Abstract

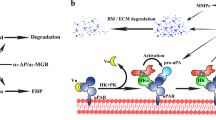

The N-terminal fragment of prolactin (16K PRL) inhibits tumor growth by impairing angiogenesis, but the underlying mechanisms are unknown. Here, we found that 16K PRL binds the fibrinolytic inhibitor plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), which is known to contextually promote tumor angiogenesis and growth. Loss of PAI-1 abrogated the antitumoral and antiangiogenic effects of 16K PRL. PAI-1 bound the ternary complex PAI-1–urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA)–uPA receptor (uPAR), thereby exerting antiangiogenic effects. By inhibiting the antifibrinolytic activity of PAI-1, 16K PRL also protected mice against thromboembolism and promoted arterial clot lysis. Thus, by signaling through the PAI-1–uPA–uPAR complex, 16K PRL impairs tumor vascularization and growth and, by inhibiting the antifibrinolytic activity of PAI-1, promotes thrombolysis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Accession codes

Change history

25 August 2014

In the version of this article initially published, it was stated that 16K PRL levels are increased in retinopathy, citing reference 10. However, this reference was cited incorrectly, and in fact another paper showed that 16K PRL levels are decreased in diabetic retinopathy. The error has been corrected in the HTML and PDF versions of the article.

References

Chung, A.S., Lee, J. & Ferrara, N. Targeting the tumour vasculature: insights from physiological angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 505–514 (2010).

Struman, I. et al. Opposing actions of intact and N-terminal fragments of the human prolactin/growth hormone family members on angiogenesis: an efficient mechanism for the regulation of angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1246–1251 (1999).

Clapp, C., Aranda, J., Gonzalez, C., Jeziorski, M.C. & Martinez de la Escalera, G. Vasoinhibins: endogenous regulators of angiogenesis and vascular function. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 17, 301–307 (2006).

Bentzien, F., Struman, I., Martini, J.F., Martial, J. & Weiner, R. Expression of the antiangiogenic factor 16K hPRL in human HCT116 colon cancer cells inhibits tumor growth in Rag1−/− mice. Cancer Res. 61, 7356–7362 (2001).

Kim, J. et al. Antitumor activity of the 16-kDa prolactin fragment in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 63, 386–393 (2003).

Kinet, V. et al. Antiangiogenic liposomal gene therapy with 16K human prolactin efficiently reduces tumor growth. Cancer Lett. 284, 222–228 (2009).

Nguyen, N.Q. et al. Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis establishment by adenovirus-mediated gene transfer delivery of the antiangiogenic factor 16K hPRL. Mol. Ther. 15, 2094–2100 (2007).

Tabruyn, S.P. et al. The angiostatic 16K human prolactin overcomes endothelial cell anergy and promotes leukocyte infiltration via nuclear factor-κB activation. Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 1422–1429 (2007).

Nguyen, N.Q. et al. The antiangiogenic 16K prolactin impairs functional tumor neovascularization by inhibiting vessel maturation. PLoS ONE 6, e27318 (2011).

Triebel, J. & Ramadori, G. Investigation of prolactin-related vasoinhibin in sera from patients with diabetic retinopathy. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 161, 345–353 (2009).

González, C. et al. Elevated vasoinhibins may contribute to endothelial cell dysfunction and low birth weight in preeclampsia. Lab. Invest. 87, 1009–1017 (2007).

Hilfiker-Kleiner, D. et al. A cathepsin D-cleaved 16 kDa form of prolactin mediates postpartum cardiomyopathy. Cell 128, 589–600 (2007).

Halkein, J. et al. MicroRNA-146a is a therapeutic target and biomarker for peripartum cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 2143–2154 (2013).

Tabruyn, S.P., Nguyen, N.Q., Cornet, A.M., Martial, J.A. & Struman, I. The antiangiogenic factor, 16-kDa human prolactin, induces endothelial cell cycle arrest by acting at both the G0–G1 and the G2-M phases. Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 1932–1942 (2005).

D'Angelo, G. et al. 16K human prolactin inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced activation of Ras in capillary endothelial cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 692–704 (1999).

D'Angelo, G., Struman, I., Martial, J. & Weiner, R.I. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in capillary endothelial cells is inhibited by the antiangiogenic factor 16-kDa N-terminal fragment of prolactin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 6374–6378 (1995).

Tabruyn, S.P. et al. The antiangiogenic factor 16K human prolactin induces caspase-dependent apoptosis by a mechanism that requires activation of nuclear factor-κB. Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 1815–1823 (2003).

Clapp, C. & Weiner, R.I. A specific, high affinity, saturable binding site for the 16-kilodalton fragment of prolactin on capillary endothelial cells. Endocrinology 130, 1380–1386 (1992).

Rijken, D.C., Wijngaards, G. & Welbergen, J. Immunological characterization of plasminogen activator activities in human tissues and body fluids. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 97, 477–486 (1981).

Eitzman, D.T., Krauss, J.C., Shen, T., Cui, J. & Ginsburg Lack of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 effect in a transgenic mouse model of metastatic melanoma. Blood 87, 4718–4722 (1996).

Carmeliet, P. et al. Inhibitory role of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in arterial wound healing and neointima formation: a gene targeting and gene transfer study in mice. Circulation 96, 3180–3191 (1997).

Bajou, K. et al. Absence of host plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 prevents cancer invasion and vascularization. Nat. Med. 4, 923–928 (1998).

Bajou, K. et al. The plasminogen activator inhibitor PAI-1 controls in vivo tumor vascularization by interaction with proteases, not vitronectin. Implications for antiangiogenic strategies. J. Cell Biol. 152, 777–784 (2001).

Bajou, K. et al. Host-derived plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) concentration is critical for in vivo tumoral angiogenesis and growth. Oncogene 23, 6986–6990 (2004).

Gerhardt, H. et al. VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J. Cell Biol. 161, 1163–1177 (2003).

McMahon, G.A. et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 regulates tumor growth and angiogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 33964–33968 (2001).

Binder, B.R., Mihaly, J. & Prager, G.W. uPAR-uPA-PAI-1 interactions and signaling: a vascular biologist's view. Thromb. Haemost. 97, 336–342 (2007).

Conese, M. et al. α-2 Macroglobulin receptor/Ldl receptor-related protein(Lrp)-dependent internalization of the urokinase receptor. J. Cell Biol. 131, 1609–1622 (1995).

Lee, S.H., Kunz, J., Lin, S.H. & Yu-Lee, L.Y. 16-kDa prolactin inhibits endothelial cell migration by down-regulating the Ras-Tiam1-Rac1-Pak1 signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 67, 11045–11053 (2007).

Martini, J.F. et al. The antiangiogenic factor 16K PRL induces programmed cell death in endothelial cells by caspase activation. Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 1536–1549 (2000).

Declerck, P.J. et al. Purification and characterization of a plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 binding protein from human plasma. Identification as a multimeric form of S protein (vitronectin). J. Biol. Chem. 263, 15454–15461 (1988).

Seiffert, D. & Loskutoff, D.J. Evidence that type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor binds to the somatomedin B domain of vitronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 2824–2830 (1991).

Mutch, N.J., Thomas, L., Moore, N.R., Lisiak, K.M. & Booth, N.A. TAFIa, PAI-1 and α-antiplasmin: complementary roles in regulating lysis of thrombi and plasma clots. J. Thromb. Haemost. 5, 812–817 (2007).

Zhu, Y., Carmeliet, P. & Fay, W.P. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is a major determinant of arterial thrombolysis resistance. Circulation 99, 3050–3055 (1999).

Shu, E., Matsuno, H., Ishisaki, A., Kitajima, Y. & Kozawa, O. Lack of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 enhances the preventive effect of DX-9065a, a selective factor Xa inhibitor, on venous thrombus and acute pulmonary embolism in mice. Pathophysiol. Haemost. Thromb. 33, 206–213 (2003).

Blasi, F. Urokinase and urokinase receptor: a paracrine/autocrine system regulating cell migration and invasiveness. Bioessays 15, 105–111 (1993).

Prager, G.W. et al. Urokinase mediates endothelial cell survival via induction of the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein. Blood 113, 1383–1390 (2009).

LaRusch, G.A. et al. Factor XII stimulates ERK1/2 and Akt through uPAR, integrins, and the EGFR to initiate angiogenesis. Blood 115, 5111–5120 (2010).

Smith, L.H. et al. Pivotal role of PAI-1 in a murine model of hepatic vein thrombosis. Blood 107, 132–134 (2006).

Tsantes, A.E. et al. The effect of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 4G/5G polymorphism on the thrombotic risk. Thromb. Res. 122, 736–742 (2008).

Nalluri, S.R., Chu, D., Keresztes, R., Zhu, X. & Wu, S. Risk of venous thromboembolism with the angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 300, 2277–2285 (2008).

Scappaticci, F.A. et al. Arterial thromboembolic events in patients with metastatic carcinoma treated with chemotherapy and bevacizumab. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 99, 1232–1239 (2007).

Zangari, M. et al. Thrombotic events in patients with cancer receiving antiangiogenesis agents. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 4865–4873 (2009).

Nar, H. et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1. Structure of the native serpin, comparison to its other conformers and implications for serpin inactivation. J. Mol. Biol. 297, 683–695 (2000).

Gils, A., Knockaert, I. & Declerck, P.J. Substrate behavior of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is not associated with a lack of insertion of the reactive site loop. Biochemistry 35, 7474–7481 (1996).

Thijssen, V.L. et al. Galectin-1 is essential in tumor angiogenesis and is a target for antiangiogenesis therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 15975–15980 (2006).

Jaffe, E.A., Nachman, R.L., Becker, C.G. & Minick, C.R. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J. Clin. Invest. 52, 2745–2756 (1973).

Fusenig, N.E., Amer, S.M., Boukamp, P. & Worst, P.K. Characteristics of chemically transformed mouse epidermal cells in vitro and in vivo. Bull. Cancer 65, 271–279 (1978).

Livak, K.J. & Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 − Δ Δ C t ) Method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Sabatel, C. et al. MicroRNA-21 exhibits antiangiogenic function by targeting RhoB expression in endothelial cells. PLoS ONE 6, e16979 (2011).

Ngo, T.H., Debrock, S. & Declerck, P.J. Identification of functional synergism between monoclonal antibodies. Application to the enhancement of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 neutralizing effects. FEBS Lett. 416, 373–376 (1997).

Carmeliet, P. et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene-deficient mice. I. Generation by homologous recombination and characterization. J. Clin. Invest. 92, 2746–2755 (1993).

Bajou, K. et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 protects endothelial cells from FasL-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Cell 14, 324–334 (2008).

Carmeliet, P. et al. Physiological consequences of loss of plasminogen activator gene function in mice. Nature 368, 419–424 (1994).

Passaniti, A. et al. A simple, quantitative method for assessing angiogenesis and antiangiogenic agents using reconstituted basement membrane, heparin, and fibroblast growth factor. Lab. Invest. 67, 519–528 (1992).

Vercauteren, E. et al. Evaluation of the profibrinolytic properties of an anti-TAFI monoclonal antibody in a mouse thromboembolism model. Blood 117, 4615–4622 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank J.-M. Foidart for helpful discussions. We also thank A. Igout, O. Jacquin and M. Galleni for assisting with SPR, E. Rozet for helping with statistical analysis, R. Lijnen (Center for Molecular and Vascular Biology) for providing the PAI-1 ELISA and N. Fusenig (German Cancer Research) for providing BD VII cells. We thank the technology platforms support staff at the GIGA Research Center and P. Drion of the mouse facility (GIGA). This study was supported by the University of Liège, the Fonds pour la Recherche Industrielle et Agricole (FRIA), Belgium, the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS), Belgium, the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office grant IUAP06/30 (to I.S., A.N. and P.C.), Neoangio program grant no. 616476 from the 'Service Public de Wallonie' (to I.S. and A.N.), the Belgian Foundation against Cancer, Televie, the Léon Frédéricq Fund and the Centre Anticancéreux (Liège, Belgium) and Dutch Cancer Society grants UM2008-4101 and VU2009-4358 (to V.L.T. and A.W.G.). The work of P.C. is supported by the Belgian Science Policy (IAP no. P7/03), the Leducq Network of Excellence, the Flanders Research Foundation (FWO), the Foundation against Cancer, European Research Council Advanced Research Grant EU-ERC269073 and long-term structural Methusalem funding by the Flemish Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.B. and S.H. designed, supervised and conducted the experiments, performed in vitro and in vivo studies and statistical analyses, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. K.B. performed tumor studies, Matrigel plug assays and pulmonary embolism and in vitro studies. S.H., N.-Q.-N.N. and O.N. performed arterial thrombolysis experiments. S.H., S.T., O.N. and S.V. performed retinal angiogenesis experiments. V.L.T. and A.W.G. participated in designing the yeast two-hybrid experiments and in data interpretation. S.D. performed the SPR studies. J.-Y.C. participated in in vitro and in vivo studies. C.P. and M.L. participated in in vitro studies. M.S. performed immunohistochemistry staining and analysis. A.N. participated in data analysis, provided scientific suggestions and contributed to the manuscript review. A.G. and P.J.D. performed the SPR analyses and participated in experiments on PAI-1 antiproteolytic activities. A.B., I.C. and S.V. contributed to in vivo experiment analysis and setup. J.A.M. conceived the study and revised the manuscript. M.D. and P.C. contributed to the experimental analysis and setup and participated in writing the manuscript. I.S. conceived and designed the study, performed yeast-two-hybrid screening, coordinated the experiments and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–7 and Supplementary Table 1 (PDF 1875 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bajou, K., Herkenne, S., Thijssen, V. et al. PAI-1 mediates the antiangiogenic and profibrinolytic effects of 16K prolactin. Nat Med 20, 741–747 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3552

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3552

This article is cited by

-

Pathophysiology and risk factors of peripartum cardiomyopathy

Nature Reviews Cardiology (2022)

-

The HGR motif is the antiangiogenic determinant of vasoinhibin: implications for a therapeutic orally active oligopeptide

Angiogenesis (2022)

-

Anti-angiogenic agents — overcoming tumour endothelial cell anergy and improving immunotherapy outcomes

Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology (2021)

-

Inhibition of cardiac PERK signaling promotes peripartum cardiac dysfunction

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

COVID-19 is a systemic vascular hemopathy: insight for mechanistic and clinical aspects

Angiogenesis (2021)