Abstract

Classic psychology and economic studies argue that punishment is the standard response to violations of fairness norms. Typically, individuals are presented with the option to punish the transgressor or not. However, such a narrow choice set may fail to capture stronger alternative preferences for restoring justice. Here we show, in contrast to the majority of findings on social punishment, that other forms of justice restoration (for example, compensation to the victim) are strongly preferred to punitive measures. Furthermore, these alternative preferences for restoring justice depend on the perspective of the deciding agent. When people are the recipient of an unfair offer, they prefer to compensate themselves without seeking retribution, even when punishment is free. Yet when people observe a fairness violation targeted at another, they change their decision to the most punitive option. Together these findings indicate that humans prefer alternative forms of justice restoration to punishment alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social norms, such as fairness concerns, provide prescribed standards for behaviour that promote social efficiency and cooperation1,2,3. How humans resolve fairness transgressions has been extensively studied in the context of simple, constrained interactions4. Traditionally, people are presented with two options—engage in punitive behaviour, or do nothing. In this context, people typically respond to fairness violations with punishment5,6. However, such a narrow range of options may fail to capture alternative, preferred strategies for restoring justice that are frequently observed in everyday life. Here, we test alternative preferences for justice restoration by broadening the decision-making space to include compensatory measures in addition to punishment. Since impartiality is a core principle of many legal systems and is believed to influence judicial decision-making, we further test whether these preferences are differentially deployed depending on the perspective of the deciding agent. That is, do unaffected third parties sanction fairness violations differently than personally affected second parties?

Demonstrations of how intensely humans endorse punishment as a means of ensuring fair and equitable outcomes2 suggests that punishment is the standard response to violations of justice. Hundreds of studies using the Ultimatum Game illustrate that people are willing to incur personal monetary costs to punish fairness violations. In the Ultimatum Game, two players must agree on how to split a sum of money. First, the proposer makes an offer of how to divide the money. The responder can then either accept the offer, in which case the money is split as proposed, or reject the offer, in which case neither player receives any money7. It is well established that responders will forgo even large monetary benefits by rejecting the offer to punish the proposer for offering an unfair split8,9. In fact, extremely unfair offers are rejected around 70% of the time10.

In the real world, however, punishment is rarely the only option for restoring justice. There is a broad range of alternative responses, reflecting the idea that both the transgressor and the victim can be differentially valued depending on one’s social preferences and conceptual sense of justice. For instance, some people may prefer to compensate the victim11, or punish the transgressor such that the penalty is proportionate to the harm committed12, preferences that may prove to have powerful roles in motivating the restoration of justice. Although existence of alternative forms of justice restoration date back as far as four millennia ago13, no research that we are aware of has examined these alternatives alongside the prototypical punitive options.

The question of justice restoration is important because most legal systems are largely based on the principle that social order depends on punishment. For much of modern civilization, formal systems—such as judges and juries14,15—have been structured to mete out justice. The underlying assumption is that people make judgments differently depending on whether a fairness violation is directed towards another individual or aimed at oneself. Given the distinct asymmetries between the way people perceive themselves versus their peers16, it is thought that unaffected and putatively dispassionate third parties sanction transgressors in a less egocentric and more deliberate manner than victims17. Indeed, theorists suggest that people experience psychologically close events (for example, those experienced personally) in a detailed, concrete manner, whereas socially distant objects are construed in terms of high-level, abstract characteristics and principles18,19. Psychological distance from a transgression may therefore bias how people evaluate fairness violations and influence their subsequent preferences for restoring justice. Accordingly, we theorized that individuals would endorse different routes to justice restoration depending on whether they are the direct recipient of a fairness violation compared with when they merely observe it.

To examine alternative motivations for restoring justice and test whether individuals navigate fairness violations differently for both self and another, we developed a novel economic game that broadens the available choice space to include a range of punitive and compensatory options for restoring justice that are not present in classic experimental games. To model alternative options for justice restoration frequently observed in the real world, we not only presented participants with the opportunity to accept or reject the proposed split (as in the Ultimatum Game), but also other novel options that reflect a range of other-regarding preferences.

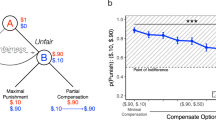

In our task, Player A has the first move and can propose a division of a $10 pie with Player B (Player A: $10−x, Player B: x, Fig. 1a). Player B can then reapportion the money by choosing from the following five options; (1) accept: agreeing to the proposed split ($10−x, x)7; (2) punish: reducing Player A’s payout to the original amount offered to Player B (x, x)20; (3) equity: equally splitting the pie so that both players receive half of the initial endowment ($5, $5)4; (4) compensate: increasing Player B’s own payout to equal Player A’s payout, thus enlarging the pie to maximizing both players’ monetary outcomes ($10−x, $10−x)21; and finally, (5) reverse: reversing the proposed split—a ‘just deserts’ motive where the perpetrator deserves punishment proportionate to the wrong committed12—so that Player A is punished and Player B is compensated (x, $10−x)22,23. See Supplementary Discussion for in-depth explanations of each option. As in many classic experimental economics games that explore trade-offs between discrete choice pairs7,24, participants were presented with only two options on any given trial, such that each option (that is, ‘compensate’, ‘equity’, ‘accept’, ‘punish’, ‘reverse’) was randomly paired with one alternative option per trial, resulting in every combination pair, for a total of 10 unique combination pairs (Fig. 1b). When making their offers, Player A was not aware which two options would be available to Player B on a given trial.

(a) The sequential game. Player A can make any offer to Player B. Here we illustrate all the options that Player B has to reapportion the money after being offered a split of $9/$1. On each round, however, Player B is presented with a forced choice between two options (for example, compensate versus equity, compensate versus accept, compensate versus punish, and so on) for a total of 10 pairwise comparisons. Options were randomly paired and presented across the experiment. We focused our analysis on unfair offers, splits of $6/$4 through $9/$1. (b) An example of a round where Player A offers Player B $1. In this case Player B is then presented with the option to either increase their own payout without decreasing Player A’s payout (compensate), or reverse the payouts such that Player A receives $1 and Player B receives $9 (reverse).

We find that although decades of research demonstrate that individuals consistently retaliate against those who behave unfairly, when alternative options for dealing with fairness violations are made available, these assumedly robust preferences to punish another are not actually preferred when offered alongside other, non-punitive options. However, when tasked with making the same decision on behalf of someone else who has experienced a fairness violation, individuals modify their responses and apply the harshest form of punishment to the transgressor. Together these results challenge our current understanding of social preferences and the emphasis placed on punitive behaviour.

Results

Preferences for justice restoration extend beyond punishment

Figure 2a shows choice behaviour (N=112; 42 males, mean age 20.8±2.11) for moderately unfair offers  and highly unfair offers

and highly unfair offers  in Experiment 1. We compute endorsement rates by the frequency an option is selected, such that each option’s endorsement rate is out of 100% (number of times an option is selected/number of times the option is presented during the experiment). That is, we calculate the number of times ‘accept’ is chosen when paired with every possible alternative option, and did the same for ‘punish’, ‘compensate’, ‘equity’ and ‘reverse’. Strikingly, across all offer types, participants least chose the options ‘accept’ and ‘punish’ (10% and 16% endorsement rate, respectively; Supplementary Table 1)—the two options most similar to those in the traditional Ultimatum Game. Instead, participants most preferred the option ‘compensate’, choosing to increase their own payout and apply no punishment to Player A (92% endorsement rate; Supplementary Table 1). This preference remained robust even when participants were offered a highly unfair split of

in Experiment 1. We compute endorsement rates by the frequency an option is selected, such that each option’s endorsement rate is out of 100% (number of times an option is selected/number of times the option is presented during the experiment). That is, we calculate the number of times ‘accept’ is chosen when paired with every possible alternative option, and did the same for ‘punish’, ‘compensate’, ‘equity’ and ‘reverse’. Strikingly, across all offer types, participants least chose the options ‘accept’ and ‘punish’ (10% and 16% endorsement rate, respectively; Supplementary Table 1)—the two options most similar to those in the traditional Ultimatum Game. Instead, participants most preferred the option ‘compensate’, choosing to increase their own payout and apply no punishment to Player A (92% endorsement rate; Supplementary Table 1). This preference remained robust even when participants were offered a highly unfair split of  (Fig. 2a).

(Fig. 2a).

We compute endorsement rates by the frequency an option is selected from all available trials, such that each option’s endorsement rate is out of 100%. (a) Results (N=112) reveal that compensation is the most preferred choice, even when offered highly unfair splits. (b) The choice pair compensate versus reverse (game structure illustrated in Fig. 1b) equates for Player B’s fiscal efficiency, such that Player B can both compensate himself and punish Player A at no cost. Even when punishment is free, participants significantly prefer to compensate themselves and apply no punishment to Player A; Pearson’s χ2=9, 1 df, P=0.003, ϕ=0.15.

Since the choice pair ‘compensate’ versus ‘reverse’ controls for Player B’s monetary benefit—that is, after receiving a highly unfair spilt of  choosing compensate

choosing compensate  or reverse

or reverse  results in the exact same monetary payout to Player B ($9)—we can use this choice pair to directly test other-regarding preferences while controlling for Player B’s fiscal efficiency. Results reveal that when responding to unfair offers, participants prefer to compensate rather than reverse, even though punishment is free (Pearson’s χ2=9, 1 df, P=0.003, ϕ=0.15, Fig. 2b). In other words, despite the available option to maximize one’s payout while simultaneously applying punishment to Player A (selecting ‘reverse’), participants preferred to maximize their payoff and not apply any punishment to Player A. Although most previous research has focused on punishment3 as the primary method of restoring justice, these findings illustrate that when possible, people actually prefer compensation to punishment.

results in the exact same monetary payout to Player B ($9)—we can use this choice pair to directly test other-regarding preferences while controlling for Player B’s fiscal efficiency. Results reveal that when responding to unfair offers, participants prefer to compensate rather than reverse, even though punishment is free (Pearson’s χ2=9, 1 df, P=0.003, ϕ=0.15, Fig. 2b). In other words, despite the available option to maximize one’s payout while simultaneously applying punishment to Player A (selecting ‘reverse’), participants preferred to maximize their payoff and not apply any punishment to Player A. Although most previous research has focused on punishment3 as the primary method of restoring justice, these findings illustrate that when possible, people actually prefer compensation to punishment.

In a second experiment, Player Bs were presented with varying splits of a $1 endowment from Player A, ranging from moderately unfair  to highly unfair

to highly unfair  , reflected through 10 cent increments. As in Experiment 1, participants (N=97, Experiment 2a) did not prefer traditional Ultimatum Game options to ‘accept’ the offer or to ‘punish’ Player A for proposing an unfair split, and instead the strongest preference was to compensate (84% endorsement rate of ‘compensate’ across all offer types, Supplementary Table 2a). Again, for unfair offers, the choice pair compensate versus reverse reveals that even when punishment is free, individuals still prefer to compensate and abstain from punishing Player A (Pearson’s χ2=7.7, 1 df, P=0.005, ϕ=0.14). Together, these findings indicate that when given the option for alternative forms of justice restoration, compensation of the victim is strongly preferred to punishment of the transgressor.

, reflected through 10 cent increments. As in Experiment 1, participants (N=97, Experiment 2a) did not prefer traditional Ultimatum Game options to ‘accept’ the offer or to ‘punish’ Player A for proposing an unfair split, and instead the strongest preference was to compensate (84% endorsement rate of ‘compensate’ across all offer types, Supplementary Table 2a). Again, for unfair offers, the choice pair compensate versus reverse reveals that even when punishment is free, individuals still prefer to compensate and abstain from punishing Player A (Pearson’s χ2=7.7, 1 df, P=0.005, ϕ=0.14). Together, these findings indicate that when given the option for alternative forms of justice restoration, compensation of the victim is strongly preferred to punishment of the transgressor.

Second and third party preferences for justice restoration

To test whether being directly affected by a fairness violation influences decisions to restore justice, we also examined participants’ behaviour when they acted as a non-vested third party (Player C), observing interactions between Players A and B (N=261, Experiment 2b). That is, participants were asked to make decisions on behalf of another player such that payoffs would be paid to Players A and B and not to themselves. Unlike in the ‘Self’, second-party condition in which participants played the game as Player B (Experiments 1 and 2a), these ‘Other’, third-party decisions were non-costly and non-beneficial. Similar to decisions made in the Self condition, Player Cs (Other condition) show little preference to ‘accept’ the offer, or to ‘punish’ Player A for proposing an unfair split to Player B (Supplementary Table 2b).

Although individuals chose to compensate oneself and another at the same rate when the offer was relatively fair  (McNemar’s χ2=1.2, 1 df, P=0.27), we found that when responding to unfair offers, Player Cs selected ‘reverse’—the option that both compensates Player B and punishes Player A—significantly more often than Player Bs did for themselves (choice pair compensate/reverse: McNemar’s χ2=13.5, 1 df, P<0.001, ϕ=0.14; Supplementary Fig. 2). In other words, although participants did not show preferences for punishing Player A when directly affected by a fairness violation (that is, as a second party), when observation of a fairness violation targeted at another (that is, as a third party), participants significantly increased their retributive responding.

(McNemar’s χ2=1.2, 1 df, P=0.27), we found that when responding to unfair offers, Player Cs selected ‘reverse’—the option that both compensates Player B and punishes Player A—significantly more often than Player Bs did for themselves (choice pair compensate/reverse: McNemar’s χ2=13.5, 1 df, P<0.001, ϕ=0.14; Supplementary Fig. 2). In other words, although participants did not show preferences for punishing Player A when directly affected by a fairness violation (that is, as a second party), when observation of a fairness violation targeted at another (that is, as a third party), participants significantly increased their retributive responding.

Since one motive for exploring justice restoration was to investigate whether broadening the decision-making space (to include a plurality of options) affects choice behaviour, we ran four additional experiments (analysed together, see Supplementary Materials) where all five options were available on every trial. In these studies, participants were offered splits of $1 and made decisions both for themselves and on behalf of others in a within-subjects design. That is, participants made decisions both when they were personally affected by a fairness violation (as Player B; Self condition), and also on behalf of another player who was affected by a fairness violation (as Player C; Other condition).

As with our previous experiments, participants (N=540) demonstrated strong preferences to ‘compensate’ (42% endorsement rate out of 100% across all offer types, Supplementary Fig. 3A), and did not preferentially choose to ‘accept’ the offer or ‘punish’ Player A (10% and 3% endorsement rate, respectively) when deciding for themselves. However, as the split became increasingly unfair, participants were more likely to incorporate punitive measures17, almost doubling their endorsement of the ‘reverse’ option in which they simultaneously compensated themselves and punished Player A (15% endorsement of ‘reverse’ for relatively fair offers, compared with 30% for highly unfair offers; Cochran’s Q χ2=234, 3 df, P<0.001, Fig. 3a; analyses across all four experiments25). Despite this, even when offered a highly unfair split  , participants still preferred the least punitive and most compensatory option ‘compensate’ (43% endorsement rate; Cochran’s Q χ2=562.2, 4 df, P<0.001, Fig. 3a).

, participants still preferred the least punitive and most compensatory option ‘compensate’ (43% endorsement rate; Cochran’s Q χ2=562.2, 4 df, P<0.001, Fig. 3a).

(a) Overall choice preferences (n=540) for relatively fair offers ($0.60, $0.40) compared with highly unfair offers ($0.90, $0.10) in the Self condition: participants exhibit strong preferences for the option to compensate in both fair and unfair trials; χ2=562.2, 4 df, P<0.001. However, preferences for retributive action become stronger when the offer is highly unfair; χ2=234, 3 df, P<0.001. (b) Unfair offers ($0.90, $0.10 split) reveal that participants have significantly stronger preferences for retributive behaviour (reverse option) when making decisions for another than they do for the self; χ2=20.2, 1 df, P<0.001, ϕ=0.13. (c) Fair offers (0.60, 0.40 split) reveal similar choice preferences for Self and Other conditions; all χ2s<1.16, all Ps>0.3; except for punish χ2=4.67, 1 df, P=0.03. ***P<0.001.

The participants’ perspective (that is, Self versus Other condition) shifted their preferences only when the offer was highly unfair. In the Other condition, participants chose to ‘reverse’ the players’ payouts significantly more than any other option (43% endorsement rate; Cochran’s χ2=622.2, 4 df, P<0.001; Fig. 3b, see Supplementary Fig. 3B for more details), and significantly more than they did in the Self condition (McNemar χ2=20.2, 1 df, P<0.001, ϕ=0.13, Fig. 3b). This result replicated Experiment 2, however, here participants were making decisions both as Player B and Player C (a within-subject design). Individuals who did not endorse punitive measures when deciding for themselves changed their decisions to the most retributive option after observing a fairness violation targeted at another. In contrast, there were no significant differences between choices for relatively fair offers in the Self and Other conditions (all χ2s<1.16, all Ps>0.3; except for punish χ2=4.67, 1 df, P=0.03 Fig. 3c).

Discussion

Traditionally, research has focused on punishment as the preferred response to a perceived injustice, leading to the specious assumption that people prefer to punish when righting a wrong3,14,24,26,27. While these studies conclude that punishment is the standard response to fairness violations, it appears that these preferences to punish may be due to a limited choice set where participants do not have the option to select from non-punitive alternatives that satisfy other preferences (for example, for equity). Here we demonstrate that when given the option to respond non-punitively to fairness violations, people derive greater utility from responding in a positive manner than they do in a punitive manner. That is, people prefer alternative forms of justice restoration, choosing compensation over punitive or retributive options. These findings fit within an emerging body of research exploring how prosocial options—like rewarding cooperation28 so long as punishment remains a viable option29—can be more effective in sustaining cooperation than punishment alone.

It is possible that participants chose to compensate and not punish because they prefer to maximize their own payment (rather than decrease the transgressor’s payment) and because they are averse to inequality. While these are both important motivations for justice restoration, they may not necessarily be mutually exclusive. An important next question is whether people still choose to compensate even if compensation does not match Player A’s payout (that is, partial compensation). Future work designed to qualitatively identify relative preferences between compensation and equality will help decipher how—and when—people trade off compensation for equality.

There are of course instances when punishment becomes a more attractive response than non-punitive options. Depending on the options punishment is juxtaposed against, deciding to punish may provide the greatest utility. For example, when offered alongside the option to accept an unfair offer, punishment (for example, equalizing both players’ payoffs as well as reducing the payoff of the transgressor) is the most preferred option in our experiments and in the abundant research employing the Ultimatum Game. Combining our findings with prior research on punishment clearly demonstrates that the preference for punishment can be differentially valued depending on the landscape of options. Punishment, compensation, equity, and other alternatives to justice restoration may all provide varying degrees of utility depending on the alternative available options and the extent of the fairness violation in the first place. However, the evidence that people exhibit strong preferences to compensate when responding to fairness violations suggests that the current emphasis on punishment fails to capture other important alternatives for justice restoration.

Interestingly however, when responding to a fairness violation on behalf of another, individuals shift their preferences for restoring justice to include the most punitive and retributive measures. That individuals prefer more punitive options when deciding on behalf of another but not for oneself illustrates that context can dramatically alter the attractiveness of punishment as a measure of justice restoration. One possible explanation for the observed differences in choice behaviour between Self and Other is that deciding for another entails greater psychological distance. Increasing psychological distance—including social distance—emphasizes higher-level, abstract characteristics in the perception, experience and evaluation of situations or objects19,30. When deciding on behalf of another, people may be attending to schematic representations of justice—abstract ideological values such as ‘justice as fairness’31—which emphasizes the application of known social norms to right a perceived injustice. In this case, punitive responding increases because people can easily rely on the straightforward prescriptions of punishing as a means to restore justice. On the other hand, when making decisions for oneself, events may be construed in terms of low-level, concrete and essential features, including the possibility of monetary gain. When directly experiencing a fairness violation, people may be ignoring the straightforward prescriptions of justice (to punish), instead concretely evaluating each option and its consequences. Thus, the focus is less on punishing the transgressor and more on compensating for oneself.

Here we illustrate that when presented with alternative options for restoring justice, people do not prefer to punish. We also demonstrate that people respond more punitively on behalf of others than they do for themselves. The findings that victims prefer compensation over punishment could inform how the legal system approaches the punishment of transgressors. How to restore justice is a complex question, and while this research is only an initial step, it highlights the myopia of our understanding to date, and the critical importance of considering alternative means of making what was wrong, right.

Methods

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 was run at the laboratory of the Center for Experimental Social Science (CESS) at New York University. One hundred and twelve participants participated, drawn from the general undergraduate population and recruited through e-mail solicitations. Each experimental session lasted ~1 h. All experiments were approved by New York University’s Committee on Activities Involving Human Subjects and all participants completed a consent form before starting the experiment.

We utilized a pairwise comparison design that allowed us to directly contrast every choice pair (as in the Ultimatum Game, Fig. 1b). We recruited as many as 22 participants during one session, randomly assigning half of the participants to play as Player A and the other half to play as Player B for the duration of the entire experiment. All participants were paid an initial $10 show-up fee and an additional bonus depending on their choices (ranging from $1 to $9), which falls within the traditional monetary incentive structure for Ultimatum Games32. The instructions were read out loud so that all participants were collectively made aware of the rules. Full instructions can be found in the Supplementary Materials. On each trial, participants were randomly and anonymously paired with other participants in the room, resulting in 70 one-shot games. On every trial, all Player As were endowed with $10 and were told to make a split in whatever way he or she sees fit with Player B, so long as it is in whole dollar increments. Player B was then presented with options to reapportion the money. Altogether there were five options, however, only two of these options were presented at one time on any given trial (Fig. 1b). Participants were made aware that options to reapportion the money would be randomly paired and presented on each trial. Furthermore, participants were told that one trial would be randomly selected to be paid out and that half of the time the trial would be paid out according to Player A’s split (like a dictator game), and half the time according to the decision by Player B to reapportion the money (see Supplementary Methods for more task details). Although Player A could choose to split the money in whatever way they saw fit, our aim was to understand social preferences for restoring justice, and so we restricted our analysis to unfair splits of $10, ranging from moderately unfair  to highly unfair

to highly unfair  .

.

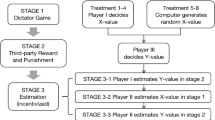

Experiments 2–6

Participants were recruited from the United States using the online labour market Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT)33,34,35,36). Participants played anonymously over the Internet and were not allowed to participate in more than one experimental session. On each trial, participants (Player B) were paid an initial participation fee of $0.50 and an additional bonus depending on their choices (ranging from $0.10 to $0.90). Across all experiments, participants were first presented with a standard digital consent form, which explained the general procedure, known risks (none), confidentiality, compensation and their rights. They could only partake in the study once they agreed to the consent form.

To ensure task comprehension, participants had to correctly complete a quiz following the instructions. Only after they correctly completed the quiz could participants begin the task. Participants were then told to place their hands on the keyboard on the following keys: S, D, F, H, J, and a timer counted down from five before the task started. On each trial, the options ‘compensate’, ‘equity’, ‘accept’, ‘punish’ and ‘reverse’ (labelled in analyses and here, but not presented to participants; see Supplementary Fig. 4) were displayed in a different order. After completing the task, participants were explicitly probed on their strategies when the offer was relatively fair  and when the offer was highly unfair

and when the offer was highly unfair  , for both the Self and Other conditions. That is, participants were asked ‘in your own words please describe your strategy for a scenario when Player A kept $0.60 and offered $0.40 to you’. See Supplementary Materials for a sampling of participants’ strategies.

, for both the Self and Other conditions. That is, participants were asked ‘in your own words please describe your strategy for a scenario when Player A kept $0.60 and offered $0.40 to you’. See Supplementary Materials for a sampling of participants’ strategies.

Unlike the experiments run in the laboratory, in the experiments run through AMT, we restricted offers from Player A (in reality, predetermined offers from a computer) to varying levels of unfairness, ranging from moderately unfair  to highly unfair

to highly unfair  , reflected through $0.10 increments. This was done primarily because we were interested in how people resolve fairness transgressions.

, reflected through $0.10 increments. This was done primarily because we were interested in how people resolve fairness transgressions.

Differences in task structure for experiments 2–6

Experiment 2 was a pairwise comparison of each choice pair (Fig. 1b). Participants (N=358) played the task either as Player B (Self condition; N=97) or as Player C (Other condition; N=261), a between-subjects design. Participants were only instructed about the condition they were in, such that the instructions either explained that participants were to make decisions for themselves and Player A (Self condition), or on behalf of two other Players (Other condition). Participants were able to make an additional payout based on their choices if they completed the Self condition. For participants who completed the Other condition, they did not make an additional bonus but were paid for the time taken to complete the task.

Like in Experiment 1, on each trial, participants were presented with only two options. For example, after being offered an unfair split, Player B only observed two options (for example, compensate versus equity, compensate versus accept, compensate versus punish, compensate versus reverse, equity versus accept, equity versus punish, and so on). Thus, for every offer type ( —

— ), participants saw all possible pairwise comparisons (that is, 10 pairs for each offer type, and four different offer types, resulting in 40 anonymous, one-shot games in total). Trials were randomly presented to participants.

), participants saw all possible pairwise comparisons (that is, 10 pairs for each offer type, and four different offer types, resulting in 40 anonymous, one-shot games in total). Trials were randomly presented to participants.

In Experiments 3–6, participants played the task as both Player B and Player C. This within-subject design allowed us to explore each individual’s choices across conditions, Self and Other. Although Experiments 3–6 were quite similar, there were small differences between the tasks which are enumerated here. In Experiment 3, Self and Other trials were presented in discrete blocks, with the Self condition always presented first and the Other condition presented second. However, to ensure that there were no order effects and that participants were not anchoring their decisions according to the decisions made in the first block (Self condition), Experiments 4–6 randomly presented the trials such that Self and Other trials were randomly interleaved across the experiment. In Experiment 3, reaction times were collected with a mouse, whereas in Experiments 4–6, reaction times were collected using the keyboard (button presses). Reaction time data were similar regardless of whether participants used a mouse or a keyboard: across all four Experiments, participants were faster to decide for another than they were for themselves (see reaction time data in Supplementary Materials). In Experiment 4, each participant was presented with a random ordering of trials. In other words, no participant saw the same order of offer types. In Experiment 5, all participants were presented with the same randomized set of trials. That is, AMT presented the same order of trials (previously determined by an algorithm to randomly interleave offer types and conditions) to all participants. Experiment 6 followed the same structure as Experiment 5, with the only difference being that blank profile pictures were added to the instructions to further delineate the roles of all the players.

Additional information

How to cite this article: FeldmanHall, O. et al. Fairness violations elicit greater punishment on behalf of another than for oneself. Nat. Commun. 5:5306 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6306 (2014).

References

Falk, A., Fehr, E. & Fischbacher, U. Testing theories of fairness—Intentions matter. Games Econ. Behav. 62, 287–303 (2008).

Fehr, E. & Fischbacher, U. Why social preferences matter—The impact of non-selfish motives on competition, cooperation and incentives. Econ. J. 112, C1–C33 (2002).

Fehr, E., Fischbacher, U. & Gachter, S. Strong reciprocity, human cooperation, and the enforcement of social norms. Hum. Nature 13, 1–25 (2002).

Fehr, E. & Schmidt, K. M. A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Q. J. Econ. 114, 817–868 (1999).

Herrmann, B., Thoni, C. & Gachter, S. Antisocial punishment across societies. Science 319, 1362–1367 (2008).

Fowler, J. H. Altruistic punishment and the origin of cooperation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 7047–7049 (2005).

Guth, W., Schmittberger, R. & Schwarze, B. An experimental-analysis of ultimatum bargaining. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 3, 367–388 (1982).

Cameron, L. A. Raising the stakes in the ultimatum game: Experimental evidence from Indonesia. Econ. Inq. 37, 47–59 (1999).

Slonim, R. & Roth, A. E. Learning in high stakes ultimatum games: an experiment in the Slovak Republic. Econometrica 66, 569–596 (1998).

Camerer, C. Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction Russell Sage Foundation; Princeton University Press (2003).

Weitekamp, E. Reparative Justice: towards a victim oriented system. Eur. J. Criminal Policy Res. 1, 70–93 (1993).

Carlsmith, K. M., Darley, J. M. & Robinson, P. H. Why do we punish? Deterrence and just deserts as motives for punishment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83, 284–299 (2002).

Gurney, O. R. & Kramer, S. N. Two Fragments of Sumerian Laws University of Chicago Press (1965).

Fehr, E. & Fischbacher, U. Third-party punishment and social norms. Evol. Hum. Behav. 25, 63–87 (2004).

Smith, A. The Theory of Moral Sentiments A. Millar (1759).

Nisbett, R. E., Legant, P. & Marecek, J. Behavior as seen by actor and as seen by observer. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 27, 154–164 (1973).

Fehr, E. & Fischbacher, U. Social norms and human cooperation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 8, 185–190 (2004).

Ledgerwood, A., Trope, Y. & Liberman, N. Flexibility and consistency in evaluative responding: the function of construal level. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 43, 257–295 (2010).

Trope, Y. & Liberman, N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 117, 440–463 (2010).

Bolton, G. E. & Zwick, R. Anonymity versus punishment in ultimatum bargaining. Games Econ. Behav. 10, 95–121 (1995).

Lotz, S., Okimoto, T. G., Schlosser, T. & Fetchenhauer, D. Punitive versus compensatory reactions to injustice: Emotional antecedents to third-party interventions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 47, 477–480 (2011).

Pillutla, M. M. & Murnighan, J. K. Unfairness, anger, and spite: Emotional rejections of ultimatum offers. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 68, 208–224 (1996).

Straub, P. G. & Murnighan, J. K. An experimental investigation of ultimatum games—information, fairness, expectations, and lowest acceptable offers. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 27, 345–364 (1995).

Fehr, E. & Gachter, S. Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 90, 980–994 (2000).

Schimmack, U. The ironic effect of significant results on the credibility of multiple-study articles. Psychol. Methods 17, 551–566 (2012).

Henrich, J. et al. ‘Economic man’ in cross-cultural perspective: behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Behav. Brain Sci. 28, 795–815 (2005).

Rand, D. G. & Nowak, M. A. The evolution of antisocial punishment in optional public goods games. Nat. Commun. 2, 434 (2011).

Rand, D. G., Dreber, A., Ellingsen, T., Fudenberg, D. & Nowak, M. A. Positive interactions promote public cooperation. Science 325, 1272–1275 (2009).

Andreoni, J., Harbaugh, W. & Vesterlund, L. The carrot or the stick: rewards, punishments, and cooperation. Am. Econ. Rev. 93, 893–902 (2003).

Ledgerwood, A., Trope, Y. & Chaiken, S. Flexibility now, consistency later: psychological distance and construal shape evaluative responding. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 99, 32–51 (2010).

Rawls, J. Theory of Justice 38–52Harvard University (1994).

Camerer, C. T. & Thaler, R. H. Anomalies: ultimatums, dictators and manners. J. Econ. Behav. Perspect. 9, 209–219 (1995).

Mason, W. & Suri, S. Conducting behavioral research on Amazon's Mechanical Turk. Behav. Res. Methods 44, 1–23 (2012).

Horton, J. J., Rand, D. G. & Zeckhauser, R. J. The online laboratory: conducting experiments in a real labor market. Exp. Econ. 14, 399–425 (2011).

Paolacci, G., Chandler, J. & Ipeirotis, P. G. Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgm. Decis. Making 5, 411–419 (2010).

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T. & Gosling, S. D. Amazon's mechanical turk: a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 6, 3–5 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dean Mobbs and Tim Dalgleish for their early help and support with this research. This research is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Aging.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.F.H. designed the experiments in consultation with E.A.P. and P.S.H. O.F.H. and P.S.H. carried out the experiments. O.F.H. ran the statistical analyses, and O.F.H., P.S.H., J.J.V.B. and E.A.P. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-7, Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary References (PDF 1326 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

FeldmanHall, O., Sokol-Hessner, P., Van Bavel, J. et al. Fairness violations elicit greater punishment on behalf of another than for oneself. Nat Commun 5, 5306 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6306

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6306

This article is cited by

-

Infringers’ willingness to pay compensation versus fines

European Journal of Law and Economics (2022)

-

Emotion prediction errors guide socially adaptive behaviour

Nature Human Behaviour (2021)

-

A Naturalistic Study of Norm Conformity, Punishment, and the Veneration of the Dead at Texas A&M University, USA

Human Nature (2021)

-

Direct and indirect punishment of norm violations in daily life

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Children punish third parties to satisfy both consequentialist and retributive motives

Nature Human Behaviour (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.