Abstract

Strong exciton–photon coupling is the result of a reversible exchange of energy between an excited state and a confined optical field. This results in the formation of polariton states that have energies different from the exciton and photon. We demonstrate strong exciton–photon coupling between light-harvesting complexes and a confined optical mode within a metallic optical microcavity. The energetic anti-crossing between the exciton and photon dispersions characteristic of strong coupling is observed in reflectivity and transmission with a Rabi splitting energy on the order of 150 meV, which corresponds to about 1,000 chlorosomes coherently coupled to the cavity mode. We believe that the strong coupling regime presents an opportunity to modify the energy transfer pathways within photosynthetic organisms without modification of the molecular structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Green sulfur bacteria grow anaerobically in sulfur-rich environments and are often found at the very lowest levels of the photic zone, such as in the bottom of stratified lakes, deep in the sea and near geothermal vents1. In such ecological niches, each bacterium may receive only a few hundred photons per second2,3,4. Thus, it is generally assumed that the light-harvesting complex (LHC) of these bacteria has evolved to efficiently collect and use the small amount of light available.

The main optical antenna structures in green sulfur bacteria are chlorosomes. These are generally oblate spheroid organelles ~100–200 nm in length, 30–70 nm in width and 30–40 nm thick5. A single chlorosome may contain up to 250,000 bacteriochlorophyll c/d/e (BChl c/d/e) molecules4,6,7 that are self-assembled into tube-like or lamellae aggregates8,9,10,11,12,13,14 and are enclosed within in a protein–lipid monolayer15. Absorption of a photon results in the creation of a molecular exciton, which is transported to the next subunit of the LHC—a baseplate, which is located on one side of the chlorosome surface. The energy then sinks through an intermediate Fenna–Matthews–Olson (FMO) complex to a reaction centre where it is used in the production of chemical compounds.

Efficient light harvesting requires strong light absorption combined with the fast energy relaxation that drives the exciton towards the reaction centre, protecting it from reemission and non-radiative recombination. Strong and coherent interaction between the pigment molecules in LHCs results in the formation of delocalized exciton states with the energies sufficiently different from non-interacting pigments16,17. Such excitons are then transferred across these collective as well as single-pigment states. Ultrafast energy transfer in the chlorosomes has been reported previously18,19,20. While these studies did not observe coherent exciton dynamics, such a process cannot be excluded.

Strong exciton–photon coupling is the result of a coherent exchange of energy between an exciton and a resonant photonic mode. The coupling manifests as a mixing in the energetic dispersions of the cavity and exciton modes and the formation of the cavity–polariton quasiparticle, which can be described as a linear mixture of the photon and exciton. The polariton energy dispersion takes the form of two ‘branches’ that anti-cross when the cavity-mode energy is tuned through the exciton energy. These are the polariton branches and are termed the upper polariton branch (UPB) and lower polariton branch (LPB) for the branches that exist above and below the exciton energy, respectively. The magnitude of the energetic splitting of the branches at exciton–photon resonance is the Rabi splitting energy ħΩ. Optical microcavities provide a convenient system in which to explore the strong coupling regime due to their relatively straightforward fabrication and simple tuning of the cavity-mode energy through angular-dependent measurements. Typical cavity structures consist of two mirrors separated on the order of hundreds of nanometres with the excitonic material located within the cavity. The requirements of strong coupling include a large absorption oscillator strength and narrow absorption line width for the exciton, and small cavity losses into leaky modes.

Strong coupling in microcavities has been demonstrated with a wide range of excitonic systems including semiconductor quantum wells21,22,23, quantum dots24,25, bulk semiconductors26,27, nanowires28, small organic molecules29,30,31, J-aggregates32,33,34, polymers35,36 and molecular crystals37,38,39. Organic materials have also been shown to strongly couple to the surface plasmons of metallic films40,41 and nanoparticles42,43. Recently, strong coupling between the surface plasmons of a metallic film and β-carotene molecules was demonstrated44. Several studies have discussed modified absorption, emission and energy transfer in natural LHCs weakly coupled with quantum dots45, plasmonic particles46 and optical cavities47,48.

In this paper we demonstrate that the exciton states in the chlorosome can be coherently coupled to the vacuum electromagnetic field confined in an optical microcavity, thereby creating polariton modes. In addition to the demonstration of chlorosome–cavity coupling, our work opens a new avenue to modify the energy landscape in the LHCs. We show that the energy of polariton modes can be detuned from the bare exciton states on the order of 100 meV, which is comparable to the energy difference between the chlorosome and the baseplate. We suggest that such structures could be used for the strong coupling of living photosynthetic bacteria with light to create ‘living polaritons’.

Results

Chlorosome film topology and cavity structure

Figure 1a,b shows atomic force microscope (AFM) topology maps of a poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) film containing chlorosomes (4:1 weight ratio) on length scales of 10 × 10 μm and 1 × 1 μm, respectively. The film surface displays features of sizes 50–250 nm, similar to the size of chlorosomes, and has a large root mean square surface roughness of ~10 nm with surface protrusions reaching a maximum of 100 nm. For comparison, AFM topology images of a PVA film without chlorosomes is shown in Fig. 1c,d on length scales of 10 × 10 μm and 1 × 1 μm, respectively. The root mean square surface roughness of this film is on the order of 1 nm with no large features visible.

The microcavity structure used in the experiment is shown in Fig. 2a. It consists of a 205-nm-thick film of PVA with suspended chlorosomes between two 40-nm-thick semitransparent mirrors. The chlorosome, BChl c aggregate and BChl c molecule are depicted in Fig. 2b–d, respectively. A transmission electron microscope image of the chlorosomes is shown in Fig. 2e. Figure 2f shows the optical extinction (sum of absorbance and scattering) of a control film of chlorosomes in PVA. The absorption band of the chlorosome is visible as a peak at 750 nm on top of a wavelength-independent scattering component of ~0.06. An ‘empty’ cavity was also fabricated that contained a 205-nm-thick film of PVA with no chlorosomes.

(a) A microcavity was fabricated which consisted of a 205-nm-thick PVA film containing chlorosomes between two 40-nm-thick semi-transparent silver mirrors. (b) The chlorosomes contain large aggregates of BChl c molecules within a protein–lipid monolayer. (c) The BChl c molecules (shown in d) self-assemble into tube-like structures. (e) Transmission electron microscope image of chlorosomes obtained using a negative scanning technique by dissolving the chlorosome in 2% uranyl acetate69. Scale bar is 100 nm. (f) Extinction of a 205-nm-thick film of chlorosomes in a PVA matrix.

Transmission and reflectivity measurements

Figure 3a(i) and (ii) shows the measured angular-dependent transmission and reflectivity measurements recorded from the empty microcavity. In both cases a single peak/dip is seen in the spectrum of each angle corresponding to the cavity mode. The line width of the cavity mode at 16° is ~20 nm, corresponding to a cavity Q-factor of 40 and a photon confinement time of 15 fs. We have modelled the empty cavity transmission and reflectivity spectra with the transfer matrix method (TMM), whose output is presented in Fig. 3a(iii) and (iv), respectively (in transverse electric polarized light). The model uses a constant refractive index of 1.53 for the PVA and no absorption or scattering is included in the PVA layer. There is excellent agreement between the observed cavity dispersion and the TMM modelling. In particular, the observed mode visibility and line width are well reproduced by the TMM indicating that the absorption and scattering in the PVA layer are negligible, as would be expected from the high surface quality of the film revealed by AFM. The cavity-mode energy (Eγ), is given by  where θ is the observation angle, neff is the effective intracavity refractive index and Eγ(0) is the cavity cut-off energy that for a λ/2 cavity of length L is given by

where θ is the observation angle, neff is the effective intracavity refractive index and Eγ(0) is the cavity cut-off energy that for a λ/2 cavity of length L is given by  . The fit to the cavity-mode energy is shown as a red dashed line in Fig. 3a.

. The fit to the cavity-mode energy is shown as a red dashed line in Fig. 3a.

(a) Experimental angular-dependent (i) transmission and (ii) reflectivity of an ‘empty’ PVA cavity and TMM-modelled spectra of the same cavity in (iii) transmission and (iv) reflectivity. Fitted cavity dispersion is shown as a gray dashed line. (b) Experimental angular-dependent (i) transmission and (ii) reflectivity of a chlorosome-containing PVA cavity and TMM-modelled spectra of the same cavity in (iii) transmission and (iv) reflectivity. Fitted cavity-mode and exciton energies are shown as dashed gray and black lines, respectively, and polariton branch dispersions are shown as white dashed lines. (c) Strongly coupled transmission spectrum at resonance (54°). The chlorosome film absorbance (scattering subtracted from Fig. 2f) is also shown in green. (d) Mixing coefficients of the polariton branches.

The angular-dependent transmission and reflectivity spectra of the microcavity containing chlorosomes are shown in Fig. 3b(i) and b(ii), respectively. Two peaks/dips can be seen clearly in the data that undergo an anti-crossing about the chlorosome exciton energy, indicating that the system is operating in the strong coupling regime. The energy of the polariton branches can be described by the coupled oscillator model49.

where Ex is the exciton energy, ħΩ is the Rabi splitting energy, Ep is the polariton energy and  and

and  are the mixing coefficients that describe the fraction of exciton and photon in the polariton state and can be shown to be given by

are the mixing coefficients that describe the fraction of exciton and photon in the polariton state and can be shown to be given by  . The observed transmission peak positions are fitted with equation (1), with Eγ(0), neff, Ex and ħΩ as fitting parameters. We find that the coupled system displays a Rabi splitting energy of ħΩ=156 meV and detuning of Δ=Eγ(0)−Ex=−164 meV. The fitted polariton branch positions are shown as white dashed lines in Fig. 3b, with the photon mode and exciton wavelengths shown with gray and black dashed lines, respectively. The chlorosome exciton energy Ex found from the fit is redshifted by ~12 nm with respect to absorption peak. It has previously been observed that in strongly coupled microcavities containing J-aggregates the exciton resonance appears blueshifted with respect to the absorption peak50,51. This was ascribed to the asymmetric shape of the absorption band and residual oscillator strength lying in higher energy states. A similar effect may be responsible for the redshift observed here, with some oscillator strength being at lower energy than the absorption peak. The cavity transmission spectrum at the resonance angle (54°) is shown in Fig. 3c. We note that the effective refractive index of the chlorosome-containing film is found through fitting to the two-level model to be ~1.7, which leads to an extended optical path length in the cavity in comparison to the PVA-only cavity, resulting in the cavity-mode energy being redshifted. The excitonic and photonic mixing coefficients of the polariton branches are shown in Fig. 3d.

. The observed transmission peak positions are fitted with equation (1), with Eγ(0), neff, Ex and ħΩ as fitting parameters. We find that the coupled system displays a Rabi splitting energy of ħΩ=156 meV and detuning of Δ=Eγ(0)−Ex=−164 meV. The fitted polariton branch positions are shown as white dashed lines in Fig. 3b, with the photon mode and exciton wavelengths shown with gray and black dashed lines, respectively. The chlorosome exciton energy Ex found from the fit is redshifted by ~12 nm with respect to absorption peak. It has previously been observed that in strongly coupled microcavities containing J-aggregates the exciton resonance appears blueshifted with respect to the absorption peak50,51. This was ascribed to the asymmetric shape of the absorption band and residual oscillator strength lying in higher energy states. A similar effect may be responsible for the redshift observed here, with some oscillator strength being at lower energy than the absorption peak. The cavity transmission spectrum at the resonance angle (54°) is shown in Fig. 3c. We note that the effective refractive index of the chlorosome-containing film is found through fitting to the two-level model to be ~1.7, which leads to an extended optical path length in the cavity in comparison to the PVA-only cavity, resulting in the cavity-mode energy being redshifted. The excitonic and photonic mixing coefficients of the polariton branches are shown in Fig. 3d.

TMM was again used to model the chlorosome cavity system. The film absorption was fitted to a Lorentzian oscillator model that allows the real (n) and imaginary (k) parts of the refractive index to the calculated. The scattering is included in the TMM model by incorporating the observed offset in the extinction spectrum into the imaginary part of the film refractive index. The refractive index dispersion of the chlorosome film used in modelling the cavity is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The modelled transmission and reflectivity spectra are shown in Fig. 3b(iii) and (iv), respectively. The dispersions of the polariton branches show good agreement with the experimentally observed spectra. Importantly, the Rabi splitting (75 nm) remains larger than the broadened cavity-mode line width despite the additional scattering52. From TMM we find that the scattering reduces the cavity Q-factor to 12 (photon confinement time of 5 fs). Strong coupling has previously been observed in metallic cavities with a similar Q-factor using J-aggregates as the coupling medium53. It should be noted that the coupling strength is in fact maximized when the line widths of the photon and exciton are well matched52,54, hence the broadened cavity-mode line width is not too detrimental to the strong coupling.

Discussion

The magnitude of the Rabi splitting energy may be used to gain an order-of-magnitude estimate of the number of chlorosomes involved in the formation of the polariton mode. The Rabi splitting energy is given by equation (2)55, where N is the number of coupled oscillators, μ is the dipole moment of the coupled oscillators, V is the mode volume of the cavity mode and  is a unit vector parallel to the polarization of the electric field in the cavity.

is a unit vector parallel to the polarization of the electric field in the cavity.

We estimate the λ/2 mode volume56 to be 15.7 (λ/neff)3 (assuming mirror reflectivities of 95% as found through TMM) where neff=1.8. This is an upper limit as it does not take into account in-plane scattering that will reduce the mode volume. We assume that each chlorosome contains an average of 200,000 BChl c monomers, the square of the monomer transition dipole |μ|2=30 D2 (ref. 57), and the average angle between the transition dipoles and the chlorosome’s main axis is about 28° (ref. 58). It is likely that the spin-coating process does result in some preferential orientation of chlorosomes in the plane of the film. Then, the number of coherently coupled chlorosomes estimated with equation (2) and assuming that the chlorosomes are aligned parallel to the confined E-field is ~1,000. It should be noted that the intermolecular coupling in the aggregate of BChls only redistributes the oscillator strength between the electronic transitions keeping the product |μ|2N the same. Thus, the transition dipoles μ and the number of states N in equation (2) can be taken to be those of the BChl monomers, provided that the cavity frequency is shifted from the monomer transition to the absorption spectrum of the aggregate, and the cavity line is broad enough such that the optical mode interacts resonantly with all optically allowed electronic transitions.

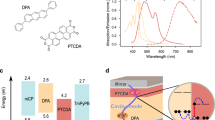

Subsequently, we discuss the possibility to modify the energy transfer pathways in LHCs of green sulfur bacteria using optical microcavities. The structure of the complete LHC is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. A schematic of the energy levels within the light-harvesting system is shown in Fig. 4 (green box). Following absorption of a photon by the chlorosome, the resulting exciton is transferred to the baseplate in <12 ps (ref. 59), followed by a transfer to the FMO complex that is suggested to occur in <200 ps (ref. 60). Finally, a very fast exciton transfer from the FMO complex to the reaction centre occurs on the timescale of ~1 ps (ref. 61). In order for efficient energy harvesting to occur, these transfer rates should be significantly faster than the excited state lifetimes of isolated components.

Energy level diagram of a green sulfur bacteria LHC coupled to an optical cavity. The red arrows show the energy transport pathway in an unperturbed LHC. Strong interaction of the cavity photons with the chlorosome exciton states result in formation of polariton branches with the Rabi splitting about 150 meV. The green arrows show possible energy pathways in the coupled system.

When the chlorosome strongly couples to the cavity mode, two new energy levels are created about the chlorosome energy. While it may be possible for other isolated components, especially the FMO complex, to strongly couple to a cavity mode, the vast majority of the absorption cross-section within the complete light-harvesting system is contributed from the chlorosome, hence we discuss the case where only the chlorosome has sufficient oscillator strength to strongly couple. Polariton states on the lower branch are shifted to lower energy than the uncoupled exciton and hence can overlap with the absorption band of the chlorosome baseplate at ~790 nm and the FMO complex at ~810 nm. The chlorosome absorption band is now ‘hidden’ behind the cavity mirrors and hence can no longer be resonantly excited by a photon of 750-nm wavelength. Instead, three different excitation mechanisms are possible depending on the photon energy. (i) A high-energy photon well above the 750-nm chlorosome absorption band can non-resonantly excite the chlorosome. The created ‘hot’ exciton will rapidly relax through thermal interactions into the exciton band of the chlorosome. From here the chlorosome exciton can either proceed to the baseplate as in the case of the uncoupled system or transfer to a polariton state on the LPB. From time-resolved measurements on strongly coupled J-aggregate systems (the closest studied analogue to the present system), the exciton relaxes to the LPB polariton on a timescale of ~5 ps (ref. 62). This is similar to or slightly faster than the chlorosome exciton to baseplate transfer rate, hence this may be viewed as a competitive pathway. From the LPB the exciton may be transferred either to the baseplate or to the FMO complex depending on the cavity Rabi splitting and detuning. (ii) A photon of energy resonant with the UPB may be absorbed directly by a polariton state on the UPB. UPB polariton states can relax to the exciton band on the timescale of tens of femtoseconds62, from where it can relax to the baseplate or LPB as before. Owing to the extremely fast UPB to exciton relaxation, we believe it is unlikely to scatter from the UPB polariton state directly to the baseplate—however, we do not rule this out. (iii) A photon of appropriate energy may be absorbed directly into a LPB state followed by one of the relaxation pathways described above. We note that the lifetime of the LPB polariton states is dependent on the photon and exciton mixing components in the state. This parameter, along with the polariton branch energy, can be easily tuned through angle in a microcavity structure, potentially allowing the efficiency of energy transfer to be tuned in the same structure and without modification of the molecular structure of the LHC components. One of the possible energy transfer paths is shown in Fig. 4 (green arrows). Here, due to the energy level alignment the photon energy can bypass the baseplate states via the LPB.

Relatively little is known about the energy transfer efficiency of excitons throughout the entire LHC, and it will be interesting to see if bypassing certain exciton states in the LHC will increase the efficiency of the antenna. This may in turn have implications for the rate of bacterial growth.

Since there are ~200–250 chlorosomes in each Chlorobaculum tepidum bacteria63, it is expected that if ~4 bacteria could occupy the cavity-mode volume, they could strongly couple to the cavity. The bacterial cell is 0.6–0.8 μm long64, hence it may indeed be possible to reach this limit to create ‘living polaritons’ and therefore directly investigate the effect of tuning the LHC energy levels on bacterial growth.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated strong coupling between a low-Q optical cavity and the chlorosome of green sulfur bacteria with a Rabi splitting of ~150 meV. The chlorosomes introduce large amounts of scattering into the microcavity system; however, this damping is not strong enough to destroy the strong coupling. It is worth noting that it is the excited state of the chlorosome that couples to the photon and not simply the excited state of the BChl c molecule, which has an absorption peak at 667 nm (refs 65, 66), hence we can say that the strong coupling occurs between a cavity mode and a large biological system. The mixed polariton state of light-harvesting antenna and photon may present a new system for studying the light–matter interaction that is ultimately responsible for the process of photosynthesis. We have recently shown that polariton state can form an efficient energy relaxation pathway between spatially and energetically separated exciton species67, hence this demonstration of strong coupling in a biological system may allow for artificial light-harvesting devices that utilize biological components. Finally, since the density of chlorosomes within the green sulfur bacteria is high, it may be possible to strongly couple a living bacteria to a cavity mode resulting in a ‘living polariton’.

Methods

Chlorosome isolation and cavity fabrication

To prepare chlorosomes for inclusion in a microcavity, they were first purified from the C. tepidum species of green sulfur bacteria, which were cultured anaerobically and phototropically using the medium as reported in ref. 1. The cultures were incubated at 45 °C in low-intensity light (20±2 μmol m−2 s−1) and harvested at the steady state of growth, from which chlorosomes were extracted from the membrane fraction using 2 M NaI followed by sucrose gradient separation via ultracentrifugation at 135,000 × g for 16 h. The purified chlorosomes were characterized by room temperature UV–visible, fluorescence emission, circular dichroism spectroscopy and dynamic light scattering14,68. The samples were then desalted and lyophilized. The chlorosomes were then dispersed in a PVA (mw=31K–50K, 87–89% hydrolysed, Sigma Aldrich) matrix. The PVA was dissolved in deionized water at a concentration of 40 mg ml−1. The lyophilized chlorosomes were mixed in the aqueous PVA solution at a concentration of 10 mg ml−1 with a vortex mixer before the solution was passed through a PVDF filter (0.45 μm pore size).

To fabricate microcavities, the chlorosome–PVA solution was spincast onto a 40-nm-thick thermally evaporated semitransparent silver mirror to a thickness of ~205 nm. A second 40-nm-thick silver mirror was evaporated directly onto the organic layer to complete the λ/2 microcavity.

Optical experiment

The microcavity was analysed with room temperature reflection and transmission spectroscopy. The cavity was mounted on the rotation axis of goniometer and a fibre-coupled white light was focused to a 500-μm spot on the sample surface. For reflectivity measurements, the sample was rotated while the reflected light was collected by optics mounted on the rotating goniometer arm. For transmission measurements, the collection arm was fixed opposite the excitation light and only the sample was rotated. The same spot on the sample was probed in reflection and transmission with an angular resolution of 2°. The collected light was analysed with a fibre-coupled CCD spectrometer (Andor Shamrock 303i). Owing to the weak excitation, and the light collection optics being placed far from the sample, no photoluminescence is detected in reflectivity or transmission measurements.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Coles, D. M. et al. Strong coupling between chlorosomes of photosynthetic bacteria and a confined optical cavity mode. Nat. Commun. 5:5561 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6561 (2014).

Change history

21 October 2015

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

Overmann, J. The Prokaryotes 3rd edn Vol. 7, (Springer (2006).

Overmann, J., Cypionka, H. & Pfennig, N. An extremely low-light-adapted phototrophic sulfur bacterium from the Black Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 37, 150–155 (1992).

Beatty, J. T. et al. An obligately photosynthetic bacterial anaerobe from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 9306–9310 (2005).

Huh, J. et al. Atomistic study of energy funneling in the light-harvesting complex of green sulfur bacteria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 2048–2057 (2014).

Kouyianou, K. et al. The chlorosome of chlorobaculum tepidum: Size, mass and protein composition revealed by electron microscopy, dynamic light scattering and mass spectrometry-driven proteomics. Proteomics 11, 2867–2880 (2011).

Oostergetel, G., Amerongen, H. & Boekema, E. The chlorosome: a prototype for efficient light harvesting in photosynthesis. Photosynth. Res. 104, 245–255 (2010).

Frigaard, N.-U., Chew, A., Li, H., Maresca, J. & Bryant, D. Chlorobium tepidum: insights into the structure, physiology, and metabolism of a green sulfur bacterium derived from the complete genome sequence. Photosynth. Res. 78, 93–117 (2003).

Holzwarth, A. R. & Schaffner, K. On the structure of bacteriochlorophyll molecular aggregates in the chlorosomes of green bacteria. A molecular modelling study. Photosynth. Res. 41, 225–233 (1994).

Frese, R. et al. The organization of bacteriochlorophyll c in chlorosomes from Chloroflexus aurantiacus and the structural role of carotenoids and protein. Photosynth. Res. 54, 115–126 (1997).

Pšenčìk, J. et al. Lamellar organization of pigments in chlorosomes, the light harvesting complexes of green photosynthetic bacteria. Biophys. J. 87, 1165–1172 (2004).

Linnanto, J. M. & Korppi-Tommola, J. E. Investigation on chlorosomal antenna geometries: tube, lamella and spiral-type self-aggregates. Photosynth. Res. 96, 227–245 (2008).

Ganapathy, S. et al. Alternating syn-anti bacteriochlorophylls form concentric helical nanotubes in chlorosomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 106, 8525–8530 (2009).

Ganapathy, S. et al. Structural variability in wild-type and bchQ bchR mutant chlorosomes of the green sulfur bacterium Chlorobaculum tepidum. Biochemistry 51, 4488–4498 (2012).

Tang, J. K. et al. Temperature and carbon assimilation regulate the chlorosome biogenesis in green sulfur bacteria. Biophys. J. 105, 1346–1356 (2013).

Huber, V., Katterle, M., Lysetska, M. & Würthner, F. Reversible self-organization of semisynthetic zinc chlorins into well-defined rod antennae. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 3147–3151 (2005).

May, V. & Kuhn, O. Charge and Energy Transfer Dynamics in Molecular Systems Wiley (2000).

van Amerongen, H., Valkunas, L. & van Grondelle, R. Photosynthetic Excitons World Scientific (2000).

Savikhin, S. et al. Ultrafast energy transfer in light-harvesting chlorosomes from the green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium tepidum. Chem. Phys. 194, 245–258 (1995).

Psenck, J., Ma, Y.-Z., Arellano, J. B., Hála, J. & Gillbro, T. Excitation energy transfer dynamics and excited-state structure in chlorosomes of Chlorobium phaeobacteroides. Biophys. J. 84, 1161–1179 (2003).

Dostal, J. et al. Two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy reveals ultrafast energy diffusion in chlorosomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 11611–11617 (2012).

Weisbuch, C., Nishioka, M., Ishikawa, A. & Arakawa, Y. Observation of the coupled exciton-photon mode splitting in a semiconductor quantum microcavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 3314–3317 (1992).

Houdré, R. et al. Measurement of cavity-polariton dispersion curve from angle-resolved photoluminescence experiments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 2043–2046 (1994).

Tassone, F., Piermarocchi, C., Savona, V., Quattropani, A. & Schwendimann, P. Bottleneck effects in the relaxation and photoluminescence of microcavity polaritons. Phys. Rev. B 56, 7554–7563 (1997).

Reithmaier, J. P. et al. Strong coupling in a single quantum dot-semiconductor microcavity system. Nature 432, 197–200 (2004).

Peter, E. et al. Exciton-photon strong-coupling regime for a single quantum dot embedded in a microcavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 067401 (2005).

Butté, R. et al. Room-temperature polariton luminescence from a bulk GaN microcavity. Phys. Rev. B 73, 033315 (2006).

Christopoulos, S. et al. Room-temperature polariton lasing in semiconductor microcavities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 126405 (2007).

Das, A. et al. Room temperature strong coupling effects from single ZnO nanowire microcavity. Opt. Express 20, 11830–11837 (2012).

Lidzey, D. G. et al. Strong exciton-photon coupling in an organic semiconductor microcavity. Nature 395, 53–55 (1998).

Savvidis, P. G., Connolly, L. G., Skolnick, M. S., Lidzey, D. G. & Baumberg, J. J. Ultrafast polariton dynamics in strongly coupled zinc porphyrin microcavities at room temperature. Phys. Rev. B 74, 113312 (2006).

Daskalakis, K. S., Maier, S. A., Murray, R. & Kéna-Cohen, S. Nonlinear interactions in an organic polariton condensate. Nat. Mater. 13, 271–278 (2014).

Lidzey, D. G. et al. Room temperature polariton emission from strongly coupled organic semiconductor microcavities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 3316–3319 (1999).

Schouwink, P., Berlepsch, H. V., Dähne, L. & Mahrt, R. F. Observation of strong exciton-photon coupling in an organic microcavity. Chem. Phys. Lett. 344, 352–356 (2001).

Tischler, J. R., Bradley, M. S., Bulović, V., Song, J. H. & Nurmikko, A. Strong coupling in a microcavity led. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 036401 (2005).

Takada, N., Kamata, T. & Bradley, D. D. C. Polariton emission from polysilane-based organic microcavities. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 1812–1814 (2003).

Plumhof, J. D., Stöferle, T., Mai, L., Scherf, U. & Mahrt, R. F. Room-temperature Bose-Einstein condensation of cavity exciton-polaritons in a polymer. Nat. Mater. 13, 247–252 (2014).

Holmes, R. J. & Forrest, S. R. Strong exciton-photon coupling and exciton hybridization in a thermally evaporated polycrystalline film of an organic small molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 186404 (2004).

Kéna-Cohen, S., Davanço, M. & Forrest, S. R. Strong exciton-photon coupling in an organic single crystal microcavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 116401 (2008).

Kéna-Cohen, S. & Forrest, S. Room-temperature polariton lasing in an organic single-crystal microcavity. Nat. Photonics 4, 371–375 (2010).

Bellessa, J., Bonnand, C., Plenet, J. C. & Mugnier, J. Strong coupling between surface plasmons and excitons in an organic semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 036404 (2004).

Bonnand, C., Bellessa, J. & Plenet, J. C. Properties of surface plasmons strongly coupled to excitons in an organic semiconductor near a metallic surface. Phys. Rev. B 73, 245330 (2006).

Fofang, N. T. et al. Plexcitonic nanoparticles: Plasmon-exciton coupling in nanoshell-J-aggregate complexes. Nano Lett. 8, 3481–3487 (2008).

Lekeufack, D. D. et al. Core-shell gold j-aggregate nanoparticles for highly efficient strong coupling applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 253107 (2010).

Baieva, S., Ihalainen, J. A. & Toppari, J. J. Strong coupling between surface plasmon polaritons and β-carotene in nanolayered system. J. Chem. Phys. 138, 044707 (2013).

Nabiev, I. et al. Fluorescent quantum dots as artificial antennas for enhanced light harvesting and energy transfer to photosynthetic reaction centers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 7217–7221 (2010).

Carmeli, I. et al. Broad band enhancement of light absorption in photosystem I by metal nanoparticle antennas. Nano Lett. 10, 2069–2074 (2010).

Caruso, F. et al. Probing biological light-harvesting phenomena by optical cavities. Phys. Rev. B 85, 125424 (2012).

Konrad, A. et al. Manipulating the excitation transfer in photosystem I using a Fabry-Perot metal resonator with optical subwavelength dimensions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 6175–6181 (2014).

Skolnick, M. S., Fisher, T. A. & Whittaker, D. M. Strong coupling phenomena in quantum microcavity structures. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 13, 645 (1998).

Armitage, A. et al. Modelling of asymmetric excitons in organic microcavities. Synth. Met. 111–112, 377–379 (2000).

Coles, D. M. et al. Vibrationally assisted polariton-relaxation processes in strongly coupled organic-semiconductor microcavities. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 3691–3696 (2011).

Houdré, R., Stanley, R. P., Oesterle, U., Ilegems, M. & Weisbuch, C. Room-temperature cavity polaritons in a semiconductor microcavity. Phys. Rev. B 49, 16761–16764 (1994).

Hobson, P. A. et al. Strong exciton-photon coupling in a low-q all-metal mirror microcavity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 3519–3521 (2002).

Kelkar, P. V. et al. Stimulated emission, gain, and coherent oscillations in ii-vi semiconductor microcavities. Phys. Rev. B 56, 7564–7573 (1997).

Fox, M. Quantum Optics - An Introduction (Oxford Master Series) Oxford Univ. Press (2006).

Ujihara, K. Spontaneous emission and the concept of effective area in a very short optical cavity with plane-parallel dielectric mirrors. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 30, L901–L903 (1991).

Prokhorenko, V., Steensgaard, D. & Holzwarth, A. Exciton dynamics in the chlorosomal antennae of the green bacteria chloroflexus aurantiacus and chlorobium tepidum. Biophys. J. 79, 2105–2120 (2000).

Furumaki, S. et al. Absorption linear dichroism measured directly on a single light-harvesting system: the role of disorder in chlorosomes of green photosynthetic bacteria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 6703–6710 (2011).

Martiskainen, J., Linnanto, J., Aumanen, V., Myllyperkiö, P. & Korppi-Tommola, J. Excitation energy transfer in isolated chlorosomes from Chlorobaculum tepidum and Prosthecochloris aestuarii. Photochem. Photobiol. 88, 675–683 (2012).

Orf, G. S. & Blankenship, R. E. Chlorosome antenna complexes from green photosynthetic bacteria. Photosynth. Res. 116, 315–331 (2013).

Mohseni, M., Rebentrost, P., Lloyd, S. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Environment-assisted quantum walks in photosynthetic energy transfer. J. Chem. Phys. 129, 174106 (2008).

Virgili, T. et al. Ultrafast polariton relaxation dynamics in an organic semiconductor microcavity. Phys. Rev. B 83, 245309 (2011).

Schaechter, M. Encyclopedia of Microbiology 3rd edn Vol. 2, (Academic Press/Elsevier (2009).

Imhoff, J. F. Phylogenetic taxonomy of the family chlorobiaceae on the basis of 16s rRNA and FMO (Fenna-Matthews-Olson protein) gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53, 941–951 (2003).

Miller, M., Gillbro, T. & Olson, J. M. Aqueous aggregates of bacteriochlorophyll c as a model for pigment organization in chlorosomes. Photochem. Photobiol. 57, 98–102 (1993).

Balaban, T. S., Holzwarth, A. R. & Schaffner, K. Circular dichroism study on the diastereoselective self-assembly of bacteriochlorophyll cs. J. Mol. Struct. 349, 183–186 (1995).

Coles, D. M. et al. Polariton-mediated energy transfer between organic dyes in a strongly coupled optical microcavity. Nat. Mater. 13, 712–719 (2014).

Tang, J. K. H. et al. Temperature shift effect on the Chlorobaculum tepidum chlorosomes. Photosynth. Res. 115, 23–41 (2013).

Frigaard, N.-U., Li, H., Milks, K. J. & Bryant, D. A. Nine mutants of Chlorobium tepidum each unable to synthesize a different chlorosome protein still assemble functional chlorosomes. J. Bacteriol. 186, 646–653 (2004).

Acknowledgements

D.M.C., R.A.T. and J.M.S. gratefully acknowledge the Oxford Martin School for financial support. J.K.-H.T. is supported by start-up funds from Clark University. S.K.S. and A.A.G. acknowledge Defense Threat Reduction Agency Grant HDTRA1-10-1-0046. S.K.S. is also grateful to the Russian Government Program of Competitive Growth of Kazan Federal University. A.A.-G. thanks the Center for Excitonics, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science and Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Award Number DE-SC0001088. R.T.G. thanks EPSRC for a DTG Studentship and D.G.L. thanks EPSRC for continued support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K.S. and A.A.-G. conceived the experiment and provided theoretical background. J.K.-H.T., Y.Y. and Y.W. cultured the bacteria, extracted the chlorosomes and obtained the TEM image. D.M.C. fabricated the microcavity samples. Experiments were performed by R.T.G. and D.M.C. under the supervision of D.G.L., R.A.T. and J.M.S. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-2 and Supplementary References. (PDF 360 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coles, D., Yang, Y., Wang, Y. et al. Strong coupling between chlorosomes of photosynthetic bacteria and a confined optical cavity mode. Nat Commun 5, 5561 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6561

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6561

This article is cited by

-

Passive atomic-scale optical sensors for mapping light flux in ultra-small cavities

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Optical cavity-mediated exciton dynamics in photosynthetic light harvesting 2 complexes

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Probing quantum features of photosynthetic organisms

npj Quantum Information (2018)

-

Selective manipulation of electronically excited states through strong light–matter interactions

Nature Communications (2018)

-

From a quantum-electrodynamical light–matter description to novel spectroscopies

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.