Abstract

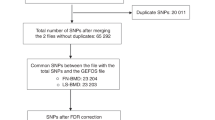

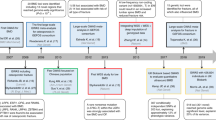

Bone mineral density (BMD) is a heritable complex trait used in the clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis and the assessment of fracture risk. We performed meta-analysis of five genome-wide association studies of femoral neck and lumbar spine BMD in 19,195 subjects of Northern European descent. We identified 20 BMD loci that reached genome-wide significance (GWS; P < 5 × 10−8), of which 13 map to regions not previously associated with this trait: 1p31.3 (GPR177), 2p21 (SPTBN1), 3p22 (CTNNB1), 4q21.1 (MEPE), 5q14 (MEF2C), 7p14 (STARD3NL), 7q21.3 (FLJ42280), 11p11.2 (LRP4, ARHGAP1, F2), 11p14.1 (DCDC5), 11p15 (SOX6), 16q24 (FOXL1), 17q21 (HDAC5) and 17q12 (CRHR1). The meta-analysis also confirmed at GWS level seven known BMD loci on 1p36 (ZBTB40), 6q25 (ESR1), 8q24 (TNFRSF11B), 11q13.4 (LRP5), 12q13 (SP7), 13q14 (TNFSF11) and 18q21 (TNFRSF11A). The many SNPs associated with BMD map to genes in signaling pathways with relevance to bone metabolism and highlight the complex genetic architecture that underlies osteoporosis and variation in BMD.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

11 October 2009

NOTE: In the version of this article initially published online, the seventh and eighth sentences under the heading “Combined effect of the 20 GWS BMD loci and fracture risk” were incorrect. The correct wording is as follows: “The compound FN-BMD allelic score was significantly associated with the risk of incident nonvertebral fracture in the Rotterdam Study dataset (HR = 1.042, 95% CI [1.003, 1.084]; P = 0.04), whereas it was borderline significant for association with the risk of vertebral fracture (OR = 1.061, 95% CI [0.997, 1.129]; P = 0.06). In contrast, the compound LS-BMD allelic score was significantly associated with the risk of vertebral fracture (OR = 1.061, 95% CI [1.009, 1.116]; P = 0.02), whereas it was not significant for association with the risk of incident nonvertebral fracture (HR = 1.025, 95% CI [0.993, 1.058]; P = 0.13).” The error has been corrected for all versions of the article.

References

Ellies, D.L. et al. Bone density ligand, Sclerostin, directly interacts with LRP5 but not LRP5G171V to modulate Wnt activity. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21, 1738–1749 (2006).

Theoleyre, S. et al. The molecular triad Opg/RANK/RANKL: involvement in the orchestration of pathophysiological bone remodeling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 15, 457–475 (2004).

Ioannidis, J.P. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide scans provides evidence for sex- and site-specific regulation of bone mass. J. Bone Miner. Res. 22, 173–183 (2007).

Ioannidis, J.P. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med. 2, e124 (2005).

Ioannidis, J.P. Genetic associations: false or true? Trends Mol. Med. 9, 135–138 (2003).

Ioannidis, J.P. et al. Differential genetic effects of ESR1 gene polymorphisms on osteoporosis outcomes. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 292, 2105–2114 (2004).

Langdahl, B.L. et al. Large-scale analysis of association between polymorphisms in the transforming growth factor beta 1 gene (TGFB1) and osteoporosis: the GENOMOS study. Bone 42, 969–981 (2008).

Ralston, S.H. et al. Large-scale evidence for the effect of the COLIA1 Sp1 polymorphism on osteoporosis outcomes: the GENOMOS study. PLoS Med. 3, e90 (2006).

Uitterlinden, A.G. et al. The association between common vitamin D receptor gene variations and osteoporosis: a participant-level meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 145, 255–264 (2006).

van Meurs, J.B. et al. Large-scale analysis of association between LRP5 and LRP6 variants and osteoporosis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 299, 1277–1290 (2008).

McCarthy, M.I. et al. Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 356–369 (2008).

Styrkarsdottir, U. et al. New sequence variants associated with bone mineral density. Nat. Genet. 41, 15–17 (2009).

Styrkarsdottir, U. et al. Multiple genetic loci for bone mineral density and fractures. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 2355–2365 (2008).

Kanis, J.A., Delmas, P., Burckhardt, P., Cooper, C. & Torgerson, D. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of osteoporosis. The European Foundation for Osteoporosis and Bone Disease. Osteoporos. Int. 7, 390–406 (1997).

Blake, G.M., Knapp, K.M., Spector, T.D. & Fogelman, I. Predicting the risk of fracture at any site in the skeleton: are all bone mineral density measurement sites equally effective? Calcif. Tissue Int. 78, 9–17 (2006).

Peacock, M., Turner, C.H., Econs, M.J. & Foroud, T. Genetics of osteoporosis. Endocr. Rev. 23, 303–326 (2002).

Weedon, M.N. et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 20 loci that influence adult height. Nat. Genet. 40, 575–583 (2008).

Gudbjartsson, D.F. et al. Many sequence variants affecting diversity of adult human height. Nat. Genet. 40, 609–615 (2008).

Visscher, P.M. Sizing up human height variation. Nat. Genet. 40, 489–490 (2008).

Devlin, B. & Roeder, K. Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics 55, 997–1004 (1999).

Willer, C.J. et al. Six new loci associated with body mass index highlight a neuronal influence on body weight regulation. Nat. Genet. 41, 25–34 (2009).

Pe'er, I., Yelensky, R., Altshuler, D. & Daly, M.J. Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genet. Epidemiol. 32, 381–385 (2008).

Frazer, K.A. et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature 449, 851–861 (2007).

Richards, J.B. et al. Bone mineral density, osteoporosis, and osteoporotic fractures: a genome-wide association study. Lancet 371, 1505–1512 (2008).

Bänziger, C. et al. Wntless, a conserved membrane protein dedicated to the secretion of Wnt proteins from signaling cells. Cell 125, 509–522 (2006).

Matsuda, A. et al. Large-scale identification and characterization of human genes that activate NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Oncogene 22, 3307–3318 (2003).

Glass, D.A. II et al. Canonical Wnt signaling in differentiated osteoblasts controls osteoclast differentiation. Dev. Cell 8, 751–764 (2005).

Potthoff, M.J. et al. Histone deacetylase degradation and MEF2 activation promote the formation of slow-twitch myofibers. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 2459–2467 (2007).

Cho, Y.S. et al. A large-scale genome-wide association study of Asian populations uncovers genetic factors influencing eight quantitative traits. Nat. Genet. 41, 527–534 (2009).

Smits, P. et al. The transcription factors L-Sox5 and Sox6 are essential for cartilage formation. Dev. Cell 1, 277–290 (2001).

Zhou, G. et al. Dominance of SOX9 function over RUNX2 during skeletogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 19004–19009 (2006).

Reiner, O. et al. The evolving doublecortin (DCX) superfamily. BMC Genomics 7, 188 (2006).

Kim, S.H. et al. The forkhead transcription factor Foxc2 stimulates osteoblast differentiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 386, 532–536 (2009).

Nifuji, A., Miura, N., Kato, N., Kellermann, O. & Noda, M. Bone morphogenetic protein regulation of forkhead/winged helix transcription factor Foxc2 (Mfh1) in a murine mesodermal cell line C1 and in skeletal precursor cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 16, 1765–1771 (2001).

Winnier, G.E., Hargett, L. & Hogan, B.L. The winged helix transcription factor MFH1 is required for proliferation and patterning of paraxial mesoderm in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 11, 926–940 (1997).

Stankiewicz, P. et al. Genomic and genic deletions of the FOX gene cluster on 16q24.1 and inactivating mutations of FOXF1 cause alveolar capillary dysplasia and other malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84, 780–791 (2009).

Tang, Y. et al. Disruption of transforming growth factor-β signaling in ELF β-spectrin-deficient mice. Science 299, 574–577 (2003).

Alford, A.I. & Hankenson, K.D. Matricellular proteins: extracellular modulators of bone development, remodeling, and regeneration. Bone 38, 749–757 (2006).

Gowen, L.C. et al. Targeted disruption of the osteoblast/osteocyte factor 45 gene (OF45) results in increased bone formation and bone mass. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1998–2007 (2003).

Malaval, L. et al. Bone sialoprotein plays a functional role in bone formation and osteoclastogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 205, 1145–1153 (2008).

Yoshitake, H., Rittling, S.R., Denhardt, D.T. & Noda, M. Osteopontin-deficient mice are resistant to ovariectomy-induced bone resorption. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 8156–8160 (1999).

Meyers, V.E., Zayzafoon, M., Douglas, J.T. & McDonald, J.M. RhoA and cytoskeletal disruption mediate reduced osteoblastogenesis and enhanced adipogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells in modeled microgravity. J. Bone Miner. Res. 20, 1858–1866 (2005).

Wang, L., Yang, L., Debidda, M., Witte, D. & Zheng, Y. Cdc42 GTPase-activating protein deficiency promotes genomic instability and premature aging-like phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 1248–1253 (2007).

McKinsey, T.A., Zhang, C.L., Lu, J. & Olson, E.N. Signal-dependent nuclear export of a histone deacetylase regulates muscle differentiation. Nature 408, 106–111 (2000).

Schroeder, T.M. & Westendorf, J.J. Histone deacetylase inhibitors promote osteoblast maturation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 20, 2254–2263 (2005).

Kang, J.S., Alliston, T., Delston, R. & Derynck, R. Repression of Runx2 function by TGF-β through recruitment of class II histone deacetylases by Smad3. EMBO J. 24, 2543–2555 (2005).

Ioannidis, J.P., Thomas, G. & Daly, M.J. Validating, augmenting and refining genome-wide association signals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 318–329 (2009).

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database (McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, and National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/>.

McKusick, V.A. Mendelian Inheritance in Man. A Catalog of Human Genes and Genetic Disorders (Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland, USA, 1998).

Hofman, A. et al. The Rotterdam Study: 2010 objectives and design update. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 24, 553–572 (2009).

Hofman, A., Grobbee, D.E., de Jong, P.T. & van den Ouweland, F.A. Determinants of disease and disability in the elderly: the Rotterdam Elderly Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 7, 403–422 (1991).

Aulchenko, Y.S. et al. Linkage disequilibrium in young genetically isolated Dutch population. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 12, 527–534 (2004).

Arden, N.K., Baker, J., Hogg, C., Baan, K. & Spector, T.D. The heritability of bone mineral density, ultrasound of the calcaneus and hip axis length: a study of postmenopausal twins. J. Bone Miner. Res. 11, 530–534 (1996).

Dawber, T.R., Kannel, W.B. & Lyell, L.P. An approach to longitudinal studies in a community: the Framingham Study. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 107, 539–556 (1963).

Kannel, W.B., Feinleib, M., McNamara, P.M., Garrison, R.J. & Castelli, W.P. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. The Framingham offspring study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 110, 281–290 (1979).

Splansky, G.L. et al. The Third Generation Cohort of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Framingham Heart Study: design, recruitment, and initial examination. Am. J. Epidemiol. 165, 1328–1335 (2007).

Price, A.L. et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 38, 904–909 (2006).

International HapMap Consortium. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature 449, 851–861 (2007).

Li, Y. & Abecasis, G.R. Mach 1.0: rapid haplotype reconstruction and missing genotype inference. Am. J. Hum. Genet. S79, 2290 (2006).

Marchini, J., Howie, B., Myers, S., McVean, G. & Donnelly, P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat. Genet. 39, 906–913 (2007).

Kutyavin, I.V. et al. A novel endonuclease IV post-PCR genotyping system. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, e128 (2006).

Little, J. et al. Strengthening the reporting of genetic association studies (STREGA): an extension of the STROBE statement. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 24, 37–55 (2009).

Abecasis, G.R., Cherny, S.S., Cookson, W.O. & Cardon, L.R. Merlin–rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat. Genet. 30, 97–101 (2002).

Therneau, T. Kinship: mixed effects Cox models, sparse matrices, and modelling data from large pedigrees. R package version 1.1.0, edn. 19 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2008).

Aulchenko, Y.S., Ripke, S., Isaacs, A. & van Duijn, C.M. GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics 23, 1294–1296 (2007).

R Developmental Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2007).

de Bakker, P.I. et al. Practical aspects of imputation-driven meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, R122–R128 (2008).

Stata Statistical Software. Release 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA, 2007).

Grundberg, E. et al. Systematic assessment of the human osteoblast transcriptome in resting and induced primary cells. Physiol. Genomics 33, 301–311 (2008).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Rivadeneira, F. et al. Estrogen receptor beta (ESR2) polymorphisms in interaction with estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF1) variants influence the risk of fracture in postmenopausal women. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21, 1443–1456 (2006).

Schuit, S.C. et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone 34, 195–202 (2004).

McCloskey, E.V. et al. The assessment of vertebral deformity: a method for use in population studies and clinical trials. Osteoporos. Int. 3, 138–147 (1993).

Acknowledgements

We thank all study participants for making this work possible. This research and the Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis (GEFOS) consortium (http://www.gefos.org) have been funded by the European Commission (HEALTH-F2-2008-201865-GEFOS). Rotterdam Study (RS): This study was funded by the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research NWO Investments (175.010.2005.011, 911-03-012), the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (014-93-015; RIDE2) and the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI)/Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) project 050-060-810. We thank P. Arp, M. Jhamai, M. Moorhouse, M. Verkerk and S. Bervoets for their help in creating the GWAS database. The Rotterdam Study is funded by Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Netherlands Organization for the Health Research and Development (ZonMw), the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (RIDE), the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the Ministry for Health, Welfare and Sports, the European Commission (DG XII) and the Municipality of Rotterdam. We thank the staff from the Rotterdam Study, particularly L. Buist and J.H. van den Boogert and also the participating general practitioners and pharmacists. Erasmus Rucphen Family (ERF): The study was supported by grants from The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), Erasmus MC and the Centre for Medical Systems Biology (CMSB). We thank all general practitioners for their contributions, P. Veraart for help in genealogy, J. Vergeer for supervision of the laboratory work and P. Snijders for help in data collection. Twins UK (TUK): The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the Arthritis Research Campaign, the Chronic Disease Research Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (J.B.R.), the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis (J.B.R.) and the European Union FP-5 GenomEUtwin Project (QLG2-CT-2002-01254). The study also receives support from a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre award to Guy's & St. Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King's College London. We thank the staff of the Twins UK study; the DNA Collections and Genotyping Facilities at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute for sample preparation; Quality Control of the Twins UK cohort for genotyping (in particular A. Chaney, R. Ravindrarajah, D. Simpkin, C. Hinds and T. Dibling); P. Martin and S. Potter of the DNA and Genotyping Informatics teams for data handling; Le Centre National de Génotypage, France, led by M. Lathrop, for genotyping; Duke University, North Carolina, USA, led by D. Goldstein, for genotyping; and the Finnish Institute of Molecular Medicine, Finnish Genome Center, University of Helsinki, led by A. Palotie. Icelandic deCODE Study (dCG): We thank the staff of the deCODE core facilities and recruitment centre for their important contributions to this work. Framingham Osteoporosis Study (FOS): The study was funded by grants from the US National Institute for Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and National Institute on Aging (R01 AR/AG 41398; DPK and R01 AR 050066; DK). The Framingham Heart Study of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health and Boston University School of Medicine were supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Framingham Heart Study (N01-HC-25195) and its contract with Affymetrix, Inc. for genotyping services (N02-HL-6-4278). Analyses reflect intellectual input and resource development from the Framingham Heart Study investigators participating in the SNP Health Association Resource (SHARe) project. A portion of this research was conducted using the Linux Cluster for Genetic Analysis (LinGA-II) funded by the Robert Dawson Evans Endowment of the Department of Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center. eQTL HOb Study: The study was supported by Genome Quebec, Genome Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). T.P. holds a Canada Research Chair. We thank O. Nilsson, H. Mallmin and Ö. Ljunggren at the Departments of Surgical and Medical Sciences, Uppsala University Hospital, Sweden, for large-scale collection of primary bone samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

F.R., K.E., B.V.H., F.K.K. and J.P.A.I. ran meta-analysis; F.R., K.E., B.V.H., Y.-H.H., J.B.R., M.C.Z., N.A., Y.S.A., L.A.C., S.D., N.S., G.T. and Y.Z. ran statistical analysis in studies; F.R., U.S., P.D., J.B.v.M., U.T. and A.G.U. coordinated GWA genotyping of studies; E.G. and T.P. did expression studies; F.R., U.S., M.C.Z., A.H., B.O., H.A.P.P., G.S., G.T., F.M.K.W., S.G.W., C.M.v.D., T.S., D.P.K. and A.G.U. coordinated/collected phenotypic information; U.S., L.A.C., A.H., A.K., D.K., B.O., H.A.P.P., U.T., C.M.v.D., T.S., D.P.K., K.S. and A.G.U. designed studies; F.R., U.S., J.B.v.M., T.S., U.T., S.H.R., J.P.A.I. and A.G.U. established the consortium and U.T., S.H.R., J.P.A.I. and A.G.U. obtained funding; all authors interpreted results; all authors critically read the manuscript; and F.R. wrote the manuscript draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The coauthors affiliated with deCODE Genetics in Reykjavík Iceland withhold stock options in that company.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Tables 1–10 and Supplementary Figures 1–3. (PDF 1495 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

the Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis (GEFOS) Consortium. Twenty bone-mineral-density loci identified by large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 41, 1199–1206 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.446

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.446

This article is cited by

-

SP7: from Bone Development to Skeletal Disease

Current Osteoporosis Reports (2023)

-

Bone Trans-omics: Integrating Omics to Unveil Mechanistic Molecular Networks Regulating Bone Biology and Disease

Current Osteoporosis Reports (2023)

-

Zebrafish as a Model for Osteoporosis: Functional Validations of Genome-Wide Association Studies

Current Osteoporosis Reports (2023)

-

Aberrant paracrine signalling for bone remodelling underlies the mutant histone-driven giant cell tumour of bone

Cell Death & Differentiation (2022)

-

Pathways Controlling Formation and Maintenance of the Osteocyte Dendrite Network

Current Osteoporosis Reports (2022)