Abstract

Lithium–oxygen batteries have the potential needed for long-range electric vehicles, but the charge and discharge chemistries are complex and not well understood. The active sites on cathode surfaces and their role in electrochemical reactions in aprotic lithium–oxygen cells are difficult to ascertain because the exact nature of the sites is unknown. Here we report the deposition of subnanometre silver clusters of exact size and number of atoms on passivated carbon to study the discharge process in lithium–oxygen cells. The results reveal dramatically different morphologies of the electrochemically grown lithium peroxide dependent on the size of the clusters. This dependence is found to be due to the influence of the cluster size on the formation mechanism, which also affects the charge process. The results of this study suggest that precise control of subnanometre surface structure on cathodes can be used as a means to improve the performance of lithium–oxygen cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The aprotic Li–O2 battery is of great interest because of the new concept that it employs for electrical energy storage and the possibility for achieving very high energy densities needed for long-range electric vehicles1,2,3,4,5. The Li–O2 battery is based on the use of an electrochemical transformation, that is, formation of Li–O bonds during discharge and breaking of the bonds during charge to store and release electrical energy. A porous oxygen cathode is used to store the solid products generated from the reaction of Li cations with O2 during discharge. The exact role of electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction during discharge and oxygen evolution during charge is not well established, although there have been numerous studies. These studies included different carbons6,7,8 and polycrystalline metal surfaces such as nanoporous gold9,10, all of which have a variety of active sites. Other studies have reported supported nanoparticles as electrocatalysts in Li–O2 cells11,12,13,14,15. In addition, during the deposition process of nanoparticles it is possible that small clusters may also be present that are acting as electrocatalysts as has been found in surface reactions involving gold clusters16. ‘Catalysts’ for the oxygen reduction reaction only play a role if the discharge product is soluble allowing the reactants, O2 and Li+, access to catalytic sites. If the discharge product is not soluble then catalysts will not play a role in the discharge process17,18,19.

Recent advances in the capabilities for depositing metal clusters of exact size and composition provide a new technique to create carefully controlled cathode materials for obtaining insight into the role of specific active sites in Li–O2 batteries and understanding the role of catalysis. Previously, we have shown that size-selective subnanometre metal atom clusters can be stabilized for heterogeneous catalysis and have dramatically different catalytic properties compared with larger nanoparticles or bulk metal surfaces20,21,22. Size-selective clusters have exhibited superior selectivity and unmatched activity for several key catalytic reactions, such as the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane (Pt6–8) (ref. 20) and selective oxidation of propylene (Ag3, Au5–8) (refs 21, 22). In addition, our recent work has shown that Pd6 and Pd17 clusters are stable and highly active for electrocatalytic water splitting, while Pd4 clusters show no activity at all23. Thus, it is of interest to use cathode materials on the basis of supported size-selected metal clusters in Li–O2 cells to determine whether surface species at the subnanometre size level play a role in the discharge and charge process.

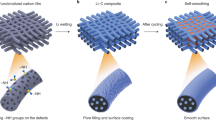

To use subnanometre clusters in a Li–O2 cell for study of their properties during discharge and charge, it is necessary to eliminate defect sites in the carbon cathode from participating in the electrochemical process. We have recently accomplished this through the use of an atomic layer deposition (ALD) coating of aluminium oxide on the carbon surface15. The ALD was used to deposit a thin film of alumina on the carbon, which covers regions of the defect sites because of preferential attachment there. Palladium nanoparticles (2–5 nm) were subsequently deposited using ALD on the partially alumina-coated carbon surfaces and tested in Li–O2 cells. The results from this study15 showed that the alumina coating prevents decomposition of the ether solvent (tetraglyme) from the surface, a problem with Li–O2 cells, and also results in a very low charge potential when the Pd nanoparticles are used. However, the non-uniformity of the Pd nanoparticles prevented a clear determination of their exact role in obtaining the low charge potential. In addition, other electrolyte stability issues prevented cycling for more than about 12 cycles.

In the study reported here, we have deposited three different sizes of Ag clusters (3, 9 and 15 atoms) on a carbon cathode with an alumina coating on the defect sites. By combining these well-defined cluster sizes with passivation of carbon defect sites, the resulting cathode architecture provides for a well-characterized material for studying the dependence of discharge on catalyst, which has not been possible in any of the previous studies on Li–O2 batteries. In this paper, we show, using various characterization techniques, that the silver cluster size has a surprising effect on the morphology of the discharge product and that this is due to the clusters acting as active sites to promote different types of formation mechanisms, which gives rise to differing building blocks that make up the mesoscale assemblies of the lithium peroxide-based discharge product.

Results

Cathode materials

Conductive graphitized carbon (GC) was used as the catalyst support material. The carbon surface was partially coated with Al2O3 by ALD, which passivates carbon defect sites15 and is about 0.5 nm thick. At this thickness, coated carbon is still electrically conductive and can act as a support for the silver clusters. Size-selected Agn (n=3, 9, 15) clusters were soft landed on the alumina-coated GC under identical deposition and coverage conditions (corresponding to 12.35% atomic monolayer equivalent, ML, of an ideal smooth surface). The principle deposition technique of size-selected cluster is described elsewhere20,21,22,23 (also see Methods).

The size-selected clusters were characterized as to size and composition on the cathode surface. The coverage of soft-landed clusters was kept low enough (12.35% ML) to prevent agglomeration at room temperature. Evidence for this comes from transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the Ag15 clusters in Fig. 1, which shows 15 atom clusters (Fig. 1c). The total number of Ag atoms deposited was the same in each case, providing a basis for direct comparison of performance of all cluster sizes. Owing to the same number of atoms deposited, the resulting density of clusters will be different; there will be a higher density of smaller clusters and smaller density of larger clusters. Thus, the results for the three cathodes prepared in this manner provide a precise method to investigate the effect of the metal cluster size and density on the discharge and charge processes in a Li–O2 cell.

(a) Low-magnification TEM image of Ag15 clusters on an amorphous carbon film showing uniform size and distribution of the clusters (scale bar, 5 nm). (b) Medium-magnification TEM image of Ag15 clusters (arrows) on an Al2O3-coated carbon particle before first discharge. Occasionally, agglomeration of Ag15 clusters (large circle) is observed (scale bar, 2 nm). (c) High-resolution TEM image of an Ag15 cluster on an Al2O3-coated carbon surface (scale bar, 1 nm).

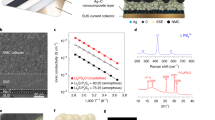

The performance of the three silver clusters on the alumina-passivated GC cathode as well as the alumina-passivated GC cathode itself was examined using a Swagelok-type cell15 composed of a lithium metal anode, electrolyte (1 M LiCF3SO3 in tetraethylene glycol dimethyl ether (TEGDME) impregnated into a glass fibre separator) and a porous cathode (13 mm diameter). A relatively low current density of 100 mA g−1 was used for both discharge and charge. Since the same number of Ag atoms are deposited on each cathode surface and the clusters have nearly the same number of surface atoms, the current density will be the same for all three cathodes. Figure 2 shows voltage profiles recorded during the first and second discharge/charge cycles obtained for the three cathode architectures with the three different cluster sizes (Ag3, Ag9, Ag15). The discharge product from the Ag15-based cathode shows significantly lower charge overpotential (~0.7 eV) compared with that from Ag3 and Ag9 as well as a cathode with no clusters added (see Supplementary Fig. 1). The Li–O2 cell based on the Ag15 clusters lasts for about 10 cycles before failing, while the others degrade much faster. The cycling of the Ag15 cell for ~10 cycles is evidence for the chemical stability of subnanometre Ag clusters. During charge, the Ag clusters will be oxidized due to their low oxidation potential, but not necessarily become silver oxide since the oxidized clusters are not likely to react with Li2O2 and only react with oxygen over time due to slow reaction kinetics. There are several possible causes for the Ag15 cluster cell degradation besides gradual oxidation of the clusters including electrolyte decomposition24,25,26,27,28,29 and lithium anode corrosion30.

Characterization of discharge products

The discharge products resulting from the three cluster sizes were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and TEM imaging and were found to dramatically depend on the Ag cluster size. The SEM images in Fig. 3 show the carbon cathode after discharge to 2.5 V for the first cycle. The SEM images reveal that the discharge product resulting from the Ag3 cluster-based cathode is film-like. In contrast the discharge product of the Ag9-based cathode is largely toroid-like with rough surfaces, while that of the Ag15-based cathode is characterized by toroids with relatively smooth surfaces. The Ag9 toroids are smaller than the Ag15 toroids (~500 nm versus ~1,000 nm) with the same discharge capacity. Toroids have been found in the discharge product by others in Li–O2 cells31,32,33,34. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns in Fig. 3d are consistent with Li2O2 in all three cases. The discharge capacities for the first cycle after discharge to 2.5 V in Fig. 2d also show that the Ag15-based cathode capacity (~3,500 mAh g−1) is much larger than those of the Ag3- and Ag9-based cathodes (~2,400 mAh g−1).

(a) on Ag3-based cathode material (scale bar, 1 μm); (b) on Ag9-based cathode material (scale bar, 1 μm; scale bar of inset image, 250 nm); and (c) on Ag15-based cathode material (scale bar, 1 μm; scale bar of inset image, 500 nm). (d) XRD patterns for the three discharge products from the three cathode materials. The cells are discharged to 2.5 V in all cases.

The lithium peroxide discharge product on the cathode was further probed by TEM imaging and the results from the first discharge to 2.5 V are shown in Fig. 4. The TEM images show several distinct building blocks that make up the discharge products. A TEM image of a toroid from the discharge product based on the cathode with Ag15 clusters is shown in Fig. 4c and indicates the presence of both nanosized grains (nanoparticles of ~10 nm size) and amorphous regions suggesting that the toroids are nanocrystalline, that is, made up of grains and grain boundaries. A higher-resolution TEM image of the Ag15 product in Fig. 4d also shows amorphous and crystalline regions. The electron diffraction pattern of the Ag15 product (Fig. 4d) is consistent with the presence of crystalline Li2O2.

(a) On Ag3-based cathode material (scale bar, 200 nm); (b) on Ag9-based cathode material (scale bar, 200 nm); (c) on Ag15-based cathode material (scale bar, 20 nm); and (d) on Ag15-based cathode material at higher resolution (scale bar, 2 nm). The inset in d shows an FFT of the Ag15-based cathode material where the inner ring corresponds to (201) Li2O2 planes and the outer ring corresponds to (220) Li2O2 planes. Crystalline and amorphous regions are seen in d. The cell is discharged to 2.5 V in all cases.

The TEM image for the discharge product from the Ag9-based cathode (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 2) indicates that its building blocks are elongated nanoparticles or nanorods (~100 nm in length) that are distinctly different from the smaller and more spherical-like nanoparticles found in the discharge product of the Ag15-based cathode. The TEM image of the Ag3 discharge product in Fig. 4a reveals that it is largely made up of crystalline flat plates around 50–200 nm in size. Some nanorods are also observed in the Ag3 discharge product. Electron diffraction patterns and XRD show that the Ag3 and Ag9 discharge products contain crystalline Li2O2.

Insight into the formation mechanism in the discharge process

The dependence of the morphology of the discharge product on the size of the clusters used for the cathode can be accounted for by two mechanisms involving oxygen reduction and formation of either LiO2 or Li2O2 in the electrolyte, followed by surface nucleation and growth from the electrolyte. The mechanisms are based on assumptions derived from the characterization evidence and theoretical calculations. The assumptions include, (a) the sites for oxygen reduction and product nucleation are in different locations on the cathode surface; (b) the resulting through-solution mechanism is initiated by desorption of an oxygen superoxide radical anion from the oxygen reduction site; and (c) the electron transfer rate at the oxygen reduction site determines whether the discharge formation is from a mechanism based on surface nucleation from solution of LiO2 or Li2O2. In the following, we present evidence that supports these three assumptions and show how the resulting mechanisms account for the observed morphologies. We note that the dependence on electrolyte is not considered here since the same electrolyte was used for all clusters, but could also be a factor if electrolytes are varied.

The observed building blocks of the discharge product from the cathodes based on the three cluster sizes provide evidence for the first assumption that the formation of the discharge product occurs at a different site than oxygen reduction. Three distinct building blocks (nanorods, plates and ~spherical-like nanoparticles) are seen in the TEM images of the discharge product (Fig. 4). If formation of the building blocks occurred at the same site as oxygen reduction, the surface of the discharge product would act as the reduction site and all clusters should result in the same morphology. Thus, the formation process in the case of the Ag clusters is likely occurring by a through-solution process with the oxygen reduction species reaching the nucleation site via the electrolyte. In addition, this implies that desorption of the oxygen reduction product from the active site is necessary to make the site available for further oxygen reduction.

Density functional calculations provide evidence to support the second assumption that oxygen reduction is followed by desorption of the resulting superoxide radical anion into the electrolyte. Density functional calculations (see Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1) indicate that the O2− anion will be weakly adsorbed on an Ag15 cluster and, thus, desorption to react with a Li+ cation to form a solvated LiO2 molecule will be preferential to Li+ reaction on the surface to form an adsorbed LiO2 species. Weak binding of the O2− anion is also likely for other possible oxygen reduction sites such as the other clusters or on the cathode surface, and desorption would also occur on these cathodes. Experimental studies have shown that O2− anion is soluble in TEGDME-based electrolytes26. (Further reduction of the O2− anion or LiO2 is unlikely since it would occur at much lower discharge potential.) Following formation of the solvated LiO2 molecule, two possible solution phase mechanisms, I and II illustrated in Fig. 5, are possible based on density functional calculations of the free-energy changes. The first three steps of the two mechanisms are the same: oxygen molecule adsorption (A), electron transfer (B) and LiO2 formation (C). In mechanism I, further solvated LiO2 formation results in a supersaturated LiO2 solution (D) and nucleation and growth (E) of LiO2 at sites on the surface. In mechanism II, reaction of a second superoxide anion and a Li+ cation with a solvated LiO2 molecule (step D, Fig. 5) result in a LiO2 dimer followed by disproportionation to Li2O2 (step E) with loss of O2. This is the only through-solution mechanism for a two-electron reaction to form Li2O2 we have found on the basis of the analysis of various reactions (see Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 2). Subsequently, Li2O2, after reaching a supersaturated solution (step F), will nucleate and grow on surface sites (step G). There have been other proposed through-solution formation mechanisms6,35,36,37, although these have generally assumed that crystal growth occurs in solution. However, homogeneous nucleation and growth occurring in solution is hard to rationalize because of the different observed building blocks under the same conditions. Likewise, the different building blocks also make it hard to rationalize surface growth of lithium peroxide without solution phase transport of the reduced species for the Ag cluster-based cathodes.

Illustration of two discharge reaction mechanisms based on an initial oxygen reduction at an active site followed by solution phase reactions and growth at a surface nucleation site. (a) Mechanism I: step A: electron transfer to O2; step B: O2− desorption; step C: Li+ reaction with O2− to form solvated LiO2; step D: repetition of steps A–C for LiO2 formation to reach supersaturated LiO2 solution; step E: surface nucleation and growth of LiO2 that undergoes disproportionation. (b) Mechanism II: step A: electron transfer to O2; step B: O2− desorption; step C: Li+ reaction with O2− to form solvated LiO2; step D: addition of O2− and Li+ to form LiO2 dimer; step E: disproportionation to form Li2O2 and O2; step F: repetition of steps A–E for Li2O2 formation to reach supersaturated Li2O2 solution; step G: surface nucleation and growth of Li2O2.

Finally, we address the assumption that electron transfer rate at the oxygen reduction site determines whether the formation mechanism proceeds through mechanism I or II for the cathodes based on Ag clusters. A slow electron transfer rate will cause a slow (solvated) LiO2 molecule formation rate. This will enable the LiO2 dimer disproportionation in mechanism II since the half-life of the dimer has very short lifetime38, and will, thus, lead to heterogeneous nucleation of Li2O2 on the cathode surface from a supersaturated solution. Since the building blocks of discharge products based on Ag3 (plates) and Ag9 (nanorods) are consistent with possible Li2O2 nanoparticle shapes39,40 they will result from mechanism II. On the other hand, a fast electron transfer rate will favour formation of solvated LiO2 molecules over dimer disproportionation in solution and result in LiO2 heterogeneous nucleation as in mechanism I. Since the spherical-like nanoparticle building blocks of the cathode based on Ag15 clusters are unlike the other building blocks or what is expected for Li2O2, they will result from mechanism I. The spherical particles may also be responsible for the smoother layered-like appearance found in the SEM images (Fig. 3c). Mechanism I involves disproportionation of the solid LiO2 discharge product on the cathode surface, which appears to contain crystallites, presumably Li2O2 and amorphous regions (grain boundaries) of either Li2O2 and/or remaining LiO2 (Fig. 4c,d). The resulting building blocks from the different mechanisms then undergo assembly into mesoscale aggregates that compose the discharge product. The explanation for the toroidal shape of the aggregates is beyond the scope of our model, but a mathematical model41 has been presented by others on nucleation and conformal growth of Li2O2 crystals.

Density functional calculations of the initial nucleation structures of Li2O2 on alumina-supported Ag3 and Ag9 clusters provide an explanation of the differing building blocks resulting from cathodes based on these two cluster sizes. The results in Fig. 6 indicate that for an Ag3 cluster, flat (Li2O2)n structures (Fig. 6b) are energetically more favourable (0.49 eV per Li2O2 unit) than upright structures (Fig. 6a). This could account for the film-like structure with crystalline plates, which is observed for the discharge product on the Ag3-based cathode from the TEM results (Fig. 4a). Similar density functional calculations were carried out on alumina-supported Ag9 clusters. In this case the calculations show that the upright (Fig. 6c) and flat (Li2O2)n clusters are much closer in energy (see Supplementary Fig. 5). This suggests that the three-dimensional Ag9 cluster could be a nucleation site for the observed elongated nanorod-type Li2O2 nanoparticles found in the TEM images (Fig. 4b). We note that, if the clusters act as nucleation sites, the largest toroid size should occur for the cluster size with the lowest cluster density on the surface due to the smaller number of nucleation sites. This is consistent with the largest toroids being found for Ag15 clusters (1,000 nm), see Fig. 3, and with smaller toroids (500 nm) for Ag9 clusters.

(a) Lithium peroxide nanorod on an Ag3 cluster; (b) lithium peroxide film on an Ag3 cluster, which is favoured by 0.49 eV per Li2O2 unit compared with the nanorod on an Ag3 cluster; (c) lithium peroxide nanorod on an Ag9 cluster. Colour code: silver=Ag, blue=Al, red=O and yellow=Li. See Supplementary Fig. 6 for more details on all calculations. (d–f) Density of states for Ag3, Ag9 and Ag15 clusters on an amorphous hydroxylated alumina surface.

Density functional calculations of the electronic structures of the three clusters on a hydroxylated alumina surface also provide a possible explanation for different oxygen reduction rates of the cathodes. The results indicate that both supported Ag3 and Ag9 clusters have a gap at the Fermi level (Fig. 6d,e), while Ag15 shows no gap at the Fermi level (Fig. 6f). The large difference in density of states suggests that the Ag15 site will have more favourable electron transfer than Ag3 or Ag9 resulting in the faster LiO2 formation needed for mechanism I. Since the Ag3 and Ag9 charge profiles and capacities are similar to those of the alumina-coated carbon cathode without clusters, the oxygen reduction sites are not likely the clusters in these cases, but rather other cathode surface sites. We also note that the high charge potentials (4 V) for the discharge products from the Ag3- and Ag9-based cathodes (Fig. 2) are consistent with morphologies having poor electronic transport due to larger building blocks (Fig. 4) and lack of a grain boundary network. In contrast, the lower charge potential (~0.7 V lower) observed for the Ag15-based cathode is consistent with its smaller nanoparticles and amorphous (grain boundary) network. Such a network could have good electronic conductivity as density functional theory (DFT) calculations15 have shown that amorphous Li2O2 has no band gap. Results for an Ag18-based cathode (see Supplementary Fig. 7) are also consistent with the observed cluster size dependence as the Ag18 cluster has a larger band gap and gives results similar (that is, nanorods and large charge potential) to the Ag9-based cathode.

Discussion

In summary, this study of the Li–O2 discharge product morphology based on precisely controlled size-selective subnanometre transition metal clusters added to the cathode has revealed a dramatic dependence on cluster size. Such surprising subnanometre size effects have been found recently for other types of electrocatalytic reactions23,42 as well as heterogeneous catalytic reactions20,21,22. However, this is the first time that size-selected subnanometre clusters have been studied in Li–O2 cells. The different morphologies of the Li–O2 discharge products provide evidence, supported by DFT calculations, for discharge mechanisms involving oxygen reduction and formation of either LiO2 or Li2O2 in the electrolyte, followed by surface nucleation and growth from the electrolyte. The dependence of the discharge mechanisms on oxygen reduction rate can account for the differing discharge product morphologies with different charge overpotentials. This study of specific and well-defined clusters on cathode surfaces provides evidence that subnanometre surface species can strongly influence the morphology of the discharge products in Li–O2 cells. These results imply that characterization of the subnanometre surface structure of cathodes is a key factor in understanding the discharge and charge chemistries in lithium–air cells and the tailoring of this structure is a potential avenue to reduce the charge overpotentials, increase capacities, and possibly increase cycle life with less reactive surface morphologies. It will be of interest to investigate other subnanometre transition metal clusters in Li–O2 to determine how they control the discharge and charge chemistries.

Methods

Cathode preparation

GC black with a typical particle size 40 nm and a surface area 62 m2 g−1 was used as the catalyst support material. ALD was performed in a continuous-flow stainless steel reactor described in detail elsewhere. About 100 mg of the GC powder was carefully spread onto a stainless steel tray, and a stainless steel mesh cover was clamped over the tray to contain the powder while still providing access to the ALD precursor vapours. The carbon powder was held in the reactor at 200 °C under continuous flow of 300 s.c.c.m. ultra-high-purity nitrogen carrier gas at 1 torr pressure for 30 min to outgas, and achieved thermal equilibrium. The Al2O3 ALD used alternating exposures to trimethyl aluminium (TMA, Sigma-Aldrich, 97%) and deionized water at 200 °C. Exposure/purge time 60s-120s-60s-180s was used. The three-cycle Al2O3 ALD on the carbon black powder was performed to cover the carbon defect sites. The pristine cathode laminate was formed by casting a mixture of the as-prepared Al2O3-coated Super P Li (SPL) carbon and binder in a molar ratio of 80:20. Size-selected Agn (n=3, 9, 15, 18) clusters were soft landed on the alumina-coated SPL carbon laminates under identical deposition and coverage conditions (corresponding to 12.35% ML of an ideal smooth surface). In this study, the molecular beam of silver clusters was produced by magnetron sputtering of a silver target using a mixture of argon and helium as the sputtering gas and helium as carrier gas. Next, the charged particles contained in the beam were focused using a conical octupole, passed through a linear octupole ion guide and mass selected by a quadrupole mass filter before the positively charged cluster ions were soft landed on the support. The charge of gas–phase positively charged clusters was neutralized by the current from a picoammeter that is used to bias the support during landing and to monitor the flux of charge in real time on interaction with the conductive support creating a current that is monitored in real time using a picoammeter to determine the coverage flux of particles reaching the support. The amount of deposited metal was determined by integrating the deposition flux over time (that is, total charge of clusters measured at the surface) and the number of atoms in the cluster.

Electrochemical methods

Electrochemical characterization was carried out using a Swagelok-type cell composed of a lithium metal anode, electrolyte (1 M LiCF3SO3 in TEGDME impregnated into a glass fibre separator) and a porous cathode (13 mm diameter). The cells were sealed except for the Al grid window that exposed the porous cathode to 1 bar O2 pressure. The electrochemical measurements were carried out using a Maccor cycler. The discharge–charge performance was conducted at a constant current of 100 mA g−1 (carbon), and the cell was maintained in 1 bar O2 atmosphere to avoid any negative effects of humidity and CO2. For comparison, a blank Al2O3-coated SPL carbon without any catalyst was also tested using the same cell configuration described above. We normalized the observed capacity by the weight of the carbon for comparison in this study.

High-energy XRD

The cathode laminates after discharge were characterized by high-energy synchrotron XRD to determine the formation of Li2O2, which was carried out at the 11-ID-C beamline of the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. The X-ray wavelength was 0.10804 Å. The samples were completely covered with Kapton tape as a protective film in the glove box to avoid any side reactions from the air. The XRD patterns were collected in the transmission mode using a Perkin Elmer large area detector. The collected two-dimensional patterns were then integrated into conventional one-dimensional patterns (intensity versus 2θ) for final data analysis using the Fit2d software.

Electron microscopy

A field-emission transmission electron microscope with a spherical and chromatic aberration imaging corrector working at 80 kV was employed to evaluate the morphology and particle size of the deposited Agn clusters and Li2O2 toroids. To avoid knock-out damage to carbon materials from the electron beam, 80 kV was chosen. Spherical and chromatic aberration correction enables the microscope to reach the information limit better than 0.1 nm (measured by Young’s fringes) at 80 kV. To prepare the TEM specimens, holey carbon grids are placed in the bottle of as-received powders, and shaken to allow small powders to attach on the holey carbon. No liquid was used to avoid possible morphology change due to the interaction with solution. Field-emission SEM (Hitachi S-4700) coupled with energy-dispersive spectrometry was employed to determine the morphology and estimate the particle size of Li2O2 toroids.

Theoretical methods

To study the interaction/bindings of the Ag clusters with the alumina surface and the carbon surface, we carried out DFT calculations with plane wave basis sets as implemented in VASP code. More detailed information on the DFT calculations can be found in Supplementary Methods.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Lu, J. et al. Effect of the size-selective silver clusters on lithium peroxide morphology in lithium–oxygen batteries. Nat. Commun. 5:4895 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5895 (2014).

References

Abraham, K. M. & Jiang, Z. A polymer electrolyte-based rechargeable lithium/oxygen battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 143, 1–5 (1996).

Lu, J. et al. Aprotic and Aqueous Li–O2 Batteries. Chem. Rev. 114, 5611–5640 (2014).

Lei, Y. et al. Synthesis of porous carbon supported palladium nanoparticle catalysts by atomic layer deposition: application for rechargeable lithium-O2 battery. Nano. Lett. 13, 4182–4189 (2013).

Qin, Y. et al. In situ fabrication of porous-carbon-supported α-MnO2 nanorods at room temperature: application for rechargeable Li-O2 batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 519–531 (2013).

Du, P. et al. Compatibility of lithium salts with solvent of the non-aqueous electrolyte in Li-O2 batteries. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 5572–5581 (2013).

Ottakam Thotiyl, M. M., Freunberger, S. A., Peng, Z. & Bruce, P. G. The carbon electrode in nonaqueous Li–O2 cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 494–500 (2012).

Li, Y. et al. Carbon black cathodes for lithium oxygen batteries: Influence of porosity and heteroatom-doping. Carbon 64, 170–177 (2013).

Xiao, J. et al. Hierarchically porous graphene as a lithium-air battery electrode. Nano Lett. 11, 5071–5078 (2011).

Peng, Z., Freunberger, S. A., Chen, Y. & Bruce, P. G. A reversible and higher-rate Li-O2 battery. Science 337, 563–566 (2012).

Lu, Y.-C. et al. Platinum-gold nanoparticles: a highly active bifunctional electrocatalyst for rechargeable lithium-air batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 12170–12171 (2010).

Dathar, G. K. P., Shelton, W. A. & Xu, Y. Trends in the catalytic activity of transition metals for the oxygen reduction reaction by lithium. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 891–895 (2012).

Zhang, Z. C. et al. Increased stability toward oxygen reduction products for lithium-air batteries with oligoether-functionalized silane electrolytes. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 25535–25542 (2011).

Débart, A., Paterson, A. J., Bao, J. & Bruce, P. G. α-MnO2 nanowires: a catalyst for the O2 electrode in rechargeable lithium batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 4521–4524 (2008).

Trahey, L. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and structural modeling of high-capacity, dual functioning MnO2 electrode/electrocatalysts for Li-O2 cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 3, 75–84 (2013).

Lu, J. et al. A nanostructured cathode architecture for low charge overpotential in lithium-oxygen batteries. Nat. Commun. 4, 2383 (2013).

Herzing, A. A., Kiely, C. J., Carley, A. F., Landon, P. & Hutchings, G. J. Identification of active gold nanoclusters on iron oxide supports for CO oxidation. Science 321, 1331–1335 (2008).

McCloskey, B. D. et al. On the efficacy of electrocatalysis in nonaqueous Li-O2 batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 18038–18041 (2011).

Hummelshoj, J. S., Luntz, A. C. & Norskov, J. K. Theoretical evidence for low kinetic overpotentials in Li-O2 electrochemistry. J. Chem. Phys. 138, 034703 (2013).

Viswanathan, V. et al. Electrical conductivity in Li2O2 and its role in determining capacity limitations in non-aqueous Li-O2 batteries. J. Chem. Phys. 135, 214704 (2011).

Vajda, S. et al. Subnanometre platinum clusters as highly active and selective catalysts for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Nat. Mater. 8, 213–216 (2009).

Lei, Y. et al. Increased silver activity for direct propylene epoxidation via subnanometer size effects. Science 328, 224–228 (2010).

Lee, S. et al. Selective propene epoxidation on immobilized Au6–10 clusters: the effect of hydrogen and water on activity and selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 1467–1471 (2009).

Kwon, G. et al. Size-dependent subnanometer Pd cluster (Pd4, Pd6, and Pd17) water oxidation electrocatalysis. ACS Nano 7, 5808–5817 (2013).

Freunberger, S. A. et al. Reactions in the rechargeable lithium-O2 battery with alkyl carbonate electrolytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 8040–8047 (2011).

Mizuno, F., Nakanishi, S., Kotani, Y., Yokoishi, S. & Iba, H. Rechargeable Li-air batteries with carbonate-based liquid electrolytes. Electrochem. 78, 403–405 (2010).

Black, R. et al. Screening for superoxide reactivity in Li-O2 batteries: effect on Li2O2/LiOH crystallization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2902–2905 (2012).

McCloskey, B. D. et al. Twin problems of interfacial carbonate formation in nonaqueous Li-O2 batteries. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 997–1001 (2012).

Assary, R. S. et al. The effect of oxygen crossover on the anode of a Li–O2 battery using an ether-based solvent: insights from experimental and computational studies. ChemSusChem 6, 51–55 (2013).

Nasybulin, E. et al. Effects of electrolyte salts on the performance of Li–O2 batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 2635–2645 (2013).

Assary, R. S., Lau, K. C., Amine, K., Sun, Y.-K. & Curtiss, L. A. Interactions of dimethoxy ethane with Li2O2 clusters and likely decomposition mechanisms for Li–O2 batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 8041–8049 (2013).

Yang, J. et al. Evidence for lithium superoxide-like species in the discharge product of a Li-O2 battery. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 3764–3771 (2013).

Black, R., Lee, J.-H., Adams, B., Mims, C. A. & Nazar, L. F. The role of catalysts and peroxide oxidation in lithium–oxygen batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 392–396 (2013).

Gallant, B. M. et al. Influence of Li2O2 morphology on oxygen reduction and evolution kinetics in Li-O2 batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 2518–2528 (2013).

Adams, B. D. et al. Current density dependence of peroxide formation in the Li-O2 battery and its effect on charge. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 1772–1778 (2013).

Oh, S. H., Black, R., Pomerantseva, E., Lee, J.-H. & Nazar, L. F. Synthesis of a metallic mesoporous pyrochlore as a catalyst for lithium–O2 batteries. Nat. Chem. 4, 1004–1010 (2012).

Ren, X., Zhang, S. S., Tran, D. T. & Read, J. Oxygen reduction reaction catalyst on lithium/air battery discharge performance. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 10118–10125 (2011).

Mitchell, R. R., Gallant, B. M., Shao-Horn, Y. & Thompson, C. V. Mechanisms of morphological evolution of Li2O2 particles during electrochemical growth. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 1060–1064 (2013).

Bryantsev, V. S., Blanco, M. & Faglioni, F. Stability of lithium superoxide LiO2 in the gas phase: computational study of dimerization and disproportionation reactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 114, 8165–8169 (2010).

Mo, Y., Ong, S. P. & Ceder, G. First-principles study of the oxygen evolution reaction of lithium peroxide in the lithium-air battery. Phys. Rev. B 84, 205446 (2011).

Radin, M. D., Rodriguez, J. F., Tian, F. & Siegel, D. J. Lithium peroxide surfaces are metallic, while lithium oxide surfaces are not. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 1093–1103 (2012).

Horstmann, B. et al. Rate-dependent morphology of Li2O2 growth in Li–O2 batteries. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 4217–4222 (2013).

Proch, S., Wirth, M., White, H. S. & Anderson, S. L. Strong effects of cluster size and air exposure on oxygen reduction and carbon oxidation electrocatalysis by size-selected Ptn (n≤11) on glassy carbon electrodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 3073–3086 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357 from the Vehicle Technologies Office, DOE, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) and Division of Materials Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Department of Energy, Office of Science. J.L. was supported by the DOE, Office of EERE Postdoctoral Research Award under the EERE Vehicles Technology Program administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education for the DOE. We acknowledge the financial support from the Human Resources Development of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning grant funded by the Ministry of Knowledge Economy (No. 20124010203310) of the Korean government and by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (No. 2009-0092780). We also acknowledge grants of computer time through INCITE awards for BlueGene/Q computer at Argonne National Laboratory and allocations on the CNM Carbon Cluster at Argonne National Laboratory, the ALCF Fusion Cluster at Argonne National Laboratory, and the EMSL Chinook Cluster at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Use of the Advanced Photon Source and the Electron Microscopy Center for Materials Research was supported by the US DOE, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The authors would also like to thank Dr Jeffrey W. Elam of Energy systems division at Argonne National Laboratory for his help on preparing Al2O3-coated carbon via ALD method.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and K.A. designed the experiments; E.T. and S.V. synthesized the cathode materials. J.L., D.M. and J.W. performed and analysed the imaging experiments, J.L., H.H.W. and X.L. performed and analysed the X-ray measurements, J.L., X.L., J.-B. P. and H.W. tested the cathode materials, and L.C., K.C.L., R.S.A., P.R. and L.A.C. were responsible for the theoretical computations. Y.-K.S., S.V., L.A.C., and K.A. supervised the project; L.A.C., J.L. and K.A. wrote the paper. All of the authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-7, Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 1065 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, J., Cheng, L., Lau, K. et al. Effect of the size-selective silver clusters on lithium peroxide morphology in lithium–oxygen batteries. Nat Commun 5, 4895 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5895

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5895

This article is cited by

-

Advances in heterogeneous single-cluster catalysis

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2023)

-

In situ TEM visualization of Ag catalysis in Li-O2 nanobatteries

Nano Research (2023)

-

Lithium-ion modified cellulose as a water-soluble binder for Li-O2 battery

Frontiers in Energy (2022)

-

Tuning lithium-peroxide formation and decomposition routes with single-atom catalysts for lithium–oxygen batteries

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Preparation and properties of PMMA-modified Sr2Ni0.4Co1.6O6 composites

Ionics (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.