Abstract

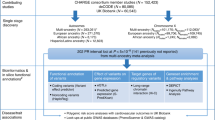

Brugada syndrome is a rare cardiac arrhythmia disorder, causally related to SCN5A mutations in around 20% of cases1,2,3. Through a genome-wide association study of 312 individuals with Brugada syndrome and 1,115 controls, we detected 2 significant association signals at the SCN10A locus (rs10428132) and near the HEY2 gene (rs9388451). Independent replication confirmed both signals (meta-analyses: rs10428132, P = 1.0 × 10−68; rs9388451, P = 5.1 × 10−17) and identified one additional signal in SCN5A (at 3p21; rs11708996, P = 1.0 × 10−14). The cumulative effect of the three loci on disease susceptibility was unexpectedly large (Ptrend = 6.1 × 10−81). The association signals at SCN5A-SCN10A demonstrate that genetic polymorphisms modulating cardiac conduction4,5,6,7 can also influence susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmia. The implication of association with HEY2, supported by new evidence that Hey2 regulates cardiac electrical activity, shows that Brugada syndrome may originate from altered transcriptional programming during cardiac development8. Altogether, our findings indicate that common genetic variation can have a strong impact on the predisposition to rare diseases.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

04 October 2013

In the version of this article initially published, Martin Borggrefe and Rainer Schimpf were inadvertently omitted from the author list. Both are affiliated with the First Department of Medicine (Cardiology), University Medical Center, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University, Mannheim, Germany, and with DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research), partner site Heidelberg/Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany. In addition, one of the study's funding sources (the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, research grant for cardiovascular diseases, H24-033) was omitted from the Acknowledgments section. These errors have been corrected in the HTML and PDF versions of the article.

References

Brugada, P. & Brugada, J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 20, 1391–1396 (1992).

Antzelevitch, C. et al. Brugada syndrome: Report of the Second Consensus Conference Endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation 111, 659–670 (2005).

Kapplinger, J.D. et al. An international compendium of mutations in the SCN5A-encoded cardiac sodium channel in patients referred for Brugada syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm 7, 33–46 (2010).

Chambers, J.C. et al. Genetic variation in SCN10A influences cardiac conduction. Nat. Genet. 42, 149–152 (2010).

Holm, H. et al. Several common variants modulate heart rate, PR interval and QRS duration. Nat. Genet. 42, 117–122 (2010).

Pfeufer, A. et al. Genome-wide association study of PR interval. Nat. Genet. 42, 153–159 (2010).

Sotoodehnia, N. et al. Common variants in 22 loci are associated with QRS duration and cardiac ventricular conduction. Nat. Genet. 42, 1068–1076 (2010).

Leimeister, C., Externbrink, A., Klamt, B. & Gessler, M. Hey genes: a novel subfamily of hairy- and Enhancer of split related genes specifically expressed during mouse embryogenesis. Mech. Dev. 85, 173–177 (1999).

Straus, S.M.J.M. et al. The incidence of sudden cardiac death in the general population. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 57, 98–102 (2004).

Priori, S.G. et al. Task Force on Sudden Cardiac Death, European Society of Cardiology, Summary of Recommendations. Europace 4, 3–18 (2002).

Chen, Q. et al. Genetic basis and molecular mechanism for idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Nature 392, 293–296 (1998).

Wilde, A.A.M. et al. The pathophysiological mechanism underlying Brugada syndrome: depolarization versus repolarization. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 49, 543–553 (2010).

Crotti, L. et al. Spectrum and prevalence of mutations involving BrS1-through BrS12-susceptibility genes in a cohort of unrelated patients referred for Brugada syndrome genetic testing: implications for genetic testing. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 60, 1410–1418 (2012).

Priori, S.G. et al. Clinical and genetic heterogeneity of right bundle branch block and ST-segment elevation syndrome: a prospective evaluation of 52 families. Circulation 102, 2509–2515 (2000).

Probst, V. et al. SCN5A mutations and the role of genetic background in the pathophysiology of Brugada syndrome (clinical perspective). Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2, 552–557 (2009).

Schulze-Bahr, E. et al. Sodium channel gene (SCN5A) mutations in 44 index patients with Brugada syndrome: different incidences in familial and sporadic disease. Hum. Mutat. 21, 651–652 (2003).

Hermida, J.-S. et al. Prospective evaluation of the familial prevalence of the Brugada syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol. 106, 1758–1762 (2010).

Balkau, B. An epidemiologic survey from a network of French Health Examination Centres, (D.E.S.I.R.): epidemiologic data on the insulin resistance syndrome. Rev. Epidemiol. Sante Publique 44, 373–375 (1996).

Arking, D.E. et al. A common genetic variant in the NOS1 regulator NOS1AP modulates cardiac repolarization. Nat. Genet. 38, 644–651 (2006).

Newton-Cheh, C. et al. Common variants at ten loci influence QT interval duration in the QTGEN Study. Nat. Genet. 41, 399–406 (2009).

Pfeufer, A. et al. Common variants at ten loci modulate the QT interval duration in the QTSCD Study. Nat. Genet. 41, 407–414 (2009).

Eijgelsheim, M. et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies multiple loci related to resting heart rate. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 3885–3894 (2010).

Marroni, F. et al. A genome-wide association scan of RR and QT interval duration in 3 European genetically isolated populations: the EUROSPAN project. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2, 322–328 (2009).

Sladek, R. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature 445, 881–885 (2007).

Manolio, T.A. et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 461, 747–753 (2009).

Akopian, A.N., Sivilotti, L. & Wood, J.N. A tetrodotoxin-resistant voltage-gated sodium channel expressed by sensory neurons. Nature 379, 257–262 (1996).

Verkerk, A.O. et al. Functional Nav1.8 channels in intracardiac neurons: the link between SCN10A and cardiac electrophysiology. Circ. Res. 111, 333–343 (2012).

Yang, T. et al. Blocking Scn10a channels in heart reduces late sodium current and is antiarrhythmic. Circ. Res. 111, 322–332 (2012).

Pallante, B.A. et al. Contactin-2 expression in the cardiac Purkinje fiber network. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 3, 186–194 (2010).

van den Boogaard, M. et al. Genetic variation in T-box binding element functionally affects SCN5A/SCN10A enhancer. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 2519–2530 (2012).

Arnolds, D.E. et al. TBX5 drives Scn5a expression to regulate cardiac conduction system function. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 2509–2518 (2012).

Shao, W., Halachmi, S. & Brown, M. ERAP140, a conserved tissue-specific nuclear receptor coactivator. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 3358–3372 (2002).

Fischer, A. & Gessler, M. Hey genes in cardiovascular development. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 13, 221–226 (2003).

Xin, M. et al. Essential roles of the bHLH transcription factor Hrt2 in repression of atrial gene expression and maintenance of postnatal cardiac function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 7975–7980 (2007).

Kokubo, H. et al. Targeted disruption of hesr2 results in atrioventricular valve anomalies that lead to heart dysfunction. Circ. Res. 95, 540–547 (2004).

Gessler, M. et al. Mouse gridlock: no aortic coarctation or deficiency, but fatal cardiac defects in Hey2−/− mice. Curr. Biol. 12, 1601–1604 (2002).

Sakata, Y. et al. Ventricular septal defect and cardiomyopathy in mice lacking the transcription factor CHF1/Hey2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 16197–16202 (2002).

Koibuchi, N. & Chin, M.T. CHF1/Hey2 plays a pivotal role in left ventricular maturation through suppression of ectopic atrial gene expression. Circ. Res. 100, 850–855 (2007).

Fischer, A. et al. Hey basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors are repressors of GATA4 and GATA6 and restrict expression of the GATA target gene ANF in fetal hearts. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 8960–8970 (2005).

Remme, C.A. et al. The cardiac sodium channel displays differential distribution in the conduction system and transmural heterogeneity in the murine ventricular myocardium. Basic Res. Cardiol. 104, 511–522 (2009).

Nademanee, K. et al. Prevention of ventricular fibrillation episodes in Brugada syndrome by catheter ablation over the anterior right ventricular outflow tract epicardium. Circulation 123, 1270–1279 (2011).

Sakuma, M. et al. Incidence and outcome of osteoporotic fractures in 2004 in Sado City, Niigata Prefecture, Japan. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 26, 373–378 (2008).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Frayley, C. & Raftery, A.E. MCLUST Version 3 for R: Normal Mixture Modeling and Model-Based Clustering (Department of Statistics, University of Washington, Seattle, 2006).

Byers, S. & Raftery, A.E. Nearest-neighbor clutter removal for estimating features in spatial point processes. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 93, 577–584 (1998).

Postel-Vinay, S. et al. Common variants near TARDBP and EGR2 are associated with susceptibility to Ewing sarcoma. Nat. Genet. 44, 323–327 (2012).

Pirinen, M., Donnelly, P. & Spencer, C.C.A. Including known covariates can reduce power to detect genetic effects in case-control studies. Nat. Genet. 44, 848–851 (2012).

Stouffer, S.A., Suchman, E.A., Devinney, L.C., Star, S.A. & Williams, R.M. Jr. The American Soldier: Adjustment During Army Life (Studies in Social Psychology in World War II, Vol. 1) (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1949).

Willer, C.J., Li, Y. & Abecasis, G.R. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics 26, 2190–2191 (2010).

Delaneau, O., Marchini, J. & Zagury, J.-F. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat. Methods 9, 179–181 (2012).

Marchini, J., Howie, B., Myers, S., McVean, G. & Donnelly, P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat. Genet. 39, 906–913 (2007).

Howie, B., Marchini, J. & Stephens, M. Genotype imputation with thousands of genomes. G3 1, 457–470 (2011).

Kolder, I.C.R.M., Tanck, M.W.T. & Bezzina, C.R. Common genetic variation modulating cardiac ECG parameters and susceptibility to sudden cardiac death. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 52, 620–629 (2012).

Meyre, D. et al. Genome-wide association study for early-onset and morbid adult obesity identifies three new risk loci in European populations. Nat. Genet. 41, 157–159 (2009).

Higgins, J.P.T. & Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 21, 1539–1558 (2002).

Little, R.J.A. & Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data (Wiley and Sons, New York, 1987).

Rubin, D.B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys (2008) http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/book/10.1002/9780470316696.

Lin, S., Chakravarti, A. & Cutler, D.J. Exhaustive allelic transmission disequilibrium tests as a new approach to genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 36, 1181–1188 (2004).

Wray, N.R., Yang, J., Goddard, M.E. & Visscher, P.M. The genetic interpretation of area under the ROC curve in genomic profiling. PLoS Genet. 6, e1000864 (2010).

Remme, C.A. et al. Overlap syndrome of cardiac sodium channel disease in mice carrying the equivalent mutation of human SCN5A-1795insD. Circulation 114, 2584–2594 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Beekman, C. de Gier-de Vries, B. de Jonge and the Genomic Platform of Nantes (Biogenouest Genomics) for technical support. We are also grateful to the French Clinical Network against Inherited Cardiac Arrhythmias, which includes the University Hospitals of Nantes, Bordeaux, Rennes, Tours, Brest, Strasbourg, La Réunion, Angers and Montpellier. This study was funded by research grants from the Leducq Foundation (CVD-05; Alliance Against Sudden Cardiac Death), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (grant-in-aid for the Project in Sado for Total Health, PROST), the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (research grant for cardiovascular diseases, H24-033),the French Ministry of Health (PHRC AOR04070, P040411 and PHRCI DGS2001/0248), INSERM (ATIP-Avenir program to R.R.) and the French Regional Council of Pays-de-la-Loire. This research was also supported by the Netherlands Heart Institute (grant 061.02 to C.A.R. and C.R.B.) and the Division for Earth and Life Sciences (ALW; project 836.09.003 to C.A.R.) with financial aid from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). C.R.B. acknowledges support from the Netherlands Heart Foundation (NHS 2007B202 and 2009B066). J.B. was supported by a research grant from the European Society of Cardiology and the Netherlands Heart Institute (ICIN) and by the French-Dutch Academy through the Van Gogh program. E.S.-B. was supported by the Interdisziplinären Zentrums für Klinische Forschung (IZKF) of the University of Münster and the Collaborative Research Center SFB656. M.G. acknowledges support from the German Research Foundation (DFG-SFB 688 and TP A16). This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of Denis Escande, who founded the Leducq Foundation Network Alliance Against Sudden Cardiac Death.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.R.B., J.-J.S. and R.R. designed the study. Y.M. and J.-B.G. evaluated all ECGs. C.D. coordinated the statistical analyses, which C.D., F.S., P.L. and E.C. carried out. F.G., A.D., S.L. and E.C. performed genotyping for the GWAS. J.B., J.V., V. Portero and K.H. carried out genotyping in the validation sets. A.A.W., H.L.T., H.L.M., V. Probst, F.K., S. Bézieau, S.C., S.K., B.M.B., E.S.-B., S.Z., L.C., P.J.S., F.D., M.T., C.A., S. Bartkowiak, M.B., R.S., P.G., V.F., A.L., D.M.R., P.W., E.R.B., R.B., J.T.-H., M.S.O., N.M., A.N., M.H., S.O., K.H., W.S. and T.A. recruited subjects and participated in clinical and molecular diagnostics. P.F., B.B., O.L., H.W., T.M. and N.E. provided controls. M.G., D.W. and C.W. provided the mice. C.A.R., A.O.V., B.J.B. and R.W. acquired and analyzed electrophysiological data. V.M.C., C.A.R. and R.W. acquired and analyzed protein expression data. C.R.B., J.B., C.A.R., C.D., J.-J.S., V.M.C., R.C. and R.R. interpreted the data. C.R.B., J.-J.S., V. Probst, D.M.R., A.A.W., S.K., E.S.-B., A.L. and R.R. obtained funding. C.R.B., J.B., C.D. and R.R. drafted the manuscript. All coauthors critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. C.R.B. and R.R. led the study together.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–13 and Supplementary Tables 1–6 (PDF 5962 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bezzina, C., Barc, J., Mizusawa, Y. et al. Common variants at SCN5A-SCN10A and HEY2 are associated with Brugada syndrome, a rare disease with high risk of sudden cardiac death. Nat Genet 45, 1044–1049 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2712

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2712

This article is cited by

-

Stem cell models of inherited arrhythmias

Nature Cardiovascular Research (2024)

-

Left ventricular hypertrophy and metabolic resetting in the Notch3-deficient adult mouse heart

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

The underlying molecular mechanisms and biomarkers of plaque vulnerability based on bioinformatics analysis

European Journal of Medical Research (2022)

-

CLIN_SKAT: an R package to conduct association analysis using functionally relevant variants

BMC Bioinformatics (2022)

-

Risk stratification of sudden cardiac death in Brugada syndrome: an updated review of literature

The Egyptian Heart Journal (2022)