Abstract

The search for topological superconductors is a challenging task1,2. One of the most promising directions is to use spin–orbit coupling through which an s-wave superconductor can induce unconventional p-wave pairing in a spin-polarized metal3,4. Recently, synthetic spin–orbit couplings have been realized in cold-atom systems5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 where instead of a proximity effect, s-wave pairing originates from a resonant coupling between s-wave molecules and itinerant atoms17. Here we demonstrate a dynamic process in which spin–orbit coupling coherently produces s-wave Feshbach molecules from a fully polarized Fermi gas, and induces a coherent oscillation between these two. This demonstrates experimentally that spin–orbit coupling does coherently couple singlet and triplet states, and implies that the bound pairs of this system have a triplet p-wave component, which can become a topological superfluid by further cooling to condensation and confinement to one dimension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

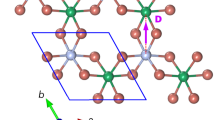

Let us consider two atoms on the positive scattering length (as>0) side of an s-wave Feshbach resonance. In such a system, the Feshbach molecule is in the singlet state  , where |↑〉 and |↓〉 denote two different internal states of atoms. We assume two fermionic atoms are initially prepared in the same spin state (say |↓〉), with different momenta p and q, as represented by blue arrows in Fig. 1. The initial state under anti-symmetrization is given by

, where |↑〉 and |↓〉 denote two different internal states of atoms. We assume two fermionic atoms are initially prepared in the same spin state (say |↓〉), with different momenta p and q, as represented by blue arrows in Fig. 1. The initial state under anti-symmetrization is given by

Now let us turn to a single-particle term that couples two spin states as

where k is momentum and  is the Pauli matrices for atomic spin. If the ‘effective magnetic field’ h is k-independent, it represents the case without spin–orbit coupling. In that case, h acts as a uniform magnetic field and the two atoms with different momenta always rotate in the same way. Therefore, at a given time t, both of them rotate in the same direction

is the Pauli matrices for atomic spin. If the ‘effective magnetic field’ h is k-independent, it represents the case without spin–orbit coupling. In that case, h acts as a uniform magnetic field and the two atoms with different momenta always rotate in the same way. Therefore, at a given time t, both of them rotate in the same direction  , as shown in Fig. 1a. The final state wavefunction is then given by

, as shown in Fig. 1a. The final state wavefunction is then given by

As this state remains in the triplet channel, 〈S|Ψ〉fis always zero. Thus, there cannot be any coherent transition to the Feshbach molecular state. On the other hand, if any component of h depends on k, it means that the spin and momentum are coupled. In this case, the amount of rotation each spin executes depends on its momentum and is in general different for different momentum. Suppose at time t, an atom with momentum p rotates to  and an atom with momentum q rotates to

and an atom with momentum q rotates to  , as shown in Fig. 1b, the final-state wavefunction can now be written as

, as shown in Fig. 1b, the final-state wavefunction can now be written as

It is straightforward to show that the wavefunction equation (2) can be rewritten as

where  and

and  are the triplet and singlet components, respectively. Thus, 〈S|Ψ〉f is non-zero and these two atoms can experience an s-wave resonant interaction. Therefore, a transition to the Feshbach molecular state can be induced.

are the triplet and singlet components, respectively. Thus, 〈S|Ψ〉f is non-zero and these two atoms can experience an s-wave resonant interaction. Therefore, a transition to the Feshbach molecular state can be induced.

The left and right columns represent spins of two atoms with different momenta. a,b represent two cases in the absence (a) or in the presence (b) of spin–orbit coupling. a, h(p) = h(q). b,  when

when  . The red arrows represent the spin direction at t = 0 and the yellow arrows represent the spin direction at finite time t.

. The red arrows represent the spin direction at t = 0 and the yellow arrows represent the spin direction at finite time t.

Nevertheless, in practice, it is known that a momentum-independent coupling, such as radiofrequency coupling, can also produce Feshbach molecules in a degenerate Fermi gas. In such a process, the atoms in |↓〉 first evolve to the superposition of |↑〉 and |↓〉 through radiofrequency coupling. Then, after decoherence, it becomes an incoherent mixture of scattering atoms in |↑〉 and |↓〉, and further, the inelastic collision can convert some atoms in the mixture into molecules18. It is important to note that a decoherence process has to be involved in such a process. In contrast, the spin–orbit-coupling-induced transition discussed above does not require any incoherent process, and is a fully quantum coherent process.

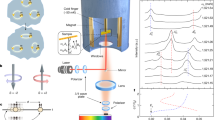

In our experiment, we generate coupling between |9/2,−9/2〉 (denoted by |↓〉) to |9/2,−7/2〉 (denoted by |↑〉) of 40K gas using two Raman beams with relative angle θ (refs 13, 15; Methods), whose Hamiltonian is given by5

where 2k0≡2krsin(θ/2) is the momentum transfer (kr is the single-photon recoil momentum), Ω is the strength of the Raman coupling and δ is two-photon detuning. Here, kx denotes the quasi-momentum of atoms, which relates to the real momentum as  with

with  for spin-up and -down, respectively. On comparison with equation (1), it is clear that h = (Ω/2,0,−δ/2−kxk0/m). If the two Raman beams are parallel to each other, we have θ = 0 and thus k0 = 0. In this case, there is no spin–orbit coupling. When

for spin-up and -down, respectively. On comparison with equation (1), it is clear that h = (Ω/2,0,−δ/2−kxk0/m). If the two Raman beams are parallel to each other, we have θ = 0 and thus k0 = 0. In this case, there is no spin–orbit coupling. When  , k0 becomes non-zero and there will be a spin–orbit coupling effect. According to the above analysis, a fully polarized Fermi gas cannot be coupled to the Feshbach molecular state if the two Raman beams are parallel, whereas coherent molecule production is allowed if they are not parallel (see Supplementary Information for more discussion).

, k0 becomes non-zero and there will be a spin–orbit coupling effect. According to the above analysis, a fully polarized Fermi gas cannot be coupled to the Feshbach molecular state if the two Raman beams are parallel, whereas coherent molecule production is allowed if they are not parallel (see Supplementary Information for more discussion).

Our experiment is performed at 201.4 G, below the Feshbach resonance between |9/2,−9/2〉 and |9/2,−7/2〉 located at 202.2 G, which corresponds to a binding energy of Eb = h×30 kHz (corresponding to 3.59Er) for the Feshbach molecules and 1/(kFas)≈0.92 for our typical density, where as is the s-wave scattering length and kF is the Fermi wavevector. After applying the Raman lasers for a certain pulse duration, we turn off the Raman lasers and measure the population of Feshbach molecules and atoms in the |9/2,−7/2〉 state with a radiofrequency pulse. This radiofrequency field drives a transition from |9/2,−7/2〉 to |9/2,−5/2〉. For a mixture of |9/2,−7/2〉 and Feshbach molecules, as a function of radiofrequency frequency νRF, we find two peaks in the population of |9/2,−5/2〉, as shown in Fig. 2b. The first peak (blue curve) is attributed to free atom–atom transition and the second peak (red curve) is attributed to molecule–atom transition. Thus, in the following, we set νRF to 47.14 MHz to measure Feshbach molecules.

a, Schematic of the energy levels. A pair of Raman lasers couples the spin-polarized state |9/2,−9/2〉 to the Feshbach molecules in the Fermi gas 40K. The populations of Feshbach molecules and atoms in the |9/2,−7/2〉 state are measured by driving a radiofrequency pulse to |9/2,−5/2〉. Inset, plot of the experimental geometry. b, Radiofrequency spectrum |9/2,−7/2〉 to |9/2,−5/2〉 transition applied to a mixture of Feshbach molecules and scattering atoms in |9/2,−7/2〉. c–e, The population of Feshbach molecules detected by the radiofrequency pulse as a function of pulse duration of the Raman pulse. c–e, The angle of the two Raman beams is θ = 180° (c), θ = 90° (d) and θ = 0° (e). The Raman coupling strength is Ω = 1.3Er and the two-photon Raman detuning is δ = −Eb = −3.59Er. The error bars in c and d represent the standard deviation of repeated measurements.

When the two-photon Raman detuning δ is set to δ = −Eb = −3.59Er, as shown in Fig. 2a, we measure the population of Feshbach molecule as a function of pulse duration for three different angles, θ = 180°, θ = 90° and θ = 0°, as shown in Fig. 2c–e. We find for θ = 180°, Feshbach molecules are created by a Raman process and the coherent Rabi oscillation between atom–molecule can be seen clearly. For θ = 90°, production of Feshbach molecules is reduced a little bit and the atom–molecule Rabi oscillation becomes invisible. For θ = 0°, no Feshbach molecule is created even up to 40 ms, which means the transition between Feshbach molecules and a fully polarized state is prohibited if the Raman process has no momentum transfer. In addition, as reported in ref. 16, we also see heating and atom loss due to the Raman laser. When t∼30 ms, the temperature is increased to around 1TF (TF is the Fermi temperature) and atoms are lost to 2/3 of initial numbers.

Figure 3 shows the population of Feshbach molecules detected by the radiofrequency pulse as a function of two-photon detuning δ with the fixed Raman coupling strength Ω = 1.3Er and the pulse duration 15 ms. For θ = 180° and θ = 90° we find that the formation of Feshbach molecules starts to occur when δ≳−7.18Er, reaches a maximum around δ≈−2.39Er (it is a little bit larger than −Eb = −3.59Er, which is probably due to the momentum recoil from the Raman beams), and gradually decreases to zero around δ = +3.59Er, as shown by red data points in Fig. 3a,b. (See Supplementary Information for a comparison with Fermi’s golden rule calculation.) In contrast, for θ = 0°, we find no Feshbach molecule production until δ≳−1.79Er and the Feshbach molecules populate only within a narrow window around δ = 0, as shown in Fig. 3c. The peak value in Fig. 3c is also much reduced compared with Fig. 3a and 3b.

The Raman coupling strength is Ω = 1.3Er and the duration of the Raman pulse is 15 ms. a–c, The angle of two Raman beams is θ = 180° (a), θ = 90° (b) and θ = 0° (c), respectively. The red data points are Feshbach molecular population and the black data points are population of scattering atoms in the |9/2,−7/2〉 state. The error bars represent the standard deviation of repeated measurements.

The atom–molecule transition shown in Fig. 3 contains both the spin–orbit-coupling-induced coherent process and the incoherent process discussed above. For the incoherent process, sufficient population of scattering atoms in |9/2,−7/2〉 is inevitable. In contrast, the coherent process can still exist even when the population of the scattering atoms in |9/2,−7/2〉 is negligible at sufficiently large detuning. Thus, to further distinguish these two processes, we measure the population of scattering atoms in the |9/2,−7/2〉 state for three cases with θ = 180° (Fig. 3a), 90° (Fig. 3b), 0° (Fig. 3c), after a Raman pulse with the same intensity and the same duration. Comparing the populations of scattering atoms in the state |9/2,−7/2〉 and Feshbach molecules in Fig. 3, we find that for θ = 180° and θ = 90°, significant molecule population exists in the frequency regime δ≲−3.59Er where no atoms in |9/2,−7/2〉 are found. This confirms the coherent nature of Feshbach molecular production. On the other hand, for θ = 0°, no Feshbach molecules can be found if atoms in |9/2,−7/2〉 do not exist (either δ≲−2.39Er or δ≳+2.39Er). This shows that scattering atoms in the state |9/2,−7/2〉 is prerequisite for incoherent molecular formation18.

More direct evidence for the coherent nature of molecular production is the Rabi oscillation between the Feshbach molecular state and a fully polarized Fermi gas. Previously coherent atom–molecule oscillation has been observed only in bosonic atomic gas19 and boson–fermion mixtures20. In a Fermi gas, the energy of atoms in scattering states spreads over a wide energy range of the order of Fermi energy (2.2Er in our system), which inevitably leads to damping of the Rabi oscillation. (See Supplementary Information for a two-body calculation for illustration purposes.) However, by tuning the laser intensity and, as a result, the magnitude of the Rabi frequency, the oscillation period can be made shorter compared with the damping time and can be readily observed in the experiment. In Fig. 4 we plot the Feshbach molecular fraction as a function of the pulse duration of the Raman laser with two-photon detuning tuned to molecule binding energy. In Fig. 4a–c at least one oscillation period can be identified. In contrast, in Fig. 4d, with a smaller Raman intensity, the oscillation becomes invisible. For Fig. 4a–c we take the first minimum as one period τ, and plot the Rabi oscillation frequency ν = 1/τ as a function of Raman coupling Ω in Fig. 4e), and find a perfect linear relation. This is indicative of a coherent process in which the oscillation frequency is proportional to the Raman-coupling strength. Finally in Fig. 4f we plot the Feshbach molecular fraction for various temperatures. We find that when the initial temperature increases from T/TF = 0.3 to T/TF = 0.68, the oscillation period is almost unchanged but the oscillation itself becomes less and less visible. This shows the increase of damping rate with the increase of temperature.

a–d, Population of Feshbach molecules as a function of pulse duration of Raman laser. The angle of the two Raman beams is θ = 180° and the two-photon detuning is set as δ = −Eb = −3.59Er. For a–d, temperature T/TF = 0.3, and the Raman coupling strength is Ω = 2.8Er (a), Ω = 1.95Er (b), Ω = 1.3Er (c) and Ω = 0.65Er (d). e, For T/TF = 0.3, the Rabi frequencies obtained from a–c as a function of the Raman coupling strength. f, Feshbach molecular fractions as a function of pulse time for different temperatures. The Raman coupling strength Ω = 1.3Er. Initial T/TF = 0.3 for red curve, T/TF = 0.48 for blue curve, and T/TF = 0.68 for green curve. The error bars represent the standard deviation of repeated measurements.

Finally, we study the creation of Feshbach molecules for different magnetic fields corresponding to different binding energies Eb of the molecules. The detuning δ is chosen to be δ = −Eb. Here, the Feshbach molecules are dissociated by a magnetic sweep over the Feshbach resonance instead of the radiofrequency pulse. As shown in Fig. 5, we find that the Feshbach molecular population increases at the higher magnetic field. This is because the atom–molecule transition amplitude depends on the overlap between the wavefunction of the Feshbach molecule and that of two free atoms (that is, the Franck–Condon factor), which increases as the absolute value of Eb decreases.

The Raman coupling strength is Ω = 1.3Er and the duration of the pulse is 7 ms. The angle of the two Raman beams is θ = 180°. The detuning is chosen such that δ = −Eb for each magnetic field. a, The Feshbach molecular binding energy as a function of magnetic field. The inset in a shows the experimental sequence. TOF, time of flight. b, Fraction of Feshbach molecules produced after the Raman pulse. The Feshbach molecules are dissociated by a magnetic ramp over the Feshbach resonance. The error bars represent the standard deviation of repeated measurements.

Our work is also connected to a previous atomic clock experiment, where a laser beam is applied to couple ground and electronic excited states of an alkali-earth atom21. The coupling will also be accomplished by momentum transfer, resulting in it being a similar type of spin–orbit coupling as the one discussed here. In their case (no Feshbach resonance physics involved), the interaction shift and the suppression of the interaction shift have been found21,22 to be due to the singlet–triplet coupling.

The coherent dynamics demonstrated here shows that the bound state of this system contains both singlet and triplet components. Owing to antisymmetrization of the fermion wavefunction, the triplet component should at least be a p-wave pairing. In contrast, p-wave Feshbach molecules directly created by a p-wave resonance23,24,25 suffer from strong collision loss24,26. Although the temperature of our present system is still above the condensation temperature of these pairs, one may still expect some interesting physics of these non-condensed non-trivial pairs. At low temperature and lower dimension, these pairs will exhibit topological superfluidity.

Methods

Experimental set-up.

This experiment starts with a degenerate Fermi gas of about 2×10640K in the |9/2,9/2〉 state, which has been evaporatively cooled to T/TF≈0.3 with bosonic 87Rb atoms in the |2,2〉 inside the crossed optical trap13,27,28,29, where TF is the Fermi temperature defined by  , and the geometric mean of trapping frequencies

, and the geometric mean of trapping frequencies  in our system, and N is the number of fermions. A 780 nm laser pulse is applied for 0.03 ms to remove the 87Rb atoms in the mixture without heating the 40K atoms. Subsequently, the fermionic atoms are transferred into the lowest state |9/2,−9/2〉 through a rapid adiabatic passage induced by a radiofrequency field of 80 ms at 4 G. A homogeneous bias magnetic field for magnetic Feshbach resonance along the z axis (gravity direction) is produced by the quadrupole coils (operating in the Helmholtz configuration).

in our system, and N is the number of fermions. A 780 nm laser pulse is applied for 0.03 ms to remove the 87Rb atoms in the mixture without heating the 40K atoms. Subsequently, the fermionic atoms are transferred into the lowest state |9/2,−9/2〉 through a rapid adiabatic passage induced by a radiofrequency field of 80 ms at 4 G. A homogeneous bias magnetic field for magnetic Feshbach resonance along the z axis (gravity direction) is produced by the quadrupole coils (operating in the Helmholtz configuration).

Raman coupling.

A pair of 772.4 nm Raman lasers is extracted from a continuous-wave Ti–sapphire single-frequency laser. Two Raman beams are frequency-shifted around −77 MHz and −122 MHz by two single-pass acousto-optic modulators, respectively, to precisely control their frequency difference. These two Raman beams have a maximum intensity I = 130 mW for each beam, and they overlap in the atomic cloud with 1/e2 radii of 200 μm. The Raman lasers are applied to spin-polarized 40K gas in the |F,mF〉 = |9/2,−9/2〉 state with relative wavevector along  . The two Raman beams correspond to π and σ polarization along the quantization axis

. The two Raman beams correspond to π and σ polarization along the quantization axis  , respectively. Thus, the Raman process couples |9/2,−9/2〉 (denoted by |↓〉) to |9/2,−7/2〉 (denoted by |↑〉), and the momentum transfer in the Raman process is 2k0≡2krsin(θ/2), where kr = 2πℏ/λ is the single-photon recoil momentum, λ is the wavelength of the Raman beam, and θ is the angle between two the Raman beams. The recoil energy Er = kr2/2m = h×8.36 kHz. The relative frequency between the two lasers ω1−ω2 can be precisely controlled, and the two-photon detuning δ≡ℏ(ω1−ω2)−ℏωZ, where ℏωZ is the Zeeman splitting between |↑〉 and |↓〉. In addition, we should be careful that each single beam ω1 and ω2 will not cause a bound-to-bound transition30.

, respectively. Thus, the Raman process couples |9/2,−9/2〉 (denoted by |↓〉) to |9/2,−7/2〉 (denoted by |↑〉), and the momentum transfer in the Raman process is 2k0≡2krsin(θ/2), where kr = 2πℏ/λ is the single-photon recoil momentum, λ is the wavelength of the Raman beam, and θ is the angle between two the Raman beams. The recoil energy Er = kr2/2m = h×8.36 kHz. The relative frequency between the two lasers ω1−ω2 can be precisely controlled, and the two-photon detuning δ≡ℏ(ω1−ω2)−ℏωZ, where ℏωZ is the Zeeman splitting between |↑〉 and |↓〉. In addition, we should be careful that each single beam ω1 and ω2 will not cause a bound-to-bound transition30.

Detecting molecules.

To detect molecules, after the radiofrequency pulse, we abruptly turn off the optical trap and the magnetic field, and let the atoms ballistically expand for 12 ms in the presence of a magnetic field gradient applied along  , and finally take an absorption image along

, and finally take an absorption image along  to measure the population of the |9/2,−5/2〉 state.

to measure the population of the |9/2,−5/2〉 state.

Population of atoms in the |9/2,−7/2〉 state.

We find in all three cases in Fig. 3, the population of atoms in |9/2,−7/2〉 becomes non-zero for δ≳−3.59Er as shown by the black data points in Fig. 3. The difference between Fig. 3a–c is that for Fig. 3a,b, the system mainly populates in |9/2,−7/2〉 when δ>3.59Er, whereas for Fig. 3c the population of |9/2,−7/2〉 vanishes when δ>2.39Er. This is because for the case without spin–orbit coupling (Fig. 3c), the resonance always takes place when two-photon detuning matches the Zeeman energy, that is, δ = 0, for atoms in all momenta. In contrast, for Fig. 3a,b with spin–orbit coupling, the resonance frequency is momentum dependent and spread over a much wider frequency range13,14,31,32.

References

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Qi, X-L. & Zhang, S-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Superconducting proximity effect and Majorana fermions at the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096407 (2008).

Sau, J. D., Lutchyn, R. M., Tewari, S. & Das Sarma, S. Generic new platform for topological quantum computation using semiconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 040502 (2010).

Lin, Y-J., Jiménez-García, K. & Spielman, I. B. Spin–orbit-coupled Bose–Einstein condensates. Nature 471, 83–86 (2011).

Fu, Z., Wang, P., Chai, S., Huang, L. & Zhang, J. Bose–Einstein condensate in a light-induced vector gauge potential using the 1064 nm optical dipole trap lasers. Phys. Rev. A 84, 043609 (2011).

Williams, R. A. et al. Synthetic partial waves in ultracold atomic collisions. Science 335, 314–317 (2012).

Zhang, J-Y. et al. Collective dipole oscillation of a spin–orbit coupled Bose–Einstein condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 115301 (2012).

Zhang, L. et al. Stability of excited dressed states with spin–orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 87, 011601(R) (2013).

Zhang, J-Y. et al. Experimental determination of the finite-temperature phase diagram of a spin–orbit coupled Bose gas. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1305.7054 (2013).

Qu, C., Hamner, C., Gong, M., Zhang, C. & Engels, P. Non-equilibrium spin dynamics and Zitterbewegung in quenched spin–orbit coupled Bose–Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 88, 021604(R) (2013).

LeBlanc, L. J. et al. Direct observation of Zitterbewegung in a Bose–Einstein condensate. New J. Phys. 15, 073011 (2013).

Wang, P. et al. Spin–orbit coupled degenerate Fermi gases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 095301 (2012).

Cheuk, L. W. et al. Spin–injection spectroscopy of a spin–orbit coupled Fermi gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 095302 (2012).

Fu, Z. et al. Radio-frequency spectroscopy of a strongly interacting spin–orbit-coupled Fermi gases. Phys. Rev. A 87, 053619 (2013).

Williams, R. A., Beeler, M. C., LeBlanc, L. J., Jimenez-Garcia, K. & Spielman, I. B. A Raman-induced Feshbach resonance in an effectively single-component Fermi gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 095301 (2013).

Chin, C., Grimm, R., Julienne, P. & Tiesinga, E. Feshbach resonances in ultracold gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1225–1286 (2010).

Jochim, S. et al. Pure gas of optically trapped molecules created from fermionic atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 240402 (2003).

Donley, E. A., Claussen, N. R., Thompson, S. T. & Wieman, C. E. Atom–molecule coherence in a Bose–Einstein condensate. Nature 417, 529–533 (2002).

Olsen, M. L., Perreault, J. D., Cumby, T. D. & Jin, D. S. Coherent atom–molecule oscillations in a Bose–Fermi mixture. Phys. Rev. A 80, 030701(R) (2009).

Campbell, G. K. et al. Probing interactions between ultracold fermions. Science 324, 360–363 (2009).

Swallows, M. D. et al. Suppression of collisional shifts in a strongly interacting lattice clock. Science 331, 1043–1046 (2011).

Regal, C. A., Ticknor, C., Bohn, J. L. & Jin, D. S. Tuning p-wave interactions in an ultracold Fermi gas of atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 053201 (2003).

Zhang, J. et al. P-wave Feshbach resonances of ultracold 6Li. Phys. Rev. A 70, 030702 (2004).

Schunck, C. H. et al. Feshbach resonances in fermionic 6Li. Phys. Rev. A 71, 045601 (2005).

Gaebler, J. P., Stewart, J. T., Bohn, J. L. & Jin, D. S. p-wave Feshbach molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 200403 (2007).

Xiong, D. et al. Quantum degenerate Fermi–Bose mixtures of 40K and 87Rb atoms in a quadrupole-Ioffe configuration trap. Chin. Phys. Lett. 25, 843–846 (2008).

Xiong, D., Wang, P., Fu, Z. & Zhang, J. Transport of Bose–Einstein condensate in QUIC trap and separation of trapping spin states. Opt. Express 18, 1649–1656 (2010).

Xiong, D., Wang, P., Fu, Z., Chai, S. & Zhang, J. Evaporative cooling of 87Rb atoms into Bose–Einstein condensate in an optical dipole trap. Chin. Opt. Lett. 8, 627–629 (2010).

Fu, Z. et al. Optical control of a magnetic Feshbach resonance in ultracold Fermi gases. Phys. Rev. A 88, 041601 (2013).

Wang, P., Fu, Z., Huang, L. & Zhang, J. Momentum-resolved Raman spectroscopy of a noninteracting ultracold Fermi gas. Phys. Rev. A 85, 053626 (2012).

Fu, Z., Wang, P., Huang, L., Meng, Z. & Zhang, J. Momentum-resolved Raman spectroscopy of bound molecules in ultracold Fermi gas. Phys. Rev. A 86, 033607 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank C. Chin for helpful discussions. This research is supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (Grant No. 2011CB921601, No. 2011CB921500 and No. 2012CB922104), NSFC (Grant No. 11234008, No. 11004118, No. 11174176 and No. 11222430) and NSFC Project for Excellent Research Team (Grant No. 61121064). P.Z. is supported by the NCET Program. H.Z. is supported by Tsinghua University Initiative Scientific Research Program, S.Z. is supported by the start-up fund from the University of Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. and P.W. built the experimental set-up. J.Z., P.Z. and H.Z. conceived and designed the experiments. Z.F., L.H., Z.M., P.W. and J.Z. carried out the experiment. P.Z., H.Z., S-Z.Z., J.Z. and L.Z. contributed with theoretical calculation and analysis. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and J.Z., H.Z., P.Z., P.W. and S-Z.Z. participated in writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information (PDF 543 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, Z., Huang, L., Meng, Z. et al. Production of Feshbach molecules induced by spin–orbit coupling in Fermi gases. Nature Phys 10, 110–115 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2824

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2824

This article is cited by

-

Spin-orbital-angular-momentum-coupled quantum gases

AAPPS Bulletin (2022)

-

Ground-State Properties of Rotating Binary Spin–Orbit-Coupled Bose Gas with Mass Imbalance

Journal of Low Temperature Physics (2021)

-

Magnetically tunable atom-exchange process involving ultracold weakly bound Feshbach molecules

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2020)

-

Creating Spin-One Fermions in the Presence of Artificial Spin–Orbit Fields: Emergent Spinor Physics and Spectroscopic Properties

Journal of Low Temperature Physics (2018)

-

Striking stripes

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2017)