Abstract

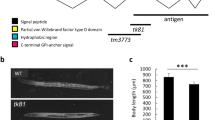

Dendrites from a single neuron may be highly branched but typically do not overlap. Self-avoidance behavior has been shown to depend on cell-specific membrane proteins that trigger mutual repulsion. Here we report the unexpected discovery that a diffusible cue, the axon guidance protein UNC-6 (Netrin), is required for self-avoidance of sister dendrites from the PVD nociceptive neuron in Caenorhabditis elegans. We used time-lapse imaging to show that dendrites fail to withdraw upon mutual contact in the absence of UNC-6 signaling. We propose a model in which the UNC-40 (Deleted in Colorectal Cancer; DCC) receptor captures UNC-6 at the tips of growing dendrites for interaction with UNC-5 on the apposing branch to induce mutual repulsion. UNC-40 also responds to dendritic contact through another pathway that is independent of UNC-6. Our findings offer a new model for how an evolutionarily conserved morphogenic cue and its cognate receptors can pattern a fundamental feature of dendritic architecture.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Jan, Y.N. & Jan, L.Y. Branching out: mechanisms of dendritic arborization. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 316–328 (2010).

Grueber, W.B. & Sagasti, A. Self-avoidance and tiling: mechanisms of dendrite and axon spacing. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a001750 (2010).

Corty, M.M., Matthews, B.J. & Grueber, W.B. Molecules and mechanisms of dendrite development in Drosophila. Development 136, 1049–1061 (2009).

Hattori, D., Millard, S., Wojtowicz, W. & Zipursky, S. Dscam-mediated cell recognition regulates neural circuit formation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 24, 597–620 (2008).

Hughes, M.E. et al. Homophilic Dscam interactions control complex dendrite morphogenesis. Neuron 54, 417–427 (2007).

Matthews, B.J. et al. Dendrite self-avoidance is controlled by Dscam. Cell 129, 593–604 (2007).

Matsubara, D., Horiuchi, S.Y., Shimono, K., Usui, T. & Uemura, T. The seven-pass transmembrane cadherin Flamingo controls dendritic self-avoidance via its binding to a LIM domain protein, Espinas, in Drosophila sensory neurons. Genes Dev. 25, 1982–1996 (2011).

Long, H., Ou, Y., Rao, Y. & van Meyel, D.J. Dendrite branching and self-avoidance are controlled by Turtle, a conserved IgSF protein in Drosophila. Development 136, 3475–3484 (2009).

Zipursky, S.L. & Sanes, J.R. Chemoaffinity revisited: dscams, protocadherins, and neural circuit assembly. Cell 143, 343–353 (2010).

Wadsworth, W.G., Bhatt, H. & Hedgecock, E. Neuroglia and pioneer neurons express UNC-6 to provide global and local netrin cues for guiding migrations in C. elegans. Neuron 16, 35–46 (1996).

Serafini, T. et al. The netrins define a family of axon outgrowth-promoting proteins homologous to C. elegans UNC-6. Cell 78, 409–424 (1994).

Mitchell, K.J. et al. Genetic analysis of Netrin genes in Drosophila: Netrins guide CNS commissural axons and peripheral motor axons. Neuron 17, 203–215 (1996).

Hiramoto, M., Hiromi, Y., Giniger, E. & Hotta, Y. The Drosophila Netrin receptor Frazzled guides axons by controlling Netrin distribution. Nature 406, 886–889 (2000).

Keleman, K. & Dickson, B. Short- and long-range repulsion by the Drosophila Unc5 netrin receptor. Neuron 32, 605–617 (2001).

Colon-Ramos, D.A., Margeta, M. & Shen, K. Glia promote local synaptogenesis through UNC-6 (netrin) signaling in C. elegans. Science 318, 103–106 (2007).

Teichmann, H.M. & Shen, K. UNC-6 and UNC-40 promote dendritic growth through PAR-4 in Caenorhabditis elegans neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 165–172 (2010).

Park, J. et al. A conserved juxtacrine signal regulates synaptic partner recognition in Caenorhabditis elegans. Neural Develop. 6, 28 (2011).

Chan, S.S. et al. UNC-40, a C. elegans homolog of DCC (Deleted in Colorectal Cancer), is required in motile cells responding to UNC-6 netrin cues. Cell 87, 187–195 (1996).

Leonardo, E.D. et al. Vertebrate homologues of C. elegans UNC-5 are candidate netrin receptors. Nature 386, 833–838 (1997).

Smith, C.J. et al. Time-lapse imaging and cell-specific expression profiling reveal dynamic branching and molecular determinants of a multi-dendritic nociceptor in C. elegans. Dev. Biol. 345, 18–33 (2010).

Albeg, A. et al. C. elegans multi-dendritic sensory neurons: morphology and function. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 46, 308–317 (2010).

Oren-Suissa, M., Hall, D.H., Treinin, M., Shemer, G. & Podbilewicz, B. The fusogen EFF-1 controls sculpting of mechanosensory dendrites. Science 328, 1285–1288 (2010).

Hall, D.H. & Treinin, M. How does morphology relate to function in sensory arbors? Trends Neurosci. 34, 443–451 (2011).

Aguirre-Chen, C., Bülow, H.E. & Kaprielian, Z. C. elegans bicd-1, homolog of the Drosophila dynein accessory factor Bicaudal D, regulates the branching of PVD sensory neuron dendrites. Development 138, 507–518 (2011).

Ishii, N., Wadsworth, W., Stern, B., Culotti, J. & Hedgecock, E. UNC-6, a laminin-related protein, guides cell and pioneer axon migrations in C. elegans. Neuron 9, 873–881 (1992).

Schwarz, V., Pan, J., Voltmer-Irsch, S. & Hutter, H. IgCAMs redundantly control axon outgrowth in Caenorhabditis elegans. Neural Develop. 4, 13 (2009).

Adler, C.E., Fetter, R. & Bargmann, C. UNC-6/Netrin induces neuronal asymmetry and defines the site of axon formation. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 511–518 (2006).

Watson, J.D. et al. Complementary RNA amplification methods enhance microarray identification of transcripts expressed in the C. elegans nervous system. BMC Genomics 9, 84 (2008).

Xu, Z., Li, H. & Wadsworth, W. The roles of multiple UNC-40 (DCC) receptor-mediated signals in determining neuronal asymmetry induced by the UNC-6 (netrin) ligand. Genetics 183, 941–949 (2009).

Yang, L., Garbe, D. & Bashaw, G. A frazzled/DCC-dependent transcriptional switch regulates midline axon guidance. Science 324, 944–947 (2009).

Tsalik, E.L. & Hobert, O. Functional mapping of neurons that control locomotory behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurobiol. 56, 178–197 (2003).

Eastman, C., Horvitz, H.R. & Jin, Y. Coordinated transcriptional regulation of the unc-25 glutamic acid decarboxylase and the unc-47 GABA vesicular transporter by the Caenorhabditis elegans UNC-30 homeodomain protein. J. Neurosci. 19, 6225–6234 (1999).

Leung-Hagesteijn, C. et al. UNC-5, a transmembrane protein with immunoglobulin and thrombospondin type 1 domains, guides cell and pioneer axon migrations in C. elegans. Cell 71, 289–299 (1992).

Killeen, M. et al. UNC-5 function requires phosphorylation of cytoplasmic tyrosine 482, but its UNC-40-independent functions also require a region between the ZU-5 and death domains. Dev. Biol. 251, 348–366 (2002).

Asakura, T., Ogura, K. & Goshima, Y. UNC-6 expression by the vulval precursor cells of Caenorhabditis elegans is required for the complex axon guidance of the HSN neurons. Dev. Biol. 304, 800–810 (2007).

Bashaw, G.J. & Goodman, C.S. Chimeric axon guidance receptors: the cytoplasmic domains of slit and netrin receptors specify attraction versus repulsion. Cell 97, 917–926 (1999).

Gitai, Z., Yu, T., Lundquist, E., Tessier-Lavigne, M. & Bargmann, C. The netrin receptor UNC-40/DCC stimulates axon attraction and outgrowth through enabled and, in parallel, Rac and UNC-115/AbLIM. Neuron 37, 53–65 (2003).

Hiramoto, M. & Hiromi, Y. ROBO directs axon crossing of segmental boundaries by suppressing responsiveness to relocalized Netrin. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 58–66 (2006).

Kuzina, I., Song, J.K. & Giniger, E. How Notch establishes longitudinal axon connections between successive segments of the Drosophila CNS. Development 138, 1839–1849 (2011).

Alexander, M. et al. An UNC-40 pathway directs postsynaptic membrane extension in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 136, 911–922 (2009).

MacNeil, L., Hardy, W., Pawson, T., Wrana, J. & Culotti, J. UNC-129 regulates the balance between UNC-40 dependent and independent UNC-5 signaling pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 150–155 (2009).

Merz, D.C., Zheng, H., Killeen, M.T., Krizus, A. & Culotti, J.G. Multiple signaling mechanisms of the UNC-6/netrin receptors UNC-5 and UNC-40/DCC in vivo. Genetics 158, 1071–1080 (2001).

Chang, C. et al. MIG-10/lamellipodin and AGE-1/PI3K promote axon guidance and outgrowth in response to slit and netrin. Curr. Biol. 16, 854–862 (2006).

Quinn, C.C., Pfeil, D. & Wadsworth, W. CED-10/Rac1 mediates axon guidance by regulating the asymmetric distribution of MIG-10/lamellipodin. Curr. Biol. 18, 808–813 (2008).

Fleming, T. et al. The role of C. elegans Ena/VASP homolog UNC-34 in neuronal polarity and motility. Dev. Biol. 344, 94–106 (2010).

Grueber, W.B. & Sagasti, A. Self-avoidance and tiling: mechanisms of dendrite and axon spacing. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a001750 (2010).

Emoto, K., Parrish, J., Jan, L. & Jan, Y.-N. The tumour suppressor Hippo acts with the NDR kinases in dendritic tiling and maintenance. Nature 443, 210–213 (2006).

Brenner, S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94 (1974).

Poon, V.Y., Klassen, M. & Shen, K. UNC-6/netrin and its receptor UNC-5 locally exclude presynaptic components from dendrites. Nature 455, 669–673 (2008).

Sulston, J.E. & Horvitz, H. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 56, 110–156 (1977).

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Bargmann (Rockefeller University) for unc-86∷UNC-40∷GFP, hsp16.2∷UNC-6∷HA and the CX6488 strain; W. Wadsworth (Rutgers University) for the pIM97 unc-6 expression construct and unc-6(rh46); K. Shen (Stanford University) for constructs used to make pCJS01, F49H12.4∷gateway∷mcherry; P. Roy (University of Toronto) for the unc-40(e271) sequence; Y. Goshima (Yokohama City University) for ghIs9; J. Culotti (Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto) for the unc-5 rescue construct and for the modified UNC-5 protein strains used for structure–function analysis and members of the D.M.M., R.B. and D.A.C.-R. laboratories for technical advice and for comments on the manuscript. Some of the strains used in this work were provided by the C. elegans Genetics Center, which is supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Research Resources. This work was supported by NIH R01 NS26115 (D.M.M.), NIH R21 NS06882 (D.M.M.), NIH F31 NS071801 (C.J.S.), NIH R00 NS057931 (D.A.C.-R.), the Klingenstein Foundation and an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation fellowship (D.A.C.-R.), and NIH MBRS SC3 GM089595 (M.K.V.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.J.S. and D.M.M. designed the experiments. C.J.S. performed experiments with advice from D.M.M. J.D.W. helped with the phenotypic analysis of UNC-6 signaling mutants. D.A.C.-R. and M.K.V. provided reagents to test the cell-specific requirement of UNC-40 and UNC-6 and provided advice. C.J.S. and D.M.M. wrote the paper with input from coauthors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–9, Supplementary Table 1 (PDF 870 kb)

Supplementary Movie 1

Wild-type self-avoidance. Time-lapse confocal movie of PVD::GFP in wild-type background. 3° dendrites contact but quickly retract (arrows). Note the intervening distance between 3O dendrites at the end of the movie is comparable to distance visualized in mature PVD neurons. Arrows indicate locations of contact-dependent self-avoidance. (MOV 8295 kb)

Supplementary Movie 2

Self-avoidance defect in unc-40(e271). Time-lapse confocal movie of PVD::GFP in unc-40(e271). 3° dendrites grow toward each other but upon contact fail to retract. Arrow indicates location of failed self-avoidance. (MOV 1892 kb)

Supplementary Movie 3

Self-avoidance defect in unc-5(e152). Imaging of unc-5(e152) shows PVD dendrites fail to retract after contact. Arrow indicates location of failed self-avoidance. (MOV 33275 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, C., Watson, J., VanHoven, M. et al. Netrin (UNC-6) mediates dendritic self-avoidance. Nat Neurosci 15, 731–737 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3065

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3065

This article is cited by

-

Quantitative modeling of regular retinal microglia distribution

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Deep learning-enabled analysis reveals distinct neuronal phenotypes induced by aging and cold-shock

BMC Biology (2020)

-

Dendritic tree extraction from noisy maximum intensity projection images in C. elegans

BioMedical Engineering OnLine (2014)

-

Loop formation and self-fasciculation of cortical axon using photonic guidance at long working distance

Scientific Reports (2014)

-

Neuronal aging: learning from C. elegans

Journal of Molecular Signaling (2013)