Abstract

In recent years, a class of solid-state materials, called three-dimensional topological insulators, has emerged. In the bulk, a topological insulator behaves like an ordinary insulator with a band gap. At the surface, conducting gapless states exist showing remarkable properties such as helical Dirac dispersion and suppression of backscattering of spin-polarized charge carriers. The characterization and control of the surface states via transport experiments is often hindered by residual bulk contributions. Here we show that surface currents in Bi2Se3 can be controlled by circularly polarized light on a picosecond timescale with a fidelity near unity even at room temperature. We reveal the temporal separation of such ultrafast helicity-dependent surface currents from photo-induced thermoelectric and drift currents in the bulk. Our results uncover the functionality of ultrafast optoelectronic devices based on surface currents in topological insulators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Layered materials, such as Bi2Te3 (refs 1, 2), Sb (ref. 3), Bi2Se3 (refs 2, 4, 5, 6), Bi2Te2Se (ref. 7) and (Bi1-xSbx)2Te3 (ref. 8), are important narrow-bandgap semiconductors for tunable, high-performance infrared detectors and thermoelectric applications9. They have been demonstrated to be reference three-dimensional topological insulators10,11,12 exhibiting exceptional transport mobilities1,2,3,4,5,6. The latter suggests a reduced energy consumption that is very attractive for semiconductor devices in high-speed communication applications. In this respect, it is very advantageous that the helical surface states in topological insulators can be addressed by polarized light2,9,13,14,15,16. Particularly, the circular photogalvanic effect results from a helicity-dependent asymmetric optical excitation of spin-split surface states in momentum space, allowing the generation and control of spin-polarized surface currents in topological insulators by circularly polarized light17,18,19.

Here we demonstrate that such surface currents can be accessed and read-out independently of the bulk photocurrents on a picosecond timescale with near-unity fidelity. Therefore, our results open the avenue for a high-speed transmission of information based on topological insulators. Furthermore, our experiments address the connection between the non-equilibrium currents of hot electrons directly after the laser excitation and the time-averaged thermoelectric currents in these materials. A time-of-flight analysis of the photogenerated hot electrons yields a speed that is consistent with the group velocity at the Fermi-energy of the Bi2Se3.

Results

Time-resolved and time-integrated photocurrent spectroscopy

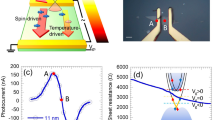

The investigated n-type Bi2Se3 films are embedded in a metal-topological insulator-metal photodetector geometry (Fig. 1a). We characterize the ultrafast photocurrents by an on-chip, time-domain THz photocurrent spectroscopy with a picosecond time-resolution (Fig. 1b and Methods)20,21,22. We excite the Bi2Se3 films with a circularly polarized pump pulse under an oblique angle θ (Fig. 1b). Such helical photons excite spins asymmetrically in k-space owing to angular momentum selection rules in Bi2Se3 (refs 9, 23). In turn, a net out-of-equilibrium spin polarization is acquired in the Dirac cone. After photoexcitation, spin and charge degrees of freedom relax on different timescales in the bulk and surface states of Bi2Se3 (ref. 24). For the surface states, spin depolarization, intraband cooling via surface electron-phonon scattering and interband electron-hole recombination occur on a sub-picosecond to picosecond timescale24,25,26.

(a) Circularly polarized photons of the pump pulse control surface currents in Bi2Se3. (b) The time-resolved photocurrent Isampling is read-out by a silicon-based Auston-switch triggered by a probe pulse at a time-delay Δt. The time-integrated photocurrent Iphoto is measured between the electronic contacts, which form two co-planar striplines. (c) Optical microscope image of a Bi2Se3 film with 75 nm thickness, contacted by two Au striplines. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Figure 1c shows an image of a Bi2Se3 film with two gold striplines serving as electronic contacts. We scan the pump laser across such a Bi2Se3 film and record the time-integrated photocurrent Iphoto as a function of the laser position (Fig. 2a). At the metal interfaces (triangles), a photothermoelectric current is generated because of a laser-induced heat gradient and the large thermoelectric power of Bi2Se3. In between the two striplines, the time-integrated photocurrent averages to be close to zero (circles in Fig. 2a,b). Changing the polarization of the exciting laser from circularly left-handed to horizontally linear and then to circularly right-handed (Fig. 2c), we observe the sinusoidal fingerprint15 of a circular photogalvanic current with an amplitude C (Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1). The sinusoidal fits consider the circular and linear photogalvanic currents depending on the oblique angle θ=+17° (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The different background amplitudes of Iphoto are highlighted as dashed lines in Fig. 2c. They represent the spatially varying, dominant photothermoelectric current Ithermo. We introduce a fidelity f=C/(C+Ithermo), which describes the ability to resolve the circular photogalvanic current with respect to Ithermo. For all samples, we find f to be smaller than 40% in time-integrated measurements. The maximum value is achieved for the laser being positioned at the centre of the Bi2Se3 film (for example, circles in Fig. 2), where the overall Ithermo generated within the laser spot averages out towards the noise amplitude (Ithermo→Anoise~40 pA). As we show below, high-speed, time-resolved measurements provide a fidelity close to unity. This high fidelity can be achieved because photocurrent contributions on different timescales with different directions do not average out.

(a) Photocurrent map of Iphoto in colour scale. Dotted lines indicate the position of the striplines. Scale bar, 5 μm. (b) Line scan along the black dashed dotted line in (a) with a positive (rightward triangle) and a negative peak (leftward triangle) close to the striplines. Circle denotes position of zero signal of Iphoto. (c) Polarization dependence of Iphoto. Positions are denoted in (a,b). The symbol denotes linearly polarized (along the x-axis), circularly right-handed polarized and circularly left-handed polarized photons. The background contributions Ithermo are denoted by dashed lines as described in Methods. Experimental parameters: 75-nm-thin Bi2Se3 film, Ephoton=1.53 eV, Plaser=20 mW and Tbath=295 K.

Photothermoelectric currents at the contacts

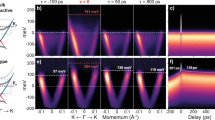

We measure the time-resolved photocurrent Isampling for different excitation positions on a Bi2Se3 film from the right to the left contact (right- and leftward triangles in Fig. 3a). For all positions, we observe that Isampling changes sign and therefore direction at a certain Δt. This means that for short (long) times, a current with a direction towards the closer (farther) contact dominates. The origin of the opposing currents can be understood as follows. Within the first picosecond after excitation, the electrons thermalize to form a hot carrier ensemble27,28. They propagate away from the laser spot due to sample-internal potentials such as the thermopower and the density gradient. Close to the metal interfaces, the thermopower generated between Bi2Se3 and Au gives rise to the photothermoelectric current.

(a) Isampling for excitation positions across a Bi2Se3 film in steps of 3 μm. The leftward (rightward) triangle marks an excitation position at the left (right) metal contact. The circle highlights an excitation at the centre of the Bi2Se3 film. Solid lines are fits to the data. Data are offset for clarity. Experimental parameters: 150-nm-thin Bi2Se3 film, Ephoton=1.59 eV, Plaser=1 mW, Vsd=0 V, Tbath=77 K and a linear polarization. (b) Isampling for excitation position in the centre of the Bi2Se3 film for −1 V≤Vsd≤+1 V.

Space and voltage dependence of the time-resolved photocurrents

In a time-of-flight analysis, we determine the ultrafast transport currents with opposing directions for each laser position (Supplementary Figs 2 and 3). The analysis allows us to estimate the fastest time-of-flight velocity of photogenerated hot electrons to be ve=(5.7±1.5) × 105 ms−1 at room temperature (Supplementary Note 2), which agrees remarkably well with the group velocity of the Bi2Se3 at the given Fermi-energy29,30, as discussed below. In addition, we determine the decay time of the photocurrent signals to be (3.0±0.5) ps at room temperature, which is in agreement with the picosecond relaxation dynamics of hot electrons26,27.

In a next step, we focus the laser onto the centre of the Bi2Se3 film (Fig. 3b) where the time-integrated photocurrent is close to zero (for example, circle in Fig. 2a). At high bias, the data mimic the curves measured at zero bias at the right and left contacts (right- and leftward triangles in Fig. 3a). This means that at the centre in between the striplines (Fig. 3b), an externally applied Vsd gives rise to an additional drift of the photogenerated hot electrons. The polarity of the applied bias allows us to confirm that the dominating contribution stems from electrons and not holes (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 4). The similarity of the top and bottom traces in Fig. 3a,b suggests that for certain values of Vsd at the centre, the corresponding electrostatic potential has an equivalent impact on the hot electron dynamics as the thermopower at the metal interfaces. In turn, at the centre of the sample and for Vsd=0 V, the net field due to sample-internal potentials is zero. Particularly, the temporal tails of Isampling are close to zero for Δt≥10 ps at zero bias. We note that there is always an ultrafast photocurrent within the first picoseconds at this position (Fig. 3b).

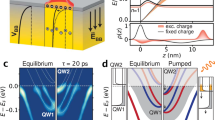

Helicity-dependent ultrafast photocurrents

Peculiarly, the sign and amplitude of the prevailing ultrafast contribution are completely controlled by the polarization of the exciting photons and their oblique angle of incidence. Figure 4a shows Isampling(Δt) measured close to the centre of another Bi2Se3 film for a varying photon polarization. The fitting curves consider ultrafast transport currents with changing directions depending on the photon polarization (Supplementary Fig. 2). Particularly, for Δt≈4 ps, the current amplitude depends only on the photon polarization. Microscopically, the helicity-dependent contribution results from an asymmetric excitation in k-space of the spin-polarized surface states caused by the peculiar helical symmetry of the surface states (Supplementary Fig. 1). The panels in Fig. 4a sketch the direction of the helicity-dependent current for circularly left-handed and right-handed polarized light (red and blue). The corresponding, measured peak amplitude follows the sinusoidal fingerprint of the circular and linear photogalvanic effects (Fig. 4b) with a fidelity f exceeding 95% for all temperatures. At the same excitation position, when the polarization dependence is measured in a time-integrated manner (Fig. 4c), the time-averaged background reduces f to be 32.6%, because the photocurrent contributions with different directions compete on long timescales.

(a) Isampling for excitation position close to the centre of a Bi2Se3 film for varying polarization. The laser is focused at a position at the centre of the Bi2Se3 film where the time-integrated photocurrent Iphoto is close to zero. Solid lines are fits to the data. Data are offset for clarity. Red and blue peaks are polarization-controlled ultrafast currents in the direction of ky to the right contact (red) or -ky to the left contact (blue) with an in-plane spin polarization (middle panel). (b) Fitted amplitude of Isampling for Δt=4 ps in (a) versus photon polarization. Error bars are fitting errors. (c) Simultaneously measured time-averaged Iphoto versus photon polarization. Experimental parameters: 90-nm-thin Bi2Se3 film, Ephoton=1.53 eV, Plaser=20 mW and Tbath=295 K.

Discussion

It is insightful to highlight the dynamics of the photocurrents in Fig. 4a again. After the spin depolarization and intraband cooling (Δt≥5 ps), the spin information and helicity protection are predominantly lost. Then, the expansion dynamics of the same (hot) electrons dominates the transport dynamics. These currents follow the combined influence of the thermopower and the electrostatic potentials. In the following, we will derive further insights into the interplay of the two potentials. Starting point is the fact that the optoelectronic expansion dynamics are dominated by photogenerated hot electrons that propagate at ve=(5.7±1.5) × 105 ms−1 (Supplementary Note 2). Generally, the dispersion of the surface states can be written as31

with ℏk the in-plane crystal momentum, vDirac is group velocity close to the Dirac point, D=−12.4 eV Å2 a quadratic term resulting from the broken particle-hole symmetry32, B=0 eV Å2 describing massive states32 and Δ the energy gap for the inter-surface coupling, which is zero for the investigated samples. The value for the binding energy of the Dirac point E0=(0.55±0.05) eV is determined from Hall-measurements (assuming an effective mass of 0.13·me)33. Recent photoemission experiments on n-type Bi2Se3 and related topological materials demonstrate that, only a few 100 fs after photoexcitation, the electron distribution is already centred at the Fermi-energy25,27,28. From equation (1), we derive the group velocity  to be (5.5±0.2) × 105 ms−1 at the Fermi-energy EFermi. We note that for bulk states, the principal order of the group velocity is in agreement with this value at the given Fermi-energy32. Importantly, the experimental value of ve agrees remarkably well with the derived value and with the reported one determined from photoemission experiments29,30. All values exceed the saturation drift velocity as measured in Bi2Se3-based transistor devices34. In other words, the group velocity of photogenerated charge carriers determines the ultimate speed of the optoelectronic response in topological insulators.

to be (5.5±0.2) × 105 ms−1 at the Fermi-energy EFermi. We note that for bulk states, the principal order of the group velocity is in agreement with this value at the given Fermi-energy32. Importantly, the experimental value of ve agrees remarkably well with the derived value and with the reported one determined from photoemission experiments29,30. All values exceed the saturation drift velocity as measured in Bi2Se3-based transistor devices34. In other words, the group velocity of photogenerated charge carriers determines the ultimate speed of the optoelectronic response in topological insulators.

Experimentally, this manifests itself in a linear time-of-flight diagram with ve=(5.7±1.5) × 105 ms−1 (Supplementary Figs 2 and 3). To further discuss this surprising result, we use a two-temperature model Te and Tphonon for the electron and phonon baths35,36. The electron heat capacity is well approximated by a linear temperature dependence Ce~C′eTe, if Te≪TFermi with TFermi=3,320 K the Fermi-temperature of the measured n-type Bi2Se3 films37. Within this model, we calculate the maximum electron temperature Temax=1,500 K for the experimental parameters as in Fig. 3a (ref. 35). The electron–electron collision time can be estimated to be τee~ℏEFermi/(kBTe)2=9 fs, with kB the Boltzmann constant37, and the electron-phonon scattering time is on the order of τe-phonon~ℏ/(kBTbath)=94 fs. The latter was recently determined to be ~0.7 ps for optical phonons and ~2.3 ps for acoustic phonons24,27. In this regime (τee≪τe-phonon), there exists a strong electron-lattice non-equilibrium, and the electron relaxation is governed by the electron–electron collisions35. It was reported that, hereby, the electronic heat transport occurs at the Fermi velocity after an ultrafast optical excitation of the electron bath36. The dynamics can be analytically described by a two-temperature model in the limit of a strong electron-lattice non-equilibrium in combination with an electron heat conductance κe∝(Te)−1 (ref. 35). In the present experiment on Bi2Se3 films, the ultrafast current of hot electrons is measured. In our interpretation, this current carries the electronic heat to the contacts, and the corresponding heat transport at the Fermi velocity explains our data with linear time-of-flight diagrams (Supplementary Figs 2 and 3).

Our on-chip, time-domain THz spectroscopy allows us to reveal the impact of an electrostatic potential on such non-equilibrium expansion dynamics (Fig. 3b). Along this line, we estimate the maximum gradient of the local electron temperature profile to be ∇Temax~Temax/(0.5dstripline)=1,500 K/(0.5 × 15 μm)=200 K μm−1, with dstripline the distance between the two striplines. In first approximation, the measured expansion dynamics of the hot electrons are identical for exciting the Bi2Se3 films at the contacts (top and bottom traces in Fig. 3a) and for an excitation spot in the centre of the sample at finite bias (top and bottom traces in Fig. 3b). For the results in Fig. 3b, the laser position is carefully chosen such that influence of the thermopower induced at the contacts is close to zero. Then for a finite bias Vsd, the electrostatic potential gradient ∇Velectrostatic at the laser spot has an equivalent impact on the hot electron dynamics as the thermopower at the metal interfaces. We describe this thermopower at very short timescales as the product of SBi2Se3·∇ Te, with SBi2Se3 a non-equilibrium, effective Seebeck coefficient. Comparing the amplitudes of the top and bottom traces of Fig. 3a,b, we extract |∇Velectrostatic|=(820±440) V m−1 (Methods). In turn, we can estimate the effective Seebeck coefficient to be in the order of SBi2Se3minimum~∇Velectrostatic/∇ Temax=−(4.1±2.2) μV K−1. The extracted value phenomenologically describes the non-equilibrium thermopower at the Bi2Se3-metal contacts. To the best of our knowledge, the above derivation is the first estimate of an effective Seebeck coefficient of non-equilibrium hot electron ensembles after a pulsed laser excitation. The derived non-equilibrium Seebeck coefficient is smaller than the typical quasi-equilibrium value S~−50 μV K−1 (ref. 38). This can be understood as follows: for the experimental parameters in Fig. 3, we concurrently find a time-averaged amplitude |Iphoto|=370 pA at the Bi2Se3-metal contact and at an acquisition time of ~ms. At this long timescale, the heat transport is governed by phonons. Accordingly, we numerically calculate a temperature increase at a Bi2Se3-metal contact of ΔT=47 mK (for both the phonon and electron baths). In turn, we derive a quasi-static Seebeck coefficient by the following expression ΔV~SBi2Se3quasistatic ·ΔT, with SBi2Se3quasistatic=−23 μV K−1. For the sample and experimental conditions as in Fig. 2, we calculate SBi2Se3quasistatic=−62 μV K−1 at room temperature. Both values are consistent with the above quasi-equilibrium value of the Seebeck coefficient. In other words, at long timescales, the heat transport is dominated by phonons. However, at ultrashort timescales, it is governed by a highly non-equilibrium expansion of hot electrons. In our interpretation, this non-equilibrium current of hot electrons carries the electronic heat to the contacts as long as there exists a strong electron-lattice non-equilibrium as discussed above.

Intriguingly, despite of such high-speed dynamics of the hot electrons, the data at Δt~4 ps in Fig. 4a demonstrate that the helicity-dependent currents can be still addressed and read-out. The underlying physical reason is the protection of the helical states within the spin depolarization time. Only for Δt≥5 ps in Fig. 4a, all currents have the same negative sign. That means that, for this particular experiment, still a tiny thermopower potential drives these currents to the left contact, which is consistent with the negative offset observed in the time-integrated measurement (Fig. 4c). Again, for Δt≥5 ps, there is no polarization control for these currents anymore, since the pump-laser pulse is off and the spin depolarization has occurred (Fig. 4a).

The circular and linear photogalvanic effects are induced via surface states and not bulk states because of the broken inversion symmetry at the surface of Bi2Se3 (refs 15, 17). A normal incidence geometry (θ=0°) suppresses the photogalvanic effects (Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating an in-plane spin distribution and more fundamentally, an in-plane rotational symmetry of the involved electron states in Bi2Se3. Generally, there may be a small contribution from a helicity-independent transverse photon drag effect17. Contributions from Rashba-split bulk states at a surface inversion layer can be assumed to be negligible for the examined range of Ephoton (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 5). Overall, the ultrafast polarization-controlled photocurrent is limited by the spin lifetime in Bi2Se3.

To conclude, our experiments demonstrate the temporal separation of helicity-dependent surface photocurrents from polarization-independent bulk currents even at room temperature, and they reveal the onset of photothermoelectric currents at ultrafast timescales. We elaborate the connection between the non-equilibrium currents of hot electrons directly after the pulsed laser excitation and the time-averaged thermoelectric currents, which are typically described in the framework of a Seebeck coefficient. A time-of-flight analysis yields a speed of the photogenerated electrons that is consistent with the group velocity at the Fermi-energy of the Bi2Se3. Our results significantly advance the understanding of the optical excitation scheme and the ultrafast photocurrent dynamics in topological insulators. The time-delayed photothermoelectric currents in Bi2Se3 are partly caused by the n-doping of the material. They can be reduced by utilizing topological insulators with a Fermi-energy in the Dirac cone, such as Bi2Te2Se or (Bi1-xSbx)2Te3 (refs 7, 8). The picosecond response time of the surface currents proves the anticipated potential of topological insulators as promising materials for high-speed optoelectronic applications from the THz to the infrared range.

Methods

Fabrication of the Bi2Se3 films

The investigated Bi2Se3 films have a thickness of 50 nm≤250 nm and a lateral dimension of >15 μm. We produce the Bi2Se3 films from 99.999% pure crystalline Bi2Se3 granulate via exfoliation. We analyse the homogeneity and the dimensions of the films using optical microscopy, atomic force microscopy and white light interferometry. The presented results have been reproduced on three independent samples, which have a thickness of 75, 90 and 150 nm. Hall-measurements on a 65-nm-thin Bi2Se3 film from the same batch yield an electron density of ~4·1019 cm−3 at room temperature.

Design of the stripline circuit

Starting point is a 430-μm-thick sapphire substrate covered with a 300-nm-thin layer of ion-implanted silicon (Si). In a first optical lithography step, the Auston-switch geometry is formed via HF etching. The remaining silicon strip serves as a field probe (Auston-switch). Bi2Se3 films are mechanically transferred onto the substrate by exfoliation. In a second optical lithography step, we evaporate 10 nm titanium (Ti) and 110–200 nm gold (Au) to form the waveguide circuits contacting the Bi2Se3 films and the read-out of the Auston-switch. The distance between two parallel striplines is 15 μm. Each stripline itself has an individual width of 5 μm. The Bi2Se3 films are placed at a typical distance of 100 μm≤800 μm from the Auston-switch. The bias voltage Vsd is applied between striplines (see Fig. 1). The striplines including the Bi2Se3 films have a two-terminal resistance of 2.9 kΩ, while the Bi2Se3 films have a resistance of ~55 Ω. Hereby, the gradient ∇Velectrostatic can be estimated from the bias voltage via ∇Velectrostatic=Vsd/15 μm · 55 Ω/2.9 kΩ.

Time-integrated photocurrent spectroscopy

The time-averaged Iphoto is measured in between the two striplines (Fig. 1b) with a current-voltage amplifier.

On chip time-domain THz photocurrent spectroscopy

The Bi2Se3 films in the stripline circuit are optically excited by a pump pulse with ~200 fs pulse length generated by a titanium:sapphire laser at a repetition frequency of ~76 MHz with a photon energy of Ephoton=1.53 eV and Ephoton=1.59 eV. After excitation, an electromagnetic pulse starts to travel along the striplines. A field probe senses the transient electric field of the travelling pulse (Fig. 1b). Here we utilize an Auston-switch based on ion-implanted silicon. At a time delay Δt with respect to the pump pulse, the Auston-switch is short-circuit by a probe pulse for the duration of the lifetime of the photogenerated charge carriers in the silicon (τ≤ 1 ps). During this time period, the transient electric field present at the field probe drives the current Isampling. In turn, measuring Isampling(Δt) yields information on the optoelectronic response of the Bi2Se3 with a picosecond time-resolution. The time a THz-pulse travels from the Bi2Se3 film to the field probe can be estimated via ttravel=d· nsapphire/c=0.5 mm · 3.07/c~5.1 ps for a distance of 0.5 mm between the Bi2Se3 film and the Auston-switch. The striplines have a total length exceeding 48 mm. Thus, reflections at the end of the striplines are expected for Δt≥490 ps. These reflections are strongly reduced due to damping and radiation losses. Therefore, no reflections overlap with the electromagnetic signal coming directly from the Bi2Se3 films in our data. The data of Figs 2 and 4 are presented for room temperature. The time-of-flight data in Fig. 3 are depicted for 77 K, because the transfer characteristics of the striplines and therefore the signal-to-noise ratio are enhanced at lower temperatures. A time-of-flight analysis of data at room temperature is presented in the Supplementary Fig. 3. The position of the pump-spot is set with a spatial resolution of ~100 nm, while the position of the probe-spot is kept constant throughout the experiments. All measurements of Isampling were carried out utilizing an optical chopper system, a current-voltage converter connected to the field probe and a lock-in amplifier. The spot size (FWHM) of the pump-laser is 3–4 μm for all time-resolved experiments and up to 9 μm for the time-integrated experiments. The laser power of the pump (probe) pulse is chosen to be in the range of 0.1–20 mW (80–150 mW). All data are taken in vacuum (~10−5 mbar) to prevent the effect of photo-desorption of oxygen on the surface of the Bi2Se3. The measurements have been reproduced for different temperatures between 4 and 295 K.

Polarization control and sinusoidal fitting function

The polarization-dependent photocurrents are characterized by measuring Iphoto or Isampling, while rotating a λ/4-waveplate by an angle φ. The rotation changes the photon polarization with a period of 180° from linearly polarized (φ=0°) to left-handed circular (φ=45°), to linearly (φ=90°), to right-handed circular (φ=135°) and to linearly (φ=180°). The fitting curves in Figs 2c and 4b,c describe the photocurrent in the y-direction of the Bi2Se3 films (Fig. 1b) as j(φ)=C sin 2φ+L1 sin 4φ+L2 cos 4φ+D. As recently demonstrated15, C describes the helicity-dependent circular photogalvanic effect with a rotational in-plane symmetry in Bi2Se3. L1 comprises the helicity-independent linear photogalvanic effect. L2 and D are bulk contributions (Supplementary Note 1).

Additional information

How to cite this article: Kastl, C. et al. Ultrafast helicity control of surface currents in topological insulators with near-unity fidelity. Nat. Commun. 6:6617 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7617 (2015).

References

Chen, Y. L. et al. Experimental realization of a three-dimensional topological insulator, Bi2Te3 . Science 325, 178–181 (2009) .

Hsieh, D. et al. A tunable topological insulator in the spin helical Dirac transport regime. Nature 460, 1101–1105 (2009) .

Seo, J. et al. Transmission of topological surface states through surface barriers. Nature 466, 343–346 (2010) .

Li, C. H. et al. Electrical detection of charge-current-induced spin polarization due to spin momentum locking in Bi2Se3 . Nat. Nano 9, 218–224 (2014) .

Kim, D. et al. Surface conduction of topological Dirac electrons in bulk insulating Bi2Se3 . Nat. Phys. 8, 460–464 (2012) .

Chen, J. et al. Gate-voltage control of chemical potential and weak antilocalization in Bi2Se3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 176602 (2010) .

Gehring, P., Gao, B. F., Burghard, M. & Kern, K. Growth of high-mobility Bi2Te2Se nanoplatelets on hBN sheets by van der Waals epitaxy. Nano Lett. 12, 5137 (2012) .

He, X. et al. Highly tunable electron transport in epitaxial topological insulator (Bi1-xSbx)2Te3 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 123111 (2012) .

Zhang, X. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators for high-performance terahertz to infrared applications. Phys. Rev. B 82, 245107 (2010) .

Fu, L., Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Topological insulators in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 106803 (2007) .

Hasan, M. & Kane, C. Colloquium: topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010) .

Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011) .

Raghu, S., Chung, S. B., Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Collective modes of a helical liquid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 116401 (2010) .

Jozwiak, C. et al. Photoelectron spin-flipping and texture manipulation in a topological insulator. Nat. Phys. 9, 293–298 (2013) .

McIver, J. W., Hsieh, D., Steinberg, H., Jarillo-Herrero, P. & Gedik, N. Control over topological insulator photocurrents with light polarization. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 96–100 (2012) .

Kastl, C. et al. Local photocurrent generation in thin films of the topological insulator Bi2Se3 . Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 251110 (2012) .

Ganichev, S. D. & Prettl, W. Spin photocurrents in quantum wells. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 15, R935–R983 (2003) .

Hosur, P. Circular photogalvanic effect on topological insulator surfaces: Berry-curvature-dependent response. Phys. Rev. B 83, 035309 (2011) .

Junck, A., Refael, G. & Von Oppen, F. Photocurrent response of topological insulator surface states. Phys. Rev. B 88, 075144 (2013) .

Prechtel, L. et al. Time-resolved ultrafast photocurrents and terahertz generation in freely suspended graphene. Nat. Commun. 3, 646 (2012) .

Erhard, N. et al. Ultrafast photocurrents and THz generation in single InAs-nanowires. Ann. Phys. 525, 180–188 (2013) .

Auston, D. Impulse response of photoconductors in transmission lines. Quantum Electron. IEEE J. 19, 639–648 (1983) .

Wang, Y. H. et al. Observation of a warped helical spin texture in Bi2Se3 from circular dichroism angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 207602 (2011) .

Hsieh, D. et al. Selective probing of photoinduced charge and spin dynamics in the bulk and surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 077401 (2011) .

Hajlaoui, M. et al. Ultrafast surface carrier dynamics in the topological insulator Bi2Te3 . Nano Lett. 12, 3532–3536 (2012) .

Wang, Y. et al. Measurement of intrinsic Dirac fermion cooling on the surface of the topological insulator Bi2S3 using time-resolved and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 127401 (2012) .

Crepaldi, A. et al. Ultrafast photodoping and effective Fermi-Dirac distribution of the Dirac particles in Bi2Se3 . Phys. Rev. B 86, 205133 (2012) .

Hajlaoui, M. et al. Tuning a Schottky barrier in a photoexcited topological insulator with transient Dirac cone electron-hole asymmetry. Nat. Commun. 5, 3003 (2014) .

Kuroda, K. et al. Hexagonally Deformed Fermi Surface of the 3D Topological Insulator Bi2Se3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 076802 (2010) .

Sobota, J. A. et al. Direct optical coupling to an unoccupied Dirac surface state in the topological insulator Bi2Se3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 136802 (2013) .

Lu, H.-Z. et al. Massive Dirac fermions and spin physics in an ultrathin film of topological insulator. Phys. Rev. B 81, 115407 (2010) .

Berntsen, M. H. et al. Direct observation of decoupled Dirac states at the interface between topological and normal insulators. Phys. Rev. B 88, 195132 (2013) .

Analytis, J. G. et al. Bulk Fermi surface coexistence with Dirac surface state in Bi2Se3: A comparison of photoemission and Shubnikov–de Haas measurements. Phys. Rev. B 81, 205407 (2010) .

Zhu, H. et al. Topological insulator Bi2Se3 nanowire high performance field-effect transistors. Sci. Rep. 3, 1757 (2013) .

Kanavin, A., Smetanin, I. & Isakov, V. Heat transport in metals irradiated by ultrashort laser pulses. Phys. Rev. B 57, 14698 (1998) .

Brorson, S. D., Fujimoto, J. G. & Ippen, E. P. Femtosecond electronic heat-transport dynamics in thin gold films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 1962 (1987) .

Abrikosov, A. A. Fundamentals of the Theory of Metals North-Holland (1988) .

Stordeur, M. et al. Optical and electrical investigations of n‐Type Bi2Se3 Single Crystals. Phys. Status Solidi B 169, 505–514 (1992) .

Acknowledgements

We thank Leonid Levitov and Michael Knap for insightful discussions, as well as Andreas Brenneis and Ursula Wurstbauer for technical assistance. This work was supported by the DFG via SPP 1666 (grant HO 3324/8), ERC Grant NanoREAL (n°306754), the DFG excellence cluster ‘Nanosystems initiative Munich (NIM)’, the ‘Center of NanoScience (CeNS)’ in Munich and the Munich Quantum Center (MQC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C. Kastl and C. Karnetzky performed the experiments and analysed the data together with A.W.H. A.W.H., C. Kastl and C. Karnetzky conceived the study and co-wrote the paper with H.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-5, Supplementary Notes 1-3, and Supplementary References (PDF 332 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kastl, C., Karnetzky, C., Karl, H. et al. Ultrafast helicity control of surface currents in topological insulators with near-unity fidelity. Nat Commun 6, 6617 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7617

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7617

This article is cited by

-

A candidate material EuSn2As2-based terahertz direct detection and imaging

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2022)

-

Observation of a giant mass enhancement in the ultrafast electron dynamics of a topological semimetal

Communications Physics (2021)

-

Josephson current mediated by ballistic topological states in Bi2Te2.3Se0.7 single nanocrystals

Communications Materials (2020)

-

Deep tuning of photo-thermoelectricity in topological surface states

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Scattering symmetry-breaking induced spin photocurrent from out-of-plane spin texture in a 3D topological insulator

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.