Abstract

Cell fate specifications of multiciliate cells (MCCs) and ionocytes are commonly suppressed by the Notch pathway in developing epithelia, but are governed by different master regulators, suggesting the existence of a common regulator linking the Notch pathway to both MCC and ionocyte specifications. Here we show that a mab21 family gene, mab21-l3, represents the missing link. In Xenopus embryonic epidermis, mab21-l3 expression is specifically found in MCCs and ionocytes and is downregulated by the Notch pathway. Knockdown of mab21-l3 in Xenopus downregulates both MCC-specific and ionocyte-specific master genes, resulting in drastic loss of MCCs and ionocytes. In mouse tracheal epithelial cells, mab21-l3 expression is also downregulated by the Notch pathway and is required for MCC differentiation. Moreover, conditional gain of function of mab21-l3 rescues Notch-induced loss of MCCs and ionocytes in Xenopus. These results indicate that mab21-l3 acts downstream of the Notch pathway in cell fate specifications of MCCs and ionocytes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flow-generating multiciliate cells (MCCs) and ion-transporting ionocytes are found in epithelia of various organs in vertebrates. MCCs have hundreds of hair-like motile protrusions, multicilia, to generate extracellular fluid flow along epithelial surfaces1, while ionocytes (also known as ‘mitochondria-rich cells’, which include intercalated cells in mammalian kidney and clear cells in mammalian epididymis) selectively secrete or absorb ions and other small molecules to regulate body fluid homeostasis2,3,4. Both cells are essential for human physiological processes, and malformation of them is associated with human diseases, including bronchiectasis, hydrocephalus and distal tubule acidosis1,2. Cell fate specifications of MCCs and ionocytes are known to be suppressed by the Notch pathway in various developing epithelia5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. However, MCC-specific and ionocyte-specific transcriptional programmes are governed by different master regulators: a coiled-coil protein multicilin15 and a forkhead transcription factor foxj1 (refs 16, 17, 18) for MCCs and another forkhead transcription factor foxi1 (refs 7, 8, 9, 19, 20, 21) for ionocytes. This raises the possibility that an unidentified common regulator(s) links the Notch pathway to both MCC and ionocyte specifications.

In this study, we identify an evolutionarily conserved mab21 family gene, mab21-like 3 (mab21-l3), as a key common regulator representing the missing link. Our results suggest that mab21-l3 acts downstream of the Notch pathway in early phases of both MCC and ionocyte specifications, by regulating expression of master regulators for MCCs (multicilin and foxj1) and ionocytes (foxi1).

Results

Xenopus mab21-l3 is expressed in both MCCs and α-ionocytes

The Xenopus embryonic epithelium has been used as a model system to understand epithelial cell specification as it contains MCCs, ionocytes and mucus-secreting goblet cells7,21,22. During our screen identifying genes that show a characteristic expression pattern in the embryonic epithelium, we found that an evolutionarily conserved gene, mab21-l3, showed a salt-and-pepper pattern of expression (see below). Mab21 was first identified in Caenorhabditis elegans, and three orthologous genes, mab21-like 1 (mab21-l1), mab21-like 2 (mab21-l2) and mab21-l3, have been identified in vertebrates23,24. Among these three genes, mab21-l3 has been poorly studied. Xenopus mab21-l3 was recently shown to regulate dorsal development24, but its detailed expression pattern and role in epidermal development have not been examined. We first analysed the spatial expression pattern of Xenopus mab21-l3 by whole-mount in situ hybridization (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The expression was first detected in the presumptive ectoderm in the animal region at the early gastrula stage (stage 10.5), and became restricted to the ventral ectoderm with a spotted pattern at the late gastrula stage (stage 12/13). At neurula and tailbud stages (stage 14–30), mab21-l3 is expressed in the epidermis with a salt-and-pepper pattern.

In the Xenopus embryonic epidermis, two subtypes of ionocytes, α- and β-ionocytes, exist, both of which, like MCCs, are known to be distributed in a salt-and-pepper pattern7,21. We therefore examined whether mab21-l3 is expressed in MCCs and ionocytes. Embryos hybridized with a mab21-l3 antisense probe were subjected to double immunostaining with antibodies against acetylated α-tubulin (an MCC marker) and ae1 (an α-ionocyte marker; Fig. 1a). Cells with strong mab21-l3 expression (black arrowheads) were co-stained with the anti-ae1 antibody, while cells with weak mab21-l3 expression (yellow arrowheads) were co-stained with the anti-acetylated α-tubulin antibody. mab21-l3-expressing cells were positive for either ae1 or acetylated α-tubulin staining, suggesting that the mab21-l3 expression level in β-ionocytes is very low, if expressed. In situ hybridization combined with single immunostaining produced essentially the same results (Supplementary Fig. 1b,c). Thus, mab21-l3 is strongly expressed in α-ionocytes, weakly expressed in MCCs and little or very weakly expressed in β-ionocytes.

(a) Whole-mount in situ hybridization combined with double immunostaining indicates that mab21-l3 is strongly expressed in α-ionocytes and weakly expressed in MCCs at stage 31. Left panels are lateral views. Anterior is to the left and dorsal is upwards. Right panels are magnified images of the epidermis. mab21-l3 mRNA-expressing cells detected with in situ hybridization are dark blue. MCCs and α-ionocytes were identified by staining with anti-acetylated α-tubulin (red) and anti-ae1 (green) antibodies, respectively. Yellow arrowheads show MCCs weakly expressing mab21-l3. Black arrowheads show α-ionocytes strongly expressing mab21-l3. Essentially the same results were obtained in 19 embryos from five independent experiments. Scale bars, 500 μm (left panels) and 50 μm (right panels). (b) mab21-l3 is initially expressed in the inner cell layer, but later expressed in the outer cell layer, of Xenopus embryonic epidermis. The left panels show vertical sections of embryos processed for whole-mount in situ hybridization against mab21-l3. The right diagram shows the current model for MCC and ionocyte specification. In all panels, apical is at the top. Scale bars, 40 μm. Essentially the same results were obtained in two to five embryos of each stage from one to three independent experiments.

We then followed the behaviour of mab21-l3-expressing cells during early development, in which MCC progenitors (red) and ionocyte progenitors (yellow) commonly arise from uncommitted cells (green) in the inner cell layer of ventral ectoderm during gastrula stages (from stage 10 to 13) and then radially intercalate into the outer layer in a regular spacing pattern from mid to late neurula stages (from stage 17 to 21; see Fig. 1b, right). After intercalation is completed, these progenitors mature into MCCs and α/β-ionocytes, respectively, in the outer layer5,6,7,21 (see Fig. 1b, right). At stages 11–13, mab21-l3 is expressed in the inner cell layer of the epidermis (Fig. 1b, left). At stage 17, mab21-l3-expressing cells are located around the border between two layers. At stages 25–30, mab21-l3 expression is observed in the outer cell layer with a spotted pattern. These results demonstrate that the behaviour of mab21-l3-expressing cells closely resembles that of MCC and/or ionocyte progenitors, and thus raise the possibility that mab21-l3 is involved in MCC/ionocyte specification.

mab21-l3 is required for the formation of MCCs and ionocytes

We next performed knockdown of mab21-l3 with an antisense morpholino oligonucleotide (MO). Mab21-l3 MO, but not a five-base mismatch control (mab21-l3 5mis MO), markedly blocked translation from mab21-l3 mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 2). We co-injected control MO, mab21-l3 MO or mab21-l3 5mis MO with a lineage tracer fluorescein dextran into the left ventral blastomere of 4-cell-stage embryos. Injected embryos, in which uninjected right sides serve as an internal control, were analysed by whole-mount in situ hybridization for marker gene expression. Injection of mab21-l3 MO, but not that of control MO or mab21-l3 5mis MO, led to a drastic decrease in the number of cells expressing the α-ionocyte marker ae1 at stage 22 (Fig. 2a,b). Similarly, cells showing the normal expression level of pendrin, a β-ionocyte marker, were drastically reduced by mab21-l3 MO at stage 22 (Fig. 2c,d). Next we performed immunofluorescence staining of MO-injected embryos with an antibody against acetylated α-tubulin, an MCC marker. The number of MCCs was also drastically decreased in mab21-l3 morphants (Fig. 3a–c). These results indicate that mab21-l3 is required for the formation of both ionocytes and MCCs.

(a–d) Mab21-l3 MO leads to loss of ionocytes. Control MO, mab21-l3 MO or mab21-l3 5mis MO (30 ng each) was co-injected with the tracer fluorescein dextran (100 ng) into the animal region of the left ventral blastomere at the four-cell stage. Injected embryos at stage 22 were subjected for whole-mount in situ hybridization against ae1 or pendrin. (a,c) Lateral views of embryos are shown. A, anterior; P, posterior. Fluorescence views reveal distribution of injected materials. Scale bars, 500 μm. (b) The ratio of the number of ae1-expressing cells in the MO-injected side to that in the uninjected side. Shown is the average from embryos (control, n=23; mab21-l3 MO, n=22; mab21-l3 5mis MO, n=24) in three independent experiments. The error bar represents s.d. **P<0.01 by Tukey’s test. (d) The ratio of the number of cells showing normal strong pendrin expression in the MO-injected side to that in the uninjected side. Cells showing faint pendrin expression, which were frequently seen in the mab21-l3 MO-injected area, were omitted from quantification. Shown is the average from embryos (control, n=21; mab21-l3 MO, n=20; mab21-l3 5mis MO, n=20) in three independent experiments. The error bar represents s.d. **P<0.01 by Tukey’s test.

(a–c) Mab21-l3 MO leads to loss of MCCs. (a,b) Control MO, mab21-l3 MO or mab21-l3 5mis MO (30 ng each) was injected into the animal region of the left ventral blastomere at the four-cell stage. Injected embryos were fixed at stage 22–23, then stained with the acetylated α-tubulin antibody (green). (a) The lower panels show higher magnification of boxed areas in upper panels. The number of acetylated α-tubulin-positive MCCs was decreased in mab21-l3 MO-injected embryos (100%, n=14), but not affected in those injected with control MO (90%, n=21) or mab21-l3 5mis MO (79%, n=19). A, anterior; P, posterior. Scale bars, 500 μm (upper panels) and 50 μm (lower panels). (b) The ratio of the number of MCCs per field in the MO-injected side to that in the uninjected side. Shown is the average from embryos in two independent experiments. n, number of embryos scored. The error bar represents s.d. **P<0.01 by Tukey’s test. (c) Control MO, mab21-l3 MO or mab21-l3 5mis MO (60 ng each) was co-injected with the tracer mCherry-CAAX mRNA (200 pg) into the animal region of two ventral blastomeres at the four-cell stage. Injected embryos were fixed at stage 23 and then stained with the acetylated α-tubulin antibody (green). Images were acquired using the DeltaVision Optical Sectioning system. The right graph shows the average of the number of MCCs per field. The data were obtained from 12 embryos (four fields per embryo) in two independent experiments. Scale bars, 15 μm. The error bar represents s.d. **P<0.01 by Tukey’s test.

mab21-l3 regulates early specification of MCCs and ionocytes

Although mab21-l3 seems to be scarcely expressed in β-ionocytes, mab21-l3 MO markedly decreased the number of β-ionocytes at tailbud stages (Fig. 2c,d), leading to the hypothesis that mab21-l3 functions in ionocyte specification at earlier stages. It has been known that the master regulator for ionocyte specification, foxi1, starts to be expressed in progenitor cells at gastrula stages7. Whole-mount in situ hybridization showed that injection of mab21-l3 MO, but not that of control MO or mab21-l3 5mis MO, led to a dramatic decrease in foxi1 expression at the late gastrula stages (stages 12 and 13; Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. 3a). The results of real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) also indicated that mab21-l3 MO significantly reduces the expression level of foxi1 at stages 12 and 13 (Fig. 4d; Supplementary Fig. 3d). These results suggest that mab21-l3 functions in ionocyte specification at the upstream of foxi1. Next we examined the effect of mab21-l3 knockdown on the expression of the established master regulator for MCC specification, foxj1. Both whole-mount in situ hybridization and real-time qPCR analyses revealed that mab21-l3 MO led to a decrease in foxj1 expression at the late gastrula stage (Fig. 4b,d). Moreover, mab21-l3 MO reduced the expression level of a recently identified master regulator for MCC specification, multicilin (Fig. 4c,d; Supplementary Fig. 3b,d), which has been shown to act upstream of foxj1 (ref. 15). Because multicilin has been reported to promote cell cycle exit15, we examined cell proliferation in mab21-l3 knockdown embryos. Mab21-l3 MO significantly enhanced the accumulation of an M-phase marker, phospho-histone H3 (Fig. 4e), supporting the idea that mab21-l3 inhibits cell proliferation at least in part by inducing multicilin expression. These results show that mab21-l3 is required for MCC specification, acting upstream of the multicilin/foxj1 axis. The expression of the MCC progenitor marker α-tubulin was also suppressed by mab21-l3 MO at stages 12, 13 and 17 (Fig. 5a,b; Supplementary Fig. 3c,d). These results taken together indicate that mab21-l3 plays a crucial role in the formation of both MCC progenitors and ionocyte progenitors, functioning upstream of the established master regulators.

(a–d) mab21-l3 MO decreases foxi1, foxj1 and multicilin expressions. (a–c) Control MO, mab21-l3 MO or mab21-l3 5mis MO (a,c, 30 ng each; b, 40 ng each) was co-injected with fluorescein dextran (100 ng) into the left ventral blastomere at the four-cell stage, and embryos at stage 13 were subjected to whole-mount in situ hybridization. Ventral views of embryos are shown in left six panels, and fluorescence views reveal distribution of injected materials. foxi1 (a), foxj1 (b) and multicilin (c) expressions were decreased in mab21-l3 MO-injected embryos (foxi1, 100%, n=17; foxj1, 81%, n=32; multicilin, 95%, n=21), but not affected in those injected with control MO (foxi1, 100%, n=21; foxj1, 91%, n=35; multicilin, 94%, n=31) or mab21-l3 5mis MO (foxi1, 100%, n=14; foxj1, 100%, n=11; multicilin, 80%, n=30). The middle 12 panels show higher magnification of boxed areas in left 6 panels. The right graphs show the ratio of the foxi1-, foxj1- or multicilin-expressing cell number per field in the MO-injected side to that in the uninjected side. Shown is the average from embryos in two or three independent experiments. n, the number of embryos scored. (d) The indicated MO (60 ng each) was injected into two ventral blastomeres at the four-cell stage, and embryos at stage 13 were subjected to real-time qPCR analysis. Shown is the average of three or seven independent experiments. (e) Mab21-l3 MO enhances cell proliferation. Left panels, the indicated MO (80 ng each) was injected into two left blastomeres at the four-cell stage, and embryos were fixed at stage 13 for phospho-histone H3 staining. Dorsal is upwards. A, anterior; P, posterior. The right graph shows the ratio of the number of phospho-histone H3-positive cells in the injected side to that in the uninjected side. Shown is the average from embryos (control MO, n=15; mab21-l3 MO, n=19) in two independent experiments. (a–e) Error bars represent s.d. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by Tukey’s test (a–d) or unpaired Welch’s t-test (e). Scale bars, 500 μm (a–c, left 6 panels; e) and 50 μm (a–c, middle 12 panels).

(a,b) Mab21-l3 MO decreases α-tubulin expression. The indicated MO (30 ng each) was co-injected with fluorescein dextran (100 ng) into the left ventral blastomere at the four-cell stage, and embryos at stage 13 (a) or 17 (b) were subjected to whole-mount in situ hybridization against α-tubulin. Ventral (a) or lateral (b) views of embryos are shown in left 6 (a) or upper 12 (b) panels. A, anterior; P, posterior in b. α-tubulin expression was decreased in mab21-l3 MO-injected embryos (stage 13, 100%, n=15; stage 17, 100%, n=15), but not affected in those injected with control MO (stage 13, 100%, n=14; stage 17, 100%, n=14) or mab21-l3 5mis MO (stage 13, 100%, n=6; stage 17, 88%, n=8). The middle (a) or lower (b) 12 panels show higher magnification of boxed areas in left 6 (a) or upper 12 (b) panels. Scale bars, 500 μm (a, left panels; b, upper panels) and 50 μm (a, middle panels; b, lower panels). The right graphs show the ratio of the α-tubulin-expressing cell number per field in the MO-injected side to that in the uninjected side. Shown is the average from embryos in one (mab21-l3 5mis MO) or two (control MO and mab21-l3 MO) independent experiments. n, the number of embryos scored. The error bar represents s.d. **P<0.01 by Tukey’s test.

A previous study reported that depletion of the ionocyte master regulator foxi1 leads to the loss of MCCs at later stages (apparent stages 26–27, although the authors did not mention the stage number)25, raising the possibility that the loss of MCCs observed in mab21-l3 knockdown embryos is secondarily caused by the loss of ionocytes. To address this issue, we examined whether foxi1 knockdown leads to the loss of MCCs at earlier stages. At stage 22, ae1 or pendrin expression was drastically decreased, but α-tubulin expression was not or only slightly affected, by the translation-blocking foxi1 MOs (MO1 plus MO2)26 or the splice-blocking foxi1 MO (SBMO)25 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Also, another group reported that α-tubulin expression (at apparent stage 25, although the authors did not mention the stage number) is not affected by foxi1 knockdown in the related species X. tropicalis21. Taken together, the loss of ionocytes does not largely affect early specification of MCCs before stage 25, but it affects maturation of MCCs at later stages. Our results also demonstrate that mab21-l3 knockdown decreases expression of MCC markers at earlier stages such as stages 12, 13 and 17 (Figs 4b–d and 5; Supplementary Fig. 3b–d). Thus, the loss of MCCs in mab21-l3 knockdown embryos occurs at very early stages and is not secondarily caused by the loss of ionocytes. Also, we examined whether co-expression of foxi1 rescues the loss of ionocytes and MCCs in mab21-l3 knockdown embryos. Injection of mab21-l3 MO alone resulted in the loss of ae1, pendrin and α-tubulin expressions (Supplementary Fig. 5). Co-injection of mab21-l3 MO with foxi1 mRNA was able to induce weak ae1 expression as well as strong pendrin expression, but was unable to restore α-tubulin expression (Supplementary Fig. 5), indicating that the loss of MCCs in mab21-l3 knockdown embryos can be observed even in the condition activating the ionocyte differentiation programme. Taken together, requirement of mab21-l3 in MCC specification seems to be independent of the presence or absence of ionocytes, thus decreasing the possibility that the loss of MCCs observed in mab21-l3 knockdown embryos is secondarily caused by the loss of ionocytes.

Next we addressed whether mab21-l3 is sufficient for MCC/ionocyte specification. Mab21 family proteins have been suggested to function as a transcriptional regulator27,28, and exogenously expressed mab21-l3 protein was localized to the nucleus in Xenopus ectoderm (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Because injection of synthesized mRNA encoding myc-tagged wild-type mab21-l3 induced cell death at blastula stages in a preliminary experiment (18/18 (100%) death, 1 ng mab21-l3-myc mRNA per embryo; 12/20 (60%) death, 400 pg mab21-l3-myc mRNA per embryo), we used a glucocorticoid-inducible form of mab21-l3 (mab21-l3-hGR), whose nuclear translocation can be conditionally induced by dexamethasone (DEX). Embryos unilaterally injected with mab21-l3-hGR mRNA were treated with DEX at gastrula stages, and then cultured until tailbud stages, at which the number of MCCs, α-ionocytes or β-ionocytes in the injected side was compared with that in the uninjected side. DEX treatment weakly but significantly increased the number of MCCs, but not that of α-ionocytes or β-ionocytes (Fig. 6a; Supplementary Fig. 6). Moreover, overexpression of mab21-l3-hGR increased the expression level of multicilin in both ectodermal explants and whole embryos at stage 12 (Fig. 6b), although DEX dependency was low possibly because of a short treatment period (from stage 10 to 12). These results taken together suggest that mab21-l3 is sufficient to promote specification of MCCs, but not ionocyte specification, which may require an additional factor(s).

(a) Forced nuclear translocation of mab21-l3 slightly increases the number of MCCs. mab21-l3-hGR mRNA (100 pg) was injected into the left ventral blastomere at the four-cell stage, and injected embryos were cultured with or without DEX (10 μM) from stage 10.25/10.5. At stage 33/34, embryos were harvested for whole-mount in situ hybridization against α-tubulin (no DEX treatment, n=107; DEX treatment, n=108, from five independent experiments), and the number of α-tubulin-positive cells was counted. In left four panels, dorsal is upwards and anterior is to the right (uninjected side) or left (injected side). The middle four panels show higher magnification. Scale bars, 500 μm (left panels) and 50 μm (middle panels). Right graphs show the distribution (histogram) and the average (upper right inset) of the ratio of the number of α-tubulin-positive cells in the injected side to that in the uninjected side. The error bar represents s.d. *P<0.05 by t-test. (b) Mab21-l3 upregulates multicilin expression. The tracer fluorescein dextran (200 ng) was co-injected with or without mab21-l3-hGR mRNA (400 pg) into the animal region of two blastomeres at the two-cell stage. Animal caps isolated at stage 10 (left) or whole embryos (right) were cultured with or without DEX (10 μM) and harvested at stage 12 for real-time qPCR analysis of multicilin expression. Shown is the average of five or three independent experiments. The error bar represents s.d.

In the Xenopus embryonic epidermis, MCCs and ionocytes arise from the inner cell layer where mab21-l3 is expressed (see Fig. 1b), whereas mucus-secreting goblet cells arise from the outer cell layer. We investigated whether mab21-l3 affects differentiation of goblet cells. The expression of Xeel, the goblet cell marker22, was reduced by mab21-l3 knockdown at stages 17 and 22 (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b). However, at stage 11, expression of outer-layer-specific markers, WRPW-bHLH protein enhancer of split-6e (esr6e) and grainyhead-like 3 (grhl3)29,30, was not significantly affected by mab21-l3 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 7c). This result suggests that at stage 11 mab21-l3 is dispensable for specification of outer-layer cells including goblet cell progenitors. At stage 12, expression of grhl3 was unaffected, but expression of esr6e or epidermal keratin (xk81a1, another outer-layer marker) was downregulated by mab21-l3 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 3e). Thus, outer layer-specific gene expression was initially unaffected, but partly affected later in mab21-l3 knockdown embryos. We also found that the Notch pathway, the established negative regulator for MCC and ionocyte specification, was able to inhibit differentiation of goblet cells at later stages (Supplementary Fig. 8a). We therefore speculate that differentiation of outer-layer progenitors into goblet cells is disturbed at later stages in mab21-l3 MO-injected embryos, possibly due to secondary effects caused by the loss of MCCs and ionocytes at early stages.

Because both ionocytes and MCCs arise from the inner layer of early ectoderm (see Fig. 1b, right), it is possible that the loss of ionocytes and MCCs in mab21-l3 knockdown embryos is secondarily caused by global defects of inner-layer patterning at early stages. To address this point, we examined expression of inner-layer markers, p63, vestigial-like 4 (vgll4) and hyaluronan synthase 1 (has1)30,31. At stage 12, mab21-l3 knockdown significantly decreased expression of p63, but not that of vgll4 or has1 (Supplementary Fig. 3e), suggesting that inner-layer-specific gene expression is at least partly normal in the absence of mab21-l3. Thus, mab21-l3 does not play a crucial role in controlling all aspects of inner-layer patterning.

mab21-l3 acts downstream of the Notch pathway

Next we investigated the relationship between mab21-l3 and Notch signalling. The intracellular domain of Notch (NICD) has been widely used to induce Notch pathway activation. Overexpression of Xenopus NICD (xNICD) led to marked reduction in mab21–13 expression at stages 13 and 31/32 (Fig. 7a,b; Supplementary Fig. 8a). We also co-injected xNICD mRNA with fluorescein dextran into one ventral blastomere at the 32-cell stage, and the injected embryos, which were cultured until stage 27, were hybridized with a mab21-l3 antisense probe, followed by immunostaining with an antibody against E-cadherin to visualize the plasma membrane (Fig. 7c). mab21-l3 expression could be seen in xNICD-negative epithelial cells, but not in xNICD-positive epithelial cells (Fig. 7c), suggesting that the inhibitory action of Notch on mab21-l3 expression may be cell autonomous. We then searched for a mediator that acts downstream of Notch to repress mab21-l3 transcription. Certain members of the transcriptional repressor Hes family, including hes1 and hes5, are known as major targets of the Notch pathway32. Thus, a Xenopus close homologue of mammalian hes5, esr6e, could be a candidate, because esr6e is known to be induced by the Notch pathway to repress MCC specification5. Injection of esr6e mRNA decreased mab21-l3 expression at stages 13 and 31/32 (Fig. 7a,b). Moreover, expression of the α-ionocyte marker ae1 and the β-ionocyte marker pendrin was downregulated by injection of esr6e mRNA, but was upregulated by that of esr6e Δb (a dominant negative form of esr6e)5 mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 8b). These results indicate that esr6e mediates the action of Notch signalling to repress mab21-l3 transcription and MCC/ionocyte specification.

(a,b) Notch and esr6e suppress mab21-l3 expression. xNICD mRNA (400 pg) or esr6e mRNA (400 pg) was co-injected with fluorescein dextran (100 ng) into the left ventral blastomere at the four-cell stage, and embryos at stage 13 (a) or 27 (b) were subjected to whole-mount in situ hybridization against mab21-l3. Ventral (a) or lateral (b) views of embryos are shown. Fluorescence views reveal distribution of injected materials. Boxed areas in left 6 (a) or upper 4 (b) panels are shown at higher magnification in right (a) or lower (b) panels. Scale bars, 500 μm (a, left panels; b, upper panels) and 50 μm (a, right panels; b, lower panels). mab21-l3 expression was markedly decreased in embryos injected with xNICD mRNA (stage 13, 83%, n=12, from two independent experiments; stage 27, 91%, n=11, from one experiment) or esr6e mRNA (stage 13, 74%, n=34, from three independent experiments; stage 27, 73%, n=51, from four independent experiments), but not affected in those injected with the tracer alone (stage 13, 100%, n=16, from three independent experiments). (c) Notch activation cell autonomously suppresses mab21-l3 expression. xNICD mRNA (400 pg) was co-injected with fluorescein dextran (100 ng, green) into one ventral blastomere at the 32-cell stage, and embryos at stage 27 were subjected to whole-mount in situ hybridization against mab21-l3 (dark blue) followed by staining with the anti-E-cadherin antibody (red) and Hoechst (blue). The confocal image of the epidermis is shown. The schematic illustration of the merged image is shown in lower left. Scale bars, 10 μm. Essentially the same results were obtained by confocal microscopic observation of three embryos at stage 27 in one experiment and stereomicroscopic observation of four embryos at stage 16 in another experiment.

We reasoned that ectopic expression of mab21-l3 should rescue Notch-dependent inhibition of MCC/ionocyte specification, if the inhibition is mediated through Notch-dependent downregulation of mab21-l3. We first confirmed Notch inhibition of MCC/ionocyte specification. Injection of xNICD mRNA alone led to the decrease in foxi1 and multicilin expressions at stage 13 (Fig. 8a,b, second left). At later stages, xNICD suppressed ae1 expression, pendrin expression and acetylated α-tubulin abundance (Fig. 9a,b, second top panels), as also indicated by the bar graph (Fig. 9c, white and light grey bars), which represents the ratio of the number of ae1-, pendrin- or acetylated α-tubulin-positive cells in the injected side to that in the uninjected side. These results are consistent with the previous finding that the Notch pathway suppresses both MCC and ionocyte specification. For rescue experiments, we used mab21-l3-hGR. When embryos co-injected with xNICD and mab21-l3-hGR mRNA were cultured with DEX from the late blastula stage (stage 9), the xNICD-induced decrease in foxi1 or multicilin expression was cancelled by mab21-l3-hGR in a DEX-dependent manner (Fig. 8a,b, rightmost and second right). Moreover, mab21-l3-hGR with DEX restored ae1 expression, pendrin expression and acetylated α-tubulin abundance at later stages (Fig. 9a,b, first and second bottom panels), as indicated also by the bar graph (Fig. 9c, dark grey and black bars). Thus, exogenous expression of mab21-l3 is sufficient to overcome Notch-dependent inhibition of MCC/ionocyte specification. It should be noted that DEX treatment from the late gastrula stage (stage 13) could not restore α-tubulin expression (Supplementary Fig. 9), suggesting that mab21-l3 begins to function at late blastula or early gastrula stages, the timing before MCC/ionocyte progenitors are formed. These results taken together demonstrate that mab21-l3 regulates early phases of MCC/ionocyte specification by acting downstream of the Notch pathway and upstream of master regulators (Fig. 9d).

(a,b) The Notch-induced decrease in foxi1 and multicilin expression is rescued by forced nuclear translocation of mab21-l3. Indicated combinations of xNICD (200 pg) and mab21-l3-hGR (100 pg) mRNAs were co-injected with the tracer fluorescein dextran (100 ng) into the left ventral blastomere at the four-cell stage, and injected embryos were cultured with or without DEX (10 μM) from stage 9. At stage 13, embryos were harvested for whole-mount in situ hybridization against foxi1 (a) or multicilin (b). Ventral views of embryos are shown. Fluorescence views reveal distribution of injected materials. Boxed areas in left eight panels are shown at higher magnification in right panels. Scale bars, 500 μm (left panels) and 50 μm (right panels). foxi1 and multicilin expressions were markedly decreased in xNICD mRNA-injected embryos (foxi1, 92%, n=12; multicilin, 86%, n=28) or DEX-untreated embryos injected with xNICD and mab21-l3-hGR mRNAs (foxi1, 90%, n=20; multicilin, 80%, n=30), but not largely affected in tracer-injected embryos (foxi1, 100%, n=16; multicilin, 94%, n=17) or DEX-treated embryos injected with xNICD and mab21-l3-hGR mRNAs (foxi1, 58%, n=19; multicilin, 66%, n=29), in two independent experiments.

(a–c) The Notch-induced decrease in the number of MCCs and ionocytes is rescued by forced nuclear translocation of mab21-l3. Indicated combinations of xNICD (200 pg) and mab21-l3-hGR (100 pg) mRNAs were co-injected with fluorescein dextran (100 ng) into the left ventral blastomere at the four-cell stage, and injected embryos were cultured with or without DEX (10 μM) from stage 9. At stage 32, embryos with fluorescence were harvested for whole-mount in situ hybridization against pendrin or ae1. Embryos hybridized with pendrin probe were further subjected to immunostaining with the anti-acetylated α-tubulin antibody. Lateral views of embryos are shown. Dorsal is upwards and anterior is to the right (uninjected side) or left (injected side). In a, magnified images of the epidermis were also shown (right). Scale bars, 500 μm (a,b, whole images) and 50 μm (a, magnified images). The bar graph (c) shows the ratio of the number of pendrin-, acetylated α-tubulin- or ae1-positive cells in the injected side to that in the uninjected side. Shown is the average from embryos in four independent experiments (tracer-injected embryos, n=73 (pendrin), n=66 (acetylated α-tubulin), n=76 (ae1); xNICD mRNA-injected embryos, n=53 (pendrin), n=53 (acetylated α-tubulin), n=52 (ae1); DEX-untreated embryos injected with xNICD and mab21-l3-hGR mRNAs, n=72 (pendrin), n=70 (acetylated α-tubulin), n=62 (ae1); DEX-treated embryos injected with xNICD and mab21-l3-hGR mRNAs, n=79 (pendrin), n=75 (acetylated α-tubulin), n=71 (ae1)). The error bar represents s.d. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by Tukey’s test. (d) Mab21-l3 acts downstream of Notch and upstream of multicilin, foxj1 and foxi1 to control both MCC and ionocyte specification.

In response to overexpression of xNICD, the numbers of β-ionocytes, MCCs and α-ionocytes showed a 36, 26 and 19% decrease, respectively (Fig. 9c), suggesting that the sensitivity to Notch activation of β-ionocyte, MCC and α-ionocyte specification is high, medium and low, respectively. Interestingly, expression of mab21-l3 was almost undetectable, weak and strong in β-ionocytes, MCCs and α-ionocytes, respectively (Fig. 1a). Thus, the responsiveness to Notch activation was inversely correlated with the expression level of mab21-l3. These results suggest that the expression level of mab21-l3 is one of the factors influencing Notch responsiveness and cell fate decision in MCC/ionocyte development.

Mouse Mab21-l3 is required for MCC differentiation

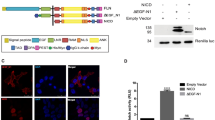

We finally examined whether the role of mab21-l3 is conserved in mammals. Overexpression of mouse Notch intracellular domain (mNICD) in mouse tracheal epithelial cells (mTECs) markedly upregulated mouse Hes5, an established Notch-inducible gene that shows close homology to Xenopus esr6e, and significantly downregulated mouse Mab21-l3 (Fig. 10a). These results indicate that the Notch pathway is able to inhibit mab21-l3 expression in mice as well as in Xenopus. Next we assessed a role of mouse Mab21-l3 in MCC differentiation. It has been previously established that MCCs start to be induced at about 3–4 days after exposure of confluent mTECs to an air–liquid interface (ALI)33. First we examined changes in gene expression before and after ALI exposure. Multicilin exhibited peak expression around 2 days after ALI exposure (ALI+2), while Mab21-l3 exhibited peak expression around the starting time of ALI exposure (ALI+0) (Fig. 10b), consistent with our hypothesis that mab21-l3 acts upstream of multicilin to regulate early phases of MCC specification. In agreement with this result, the BioGPS database ( http://biogps.org/#goto=genereport&id=126868) indicates that human MAB21-L3 gene exhibits peak expression at ALI+0 in the previous microarray data of ALI-treated bronchial epithelial cells (the GEO accession number GSE5264)34.

(a) Mab21-l3 expression is repressed by Notch activation in mTECs. mTECs were infected with lentivirus expressing GFP alone (Mock) or co-expressing mouse Notch intracellular domain (mNICD) and GFP, and then subjected to real-time qPCR analysis of Mab21-l3 and Hes5 expression. Shown is the average of four independent experiments. The error bar represents s.d. **P<0.01 by unpaired t-test. (b) Mab21-l3 expression precedes Multicilin expression during MCC differentiation of mTECs. The expression levels of Multicilin and Mab21-l3 in mTECs (from 2 days before ALI exposure to 15 days after ALI exposure) were analysed by real-time qPCR. Shown is the average of three (ALI+1) or four (ALI−2, 0, +2, +5, +7, +10 and +15) independent experiments. The error bar represents s.d. (c) The efficacy of lentivirus expressing shRNAs against mouse Mab21-l3 in NIH3T3 cells. Cells were infected with lentivirus expressing control LacZ shRNA, mMab21-l3 shRNA #1 or mMab21-l3 shRNA #2, and then subjected for real-time qPCR analysis of Mab21-l3 expression. Shown is the average of three independent experiments. The error bar represents s.d. **P<0.01 by Dunnett’s test. (d) mMab21-l3 shRNAs inhibit MCC differentiation in mTECs. mTECs were infected with lentivirus co-expressing EGFP (green) with control LacZ shRNA, mMab21-l3 shRNA #1 or mMab21-l3 shRNA #2. At ALI+6, cells were fixed and stained with the anti-acetylated α-tubulin antibody (red). Multicilia formed in infected cells are yellow in merged images. Scale bars, 50 μm. (e) Quantification of the result in d. The percentage of infected cells with multicilia among all infected cells was calculated by counting the cell number in 6–42 (control shRNA), 9–47 (mMab21-l3 shRNA #1) or 9–49 (mMab21-l3 shRNA #2) different fields per experiment. The left graph shows results of four independent experiments (n, the total number of infected cells). The middle graph shows the average of the percentage. The right graph shows the ratio of the percentage in mMab21-l3 shRNA-infected cells to that in control shRNA-infected cells. The error bar represents s.d. **P<0.01 by Dunnett’s test.

We next designed two short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) targeting mouse Mab21-l3, mMab21-l3 shRNA #1 and mMab21-l3 shRNA #2, both of which inhibited Mab21-l3 expression in NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 10c). Each shRNA and GFP was co-expressed in mTECs by lentiviral delivery, and at 6 days after ALI exposure (ALI+6), the multicilia were visualized by immunostaining with the anti-acetylated α-tubulin antibody. While multicilia were formed in 17% of GFP-positive cells expressing control shRNA, they were formed in only 8 and 7% of GFP-positive cells expressing mMab21-l3 shRNA #1 and #2, respectively (Fig. 10d,e). We also examined tracheal progenitor cells called basal cells, which are known to be abundantly present in the mTEC culture33. The percentage of cells positive for the basal cell marker p63 was not significantly changed by mMab21-l3 shRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 10), ruling out the possibility that Mab21-l3 knockdown has nonspecific toxic effects on mTECs. These results indicate that Mab21-l3 is required for MCC differentiation in mouse.

Discussion

In this study, we uncover a missing molecular link between the Notch pathway and MCC/ionocyte specification. We have identified an evolutionarily conserved gene mab21-l3 as a bifunctional regulator of both MCC and ionocyte specification. Moreover, our rescue experiments suggest that Notch/esr6e-driven repression of mab21-l3 is a key step to restrict the number of MCCs and ionocytes to an appropriate level. We have also shown that mab21-l3 functions upstream of the established master regulators for MCCs (multicilin and foxj1) and ionocytes (foxi1). As mab21-l3 expression is positively regulated by foxi1 (ref. 24), there is a feedback relationship between foxi1 and mab21-l3 (see Fig. 9d). This positive feedback may ensure robust progression of ionocyte differentiation. Also, miR-449 microRNAs, whose genomic locus is close to the multicilin gene15, could be functionally linked with mab21-l3, because they have been shown to regulate MCC differentiation through inhibition of the Notch signalling pathway in both Xenopus embryonic epidermis and mammalian airway epithelial cells35.

Although our results were mainly obtained in the Xenopus embryonic epidermis, two main points were also shown to be conserved in mammals; that is, the Notch pathway-dependent repression of mab21-l3 expression and the essential role of mab21-l3 in MCC specification. Because the Notch pathway is known to restrict MCC and ionocyte specification in various organs, including mouse lung12,13, mouse kidney14, zebrafish pronephros10,11 and zebrafish skin8,9, the Notch/mab21-l3 signalling axis could have a conserved role in MCC/ionocyte specification in vertebrates.

In our rescue experiment in Xenopus, the sensitivity to Notch activation was low in α-ionocytes (which strongly express mab21-l3), medium in MCCs (which weakly express mab21-l3) and high in β-ionocytes (which show no or little mab21-l3 expression). This implies that the expression level of mab21-l3 is one of the factors that influence the responsiveness to Notch. Because a search of NCBI GEO and BioGPS databases reveals that mammalian mab21-l3 is expressed in various tissues including oesophagus, rectum and skin, mab21-l3 may fine-tune the responsiveness to Notch in many other biological contexts.

Previous studies have suggested that the mab21 family member could act as a transcriptional regulator27,28. Our results with mab21-l3-hGR also suggest that mab21-l3 primarily functions in the nucleus. We thus speculate that mab21-l3 protein may interact with additional nuclear proteins such as transcription factors, coactivators, corepressors or chromatin-remodelling factors to activate transcription of genes required for cell fate specification. Because mab21-l3 plays a dual role in MCC and ionocyte specification, the constituents of the mab21-l3 complex may vary in a cell-type or context-dependent manner. Detailed molecular mechanisms of the action of mab21-l3 should be elucidated in future studies.

Methods

Molecular cloning and plasmid construction

The entire coding regions of Xenopus laevis mab21-l3, α-tubulin, foxj1, foxi1, ae1, pendrin, Xeel, multicilin and esr6e were amplified by PCR from late gastrula or neurula complementary DNAs (cDNAs) using primers designed based on deposited sequences (the GenBank/EMBL accession numbers are as follows: mab21-l3, BC073481; α-tubulin, BC077769; foxj1, AJ609390; foxi1, BC042303; ae1, BC072920; pendrin, AY174063; Xeel, AB105372; multicilin, BC124892; esr6e, AF146087). These amplified sequences were cloned into the pBluescript vector (for RNA probe synthesis) or the pCS2+ vector (for RNA probe synthesis or mRNA synthesis). A cDNA fragment (5,251–7,575 bp (base pair) of the coding sequence with accession number M33874), which encodes the intracellular domain of Xenopus Notch (xNICD), was obtained by PCR and cloned into the HA-pCS2+ vector. A cDNA fragment (5,230–7,596 bp of the coding sequence with accession number AB100603), which encodes the intracellular domain of mouse Notch (mNICD), was obtained by PCR and cloned into the lentiviral vector. The sequences of primer pairs used were as follows: Xenopus mab21-l3 (forward 5′- GGTAGATCTATGAAGGGAGTGAAGGCTGAGGATG -3′; reverse 5′- GGTAGATCTTCAGCACACGGAGGAGGCACCTTG -3′); Xenopus α-tubulin (forward 5′- GCCAGATCTATGAGGGAATGCATCTCAGTTC -3′; reverse 5′- GGCAGATCTTTACTCCTCTCCTTCATCTTCATC -3′); Xenopus foxj1 (forward 5′- CCATCGATGGATGTTTGACCTGCCCAGGGCGGCC -3′; reverse 5′- CCGCTCGAGTTATATATAGGAACCCAAGGACGA -3′); Xenopus foxi1 (forward 5′- CCATCGATGGATGAGTGCATTTGATCCACAAGCA -3′; reverse 5′- CCGCTCGAGTTATACTTCTGTACCTTCTCTGTT -3′); Xenopus ae1 (forward 5′- CCATCGATGGATGGCATCTAAAGATCAATCCGAC -3′; reverse 5′- CCGCTCGAGTTAAAAAGGAAAATATTTCCTGCG -3′); Xenopus pendrin (forward 5′- CCGGAATTCATGGCAACAGCAAGAATGGATATC -3′; reverse 5′- CCGCTCGAGTCAGTGTGCCAGTGATCGGAGAGC -3′); Xenopus Xeel (forward 5′- CCGCTCGAGCGGATGGGCAAGATGTTGTCATATAGCCTGTTG -3′; reverse 5′- GGAAGATCTTCCTTAACGGTAGAAGAGCATCACAGCTGCCTC -3′); Xenopus multicilin (forward 5′- CGCGGATCCATGCCGGATTTGTCCAACCGGTTGAG -3′; reverse 5′- CCGCTCGAGTTAATTGGGAACCCATCTAAATTTGTAGCC -3′); Xenopus esr6e (forward 5′- GGAAGATCTTCCATGGAGAGAAAGCCAGTGATTGAG -3′; reverse 5′- CCGGAATTCCGGTTAAGGAGGTGAAAGAACCTGCCAAG -3′); xNICD (forward 5′- ATTAGATCTAATAAGAAGCGTCGCCGTGAACACGG -3′; reverse 5′- CGGAGATCTTTACTTGAAAGCTTCAGGTATGTGGG -3′); and mNICD (forward 5′- TCCGGAATTCGCCACCATGGTGCTGCTGTCCCGCAAGCG -3′; reverse 5′- GCGCGGATCCTTATTTAAATGCCTCTGGAATG -3′).

Embryo manipulation

X. laevis embryos were obtained by in vitro fertilization and cultured in 0.1 × MBS (1.0 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 8.8 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM KCl, 0.24 mM NaHCO3, 0.082 mM MgSO4, 0.03 mM Ca(NO3)2 and 0.041 mM CaCl2). For animal cap assay, ectodermal explants were dissected at stage 10 and harvested at indicated stages for real-time qPCR. mRNAs or antisense MOs were injected into the animal region of indicated blastomeres at the indicated stage (5–400 pg of each mRNA, 2–40 ng of each MO, per blastomere). Frogs were bred and handled with care, according to the established manual36.

Real-time qPCR

Total RNA from Xenopus embryos was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and cDNA was synthesized using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Total RNA extraction from mammalian cells was performed with Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized by QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). For real-time qPCR analysis, we used 7300 real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen). Duplicate PCR reactions were performed for each sample in each experiment. The gene expression levels were normalized to those of ornithine decarboxylase (odc) in Xenopus embryos or Gapdh in mouse cells. ‘Relative expression’ in bar graphs indicates the ratio of the normalized expression level in each sample to that in one sample used as a control. Thus, relative expression in one sample used as a control is always defined as 1.0 in each experiment. The sequences of primer pairs used were as follows: Xenopus odc (forward 5′- TGCAAGTTGGAGACTGGATG -3′; reverse 5′- CATCAGTTGCCAGTGTGGTC -3′); Xenopus multicilin (forward 5′- TTCCCTCCACGGAGCAATAC -3′; reverse 5′- CAGTCAGACTCACCTGGAGC -3′); Xenopus α-tubulin (forward 5′- ACGTCTCTCTGTTGACTATGGC -3′; reverse 5′- GTCTGAGTGCTCAAGTGTTGTG -3′); Xenopus foxj1 (forward 5′- GGGACTCCCATGGTTACAGG -3′; reverse 5′- GAGGTGGACGAGGAAATGGG -3′); Xenopus foxi1 (forward 5′- CAAGCACATTCTCCACCACG -3′; reverse 5′- TCGCTGAGGACTAGGCATTG -3′); Xenopus esr6e (forward 5′- GCATACCCAGGAGCACGGACAC -3′; reverse 5′- GAGAGGGTGCAGGGAGGCAAG -3′); Xenopus vestigial-like 4 (vgll4) (forward 5′- CGCTCTGACCATGGACCTG -3′; reverse 5′- GGGTCACTCCGTAATGCTGC -3′); Xenopus hyaluronan synthase 1 (has1) (forward 5′- GCCCAGTGGTGGCACAAGCATC -3′; reverse 5′- ATGGTGCCGGCATAGATGAGGCG -3′); Xenopus p63 (forward 5′- GCCAAGCTCTACCTTTGATGC -3′; reverse 5′- AGGTGGCTGACTTTGCTGTG -3′); Xenopus grhl3 (forward 5′- GAAGGGCGTTAAAGGTGTCC -3′; reverse 5′- CAGACTGCACGATGAATGAGC -3′); Xenopus epidermal keratin (xk81a) (forward 5′- CACCAGAACACAGAGTAC -3′; reverse 5′- CAACCTTCCCATCAACCA -3′); mouse Gapdh (forward 5′- AACATCAAATGGGGTGAGGCC -3′; reverse 5′- GTTGTCATGGATGACCTTGGC -3′); mouse Mab21-l3 (forward 5′- CAAAGTCCTGCAGTTGTTCCG -3′; reverse 5′- GCAACCCAAACCGTAGTGC -3′); mouse Multicilin (forward 5′- GCCAGCTCGGTGAATCTGAG -3′; reverse 5′- GTAACCACCGGTGACTGTCC -3′); and mouse Hes5 (forward 5′- TACCTGAAACACAGCAAAGCCTTC -3′; reverse 5′- TAAAGCAGCTTCATCTGCGTGTCG -3′).

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Whole-mount in situ hybridization36 on albino or wild-type Xenopus embryos was performed using a robot (InsituPro, Intavis). Embryos were fixed in MEMFA (100 mM MOPS, pH 7.4, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgSO4 and 3.7% formaldehyde) for 2 h, dehydrated and stored in methanol. After rehydration, embryos were treated with 5 μg ml−1 proteinase K in PBS containing 0.1% Tween20, incubated in 100 mM triethanolamine (pH 8) for 12 min, incubated in 100 mM triethanolamine (pH 8) containing 0.25% acetic anhydride for 12 min and then refixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min. After washing, embryos were hybridized with digoxigenin-labelled probes for 18 h at 58 °C, and then subjected to anti-digoxigenin antibody staining. The colour reaction was performed using BM purple. The digoxigenin-labelled antisense and sense probes were synthesized from full-length cDNA sequences of mab21-l3, α-tubulin, foxj1, foxi1, ae1, pendrin and Xeel. For whole-mount in situ hybridization combined with immunostaining, we omitted the proteinase K step.

Morpholino oligonucleotides

Antisense MOs were obtained from Gene Tools. The MO sequences were as follows: mab21-l3 MO, 5′- ATCCTCAGCCTTCACTCCCTTCATC -3′ (the sequence complementary to the predicted start codon is underlined); mab21-l3 5mis MO, 5′- ATCCTgAcCgTTCAgTCgCTTCATC -3′ (lower case letters indicate mismatched bases); a standard control oligo (control MO), 5′- CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA -3′; foxi1 MO1 (ref. 26), 5′- GTGCTTGTGGATCAAATGCACTCAT -3′ (the sequence complementary to the predicted start codon is underlined); foxi1 MO2 (ref. 26), 5′- AGGTCACAAATACACCTGTACTAGC -3′; and foxi1 SBMO25, 5′- ATAATTGCCCTTGCCTGTAAAGAAAA -3′. These MOs were resuspended in sterile water.

Immunoblotting

Embryos were lysed in a buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1% NP-40, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM vanadate, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 1% Protease Inhibitor cocktail (Sigma #8340). The lysate was centrifuged and the supernatant was used for immunoblotting with antibodies against Myc (9E10, Santa Cruz #sc-40) or GFP (JL-8, Clontech #632381).

Immunofluorescence staining

For whole-mount immunofluorescence staining, embryos injected with indicated mRNA or MOs were fixed in MEMFA (100 mM MOPS, pH 7.4, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgSO4 and 3.7% formaldehyde) for 2 h, dehydrated and stored in methanol. After rehydration, embryos were bleached, and then incubated in either of three blocking solutions: 2% skim milk in PBS (for V5 staining), 10% fetal bovine serum in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5% dimethylsulphoxide (for acetylated α-tubulin staining), and 2% BSA in PBS with 0.1% Tween20 (for ae1 staining and E-cadherin staining). The primary antibodies used were: anti-V5 antibody (Invitrogen #R960-25, 1:1,000), anti-acetylated α-tubulin antibody (Sigma #T7451, 1:1,000), anti-E-cadherin antibody (BD Bioscience #610182, 1:300) and monoclonal anti-ae1 antibody (IDSHB clone IVF-12, 1:300). Bound primary antibodies were detected with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen #A-11029, 1:1,000) or Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen #A-11031, 1:1,000). Images of the embryos were acquired using stereomicroscope SZX12 (Olympus), SZX16 (Olympus) or the DeltaVision Optical Sectioning system (Applied Precision). The confocal image was obtained by using a confocal laser scanning microscope, A1 (Nikon). For immunofluorescence staining of mTECs, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min, and then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS at room temperature for 10 min. After blocking with 3% BSA in PBS at room temperature for 1 h, cells were incubated with 3% BSA in PBS containing the anti-acetylated tubulin antibody or the anti-p63 antibody (Santa Cruz #sc-8343, 1:100) at 4 °C overnight, washed with PBS and then incubated with 3% BSA in PBS containing Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse IgG (1:400) or Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen #A11036, 1:400) for 30 min at room temperature. Nuclei were simultaneously stained with Hoechst. Cells were finally mounted in Mowiol. Images were acquired by using an Axioplan2 microscope (Zeiss).

Preparation of lentiviral vectors

Constructs expressing shRNAs against mouse Mab21-l3 (mMab21-l3 shRNAs) were generated by subcloning the silencing oligonucleotides into the ApaI/EcoRI site of the CSII-U6-MCS-EGFP vector, which was designed to co-express shRNA and the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) reporter37. The sequences of silencing oligonucleotides are as follows: mMab21-l3 shRNA #1-sense, 5′- AAAGCTACCCACCAGATTTCTCAAGAGAAAATCTGGTGGGTAGCTTTCCTTTTTT -3′; mMab21-l3 shRNA #1-antisense, 5′- AATTAAAAAAGGAAAGCTACCCACCAGATTTTCTCTTGAGAAATCTGGTGGGTAGCTTTGGCC -3′; mMab21-l3 shRNA #2-sense, 5′- GCAGAAGGTTGCTGCTATACTCTCAAGAGAAGTATAGCAGCAACCTTCTGCTTTTTTTT -3′; and mMab21-l3 shRNA #2-antisense, 5′- AATTAAAAAAAAGCAGAAGGTTGCTGCTATACTTCTCTTGAGAGTATAGCAGCAACCTTCTGCGGCC -3′. To generate constructs expressing mNICD, the mNICD cDNA was cloned into the CSII-EF-MCS-CMV-EGFP vector, which was generated by replacing the IRES sequence of the CSII-EF-MCS-IRES-EGFP vector37 with the CMV promoter. To produce the recombinant lentivirus, the shRNA-expressing CSII-U6-MCS-EGFP vector or the mNICD-expressing CSII-EF-MCS-CMV-EGFP vector was co-transfected with pCAG-HIVgp and pCMV-VSV-G-RSV-Rev into HEK293T cells using FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent (Promega). Culture supernatants containing the virus were collected 48 h after transfection. For testing the shRNA efficiency, NIH3T3 cells were cultured with the unconcentrated supernatants for 24 h. For infection of mTECs, the lentiviral supernatants were concentrated to achieve 107–108 infectious units per millilitre.

Culture of mTECs

Primary mTEC culture was performed according to the published protocol33. mTECs were isolated from tracheas of 7 weeks old, wild-type C57BL/6 J male mice, seeded onto Transwell Clear permeable membranes (Corning, #3460) coated with rat-tail collagen, and then cultured with mTEC plus medium33. For mNICD overexpression experiments, cells were spin infected with the lentivirus in the presence of 5 μg ml−1 polybrene (Sigma) at 2 days after seeding38, and then harvested at confluency for real-time qPCR analysis. For MCC differentiation experiments, cells reaching confluency were exposed to an ALI and cultured with mTEC basic medium33 containing 2% Nu-Serum (Becton-Dickinson). For shRNA experiments, cells were spin infected with the shRNA-expressing lentivirus in the presence of 5 μg ml−1 polybrene at 2 days after seeding38, and then exposed to ALI after reaching confluency. All mouse experiments were conducted in accordance with the Regulation on Animal Experimentation at Kyoto University and approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Kyoto University.

Statistics

Cell counting was done using Image J Software. The t-test was performed using the EXCEL Software (Microsoft). The Tukey’s test and the Dunnett’s test were performed using the SPSS Software (IBM). Results are considered significant when P<0.05.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Takahashi, C. et al. mab21-l3 regulates cell fate specification of multiciliate cells and ionocytes. Nat. Commun. 6:6017 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7017 (2015).

References

Fliegauf, M., Benzing, T. & Omran, H. When cilia go bad: cilia defects and ciliopathies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 880–893 (2007).

Forgac, M. Vacuolar ATPases: rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 917–929 (2007).

Brown, D. & Breton, S. Mitochondria-rich, proton-secreting epithelial cells. J. Exp. Biol. 199, 2345–2358 (1996).

Hwang, P. P. & Chou, M. Y. Zebrafish as an animal model to study ion homeostasis. Pflugers Arch. 465, 1233–1247 (2013).

Deblandre, G. A., Wettstein, D. A., Koyano-Nakagawa, N. & Kintner, C. A two-step mechanism generates the spacing pattern of the ciliated cells in the skin of Xenopus embryos. Development 126, 4715–4728 (1999).

Stubbs, J. L., Davidson, L., Keller, R. & Kintner, C. Radial intercalation of ciliated cells during Xenopus skin development. Development 133, 2507–2515 (2006).

Quigley, I. K., Stubbs, J. L. & Kintner, C. Specification of ion transport cells in the Xenopus larval skin. Development 138, 705–714 (2011).

Hsiao, C. D. et al. A positive regulatory loop between foxi3a and foxi3b is essential for specification and differentiation of zebrafish epidermal ionocytes. PLoS ONE 2, e302 (2007).

Janicke, M., Carney, T. J. & Hammerschmidt, M. Foxi3 transcription factors and Notch signaling control the formation of skin ionocytes from epidermal precursors of the zebrafish embryo. Dev. Biol. 307, 258–271 (2007).

Ma, M. & Jiang, Y. J. Jagged2a-notch signaling mediates cell fate choice in the zebrafish pronephric duct. PLoS Genet. 3, e18 (2007).

Liu, Y., Pathak, N., Kramer-Zucker, A. & Drummond, I. A. Notch signaling controls the differentiation of transporting epithelia and multiciliated cells in the zebrafish pronephros. Development 134, 1111–1122 (2007).

Guseh, J. S. et al. Notch signaling promotes airway mucous metaplasia and inhibits alveolar development. Development 136, 1751–1759 (2009).

Tsao, P. N. et al. Notch signaling controls the balance of ciliated and secretory cell fates in developing airways. Development 136, 2297–2307 (2009).

Jeong, H. W. et al. Inactivation of Notch signaling in the renal collecting duct causes nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 3290–3300 (2009).

Stubbs, J. L., Vladar, E. K., Axelrod, J. D. & Kintner, C. Multicilin promotes centriole assembly and ciliogenesis during multiciliate cell differentiation. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 140–147 (2012).

Chen, J., Knowles, H. J., Hebert, J. L. & Hackett, B. P. Mutation of the mouse hepatocyte nuclear factor/forkhead homologue 4 gene results in an absence of cilia and random left-right asymmetry. J. Clin. Invest. 102, 1077–1082 (1998).

Stubbs, J. L., Oishi, I., Izpisua Belmonte, J. C. & Kintner, C. The forkhead protein Foxj1 specifies node-like cilia in Xenopus and zebrafish embryos. Nat. Genet. 40, 1454–1460 (2008).

Yu, X., Ng, C. P., Habacher, H. & Roy, S. Foxj1 transcription factors are master regulators of the motile ciliogenic program. Nat. Genet. 40, 1445–1453 (2008).

Blomqvist, S. R. et al. Distal renal tubular acidosis in mice that lack the forkhead transcription factor Foxi1. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1560–1570 (2004).

Blomqvist, S. R., Vidarsson, H., Soder, O. & Enerback, S. Epididymal expression of the forkhead transcription factor Foxi1 is required for male fertility. EMBO J. 25, 4131–4141 (2006).

Dubaissi, E. & Papalopulu, N. Embryonic frog epidermis: a model for the study of cell-cell interactions in the development of mucociliary disease. Dis. Model. Mech. 4, 179–192 (2011).

Hayes, J. M. et al. Identification of novel ciliogenesis factors using a new in vivo model for mucociliary epithelial development. Dev. Biol. 312, 115–130 (2007).

Mariani, M. et al. Two murine and human homologs of mab-21, a cell fate determination gene involved in Caenorhabditis elegans neural development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 2397–2406 (1999).

Sridharan, J., Haremaki, T., Jin, Y., Teegala, S. & Weinstein, D. C. Xmab21l3 mediates dorsoventral patterning in Xenopus laevis. Mech. Dev. 129, 136–146 (2012).

Mir, A. et al. FoxI1e activates ectoderm formation and controls cell position in the Xenopus blastula. Development 134, 779–788 (2007).

Suri, C., Haremaki, T. & Weinstein, D. C. Xema, a foxi-class gene expressed in the gastrula stage Xenopus ectoderm, is required for the suppression of mesendoderm. Development 132, 2733–2742 (2005).

Baldessari, D., Badaloni, A., Longhi, R., Zappavigna, V. & Consalez, G. G. MAB21L2, a vertebrate member of the Male-abnormal 21 family, modulates BMP signaling and interacts with SMAD1. BMC Cell Biol. 5, 48 (2004).

Choy, S. W., Wong, Y. M., Ho, S. H. & Chow, K. L. C. elegans SIN-3 and its associated HDAC corepressor complex act as mediators of male sensory ray development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 358, 802–807 (2007).

Chalmers, A. D., Welchman, D. & Papalopulu, N. Intrinsic differences between the superficial and deep layers of the Xenopus ectoderm control primary neuronal differentiation. Dev. Cell 2, 171–182 (2002).

Chalmers, A. D. et al. Grainyhead-like 3, a transcription factor identified in a microarray screen, promotes the specification of the superficial layer of the embryonic epidermis. Mech. Dev. 123, 702–718 (2006).

Tríbulo, C. et al. ΔNp63 is regulated by BMP4 signaling and is required for early epidermal development in Xenopus. Dev. Dyn. 241, 257–269 (2012).

Kageyama, R., Ohtsuka, T. & Kobayashi, T. The Hes gene family: repressors and oscillators that orchestrate embryogenesis. Development 134, 1243–1251 (2007).

You, Y. & Brody, S. L. Culture and differentiation of mouse tracheal epithelial cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 945, 123–143 (2013).

Ross, A. J., Dailey, L. A., Brighton, L. E. & Devlin, R. B. Transcriptional profiling of mucociliary differentiation in human airway epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 37, 169–185 (2007).

Marcet, B. et al. Control of vertebrate multiciliogenesis by miR-449 through direct repression of the Delta/Notch pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 693–699 (2011).

Sive, H. L., Grainger, R. M. & Harland, R. M. The Early Development of Xenopus laevis: A Laboratory Manual Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press (2000).

Okamoto, K., Fujisawa, J., Reth, M. & Yonehara, S. Human T-cell leukemia virus type-I oncoprotein Tax inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis by inducing cellular FLIP through activation of NF-kappaB. Genes Cells 11, 177–191 (2006).

Vladar, E. K. & Brody, S. L. Analysis of ciliogenesis in primary culture mouse tracheal epithelial cells. Methods Enzymol. 525, 285–309 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Y. Takahashi and R. Tadokoro (Kyoto University) for help with confocal fluorescence microscopy and H. Miyoshi (Riken Tsukuba Institute) for lentivirus vectors. We also thank M. Matsuda, T. Araki and members of the Nishida laboratory for technical advice and helpful discussion. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (to E.N. and M.K.) and Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST), Japan Science and Technology (to E.N.). C.T. is a Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The ae1 monoclonal antibody developed by M. Jennings was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by the University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.T. and M.K. conceived the study. C.T. designed and performed the experiments with the help of M.K., T.S. and K.M. C.T., M.K., T.S. and E.N. wrote the manuscript. M.K. and E.N. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-10 (PDF 6727 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Takahashi, C., Kusakabe, M., Suzuki, T. et al. mab21-l3 regulates cell fate specification of multiciliate cells and ionocytes. Nat Commun 6, 6017 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7017

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7017

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.