Abstract

Distal hereditary motor neuropathies are pure motor disorders of the peripheral nervous system resulting in severe atrophy and wasting of distal limb muscles1. In two pedigrees with distal hereditary motor neuropathy type II linked to chromosome 12q24.3, we identified the same mutation (K141N) in small heat-shock 22-kDa protein 8 (encoded by HSPB8; also called HSP22). We found a second mutation (K141E) in two smaller families. Both mutations target the same amino acid, which is essential to the structural and functional integrity of the small heat-shock protein αA-crystallin2. This positively charged residue, when mutated in other small heat-shock proteins, results in various human disorders3,4. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments showed greater binding of both HSPB8 mutants to the interacting partner HSPB1. Expression of mutant HSPB8 in cultured cells promoted formation of intracellular aggregates. Our findings provide further evidence that mutations in heat-shock proteins have an important role in neurodegenerative disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Distal hereditary motor neuropathy (HMN; OMIM 158590) is genetically heterogeneous and has been associated with eight loci and three genes so far5,6,7. We previously mapped autosomal dominant distal HMN type II to a 5-Mb candidate region at 12q24.3 in a Belgian family8,9. Distal HMN type II is an exclusive lower motor neuron disease without sensory loss, with an onset age of 15–25 years. The presenting symptoms are paresis of the extensor muscles of the big toe and later of the extensor muscles of the feet. The disease progresses rapidly, and complete paralysis of all distal muscles of the lower extremities occurs within 5 years. Affected individuals have chronic neurogenic alterations in electromyography10.

Here, we identified a large Czech family with 34 affected individuals (Supplementary Fig. 1 online) with a phenotype markedly similar to that of the previously reported Belgian family with distal HMN type II. In both families, we did a haplotype analysis using short tandem repeat (STR) markers and identified several recombinants, narrowing the candidate region from 5 Mb (ref. 8) to 1.7 Mb between D12S349 and PLA2G1B (Supplementary Fig. 2 online). This refined region contains 9 known and 14 predicted genes, of which 5 known genes have previously been excluded11,12. We selected four of the other genes for mutation analysis: PRKAB1 (protein kinase, AMP-activated beta 1), CIT (citron; rho-interacting, serine-threonine kinase), SIRT4 (sirtuin 4) and HSPB8 (heat shock 22-kDa protein 8, also called HSP22, H11 and E2IG1). We sequenced all known exons and intron-exon boundaries of each of these genes. In the Belgian and Czech families, we identified a heterozygous transversion, 423G→C, in exon 2 of HSPB8 (resulting in the amino acid substitution K141N; Fig. 1a,b). In two other families (Bulgarian and English) with distal HMN, we found a heterozygous transition, 421A→G, involving the same lysine residue (amino acid substitution K141E; Fig. 1a,b). Both missense mutations cosegregated perfectly with the distal HMN type II phenotype in all families (Supplementary Fig. 1 online), and both were absent in 400 Caucasian control chromosomes. Because the Belgian and Czech families and the Bulgarian and English families shared the mutations K141N and K141E, respectively, we carried out haplotype analysis with 11 STR markers and four intragenic HSPB8 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The results suggest that the families are genetically not closely related (Supplementary Fig. 2 online).

(a) Electropherogram showing the 421A→G and 423G→C sequence variations in HSPB8 exon 2, resulting in the K141E and K141N missense mutations in families AJ-12 and CMT-355 and families CMT-M and CMT-196, respectively. The corresponding genomic sequence of a control person is shown in the middle. (b) HSPB8 spans ∼16 kb and contains three exons. The α-crystallin domain is indicated in red. (c) ClustalW multiple protein alignment of HSPB8 orthologs. The protein sequences show the central α-crystallin domain (Hs.HSPB8 protein fragment 120–145) surrounding the K141E and K141N mutations. Orthologs in Homo sapiens (Hs), Mus musculus, Rattus norvegicus, Drosophila melanogaster, Mycobacterium leprae, Caenorhabditis elegans and Triticum aestivum are shown. The putative N-myristoylation site is boxed in green; the N-glycosylation and protein kinase C motifs are boxed in blue. Both mutations are indicated by an arrow.

HSPB8 belongs to the superfamily of mammalian small heat-shock proteins or stress proteins13,14,15,16. Members of this superfamily share a conserved α-crystallin domain in their C-terminal part and the WDPF motif in their N-terminal part, whereas other parts of the sequence (N-terminal halves and extreme C-terminal tails) are more variable17,18. The missense mutations K141N and K141E are located in the central α-crystallin domain of HSPB8. Alignment of HSPB8 orthologs showed that the targeted lysine residue is highly conserved in the α-crystallin domain (Fig. 1c). This positively charged amino acid is essential for the structural and functional integrity of αA-crystallin2. We confirmed the HSPB8 expression profile as reported in the UniGene Database (Hs.111676 and Mm.21549) and in ref. 19 (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). In the nervous system, we detected high expression in spinal cord, specifically in motor and sensory neurons (Supplementary Fig. 3 online).

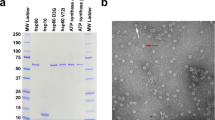

HSPB8 is a phosphoprotein that interacts with HSPB1 and might be involved in the modulation of HSPB1 activities13,19. We investigated the effect of the K141N and K141E mutations of HSPB8 on its interaction with HSPB1 by coimmunoprecipitation. We transiently expressed enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-tagged wild-type and mutant HSPB8 in simian fibroblasts (COS) and human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293T). We immunoprecipitated fusion proteins using a polyclonal antibody to EGFP and analyzed immunoprecipitates for the presence of HSPB1 by western blotting. In COS cells, endogenous HSPB1 coimmunoprecipitated with wild-type HSPB8 (Fig. 2a). Conversely, immunoprecipitation of EGFP-tagged HSPB1 pulled down endogenous wild-type HSPB8 from COS or human neuronal (SHSY5Y) cells (Fig. 2c). Immunoprecipitation of the HSPB8 mutants from COS lysates also showed association with endogenous HSPB1 (Fig. 2a), indicating that the missense mutations do not abolish interaction between HSPB8 and HSPB1.

(a–c) Expression of mutant HSPB8 does not disrupt interaction with HSPB1. (a) COS cells were transiently transfected with EGFP-tagged wild-type or mutant HSPB8, immunoprecipitated and analyzed for the presence of HSPB1 by immunoblotting with a monoclonal antibody. A stronger HSPB1 signal was observed for HSPB8-K141N (lane 4) and HSPB8-K141E (lane 5) than for wild-type HSPB8 (lane 2). Lane 1 (pEGFP-C1) and lane 3 (untransfected cell) represent controls. (b) The same experiment was done using HEK293T cells cotransfected with pcDNA3.1-HSPB1. HEK293T cells do not express HSPB1. Lane 1, pEGFP-C1 and pcDNA3.1; lane 2, HSPB8- pEGFP-C1 and HSPB1-pcDNA3.1; lane 3, untransfected cells; lane 4, K141N-pEGFP-C1 and HSPB1-pcDNA3.1; lane 5, K141E-pEGFP-C1 and HSPB1-pcDNA3.1. Ectopically expressed HSPB1 was coimmunoprecipitated to the same extent by wild-type and mutant HSPB8 as endogenous HSPB1 in COS cells. (c) COS (lane 1) or SHSY5Y (lane 2) cells were transfected with HSPB1-pEGFP-C1, immunoprecipitated and analyzed for the presence of HSPB8 with a specific antibody. Normalization data is shown in lower panels (a–c). (d) Densitometric quantification of the immunoprecipitation experiments shown in a–c. The amount of HSPB1 coprecipitating with EGFP-tagged mutant HSPB8 (K141N and K141E) is shown for HEK293T and COS cells (normalized ratio in cells transfected with wild-type HSPB8 taken as 1). The data for the HEK293T and COS cells are the averages of three independent experiments. Normalization data is shown in lower panels of a–c. (e) Immunoblot showing expression of HSPB1 in COS cells and absence of expression in HEK293T cells. Cytosolic proteins in lanes 1–5 correspond with lane numbers in a and b. Proteins were detected with monoclonal antibody to HSPB1. (f) Western blot on lysates obtained from transfected HEK293T cells and probed with antibody (Ab) to HSPB1, showing equal expression levels of HSPB1. The blot was then reprobed with antibody to tubulin to show equal loading.

Both HSPB8 mutants pulled down more HSPB1 protein than wild-type HSPB8 did. We quantified the immunoprecipitation data from three independent experiments by enhanced chemiluminescence detection densitometry (Fig. 2d). To verify the specificity of the interaction between HSPB8 and HSPB1, we cotransfected HEK293T cells that do not express HSPB1 (Fig. 2e) with EGFP-HSPB8 (wild-type or mutant) and HSPB1 carrying V5 and His6 epitope tags. The results were identical to those obtained with COS cells: both wild-type and mutant HSPB8 interacted with HSPB1, and both mutants pulled down more HSPB1 than wild-type HSPB8 did (Fig. 2b,d). These differences were not due to varying expression levels of HSPB8 or HSPB1. Western blots with antibodies to HSPB8 and HSPB1 showed equal expression levels of EGFP-tagged wild-type and mutant HSPB8 and HSPB1 in both COS and HEK293T cells (Fig. 2a,b,f). Rabbit and mouse IgGs did not immunoprecipitate the HSPB8-HSPB1 complex (data not shown).

The residue Lys141 in HSPB8 that is mutated in families with distal HMN type II corresponds to the residue Arg120 that is mutated in αB-crystallin, causing a familial desmin-related myopathy (DRM; OMIM 601419; ref. 3). In DRM, intracellular desmin aggregates form in cells with the R120G mutation20. To test whether K141N or K141E mutant HSPB8 could also lead to the formation of aggregates, we carried out immunofluorescence experiments in transfected COS cells (Fig. 3). After 48 h in COS cells, EGFP-tagged wild-type HSPB8 showed a homogeneous distribution throughout the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 3a). In contrast, the mutant forms led to cytoplasmic or perinuclear HSPB8-labeled aggregates (Fig. 3b,c). The percentage of aggregate-positive cells was significantly higher in cells transfected with K141N HSPB8 (62% ± 2%) or with K141E HSPB8 (59% ± 4%) than in those transfected with wild-type HSPB8 (3% ± 0.3%; P = 1.5 × 10−6 and 2.8 × 10−5, respectively; data are from three independent experiments). Western-blot analysis 48 h after transfection showed similar levels of expression of HSPB8 in COS cells transfected with wild-type and mutant forms of HSPB8 (data not shown). Colocalization studies showed that wild-type HSPB8 and HSPB1 were located in the cytoplasm of COS cells. In cells transfected with HSPB8 mutants, we observed colocalization between HSPB8 aggregates and HSPB1 (Fig. 4). We investigated whether the aggregates reduced cell viability. When transfected into N2a neuronal cells, K141E mutant HSPB8 significantly reduced cell viability, as compared with wild-type HSPB8, measured 48 h after transfection (P = 0.007). K141N mutant HSPB8 also reduced viability, but to a lesser extent (P = 0.043) (Fig. 5).

The cells were processed for immunofluorescence analysis 48 h after transfection with pEGFP-C1 wild-type or mutant HSPB8. White arrows indicate HSPB8 aggregates (b,c), which were absent in cells transfected with wild-type (WT) HSPB8 (a). At least 200 cells were counted in three randomly chosen microscopic fields by two independent investigators. N, nucleus. Scale bars, 30 μm.

COS cells were cotransfected with pEGFP-C1 wild-type or mutant HSPB8 (green) and pcDNA3.1-HSPB1 (red). The cells were processed for immunofluorescence analysis 48 h after transfection and visualized with a laser scanner microscope. (a) Wild-type (WT) HSPB8, wild-type HSPB1 and merged confocal image. (b) K141N mutant HSPB8, wild-type HSPB1 and merged image. (c) K141E mutant HSPB8, wild-type HSPB1 and merged image. Arrows indicate the aggregates.

The relative survival was measured after 48 h. 1, control (empty pEGFP-C1 vector); 2, control (no vector); 3, pEGFP-C1 wild-type HSPB8; 4, pEGFP-C1 HSPB8 K141N; 5, pEGFP-C1 HSPB8 K141E. Data shown are mean ± s.e.m. of five independent experiments. P values: HSPB8 K141N, 0.043; HSPB8 K141E, 0.007. Statistical significance was determined using a Student's t-test.

We showed that mutations in HSPB8 are closely associated with motor neuropathy, specifically distal HMN type II. The missense mutations in the HSPB8 protein do not disrupt interaction with HSPB1, but strengthen it, leading to the formation of aggregates. Missense mutations in other sHSPs, namely αA-crystallin (R116C) and αB-crystallin (R120G) cause an autosomal dominant congenital cataract (OMIM 123580; ref. 4) and DRM3, respectively. Arg116 and Arg120 correspond to Lys141 in HSPB8. The R120G mutation in αB-crystallin associated with DRM causes the formation of large desmin aggregates3,20, and the R116C mutation in αA-crystallin that causes congenital cataract shows a higher affinity for hetero-aggregation with αB-crystallin21. Whether the aggregates of HSPB8 and HSPB1, observed as a short-term result in in vitro studies, also occur during the slow degeneration of motor neurons in individuals with distal HMN type II is an open question that can be addressed only by the generation of animal models carrying the HSPB8 mutations. Some sHSPs have crucial roles in neuronal apoptosis and muscle function3,22. R116C in αA-crystallin diminishes its protective ability against stress-induced lens epithelial cell apoptosis23, and αB-crystallin negatively regulates apoptosis by inhibiting caspase-3 activation24. HSPB2 associates specifically with and activates the myotonic dystrophy protein kinase, which causes myotonic dystrophy (OMIM 160900; ref. 25). Mutation of Arg116 to an acidic residue caused marked changes in protein structure, suggesting that a positive charge must be preserved at this position for the structural and functional integrity of αA-crystallin2. The mutations of HSPB8 at Lys141 have a gain-of-function effect, which may lead to dysfunction of axonal transport and dysregulation of the cytoskeleton, causing motor neuron death in distal HMN. Other important unknown mechanisms may also be involved in the pathogenesis of distal HMN. Notably, transcriptional and post-translational regulation of HSPB1, the molecular partner of HSPB8, is necessary for sensory and motor neuron survival after peripheral nerve injury22. HSPB1 was upregulated in a transgenic model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis26. Our finding that HSPB8 has a pivotal role in the biology of the motor axon suggests that upregulation of HSPB8 is a potential strategy to protect the motor neuron from degeneration.

Methods

Affected individuals.

Our study included four families with distal HMN (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). In the Belgian family (CMT-M), we previously identified the locus on chromosome 12q24.3 linked with distal HMN type II (refs. 8–10). The Czech (CMT-196), English (CMT-355) and Bulgarian (AJ-12) families were recently identified. From affected family members and control persons, we isolated genomic DNA from total blood samples using a standard extraction protocol. Informed consent was obtained from all family members, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Universities of Antwerp, Oxford, Prague and Sofia.

Genotyping and genetic linkage analysis.

We carried out PCR amplification with dye-labeled STR primers on a DYAD thermocycler (MJ Research). We analyzed fragments on an ABI3700 DNA sequencer with the ABI GENESCAN 3.1 and GENOTYPER 2.1 software (Applied Biosystems). For analysis of linkage to HSPB8 and STR markers, we computed two-point lod scores using the MLINK program of the FASTLINK package. We assumed autosomal dominant inheritance, a disease frequency of 1 in 10,000, equal male and female recombination rates and complete penetrance. We calculated lod scores assuming equal allele frequencies for all markers. We established the order of markers on the genetic and physical maps by consulting the Genome Database and the National Center for Biotechnology Information genome database.

Mutation analysis.

We used the National Center for Biotechnology Information Entrez Genome Map Viewer, the Ensembl Human Genome Server and the GenBank database to find known genes, expressed-sequence tags and putative new genes in the region linked with distal HMN type II. We determined the exon-intron boundaries of the candidate sequences by BLAST searches against the high-throughput genome sequences. All exons of the genes PRKAB1, CIT, SIRT4 and HSPB8 were amplified by PCR using intronic primers (sequences available on request). We sequenced PCR products using the DYEnamic ET Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Sequence reactions were loaded on the ABI3700 sequencer (Applied Biosystems). We collected and analyzed data using the ABI DNA sequencing analysis software, version 3.6.

Expression analysis.

We obtained the plasmid clone IRALp962K0712, containing the complete human HSPB8 cDNA sequences, from RZPD (The Resource Center of the German Human Genome Project). We used gene-specific primers to construct a HSPB8 cDNA probe of 800 bp and used this probe to hybridize the Human 12- and 8-lane Multiple Tissue and Brain Northern blot (Clontech).

We extracted total RNA from mouse muscle (Navy Medical Research Institute) using the Totally RNA Kit (Ambion). We carried out RT-PCR using the Random Primer DNA Labeling System (Life Technologies). The full-length mouse HSPB8 cDNA was used as a probe to hybridize the Mouse Multiple Tissues and Embryos Northern blot (Clontech). We also hybridized northern blots with an ACTB cDNA probe (Clontech) as a control for RNA loading.

We isolated ventral horns and dorsal root ganglia from 13-d-old mouse embryos and extracted total RNA using the Totally RNA Kit (Ambion). We carried out RT-PCR using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCT (Invitrogen). We used mouse HSPB8 cDNA primers (sequences available on request) to amplify an HSPB8 cDNA fragment of 687 bp.

cDNA cloning and mutagenesis.

We cloned cDNA encoding full-length wild-type human HSPB8 or HSPB1 (refs. 19,27) as a HindIII fragment into the pEGFP-C1 (Clontech) and pcDNA3.1V5/His6 TOPO (Invitrogen) vectors by PCR using the RZPD plasmids IRALp962K0712 (HSPB8) and IRALp962H201 (HSPB1) as templates. For site-directed mutagenesis of the HSPB8 mutations 423C→G and 421A→G, we used the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). All constructs were verified by direct DNA sequencing.

Immunoprecipitation.

We transfected HEK293T cells with calcium phosphate, COS cells with polyethylenimine and SHY5Y cells with lipofectamine 2000 according to standard procedures using 6–18 μg of DNA construct. After 24 h, we washed cells twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (2.7 mM KCL, 1.47 mM KH2PO4, 137 mM NaCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.4) and lysed them in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 5 mM levamisole, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 8 mm sodium-β-glycerophosphate and a protease inhibitor cocktail mix (Roche Diagnostics). We disrupted cells by sonication and centrifuged the crude extract at 4 °C for 10 min (14,000 r.p.m.). We incubated 1 mg of proteins overnight with affinity-purified antibodies to EGFP and then for 4 h with protein G–Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). We washed the beads five times with lysis buffer, boiled them for 5 min in Laemmli sample buffer and fractionated the proteins by SDS-PAGE followed by western blotting. We visualized proteins by enhanced chemiluminescence detection (ECL kit; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Immunostaining and microscopy.

We viewed the cells directly for EGFP fluorescence after fixing them with 3% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 20 min at room temperature. We examined cells using a Zeiss Axioplan II epifluorescence microscope equipped with a 63× objective. We captured images using a cooled CCD Axiocam Camera and KS100 software (Zeiss).

Miscellaneous.

We affinity-purified antibodies to EGFP according to standard procedures28. We determined protein concentrations by the method of Bradford29 using bovine serum albumin as a standard. We carried out SDS-PAGE according to Matsudaira and Burgess30.

Cell viability test.

We cultured N2a neuroblastoma cells (CCL131; American Type Culture Collection) in a 1:1 mix of Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium and F12 medium with glutamax (Gibco Invitrogen) supplemented with nonessential amino acids, penicillin (100 U ml−1), streptomycin (100 μg ml−1) and 10% fetal calf serum. We transfected cells with 5 μg of mutated or wild-type HSPB8 plasmid DNA using the Nucleofector technology (Amaxa). We collected exponentially growing N2a cells and resuspended them at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells per 100 μl in a cuvette containing Nucleofector solution T. After transfection, we resuspended cells in serum-free medium and plated them in a 96-well plate. Using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter, we determined transfection efficiency after 24 h and 48 h (92% ± 4% and 88% ± 8%, respectively). We determined cell viability 3 h, 24 h and 48 h after transfection using the CellTiter 96 AQueous Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega). Western blots showed mutant and wild-type HSPB8 proteins to be expressed at comparable levels.

URLs.

The FASTLINK package is available at http://www.cs.rice.edu/~schaffer/fastlink.html. The Genome Database is available at http://www.gdb.org/, and the National Center for Biotechnology Information genome database is available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/LocusLink/. The National Center for Biotechnology Information Entrez Genome Map Viewer is available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mapview/map_search.cgi?chr=hum_chr.inf&query/. The Ensembl Human Genome Server is available at http://www.ensembl.org/, and the GenBank database is available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=Nucleotide/. The RZPD is available at http://www.rzpd.de/. ClustalW multiple protein alignment is available at http://npsa-pbil.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=npsa_clustalw.html.

Accession numbers.

GenBank protein sequences: human HSPB8, NP_055180; mouse HSPB8, NP_109629; rat HSPB8, NP_446064; Drosophila melanogaster HSPB8, NP_729477; Caenorhabditis elegans HSPB8, NP_509045; Triticum aestivum (bread wheat) GI 17942916, 1GMEA; Mycobacterium leprae Hsp16.7, P12809. The GenBank genomic sequence NT_009775 includes the genes PRKAB1 (NM_006253), CIT (NM_007174), SIRT4 (NM_012240) and HSPB8 (NM_014365). HSPB8 SNPs in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Entrez SNP database: Rs2278181, Rs2278182, Rs11038 and Rs1133026.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Genetics website.

References

Harding, A.E. & Thomas, P.K. Hereditary distal spinal muscular atrophy. A report on 34 cases and a review of the literature. J. Neurol. Sci. 45, 337–348 (1980).

Bera, S., Thampi, P., Cho, W.J. & Abraham, E.C. A positive charge preservation at position 116 of alpha A-crystallin is critical for its structural and functional integrity. Biochemistry 41, 12421–12426 (2002).

Vicart, P. et al. A missense mutation in the alphaB-crystallin chaperone gene causes a desmin-related myopathy. Nat. Genet. 20, 92–95 (1998).

Litt, M. et al. Autosomal dominant congenital cataract associated with a missense mutation in the human alpha crystallin gene CRYAA. Hum. Mol. Genet. 7, 471–474 (1998).

Grohmann, K. et al. Mutations in the gene encoding immunoglobulin μ-binding protein 2 cause spinal muscular atrophy with respiratory distress type 1. Nat. Genet. 29, 75–77 (2001).

Puls, I. et al. Mutant dynactin in motor neuron disease. Nat. Genet. 33 (4), 455–456 (2003).

Antonellis, A. et al. Glycyl tRNA synthetase mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2D and distal spinal muscular atrophy type V. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 1293–1299 (2003).

Timmerman, V. et al. Distal hereditary motor neuropathy type II (distal HMN II): mapping of a locus to chromosome 12q24. Hum. Mol. Genet. 5, 1065–1069 (1996).

Irobi, J. et al. A clone contig of 12q24.3 encompassing the distal hereditary motor neuropathy type II gene. Genomics 65, 34–43 (2000).

Timmerman, V. et al. Linkage analysis of distal hereditary motor neuropathy type II (distal HMN II) in a single pedigree. J. Neurol. Sci. 109, 41–48 (1992).

Irobi, J. et al. Exclusion of 5 functional candidate genes for distal hereditary motor neuropathy type II (distal HMN II) linked to 12q24.3. Ann. Hum. Genet. 65, 517–529 (2001).

Irobi, J. et al. Mutation analysis of 12 candidate genes for distal hereditary motor neuropathy type II (distal HMN II) linked to 12q24.3. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 7, 87–95 (2002).

Sun, X. et al. Interaction of human HSPB8 (HSPB8) with other small heat shock proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 2394–2402 (2003).

Fontaine, J.M., Rest, J.S., Welsh, M.J. & Benndorf, R. The sperm outer dense fiber protein is the 10th member of the superfamily of mammalian small stress proteins. Cell Stress Chaperones 8, 62–69 (2003).

Kappe, G. et al. The human genome encodes 10 alpha-crystallin-related small heat shock proteins: HspB1-10. Cell Stress Chaperones 8, 53–61 (2003).

Concannon, C.G., Gorman, A.M. & Samali, A. On the role of HSPB1 in regulating apoptosis. Apoptosis 8, 61–70 (2003).

De Jong, W.W., Caspers, G.J. & Leunissen, J.A. Genealogy of the alpha-crystallin-small heat-shock protein superfamily. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 22, 151–162 (1998).

MacRae, T.H. Structure and function of small heat shock/alpha-crystallin proteins: established concepts and emerging ideas. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 57, 899–913 (2000).

Benndorf, R. et al. HSPB8, a new member of the small heat shock protein superfamily, interacts with mimic of phosphorylated HSPB1 ((3D)HSPB1). J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26753–26761 (2001).

Zobel, A.T.C. et al. Distinct chaperone mechanisms can delay the formation of aggresomes by the myopathy-causing R120G alpha B-crystallin mutant. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 1609–1620 (2003).

Bera, S. & Abraham, E.C. The alphaA-crystallin R116C mutant has a higher affinity for forming heteroaggregates with alphaB-crystallin. Biochemistry 41, 297–305 (2002).

Benn, S.C. et al. HSPB1 upregulation and phosphorylation is required for injured sensory and motor neuron survival. Neuron 36, 45–56 (2002).

Andley, U.P., Patel, H.C. & Xi, J.H. The R116C mutation in alpha A-crystallin diminishes its protective ability against stress-induced lens epithelial cell apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 10178–10186 (2002).

Kamradt, M.C., Chen, F., Sam, S. & Cryns, V.L. The small heat shock protein alpha B-crystallin negatively regulates apoptosis during myogenic differentiation by inhibiting caspase-3 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 38731–38736 (2002).

Suzuki, A. et al. MKBP, a novel member of the small heat shock protein family, binds and activates the myotonic dystrophy protein kinase. J. Cell Biol. 140, 1113–1124 (1998).

Vleminckx, V. et al. Upregulation of HSPB1 in a transgenic model of ALS. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 61, 968–974 (2002).

Carper, S.W., Rocheleau, T.A. & Storm, F.K. cDNA sequence of a human heat-shock protein HSPB1. Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 6457 (1990).

Gettemans, J., De Ville, Y., Waelkens, E. & Vandekerckhove, J. The actin-binding properties of the Physarum actin-fragmin complex. Regulation by calcium, phospholipids, and phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2644–2651 (1995).

Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Matsudaira, P.T. & Burgess, D.R. SDS microslab linear gradient polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 87, 386–396 (1978).

Acknowledgements

We thank the affected individuals and families for their cooperation and participation; the VIB Genetic Service Facility (http://www.vibgeneticservicefacility.be/) for genotyping and sequencing; R. Benndorf for the human HSPB8 antibody; J.P. Timmermans for help with confocal microscopy; J. Theuns for discussions; and B. Ishpekova, M. Rédlová, J. Haberlová and M. Bojar for help with EMG and sampling material from affected individuals. This research project was supported by the Special Research Fund of the Universities of Antwerp, Ghent and Leuven, Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders, Medical Foundation Queen Elisabeth, “Fortis Bank Verzekeringen”, Interuniversity Attraction Poles program P5/19 of the Belgian Federal Science Office and “Association Belge contre les Maladies Neuromusculaires”. A.J. received fellowships from the Belgian Federal Science Office and Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders. N.V. and I.D. received PhD fellowships from the Institute of Science and Technology. W.R. is a clinical investigator of the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders Flanders, Belgium. P.S. and R.M. were supported by grants from the Internal Grant Agency of Ministry of Health, Czech Republic. P.S. received a fellowship of the European Neurological Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Irobi, J., Impe, K., Seeman, P. et al. Hot-spot residue in small heat-shock protein 22 causes distal motor neuropathy. Nat Genet 36, 597–601 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1328

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1328

This article is cited by

-

Small heat shock proteins operate as molecular chaperones in the mitochondrial intermembrane space

Nature Cell Biology (2023)

-

Molecular Chaperones as Therapeutic Target: Hallmark of Neurodegenerative Disorders

Molecular Neurobiology (2023)

-

Heat-shock chaperone HSPB1 regulates cytoplasmic TDP-43 phase separation and liquid-to-gel transition

Nature Cell Biology (2022)

-

HSP22 (HSPB8) positively regulates PGF2α-induced synthesis of interleukin-6 and vascular endothelial growth factor in osteoblasts

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2021)

-

A novel deletion in the C-terminal region of HSPB8 in a family with rimmed vacuolar myopathy

Journal of Human Genetics (2021)