Abstract

Small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) protein conjugation onto target proteins regulates multiple cellular functions, including defence against pathogens, stemness and senescence. SUMO1 peptides are limiting in quantity and are thus mainly conjugated to high-affinity targets. Conjugation of SUMO2/3 paralogues is primarily stress inducible and may initiate target degradation. Here we demonstrate that the expression of SUMO1/2/3 is dramatically enhanced by interferons through an miRNA-based mechanism involving the Lin28/let-7 axis, a master regulator of stemness. Normal haematopoietic progenitors indeed display much higher SUMO contents than their differentiated progeny. Critically, SUMOs contribute to the antiviral effects of interferons against HSV1 or HIV. Promyelocytic leukemia (PML) nuclear bodies are interferon-induced domains, which facilitate sumoylation of a subset of targets. Our findings thus identify an integrated interferon-responsive PML/SUMO pathway that impedes viral replication by enhancing SUMO conjugation and possibly also modifying the repertoire of targets. Interferon-enhanced post-translational modifications may be essential for senescence or stem cell self-renewal, and initiate SUMO-dependent proteolysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) proteins can be conjugated onto specific lysine residues of a wide variety of proteins, creating branched peptides1,2. Protein-conjugated SUMO binds SUMO-interacting motifs, inducing conformational changes and stabilizing intra- or intermolecular interactions3. Poly- or multi-sumoylation may also initiate polyubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation4,5. At present, sumoylation efficiency is primarily regulated by the target (presence of a canonical sumoylation site or a SUMO-interacting motif) or by E3 enzymes6,7. Most of SUMO1 is conjugated to high-affinity targets, notably to RanGap1, reflecting the fact that SUMO1 abundance is a limiting factor for conjugation. Conversely, SUMO2/3 conjugation is primarily inducible by stress8. Sumoylation is essential for life9 and regulates many biological processes, particularly stress responses10,11. We recently demonstrated a role for PML nuclear bodies (NBs), spherical structures organized by PML protein, in oxidative stress-responsive sumoylation12. There is significant evidence that SUMO conjugation opposes viral or bacterial replication and pathogens inactivate SUMO conjugation through multiple mechanisms13,14,15. Yet, the mechanisms underlying global control of SUMO expression and conjugation remain ill-understood.

Type I or II interferons (IFNs) are cytokines, activated among others by Toll-like receptors (TLRs), involved in response to virus infection, inflammation, immune signalling or stem cell control. Interestingly, multiple proteins involved in IFN signalling or downstream IFN-stimulated proteins are sumoylated16,17. Among IFN/STAT1/3 targets is the RNA binding protein Lin28B, a key developmental regulator implicated in stemness, cancer growth and metabolism18,19. Lin28 is one of the essential human genes contributing to iPSC reprogramming, and Lin28 expression is enriched in various somatic progenitors, as well as in germline and embryonic stem cells19. Mechanistically, Lin28B selectively blocks the biogenesis of let-7 family micro RNAs (miRNAs), whose downstream targets include mitogenic cytokines and oncogenes such as Ras, or Caspase 3.

Here we report that expression of SUMO paralogues is under tight control of the IFN/Lin28/let-7 axis. Such dramatic increases in SUMO abundance induced by IFN treatment or Lin28 expression should profoundly change, not only the abundance of conjugated proteins, but also the repertoire of modified proteins, particularly for SUMO1. Conjugation by SUMOs contributes to the antiviral effects of IFNs and could also be a key player in the control of differentiation and senescence.

Results

IFNs and activated TLR enhance global sumoylation

A 24-h treatment with IFNα initiated a massive increase in SUMO1 and –2/3 conjugated species in different cell lines, as well as in vivo in mice (Fig. 1a–d). The same was observed for IFNα or γ in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Fig. 1c,d). The levels of both unconjugated (arrows in Fig. 1c,d) and conjugated SUMOs sharply rose. Increase of unconjugated SUMOs after exposure to IFNα was much clearer on ectopic expression of the SUMO protease SENP1 that reverses SUMO conjugation (Fig. 1e). This implies that IFNs primarily increase the expression of SUMO peptides, and not only sumoylation efficacy. We also examined primary mouse or human monocytes stimulated with agonists of TLR, which activate IFN and nuclear factor-κB signalling. Again, IFNα or a TLR9 agonist peptide, but not a control non-TLR9 agonist, sharply enhanced global sumoylation (Fig.1f,g). Increase in SUMO conjugates was often more pronounced for high molecular weight species, which may point to the induction of SUMO chains. Collectively, IFN signalling increases SUMO levels in multiple cell types.

(a) IFNα enhances global sumoylation in HeLa cells. UBC9 and actin are shown as controls. (b) Twenty-four hours IFNα administration enhances SUMO1 and -2/3 conjugates in mice; tissues are indicated. (c) IFNα induces SUMO1- and SUMO2/3-free (arrows) and -conjugated peptides in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. (d) Similar to that in c with IFNγ. (e) HeLa cells transiently overexpressing the SUMO de-conjugating enzyme SENP1 were treated with IFNα for 24 h. IFNα enhances expression of the SUMO peptides (arrow). (f) IFNα and an agonist of TLR9 (TLR9-a) enhance the abundance of high molecular weight SUMO conjugates in primary mouse monocytes, while the inactive form of TLR9 agonist (TLR9-na) does not. PML induction demonstrates IFN production on TLR9 activation. (g) IFNα and TLR9-a enhance the abundance of high molecular weight SUMO conjugates in primary human monocytes. PML and SP100 induction demonstrates IFN production on TLR9 activation All experiments were repeated at least twice and a representative one is shown. IFNα: 1,000 IU ml−1, IFNγ: 500 IU ml−1. Note that full blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

The Lin28 and let-7 axis controls SUMO levels

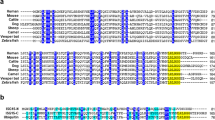

SUMO1, SUMO2 or SUMO3 mRNA expression was not increased by IFNα, suggesting the involvement of mechanism(s) other than transcriptional control (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b)20. Both IFNs and nuclear factor-κB cascades activate the STAT3/Myc/Lin28B axis, repressing expression of miRNAs from the let-7 family18,21,22,23. Indeed, in HeLa cells, 24-h IFNα treatment inhibited let-7i and let-7g expression by 80 and 60%, respectively, while miR-21 was unaffected (Fig. 2a). In mammals, miRNAs downregulate mRNA stability and protein synthesis through complementary elements in the 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) of their target mRNAs24. We identified let-7 family complementary sites (LCS) in 3′-UTRs of human SUMO1, SUMO2 and SUMO3 transcripts. SUMO1, SUMO2 and SUMO3 3-′UTRs had nine, seven and two predicted LCS, respectively (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 1c). Note that the duplexes formed between let-7 family miRNAs and SUMO 3′-UTR LCS primarily contained bulged sequences rather than perfect complementarity (Supplementary Fig. 1c), supporting a silencing mechanism relying on translational downregulation rather than mRNA degradation24. In contrast, we found no LCS on ISG15, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase or tubulin transcripts. Similar to human SUMO genes, 3′-UTRs of mouse SUMO1, 2 and 3 transcripts also contained multiple LCSs pointing to evolutionary conservation and physiological importance of this let-7-mediated silencing mechanism (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b).

(a) IFNα suppresses let-7 miRNA expression. Expression levels of mature human let-7i and let-7g were detected by quantitative PCR with and without IFNα treatment (1,000 IU ml−1). *The passenger miRNA strand of the mature miRNA duplex. miR-21 is shown as a control, P-values were calculated using two-tailed Student’s t-test. NS, not significant; means and s.d. values of two experiments. (b) LCS in 3′-UTRs of human SUMO1, SUMO2 and SUMO3 transcripts. Location of the stop codon is indicated. (c) Transfection of let-7i HIs (antagomirs) mimics IFNα-enhanced SUMO1 and 2/3 levels in HeLa cells. IFNα treatment, 24 h (1,000 IU ml−1). (d) Transfection of let-7g mimics downregulates SUMO1 and -2/3 expression and antagonizes IFNα-induced global sumoylation. IFNα treatment, 24 h (1,000 IU ml−1). (e) Down- and upregulation of SUMO1 by let-7i mimic and let-7g HI, respectively, compared with non-targeting (NT) control mimic and HI miRNAs, with Ras- and Caspase 3-positive controls. (f) 3′-UTRs of SUMO1 or SUMO2 transcripts confer IFN sensitivity to the GFP reporter. GFP fusions with the non-coding 3′-UTR of human SUMO1 or SUMO2 genes were expressed in HeLa cells treated or not with IFNα (1,000 IU ml−1) for 24 h before GFP protein quantification by western blotting. Means of three experiments, P-values (two-tailed Student’s t-test) and error bars (s.d.) are indicated. (g) 3′-UTRs of SUMO1 or SUMO2 are directly targeted by let-7. GFP fusions with the non-coding 3′-UTR of human SUMO1 or SUMO2 genes were co-expressed with let-7i antagomirs (HI) in HeLa cells. Means of two experiments, error bars (s.d.) are indicated. NT HI: non-targeting control antagomir.

Inhibition of endogenous let-7i and let-7g expression by specific let-7 antagomirs (HI, hairpin inhibitor), but not by a non-targeting control antagomir, led to global upregulation of sumoylation, mimicking the effects of IFNα (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2c) and demonstrating a basal repressive activity of these miRNAs on SUMO expression. Conversely, ectopic overexpression of let-7i and let-7g decreased basal or IFNα-enhanced sumoylation (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2c). As expected, expression of other known let-7 targets such as Ras or Caspase 3 were upregulated by let-7 antagomirs or suppressed by let-7 mimics, respectively (Fig. 2e). Essentially similar results were obtained when analysing SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 (Fig. 2c,d). Furthermore, fusion of a complementary DNA encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) to the non-coding 3′-end of the SUMO1 or SUMO2 genes confirmed the role of the SUMO 3′-UTR in conferring IFNα sensitivity (Fig. 2f), as well as direct let-7 targeting (Fig. 2g). Thus, IFN-enhanced sumoylation involves let-7.

Decrease of SUMO abundance by Lin28 loss or differentiation

Lin28 may indirectly enhance SUMO expression by antagonizing let-7 expression. Indeed, directly inactivating Lin28 expression by small interfering RNA (siRNA) led to a sharp decrease in both unconjugated and conjugated SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 (Fig. 3a). Thus, the Lin28/let-7 axis controls basal and IFN-enhanced SUMO1/2/3 expression.

(a) Conjugated (left) and unconjugated (right) SUMOs expression is decreased on Lin28A and B silencing by siRNAs. All experiments were repeated at least twice and a representative one is shown. (b) Expression of SUMO1/2/3 is increased in haematopoietic progenitors compared with total bone marrow. Lineage negative (Lin−) progenitor cells representing <10% of the total bone marrow were analysed by western blotting. Arrows point to unconjugated SUMOs. Representative experiment of two independent ones. (c) Concomitant with Lin28 decline, SUMO conjugates are decreased in NB4 cells differentiated after ATRA exposure for 48 h.

Lin28 proteins have recently emerged as key factors defining stemness in various lineages25,26,27, questioning the existence of a gradient of SUMO expression during normal differentiation. To address this issue, we isolated mouse haematopoietic progenitors and compared their sumoylation profile with that of total marrow primarily containing their differentiated progeny. In haematopoietic progenitors, as defined by the absence of expression of any lineage markers (Lin−), we observed a dramatic enrichment of unconjugated SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 3a). SUMO1, but not SUMO2/3, conjugates were also clearly upregulated, suggesting that in these primary cells, SUMO2/3 may require a stress signal to undergo conjugation.

Lin28 upregulation was also implicated in cellular transformation. For example, Lin28 levels decrease rapidly during all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA)-induced differentiation of mouse embryonic carcinoma cells28, and during ATRA-induced differentiation of human promyelocytic leukemia NB4 cells, let-7 miRNA levels increase29. As predicted, NB4 differentiation led to a dramatic decrease in Lin28B levels and a sharp decline in SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 conjugates (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3b). Collectively, these results demonstrate that decreased Lin28 levels correlate with impaired sumoylation, possibly contributing to Lin28-mediated regulation of stemness and differentiation.

IFN-induced SUMOs are required for IFN antiviral effects

SUMOs oppose the replication of viruses or bacteria, raising the possibility that they mediate, at least in part, the effects of IFN on pathogens13,14. Several viral or bacterial proteins downregulate global sumoylation. For example, the Herpes virus ICP0 protein targets sumoylated proteins to the proteasome30 (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, only ICP0-defective HSV1 is susceptible to IFNα31 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig 4a). To formally demonstrate the role of IFNα-induced SUMOs in the antiviral effects of this cytokine, we compared viral replication in U2OS cells transfected with siRNAs against SUMO1/2/3 and then treated or not with IFNα, before infection with wild-type or ICP0-defective HSV1. Downregulation of SUMOs favoured (<3-fold) HSV1 replication, confirming their role as antiviral peptides (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). However, a striking effect of SUMO downregulation was observed on IFNα-treated cells. Although IFN inhibited replication of the ICP0-defective mutant virus (by 59-fold, Fig. 4b), this antiviral effect was blunted on silencing of SUMOs (12-fold reduction). Thus, SUMOs are critical downstream mediators of IFN antiviral effect.

(a) Downregulation of IFNα-induced sumoylation by ICP0 protein of HSV. HeLa cells overexpressing ICP0 were treated with IFNα (1,000 IU ml−1) for 24 h. Vinculin is shown as a loading control. (b) SUMOs and PML are required for IFNα antiviral effect. U2OS cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, treated with IFNα (1,000 IU ml−1) for 24 h, and infected with wild-type or ICP0-deficient HSV1 for another 24 h. Virus was titrated from the lysates by plaque assays. Histograms are represented using logarithmic scale; mean±s.d. of four independent experiments. P-values (two-tailed Student’s t-test) and error bars (s.d.) are indicated. NT, not treated. (c) SUMOs are critical for IFNα antiviral effects against HIV (left) and murine leukemia virus (B-MLV, right). HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, treated with IFNα (1,000 IU ml−1) for 24 h and infected with glycoprotein G of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSVg)-pseudotyped HIV or murine leukemia virus viral particles containing a genomic transfer vector encoding GFP. Infectivity was scored by measuring the percentage of cells expressing GFP 24 h post infection by cell sorting. IFNα-induced fold-decrease in infectivity is shown for each condition (means of three experiments) along with P-values (two-tailed Student’s t-test) indicating significant differences and error bars (s.d.) are shown. (d) Schematic representation integrating SUMO regulation by the IFN/Lin28/let-7 pathway and PML NB-faciliated sumoylation (E3-like activity) in the control of downstream functions.

IFN-inducible PML protein has intrinsic antiviral activity32,33 and promotes sumoylation of specific substrates recruited on PML NBs12. This suggested that PML might redirect IFN-induced SUMOs towards PML NB partners, such as SP100, rather than non-NB-partner proteins such as RanGAP1. Indeed, in the absence of PML, RanGAP1 sumoylation was considerably more enhanced by IFN (Supplementary Fig. 4c), while efficient IFN-induced SP100 sumoylation is known to require PML12. IFN antiviral effect against HSV1 was impeded by PML silencing (11-fold reduction, Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4b), in keeping with previous reports31,34. Importantly, PML and SUMO inactivation did not synergize, strongly suggesting that they act on the same pathway. Thus, SUMOs and PML cooperate to enforce hypersumoylation of targets that are essential for IFNα-initiated anti-HSV1 effects.

We finally investigated the role of SUMO induction on the replication of two retroviruses, HIV and B-Murine Leukemia Virus. Again, IFNα suppressed infectivity of both viruses by approximately fourfold, an effect which was significantly impeded (>50%) on inactivation of SUMOs (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 4d). Thus, IFN-triggered hypersumoylation directly contributes to the protection against a variety of viruses.

Discussion

In general, post-translational modifications are primarily regulated by interactions between protein targets and their modifying enzymes, rather than by the availability of the molecule to be conjugated. Here we unravel major changes in the abundance of SUMOs in IFNα/γ response, and link them to Lin28/let-7 cascade (Fig. 4d). Another less-studied IFN-responsive ubiquitin-like peptide, ISG15, was recently implicated in control of mycobacterial infection35,36,37. Thus, apart from target gene induction by STATs and IRFs, which play non-overlapping roles in antiviral activities38, activation of ubiquitin-like post-translational modification may be key, global and previously underappreciated, effectors underlying IFN responses.

In normal cells, SUMO1 is limiting and almost entirely conjugated to RanGAP1 (ref. 1). On IFN treatment or in progenitors, unconjugated SUMO1 becomes abundant (Figs 1c–f and 3b), making it available for the conjugation of low-affinity targets. Thus, our observations predict a profound change in the repertoire of SUMO1-conjugated proteins on IFN exposure. PML, another IFN-induced protein39, promotes sumoylation by favouring interactions between UBC9, the universal SUMO E2 ligase and specific partners within PML NBs12. Several of these partners are themselves transcriptionally controlled by IFN, notably SP100 (ref. 40). Often in their sumoylated forms, some partners have been implicated in IFN effects on senescence (DAXX, p53, SP100) or antiviral defence (SP100)41,42,43,44,45,46. These unexpected findings therefore point to the existence of a highly integrated regulatory loop wherein the substrates, their modifiers (SUMOs) and the catalyser (PML NBs) are all dramatically upregulated during IFN response, promoting the rapid formation of the active, SUMO-conjugated form. This integrated IFN-driven pathway is targeted by multiple viral or bacterial proteins, which abrogate de novo sumoylation, promote desumoylation, degrade SUMO conjugates or de-organize PML NBs15,47.

The evolutionary conservation of the miRNA-based regulation points to the importance of the regulatory loop identified here. Apart from virus infection, there is circumstantial evidence that IFN control over SUMO or PML abundance may be also important for other processes. Early progenitors are very SUMO rich, consistent with studies that have linked SUMOs to stem cell maintenance48,49,50. PML was also implicated in regulation of stem cell fate51, notably through TR2 sumoylation, which directly controls expression of Oct-4 (refs 52, 53), or through p53 activation54. Thus, IFN-initiated, PML-enforced hypersumoylation may control stem cell self-renewal and/or proliferation42,55. Lin28 controls metabolism19,56, as recently shown for PML57,58. Future studies should clarify any implication of SUMOs in these processes. Finally, PML or SUMOs were repeatedly associated with the control of IFN signalling through STAT1 or IRF3/7 conjugation16,17,59,60, suggesting the existence of a feed-back loop.

As hypersumoylation can promote polyubiquitination4, our findings also have important implications for regulation of proteolysis. IFNs induce a transient global polyubiquitination61, which could result from the hypersumoylation unravelled here. These findings have important therapeutic relevance, as IFNα promotes PML- and SUMO-dependent degradation of toxic proteins in the brain62,63 or of the HTLV-I leukemia oncoprotein Tax64, with unambiguous clinical benefit62,65,66. Thus, similar to therapies based on manipulation of ubiquitin-dependent degradation67,68, this could pave the way to IFN-triggered, SUMO-based therapies promoting the proteolytic clearance of undesirable proteins68.

Methods

Bioinformatics and modulation of microRNA expression

Binding sites for let-7 miRNA family members on human and mouse SUMO1, 2 and 3 transcripts and predicted duplex formations were determined using miRanda application69. miRIDIAN mimic hsa-let-7g or hsa-let-7i, miRIDIAN HI hsa-let-7g or hsa-let-7i or scrambled control oligos were from Dharmacon. Expression levels of mature let-7g, let-7i and miR-21 were determined by quantitative PCR using miRCURY LNA universal cDNA synthesis kit, miRCURY LNA SYBR® Green master mix and hsa-let-7g-, hsa-let-7i-, hsa-let-7g*-, hsa-let-7i*- and hsa-miR-21-specific primers (Exiqon). U6 small nuclear RNA was used as an internal control. Expression levels of murine SUMO1, SUMO2, SUMO3 and PML transcripts were determined by quantitative PCR using Taqman probe-based gene expression analysis (Applied Biosystems), where a glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase probe was used as an internal control.

Constructs

Expression vector for Senp1 was a gift from E.Y. Yeh and expression vector for ICP0 from B. Roizman. 3′-UTRs of SUMO1 and SUMO2 genes were amplified by PCR from HeLa genomic DNA (SUMO1 3′-UTR forward: 5′-TTT ATT TCT AGA AAT AGT TCT TTT GTA ATG TGG-3′, SUMO1 3′-UTR reverse: 5′-CAT GCC TCT AGA TTC AAC ATG ATT AGG TAA CTG-3′; SUMO2 3′-UTR forward: 5′-GGT GTC TCT AGA AAA GGG AAC CTG CTT CTT TAC-3′, SUMO2 3′-UTR reverse: 5′-ACT ACT TCT AGA TCA TTT TAA ACA AGA AGT TTA TTT AAA C-3′) and inserted into the XbaI site of pEGFP-N1 (Clontech). As IFN downregulates expression from the cytomegalovirus promoter, expression levels of SUMO 3′-UTR–GFP fusions were normalized to the unfused GFP control. Basal expression levels of GFP fusions are lower than that of the unfused GFP control in accordance with basal cellular suppressive effects of endogenous let-7 miRNAs. For simplicity, basal expression levels of all GFP constructs (fused or unfused) were normalized to 1 in Fig. 2f,g.

Antibodies

Mouse monoclonal anti-SUMO1 (21C7) and rabbit polyclonal anti-SUMO2/3 antibodies were from Invitrogen. All primary antibodies were used for western blot analysis at 1/1,000 in TBS-0.1% Tween 20. Mouse monoclonal anti-GFP antibody was purchased from Roche (clones 7.1 and 13.1) and rabbit polyclonal anti-Lin28B antibodies were from Cell Signaling (4196S) and Abcam (ab71415). Goat polyclonal anti-human Caspase 3 (L-18) and mouse monoclonal anti-vinculin (7F9) antibodies were from Santa Cruz, rabbit polyclonal anti-human N-Ras (N5385-01D) antibody was from US Biological. Chicken anti-human PML and rabbit polyclonal anti-SP100 antibodies are homemade antibodies. Mouse monoclonal anti-mouse PML was kindly provided by Scott W. Lowe. All antibodies were revealed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:20,000, from Jackson). SUMO conjugates were separated on pre-casted 4–12% gradient gels (Invitrogen).

Cell culture and treatments

HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FCS. siRNAs against Lin28A and B were from Qiagen (Hs Lin28_5, Hs Lin28_6, Hs Lin28B_1 and Hs Lin28B_2). siRNAs against SUMO1, 2 or 3 were from Qiagen4. Let-7 HI or mimics were transfected using DharmaFECT-1 Transfection Reagent (Dharmacon) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, at 25 nM where not indicated. Cells were lysed 72 h post transfection for protein analysis. IFNα or γ (human IFNα, Roche; mouse IFNα and γ, Hycult Biotech) were used at 1,000 and 500 IU ml−1, respectively, for the indicated period of time. ATRA exposure on NB4 cells, cultured at 2 × 105 ml−1 in RPMI 10% fetal bovine serum, was performed at 10−6 M for 48 h. Differentiation of cells was analysed by MGG (May–Grünwald Giemsa) staining. Lin− cells were obtained from fresh mouse bone marrow by depletion using rat anti-mouse CD4, CD8, MacI, GrI, B220 antibody cocktail on anti-rat IgG Dynabeads (Life Technologies). FACS on bone marrow and lin− cells was then performed with the same cocktail to ensure enrichment. Primary mouse monocytes were isolated on depletion of other lineages from blood using anti-B220 (CD45R), anti-GR1 (Ly6G, Ly6C), anti-CD5 (Ly1) and anti-CD8a (Ly2) antibodies (Miltenyi Biotech), and kept in culture in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FCS, interleukin-3, interleukin-6 and Stem Cell Factor for 24 h. Primary human monocytes were isolated from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells using the Monocyte Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotech), and the purity of enriched monocytes was evaluated by flow cytometry, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Human and mouse TLR9 agonists (ODN2216 and ODN1585) and the non-agonist controls were from InvivoGen and used at 5 × 10−6 M final concentration for 24 h.

In vivo treatments

Mouse handling was performed in accordance with established institutional guidance and approved protocols from the Comité Régional d’Ethique Expérimentation Animale n°4, which enforces the EU 86/609 directive. Female FVB-Nico mice of 8 weeks were treated with 106 IU murine IFNα for 1 day, after which they were killed by cervical dislocation, organs were collected and protein extracts analysed by western blotting.

Viral infections and statistical analyses

Wild-type and ICP0-deleted R7910 HSV1 were obtained from B. Roizman (University of Chicago). U2OS cells, which were chosen for efficient replication of ICP0-defective virus31, were cultured in standard medium, transfected twice with siRNA against SUMO1/2/3, PML or control siRNA, and treated then with IFNα (1,000 IU ml−1) for 24 h before infection. One day post infection, cells were lysed and virus titres determined by plaque assays. Comparison of virus titres was performed using two-tailed Student’s t-test, assuming unequal variances.

HIV and B-murine leukemia virus viral stocks were produced by transfection of 293T cells using a standard calcium–phosphate precipitation technique. Briefly, cells were transfected with plasmids encoding the HIV or MLV packaging DNA, the genomic transfer vector encoding GFPor RFP (red fluorescent protein) and an expression vector for the glycoprotein G of vesicular stomatitis virus. Supernatants were collected 40 h post transfection, clarified by low-speed centrifugation and filtered through 0.45-μm pore size filters. HIV viral particles were concentrated by ultracentrifugation (24,000 r.p.m., 90 min, 4 °C) using a SW32 rotor (Beckman) on a 20% sucrose cushion. All viral stocks were titrated by infection of 293T cells. After 48 h, the percentage of GFP- or RFP-expressing cells was measured by flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). HeLa cells (20,000 cells per well in 24-well plates) were then transfected with siRNA against SUMO1/2/3 or control non-targeting siRNA and treated with IFNα (1,000 IU ml−1) for 24 h before infection with glycoprotein G of vesicular stomatitis virus-pseudotyped HIV or MLV viral particles. Infectivity was scored by measuring the percentage of cells expressing the GFP or RFP reporter gene by flow cytometry 24 h post infection.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Sahin, U. et al. Interferon controls SUMO availability via the Lin28 and let-7 axis to impede virus replication. Nat. Commun. 5:4187 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5187 (2014).

References

Yeh, E. T. SUMOylation and De-SUMOylation: wrestling with life’s processes. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 8223–8227 (2009).

Cubenas-Potts, C. & Matunis, M. J. SUMO: a multifaceted modifier of chromatin structure and function. Dev. Cell 24, 1–12 (2013).

Gareau, J. R. & Lima, C. D. The SUMO pathway: emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation and recognition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 861–871 (2010).

Lallemand-Breitenbach, V. et al. Arsenic degrades PML or PML-RARalpha through a SUMO-triggered RNF4/ubiquitin-mediated pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 547–555 (2008).

Tatham, M. H. et al. RNF4 is a poly-SUMO-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase required for arsenic-induced PML degradation. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 538–546 (2008).

Geiss-Friedlander, R. & Melchior, F. Concepts in sumoylation: a decade on. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 947–956 (2007).

Meulmeester, E., Kunze, M., Hsiao, H. H., Urlaub, H. & Melchior, F. Mechanism and consequences for paralog-specific sumoylation of ubiquitin-specific protease 25. Mol. Cell 30, 610–619 (2008).

Saitoh, H. & Hinchey, J. Functional heterogeneity of small ubiquitin-related protein modifiers SUMO-1 versus SUMO-2/3. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 6252–6258 (2000).

Nacerddine, K. et al. The SUMO pathway is essential for nuclear integrity and chromosome segregation in mice. Dev. Cell 9, 769–779 (2005).

Dellaire, G. & Bazett-Jones, D. P. PML nuclear bodies: dynamic sensors of DNA damage and cellular stress. Bioessays 26, 963–977 (2004).

Lallemand-Breitenbach, V. & de The, H. PML nuclear bodies. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000661 (2010).

Sahin, U. et al. Oxidative stress-induced assembly of PML nuclear bodies controls sumoylation of partner proteins. J. Cell Biol. 204, 931–945 (2014).

Everett, R. D., Boutell, C. & Hale, B. G. Interplay between viruses and host sumoylation pathways. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 400–411 (2013).

Ribet, D. & Cossart, P. Pathogen-mediated posttranslational modifications: A reemerging field. Cell 143, 694–702 (2010).

Ribet, D. et al. Listeria monocytogenes impairs SUMOylation for efficient infection. Nature 464, 1192–1195 (2010).

Begitt, A., Droescher, M., Knobeloch, K. P. & Vinkemeier, U. SUMO conjugation of STAT1 protects cells from hyper-responsiveness to interferon-{gamma}. Blood 118, 1002–1007 (2011).

Ungureanu, D., Vanhatupa, S., Gronholm, J., Palvimo, J. J. & Silvennoinen, O. SUMO-1 conjugation selectively modulates STAT1-mediated gene responses. Blood 106, 224226 (2005).

Leppert, U., Henke, W., Huang, X., Muller, J. M. & Dubiel, W. Post-transcriptional fine-tuning of COP9 signalosome subunit biosynthesis is regulated by the c-Myc/Lin28B/let7 pathway. J. Mol. Biol. 409, 710–721 (2011).

Shyh-Chang, N. & Daley, G. Q. Lin28: primal regulator of growth and metabolism in stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 12, 395–406 (2013).

Der, S. D., Zhou, A., Williams, B. R. & Silverman, R. H. Identification of genes differentially regulated by interferon alpha, beta, or gamma using oligonucleotide arrays. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 15623–15628 (1998).

Mendell, J. T. & Olson, E. N. MicroRNAs in stress signaling and human disease. Cell 148, 1172–1187 (2012).

Guo, L. et al. Stat3-coordinated Lin-28-let-7-HMGA2 and miR-200-ZEB1 circuits initiate and maintain oncostatin M-driven epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene 32, 5272–5282 (2013).

Ohno, M. et al. The modulation of microRNAs by type I IFN through the activation of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 in human glioma. Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 2022–2030 (2009).

Su, H., Trombly, M. I., Chen, J. & Wang, X. Essential and overlapping functions for mammalian Argonautes in microRNA silencing. Genes Dev. 23, 304–317 (2009).

Richards, M., Tan, S. P., Tan, J. H., Chan, W. K. & Bongso, A. The transcriptome profile of human embryonic stem cells as defined by SAGE. Stem Cells 22, 51–64 (2004).

Viswanathan, S. R., Daley, G. Q. & Gregory, R. I. Selective blockade of microRNA processing by Lin28. Science 320, 97–100 (2008).

Yu, J. et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318, 1917–1920 (2007).

Wu, L. & Belasco, J. G. Micro-RNA regulation of the mammalian lin-28 gene during neuronal differentiation of embryonal carcinoma cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 9198–9208 (2005).

Pelosi, A. et al. miRNA let-7c promotes granulocytic differentiation in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncogene 32, 3648–3654 (2012).

Boutell, C., Sadis, S. & Everett, R. D. Herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein ICP0 and is isolated RING finger domain act as ubiquitin E3 ligases in vitro. J. Virol. 76, 841–850 (2002).

Chee, A. V., Lopez, P., Pandolfi, P. P. & Roizman, B. Promyelocytic leukemia protein mediates interferon-based anti-herpes simplex virus 1 effects. J. Virol. 77, 7101–7105 (2003).

Everett, R. D., Parada, C., Gripon, P., Sirma, H. & Orr, A. Replication of ICP0-null mutant herpes simplex virus type 1 is restricted by both PML and Sp100. J. Virol. 82, 2661–2672 (2008).

Regad, T. et al. PML mediates the interferon-induced antiviral state against a complex retrovirus via its association with the viral transactivator. EMBO J. 20, 3495–3505 (2001).

Everett, R. D. et al. PML contributes to a cellular mechanism of repression of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection that is inactivated by ICP0. J. Virol. 80, 7995–8005 (2006).

Skaug, B. & Chen, Z. J. Emerging role of ISG15 in antiviral immunity. Cell 143, 187190 (2010).

Bogunovic, D. et al. Mycobacterial disease and impaired IFN-gamma immunity in humans with inherited ISG15 deficiency. Science 337, 1684–1688 (2012).

Kirkin, V. & Dikic, I. Role of ubiquitin-and Ubl-binding proteins in cell signaling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 199–205 (2007).

Schoggins, J. W. et al. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 472, 481–485 (2011).

Stadler, M. et al. Transcriptional induction of the PML growth suppressor gene by interferons is mediated through an ISRE and a GAS element. Oncogene 11, 2565–2573 (1995).

Guldner, H., Szostecki, C., Grotzinger, T. & Will, H. IFN enhance expression of Sp100, an autoantigen in primary biliary cirrhosis. J. Immunol. 149, 4067–4073 (1992).

Muromoto, R. et al. Sumoylation of Daxx regulates IFN-induced growth suppression of B lymphocytes and the hormone receptor-mediated transactivation. J. Immunol. 177, 1160–1170 (2006).

Marcos-Villar, L. et al. SUMOylation of p53 mediates interferon activities. Cell Cycle 12, 2809–2816 (2013).

Regad, T., Bellodi, C., Nicotera, P. & Salomoni, P. The tumor suppressor Pml regulates cell fate in the developing neocortex. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 132–140 (2009).

Cuchet-Lourenco, D. et al. SUMO pathway dependent recruitment of cellular repressors to herpes simplex virus type 1 genomes. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002123 (2011).

Negorev, D. G. et al. Sp100 as a potent tumor suppressor: accelerated senescence and rapid malignant transformation of human fibroblasts through modulation of an embryonic stem cell program. Cancer Res. 70, 9991–10001 (2010).

Mauri, F. et al. Modification of Drosophila p53 by SUMO modulates its transactivation and pro-apoptotic functions. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20848–20856 (2008).

Boutell, C. et al. A viral ubiquitin ligase has substrate preferential SUMO targeted ubiquitin ligase activity that counteracts intrinsic antiviral defence. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002245 (2011).

Demarque, M. D. et al. Sumoylation by Ubc9 regulates the stem cell compartment and structure and function of the intestinal epithelium in mice. Gastroenterology 140, 286–296 (2011).

Li, X., Lan, Y., Xu, J., Zhang, W. & Wen, Z. SUMO1-activating enzyme subunit 1 is essential for the survival of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in zebrafish. Development 139, 4321–4329 (2012).

Yu, L. et al. SENP1-mediated GATA1 deSUMOylation is critical for definitive erythropoiesis. J. Exp. Med. 207, 1183–1195 (2010).

Ito, K. et al. PML targeting eradicates quiescent leukaemia-initiating cells. Nature 453, 1072–1078 (2008).

Park, S. W. et al. SUMOylation of Tr2 orphan receptor involves Pml and fine-tunes Oct4 expression in stem cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 68–75 (2007).

Gupta, P. et al. Retinoic acid-stimulated sequential phosphorylation, PML recruitment, and SUMOylation of nuclear receptor TR2 to suppress Oct4 expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 11424–11429 (2008).

Ablain, J. et al. Activation of a promyelocytic leukemia-tumor protein 53 axis underlies acute promyelocytic leukemia cure. Nat. Med. 20, 167–174 (2014).

Essers, M. A. et al. IFNalpha activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature 458, 904–908 (2009).

Thornton, J. E. & Gregory, R. I. How does Lin28 let-7 control development and disease? Trends Cell Biol. 22, 474–482 (2012).

Carracedo, A. et al. A metabolic prosurvival role for PML in breast cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 3088–3100 (2012).

Ito, K. et al. A PML-PPAR-delta pathway for fatty acid oxidation regulates hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. Nat. Med. 18, 1350–1358 (2012).

Choi, Y. H., Bernardi, R., Pandolfi, P. P. & Benveniste, E. N. The promyelocytic leukemia protein functions as a negative regulator of IFN-gamma signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 18715–18720 (2006).

El Asmi, F. et al. Implication of PMLIV in Both Intrinsic and Innate Immunity. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1003975 (2014).

Seifert, U. et al. Immunoproteasomes preserve protein homeostasis upon interferon-induced oxidative stress. Cell 142, 613–624 (2010).

Chort, A. et al. Interferon beta induces clearance of mutant ataxin 7 and improves locomotion in SCA7 knock-in mice. Brain 136, 1732–1745 (2013).

Janer, A. et al. SUMOylation attenuates the aggregation propensity and cellular toxicity of the polyglutamine expanded ataxin-7. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 181–195 (2010).

El-Sabban, M. E. et al. Arsenic-interferon-alpha-triggered apoptosis in HTLV-I transformed cells is associated with tax down-regulation and reversal of NF-kappa B activation. Blood 96, 2849–2855 (2000).

El Hajj, H. et al. Therapy-induced selective loss of leukemia-initiating activity in murine adult T cell leukemia. J. Exp. Med. 207, 2785–2792 (2010).

Kchour, G. et al. Phase 2 study of the efficacy and safety of the combination of arsenic trioxide, interferon alpha, and zidovudine in newly diagnosed chronic adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL). Blood 113, 6528–6532 (2009).

Hoeller, D. & Dikic, I. Targeting the ubiquitin system in cancer therapy. Nature 458, 438–444 (2009).

Ablain, J., Nasr, R. & Bazarbachi, A. de The H. Oncoprotein proteolysis, an unexpected Achille’s Heel of cancer cells? Cancer Discov. 1, 117–127 (2011).

Enright, A. J. et al. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 5, R1 (2003).

Acknowledgements

The laboratory is supported by INSERM, CNRS, Université Paris-Diderot, Institut Universitaire de France, Ligue Contre le Cancer, Institut National du Cancer, ANR (PACRI and SLI projects), Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (Griffuel Award to HdT), Canceropôle Ile de France and the European Research Council (STEMAPL advanced grant to HdT). U.S. was supported by a fellowship of the Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale. The data were presented at the EMBO meeting ‘Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins: From structure to function’ in October 2013. We thank B. Roizman for Herpes viruses and S. Lowe for the anti-pml monoclonal antibody. We thank all members of the laboratory for help and discussions, and A. Saïb, K. Rice and A. Bazarbachi for critical review of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.L.-B. and H.dT. conceived and supervised the project; U.S., V.L.B. and H.dT. designed the experiments; U.S. and F.J. performed ex vivo IFN treatment and SUMO analyses; U.S. performed let-7 and Lin28 profiling, computational analysis and real-time PCRs; L.P. isolated primary mouse fibroblasts, monocytes and haematopoietic progenitors; X.C. isolated primary human monocytes; A.V.-P. analysed NB4 differentiation, O.F. performed in vivo IFN treatment and western blot analysis in corresponding mouse tissues; X.C. and U.S. performed HSV infections and plaque-forming assays; A.Z. and U.S. performed HIV and B-MLV infections; U.S., V.L.-B. and HdT wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-5 (PDF 910 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sahin, U., Ferhi, O., Carnec, X. et al. Interferon controls SUMO availability via the Lin28 and let-7 axis to impede virus replication. Nat Commun 5, 4187 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5187

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5187

This article is cited by

-

Exploration of nuclear body-enhanced sumoylation reveals that PML represses 2-cell features of embryonic stem cells

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Stability of HTLV-2 antisense protein is controlled by PML nuclear bodies in a SUMO-dependent manner

Oncogene (2018)

-

Viral manipulation of the cellular sumoylation machinery

Cell Communication and Signaling (2017)

-

SUMO and the robustness of cancer

Nature Reviews Cancer (2017)

-

Role of SUMO activating enzyme in cancer stem cell maintenance and self-renewal

Nature Communications (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.