Abstract

Dendrite growth threatens the safety of batteries by piercing the ion-transporting separators between the cathode and anode. Finding a dendrite-suppressing material that combines high modulus and high ionic conductance has long been considered a major technological and materials science challenge. Here we demonstrate that these properties can be attained in a composite made from Kevlar-derived aramid nanofibres assembled in a layer-by-layer manner with poly(ethylene oxide). Importantly, the porosity of the membranes is smaller than the growth area of the dendrites so that aramid nanofibres eliminate ‘weak links’ where the dendrites pierce the membranes. The aramid nanofibre network suppresses poly(ethylene oxide) crystallization detrimental for ion transport, giving a composite that exhibits high modulus, ionic conductivity, flexibility, ion flux rates and thermal stability. Successful suppression of hard copper dendrites by the composite ion conductor at extreme discharge conditions is demonstrated, thereby providing a new approach for the materials engineering of solid ion conductors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increasing the capacity and discharge rate of batteries represents the key bottleneck preventing the full realization of a number of technologies such as electrical vehicles, solar/wind energy conversion, flexible electronics and health monitoring devices. Much attention has been paid to maximizing the energy and power densities of cathodes and anodes of lithium batteries1,2, especially using new forms of nanostructured materials3,4 and thin polymer films4. Although many problems related to the stability of cathodes and anodes remain to be resolved, more attention needs to be paid to the ion-conducting membranes (ICMs) separating them. These membranes represent an equally crucial part of high capacity and high discharge rate batteries. The ICM is the key component responsible for safe operation of lithium ion and other batteries, which have been known to cause accidents in the past. Current ICMs are typically made from microporous polymer sheets impregnated with solutions of lithium salts in alkylcarbonates. These gel or liquid phases serve as the ion-conducting media enabling transport of ions but preventing transport of electrons between the electrodes. Shortcomings of such ICMs include flammability, fluid leakage, limited range in operating temperatures and sporadic internal shorting leading to battery fires. Materials adequately addressing these shortcomings are difficult to find because the properties required of ICMs impose seemingly contradictory requirements on the atomic structure of the ICM material. While lithium (or other) ions need to have high mobility to enable high ion conductivity (ΩICM), the remaining atomic framework needs to be rigid to give ICMs high stiffness (EICM) and shear modulus (GICM). Safe batteries would also require ICMs that are both flexible and tough. However, Ashby plots5 and other data6,7 indicate that tolerance to high local strains is difficult to combine with high strength and stiffness8; similar incompatibilities also exist with several other combinations of mechanical and transport properties of materials9. Moreover, as the charge rate and power density of the batteries increase, the importance of having a reliable insulating barrier between the electrodes also markedly increases. Besides having adequate mechanical and ion transport properties, we must also considerably improve temperature resilience of current ICMs because high ionic currents will inevitably result in higher energy dissipation in a smaller volume. De facto the new ICMs to be paired with new anodes and cathodes must combine the advantages of ion-conducting glasses10 and polymers11 in one material. Resolution of these challenges essentially equates to finding new approaches to the materials engineering of ICMs involving new processes to synthesize them as well as novel ICM components.

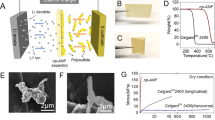

The safety problems of modern batteries are mainly related to dendrite growth and anode expansion in charged state12,13,14,15,16. Piercing of porous polymer separators, for instance Celgard 2400 (Fig. 1a), by dendrites (Fig. 1b) is the most common mechanism of spontaneous battery failure, which can also lead to short circuit and fire17. The growth of dendrites is also the key roadblock for the development of batteries with safe lithium metal anodes, which can approach the theoretical limit for lithium-based storage devices with respect to capacity, power and weight18,19.

(a) Top view scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of copper dendrite penetrating through Celgard ICM. (b) SEM image of the tip of a copper (right) and lithium (left) dendrite. (c) Transmission electron microscopy image of ANF. (d) Top and (e) side view SEM images of (PEO/ANF)200. (f) Optical photograph of (PEO/ANF)200.

Many different approaches have been previously proposed to prevent dendrite formation, including additives to the gel and liquid electrolyte or composite gel electrolytes with inorganic fillers20, however, the dendrite problem still persists in these cases. The variety of data suggests that improvement of the mechanical properties of the ICM such as EICM or GICM could markedly inhibit their growth.21 Sufficient compressive stress exerted on dendrite tips is expected to inhibit their growth22,23.

Multiple materials combinations and materials engineering approaches have been investigated in the past to make ICMs, but these presented problems of their own, eventually translating into alternative safety concerns and/or energy losses. Solid electrolytes based on Li-based ceramics represent one of the currently most advanced ion conductors available10,24,25. They combine high mechanical stiffness (E=80–100 GPa) and high ionic conductivity (ΩICM from 10−3 S cm−1 (refs 10, 24) to 1.2 × 10−2 S cm−1)25. These parameters make them exciting candidates for some high-power applications. However, as the industry is continuously pushing for higher energy density, the mechanical properties of internal components become essential as never before. Their brittleness of the Li-based ceramics, reflecting the fundamental conflict between the two essential materials properties6, makes it difficult to incorporate Li-based ceramics into battery packs. Their safety concerns associated with cracking of ceramic separators also necessitate thicker ICMs with increased internal resistance leading to energy losses. The issues related to mechanical properties of LIPON separators also plague the manufacturing of thin film batteries with lithium metal anodes for flexible electronics. Finding new versatile materials that make possible dendrite inhibition, and systematic studies of their dependence on different mechanical properties, is fundamentally important since dendrite growth is pervasive in virtually all electrochemical devices utilizing a range of metals and electrolytes.

Here we describe a new composite that combines the key properties required for ICMs and effectively suppresses the growth of dendrites. The resulting membranes also exhibit low Ohmic resistance and high mechanical flexibility, which are essential for battery safety. As a “building block” for the new ICM, we decided to use aramid nanofibres (ANFs), whose preparation was described recently26. The macro-scale version of ANFs is Kevlar, one of the paragons of mechanical performance. ANFs with a length of 1 μm and an average diameter of 5–10 nm (Fig. 1c) were made by dissolution of bulk Kevlar fibres in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) in the presence of KOH. Notably, the ANFs are insulating, differentiating them from many other ultrastrong metallic and semiconducting nanomaterials (nanotubes, nanowires…) that cannot be used for ICMs.

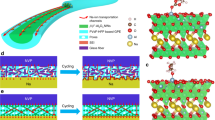

(a–d) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of bare physical vapour-deposited copper electrode with (a) no coating, (b) (PEO/ANF)10, (c) (PEO/ANF)30 and (d) (PEO/ANF)50 prior to dendrite growth. (e–l) SEM images of the same electrodes after copper dendrite growth with current density of 10.3 mA cm−2 on (e) bare copper electrode, copper electrode coated with (f) (PEO/ANF)10, (g) (PEO/ANF)30 and (h) (PEO/ANF)50. i–l are cross-sectional images of the same electrodes as in e–h, respectively. Total charge transferred=0.02 C cm−2.

Results

Material design and composite fabrication

ANFs were combined in this work with poly(ethyleneoxide) (PEO) serving as a solid ion-conducting media using the layer-by-layer (LBL) assembly method27. In the past, composites made by LBL or other methods have shown exceptional mechanical performance28 or ionic conductivity29,30, but not the combination of the two or any dendrite-suppressing capabilities. The ability of LBL to produce thin, uniform and nearly defect-free films is also of importance. Reduction of ICM thickness is needed to avoid high internal resistance inside the battery cells that leads both to heating, instability of operation and energy losses.

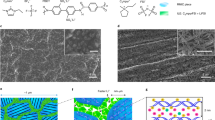

During the LBL process, the steady increase in the absorbance of the material at 330 nm indicates the linear growth of the (PEO/ANF)n film as the number of LBL deposition cycles, n, increases (Supplementary Fig. 1). Free-standing LBL multilayers were obtained by chemical delamination of (PEO/ANF)n films (Supplementary Fig. 2) after depositing 10–200 bilayers. Their smoothness, transparency and interference coloration (rainbows) indicated their uniform thickness and structural homogeneity, which can be also seen in scanning electron microscopy images (Fig. 1d–f). Atomic force microscopy images of (PEO/ANF)5 display a dense and uniform interconnecting network of thin nanoscale fibres (Supplementary Fig. 3). Such morphology provides the structural prerequisites for high ion conductance, stiffness and efficient distribution of local strains. The ultimate tensile strength, Young’s modulus and shear modulus were σICM=170±5 MPa, EICM=5.0±0.05 GPa and GICM=1.8±0.06 GPa, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4). Given PEO’s value of EICM=100 MPa, (PEO/ANF)n nanocomposites show an ~500 × increase in the elastic modulus. The impregnation with lithium triflate (often used in Li batteries as electrolyte) did not change the mechanical properties of the (PEO/ANF)200 composite.

Ionic conductivity

Crystallization of PEO is known to markedly decrease the ionic conductivity of ICMs made by traditional casting or blending11,31. However, in the (PEO/ANF)n composite we do not observe crystalline phase even though the polymer is deposited at room temperature, with and without lithium triflate, before and after soaking in electrolyte. Under these conditions, PEO crystallization should spontaneously occur but for (PEO/ANF)n composite crystallization is hindered due to LBL deposition and presence of the nanofibres. The amorphous nature of PEO in (PEO/ANF)n was confirmed by X-ray diffraction, which displayed a diffuse broad band for 2θ between 20° and 30° instead of the sharp peaks at 2θ=19° and 2θ=23° observed in crystalline PEO (Supplementary Fig. 5). Differential scanning calorimetry data (DSC) also support this conclusion (Fig. 3c). Neat PEO shows a sharp endothermic peak ~70 °C corresponding to the melting of the crystalline polymer, which is completely absent in the DSC curve for (PEO/ANF)n (Fig. 3c). In Fourier transform infrared spectra of the composite, we observed a strong peak at 2,860 cm–1 (Supplementary Fig. 6) assigned to intermolecular hydrogen bonds between PEO and ANF. These bonds are credited for the prevention of PEO crystallization as well as efficient LBL assembly32, which is consistent with the previous findings for PEO-based ion conductors31.

To investigate ionic conductivity, free-standing (PEO/ANF)n membranes were sandwiched between two lithium metal electrodes and housed in a CR2032 coin battery cell. Without any additives or additional treatments the ionic conductivities of (PEO/ANF)200 at 25 °C and 90 °C were ΩICM,25°C=5.0 × 10−6 S cm−1 and ΩICM,90 °C=2.6 × 10−5 S cm−1, respectively. The (PEO/ANF)200 membrane was immersed in a 1 M lithium triflate solution and 1 M lithium bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide solution in a propylene carbonate/dimethyl carbonate 1:1 v/v mixture, followed by overnight drying in a vacuum oven. The ionic conductivity of (PEO/ANF)200 was subsequently found to be 5.5 × 10−5 and 2.5 × 10−5 S cm−1, comparable to that of some Li sulfide glasses10,24. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy curves showed a depressed semicircle shape (Supplementary Fig. 7), which is typical among solid electrolytes20,25. No change in ICM thickness or other indications of swelling or conversely PEO crystallization as a result of salt intercalation31 was observed in this process. This salt intercalation step was needed to impregnate initial concentration of Li+ ions and to avoid initial ‘ramp up’ period.

To better replicate the actual battery conditions and mitigate contact resistance between the electrode and the solid (PEO/ANF)200 membranes, 150 μl of a 1M lithium hexafluorophosphate solution in an ethylene carbonate/dimethyl carbonate 1:1 v/v mixture was added to each side of the membrane as was used in other studies on compliant composite ICMs20. In this case the ionic conductivity of (PEO/ANF)200 reached ΩICM,25 °C=1.7 × 10−4 S cm−1. Note that this value reflects the low limit of ionic conductivity for (PEO/ANF)200 under actual operating conditions in a battery because the temperature between electrodes is higher than temperature in the environment outside.

Dendrite suppression

With respect to dendrite propagation, we have to point out that careful investigation of lithium dendrite growth and suppression is well known to be practically complicated due to high reactivity of lithium metal with ambient air and water. Moreover, the fast oxidation of Li metal changes the shape, length and mechanical properties of the dendrites, making the results inconclusive. Imaging of lithium dendrite growth using synchrotron-based X-ray tomography19 and electrochemical liquid transmission electron microscopy holders can potentially be applied for this system33, but we decided to look for a simpler method that can be applied consistently to ICMs for many different types of batteries with standard equipment base. Therefore we decided to carry out the study for copper dendrites, which can serve as convenient ‘mechanical’ proxy of lithium dendrites under ambient conditions. The results obtained for copper are relevant for lithium because the Young’s modulus of copper is E=129.8 GPa, while that for lithium is E=4.91 GPa. The theory of electrochemical dendrite growth34 indicates that if local mechanical properties of ICM are sufficient to prevent mechanical stress from dendrites from copper, it will also suppress dendrites from lithium, which are much softer. Notably, we do not claim that copper and lithium are electrochemically similar.

To experimentally design successful dendrite-suppressing ICMs, we need to consider the dimensions of dendrites and ion-conducting pores. In comparison, we observed that copper dendrites have growth zones with a size of 50–100 nm and tip diameter of 25 nm (Fig. 1b, right), and so do dendrites from lithium19. We have also observed that lithium dendrites are approximately twice the size copper dendrites (Fig. 1b, left), making copper dendrites suppressing more challenging than that of lithium while retaining the same fern-like shape. The similarity of shapes confirms the usefulness of copper dendrites as the mechanical proxy of lithium dendrites; the dendrite footprints on the membrane are virtually identical.

The dendrites propagate through ICMs via the path of least mechanical resistance. Importantly, typical polymeric ICMs are made as heterogeneous membranes to provide high ionic conductivities. Therefore, if a heterogeneous material has soft pores larger than ddendr, these parts with low modulus determine the propagation of dendrites rather than the stiffer parts. If the heterogeneity of an ICM is smaller than ddendr, the growth zone of the dendrite experiences a resistance equivalent to the averaged modulus of the membrane.

Many ICMs are strongly heterogeneous at scales much greater than ddendr. Celgard, for instance, is microscopically stiff with E=1.1 GPa and a tensile strength of 11.1 MPa, but it contains large pores of ion-conducting gel with sizes of ~430 nm (Fig. 1a). Consequently, the mechanical properties relevant to dendrite growth are those found in propylene carbonate and ethylene carbonate loaded with lithium salts. Being liquids, the electrolytes offer little to no resistance with regard to blocking dendrite growth.

The scale of inhomogeneity and dendrite inhibition in (PEO/ANF)n is very different. (PEO/ANF)n exists as a film of tightly interconnected PEO and ANF networks. Pores in the film are 20 nm in diameter (Fig. 1c,d) and are smaller than ddendr. Therefore, the growing dendrites will experience the component-averaged (macroscopic) stiffness of (PEO/ANF)n.

Investigation of dendrite growth was carried out under conditions of high current density (10.3 mA cm−2), which is equivalent to a 6–7-C charge/discharge rate. Under such conditions, one could fully charge a battery in <10 min, while the typical charging rate for batteries is ~0.25 C. Copper electrodes coated with (PEO/ANF)10, (PEO/ANF)30 and (PEO/ANF)50 were investigated by SEM (Fig. 2) after a total charge of Q=0.006 mAh cm−2 was transferred. Copper dendrites with an average size of 500 nm formed on the bare Cu electrode (Fig. 2a,e,i). Notably, the shape of dendrites was strikingly similar to those formed by lithium19.

The size of the dendrites was markedly reduced to 100–200 nm after depositing (PEO/ANF)10 (Fig. 2b,f,j), corresponding to a 162 nm coating on the electrode. Dendrite formation could no longer be detected for the electrode coated with (PEO/ANF)30 (Fig. 2c,g,k), which corresponds to a film thickness of 486 nm. The dendrites were reduced to an evenly deposited layer at the interface underneath the ICM, which is exactly what is needed for high performance safe anodes. Deposition of (PEO/ANF)50 films with a thickness of 809 nm results in complete inhibition of dendrite formation (Fig. 2d,h,l). We believe that (PEO/ANF)n films suppress the growth of dendritic deposits by exerting a compressive force on their growth points while being able to sustain the ionic flux through the membrane in accord with a previously elaborated theoretical mechanism22.

Thermal stability

Studies were conducted to comparatively investigate the thermal stability of (PEO/ANF)n nanocomposites. High-temperature stability of ICMs is needed to improve the safety of current lithium batteries at elevated temperatures, exemplified by the conditions under the hood of the car (120 °C) or in the case of a malfunctioning thermal management system. Higher temperature stability is a key parameter for high charge density, high discharge rate batteries35,36. In the hot solder iron test, a 180 °C solder iron tip was placed on both a PEO-ANF film and a Celgard 2400 polyethylene (PE) separator for 30 s. The Celgard 2400 PE was burned and a hole formed in it. In contrast, the PEO-ANF film showed no damage (Fig. 3a), which is in accordance with the high-temperature stability of parent Kevlar macrofibers being translated into ANFs. In the high-temperature oven test, both PEO-ANF and Celgard 2400 PE were kept at 200 °C for 10 min. The Celgard PE melted completely. The PEO-ANF remained flat, intact and un-deformed (Fig. 3b), indicating that high-temperature shrinkage and deformation are minimal for (PEO/ANF)n ICMs. Thermal stability of the PEO-ANF nanocomposite investigated by DSC and thermogravimetric analysis (Fig. 3c,d) demonstrated stability exceeding 400 °C, which is exceptional among polymeric ICMs and is, again, comparable to Li-based ceramics10.

Discussion

The breakthrough of combining high ionic conductance and the high modulus is illustrated in Fig. 4a, where the mechanical and electrochemical properties of current ICMs and (PEO/ANF)n is summarized. Detailed descriptions of the ICMs are listed in Supplementary Note 1. Commonly used separators such as Celgard monolayer polypropylene (PP), PE and trilayer PP/PE/PP have thickness ranging from 12 to 40 μm, and when infused with electrolyte give an internal resistance of RI=0.25 Ω. However, the large pores providing the conductive pathways also allow for the uninhibited growth of dendrites because of the softness of the containing gel. Polymeric electrolytes containing inorganic or organic fillers—solid ICMs that are most closely related to (PEO/ANF)n composites—are typically cast with a thickness ranging from 100 to 400 μm. They typically display RI values as high as 2,000 Ω. The high strength and ionic conductivity of (PEO/ANF)n makes possible substantial reduction of the thickness of ICMs and therefore a significant decrease of RI by 2–3 orders of magnitude. A 500 nm (PEO/ANF)30 ICM introduces RI=0.16 Ω into the CR2032 battery cell. The ANF-based composites are competitive in all respects with the best Li-based ceramics (Fig. 4a), while also retaining flexibility and toughness. Utilization of the high-strength insulating ANF and the nanoscale porosity of their networks in LBL films allowed us to combine the advantages of glass and polymeric ion conductors.

(a) Comparative evaluation of stiffness and internal resistance normalized to a standard CR2032 coin cell for (PEO/ANF)200 and other ICMs. The corresponding references and the list of abbreviations are given in Supplementary Table 1—BPAEDA, bisphenol A ethoxylate diacrylate; IL, ionic liquids; NBR, nitrile rubber; PAN, polyacrylonitrile; PEGDMA, poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate; PEGDME, poly(ethylene glycol)dimethyl ethers; PMMA, poly(methyl methacrylate); PSt, polystyrene; SN, succinonitrile. (b) Charge–discharge curve for the 30th, 40th and 50th cycle of a CR2032 button cell consisting of a LiCoO2 cathode, (PEO/ANF)200 with 30 μl 1 M LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate/dimethyl carbonate (EC/DMC), and a lithium metal anode at C/4 charge/discharge rate.

To substantiate the practicality of (PEO/ANF)n ICMs and their chemical stability in contact with lithium metal, we assembled a battery cell using (PEO/ANF)200, lithium metal anode and LiCoO2 cathode. The cell was studied over 50 cycles at C/4 (39 mA g−1, Fig. 4b). The battery exhibited a typical discharge capacity of over 130 mAh g−1 with a discharge efficiency as high as 98%. Although the battery parameters are limited by the stability of the LiCoO2 cathode and the charge transfer kinetics at both cathode and anode, complicating evaluation at extreme charge rates, this test demonstrates that a film as thin as 3 μm can perform at least as well as 25 μm thick layer of Celgard and prevent rapid deterioration of the battery due to lithium metal dendrite growth. Repeated acquisition of cyclic voltammograms of the cell (Supplementary Fig. 8) showed redox peaks at ~4.05 and 4.19 V typical for LiCoO2 cathode37 without the appearance of any new redox peaks confirming chemical stability from the PEO/ANF film.

(PEO/ANF)200 were also assembled into symmetric Li/separator/Li coin cells to further exemplify the suppression of lithium dendrites. Along with a control cell using Celgard 2400 as a separator, the cells are subjected to 0.25 mA cm−2 current density and the current direction is reversed every 30 min. Under these conditions stimulating the growth of dendrites, the control cell with Celgard 2400 showed a steady decrease in its voltage profile from the 1st cycle at 0.05 V to the 2,500th cycle at 0.02 V (Supplementary Fig. 9a), indicating a so called ‘soft short’ when ICM is slowly penetrated by lithium dendrites. As for the cell with (PEO/ANF)200, the voltage profile was maintained at 0.03 V starting from the 100th cycle to the 2,500th cycle (Supplementary Fig. 9b). The steady voltage profile for cells with (PEO/ANF)200 suggests that lithium dendrites are effectively suppressed.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that PEO and ANFs can be assembled into solid ICMs in which amorphous PEO produces ion-conducting channels smaller than ddendr. Consequently, (PEO/ANF)n composites with n=30–50 are capable of suppression of hard copper and soft lithium dendrites, while displaying ionic conductivity as high as 1.7 × 10−4 S cm−1. Resilience to harsh electrochemical and thermal conditions, as well as high flexibility and high ionic flux accompany the dendrite suppression capabilities, which is difficult to achieve in other classes of ion-conducting materials. Future studies related to metal crystallization under mechanical stress taking place under (PEO/ANF)n and dendrite suppression for other potential anode materials, such as sodium (E=10 GPa) and magnesium (E=45 GPa), are envisioned.

Methods

Preparation of (PEO/ANF)n nanocomposite ion conductors

Glass slides are pre-cleaned by piranha for 2 h followed by extensive rinsing with deionized (DI) water (18 MΩ) immediately prior to the LBL assembly. The glass slides are dipped in solutions of 0.01% PEO in DI water for 1 min, rinsed in DI water for 1 min, air dried and then dipped in a 0.04% ANF dispersion in DMSO for 10 s. The rinsing step after deposition of ANF consisted of a DMSO bath for 30 s followed by a 1 min rinse in DI water and air drying.

Growth of copper dendrites

Smooth copper layers 1-μm thick deposited on silicon wafers by physical vapour deposition are used as working electrodes. LBL membranes are then deposited onto the copper layer using the procedure described in Section 1. The copper–Si wafer electrode is dipped into a 0.15 M copper chloride solution in anhydrous DMSO with 1 cm2 of submerged surface area (Supplementary Fig. 10). About 10.3 mA cm−2 is applied to the electrode with a copper plate used as the counter electrode for 2 s. This corresponds to ~0.02 C cm−2 charge transferred. The sample was then rinsed gently with DMSO and dried under vacuum overnight at room temperature. The sample was then sputtered with gold in preparation for scanning electron microscopy. For cross-sectional images, the sample was broken in half to expose a cross-section after cooling with liquid nitrogen.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Tung, S.-O. et al. A dendrite-suppressing composite ion conductor from aramid nanofibers. Nat. Commun. 6:6152 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7152 (2015).

References

Scrosati, B. & Garche, J. Lithium batteries: Status, prospects and future. J. Power Sources 195, 2419–2430 (2010).

Su, D. S. & Schlögl, R. Nanostructured carbon and carbon nanocomposites for electrochemical energy storage applications. ChemSusChem 3, 136–168 (2010).

Milicev, Z., Burtovyy, R., Luzinov, I. & Yushin, G. A major constituent of brown algae for use in high-capacity Li-ion batteries. Science 7, 75–79 (2011).

Cebeci, F., Schmidt, D., Yang, S. H. & Hammond, P. Layer-by-layer assembled polyaniline nanofiber/multiwall carbon nanotube thin film electrodes for high-power and high-energy storage applications. ACS Nano 5, 8552–8561 (2011).

Wegst, U. G. & Ashby, M. F. The mechanical efficiency of natural materials. Philos. Mag. 84, 2167–2186 (2004).

Ritchie, R. O. The conflicts between strength and toughness. Nat. Mater. 10, 817–822 (2011).

Barthelat, F. Biomimetics for next generation materials. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 365, 2907–2919 (2007).

Keten, S., Xu, Z., Ihle, B. & Buehler, M. J. Nanoconfinement controls stiffness, strength and mechanical toughness of β-sheet crystals in silk. Nat. Mater. 9, 359–367 (2010).

Kim, Y. et al. Stretchable nanoparticle conductors with self-organized conductive pathways. Nature 500, 59–63 (2013).

Knauth, P. Inorganic solid Li ion conductors: an overview. Solid State Ion. 180, 911–916 (2009).

Agrawal, R. & Pandey, G. Solid polymer electrolytes: materials designing and all-solid-state battery applications: an overview. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 41, 223001 (2008).

Chan, C., Peng, H., Liu, G., McIlwrath, K. & Zhang, X. High-performance lithium battery anodes using silicon nanowires. Nat. Nanotech. 3, 31–35 (2007).

Bruce, P. G., Freunberger, S. A., Hardwick, L. J. & Tarascon, J. Li-O2 and Li-S batteries with high energy storage. Nat. Mater. 11, 19–29 (2012).

Tarascon, J. M. & Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 414, 359–367 (2001).

Goodenough, J. & Kim, Y. Challenges for rechargeable Li batteries. Chem. Mater. 22, 587–603 (2009).

Vetter, J., Novak, P., Wagner, M., Veit, C. & Möller, K. Ageing mechanisms in lithium-ion batteries. J. Power 147, 269–281 (2005).

Heller, A. The G. S. Yuasa-Boeing 787 Li-ion battery: test it at a low temperature and keep it warm in flight. J. Electrochem. Soc. 22, 35 (2013).

Armand, M. & Tarascon, J. M. Building better batteries. Nature 451, 652–657 (2008).

Harry, K. J., Hallinan, D. T., Parkinson, D. Y., MacDowell, A. A. & Balsara, N. P. Detection of subsurface structures underneath dendrites formed on cycled lithium metal electrodes. Nat. Mater. 13, 69–73 (2013).

Kim, S., Choi, K., Cho, S., Kil, E. & Lee, S. Mechanically compliant and lithium dendrite growth-suppressing composite polymer electrolytes for flexible lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 4949–4955 (2013).

Yamaki, J. et al. A consideration of the morphology of electrochemically deposited lithium in an organic electrolyte. J. Power Sources 74, 219–227 (1998).

Monroe, C. & Newman, J. The impact of elastic deformation on deposition kinetics at lithium/polymer interfaces. J. Electrochem. Soc. 152, A396–A404 (2005).

Stone, G. M. et al. Resolution of the modulus versus adhesion dilemma in solid polymer electrolytes for rechargeable lithium metal batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 159, A222–A227 (2012).

Minami, T., Hayashi, A. & Tatsumisago, M. Recent progress of glass and glass-ceramics as solid electrolytes for lithium secondary batteries. Solid State Ion. 177, 2715–2720 (2006).

Kamaya, N. et al. A lithium superionic conductor. Nat. Mater. 10, 682–686 (2011).

Yang, M. et al. Dispersions of aramid nanofibers: a new nanoscale building block. ACS Nano 5, 6945–6954 (2011).

Decher, G. Fuzzy nanoassemblies: toward layered polymeric multicomposites. Science 277, 1232–1237 (1997).

Shim, B. et al. Multiparameter structural optimization of single-walled carbon nanotube composites: toward record strength, stiffness, and toughness. ACS Nano 3, 1711–1722 (2009).

DeLongchamp, D. M. & Hammond, P. T. Fast ion conduction in layer-by-layer polymer films. Chem. Mater. 15, 1165–1173 (2003).

Tokuhisa, H., Lutkenhaus, J. & Hammond, P. Novel solid-state polymer electrolyte consisting of a porous layer-by-layer polyelectrolyte thin film and oligoethylene glycol. Langmuir 20, 9791–9795 (2004).

Christie, A. M., Lilley, S. J., Staunton, E., Andreev, Y. G. & Bruce, P. G. Increasing the conductivity of crystalline polymer electrolytes. Nature 433, 50–53 (2005).

Kharlampieva, E., Kozlovskaya, V. & Sukhishvili, S. A. Layer-by-layer hydrogen-bonded polymer films: from fundamentals to applications. Adv. Mater. 21, 3053–3065 (2009).

Holtz, M., Yu, Y., Gunceler, D. & Gao, J. Nanoscale imaging of lithium ion distribution during in situ operation of battery electrode and electrolyte. Nano. Lett. 14, 1453–1459 (2014).

Monroe, C. & Newman, J. Dendrite growth in lithium/polymer systems. J. Electrochem. Soc. 150, A1377–A1384 (2003).

Roth, E., Doughty, D. & Pile, D. Effects of separator breakdown on abuse response of 18650 Li-ion cells. J. Power Sources 174, 579–583 (2007).

Wang, Q. et al. Thermal runaway caused fire and explosion of lithium ion battery. J. Power Sources 208, 210–224 (2012).

Cho, J., Kim, Y. J. & Park, B. Novel LiCoO2 cathode material with Al2O3 coating for a Li ion cell. Chem. Mater. 12, 3788–3791 (2000).

Acknowledgements

S.H. thanks Professor Jeremy Lynch and Professor Levi Thompson for the help and support with ionic conductivity measurements. We are indebted to Professor C. Monroe for fruitful discussions. M.Y. would like to thank the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21303032), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2014M550184), Heilongjiang Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. LBH-Q13074), HIT Young Talent Program (Grant No. AUGA5710050613), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. HIT. IBRSEM. A. 201406).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A.K. conceived the project. S.-O.T., S.H., M.Y. and N.A.K. designed the experiments. S.-O.T., S.H., M.Y. and R.Z. fabricated the films, performed the experiments and analyzed the data. S.-O.T., S.H., and N.A.K. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

N.A.K and S.-O.T are consulting for Elegus Technologies, working on new battery development.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-10, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 830 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tung, SO., Ho, S., Yang, M. et al. A dendrite-suppressing composite ion conductor from aramid nanofibres. Nat Commun 6, 6152 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7152

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7152

This article is cited by

-

Transition metals for stabilizing lithium metal anode: advances and perspectives

Tungsten (2024)

-

Advanced Aramid Fibrous Materials: Fundamentals, Advances, and Beyond

Advanced Fiber Materials (2024)

-

Hierarchically structured bioinspired nanocomposites

Nature Materials (2023)

-

Multifactorial engineering of biomimetic membranes for batteries with multiple high-performance parameters

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Focus on the Electroplating Chemistry of Li Ions in Nonaqueous Liquid Electrolytes: Toward Stable Lithium Metal Batteries

Electrochemical Energy Reviews (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.