Abstract

In telomerase-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae, telomeres are maintained by recombination. Here we used a S. cerevisiae assay for characterizing gross chromosomal rearrangements (GCRs) to analyze genome instability in post-senescent telomerase-deficient cells. Telomerase-deficient tlc1 and est2 mutants did not have increased GCR rates, but their telomeres could be joined to other DNAs resulting in chromosome fusions. Inactivation of Tel1 or either the Rad51 or Rad59 recombination pathways in telomerase-deficient cells increased the GCR rate, even though telomeres were maintained. The GCRs were translocations and chromosome fusions formed by nonhomologous end joining. We observed chromosome fusions only in mutant strains expressing Rad51 and Rad55 or when Tel1 was inactivated. In contrast, inactivation of Mec1 resulted in more inversion translocations such as the isochromosomes seen in human tumors. These inversion translocations seemed to be formed by recombination after replication of broken chromosomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Telomeres function in replication and maintenance of chromosome ends, to prevent DNA ends from being inappropriately joined to each other and to prevent chromosome ends from activating checkpoints1,2. Telomeres are maintained by telomerase, which consists of the Est2 catalytic subunit, the Tlc1 RNA and other subunits2. Telomere maintenance also requires other proteins. These include the Tel1 protein kinase that functions in telomere protection and length regulation and proteins such as Cdc13 and Ku that target telomerase to telomeres and protect telomeres from degradation2. Proteins such as Pif1 help regulate telomere length3 and prevent telomerase from adding telomeres to broken DNAs3,4. In telomerase-deficient S. cerevisiae cells telomeres are maintained by recombination5,6. Most mammalian cells lack telomerase7 and have a limited lifespan. Immortalization and cancer progression require increased telomere maintenance capacity, either through upregulation of telomerase activity7 or through the alternative lengthening of telomere pathway8.

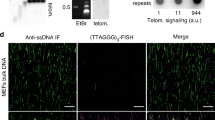

When telomerase-deficient cells senesce, survivors emerge in which telomeres are added by recombination5. When only the Rad51-dependent (requires Rad52, Rad54, Rdh54, Rad55, Rad57) recombination pathway is active, telomeres are characterized by short TG1–3 repeats (type I telomeres), whereas when only the Rad59-dependent (requires Rad52, Rdh54, Rad50, Mre11, Xrs2) recombination pathway is active, telomeres are characterized by long TG1–3 repeats (type II telomeres; refs. 6,9; Supplementary Table 1 online). We examined the effect of tlc1 and est2 mutations and telomere type on the accumulation of GCRs using an assay that detects GCRs that target the left arm of chromosome V (refs. 3,10). Pre-senescent tlc1 and est2 mutants did not have higher GCR rates4, and neither did post-senescent tlc1 survivors having only type I or only type II telomeres (Table 1). In type I and type II tlc1 mutants, the GCRs were a mixture of translocations and chromosome fusions (Tables 2 and 3, Figs. 1 and 2 and Supplementary Table 2 online). This suggests that although recombination allows telomerase-deficient cells to proliferate, recombination-mediated telomere maintenance in tlc1 type I and type II survivors cannot completely compete with telomere end-joining reactions. We observed no chromosome fusions in wild-type cells, in which most GCRs are due to de novo telomere addition (Table 2)10,11, indicating that telomerase more effectively competes with telomere end-joining reactions.

The DNA sequence of all rearrangement breakpoints characterized is available in Supplementary Tables 1–3 online. The underlined portion of the upper DNA sequence is the sequence of chromosome V followed by the standard SGD nucleotide coordinates for the last recognizable nucleotide of chromosome V at the breakpoint. The underlined portion of the lower sequence is the DNA sequence found at the breakpoint followed by the standard SGD nucleotide coordinates for the first nucleotide for the corresponding indicated chromosome. The nucleotides in bold are identical.

Number of events observed in the indicated genetic backgrounds is shown. Bars represent the number of chromosome fusions (upper panel) and translocations (lower panel) observed. The number above each bar in the translocation panel indicates the percentage of the observed translocations that were dicentric, based on the orientation of the DNA sequence at the breakpoint. In this study, all dicentric translocations were nonreciprocal and were associated with the presence of an apparently intact copy of the non–chromosome V target chromosome. This would limit any lethality resulting from subsequent rounds of breakage of dicentric chromosomes. Strains with apparent dicentric chromosomes or chromosome fusions did not show any obvious growth defects.

Deletion of RAD51, RAD55, RAD54, RAD59 or RDH54 caused a small increase in the GCR rate4, and combining these mutations with a tlc1 mutation caused a synergistic increase in the GCR rate in post-senescent cells (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3 online). We did not examine rad52 mutations because they are lethal in combination with telomerase defects5. The GCR rates in rad51 tlc1, rad55 tlc1, rad54 tlc1, rad59 tlc1 and rdh54 tlc1 double mutants were not different (P > 0.10). We observed similar results with mutations in EST2 (Table 1). This suggests that when maintenance of telomeres is partially compromised by inactivation of only one recombination pathway, increased GCRs result even though telomeres are still maintained by recombination.

We determined the breakpoint sequences of GCRs from each strain (Figs. 1 and 2 and Table 2) and the rate of formation of each type of GCR (Table 3). In the double mutants, each class of rearrangement, except as discussed below, was formed at a higher rate than in either wild-type or tlc1 type I and type II strains (P < 0.0007; Table 3). We observed no telomere addition GCRs because their formation requires telomerase4. The GCRs in rad54 tlc1, rad59 tlc1 and rdh54 tlc1 double mutants were translocations, deletions and chromosome fusions. In contrast, rad51 tlc1 and rad55 tlc1 resulted in an increased translocation and deletion rate with little or no effect on the chromosome fusion rate (Table 3). We observed no chromosome fusions in the rad55 tlc1 mutant, and the chromosome fusion rate in the rad51 tlc1 mutant was lower than those in rad54 tlc1, rad59 tlc1 and rdh54 tlc1 double mutants (P = 0.003, P = 0.0003 and P = 0.03, respectively). The breakpoints were predominantly (except in the rad54 tlc1 mutant) at regions of microhomology, although we observed some nonhomology breakpoints (Table 2 and Fig. 1). In most cases, the orientation of the breakpoint partners based on analysis of the breakpoint sequences was consistent with the structure of a monocentric translocation chromosome (Fig. 2). These results indicate that GCRs are formed by joining of broken DNAs with each other or with chromosome ends and that homologous recombination proteins may function at chromosome ends to prevent or promote the participation of telomeres in chromosome fusions.

When combined with tlc1 or est2 mutations, a tel1 mutation causes a synergistic increase in the GCR rate and high frequencies of translocations and spontaneous4 and double-strand break (DSB)-directed12 chromosome fusions (Tables 1 and 3). A tel1 mutation had no effect on GCR rates in combination with mutations in RAD51, RAD55 or RAD59, and the GCR rates of tel1 rad51 tlc1, tel1 rad55 tlc1 and tel1 rad59 tlc1 triple mutants were not different from the those of rad51 tlc1, rad55 tlc1 and rad59 tlc1 double mutants (P > 0.13; Table 1). The rates of translocations and chromosome fusions were similar in rad59 tlc1, tel1 tlc1 and tel1 rad59 tlc1 strains. The tel1 rad51 tlc1 strain accumulated mostly translocations, but chromosome fusions were formed at a higher rate than in the rad51 tlc1 strain (P = 0.02; Table 3). Because mutations in TEL1 are not known to cause defects in the Rad51 or Rad59 recombination pathways, this suggests that defects in a Tel1-dependent checkpoint function3,11 or telomere-capping function4,12,13 and expression of Rad51 (and Rad55) could both disrupt the protective function that prevents telomeres from being joined to broken DNAs.

Because nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) proteins Ku70, Ku80 and ligase 4 promote translocations3,4, telomere-telomere fusions14,15,16,17,18 and fusion of telomeres to an induced DSB12, we examined the role of ligase 4 in chromosome fusions. When we introduced a lig4 mutation into the rad51 tlc1, rad55 tlc1, rad59 tlc1 and tel1 tlc1 double mutants, the GCR rate was reduced to almost wild-type rates and was indistinguishable from that of the lig4 tlc1 double mutant (P > 0.14; Table 1). We obtained similar results with an est2 mutation. The GCR rate and the rates of chromosome fusions and translocations were greatly reduced when we introduced a lig4 mutation into the tel1 tlc1 mutant (Tables 1 and 3). This indicates that GCRs resulting from combining Tel1 defects or recombination defects with telomerase defects are primarily formed by NHEJ of broken DNAs with each other or with chromosome ends.

Combining a mec1 mutation with tlc1 or est2 mutations did not change the GCR rate relative to that of a mec1 single mutant (Table 1). But the GCR spectrum changed from all telomere additions in a mec1 mutant11 to chromosome fusions, translocations and inversion translocations, a translocation structure we have not previously observed4,10,11, in the mec1 tlc1 double mutant (Fig. 1 and Table 3). Analysis of GCR breakpoints in mec1 tlc1 double mutants detected several (two of nine GCRs) inversion translocations at a region of microhomology; we observed a higher proportion (five of ten GCRs) of these events in a mec1 lig4 tlc1 mutant (Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 1). We also observed inversion translocations at low rates in tlc1 type II, tel1 tlc1 lig4, rad59 tlc1 and rdh54 tlc1 strains. The GCR rates in the mec1 rad51 tlc1 and mec1 rad59 tlc1 mutants was roughly two times lower than that in the mec1 tlc1 mutant (Table 1), although this difference was of borderline significance (P < 0.09). The reduced GCR rate in mec1 rad51 tlc1 and mec1 rad59 tlc1 mutants was mainly the result of a large reduction in inversion translocations; other translocations and chromosome fusions were moderately reduced (Fig. 2 and Table 3). This suggests that inversion translocations are formed by Rad51- or Rad59-dependent recombination. Such translocations are similar to the isochromosomes seen in human tumors.

A model describing how defects in telomere maintenance result in increased GCRs is presented in Figure 3. In the absence of telomerase, the telomeres added by recombination can participate in NHEJ at low rates, because telomere maintenance functions do not completely compete with NHEJ, but this does not increase the GCR rate. In the absence of telomerase and either the Rad51 or Rad59 recombination pathways or Tel1, there are more broken chromosomes that escape repair owing to overburdening of the existing recombination capacity by telomere maintenance, less telomere protection or both, resulting in increased GCR rates even though there is sufficient recombination to maintain telomeres. There are three potential sources of broken chromosomes: replication errors that escape repair3,11, dicentric chromosomes due to telomere-telomere fusion followed by breakage of the dicentric chromosomes1,2,15,19 and degradation of chromosome ends by exonucleases such as Exo1 (ref. 20). The observation of chromosome fusion junctions at subtelomeric regions suggests that chromosome ends are degraded, but this is probably not a major source of 'broken' chromosomes, because this predicts that 100% of translocation breakpoints would be in a dicentric orientation, which is not observed. The subsequent rearrangements are predominantly due to NHEJ; joining of broken DNAs to each other yields translocations and joining of broken DNAs to unprotected telomeres yields chromosome fusions. Finally, in the absence of Mec1-dependent DNA damage checkpoints11,21,22, broken chromosomes seem to replicate and then fuse by Rad51- or Rad59-dependent recombination to yield dicentric inversion translocations. This is in contrast to telomerase-defective mammalian cells, in which chromosome fusions and translocations in cells that escape cell cycle arrest and apoptosis because of a p53 mutation result from a ligase 4–dependent NHEJ reaction17,23.

In the absence of telomerase, the telomeres added by recombination5,6 do not prevent the joining of telomeres to broken DNAs at low rates. In the absence of either of the Rad51 or Rad59 recombination pathways or Tel1, there are either increased levels of broken chromosomes that escape repair, decreased telomere protection, or both such that increased GCRs occur. However, the telomeres may also fail to protect chromosomes from telomere-telomere fusions leading to breakage-fusion-bridge cycles (BFB)1,2,15,19 or exonuclease digestion20. The broken chromosomes are then joined to each other or to telomeres by NHEJ to yield GCRs. Chromosome fusions appear to be suppressed by telomere capping proteins Tel1, Rad59, Rad54 and Rdh54 whereas the recombination proteins Rad51 and Rad55-Rad57 may promote chromosome fusions by possibly disrupting telomere capping. In the absence of Mec1, inversion translocations are formed at high rates. This translocation structure is consistent with a mechanism in which broken chromosomes replicate and then fuse in inverted orientation at the broken ends by Rad51- or Rad59-dependent recombination. mec1 mutants also have a defect in Rad55 phosphorylation and reduced homologous recombination21,30 either of which might alter the balance between the types of recombination events available to broken chromosomes. Blue indicates chromosome V, red indicates any other chromosome. The arrowheads indicate telomeres (or sub-telomeric regions), the filled circles indicate centromeres and VR indicates the right arm of chromosome V.

The data presented here illustrate the complex nature of the mechanisms that suppress and promote genome rearrangements. When we combined a telomerase defect with mutations in TEL1, RAD59, RAD54 or RDH54, we observed high levels of chromosome fusions, whereas when we combined telomerase defects with mutations in RAD51 or RAD55, we observed significantly lower chromosome fusion rates. This suggests not only that recombination suppresses chromosome fusions by maintaining telomeres and repairing broken chromosomes but also that assembly of Rad51 on chromosome ends in the presence of Rad55-Rad57 during recombination may disrupt end-protection, facilitating NHEJ when telomere maintenance is partially compromised. In contrast, proteins such as Tel1 seem to help maintain chromosome ends by mediating checkpoint activation3,11 and telomere capping4,12, precluding participation of telomeres in NHEJ. The interaction of a mec1 mutation with telomerase defects uses a different mechanism. Checkpoint defects3 allow broken DNAs to replicate, which allows other rearrangement mechanisms to lead to inversion translocations (under these conditions, there is no further increase in damaged chromosomes, but rather the damaged chromosomes are channeled into a different outcome). These and other studies describing de novo telomere addition GCRs4,10,24, telomere-telomere14,15,17,19,23,25 and fusions of telomeres to spontaneous4 and induced DSBs12,13 (and potentially unstable dicentric chromosomes as well as circular chromosomes14) illustrate the diversity of ways in which telomere or telomerase dysfunction results in genome rearrangements. This raises the possibility that suppression of telomerase activity observed in human genetic diseases26,27,28 and the increased telomere maintenance capacity seen in cancer cells due to upregulation of telomerase7 or activation of the alternative lengthening of telomere pathway8 could each contribute to genome instability.

Methods

Yeast strains.

We disrupted genes of interest in the isogenic strains RDKY3615 (MATa, ura3-52, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, his3Δ200, lys2ΔBgl, hom3-10, ade2Δ1, ade8, hxt13:URA3) and RDKY5027 (MATα, ura3-52, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, his3Δ200, lys2ΔBgl, hom3-10, ade2Δ1, ade8, hxt13:URA3) using standard PCR-based methods. We crossed these strains to generate the series of isogenic MATa strains that we used in the studies described here. We selected the tlc1 or est2 mutant derivatives and subcultured them in liquid media or restreaked them on plates until post-senescence survivors emerged. We then genotyped the survivors by PCR and determined the survivor type by Southern blotting of XhoI-digested genomic DNA with a poly(C1–3A /TG1–3) probe. All the post-senescence strains used contained type II telomeres, except for rad59 tlc1, rad59 lig4 tlc1, rad59 tel1 est2, rad59 tlc1, mre11 tlc1, mre11 lig4 tlc1 and mre11 est2 strains, which contained type I telomeres. We generated post-senescent tlc1 single mutants both by restreaking on rich media and by liquid subculture to generate type I and type II survivors, respectively6. For a given mutant, survivors obtained independently had similar GCR rates.

The strains used for the experiments were as follows: RDKY3615 wild-type; RDKY3633 mre11:HIS3; RDKY3636 rad51:HIS3; RDKY3652 mre11:KAN lig4:HIS3; RDKY3731 tel1:HIS3; RDKY3735 mec1:HIS3 sml1:KAN; RDKY4423 rad59:TRP1; RDKY4425 rdh54:TRP1; RDKY4473 rad54:HIS3; RDKY5203 rad55::TRP1; RDKY5211 tel1:KAN rad51:HIS3; RDKY5212 tel1:HIS3 rad55:TRP1; RDKY5213 tel1:KAN rad59:TRP1; RDKY5214 rad51:HIS3 tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5215 rad55:HIS3 tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5216 rad54:HIS3 tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5217 rad59:TRP1 tlc1:HIS3; RDKY5218 rdh54:TRP1 tlc1:HIS3; RDKY5219 tel1:KAN rad51:HIS3 tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5220 tel1:KAN rad55:HIS3 tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5221 tel1:KAN rad59:TRP1 tlc1:HIS3; RDKY5222 rad51:TRP1 lig4:KAN tlc1:HIS3; RDKY5223 rad55:HIS3 lig4:KAN tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5224 rad59:TRP1 lig4:KAN tlc1:HIS3; RDKY5225 rad51:HIS3 est2:TRP1; RDKY5226 rad59:TRP1 est2:HIS3; RDKY5227 mre11:KAN lig4:HIS3 tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5228 mre11:KAN tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5229 mre11:HIS3 est2:TRP1; RDKY5232 tlc1:TRP1 (type I); RDKY5233 tlc1:TRP1 (type II); RDKY5234 est2:TRP1; RDKY5236 tel1:HIS3 tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5237 lig4:HIS3 tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5238 tel1:HIS3 lig4:KAN; RDKY5239 tel1:HIS3 lig4:KAN tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5240 te1:;HIS3 lig4:KAN est2:TRP1; RDKY5241 tel1:HIS3 est2:TRP1; RDKY5246 mec1:HIS3 sml1:KAN tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5247 mec1:HIS3 sml1:KAN lig4:Kan tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5303 mec1:TRP1 sml1:KAN rad51:HIS3; RDKY5304 mec1:HIS3 sml1:KAN rad59:KAN; RDKY5305 mec1:HIS3 sml1:KAN rad51:KAN tlc1:TRP1; RDKY5306 mec1:HIS3 sml1:KAN rad59:KAN tlc1:TRP1.

GCR rates.

We determined each GCR rate independently by fluctuation analysis two or more times using either 5 or 15 cultures and report the median value10,11. We evaluated statistical significance using the Mann-Whitney test (see URL). We determined the sequences of independent rearrangement breakpoints and the rates of individual breakpoint classes as described10,11. We compared the sequences on both sides of each breakpoint with the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) to identify the fused chromosome partners and to determine the predicted orientation of each chromosome relative to the centromere or telomere.

Translocations consist of a broken chromosome V joined to a fragment of another chromosome or, in some cases, another fragment of chromosome V. We scored all chromosome V sequences fused to telomeric repeats poly(C1–3A/TG1–3) and chromosome V sequences fused to subtelomeric sequences oriented towards the centromere of the target chromosome as chromosome fusions. Inversion translocations are dicentric chromosome V–chromosome V translocations in which a centromere-containing fragment of chromosome V is fused to a virtually identical centromere-containing fragment of chromosome V in inverted orientation at a region of microhomology on the left arm of the broken chromosomes V. For translocations, when the target chromosome arm was predicted to contain a centromere, we classified the translocation as dicentric, and when the target chromosome arm was predicted not to contain a centromere, we classified it as monocentric (the chromosome V fragment that results when the left arm of chromosome V is deleted is always predicted to contain a centromere in the assay used here). We did not confirm these classifications using other methods. Translocations were found by PCR to be nonreciprocal, as previously described10; the presence of an intact target chromosome suggests that the translocations observed do not cause a disadvantage to the cell.

URL.

The programs we used for the Mann-Whitney statistical test are available at http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/vshome.html

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Genetics website.

References

Blackburn, E.H. Telomere states and cell fates. Nature 408, 53–56 (2000).

Cervantes, R.B. & Lundblad, V. Mechanisms of chromosome-end protection. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 351–356 (2002).

Kolodner, R.D., Putnam, C.D. & Myung, K. Maintenance of genome stability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 297, 552–557 (2002).

Myung, K., Chen, C. & Kolodner, R.D. Multiple pathways cooperate in the suppression of genome instability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 411, 1073–1076 (2001).

Lundblad, V. & Blackburn, E.H. An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est1- senescence. Cell 73, 347–360 (1993).

Teng, S.C. & Zakian, V.A. Telomere-telomere recombination is an efficient bypass pathway for telomere maintenance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 8083–8093 (1999).

Kim, N.W. et al. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science 266, 2011–2015 (1994).

Bryan, T.M., Englezou, A., Dalla-Pozza, L., Dunham, M.A. & Reddel, R.R. Evidence for an alternative mechanism for maintaining telomere length in human tumors and tumor-derived cell lines. Nat. Med. 3, 1271–1274 (1997).

Chen, Q., Ijpma, A. & Greider, C.W. Two survivor pathways that allow growth in the absence of telomerase are generated by distinct telomere recombination events. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 1819–1827 (2001).

Chen, C. & Kolodner, R.D. Gross chromosomal rearrangements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae replication and recombination defective mutants. Nat. Genet. 23, 81–85 (1999).

Myung, K., Datta, A. & Kolodner, R.D. Suppression of spontaneous chromosomal rearrangements by S phase checkpoint functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 104, 397–408 (2001).

Chan, S.W. & Blackburn, E.H. Telomerase and ATM/Tel1p protect telomeres from nonhomologous end joining. Mol. Cell 11, 1379–1387 (2003).

DuBois, M.L., Haimberger, Z.W., McIntosh, M.W. & Gottschling, D.E. A quantitative assay for telomere protection in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 161, 995–1013 (2002).

Liti, G. & Louis, E.J. NEJ1 prevents NHEJ-dependent telomere fusions in yeast without telomerase. Mol. Cell 11, 1373–1378 (2003).

Mieczkowiski, P., Mieczkowska, J., Dominska, M. & Petes, T.D. Genetic regulation of telomere-telomere fusions in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 10854–10859 (2003).

Ferreira, M.G. & Cooper, J.P. The fission yeast Taz1 protein protects chromosomes from Ku-dependent end-to-end fusions. Mol. Cell 7, 55–63 (2001).

Smogorzewska, A., Karlseder, J., Holtgreve-Grez, H., Jauch, A. & de Lange, T. DNA ligase IV-dependent NHEJ of deprotected mammalian telomeres in G1 and G2. Curr. Biol. 12, 1635–1644 (2002).

Espejel, S. et al. Mammalian Ku86 mediates chromosomal fusions and apoptosis caused by critically short telomeres. EMBO J. 21, 2207–2219 (2002).

Hackett, J.A., Feldser, D.M. & Greider, C.W. Telomere dysfunction increases mutation rate and genomic instability. Cell 106, 275–286 (2001).

Maringele, L. & Lydall, D. EXO1-dependent single-stranded DNA at telomeres activates subsets of DNA damage and spindle checkpoint pathways in budding yeast yku70Delta mutants. Genes Dev. 16, 1919–1933 (2002).

Weinert, T.A., Kiser, G.L. & Hartwell, L.H. Mitotic checkpoint genes in budding yeast and the dependence of mitosis on DNA replication and repair. Genes Dev. 8, 652–665 (1994).

Cha, R.S. & Kleckner, N. ATR homolog Mec1 promotes fork progression, thus averting breaks in replication slow zones. Science 297, 602–606 (2002).

Artandi, S.E. et al. Telomere dysfunction promotes non-reciprocal translocations and epithelial cancers in mice. Nature 406, 641–645 (2000).

Fouladi, B., Sabatier, L., Miller, D., Pottier, G. & Murnane, J.P. The relationship between spontaneous telomere loss and chromosome instability in a human tumor cell line. Neoplasia 2, 540–554 (2000).

Hande, M.P., Samper, E., Lansdorp, P. & Blasco, M.A. Telomere length dynamics and chromosomal instability in cells derived from telomerase null mice. J. Cell Biol. 144, 589–601 (1999).

Vulliamy, T. et al. The RNA component of telomerase is mutated in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Nature 413, 432–435 (2001).

Mitchell, J.R., Wood, E. & Collins, K.A telomerase component is defective in the human disease dyskeratosis congenita. Nature 402, 551–555 (1999).

Zhang, A. et al. Deletion of the telomerase reverse transcriptase gene and haploinsufficiency of telomere maintenance in Cri du chat syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 940–948 (2003).

Symington, L.S. Role of RAD52 epistasis group genes in homologous recombination and double-strand break repair. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66, 630–670 (2002).

Bashkirov, V.I., King, J.S., Bashkirova, E.V., Schmuckli-Maurer, J. & Heyer, W.D. DNA repair protein Rad55 is a terminal substrate of the DNA damage checkpoints. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4393–4404 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Mazur, J. Petrini, C. Putnam and K. Schmidt for comments on the manuscript and J. Weger, D. Cassel, M. Tresierras and S. Ness for DNA sequencing. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant to R.D.K.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pennaneach, V., Kolodner, R. Recombination and the Tel1 and Mec1 checkpoints differentially effect genome rearrangements driven by telomere dysfunction in yeast. Nat Genet 36, 612–617 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1359

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1359

This article is cited by

-

Signification and Application of Mutator and Antimutator Phenotype-Induced Genetic Variations in Evolutionary Adaptation and Cancer Therapeutics

Journal of Microbiology (2023)

-

Evolutionary engineering and molecular characterization of a caffeine-resistant Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology (2019)

-

Inositol polyphosphates: a new frontier for regulating gene expression

Chromosoma (2008)

-

Mutation in Rpa1 results in defective DNA double-strand break repair, chromosomal instability and cancer in mice

Nature Genetics (2005)