| ∼ ±1.2 mV. The position of these peaks is consistent with the value of . Later, we will show that this lineshape is characteristic for typical N/SC junctions with ɛF ≫ Δ and can be explained in terms of intraband retro-ARs (refs 6,7,8,27).

The ability to tune ɛF enables us to investigate the characteristic AR signal at the continuous transition from large to small ɛF. The left panel of Fig. 2a shows the characteristic longitudinal resistance Rxx of the BLG channel versus Vbg. An upper bound of δɛF < 1 meV is estimated from the full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the Rxx(Vbg) peak13,14,15, demonstrating that the condition ɛF < Δ can be realized in this sample. The indirect estimates of δεF from the FWHM, however, are typically found to be much higher than from more direct measurements of δεF by scanning gate12 or scanning tunnelling microscopy15, allowing one to assume a much smaller spatial energy variation in our sample. The right panel of Fig. 2a shows simultaneous measurements of G1.7 K/G10 K as a function of both the voltage drop at the N/SC interface Vns and Vbg. For large ɛF, |Vbg| > 2 V, G1.7 K/G10 K(Vns) exhibits a similar behaviour to that described in Fig. 1c, showing the characteristic conductance dip around the zero-bias condition Vns = 0. However, near the CNP, for |Vbg| < 2 V, the G1.7 K/G10 K(Vns) traces exhibit marked variations. These result in dispersing conductance dip features that approximately follow the relation |eVns| ∼ |ɛF| (Fig. 2c, top) and form a distinctive cross-like lineshape around the CNP point (Fig. 2a).

a, Left: Rxx versus Vbg, showing the characteristic channel resistance peak at the CNP with a FWHM of δVbg ∼ 0.6 V, suggesting an upper bound of δɛF < 1 meV. Right: colour map of the normalized differential conductance G1.7 K/G10 K as a function of Vns and Vbg for the inner gap region |eVns| < Δ. b, Colour map of the theoretically obtained normalized differential conductance Gns/Gnn versus Vns and ɛF for the equivalent energy ranges used in the experimental data. The gate tunability of BLG allows the conductance changes to be probed continuously from the upper limit |ɛF| ≫ Δ to the lower limit |ɛF| ∼ Δ. The zero-bias dip lineshape at large ɛF is continuously transformed into a diagonal cross-like lineshape close to the CNP. c, Curves of G1.7 K/G10 K(Vns) (top) and Gns/Gnn(Vns) (bottom) for various fixed values of Vbg and the corresponding values of ɛF. Conductance dips for eVns ∼ ɛF appear in the low-energy regime |ɛF| < Δ.

To explain these experimental findings at the crossover from the upper to the lower ɛF limit, we develop a theoretical model based on the Bogoliubov–de Gennes equations and the Blonder–Tinkham–Klapwijk (BTK) formalism for the conductance across the BLG/SC interface Gns at T = 0 K. We also compute the normal conductance Gnn for T > Tc (∼10 K) (see Supplementary Information for details). Figure 2b shows the resulting normalized conductance Gns/Gnn as a function of ɛF and Vns for energy ranges comparable to those in the experimental data. The theoretical model demonstrates qualitatively good agreement with the experimentally obtained normalized conductance in Fig. 2a. Conductance lineshapes in both regimes (Fig. 2c, bottom), the zero-bias conductance dips for |ɛF| ≫ Δ and the dispersing conductance dips for |ɛF| ∼ Δ, are matched qualitatively and quantitatively with the theory. The slight asymmetry of the theoretical conductance around zero bias is due to the shift of the Fermi energy in the BLG channel when a bias voltage is applied across the N/SC junction.

Further quantitative comparison between the experiment and the theoretical model in the small-energy regime |ɛF| ∼ Δ can be performed by re-plotting the experimental G1.7 K/G10 K map as a function of ɛF and Vns (Fig. 3a—see Supplementary Information for the conversion scheme). In both graphs, one can identify four regions of enhanced conductance (coloured blue): two of them for |ɛF| > |eVns| and two for |ɛF| < |eVns| . These regions are separated from each other by connected regions of reduced conductance (coloured red) that approximately follow the dependence |ɛF| ∼ |eVns|, forming diagonal lines that are roughly symmetrically arranged with respect to ɛF = eVns = 0 in the conductance maps. Several representative line cuts, showing G1.7 K/G10 K(ɛF), clearly exhibit similar features for both experimental and theoretical traces, with good quantitative agreement for the positions of the conductance dips (Fig. 3b).

a, Experimental G1.7 K/G10 K and theoretical Gns/Gnn colour maps as a function of Vns and ɛF in the limit |ɛF| ∼ Δ. A continuous region of lower conductance (red) that is defined for |ɛF| ∼ |eVns| (white dashed lines) subdivides the map into four disconnected regions of comparatively high conductances (blue). In the regions where |ɛF| > |eVns| the ARs are of the retro type, whereas in the regions where |ɛF| < |eVns| the ARs are of the specular type. b, Experimental G1.7 K/G10 K(ɛF) and theoretical Gns/Gnn(ɛF) line-traces demonstrate the evolution of the conductance dips (red arrows) with varying Vns. c, Schematics of the AR process for BLG at the crossover from intraband to interband ARs. With decreasing ɛF at a fixed Vns the AR hole moves from the CB to the VB. The crossover point where the hole is reflected onto the CNP is defined by ɛF = eVns. d, Excitation spectrum ɛ(px) = eVns for a fixed ɛF < Δ. With an increasing excitation voltage Vns, the momentum px of the reflected hole increases continuously from negative to positive values, passing through zero when ɛF = eVns. Note that the quasi-particle excitation spectrum depends only on px, as py is conserved during the AR process. e, Schematics of the reflection angles of AR holes in the various energy limits. Starting from perfect intraband retro-reflections in the high-ɛF limit, θref increases continuously towards −π/2 asɛF is lowered. At the crossover point separating intraband and interband ARs, ɛF = eVns, θref exhibits a jump to π/2, which eventually results in perfect interband specular reflections (θref = θinc) when ɛF = 0.

The various features observed in the conductance map can be explained by analysing the microscopic processes for different ɛF (Fig. 3c). ARs for SLG and BLG involve intervalley processes due to the time reversal symmetry of the backwards motion of the reflected hole4,16,17,28. Therefore, for ɛF > eVns, an electron in the K-valley of the CB with an energy of ɛF + eVns is reflected as a hole in the K′-valley of the CB with an energy ɛF − eVns > 0. This intraband AR process gives rise to a relatively high conductance, analogous to ARs in normal metals in the limit ɛF ≫ Δ. When ɛF decreases, however, the phase space for the reflected hole is decreased, resulting in a decreasing conductance. This effect culminates in a minimum in conductance at the condition ɛF = eVns, where the hole is at the CNP and intraband ARs cease to exist. For ɛF < eVns the hole undergoes an interband transition into the VB and the conductance again increases.

This non-monotonic conductance change as a function of ɛF can be quantitatively explained by the existence of a critical angle  (Supplementary Information) that allows the AR process to happen only for electrons that are incident at θinc ≤ θc. In the limit of the intraband AR (ɛF ≫ eVns) and the interband AR (ɛF ≪ eVns), θc ≈ π/2, and thus most electrons undergo AR processes resulting in a high conductance. However, for ɛF ∼ eVns, the critical angle approaches zero. If we assume a distribution of angles for the incident electrons, those outside of the critical angle will be reflected normally and only those arriving at near normal incidence will undergo AR processes, resulting in an overall suppressed conductance across the junction. For ɛF = eVns, θc = 0, and no electrons can enter the SC. The resulting conductance minima hence mark the exact crossover points between intraband and interband ARs.

(Supplementary Information) that allows the AR process to happen only for electrons that are incident at θinc ≤ θc. In the limit of the intraband AR (ɛF ≫ eVns) and the interband AR (ɛF ≪ eVns), θc ≈ π/2, and thus most electrons undergo AR processes resulting in a high conductance. However, for ɛF ∼ eVns, the critical angle approaches zero. If we assume a distribution of angles for the incident electrons, those outside of the critical angle will be reflected normally and only those arriving at near normal incidence will undergo AR processes, resulting in an overall suppressed conductance across the junction. For ɛF = eVns, θc = 0, and no electrons can enter the SC. The resulting conductance minima hence mark the exact crossover points between intraband and interband ARs.

We can now connect these processes with the corresponding changes in θref (Fig. 3d, e). The dispersion relation E(px, py) of BLG is shown in Fig. 3d, where px and py are momenta perpendicular and parallel to the N/SC interface, respectively. Considering that the parallel momentum py is conserved in the process4,5, the excitation spectrum for ARs ɛ ≡ eVns = |E − ɛF| can be expressed by a function of only px. Depending on the magnitude of the energy of the incident CB electron (assuming that it is in the K-valley) relative to ɛF, we can then relate the reflection process to three different scenarios: the first, with Andreev-reflected CB holes (normal AR); the second, in which all CB electrons are normally reflected (no AR); and the third, yielding Andreev-reflected VB holes (specular-AR), all in the K′-valley. For small eVns ≪ ɛF, px of the incident electron and the intraband reflected CB hole is almost unchanged. Because a CB hole has a negative mass, its negative px and the conserved py provide an overall direction of motion that retraces that of the incident electron (that is, the first scenario above). As Vns grows, px of the reflected hole increases, translating into a larger θref, that ultimately becomes π/2 when ɛF = eVns and px = 0. As Vns grows further, so that eVns > ɛF, the incident electron is reflected as an interband VB hole, which has a positive mass and a positive px that is opposite to the sign of px of the incident electron. Whereas the simultaneous sign changes of the mass and of px have no effect on the motion in the x-direction, the sign change of the mass abruptly reverses the motion in the y-direction by 180° owing to the conservation of py, as described in the third scenario above. For the ultimate limits ɛF ≫ Δ and ɛF = 0 one obtains perfect retro-reflections and specular reflections, respectively, with varying angles for intermediate energy scales and a discontinuous jump at eVns = ɛF. Summarizing this discussion, the conductance maps in Fig. 3a can now be used as phase diagrams separating regions of retro-AR, where |ɛF| > |eVns|, and specular-AR, where |ɛF| < |eVns| .

Although our experimental findings are in good qualitative and quantitative agreement with the presented theory it is important to discuss possible deviations from it and rule out competing mechanisms. Most notably, the BLG band structure is renormalized when subjected to a transverse electric field and opens up a band gap11. In our measurements an energy gap would manifest itself in a diamond-shaped region of suppressed conductance around zero energy, which is distinctly different from the observed cross-like shape that shows a dispersion following the relation |eVns| ∼ |εF| . Although we do observe a small region of reduced conductance around zero energy, the scale of these features is much smaller than the SC gap Δ. Indeed, we estimate the electric-field-induced gap for back-gated devices not to be bigger than 0.4 meV for an applied Vbg = 0.75 V (ref. 11; corresponding to εF = Δ ∼ 1.2 meV). For such a small gap, interband transitions are still possible and specular-ARs can take place at slightly higher energies. Although additional deviations from the theory can also be attributed to imperfections due to a realistically broadened N/SC interface, inelastic scattering at finite temperatures, the presence of small potential fluctuations and a slightly renormalized BLG band structure11, we can rule these out as key mechanisms for the observed features.

In conclusion our observation of gate-tunable transitions between retro- and specular-ARs opens a new route for future experiments that could employ the gate control of θref, which can be continuously and independently altered with Vbg and Vns. Most importantly, our findings help to draw a more general picture of the exact physical processes underlying ARs.

References

Andreev, A. F. The thermal conductivity of the intermediate state in superconductors. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 19, 1228–1231 (1964).

DeGennes, P. G. Superconductivity of Metals and Alloys (Benjamin, 1966).

Tinkham, M. Introduction to Superconductivity (McGraw Hill, 1996).

Beenakker, C. W. J. Specular Andreev reflection in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 067007 (2006).

Beenakker, C. W. J. Colloquium: Andreev reflection and Klein tunneling in graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1337–1354 (2008).

Klapwijk, T. M. Proximity effect from an Andreev perspective. J. Supercond. 17, 593–611 (2004).

Pannetier, B. & Courtois, H. Andreev reflection and proximity effect. J. Low Temp. Phys. 118, 599–615 (2000).

Blonder, G. E., Tinkham, M. & Klapwijk, T. M. Transition from metallic to tunneling regimes in superconducting microconstrictions: Excess current, charge imbalance, and supercurrent conversion. Phys. Rev. B 25, 4515–4532 (1982).

Das Sarma, S., Adam, S., Hwang, E. H. & Rossi, E. Electronic transport in two-dimensional graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 407–470 (2011).

Wallace, P. R. The band theory of graphite. Phys. Rev. 71, 622–634 (1947).

McCann, E. & Fal’ko, V. Landau-level degeneracy and quantum Hall effect in a graphite bilayer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 086805 (2006).

Martin, J. et al. Observation of electron–hole puddles in graphene using a scanning single-electron transistor. Nature Phys. 4, 144–148 (2008).

Bolotin, K., Sikes, K., Hone, J., Stormer, H. & Kim, P. Temperature-dependent transport in suspended graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 096802 (2008).

Dean, C. R. et al. Boron nitride substrates for high-quality graphene electronics. Nature Nanotech. 5, 722–726 (2010).

Xue, J. M. et al. Scanning tunnelling microscopy and spectroscopy of ultra-flat graphene on hexagonal boron nitride. Nature Mater. 10, 282–285 (2011).

Heersche, H. B., Jarillo-Herrero, P., Oostinga, J. B., Vandersypen, L. M. K. & Morpurgo, A. F. Bipolar supercurrent in graphene. Nature 446, 56–59 (2007).

Du, X., Skachko, I. & Andrei, E. Y. Josephson current and multiple Andreev reflections in graphene SNS junctions. Phys. Rev. B 77, 184507 (2008).

Miao, F. et al. Phase-coherent transport in graphene quantum billiards. Science 317, 1530–1533 (2007).

Popinciuc, M. et al. Zero-bias conductance peak and Josephson effect in graphene-NbTiN junctions. Phys. Rev. B 85, 205404 (2012).

Rickhaus, P., Weiss, M., Marot, L. & Schonenberger, C. Quantum Hall effect in graphene with superconducting electrodes. Nano Lett. 12, 1942–1945 (2012).

Calado, V. E. et al. Ballistic Josephson junctions in edge-contacted graphene. Nature Nanotech. 10, 761–764 (2015).

Ben Shalom, M. et al. Proximity superconductivity in ballistic graphene, from Fabry–Perot oscillations to random Andreev states in magnetic field. Preprint at http://arXiv.org/abs/1504.03286 (2015).

Clayman, B. P. & Frindt, R. F. Superconducting energy gap of NbSe2 . Solid State Commun. 9, 1881–1884 (1971).

Frindt, R. F. Superconductivity in ultrathin NbSe2 layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 28, 299–301 (1972).

Staley, N. E. et al. Electric field effect on superconductivity in atomically thin flakes of NbSe2 . Phys. Rev. B 80, 184505 (2009).

Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013).

Efetov, D. K. Towards Inducing Superconductivity into Graphene PhD thesis, Univ. Columbia (2014).

Ludwig, T. Andreev reflection in bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 75, 195322 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge fruitful discussions with C. Beenakker, I. Aleiner, L. Levitov, A. McDonald, A. Volkov, P. Jarrillo-Herrero, A. Akhmerov, C. Schoenenberger, M. Devoret and J. Pillet. D.K.E. acknowledges the support of the FAME Center, sponsored by SRC MARCO and DARPA. P.K. acknowledge support by DOE (DE-FG02-05ER46215) and C.H. is supported by AFOSR (FA2386-13-1-4122). K.B.E. gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation in the framework of Increase Competitiveness Program of NUST ‘MISiS’ (Nr. K2-2014-015) as well as of Transregio 12 and Priority Program 1459 ‘Graphene’ of Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. K.W. and T.T. acknowledge support from the Elemental Strategy Initiative conducted by the MEXT, Japan. T.T. acknowledges support from a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Grant 262480621 and on Innovative Areas Nano Informatics (Grant 25106006) from JSPS. J.H. acknowledges the NSF DMR-1122594 grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.K.E. and P.K. conceived the experiment. D.K.E. carried out the electrical measurements. D.K.E., L.W. and C.H. fabricated the devices. J.S. and R.C. grew the NbSe2 crystals. T.T. and K.W. grew the hBN crystals. D.K.E. and P.K. performed data analysis. D.K.E. and K.B.E. developed the theoretical model. C.R.D., J.H. and P.K. supervised the experiments. All authors discussed the results and D.K.E. and P.K. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary information (PDF 8184 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Efetov, D., Wang, L., Handschin, C. et al. Specular interband Andreev reflections at van der Waals interfaces between graphene and NbSe2. Nature Phys 12, 328–332 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3583

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3583

This article is cited by

-

Superconducting tunnel junctions with layered superconductors

Quantum Frontiers (2024)

-

Symmetry-broken Josephson junctions and superconducting diodes in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Topotactic fabrication of transition metal dichalcogenide superconducting nanocircuits

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Visualization of edge-modulated charge-density-wave orders in monolayer transition-metal-dichalcogenide metal

Communications Physics (2022)

-

Valence-skipping and quasi-two-dimensionality of superconductivity in a van der Waals insulator

Nature Communications (2022)