Abstract

Seeing macroscopic quantum states directly remains an elusive goal. Particles with boson symmetry can condense into quantum fluids, producing rich physical phenomena as well as proven potential for interferometric devices1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. However, direct imaging of such quantum states is only fleetingly possible in high-vacuum ultracold atomic condensates, and not in superconductors. Recent condensation of solid-state polariton quasiparticles, built from mixing semiconductor excitons with microcavity photons, offers monolithic devices capable of supporting room-temperature quantum states11,12,13,14 that exhibit superfluid behaviour15,16. Here we use microcavities on a semiconductor chip supporting two-dimensional polariton condensates to directly visualize the formation of a spontaneously oscillating quantum fluid. This system is created on the fly by injecting polaritons at two or more spatially separated pump spots. Although oscillating at tunable THz frequencies, a simple optical microscope can be used to directly image their stable archetypal quantum oscillator wavefunctions in real space. The self-repulsion of polaritons provides a solid-state quasiparticle that is so nonlinear as to modify its own potential. Interference in time and space reveals the condensate wavepackets arise from non-equilibrium solitons. Control of such polariton-condensate wavepackets demonstrates great potential for integrated semiconductor-based condensate devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Non-resonant optical pumping of a semiconductor microcavity in the strong coupling regime continuously injects incoherent carriers which rapidly cool and scatter into the mixed light–matter states known as polaritons. Above a certain pump threshold (10 mW at T=10 K) these polaritons Bose condense11,12,13. Because of the extreme nonlinearities caused by strong repulsion between polaritons, they are shifted to higher energies (blue-shifted) wherever the density is high, particularly at the pumped spot17,18. The polaritons thus feel an outward force and form an expanding polariton condensate19. Here we explore the novel effects that occur when two neighbouring polariton condensates interact. Instead of typical Josephson-junction coherent coupling phenomena20, new effects arise because of the quasiparticle interactions.

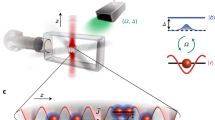

The decreasing density (and hence blue-shifts) away from two pumped spots induces a two-peaked potential profile (Fig. 1a). Surprisingly, on the line between the pump spots this potential seems parabolic, forming a potential trap like that of a simple harmonic oscillator, the quantum equivalent of a pendulum. The polaritons experiencing this potential redistribute in energy and space to occupy the simple harmonic oscillator (SHO) states (Fig. 1b). Because the polaritons can slowly leak through their confining mirrors into escaping photons, spatial images recorded on a camera (filtered at each emission energy) directly reveal the characteristic quantum wavefunctions (Fig. 1c), tens of micrometres across. Such extended coherent quantum states in a semiconductor are unprecedented to image in real time directly. The energy spacing between levels (Fig. 1d) is almost identical, En=ℏv(nSHO+1/2), and the increasing number of spatial nodes with ηSHO are clearly resolved. Along the line between pump spots, the wavefunctions fit very well the expected Hermite–Gaussian ψSHO(x) states (Fig. 1e). From such fits, the polariton potential is reconstructed (see Supplementary Information) as superimposed in Fig. 1b.

a, Experimental scheme with two 1 μm-diameter pump spots separated by 20 μm focused on the planar microcavity. The effective potential V (red) produces multiple condensates (grey image shows nSHO=3 mode). b, Real-space spectra along line between pump spots. c, Tomographic images of polariton emission (repulsive potential seen as dark circles around pump spots). Labelled according to nSHO assigned from d. d, Extracted mode energies versus quantum number. e, Hermite–Gaussian fit of ψSHOn=5(x) to image cross-section, dashed in c.

By controlling the spacing between the pump spots the shape and orientation of this SHO potential, V (r), can be directly modified in real time, thus changing the energy level spacing ℏv (Fig. 2a,b). In contrast if only one pump is present, the condensate polaritons flow out unhindered without relaxation (thus remaining at the blue-shifted polariton energy at the pump spot, Fig. 2c), whereas below threshold only incoherent emission is observed around each pump spot. Plotting the quantized energy levels for several pump separations, L, confirms their equal energy spacing and the predicted inverse dependence on separation (Fig. 2d). Although recent 1D versions of coherent polariton states observed in microcavities etched into wires19 do not seem to possess energies linked to any spatial scales, we suggest they arise in a similar fashion to here. As we show below, in 2D other significant features arise, including periodic oscillations of the polariton wavepackets and control of the polariton potential (Supplementary Information). Our crucial advance is the ability to manipulate independent condensates in 2D on a chip, using externally imprinted potentials that are not statically predefined.

a–c, Spatially resolved polariton energies on a line between pump spots (white arrows). In a and b, the pump separation L controls the SHO energy spacing. In c, no relaxation is observed. d, Ladder of SHO energies for three different pump separations L, with average energy spacings extracted in the inset. e, Time-averaged 2D simulation of the cGL equation for a 20 μm pump separation. f, Resulting time-averaged spectra along the dotted line in e.

If the pump separation is kept constant with the pump powers both increased (Supplementary Fig. S2a,b), then the spacing ℏv only increases slightly (Supplementary Fig. S2c,d). However the increasingly deep potential (from the pump-induced blue-shifts) increases the number of SHO states trapped inside. From the SHO model, increasing the polariton density, |ψ|2, gives a linear blue-shift, V max=g|ψ|2 (Supplementary Fig. S2d, right axis) producing the dependence as observed:

The SHO states are thus only resolved owing to the strong polariton repulsion (g)and the ultra-light polariton mass, m*=4.2×10−5me, (measured independently, see Supplementary Information). The polariton SHO states are populated differently under different conditions, with high pump powers and close pump separations favouring relaxation to the lower condensate SHO states. By using non-equal pump powers, asymmetric potentials can also be created (see Supplementary Information).

Our theoretical explanation starts with the mean-field equation21,22,23 for the lower polariton wavefunction, ψ, in the presence of a reservoir population, N, of optically injected hot excitons

which includes the polariton dispersion E(k)=ℏ2k2/2m*, the strength of the contact interaction potential g, an external potential V ext(r) that describes repulsive interactions with the reservoir, and the rate of polariton losses Γc. The details of the incoherent pump, reservoir excitons and relaxation due to collisions between condensed and non-condensed particles are included in P (see Supplementary Information). The net polariton potential V (r)=g|ψ(r,t)|2+V ext is produced by the repulsive interactions between polaritons themselves as well as with the reservoir excitons (N) close to the pump spots. This extension of the Gross–Pitaevskii equation is a complex Ginzburg–Landau (cGL) equation, a universal equation of mathematical physics describing the behaviour of systems in the vicinity of an instability and symmetry breaking24 and capable of spontaneous pattern formation. The non-equilibrium solution arises from the constant localized energy input at the pump spots together with polariton decay. Relaxation of polaritons by acoustic phonon emission is very slow25, and swamped by polariton–polariton and polariton–exciton scattering over the timescales discussed below. For two polaritons initially in SHO states (n1,n2) their mutual scattering to states (n1′,n2′) is only energy–phase matched if n1′+n2′=n1+n2 and E1′−E1=−{E2′−E2}. Scattering is thus most rapid if the energy separations between states are equal. At low powers, the potential is not parabolic, giving unequal energy spacings, and thus scattering is slower. At higher polariton densities, the scattering rate increases so that polariton relaxation populates lower energy states. The resulting new polariton density profile modifies the polariton potential, leading to more parabolic and equally spaced energies, thus speeding up scattering and feeding back positively. This contrasts with current theories for polariton condensates postulating a phonon scattering energy threshold21 (for which we see no evidence in experiment). The self-organized nature of the highly nonlinear polaritons is to produce the most rapid non-equilibrium energy flow through the system, by forming an SHO parabolic potential with an energy ladder that maximizes polariton relaxation. To our knowledge this is the first solid-state quasiparticle that is so nonlinear as to modify its own potential in this way, and links to current theories of nonequilibrium systems24.

We now demonstrate that as well as the individual SHO states being coherent condensates, they are also mutually coherent with each other. We compare first with the nonlinear Maxwell equations for optical pulses propagating inside a nonlinear medium with susceptibility χ so that iĖ={χ(1)+χ(3)|E|2}E. Whereas propagating optical pulses generate equally spaced sidebands through four-wave mixing26, condensate polaritons analogously parametrically scatter to give new coherent polariton states. In optics, such nonlinear dispersions can produce solitons and lead to mode-locking of laser cavity modes to produce trains of coherent intense pulses26. Here polaritonic wavepackets appear spontaneously, bouncing back and forth between the two pump spots, corresponding exactly to the spectral and spatial organization observed.

The real space images (not energy filtered) are split in a Michelson interferometer and recombined at an imaging camera (Fig. 3a–c), with the fringes aligned in the vertical direction. We map the fringe visibility and hence first order coherence g(1)(r,r,t) at the same spatial locations but separated in time (Fig. 3a–c, lower). As the time delay between the interfering images increases, the fringe visibility rapidly decreases everywhere but revives strongly after tr=±13 ps (Fig. 3c,d). This revival implies not only that the individual SHO states are phase coherent but that they are condensates with a stable phase relationship.

a–c, Real-space interference patterns for time delays shown. Pump spots separated by 20 μm, just off the right and left sides of the image. Lower images show extracted first-order coherence, g(1)(r,r,t). d, Fringe visibility averaged over each image versus Michelson interferometer time delay. e, Real-space tomographic image of the n=1 state for four pump spots (marked with the actual spot size, and taken at the energy of the dashed line in f). f, Energies across dashed line in e.

All observations above are accounted for by a single condensed coherent state, ψ, describing a polariton wavepacket in the quantum liquid oscillating back and forth with period tr producing the characteristic SHO sidebands observed. The oscillation period scales as expected with pump spatial separation (Supplementary Fig. S5). Indeed from equation (1),  (plotted as open circles), again consistent with the wavepacket oscillations. These 0.3–1.0 THz SHO sidebands, generated by a propagating condensate wavepacket moving through its own nonlinear potential, correspond to the frequency micro-combs recently observed in cavity optomechanics27.

(plotted as open circles), again consistent with the wavepacket oscillations. These 0.3–1.0 THz SHO sidebands, generated by a propagating condensate wavepacket moving through its own nonlinear potential, correspond to the frequency micro-combs recently observed in cavity optomechanics27.

The revival fringe amplitude at increasing time delays decays with a 40 ps lifetime, owing to coherent wavepacket dispersion, decay, dephasing and diffusion. This lifetime is, however, in good agreement with the coherent lifetime of the condensate found by converting the decay length of the ballistically expanding condensate into time. Wavepacket dispersion arises from the variation in the energy level spacing, Δ(ℏv)rms∼50 μeV, contributing 80 ps to the coherence decay. The temporal width of the condensate wavepacket corresponds to the number of SHO states observed, Δt≃tr/nSHO, (with nSHO∼10 well above threshold). In this picture, when the interacting condensates phase-lock, the resulting spatially modulated polaritons create polariton sidebands at the SHO states. In turn this further sharpens up the wavepacket extent and enhances the nonlinear polariton scattering. Such condensate polariton solitary waves are expected in cGL equations, and resemble the spatial solitons recently observed in atomic Bose–Einstein condensates (refs 28, 29). Higher-energy sidebands escape the SHO potential (unlike atomic Bose–Einstein condensates) leading to a modified solitary wave structure (note dark solitons are expected for the perfect 1D parabolic potential30). The behaviour observed is matched by our simulations of the cGL equation (Supplementary Information). Multiple wavepackets are observed bouncing back and forth (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. S4 and Supplementary Movie) which indeed produce spectra corresponding to the SHO sidebands (Fig. 2f).

This oscillating quantum liquid model explains another otherwise peculiar feature. Although polaritons are well-confined in between the pump spots, they are unconfined and even ejected by the potential (Fig. 1a) in the perpendicular direction. In spite of this, well-defined SHO wavefunctions (Fig. 1) are seen, which would not be expected for non-interacting 2D quantum quasiparticles. This is explained by the oscillating wavepacket, which is repeatedly amplified close to each pump spot on each pass.

The flexibility of the pump-induced polariton condensates easily allow full 2D confinement using extra pump spots. For instance, the lowest energy state in the four-pump square spot potential is fully confined in the x y plane (Fig. 3e,f), and selective polariton-condensate beams can be extracted. Thus polariton-condensate circuits can now be created on the fly merely by appropriate sculpting of the pumping geometry, which will lead to many future developments.

Methods

To produce the effects seen here, which persist all across the microcavity samples, high-quality growth is required. A 5λ/2 AlGaAs DBR microcavity is used for all experiments, with four sets of three quantum wells placed at the antinodes of the cavity electric field31. The cavity quality factor is measured to exceed Q>8,000, with transfer matrix simulations giving Q=2×104, corresponding to a cavity photon lifetime T=9 ps. Strong coupling is obtained with a characteristic Rabi splitting between upper and lower polariton energies of 9 meV. The microcavity wedge allows scanning across the sample to set the detuning between the cavity and photonic modes. All data presented here use a negative detuning of −5 meV, although other negative detunings give similar results. Excitation is provided by a single-mode narrow-linewidth CW laser, focused to 1 μm diameter spots through a 0.7 numerical aperture lens, and tuned to the first spectral dip at energies above the high-reflectivity mirror stopband at 750 nm. To prevent unwanted sample heating the pump laser is chopped at 100 Hz with an on/off ratio of 1:30.

The sample is held at cryogenic temperatures below 10 K, although similar effects are seen at higher temperatures. Images are recorded on an uncooled Si CCD camera in the magnified image plane, while spectra are recorded through a 0.55 m monochromator with a liquid-nitrogen-cooled CCD. Tomography uses a computer-controlled mirror selecting the line illumination of the front aperture of the monochromator. The Michelson interferometer uses retroreflectors mounted on delay stages to control the relative temporal separation of the interference. The pump laser is spectrally filtered out of all images. The fringe visibility, and hence first-order coherence, is mapped by extracting the first-order diffraction from the Fourier transformed images produced in the image plane after the Michelson interferometer. These are normalized to the corresponding zeroth-order diffraction and then transformed back into real space images.

References

Anderson, M. H. et al. Observation of Bose–Einstein condensation in a dilute atomic vapour. Science 269, 198–201 (1995).

Davis, K. B. et al. Bose–Einstein condensation in a gas of sodium atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 3969–3973 (1995).

Andrews, M. R. et al. Observation of interference between two Bose–Einstein condensates. Science 275, 637–641 (1997).

Anderson, B. P. & Kasevich, M. A. Macroscopic quantum interference from atomic tunnel arrays. Science 282, 1686–1689 (1998).

Cataliotti, F. S. et al. Josephson junction arrays with Bose–Einstein condensates. Science 293, 843–846 (2001).

Gupta, S. et al. Contrast interferometry using Bose–Einstein condensates to measure h/m and α. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 140401 (2002).

Wang, Y. J. et al. Atom Michelson interferometer on a chip using a Bose–Einstein condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 090405 (2005).

Penrose, O. & Onsager, L. Bose Einstein condensation and liquid Helium. Phys. Rev. 104, 576–584 (1954).

Eisenstein, J. P. & MacDonald, A. H. Bose–Einstein condensation of excitons in bilayer electron systems. Nature 432, 691–694 (2004).

Lagoudakis, K. G. et al. Coherent oscillations in an exciton–polariton Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 120403 (2010).

Deng, H. et al. Condensation of semiconductor microcavity exciton polaritons. Science 298, 199–202 (2002).

Kasprzak, J. et al. Bose–Einstein condensation of exciton polaritons. Nature 443, 409–414 (2006).

Balili, R. et al. Bose–Einstein condensation of microcavity polaritons in trap. Science 316, 1007–1010 (2007).

Christopoulos, C. et al. Room-temperature polariton lasing in semiconductor microcavities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 126405 (2007).

Amo, A. et al. Collective fluid dynamics of a polariton condensate in a semiconductor microcavity. Nature 457, 291–295 (2009).

Amo, A. et al. Superfluidity of polaritons in semiconductor microcavities. Nature Phys. 5, 805–810 (2009).

Savvidis, P. G. et al. Angle-resonant stimulated polariton amplifier. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 1547–1550 (2000).

Kavokin, A., Baumberg, J. J., Malpuech, G. & Laussy, F. P. Microcavities (Oxford Univ. Press, 2007).

Wertz, E. et al. Spontaneous formation and optical manipulation of extended polariton condensates. Nature Phys. 6, 860–864 (2010).

Josephson, B. D. The discovery of tunnelling supercurrents. Rev. Mod. Phys. 46, 251–254 (1974).

Wouters, M., Liew, T. C. H. & Savona, V. Energy relaxation in one-dimensional polariton condensates. Phys. Rev. B 82, 245315 (2010).

Wouters, M. & Carusotto, I. Excitations in a nonequilibrium Bose–Einstein condensate of exciton polaritons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 140402 (2007).

Keeling, J. & Berloff, N. G. Spontaneous rotating vortex lattices in a pumped decaying condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 250401 (2008).

Aranson, I.S. & Kramer, L. The world of the complex Ginzburg–Landau equation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 99–143 (2002).

Tartakovskii, A. I. et al. Relaxation bottleneck and its suppression in semiconductor microcavities. Phys. Rev. B 62, R2283–R2286 (2000).

Saleh, B. E. A. & Teich, M. C. Fundamentals of Photonics (Wiley, 1991).

Kippenberg, T. J., Holzwarth, R. & Diddams, S. A. Microresonator-based optical frequency combs. Science 332, 555–559 (2011).

Burger, S. et al. Dark solitons in Bose–Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 5198–5201 (1999).

Strekker, K. E. et al. Formation and propagation of matter–wave soliton trains. Nature 417, 150–153 (2002).

Pelinovsky, D.E., Frantzeskakis, D.J. & Kevrekidis, P.G. Oscillations of dark solitons in trapped Bose–Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. E 72, 016615 (2005).

Tsintzos, S. I. A GaAs polariton light-emitting diode operating near room temperature. Nature 453, 372–375 (2008).

Acknowledgements

L. Vina for comments, and grants EPSRC EP/G060649/1, EU CLERMONT4 235114, EU INDEX 289968, Spanish MEC (MAT2008-01555) and Greek GSRT program Irakleitos II. G.T. acknowledges financial support from an FPI scholarship of the Spanish MICINN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.T. and G.C. performed the spectroscopy experiments, and together with J.J.B. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. P.G.S. contributed to the preparation of the manuscript and together with P.T., T.G. and Z.H. designed and grew the microcavity samples, providing characterization spectroscopy to sustain high-quality performance. N.G.B. devised, coded, and carried out the modelling simulations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information (PDF 585 kb)

Supplementary Movie

Supplementary Movie 1 (MOV 18817 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tosi, G., Christmann, G., Berloff, N. et al. Sculpting oscillators with light within a nonlinear quantum fluid. Nature Phys 8, 190–194 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2182

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2182

This article is cited by

-

Non-equilibrium Bose–Einstein condensation in photonic systems

Nature Reviews Physics (2022)

-

Optically trapped room temperature polariton condensate in an organic semiconductor

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Quantum fluids of light in all-optical scatterer lattices

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Synthetic band-structure engineering in polariton crystals with non-Hermitian topological phases

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Single-shot condensation of exciton polaritons and the hole burning effect

Nature Communications (2018)