Abstract

Exotic electronic states resulting from entangled spin and orbital degrees of freedom are hallmarks of strongly correlated f-electron systems. A spectacular example is the so-called hidden-order (HO) phase transition1 in the heavy-electron metal URu2Si2, which is characterized by the huge amount of entropy lost at THO=17.5 K (refs 2, 3). However, no evidence of magnetic/structural phase transition has been found below THO so far. The origin of the HO phase transition has been a long-standing mystery in condensed-matter physics. Here, on the basis of a first-principles theoretical approach, we examine the complete set of multipole correlations allowed in this material. The results uncover that the HO parameter is a rank-5 multipole (dotriacontapole) order with nematic E− symmetry, which exhibits staggered pseudospin moments along the [110] direction. This naturally provides comprehensive explanations of all key features in the HO phase including anisotropic magnetic excitations, the nearly degenerate antiferromagnetic-ordered state and spontaneous rotational-symmetry breaking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

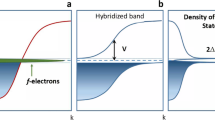

In the rare-earth and actinide compounds, f electrons behave like well-localized moments at high temperatures. As the temperature is lowered, f electrons begin to delocalize owing to the hybridization with conduction electron wavefunctions. At yet lower temperatures the f electrons become itinerant, forming a narrow conduction band with heavy effective electron mass, which is largely enhanced from the free-electron mass. Notable many-body effects within the narrow band lead to a plethora of fascinating physical phenomena including multipole order, quantum phase transition and unconventional superconductivity. Among them, perhaps the appearance of a HO state in URu2Si2 is one of the most mysterious phenomena. Identification of the microscopic order parameter and mechanism that drives the HO transition continues to be a central question in strongly correlated f-electron systems1.

There are several unique features that seem to be clues for understanding the HO in URu2Si2. In the paramagnetic state above THO, the magnetic susceptibility exhibits the Ising-like anisotropy2,4. In the HO state below THO, an electronic excitation gap is formed on a large portion of the Fermi surface5,6 (FS) and most of the carriers disappear7,8. Closely related to this, the gap formation also occurs in the magnetic excitation spectra at commensurate and incommensurate wave numbers, QC=(0 0 1) and QIC=(0.6 0 0), respectively, as revealed by the neutron inelastic scattering9,10,11. The HO ground state changes to the large-moment antiferromagnetic (AFM) state with the ordering vector QC on applying hydrostatic pressure12,13, but the FS has a striking similarity between these different phases14,15, implying that the HO is nearly degenerate with the AFM order. The magnetic torque measurements reveal the nematicity, which breaks the in-plane rotational (tetragonal) symmetry in the HO16. The challenge for the theory has been to identify the order parameter that explains all of the above key features.

The theories that have been proposed to describe the HO state can be divided into two prevailing approaches; one is based on the localized 5f-electron model17,18,19,20,21,22,23 and the other the itinerant one24,25,26,27,28,29. Recent angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy results clearly demonstrate that all 5f electrons are itinerant30 and the crystalline electric field, which is a signature of the localized nature, has never been observed. Moreover, the nuclear magnetic resonance measurements31 show a formation of the coherent heavy-electron state well above THO. Therefore, it is natural to discuss the electronic structure on the basis of the itinerant picture. However, reliable calculation of the physical quantities by taking into account the complicated band structure is a difficult task. For this purpose, we use a state-of-the-art ab initio downfolding (Supplementary Section SI) and dissect the electronic structure obtained from the density-functional theory (DFT) calculations. The obtained tight-binding Hamiltonian is constructed from 56 orbitals of U 5f, U 6d, Ru 4d and Si 3p. Introducing the on-site Coulomb interactions between 5f electrons, we obtain a realistic itinerant model, that is, a 56-band Anderson-lattice model including the spin–orbit interaction. On the basis of this realistic model Hamiltonian, magnetic and multipole correlations are analysed by the random-phase approximation (RPA) and beyond. To account for the mass renormalization effect in the Fermi-liquid theory, the energy and temperature scale is reduced by a factor of 10 throughout this study2,14,15, which makes comparisons to the experiments straightforward.

Figure 1 shows the paramagnetic FS and the band structure near the Fermi level, respectively. The energy bands crossing the Fermi level have mainly the total angular momentum j=5/2 multiplet of U 5f. Each jz component of j=5/2 multiplet is coloured by weight. It turns out that each separated FS is mainly composed of a rather specific jz component without large mixing, except for the outer FS around the Z point (Fig. 1). Such a jz component map is quite useful in that we are able to capture valuable information such as which parts of the FS play an essential role for the HO formation. Indeed, the disentanglement of FS orbital characters has also been an important theoretical advance to understand the electronic properties in iron-pnictide superconductors32.

Red, green and blue colour gauges correspond to jz=±5/2, ±3/2 and ±1/2 components, respectively. The FS is constructed from two hole FSs around Z, and the other four electron FSs. Small (blue) electron pockets centred at X and Γ are constructed from the jz=±1/2 component, and the inner (green) hole pocket around Z is from jz=±3/2. The outer hole pocket around Z is a hybridized band between ±3/2 and ±5/2. The outer electron FS around Γ is mainly composed of jz=±5/2, and partially hybridized with ±1/2. Two outer FSs around Γand Z are partially nested with QC=(001) indicated by the arrow.

First we discuss the RPA analysis of rank-1 (dipole) correlation, which is the conventional static magnetic correlation. The regime with jz=±5/2, shown in red, in the outer FS around the Z point is well nested with the outer FS around the Γ point by the vector QC, as indicated by the arrow in Fig. 1 (ref. 33). This nesting gives rise to a sharp peak of the correlation parallel to the c axis (dipole Jz) at Z (0 0 1) shown in Fig. 2a. Another salient feature is the hump structure at around (0.6 0 0) and the equivalent points, whose Q-vectors coincide with QIC. We point out that these peak and hump structures in the paramagnetic phase are directly related to the magnetic excitation gap at QC and QIC in the HO phase11 because the gap opening occurs at the nested parts of the FS. We also note that the in-plane magnetic correlations, Jx and Jy, are not enhanced in contrast to Jz (Fig. 2b), which is also consistent with the Ising-like magnetic susceptibility2,4 and polarized-neutron measurements10.

a, Magnetic susceptibility for Jz in the qz=0 plane. b–f, Multipole correlations along the high-symmetry line for rank-1 dipole (b), rank-2 quadrupole (c), rank-3 octupole (d), rank-4 hexadecapole (e) and rank-5 dotriacontapole (f) basis functions. Off-diagonal correlations between different bases are also shown (red lines). g, Diagonalized multipole correlations as a function of temperature, where  . All of these correlations have been obtained within the RPA calculations for U=U′≃2.3 and J=J′=0 in units of 1/ρf, where ρf is the total f-electron density of states at the Fermi level.

. All of these correlations have been obtained within the RPA calculations for U=U′≃2.3 and J=J′=0 in units of 1/ρf, where ρf is the total f-electron density of states at the Fermi level.

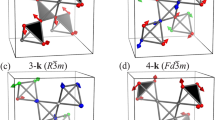

Next we examine the higher-rank multipole correlations. According to the group theory, there are 36 multipole moments up to the fifth rank in j=5/2 subspace (Supplementary Table S1). Figure 2c–f shows the correlations between the basis functions belonging to rank 2 (quadrupole), 3 (octupole), 4 (hexadecapole) and 5 (dotriacontapole), respectively. What is remarkable is that as in the case for the dipole Jz, the QC correlation at the Z point is strongly enhanced in some cases such as O20 (rank 2), Hx(y)b (rank 4), D4 (rank 5) and so on. Generally, these bases are mixed in the tetragonal symmetry, as shown by finite off-diagonal terms (red lines). The multipole correlations obtained by the diagonalization are depicted in Fig. 2g, in which each correlation at QC is classified by the irreducible representations and the dominant component is denoted in parentheses (Supplementary Section SIII). At low temperatures, A2−(Jz), E−(Dx(y)) and A1−(D4) symmetries exhibit the first, second and third strongest enhancement. The first and the last two correspond to the AFM and dotriacontapole states, respectively. Within the RPA, the AFM state always overcomes the dotriacontapole states. To go beyond the RPA, we consider a staggered particle–hole pairing (generalized multipole orders at the Z point) mediated by the RPA fluctuation from an analogy with unconventional superconductivity (Supplementary Section SIV). This corresponds to the inclusion of the mode–mode coupling. From an analogue of the superconducting gap equation for the staggered ordering, we calculate the maximum eigenvalue λ. The corresponding multipole correlation increases proportionally to ∼1/(1−λ), and then λ=1 provides the transition temperature. The temperature dependence of λ of each symmetry is shown in Fig. 3a. As the temperature is lowered, λ of E−(Dx(y)) is most strongly enhanced and the condition λ=1 is fulfilled at finite temperature, indicating a phase transition to the E−(Dx(y))state. We emphasize that E−(Dx(y)) symmetry breaks the in-plane four-fold symmetry, which naturally accounts for the nematicity observed in the magnetic torque results16,34. In addition, the E−(Dx(y)) state breaks the time-reversal symmetry, which is consistent with the nuclear magnetic resonance measurements31. These lead us to conclude that the HO is E−(Dx(y)) dotriacontapole order.

a, Temperature dependence of the maximum eigenvalue λ in an analogue of the superconducting gap equation for the staggered ordering for U=U′≃2.4 and J=J′=0. Note that λ=1 gives a phase transition temperature to the corresponding eigenstate. b, By increasing the Hund’s coupling J (Supplementary Fig. S4), the small difference in λ between the rank-5 E−(Dx(y)) and rank-1 A2−(Jz) states can be reversed, which may account for the pressure-induced AFM state. c, Temperature dependence of uniform susceptibilities parallel and perpendicular to the c axis calculated beyond the RPA. d, Schematic configurations of the ±5/2 pseudospin moments in the HO (left) and AFM (right) states are shown by the arrows. In both states, the pseudospins order antiferromagnetically along the c axis, but the direction of the staggered moments in the pseudospin space differs between the two: along [110] for the HO state and along [001] for the AFM state (centre).

The present calculations also reproduce well other key features of the HO, that is, near degeneracy of the HO and AFM states and the anisotropic temperature dependence of the uniform susceptibility. Figure 3a demonstrates that λ of E−(Dx(y)) is very close to that of A2−(Jz). This indicates that both states are nearly degenerate and a small perturbation can change the HO to the AFM state. Indeed, we can construct a phase diagram by tuning the interactions (Supplementary Fig. S4), which is consistent with the pressure–temperature phase diagram (Fig. 3b). The temperature dependence of the uniform susceptibility χc(0) parallel to the c axis exhibits a broad maximum at around 40 K, whereas χab(0) perpendicular to the c axis is smaller and nearly temperature independent (Fig. 3c), in good agreement with experiments2,4. The low-temperature decrease of χc(0) arises from the deep dip structure in the density of states near the Fermi level (Supplementary Fig. S1b). The Ising-like susceptibility including its temperature dependence has been discussed in terms of the crystalline electric field excitations of the localized 5f electrons so far. However, the present results demonstrate that the susceptibility can be well accounted for by the itinerant scenario.

Why is such a high-rank multipole state (rank 5) with E−(Dx(y)) symmetry realized in URu2Si2? Similar high-rank multipole states have been proposed already; a rank-4 A2+ state by the DFT+DMFT (dynamical mean field theory) method20, and a rank-5 A2− state by the DFT+U method27. However, these states obtained in the strong correlation limit are inconsistent with the nematic behaviour34. Detailed comparisons with other proposed HO parameters are listed in Supplementary Table S2. In our approach from the itinerant limit, the FS nesting with the QC vector plays an essential role in the multipole fluctuations. What is crucially important is that the FS regions connected by this QC are dominated by the ±5/2 components, as shown in Fig. 1. In this situation, we can consider a subspace consisting of only two components jz=5/2 and −5/2, which allows us to map jz=±5/2 to pseudospin ↑ and ↓. Then the dipole Jz is described by the Pauli matrix σz spanned in the pseudospin space, as it has only diagonal elements corresponding to  . In the same way, Dx(y) is given by σx(y), representing off-diagonal components describing the

. In the same way, Dx(y) is given by σx(y), representing off-diagonal components describing the  transition (Supplementary Section SV), which accompanies the angular momentum change of 5ℏ allowed only in rank 5. In this pseudospin space, the staggered Jz state corresponds to the Néel order along the caxis. On the other hand, the Dx(y) state corresponds to the in-plane order breaking the rotational symmetry, where in-plane pseudospin moments are antiferromagnetically coupled along the c axis (Fig. 3d). Thus, the pressure-induced first-order transition from the HO to AFM state can be explained by the pseudospin staggered moment flip from the in-plane to the out-of-plane direction. The experimentally observed nematicity along the [110] direction corresponds to the linear combination

transition (Supplementary Section SV), which accompanies the angular momentum change of 5ℏ allowed only in rank 5. In this pseudospin space, the staggered Jz state corresponds to the Néel order along the caxis. On the other hand, the Dx(y) state corresponds to the in-plane order breaking the rotational symmetry, where in-plane pseudospin moments are antiferromagnetically coupled along the c axis (Fig. 3d). Thus, the pressure-induced first-order transition from the HO to AFM state can be explained by the pseudospin staggered moment flip from the in-plane to the out-of-plane direction. The experimentally observed nematicity along the [110] direction corresponds to the linear combination  of the two-fold degenerate Dx and Dy. The HO parameter is then represented by

of the two-fold degenerate Dx and Dy. The HO parameter is then represented by

where fk α is an annihilation operator for an f electron with momentum k and pseudospin α. It should be noted that under in-plane 180° rotation, the pseudospins change their direction, which discriminates this state from a nematic phase in the strict sense. However, its staggered nature leads to the two-fold nematic symmetry of the bulk susceptibility as observed experimentally.

Figure 4a shows the FS in the HO and AFM states, which is calculated by applying the effective multipole field so as to open the gap of 4 meV observed by scanning tunnelling microscopy5,6. The lattice doubling in the AFM phase with QC also occurs in the HO phase. Most of the FS having jz=±5/2 components disappears as a result of the gap opening at the nested parts of the paramagnetic FS. Around the Γ-point, small electron and large hole (α) pockets, the FS with a cage-like structure and four electron pockets (β) exist. The FS in the HO phase bears a striking resemblance to that in the AFM state (Supplementary Section SVII), consistent with the quantum oscillation measurements. However, the broken four-fold symmetry in the HO state can be seen clearly in the FS with a cage-like structure (Fig. 4b), in sharp contrast to the AFM state.

a, Two-dimensional cut of FSs at kz=0 in the E−(D[110]) and A2− states. The Brillouin zone is folded with QC=(001). The D[110] state (left panel) exhibits the in-plane four-fold symmetry breaking, which can be most easily seen in the cage FS. Two FSs around M (blue and green lines in the right bottom) in the D[110] state have almost no splitting along XM, which is in contrast to the large splitting found for the A2− AFM and the E+ state (Supplementary Fig. S7). b, Band dispersion in the D[110] state along the ΓM line. The left panel highlights the excitation gap of ∼4 meV (arrow). The magnification near the cage FS (right panel) shows a pronounced anisotropic ΓM dispersion between Σ (red) and Σ′ (green).

The present approach based on the first-principles calculation is able to give a comprehensive explanation to the problem of HO, which has been a quarter-century mystery. Why has the HO been hidden for a long time? The reason is that in conventional experimental techniques, such as resonant X-ray and neutron measurements, extremely high-resolution measurements should be required for the direct detection of the high-rank multipole order parameter. We also point out that the present rank-5 order induces a very tiny but finite in-plane dipole moment belonging to the same symmetry E−, which is roughly estimated as 10−2−10−3μB(Supplementary Section SVI). The detection of such a tiny moment remains a future issue. The itinerant multipole ordering with nematicity revealed in the present study is a new type of electron ordering, which is expected to be ubiquitously present in strongly correlated electron systems when spin and orbital degrees of freedom are entangled.

References

Mydosh, J. A. & Oppeneer, P. M. Colloquium: Hidden order, superconductivity and magnetism—the unsolved case of URu2Si2 . Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1301–1322 (2011).

Palstra, T. T. M. et al. Superconducting and magnetic transitions in the heavy fermion system URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 2727–2730 (1985).

Maple, M. B. et al. Partially gapped Fermi surface in the heavy-electron superconductor URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 185–188 (1986).

Ramirez, A. P. et al. Nonlinear susceptibility as a probe of tensor spin order in URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 2680–2683 (1992).

Schmidt, A. R. et al. Imaging the Fano lattice to ‘hidden order’ transition in URu2Si2 . Nature 465, 570–576 (2010).

Aynajian, P. et al. Visualizing the formation of the Kondo lattice and the hidden order in URu2Si2 . Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 10383 (2010).

Behnia, K. et al. Thermal transport in the hidden-order state of URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 156405 (2005).

Kasahara, Y. et al. Exotic superconducting properties in the electron-hole-compensated heavy-Fermi semimetal URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 116402 (2007).

Broholm, C. et al. Magnetic excitations and ordering in the heavy-electron superconductor URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 1467–1470 (1987).

Bourdarot, F. et al. Precise study of the resonance at Q0=(1,0,0) in URu2Si2 . J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 79, 064719 (2010).

Wiebe, C. R. et al. Gapped itinerant spin excitations account for missing entropy in the hidden-order state of URu2Si2 . Nature Phys. 3, 96–99 (2007).

Amitsuka, H. et al. Pressure-temperature phase diagram of the heavy-electron superconductor URu2Si2 . J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 310, 214–220 (2007).

Hassinger, E. et al. Temperature-pressure phase diagram of URu2Si2 from resistivity measurements and ac calorimetry: Hidden order and Fermi-surface nesting. Phys. Rev. B 77, 115117 (2008).

Ohkuni, H. et al. Fermi surface properties and de Haas–van Alphen oscillation in both the normal and superconducting mixed states of URu2Si2 . Phil. Mag. B 79, 1045–1077 (1999).

Hassinger, E. et al. Similarity of the Fermi surface in the hidden order state and in the antiferromagnetic state of URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 216409 (2010).

Okazaki, R. et al. Rotational symmetry breaking in the hidden order phase of URu2Si2 . Science 331, 439–442 (2011).

Santini, P. & Amoretti, G. Crystal field model of the magnetic properties of URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 1027–1030 (1994).

Chandra, P. et al. Hidden orbital order in the heavy fermion metal URu2Si2 . Nature 417, 831–834 (2002).

Kiss, A. & Fazekas, P. Group theory and octupolar order in URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. B 71, 054415 (2005).

Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Arrested Kondo effect and hidden order in URu2Si2 . Nature Phys. 5, 796–799 (2009).

Harima, H., Miyake, K. & Flouquet, J. Why the hidden order in URu2Si2 is still hidden one simple answer. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 79, 033705 (2010).

Kusunose, H. & Harima, H. On the hidden order in URu2Si2 antiferro hexadecapole order and its consequences. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 80, 084702 (2011).

Pépin, C. et al. A modulated spin liquid: A new paradigm for URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 106601 (2011).

Ikeda, H. & Ohashi, Y. Theory of unconventional spin density wave: A possible mechanism of the micromagnetism in U-based heavy fermion compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 3723–3726 (1998).

Varma, C. M. & Zhu, L. Helicity order: Hidden order parameter in URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 036405 (2006).

Elgazzar, S. et al. Hidden-order in URu2Si2 originates from Fermi surface gapping induced by dynamic symmetry breaking. Nature Mater. 8, 337–341 (2009).

Cricchio, F., Bultmark, F., Granäs, O. & Nordström, L. Itinerant magnetic multipole moments of rank five as the hidden order in URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 107202 (2009).

Dubi, Y. & Balatsky, A.V. Hybridization wave as the hidden order in URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 086401 (2011).

Fujimoto, S. Spin nematic state as a candidate of the hidden order phase of URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 196407 (2011).

Kawasaki, I. et al. Band structure and Fermi surface of URu2Si2 studied by soft X-ray angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 83, 235121 (2011).

Takagi, S. et al. No evidence for small-moment antiferromagnetism under ambient pressure in URu2Si2: Single-crystal 29Si NMR study. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 76, 033708 (2007).

Kuroki, K. et al. Unconventional pairing originating from the disconnected Fermi surfaces of superconducting LaFeAsO1−xFx . Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 087004 (2008).

Oppeneer, P. M. et al. Electronic structure theory of the hidden-order material URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. B 82, 205103 (2010).

Thalmeier, P. & Takimoto, T. Signatures of hidden-order symmetry in torque oscillations, elastic constant anomalies, and field-induced moments in URu2Si2 . Phys. Rev. B 83, 165110 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Ueda, K. Haule, G. Kotliar, M. Sigrist and T. M. Rice for helpful discussions and suggestions. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for the Global COE programme ‘The Next Generation of Physics, Spun from Universality and Emergence’, a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas ‘Heavy Electrons’ (20102002, 20102006) from MEXT, and KAKENHI from JSPS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.I. and R.A. developed a methodology for the DFT+RPA and beyond. M-T.S. analysed the fermiology in some ordered states. T.T. provided group-theoretical arguments of multipoles. H.I., T.S. and Y.M. wrote the text. All authors contributed to critical discussion of the physical interpretation of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information (PDF 6492 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ikeda, H., Suzuki, MT., Arita, R. et al. Emergent rank-5 nematic order in URu2Si2. Nature Phys 8, 528–533 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2330

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2330

This article is cited by

-

Quantum-well states at the surface of a heavy-fermion superconductor

Nature (2023)

-

Proximity to a critical point driven by electronic entropy in URu2Si2

npj Quantum Materials (2021)

-

Destabilization of hidden order in URu2Si2 under magnetic field and pressure

Nature Physics (2020)

-

A quantum liquid of magnetic octupoles on the pyrochlore lattice

Nature Physics (2020)

-

Unusual magnetic field-dependence of a possible hidden order phase

npj Quantum Materials (2017)