Abstract

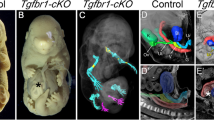

It is well established that retinal neurogenesis in mouse embryos requires the activation of Notch signaling, but is independent of the Wnt signaling pathway. We found that genetic inactivation of Sfrp1 and Sfrp2, two postulated Wnt antagonists, perturbs retinal neurogenesis. In retinas from Sfrp1−/−; Sfrp2−/− embryos, Notch signaling was transiently upregulated because Sfrps bind ADAM10 metalloprotease and downregulate its activity, an important step in Notch activation. The proteolysis of other ADAM10 substrates, including APP, was consistently altered in Sfrp mutants, whereas pharmacological inhibition of ADAM10 partially rescued the Sfrp1−/−; Sfrp2−/− retinal phenotype. Conversely, ectopic Sfrp1 expression in the Drosophila wing imaginal disc prevented the expression of Notch targets, and this was restored by the coexpression of Kuzbanian, the Drosophila ADAM10 homolog. Together, these data indicate that Sfrps inhibit the ADAM10 metalloprotease, which might have important implications in pathological events, including cancer and Alzheimer's disease.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hayward, P., Kalmar, T. & Arias, A.M. Wnt/Notch signalling and information processing during development. Development 135, 411–424 (2008).

Livesey, F.J. & Cepko, C.L. Vertebrate neural cell-fate determination: lessons from the retina. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 109–118 (2001).

Cho, S.H. & Cepko, C.L. Wnt2b/beta-catenin-mediated canonical Wnt signaling determines the peripheral fates of the chick eye. Development 133, 3167–3177 (2006).

Liu, H. et al. Ciliary margin transdifferentiation from neural retina is controlled by canonical Wnt signaling. Dev. Biol. 308, 54–67 (2007).

Fu, X., Sun, H., Klein, W.H. & Mu, X. Beta-catenin is essential for lamination but not neurogenesis in mouse retinal development. Dev. Biol. 299, 424–437 (2006).

Liu, C. & Nathans, J. An essential role for frizzled 5 in mammalian ocular development. Development 135, 3567–3576 (2008).

Liu, H., Mohamed, O., Dufort, D. & Wallace, V.A. Characterization of Wnt signaling components and activation of the Wnt canonical pathway in the murine retina. Dev. Dyn. 227, 323–334 (2003).

Bovolenta, P., Esteve, P., Ruiz, J.M., Cisneros, E. & Lopez-Rios, J. Beyond Wnt inhibition: new functions of secreted Frizzled-related proteins in development and disease. J. Cell Sci. 121, 737–746 (2008).

Satoh, W., Gotoh, T., Tsunematsu, Y., Aizawa, S. & Shimono, A. Sfrp1 and Sfrp2 regulate anteroposterior axis elongation and somite segmentation during mouse embryogenesis. Development 133, 989–999 (2006).

Trevant, B. et al. Expression of secreted frizzled related protein 1, a Wnt antagonist, in brain, kidney, and skeleton is dispensable for normal embryonic development. J. Cell. Physiol. 217, 113–126 (2008).

Satoh, W., Matsuyama, M., Takemura, H., Aizawa, S. & Shimono, A. Sfrp1, Sfrp2, and Sfrp5 regulate the Wnt/beta-catenin and the planar cell polarity pathways during early trunk formation in mouse. Genesis 46, 92–103 (2008).

Misra, K. & Matise, M.P. A critical role for sFRP proteins in maintaining caudal neural tube closure in mice via inhibition of BMP signaling. Dev. Biol. 337, 74–83 (2010).

Kobayashi, K. et al. Secreted Frizzled-related protein 2 is a procollagen C proteinase enhancer with a role in fibrosis associated with myocardial infarction. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 46–55 (2009).

He, W. et al. Exogenously administered secreted frizzled related protein 2 (Sfrp2) reduces fibrosis and improves cardiac function in a rat model of myocardial infarction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 21110–21115 (2010).

Lee, H.X., Ambrosio, A.L., Reversade, B. & De Robertis, E.M. Embryonic dorsal-ventral signaling: secreted frizzled-related proteins as inhibitors of tolloid proteinases. Cell 124, 147–159 (2006).

Muraoka, O. et al. Sizzled controls dorso-ventral polarity by repressing cleavage of the Chordin protein. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 329–338 (2006).

Mii, Y. & Taira, M. Secreted Frizzled-related proteins enhance the diffusion of Wnt ligands and expand their signalling range. Development 136, 4083–4088 (2009).

Kopan, R. & Ilagan, M.X. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell 137, 216–233 (2009).

Del Monte, G., Grego-Bessa, J., Gonzalez-Rajal, A., Bolos, V. & De La Pompa, J.L. Monitoring Notch1 activity in development: evidence for a feedback regulatory loop. Dev. Dyn. 236, 2594–2614 (2007).

Tokunaga, A. et al. Mapping spatio-temporal activation of Notch signaling during neurogenesis and gliogenesis in the developing mouse brain. J. Neurochem. 90, 142–154 (2004).

Kim, A.S., Lowenstein, D.H. & Pleasure, S.J. Wnt receptors and Wnt inhibitors are expressed in gradients in the developing telencephalon. Mech. Dev. 103, 167–172 (2001).

Jorissen, E. et al. The disintegrin/metalloproteinase ADAM10 is essential for the establishment of the brain cortex. J. Neurosci. 30, 4833–4844 (2010).

Hartmann, D. et al. The disintegrin/metalloprotease ADAM 10 is essential for Notch signaling but not for alpha-secretase activity in fibroblasts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 2615–2624 (2002).

Amour, A. et al. The in vitro activity of ADAM-10 is inhibited by TIMP-1 and TIMP-3. FEBS Lett. 473, 275–279 (2000).

Langton, K.P., Barker, M.D. & McKie, N. Localization of the functional domains of human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 and the effects of a Sorsby's fundus dystrophy mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16778–16781 (1998).

Ludwig, A. et al. Metalloproteinase inhibitors for the disintegrin-like metalloproteinases ADAM10 and ADAM17 that differentially block constitutive and phorbol ester–inducible shedding of cell surface molecules. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 8, 161–171 (2005).

Reiss, K. et al. ADAM10 cleavage of N-cadherin and regulation of cell-cell adhesion and beta-catenin nuclear signaling. EMBO J. 24, 742–752 (2005).

Riedle, S. et al. Nuclear translocation and signaling of L1-CAM in human carcinoma cells requires ADAM10 and presenilin/gamma-secretase activity. Biochem. J. 420, 391–402 (2009).

Lichtenthaler, S.F. Alpha-secretase in Alzheimer's disease: molecular identity, regulation and therapeutic potential. J. Neurochem. 116, 10–21 (2011).

Caillé, I. et al. Soluble form of amyloid precursor protein regulates proliferation of progenitors in the adult subventricular zone. Development 131, 2173–2181 (2004).

Stetler-Stevenson, W.G. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in cell signaling: metalloproteinase-independent biological activities. Sci. Signal. 1, re6 (2008).

Micchelli, C.A., Rulifson, E.J. & Blair, S.S. The function and regulation of cut expression on the wing margin of Drosophila: Notch, Wingless and a dominant-negative role for Delta and Serrate. Development 124, 1485–1495 (1997).

Uren, A. et al. Secreted frizzled-related protein-1 binds directly to Wingless and is a biphasic modulator of Wnt signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 4374–4382 (2000).

Lopez-Rios, J., Esteve, P., Ruiz, J.M. & Bovolenta, P. The Netrin-related domain of Sfrp1 interacts with Wnt ligands and antagonizes their activity in the anterior neural plate. Neural Develop. 3, 19 (2008).

Nolo, R., Abbott, L.A. & Bellen, H.J. Senseless, a Zn finger transcription factor, is necessary and sufficient for sensory organ development in Drosophila. Cell 102, 349–362 (2000).

Esteve, P. & Bovolenta, P. Secreted inducers in vertebrate eye development: more functions for old morphogens. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16, 13–19 (2006).

Wall, D.S. et al. Progenitor cell proliferation in the retina is dependent on Notch-independent Sonic hedgehog/Hes1 activity. J. Cell Biol. 184, 101–112 (2009).

Kubo, F. & Nakagawa, S. Hairy1 acts as a node downstream of Wnt signaling to maintain retinal stem cell–like progenitor cells in the chick ciliary marginal zone. Development 136, 1823–1833 (2009).

Morcillo, J. et al. Proper patterning of the optic fissure requires the sequential activity of BMP7 and SHH. Development 133, 3179–3190 (2006).

Muraguchi, T. et al. RECK modulates Notch signaling during cortical neurogenesis by regulating ADAM10 activity. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 838–845 (2007).

Campbell, C., Risueno, R.M., Salati, S., Guezguez, B. & Bhatia, M. Signal control of hematopoietic stem cell fate: Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog as the usual suspects. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 15, 319–325 (2008).

Edwards, D.R., Handsley, M.M. & Pennington, C.J. The ADAM metalloproteinases. Mol. Aspects Med. 29, 258–289 (2008).

Kuhn, P.H. et al. ADAM10 is the physiologically relevant, constitutive alpha-secretase of the amyloid precursor protein in primary neurons. EMBO J. 29, 3020–3032 (2010).

Mott, J.D. et al. Post-translational proteolytic processing of procollagen C-terminal proteinase enhancer releases a metalloproteinase inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 1384–1390 (2000).

Gavert, N. et al. Expression of L1-CAM and ADAM10 in human colon cancer cells induces metastasis. Cancer Res. 67, 7703–7712 (2007).

Matsuda, Y., Schlange, T., Oakeley, E.J., Boulay, A. & Hynes, N.E. WNT signaling enhances breast cancer cell motility and blockade of the WNT pathway by sFRP1 suppresses MDA-MB-231 xenograft growth. Breast Cancer Res. 11, R32 (2009).

Donmez, G., Wang, D., Cohen, D.E. & Guarente, L. SIRT1 suppresses beta-amyloid production by activating the alpha-secretase gene ADAM10. Cell 142, 320–332 (2010).

Torroja, C., Gorfinkiel, N. & Guerrero, I. Patched controls the Hedgehog gradient by endocytosis in a dynamin-dependent manner, but this internalization does not play a major role in signal transduction. Development 131, 2395–2408 (2004).

Tanimoto, H., Itoh, S., ten Dijke, P. & Tabata, T. Hedgehog creates a gradient of DPP activity in Drosophila wing imaginal discs. Mol. Cell 5, 59–71 (2000).

Rodriguez, J. et al. SFRP1 regulates the growth of retinal ganglion cell axons through the Fz2 receptor. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1301–1309 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We thank J.M. Ruiz for help with initial experiments and I. Dompablo for technical assistance, H. Bellen (Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute), T. Tabata (University of Tokyo), S. Campuzano (CSIC–Universidad Autónoma de Madrid) and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for Drosophila antibodies and stocks, and A. Ludwig (RWTH Aachen University) for the G1254023X compound. This work was supported by grants from the Spanish MICINN (BFU2007-61774), Fundación Mutual Madrileña (2006-0916), Comunidad Autonoma de Madrid (P-SAL-0190-2006), Programa Intramural Especial–CSIC and CIBERER intramural funds to P.B.; CSIC intramural funds to P.E.; grants BFU2008-03320/BMC and CSD2007-00008 from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación to I.G. and an institutional grant from Fundación Areces given to the Centro de Biología Molecular “Severo Ochoa” to I.G. and M.L.T.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.E. and A. Sandonìs performed most of the immunohistochemical, in situ hybridization and western blot analysis. A. Shimono generated the Sfrp knockout mice. M.C. and I.C. performed immunoprecipitation and binding assays. J.M. and J.A. designed and performed APP shedding experiments in CHO cells. I.G. designed and performed (with C.I.) the assays in Drosophila. S.M. contributed Sfrp1 and Sfrp2 in situ hybridization localization. S.G.-G. and M.L.T. contributed expertise in Notch signaling and flow cytometry. P.B. and P.E. conceived and supervised the study and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–4 (PDF 2986 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Esteve, P., Sandonìs, A., Cardozo, M. et al. SFRPs act as negative modulators of ADAM10 to regulate retinal neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci 14, 562–569 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2794

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2794

This article is cited by

-

Large-scale deep multi-layer analysis of Alzheimer’s disease brain reveals strong proteomic disease-related changes not observed at the RNA level

Nature Neuroscience (2022)

-

ADAM10 promotes cell growth, migration, and invasion in osteosarcoma via regulating E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling pathway and is regulated by miR-122-5p

Cancer Cell International (2020)

-

Sfrp1 deficiency makes retinal photoreceptors prone to degeneration

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Restoring Wnt/β-catenin signaling is a promising therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer’s disease

Molecular Brain (2019)

-

Sfrp3 modulates stromal–epithelial crosstalk during mammary gland development by regulating Wnt levels

Nature Communications (2019)