Abstract

Interplay among various collective electronic states such as charge density wave and superconductivity is of tremendous significance in low-dimensional electron systems. However, the atomistic and physical nature of the electronic structures underlying the interplay of exotic states, which is critical to clarifying its effect on remarkable properties of the electron systems, remains elusive, limiting our understanding of the superconducting mechanism. Here, we show evidence that an ordering of selenium and sulphur atoms surrounding tantalum within star-of-David clusters can boost superconductivity in a layered chalcogenide 1T-TaS2−xSex, which undergoes a superconducting transition in the nearly commensurate charge density wave phase. Advanced electron microscopy investigations reveal that such an ordered superstructure forms only in the x area, where the superconductivity manifests, and is destructible to the occurrence of the Mott metal–insulator transition. The present findings provide a novel dimension in understanding the relationship between lattice and electronic degrees of freedom.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coexistence, competition and collaboration of superconductivity with charge order or charge density wave (CDW) are a long-term unresolved problem in low-dimensional electron systems. While the conventional Peierls mechanism can offer explanations to the CDW order via the Fermi-surface nesting induced by electron–phonon coupling, electron correlation takes on practical significance as well in some circumstances1,2,3,4, complicating our efforts to develop a general knowledge of the phase diagram in the vicinity of CDW order. Layered transition–metal dichalcogenides (TMDs)5,6 serve as an ideal platform for probing the intricate interplay in that their intrinsic two-dimensional structure is susceptible to electronic instability. This effect is especially pronounced in 1T-TaS2, where its CDW phases are diverse (that is, nearly commensurate CDW (NCCDW) and commensurate CDW (CCDW) phases) and its CCDW phase is compatible to the Mott insulating phase due to the strong electron–phonon and electron–electron interactions7,8,9,10,11,12.

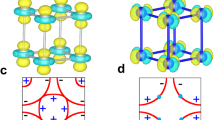

Current understanding of 1T-TaS2 and its associated phases, which is based mainly on electronic states, can be summarized in three aspects: (1) the CCDW phase of 1T-TaS2 can be attributed structurally to the fact that Ta atoms are displaced to form star-of-David clusters, wherein the 12 in-plane Ta atoms point towards a central Ta atom, interlocking each cluster to form a triangular superlattice7,8,13. However, the 12 electrons occupy the states below the distortion-induced gap and the thirteenth one dominates the states above the gap, resulting in a Mott insulating state that accounts for the high resistivity of the CCDW phase14,15,16, (2) the neighbouring NCCDW phase contains the star-of-David clusters as well albeit that they are less homogeneously arranged7, (3) with the rise of temperature, the Mott phase melts into the NCCDW phase with an extremely fast charge response and a sudden drop in resistivity, where several tens of stars organize into roughly hexagonal domains10,17. These reproduce locally the CCDW Mott phase, signifying that the CCDW mechanism is beyond the framework of the Peierls picture18,19,20,21,22. Definitely, none of them have supported a seemly counter-intuitive origin in understanding the low-dimensional quantum system, that is, the crucial role of atomic reconstruction due to the well-established concept: if electrons can move, atoms do not have to.

These considerations do not, however, exclude the ‘external’ feasibility that properties (for example, superconductivity) of 1T-TaS2 could be tuned by either chemical doping or external stimuli, thereby rendering it an ideal candidate for providing further insights into possible links between the collective electronic states in solids. Indeed, the superconductivity has been triggered in 1T-TaS2 by high pressure23, disordering24 and Fe and/or Se substitution (for example, 1T-TaS2−xSex)25,26,27,28,29. However, how electron correlation, CDW and superconductivity are correlated, and to what level the atomistic structure can play a role in understanding the origin of the superconducting (SC) nature in 1T-TaS2−xSex are still unknown. These points remain a mystery due to the difficulty in spatially resolving individual atomic columns in the two-dimensional SC materials, the challenge in chemically identifying Se atoms and the intricacy of establishing a link between atomic structure and SC in real materials.

In the following, combining the Cs-corrected high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF)30, annular bright-field (ABF)31 scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) with electric transport measurements, we provide evidence that superconductivity in 1T-TaS2−xSex (0≤x≤2.0) is characterized by an unexpected ordering of Se and S atoms within the star-of-David clusters. Such an atomically ordered superstructure may account for the emergence of superconductivity, perhaps opening up yet another useful avenue in tailoring superconductivity or even Mott metal–insulator transition via the atomistic ordering/disordering engineering.

Results

Crystal structure and electronic phase diagram

High-quality single crystals of 1T-TaS2−xSex (0≤x≤2.0) were grown by the chemical vapour transport technique, as identified by X-ray diffraction (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). Figure 1a–c shows sketches of its crystal structure and atomic planes, in which the central Ta is octahedrally coordinated by six S or Se atoms within the P-3m1 space group. One plane of the hexagonally arranged Ta atoms is sandwiched in between two planes of the hexagonally packed S or Se atoms via weak van der Waals interactions, while they are covalently bonded within the TMD sheets7. Figure 1d shows the electronic phase diagram as a function of temperature and x for 1T-TaS2−xSex, which uncovers a series of transitions in electronic states: (i) the Mott phase melts into the NCCDW phase, (ii) the superconductivity in a wide range of x develops into the NCCDW state and (iii) the CCDW phase revives eventually28. The superconductivity is isolated in between the CCDW Mott insulating phase and the isostructural CCDW metallic phase, implying a competition between superconductivity and the Mott metal–insulator transition. Moreover, the x dependence of SC transition temperature Tc follows a dome-like shape, which is fragile against the CCDW Mott transition driven by electron correlation12,21.

(a) Three-dimensional crystal structure of 1T-TaS2−xSex. (b,c) Distribution of Ta and S/Se atom in a 2 × 2 supercell along the a (b) and c (c) axes. (d) Electronic phase diagram of 1T-TaS2−xSex as a function of the temperature T and content x, which is derived from transport measurements. The CCDW, NCCDW and SC represent the commensurate CDW, nearly commensurate CDW and superconductivity, respectively. For the optimal SC sample with x=1.0, the SC transition temperature Tc is estimated to be 3.5 K.

Transport properties of 1T-TaS2−xSex

To track the evolution of electronic states, we present in-plane resistivity ρab as a function of temperature T for the 1T-TaS2−xSex (ref. 28), where a first-order transition from the NCCDW to the CCDW phase is discovered below 200 K. The CCDW transition shifts to a lower temperature with the rise of x, and the Mott insulating phase disappears completely for x>0.8. Interestingly, the superconductivity emerges in a wide range of x=0.9~1.6, above which it is suppressed at low temperatures, followed by an occurrence of a CCDW phase and metallicity until x=2.0. Evidently, the NCCDW transition shifts to higher temperature because the Se has a larger ionic radius than S. To further probe the SC states, the magnetic behaviour of 1T-TaSSe at 10 Oe is investigated by applying a magnetic field H parallel to the c axis28. Definitively, the diamagnetism signals turn up, indicating that there emerges superconductivity, consistent with the resistivity results. The Tc, which is defined as the onset in zero-field-cooled and field-cooled curves, is estimated to be ~3.5 K. Further, M(H) measurement reveals a lower critical field (Hc1~13 Oe) for the 1T-TaSSe, in line with the relationship −4πM=H, verifying the Meissner shielding effect as a representative type-II superconductor (Supplementary Fig. 2).

To shed light on the species of carriers in the 1T-TaS2−xSex, we measured thermoelectric power S as a function of temperature, as shown in Fig. 2a, where the sign of S is altered. The sign of S at room temperature S300 K switches from negative to positive as x increases (Fig. 2c), indicating that the majority of charge carriers are of hole type (p-type) for the Se-rich samples, while they are of electron type (n-type) for the S-rich samples. This also infers that more hole carriers can be activated at room temperature in the samples with a higher Se concentration. The Se 4p orbital may also be critical to producing conductivity in addition to the Ta 5d orbital, highlighting the importance of the p–d hybridization.

Formation of an ordered superstructure in SC 1T-TaSSe

We also obtain HAADF STEM images viewed along the c axis at room temperature for the samples involving the NCCDW phases (x=0, 0.5 and 0.8, in a close proximity to the CCDW Mott insulating phase) and the CCDW metallic phase (x=2.0) (Supplementary Fig. 3a–d). Since Tc in the SC region is extremely low (~3.5 K for x=1.0), here we focus on the higher temperature region especially for the NCCDW phase in that it appears in the proximity of the SC area (Fig. 1d). It should be noted that it is currently not possible to carry out STEM imaging at the extremely low temperature. Since intensity of an atomic column in a HAADF imaging mode is proportional to Z1.7 (Z is atomic number)32, the brighter spots represent the Ta columns (larger circles), whereas the darker ones represent the S/Se columns (smaller circles). Evidently, Ta atoms (marked by pink solid circles) are almost located at identical sites in all cases, forming the star-of-David clusters, where stars are interlocked by forming a triangular superlattice with a √13 × √13 periodicity7,8,13, in line with the crystal structure (Fig. 1a,c). Interestingly, only Ta atoms are visible in the HAADF image for x=0, whereas the S and Se atoms (yellow hollow circles) can also be identified for x=0.5, 0.8 and 2.0, indicating that the ordering of Se plays a critical role in enhancing the HAADF image contrast. The S and Se atoms are homogenously distributed in the x=0.5 and 0.8 cases, despite that the image contrast for x=0.8 is brighter than that for x=0.5. Unfortunately, the much lighter S atoms are not scattered strongly enough to be visualized, posing a significant hurdle to obtaining a complete structure in terms of the HAADF STEM interpretation alone. To directly resolve all atomic columns, we apply our newly developed ABF STEM imaging technique to observe 1T-TaS2−xSex, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3e–h. The ABF STEM method has been demonstrated to allow a simultaneous imaging of light and heavy atoms with a good signal-to-noise ratio, robustly over a range of sample thickness31. Apart from conveying the fundamental structural information as in the HAADF, the ABF STEM image, in which the dark spots represent atomic columns, identifies additional spots with weaker image contrast (yellow circles) as the S/Se columns, demonstrating the power of the ABF technique.

Surprisingly, an unexpected ordering of Se and S atoms occurs in the SC sample x=1.0, which shows an alternating alignment of brighter image contrasts for the Se-rich columns (yellow solid circles) and weaker ones for the S-rich columns (yellow hollow circles) in the star clusters (Fig. 3a), forming thereby an ordered superstructure at the atomic scale. Further ABF imaging uncovers an identical atomic structure (Fig. 3b), consolidating the ordering. Such S/Se ordering is supported by the selected-area diffraction pattern showing well-ordered secondary spots arising from the superstructure (Supplementary Fig. 4). We also obtain the image intensity line profile, as shown in Fig. 4, where one can see the S/Se ordering. Moreover, we also take the HAADF and ABF images along the orthogonal a axis, which allow us to reveal, for the first time, an atomic structure of TMD from the out-of-plane direction due to the technical complexities in making TEM samples (Supplementary Fig. 5). One can see a layered pattern, which comprises a brighter image contrast above the extremely bright Ta column (Se-rich column) and darker one below it (S-rich column), in further support of possible formation of an ordered superstructure. It is worthy of noting that the ordering takes place only in the x areas where the sample is SC, despite that the images are taken at room temperature, indicating that the ordered superstructure is related to the emergence of superconductivity.

(a,b) Atom-resolved HAADF (a) and ABF (b) STEM images seen from [0001] projection (c axis), revealing an ordered superstructure in 1T-TaSSe. It is noteworthy that intensity of Se-rich atomic columns (marked by yellow solid circles) is stronger than that of S-rich atomic columns (marked by yellow hollow circles). Scale bar, 1 nm.

(a) HAADF STEM image for 1T-TaSSe viewed from [0001] direction. Scale bar, 1 nm. (b,c) Line profiles showing the image intensity (a.u.) as a function of position in the image a along the b and c lines. The structural ordering can be clearly seen in the intensity line profile. The horizontal axis in b and c represents the distance along the lines marked in the ADF image, and the vertical axis in b and c represents the ADF image intensity (a.u.).

Since the Se/S ordering surrounding Ta atoms is solely observed in the vicinity of the SC phase, it represents a characteristic of the NCCDW phase, which is supported by an inherent electron pocket at the Brillouin-zone centre created by the band backfolding owing to the superlattice potential of NCCDW29. We have also surveyed the electronic states near the Fermi level (EF) in the NCCDW phase, and found a strong angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy intensity around the Γ point only29, revealing that the electron pocket at Γ point dominates the transport properties of the NCCDW phase.

Discussion

To gain more insights into correlation between CDW, superconductivity and atomistic structure, we present a schematic band diagram in Supplementary Fig. 6. From the band picture of the NCCDW and CCDW metallic phases (Supplementary Fig. 6a), one can see a NCCDW gap (ENCCDW) and a narrow band in it, which is pinned at EF around Γ point for S-rich samples. However, the embedded band at EF, which comes from the Ta 5d orbital in the NCCDW phase, eventually evolves to a robust electron pocket for the SC samples (Supplementary Fig. 6a). For the Se-rich samples, a Mott gap (EMott), which is triggered by the electron–electron interactions and stems from the Ta 5d orbital, turns up in the CCDW metallic phase, whereas a finite angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy intensity survives near EF29, which stems from the Se 4p orbital, suggesting that the orbital-selective Mott transition occurs. The orbital-selective Mott transition accounts for the localized Ta 5d and the itinerant Se 4p electrons: the Ta 5d orbital undergoes a Mott transition, while the Se 4p orbital is responsible for the unconventional metallic phase. On the other hand, from the viewpoint of orbital character, for S-rich samples, the S 3p or Se 4p orbital is far away from the Ta 5d orbital, limiting the p–d hybridization. For SC samples, the Se 4p orbital shifts to EF and overlaps Ta 5d orbital, which is accompanied by an electron pocket, an indicator of superconductivity. However, the EMott opens for the Se-rich samples between the lower Hubbard band and the upper Hubbard band, although the Se 4p band crosses EF and the p–d hybridization is enhanced. Such an opening also takes place in the CCDW Mott insulating phases for the S-rich samples (Supplementary Fig. 6a), indicating that the electron pocket in the NCCDW phase and the superconductivity could be destroyed by the Mott metal–insulator transition. The electron pocket is gapped in the Mott phase due to the enhanced electron correlation, indicating a competition between superconductivity and the Mott phase.

Since the superconductivity is only discovered in the x region where the Se/S ordering at the atomic scale takes place, the unique Se/S ordering within the star-of-David clusters may dominate the transport property, and is hence related to the presence of superconductivity, as well as the electron pocket (Supplementary Fig. 6b). In other words, the Se/S ordering and the electron pocket can be viewed as two critical factors for the superconductivity in the consideration of (i) the essential difference of the distribution of Se and S atoms with the star-of-David clusters between the SC and non-SC samples (Supplementary Fig. 6b), (ii) the dominant intensity contribution around the Γ point in whole momentum (k) space (Supplementary Fig. 6a) and (iii) the x dependence of the electron pocket in the density of states following the SC dome shape29. For these reasons, the superconductivity can therefore be characterized by the electron pocket, which is driven by the unexpected ordered superstructure.

Atomistic observation of a Se/S ordering in the x region, where the SC nature occurs, represents an important step forward in fully tailoring superconductivity in light of the fact that it is fragile against the Mott metal–insulator transition. Because the Ta 5d orbital materializes superconductivity, while the Se 4p orbital brings metallic phase, the unusual Se/S ordering surrounding Ta within the star-of-David clusters should be of paramount importance in creating SC states characterized by the electron pocket. Such a finding of atomic-scale anionic ordering in the SC-layered chalcogenides opens a novel research direction for manipulating SC states in low-dimensional electron systems via atomistic-ordering and -disordering engineering.

Methods

Sample fabrication

High-quality single crystals of 1T-TaS2−xSex (0≤x≤2) were grown by the chemical vapour transport method with iodine as a transport agent. The high-purity Ta, S and Se were mixed in chemical stoichiometry, and heated at 900 °C for 4 days in an evacuated quartz tube. The harvested TaS2−xSex powders and iodine (density: 5 mg cm−3) were then sealed in another quartz tube and heated for 10 days in a two-zone furnace, in which the source zone and growth zone were fixed at 950 and 850 °C, respectively. Analysis of crystal structures was performed by the X-ray diffraction using the Philips X’pert PRO diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation. The step size was 0.016°. The structural refinement based on the Rietveld analysis revealed that the Ta and S (Se) atoms occupied 1a (0, 0, 0) and 2d (1/3, 2/3, 1/4) sites, respectively. With the rise of x content, lattice parameters (a, c) and volume of unit cell (V) increased monotonously in that Se has a larger ionic radius than S (Supplementary Fig. 1c,d).

Transport property measurement

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) was measured in both the zero-field-cooled and field-cooled modes down to 2 K using the Quantum Design superconducting quantum interference device system. The applied magnetic field (H) is parallel to the c axis. The transport property was measured by a standard four-probe configuration in a physical property measurement system (Quantum Design). The temperature dependence of thermoelectric power S(T) were measured at temperatures down to 5 K.

TEM specimen preparation and imaging conditions

Thin-foil specimens for TEM and STEM imaging were prepared by cutting single crystals from [0001] (c axis) and [ ] directions (a axis). The slices were then mechanically ground till their thickness reached ~0.1 mm, followed by a dimpling down to ~20 μm. To make the electrons transparent, the dimpled slices were eventually thinned by a Ar-ion sputter beam using the PIPS 691 (Gatan Co. Ltd.). A gun voltage of 1–4 kV and an incident beam angle of 4–6° were adopted to avoid radiation damage. The selected-area diffraction pattern and TEM images were taken using the JEOL JEM-2010 F electron microscope operated at 200 kV. The HAADF and ABF images were taken with a 200-kV ARM-200FC STEM equipped with a probe corrector (CEOS Gmbh), offering an unprecedented opportunity to probe structures with sub-Ångström resolution. For the HAADF imaging, a probe convergence angle of ~22 mrad and a detector with an inner semi-angle of over 60 mrad were adopted. The ABF STEM images were taken with a detector of 6–25 mrad.

] directions (a axis). The slices were then mechanically ground till their thickness reached ~0.1 mm, followed by a dimpling down to ~20 μm. To make the electrons transparent, the dimpled slices were eventually thinned by a Ar-ion sputter beam using the PIPS 691 (Gatan Co. Ltd.). A gun voltage of 1–4 kV and an incident beam angle of 4–6° were adopted to avoid radiation damage. The selected-area diffraction pattern and TEM images were taken using the JEOL JEM-2010 F electron microscope operated at 200 kV. The HAADF and ABF images were taken with a 200-kV ARM-200FC STEM equipped with a probe corrector (CEOS Gmbh), offering an unprecedented opportunity to probe structures with sub-Ångström resolution. For the HAADF imaging, a probe convergence angle of ~22 mrad and a detector with an inner semi-angle of over 60 mrad were adopted. The ABF STEM images were taken with a detector of 6–25 mrad.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Ang, R. et al. Atomistic origin of an ordered superstructure induced superconductivity in layered chalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 6:6091 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7091 (2015).

References

Mathur, N. D. et al. Magnetically mediated superconductivity in heavy fermion compounds. Nature 394, 39–43 (1998).

Lefebvre, S. et al. Mott transition, antiferromagnetism, and unconventional superconductivity in layered organic superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 5420–5423 (2000).

Dagotto, E. Correlated electrons in high-temperature superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 763–840 (1994).

Damascelli, A., Hussain, Z. & Shen, Z. X. Angle-resolved photoemission studies of the cuprate supercondutors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 473–541 (2003).

Mattheiss, L. F. Band structures of transition-metal-dichalcogenide layer compounds. Phys. Rev. B 8, 3719–3740 (1973).

Gabovich, A. M., Voitenko, A. I. & Ausloos, M. Charge- and spin-density waves in existing superconductors: competition between Cooper paring and Peierls or excitonic instabilities. Phys. Rep. 367, 583–709 (2002).

Wilson, J. A., Di Salvo, F. J. & Mahajan, S. Charge-density waves and superlattices in the metallic layered transition metal dichalcogenides. Adv. Phys. 24, 117–201 (1975).

Fazekas, P. & Tosatti, E. Electrical, structural and magnetic properties of pure and doped 1T-TaS2 . Philos. Mag. B 39, 229–244 (1979).

Manzke, R., Buslaps, T., Pfalzgraf, B., Skibowski, M. & Anderson, O. On the phase transitions in 1T-TaS2 . Europhys. Lett. 8, 195–200 (1989).

Thomson, R. E., Burk, B., Zettl, A. & Clarke, J. Scanning tunneling microscopy of the charge-density-wave structure in 1T-TaS2 . Phys. Rev. B 49, 16899–16916 (1994).

Pillo, T. h. et al. Interplay between electron-electron interaction and electron-phonon coupling near the Fermi surface of 1T-TaS2 . Phys. Rev. B 62, 4277–4287 (2000).

Perfetti, L. et al. Time evolution of the electronic structure of 1T-TaS2 through the insulator-metal transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 067402 (2006).

Scruby, C. B., Williams, P. M. & Parry, G. S. The role of charge density waves in structural transformations of 1T-TaS2 . Philos. Mag. 31, 255–274 (1975).

Rossnagel, K. & Smith, N. V. Spin-orbit coupling in the band structure of reconstructed 1T-TaS2 . Phys. Rev. B 73, 073106 (2006).

Smith, N. V., Kevan, S. D. & Disalvo, F. J. Band structures of the layer compounds 1T-TaS2 and 2H-TaSe2 in the presence of commensurate charge-density waves. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 18, 3175–3189 (1985).

Zwick, F. et al. Spectral consequences of broken phase coherence in 1T-TaS2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 1058–1061 (1998).

Spijkerman, A., de Boer, J. L., Meetsma, A., Wiegers, G. A. & van Smaalen, S. X-ray crystal-structure refinement of the nearly commensurate phase of 1T-TaS2 in (3+2)-dimensional superspace. Phys. Rev. B 56, 13757–13767 (1997).

Hellmamn, S. et al. Ultrafast melting of a charge-density wave in the Mott insulator 1T-TaS2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 187401 (2010).

Eichberger, M. et al. Snapshots of cooperative atomic motion in the optical suppression of charge density waves. Nature 468, 799–802 (2010).

Ishizaka, K. et al. Femtosecond core-level photoemission spectroscopy on 1T-TaS2 using a 60-eV laser source. Phys. Rev. B 83, 081104 (R) (2011).

Peterson, J. C. et al. Clocking the melting transition of charge and lattice order in 1T-TaS2 with ultrafast extreme-ultraviolet angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 177402 (2011).

Hellmamn, S. et al. Time-domain classification of charge-density-wave insulators. Nat. Commun. 3, 1069 (2012).

Sipos, B. et al. From Mott state to superconductivity in 1T-TaS2 . Nat. Mater. 7, 960–965 (2008).

Xu, P. et al. Superconducting phase in the layered dichalcogenide 1T-TaS2 upon inhibition of the metal-insulator transition. Phys. Rev. B 81, 172503 (2010).

Li, L. J. et al. Fe-doping-induced superconductivity in the charge-density-wave system 1T-TaS2 . Europhys. Lett. 97, 67005 (2012).

Ang, R. et al. Real-space coexistence of the melted Mott state and superconductivity in Fe-substituted 1T-TaS2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 176403 (2012).

Liu, Y., Lu, W. J., Li, L. J., Ang, R. & Sun, Y. P. Coexistence of superconductivity and charge-density-wave domain in 1T-FexTa1-xSSe. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 252601 (2014).

Liu, Y. et al. Superconductivity induced by Se-doping in layered charge-density- wave system 1T-TaS2-xSex . Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 192602 (2013).

Ang, R. et al. Superconductivity and bandwidth-controlled Mott metal-insulator transition in 1T-TaS2-xSex . Phys. Rev. B 88, 115145 (2013).

Muller, D. A. Structure and bonding at the atomic scale by scanning transmission electron microscopy. Nat. Mater. 8, 263–270 (2009).

Findlay, S. et al. Robust atomic resolution imaging of light elements using scanning transmission electron microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 191913 (2009).

Pennycook, S. J. & Boatner, L. A. Chemically sensitive structure-imaging with a scanning transmission electron microscope. Nature 336, 565–567 (1988).

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Nakayama, T. Sato and T. Takahashi for useful discussions. This work was conducted in part in the Research Hub for Advanced Nano Characterization and the ‘Nanotechnology Platform’ at the University of Tokyo supported by the MEXT of Japan, and was supported in part by the Elements Strategy Initiative for Structural Materials via MEXT by Japan. Z.C.W. thanks financial supports from the Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (A) (grant no. 24686069), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (grant no. 11332013), JSPS and CAS under the Japan-China Scientific Cooperation Program, and Murata Science Foundation. R.A. and T.M. thank the financial supports from the NIMS Open Innovation Center of Japan. J.T. is grateful for the financial support from the NSFC under grant no. 11274234. Y.P.S. and W.J.L. thank the financial supports from National Key Basic Research and NSFC under grant nos 2011CBA00111 and U1232139.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A., C.L.C., Z.C.W. and T.M. conceived and designed the study. R.A., Y.L., W.J.L. and Y.P.S. fabricated the high-quality single crystals and carried out the transport property measurements. C.L.C., Z.C.W. and Y.I. prepared specimens, took images and conducted image processing. J.T., N.L. and Y.I. discussed the experimental results. All of the authors contributed to the interpretation of the data. R.A. and Z.C.W. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-6 (PDF 1171 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ang, R., Wang, Z., Chen, C. et al. Atomistic origin of an ordered superstructure induced superconductivity in layered chalcogenides. Nat Commun 6, 6091 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7091

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7091

This article is cited by

-

Thickness dependent charge density wave networks on thin 1T-TaS\(_2\)

Journal of the Korean Physical Society (2023)

-

Two-dimensional charge order stabilized in clean polytype heterostructures

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Understanding the Mott insulating state in 1T-TaS2 and 1T-TaSe2

AAPPS Bulletin (2022)

-

Multimorphism and gap opening of charge-density-wave phases in monolayer VTe2

Nano Research (2020)

-

Possible strain induced Mott gap collapse in 1T-TaS2

Communications Physics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.