Abstract

Liquid water at atmospheric pressure can be supercooled to −41 °C (ref. 1) and superheated to +302 °C (ref. 2). Experiments involving fluid inclusions of water in quartz suggest that water is capable of sustaining pressures as low as −140 MPa before it breaks by cavitation3. Other techniques, for which cavitation occurs consistently at around −30 MPa (ref. 4), produce results that cast doubt on this claim. Here we reproduce the fluid-inclusion experiment, performing repeated measurements on a single sample—a method used in meteorology5, bioprotection6 and protein crystallization7, but not yet in liquid water under large mechanical tension. The resulting cavitation statistics are characteristic of a thermally activated process, and both the free energy and the volume of the critical bubble are well described by classical nucleation theory when the surface tension is reduced by less than 10%, consistent with homogeneous cavitation. The line of density maxima of water at negative pressure is found to reach 922.8 kg m−3 at around 300 K, which further constrains its contested phase diagram.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Owing to the strong cohesion of water, which manifests in its large surface tension, the liquid is expected to withstand pressures in excess of −100 MPa (ref. 8), as predicted for instance by classical nucleation theory9 (CNT). The only experimental technique for which such large tensions have been reported uses water inclusions in quartz3. The magnitude of the tension was also independently confirmed by light scattering10. Several other independent experimental techniques report cavitation at much lower tensions4, prompting the proposal of a new kind of heterogeneous cavitation involving stabilization of water in an inclusion against nucleation by impurities11 or surfaces12. Agreement between cavitation-pressure measurements and CNT would thus be advantageous.

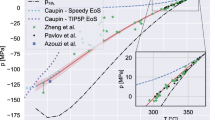

In the work that pioneered the fluid-inclusions technique3, a large number of inclusions, covering a wide density range, were studied. However, the cavitation event in each individual inclusion was usually observed only once. One inclusion was observed in repeated runs “to nucleate randomly in the range 40–47 °C and occasionally not at all”3, which was qualitatively interpreted as evidence for the crossing of the line of density maxima (LDM) of water. In the present work, we chose to focus on only one inclusion, and to perform a large number of cavitation experiments to obtain the statistics of nucleation. We confirm the previous data in terms of cavitation threshold, but in addition, by probing nucleation rates over three decades and using the nucleation theorem13, we gain insight into the nanoscopic mechanism underlying bubble nucleation. The results are consistent with CNT with a slightly reduced surface tension, related to the small size of the critical bubble. Moreover, the analysis allows us to derive quantitative information on the LDM, which is of paramount importance in the debate about the origin of water anomalies. Indeed, if the LDM sustains a negative slope (Fig. 1), it will intersect the liquid–vapour spinodal and bend it to lower tension at lower temperature14; whereas if the LDM changes slope, bending to lower temperature at higher tension, the spinodal remains monotonic15. Up to now, the LDM had been measured only down to −20.3 MPa at 280.84 K as shown in Fig. 1 (ref. 16). Our result supports a negatively sloped LDM much further in the metastable region.

Equilibrium transitions are given by blue curves. The extrapolation of the EOS measured at positive pressure21 is used to plot the liquid–vapour spinodal (red), the LDM (black) and the isochore at ρ = 922.8 kg m−3 (green) corresponding to the inclusion studied (see Methods for details). Here the spinodal is re-entrant14, but other scenarios suggest that it remains monotonic9,15. The LDM has been measured only down to −20.3 MPa at 280.84 K (ref. 16; black circles). The inclusion studied here (volume V = 570 μm3) is shown as an inset, with a bubble in the top left corner. The thick green section shows the series of 154 Tcav values measured in the present study; they correspond to a cavitation pressure Pcav around −120 MPa.

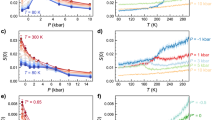

Tension in a single inclusion was generated by isochoric cooling (see Fig. 1 and Methods) at a constant rate, with three values of the cooling rate r. A total of 154 values of the cavitation temperature Tcav were measured and sorted (see Methods) to generate the survival curves Σ(T) (probability that nucleation did not occur during cooling down to T) shown in Fig. 2. We find that the faster the cooling rate, the higher Σ at a given T. This feature and the shape of the survival curves can be explained as follows. The probability of nucleation is described by a thermally activated process that occurs at a rate Γ = Γ0exp(−Eb/(kBT)), where Γ0 is a kinetic prefactor (see Methods) and Eb is the free-energy barrier that has to be overcome. Integration from the temperature Th at which the cooling starts (Fig. 1, point b) yields (see Supplementary Information):

As Eb/(kBT) appears in an exponential, we can safely replace Th by infinity, and Γ0(T′) by its value at a reference temperature. Equation (1) explains why Σ increases with r. Moreover, it predicts a data collapse when plotting −rlnΣ versus T: this is borne out by the experiment (Fig. 2, inset). The small data spread is due to statistical fluctuations, as we have checked by simulations (see Supplementary Information). This proves that all data are consistently described by the same function for Eb over more than three decades of nucleation rates. For a quantitative analysis, we use a second-order temperature expansion of Eb/(kBT) (equation (2), Methods). A first-order expansion would give a straight line in Fig. 2, inset. As the data exhibit a curvature, the experiment is able to capture the second-order term in the expansion. Including this term and integrating equation (1) yields an equation for −rlnΣ involving the error function and three adjustable parameters (equation (3), Methods), which was used to fit the collapsed data for ln(−rlnΣ) simultaneously (Fig. 2, inset). The main plot in Fig. 2 also shows that the global fit parameters give Σ in good agreement with each data set taken separately. Uncertainties on the parameters were calculated using simulations of the whole experimental procedure (see Supplementary Information).

Three cooling rates were investigated: r = 2 (purple squares), 5 (green crosses) and 10 K min−1 (red circles). The data can be collapsed together (inset) by plotting the quantity −rlnΣ/ln2. The solid black curve in the inset is a fit based on a quadratic expansion of Eb/(kBT) (see Methods). The fit parameters are given in Supplementary Table S1. The calculated Σ for each r based on these values (main graph, solid curves) is in good agreement with each separate data set.

This statistical measurement contains a wealth of physical information. Figure 3 compares the experimental result for Eb with CNT (ref. 9). In CNT, the free-energy barrier Eb is reached for a critical bubble that is a sphere of radius Rc with an infinitely thin boundary. Using the tabulated surface tension σ (ref. 17), we find Eb larger than the experimental values. One possible explanation for this discrepancy involves heterogeneous nucleation on the walls of the inclusion: a finite contact angle θc of the liquid/vapour interface on the substrate would reduce Eb by a geometrical factor9. However, this factor varies slowly with θc, and the observed reduction would require θc≃60°, whereas water wets silica perfectly (θc = 0°). Although an impurity inducing a large θc cannot be totally excluded, we note that the “dramatic character” of the cavitation process observed in a previous study18 was invoked as an argument in favour of homogeneous nucleation in smooth-walled inclusions such as the one studied here. The reduction of Eb is more likely due to the simplifying approximations involved in CNT: with Rc being in the nanometre range, the surface tension for such a small bubble and curved interface might differ from the bulk one; and the liquid/vapour interface thickness, which is also around 1 nm (ref. 8), cannot be neglected. In general, these effects lead to a lower free-energy barrier. In fact, a small relative decrease in σ, between 7.4 and 9% across the experimental temperature range, is sufficient to bring CNT in agreement with the experiment. Such a modification is usually ascribed to the Tolman length δ (ref. 19), which is a microscopic length that accounts for the change in surface tension with the radius of curvature R of the interface:

For simplicity we assume a constant δ. Remarkably, this is sufficient to obtain a good fit (Fig. 3), choosing δ = −0.047 nm (see Supplementary Information). This is plausible, being negative and less than the size of a water molecule (0.3 nm), similar to results obtained from simulations of the Lennard-Jones fluid20. An alternative view regarding the origin of the correction to CNT is given by density functional theory. Instead of a sharp liquid/vapour interface, it considers smoothly varying profiles and has the spinodal curve built in. For cavitation in water, this gives a correction at 330 K equivalent to a decrease in surface tension by 13 and 23.8% for two choices for the equation of state8 (EOS), close to the present value.

CNT predictions (dash–dotted green curves) without (top, thin) and with (bottom, thick) a Tolman length δ = −0.047 nm compared with the experimental result (equation (2), Methods, with parameters from Supplementary Table S1, solid red curve). The red dotted curves show the effect of changing all fitted parameters by plus or minus their error bars. Eb/(kBT) reaches a minimum at Tmin (red arrow).

From the curvature in Eb/(kBT), we deduce that it reaches a minimum at Tmin = 321.4±4.3 K (red arrow in Fig. 3), very close to the minimum Tcav in the experiment, 322.35 K, which gives us confidence in the short extrapolation involved. At Tmin, the nucleation rate reaches a maximum, and so does the metastability. This is related to the shape of the isochore (Fig. 1), as already proposed in ref. 3: when it intersects the LDM of water at TLDM, the system reaches a maximum tension. The extrapolation of the EOS measured at positive pressure21 gives TLDM = 296.4 K. With this EOS and after accounting for the temperature variation of σ3/T (see Supplementary Information), CNT predicts Tmin = 317.6 K. The agreement with the experimental Tmin is remarkable, because the analysis of the experimental data to find Tmin does not rely on any specific EOS. We thus find support for the extrapolation of the EOS measured at positive pressure21, which gives a negative slope in the P–T plane for the LDM, far inside the negative pressure region. We emphasize that the previous measurement of the LDM (ref. 16) reached a maximum tension of −20.3 MPa. Even if we add only one point, it lies at a much larger tension, around −120 MPa, a region highly relevant in the debate about the scenarios proposed to explain water anomalies. Our result stands in contrast with some of the simulation results: for instance, for the ST2 potential15, the LDM reaches a maximum temperature at P = −25 MPa, and exhibits a positive slope at larger tension. We conclude that either the LDM is monotonic and the spinodal is re-entrant, or the turning point of the LDM lies at a density lower than 922.8 kg m−3.

The results for Eb/(kBT) can also be analysed using the nucleation theorem13. Without assuming any specific microscopic model for nucleation, it relates the properties of the critical nucleus to the variation of the free-energy barrier. In the present case of an isochoric experiment, it directly provides a lower bound on −ΔV c (see Supplementary Information), where ΔV c<0 is the excess volume of the critical nucleus. Using an analogy with CNT, we estimate that −ΔV c is around twice this lower bound (see Supplementary Information). The results are shown in Fig. 4. The small difference between the data and the corrected CNT for Eb/(kBT) (Fig. 3) is amplified by taking the derivative, but the agreement remains satisfactory. For comparison, in the acoustic cavitation experiment11 at the same temperature, the cavitation pressure was around five times less negative but −ΔV c was only slightly higher, around 10 nm3: this suggests that acoustic cavitation occurs heterogeneously on a ubiquitous impurity11, which helps to keep a small critical nucleus with a free-energy barrier that can be overcome by thermal fluctuations. The nature of this ubiquitous impurity remains an outstanding question and calls for more experiments and simulations.

Methods

The quartz sample was synthesized in a previous study22 following the thermal crack sealing method23 using an internally heated apparatus at 750 MPa and 530 °C for 13 days. The inclusion studied was chosen for its extreme metastability, around −120 MPa, close to the largest tension obtained previously with a higher density inclusion3. It is a 20-μm-long and 4-μm-wide tube, with a volume of 570 μm3 (Fig. 1). Among the samples available to us22, those with lower densities nucleate at higher temperatures and lower tensions, and samples with higher densities nucleate very rarely, which precludes the statistical approach. A previous statistical study on the lifetime of the metastable state in one inclusion has been reported24, but the largest tension reached was −16.7 MPa and only a limited analysis was performed.

The quartz fragment was placed on a heating–cooling stage (Linkam THMS 600) mounted on a microscope (Olympus BHS). Phase changes in the inclusions were observed with a ×50 long-working-distance objective (Olympus). The temperature cycles of the stage are controlled using a computer program. Phase changes are recorded using a black and white camera with a complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor 2/3 inch sensor, 1280×1024 pixels2 (Marlin) at a rate of 13 fps. The generation of negative pressure can be understood from Fig. 1. We start with a bi-phasic fluid inclusion, containing liquid and vapour (a in Fig. 1). On warming along the liquid–vapour equilibrium (a–b), the bubble disappears at the homogenization temperature Th(b), from which the liquid density ρ is obtained using the known EOS (ref. 21). For the inclusion studied, Th = 143.7 °C and ρ = 922.8 kg m−3. Then, on isochoric cooling, the bubble does not reappear and the liquid is stretched (b–c), until cavitation occurs at Tcav (c), bringing the system back to equilibrium (a).

We have studied a single inclusion with ramp-like cooling cycles: the temperature decreases linearly with time. We used three cooling rates, r = 2, 5 and 10 K min−1, measuring 61, 33 and 60 values of Tcav, respectively. For a given r, the Nr values of Tcav were sorted in ascending order to give a list . The survival probability was deduced as Σ(Ti) = (i−1/2)/Nr.

The nucleation rate is Γ = Γ0exp[−Eb/(kBT)], where Γ0 is a prefactor and Eb is the free-energy barrier that has to be overcome. We take  (refs 9, 25), where NA is Avogadro’s constant, m is the mass of one molecule and σ is the surface tension of water. There is some uncertainty in the value of the prefactor Γ0, but, because of the exponential in the rate, changes by several orders of magnitude affect the results only marginally. In the present experiment, the rate Γ ranges from 2.5×1011 to 3×1014 m−3 s−1.

(refs 9, 25), where NA is Avogadro’s constant, m is the mass of one molecule and σ is the surface tension of water. There is some uncertainty in the value of the prefactor Γ0, but, because of the exponential in the rate, changes by several orders of magnitude affect the results only marginally. In the present experiment, the rate Γ ranges from 2.5×1011 to 3×1014 m−3 s−1.

The free-energy barrier to nucleation is calculated from equation (1) (see Supplementary Information for details). We use a second-order temperature expansion:

where ξ and κ are non-dimensional parameters, and T* = 328 K is a reference temperature in the middle of the experimental range of Tcav. The choice of T* does not affect the conclusions of the study. Equation (1) becomes:

where erf stands for the error function. Equation (3) was used to fit the data for ln(−rlnΣ) (Fig. 2, inset).

References

Cwilong, B. M. Sublimation in a Wilson chamber. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 190, 137–143 (1947).

Skripov, V. P. & Pavlov, P. A. Explosive boiling of liquids and fluctuation nucleus formation. High Temp. 8, 782–787 (1970).

Zheng, Q., Durben, D. J., Wolf, G. H. & Angell, C. A. Liquids at large negative pressures: Water at the homogeneous nucleation limit. Science 254, 829–832 (1991).

Caupin, F. & Herbert, E. Cavitation in water: A review. C. R. Phys. 7, 1000–1017 (2006).

Manka, A. A. et al. Homogeneous water nucleation in a laminar flow diffusion chamber. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 244505 (2010).

Wilson, P. W., Osterday, K. E., Heneghan, A. F. & Haymet, A. D. J. Type I antifreeze proteins enhance ice nucleation above certain concentrations. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 34741–34745 (2010).

Knezic, D., Zaccaro, J. & Myerson, A. S. Nucleation induction time in levitated droplets. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 10672–10677 (2004).

Caupin, F. Liquid-vapor interface, cavitation, and the phase diagram of water. Phys. Rev. E 71, 051605 (2005).

Debenedetti, P. G. Metastable Liquids (Princeton Univ. Press, 1996).

Alvarenga, A. D., Grimsditch, M. & Bodnar, R. J. Elastic properties of water under negative pressures. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 8392–8396 (1993).

Davitt, K., Arvengas, A. & Caupin, F. Water at the cavitation limit: Density of the metastable liquid and size of the critical bubble. Euro Phys. Lett. 90, 16002 (2010).

Mercury, L., Jamme, F. & Dumas, P. Infra-red imaging of bulk water and water–solid interfaces under stable and metastable conditions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 2864–2874 (2012).

Oxtoby, D. W. & Kashchiev, D. A general relation between the nucleation work and the size of the nucleus in multicomponent nucleation. J. Chem. Phys. 100, 7665–7671 (1994).

Speedy, R. J. Stability-limit conjecture. An interpretation of the properties of water. J. Phys. Chem. 86, 982–991 (1982).

Poole, P. H., Sciortino, F., Essmann, U. & Stanley, H. E. Phase behaviour of metastable water. Nature 360, 324–328 (1992).

Henderson, S. J. & Speedy, R. J. Temperature of maximum density in water at negative pressure. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 3062–3068 (1987).

IAPWS. Release on the surface tension of ordinary water substance (International Association for the Properties of Water and Steam, 1994); available via http://www.iapws.org/relguide/surf.pdf.

Green, J. L., Durben, D. J., Wolf, G. H. & Angell, C. A. Water and solutions at negative pressure: Raman spectroscopic study to −80 megapascals. Science 249, 649–652 (1990).

Tolman, R. C. The effect of droplet size on surface tension. J. Chem. Phys. 17, 333–337 (1949).

Block, B. J., Das, S. K., Oettel, M., Virnau, P. & Binder, K. Curvature dependence of surface free energy of liquid drops and bubbles: A simulation study. J. Chem. Phys. 133, 154702 (2010).

IAPWS. Revised release on the IAPWS formulation 1995 for the thermodynamic properties of ordinary water substance for general and scientific use (International Association for the Properties of Water and Steam, 2009); available via http://www.iapws.org/relguide/IAPWS95-Rev.pdf.

Shmulovich, K. I., Mercury, L., Thiéry, R., Ramboz, C. & El Mekki, M. Experimental superheating of water and aqueous solutions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 2457–2470 (2009).

Bodnar, R. & Sterner, S. Synthetic fluid inclusions in natural quartz. II. Application to PVT studies. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 49, 1855–1859 (1985).

Takahashi, M., Izawa, E., Etou, J. & Ohtani, T. Kinetic characteristic of bubble nucleation in superheated water using fluid inclusions. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 71, 2174–2177 (2002).

Blander, M. & Katz, J. Bubble nucleation in liquids. AIChE J. 21, 833–848 (1975).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. D. Stroock and C. Valeriani for helpful discussions. This research has been financially supported by the ERC under the European Community’s FP7 Grant Agreement 240113, and by Agence Nationale de la Recherche ANR Grant 09-BLAN-0404-01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.C. designed the study, M.E.M.A. selected the inclusion, M.E.M.A. and C.R. performed the experiments, F.C. analysed the data with contributions from J-F.L. and M.E.M.A., and F.C. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information (PDF 225 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Azouzi, M., Ramboz, C., Lenain, JF. et al. A coherent picture of water at extreme negative pressure. Nature Phys 9, 38–41 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2475

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2475

This article is cited by

-

Extreme thermodynamics in nanolitre volumes through stimulated Brillouin–Mandelstam scattering

Nature Physics (2023)

-

A nanoscale view of the origin of boiling and its dynamics

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Heterogeneous cavitation from atomically smooth liquid–liquid interfaces

Nature Physics (2022)

-

Non-contact optical characterization of negative pressure in hydrogel voids and microchannels

Frontiers of Optoelectronics (2022)

-

Water cavitation from ambient to high temperatures

Scientific Reports (2021)