Abstract

The role human activities play in reshaping biodiversity is increasingly apparent in terrestrial ecosystems. However, the responses of entire marine assemblages are not well-understood, in part, because few monitoring programs incorporate both spatial and temporal replication. Here, we analyse an exceptionally comprehensive 29-year time series of North Atlantic groundfish assemblages monitored over 5° latitude to the west of Scotland. These fish assemblages show no systematic change in species richness through time, but steady change in species composition, leading to an increase in spatial homogenization: the species identity of colder northern localities increasingly resembles that of warmer southern localities. This biotic homogenization mirrors the spatial pattern of unevenly rising ocean temperatures over the same time period suggesting that climate change is primarily responsible for the spatial homogenization we observe. In this and other ecosystems, apparent constancy in species richness may mask major changes in species composition driven by anthropogenic change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Anthropocene1,2 is characterized by marked changes in the diversity of natural assemblages across the Earth3. There is, however, increasing evidence that community responses to anthropogenic impacts are complex and scale dependent4. Although heavily transformed terrestrial habitats exhibit species loss3, recent meta-analyses have detected no systematic change in local α diversity5,6. In contrast, temporal turnover (temporal β diversity)7 in local assemblages is occurring at rates in excess of background levels predicted by null and neutral models6. β diversity measures change in community composition over time (or space), and will be influenced by a range of processes including species invasion and shifts in species ranges. Dornelas et al.6 hypothesized that elevated rates of turnover could be a result of increasing biotic homogenization, a process whereby previously differentiated assemblages increasingly resemble one another in species composition. This hypothesis of a linkage between untrending local species richness, high turnover in local species composition and declining spatial β diversity (increasing homogenization) has not yet been tested in any ecosystem.

To date, investigations of biotic homogenization have focused on direct human influences on freshwater and terrestrial assemblages8. For example, deliberate introductions of gamefish are largely responsible for the greater homogeneity of contemporary freshwater fish assemblages in the United States compared with the time of the European settlement9. However, open water marine communities–especially those in offshore localities–are arguably less vulnerable to biotic homogenization than terrestrial ones because they are initially less spatially differentiated10,11,12 and less subject to some of the direct human interventions driving terrestrial homogenization such as species introductions and habitat modification. Nonetheless, for many marine species13, recent shifts in geographic ranges and phenology have been linked to anthropogenic climate change14,15,16,17 and temporal turnover in marine assemblages has also increased relative to null expectations6. This makes offshore marine ecosystems a good candidate for testing the role of elevated community turnover in homogenization.

Using data collected during a systematic Scottish groundfish survey, we probe marine community shifts by quantifying temporal trends in α and β diversity over almost three decades. We show that biotic homogenization is driven by elevated species turnover, transforming marine assemblages in ways that resemble terrestrial assemblages.

Results

α and β diversity

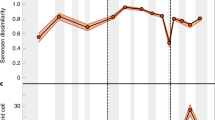

With a total regional count of 131 species recorded, and an average local species richness of 21.5 (per 30 latitudinal band, per year), there was no systematic change in rarefied species richness across the 29 years of sampling (ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, r2=0.005, P=0.15, n=252, see Supplementary Figure 2), although the nine 30′ latitudinal bands exhibit heterogeneous temporal trends in species richness (α diversity; left-column panels, Fig. 1). In contrast to species richness, community composition shows increasing change relative to the baseline level within each latitudinal band, reflecting the temporal turnover that is typical for other marine, terrestrial and freshwater assemblages6 (Jaccard similarity; right-column panels, Fig. 1).

Trend lines (OLS regression) are colour coded red if significantly negative (P<0.05, n=28) and grey if not significant. (There were no significant positive slopes). See Supplementary Figure 2 for overall trend.

Biotic homogenization

It is possible for temporal turnover to be independent at each site, with no spatial signature. Instead, we found the temporal turnover depicted in Fig. 1 is at least partly explained by the species composition in the different latitudinal bands becoming progressively more similar over time (Fig. 2). Moreover, the distance-decay relationship in composition is less steep in later years, indicating that the northern and southern assemblages are now less differentiated from one another than they were three decades ago (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4). The result of these progressive changes is spatial biotic homogenization. These analyses confirm the hypothesis of Dornelas et al.6 that biotic homogenization can lead to a pattern of constant local species richness but increasing change in species composition. As further support, an analysis of spatial β diversity partitioning18,19 reveals that turnover in species identity is a consistently stronger driver of community reorganization than change in species richness (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 6). This result is in contrast to a recent meta-analysis20 which argued that changes in community similarity are driven by changes in species richness rather than changes in species composition.

The trend line (OLS regression) is shown (r2=0.42, P<0.001). Years in which the mean pairwise similarity is below the overall mean are shown in red, and those above the mean in blue. (A similar pattern emerges if Bray–Curtis similarity is used. See Supplementary Figure 3).

(a) Contour plot illustrating the relationship between Jaccard similarity and geographical distance (between latitudinal bands) over the duration of the study. The scale bar is to the right of the plot. The plot highlights increasing similarity through time, and greater homogenization across distant localities. (bottom) Distance-decay plots for an early ((b) 1986) and late ((c) 2013) year in the study. Median slopes shown. Distances (km) are between latitudinal bands. Compositional similarity of more distant localities increases through time (See Supplementary Figure 4 for further analysis of distance decay).

Water temperature

What forces are responsible for this widespread reorganization of marine fish assemblages? In this region of the North Atlantic, average ocean temperature has increased by c. 1 °C over the time frame of this study (Fig. 4a). Moreover, the south–north temperature gradient has decreased, so that the latitudinal bands in Fig. 1 are now thermally less differentiated than they used to be (Fig. 4d), meaning the northerly waters have increased in temperature more rapidly than the southerly waters. The mean annual pairwise difference in temperature between latitudinal bands (Fig. 4c) also declines through time. This decline mirrors the shift in community similarity indicating that, as water temperatures within the latitudinal bands converge over time, so too does the composition of the assemblages found there.

(a) Mean oceanographic surface temperature (depth<10 m) data in the first quarter of the year for the study area, in relation to year. The plot shows an increase in mean temperature through time (OLS regression, r2=0.22, n=162). (b) Relationship between temperature and latitude ignoring year, indicating that, on average, water temperature is cooler in more northern localities. (c) Box plot (median, quartiles, range and outliers) of pairwise temperature differences between latitudinal bands (analogous to the plot in Figure 2). Years in which the mean pairwise difference is below the overall mean are shown in red, and those above the mean in blue. There is a significant negative correlation (Spearman rs=−0.46, P=0.026, n=23) between mean annual temperature difference (this plot) and mean annual Jaccard dissimilarity (1-Jaccard). This indicates that the reduction in temperature difference parallels the reduction in differences in community composition. (d) Median slope of the relationship between temperature and latitude in each year of the study showing the steepness of the temperature gradient is declining over time. This trend is significant (Spearman rs=0.6, P=0.001, n=27).

Discussion

This investigation has documented rapid biotic homogenization in marine fish assemblages and argued that these community shifts are linked to climate. Other recent studies also highlight the potential of anthropogenic climate change21,22 to restructure marine communities. Climate velocity has been identified as a predictor of biotic change14. Our data show that these transformations are manifested over relatively small geographic areas and short time periods. It is likely that climate change acts in synergy with other anthropogenic stressors, such as pollution and over-exploitation23. However, although fishing has heavily impacted the North Atlantic for over a century, fishing effort (as reported landings and trawling hours) has not increased appreciably over the time period of this study24,25. Moreover, coastal human population densities in this region have remained low over the last three decades (for example, in 2011 mean human population density was 5.1 km−2).

Our perception of the natural state of marine communities is shaped by shifting baselines26. Contemporary accounts of Scottish waters in the eighteenth century attest to greater abundances of fish and sea mammals present at that time while drawing attention to the impacts that commercial fishing were having over 200 years ago27. The homogenization we document here is a continuation of the ongoing change in fish communities exposed to long-term anthropogenic pressures.

As we have shown, apparent constancy in widely used measures of α diversity (that is, lack of trends in local species richness) can mask enormous changes in an ecosystem. Local richness has, on average, been maintained over the duration of this study, with the same common species (including the Norway pout Trisopterus esmarkii, and Atlantic herring Clupea harengus) continuing to be overall dominants. However, our analyses reveal that groundfish communities off western Scotland are undergoing rapid reorganization. This change is driven by spatial homogenization, that is increasing similarity between locations 100 s of kms apart–possibly linked to climate change. Our data suggest that predicted changes in marine fish communities are already underway6,17. Biogeographical shifts in zooplankton species in the North East (NE) Atlantic28 provide further evidence that the pace of change is marine communities exceeds that in the terrestrial realm. This collapse of spatial β diversity (that is, increasing homogenization) is arguably a far greater and more pressing crisis than the loss of local species richness. As long as species are not globally extinct this homogenization is potentially reversible. However, this crisis is largely unrecognized, and adds to the challenges already facing marine biodiversity23.

Methods

Data

The Scottish groundfish survey takes place annually, in the seas to the north and west of Scotland (Supplementary Fig. 1). Sampling began in 1985. Trawling occurs in the first quarter of the year (January, February and March), and the same methodology has been used throughout. Each sample is a discrete trawl occurring at a precise geographical point within an International Council for the Exploration of the Seas (ICES) statistical rectangle (rectangles represent a 30′ latitude by 1° longitude grid cell). Sample number varies between rectangles in a given year. Species abundances are reported as catch per unit effort (that is the number of individuals per species caught during a 1 h trawl). Body size (standard length) is also recorded. We focus on the 35 rectangles (Supplementary Fig. 1) for which there are good community time series. A total of 131 taxa have been sampled in this study area over the 29 years of the survey. 126 of these taxa are finfish species, the remaining 5 macroinvertebrates (squid and macrocrustaceans). As 1992 and 1995 have substantially fewer samples than other years, we exclude them from our analyses. Species and temperature data were downloaded from the ICES portal (DATRAS Fish Survey Data ‘Scottish West Coast Survey For Commercial Fish Species 1985–2013’ (Available at https://datras.ices.dk, accessed on 2014)). Information on coastal human population density was obtained from National Records of Scotland, 2011 Census: Aggregate data (Scotland). UK Data Service Census Support. Downloaded from: http://infuse.mimas.ac.uk. This information is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/2) accessed on 2015.

Analysis

To understand how the composition of these groundfish communities is changing through time, relative to latitude, we first assign the rectangles to nine 30′ latitudinal bands. We then compile a community time series for each latitudinal band. Sample rarefaction (as in ref. 6) ensures equal sampling effort across bands and is used in the calculation of temporal α diversity (species richness) and temporal β diversity (Jaccard similarity (presence/absence) and Bray–Curtis similarity (quantitative)). We first calculate similarity in relation to the start of the survey. Next, for each year, we compute the pairwise compositional similarity of these latitudinal bands. We also construct distance-decay plots (similarity plotted against geographic distance) for each year. Quantile regression is used to fit the median slope of these relationships as it is robust against outliers. β diversity partitioning18,19 enables us to compute the relative contributions of turnover and nestedness to community change. To do this we recalculate Jaccard similarity as Jaccard dissimilarity because β diversity partitioning conventionally focuses on dissimilarity.

Geographical distances (in km) are calculated using the point distance tool in ArcGIS. Analyses use R statistical software29. The vegdist function in the R package vegan30 is used to compute similarities. The quantreg package31 is used to fit median slopes, and the betapart package19 to partition β diversity into components of turnover and nestedness.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Magurran, A. E. et al. Rapid biotic homogenization of marine fish assemblages. Nat. Commun. 6:8405 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9405 (2015).

References

Jackson, J. B. C. The future of the oceans past. Philos TransR Soc B: Biol. Sci. 365, 3765–3778 (2010).

Corlett, R. T. The Anthropocene concept in ecology and conservation. Trends Ecol Evol 30, 36–41 (2015).

Newbold, T. et al. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 520, 45–50 (2015).

McGill, B. J., Dornelas, M., Gotelli, N. J. & Magurran, A. E. Fifteen forms of biodiversity trend in the Anthropocene. Trends Ecol Evol 30, 104–113 (2015).

Vellend, M. et al. Global meta-analysis reveals no net change in local-scale plant biodiversity over time. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 19456–19459 (2013).

Dornelas, M. et al. Assemblage time series reveal biodiversity change but not systematic loss. Science 344, 296–299 (2014).

Magurran, A. & Henderson, P. Temporal turnover and the maintenance of diversity in ecological assemblages. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 365, 3611–3620 (2010).

Olden, J. D. Biotic homogenization: a new research agenda for conservation biogeography. J. Biogeogr. 33, 2027–2039 (2006).

Rahel, F. J. Homogenization of fish faunas across the United States. Science 288, 854–856 (2000).

Clarke, A. & Lidgard, S. Spatial patterns of diversity in the sea: bryozoan species richness in the North Atlantic. J. Anim. Ecol. 69, 799–814 (2000).

May, R. M. Biological diversity: differences between land and sea. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 343, 105–111 (1994).

Soininen, J., Lennon, J. J. & Hillebrand, H. A multivariate analysis of beta diversity across organisms and environments. Ecology 88, 2830–2838 (2007).

Hollowed, A. B. et al. Projected impacts of climate change on marine fish and fisheries. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 70, 1023–1037 (2013).

Pinsky, M. L., Worm, B., Fogarty, M. J., Sarmiento, J. L. & Levin, S. A. Marine taxa track local climate velocities. Science 341, 1239–1242 (2013).

Poloczanska, E. S. et al. Global imprint of climate change on marine life. Nature Clim. Chang. 3, 919–925 (2013).

Rose, G. A. On distributional responses of North Atlantic fish to climate change. ICES J Mar. Sci. 62, 1360–1374 (2005).

Rutterford, L. A. et al. Future fish distributions constrained by depth in warming seas. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 569–573 (2015).

Baselga, A. Partitioning the turnover and nestedness components of beta diversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 19, 134–143 (2010).

Baselga, A. et al. betapart: partitioning beta diversity into turnover and nestedness components. R package version 1.3. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=betapart 2013 .

Baiser, B., Olden, J. D., Record, S., Lockwood, J. L. & McKinney, M. L. Pattern and process of biotic homogenization in the New Pangaea. Proc. Biol. Sci. 279, 4772–4777 (2012).

Burrows, M. T. et al. The pace of shifting climate in marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Science 334, 652–655 (2011).

Burrows, M. T. et al. Geographical limits to species-range shifts are suggested by climate velocity. Nature 507, 492–495 (2014).

Jackson, J. B. C. Ecological extinction and evolution in the brave new ocean. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 11458–11465 (2008).

Worm, B. et al. Rebuilding global fisheries. Science 325, 578–585 (2009).

Scottish Government. Scottish Sea Fisheries Statistics 1985–2013, available at http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Agriculture-Fisheries/PubFisheries, accessed on 2015. .

Pauly, D. Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fsiheries. Trends Ecol. Evol. 10, 430 (1995).

Somerville, M. Queen Of Science: Recollections Of Mary Somerville 1780–1872Canongate Books (2001).

Gregory, B., Christophe, L. & Martin, E. Rapid biogeographical plankton shifts in the North Atlantic Ocean. Glob. Change Biol. 15, 1790–1803 (2009).

R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://www.R-project.org/ (Vienna, Austria, 2014).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.2-1. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (2015).

Koenker, R. quantreg: Quantile Regression. R package version 5.11. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=quantreg, 2015 .

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from ERC advanced grant BioTIME (250189). A.E.M. also thanks the Royal Society. M.D. is grateful for support from the Scottish Funding Council (MASTS-grant reference HR09011). N.J.G. is supported by U. S. NSF grants (DEB 1257625, DEB 1144055 and DEB 1136644). We thank the reviewers for their comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.E.M., M.D. and F.M. conceived the project in discussion with NJG and BMcG. F.M. was responsible for data handling and ran all the analyses. All authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-6 and Supplementary References (PDF 624 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Magurran, A., Dornelas, M., Moyes, F. et al. Rapid biotic homogenization of marine fish assemblages. Nat Commun 6, 8405 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9405

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9405

This article is cited by

-

Climatically promoted taxonomic homogenization of macroinvertebrates in unaffected streams varies along the river continuum

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Paleoreconstructions of ciliate communities reveal long-term ecological changes in temperate lakes

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Multiscale mechanisms underpin the ecological uniqueness of local fish assemblages in tropical coastal seascapes

Marine Biology (2022)

-

Habitat loss and range shifts contribute to ecological generalization among reef fishes

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2021)

-

The global loss of floristic uniqueness

Nature Communications (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.