Abstract

Skyrmions in magnetic materials offer attractive perspectives for future spintronic applications since they are topologically stabilized spin structures on the nanometre scale, which can be manipulated with electric current densities that are by orders of magnitude lower than those required for moving domain walls. So far, they were restricted to bulk magnets with a particular chiral crystal symmetry greatly limiting the number of available systems and the adjustability of their properties. Recently, it has been experimentally discovered that magnetic skyrmion phases can also occur in ultra-thin transition metal films at surfaces. Here we present an understanding of skyrmions in such systems based on first-principles electronic structure theory. We demonstrate that the properties of magnetic skyrmions at transition metal interfaces such as their diameter and their stability can be tuned by the structure and composition of the interface and that a description beyond a micromagnetic model is required in such systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

After the first prediction of skyrmions in magnetic materials more than 20 years ago1,2, they were intensively explored on the basis of phenomenological models3,4. Experimentally, their existence has only very recently been discussed in bulk magnetic materials5,6,7, in thin films of cubic helimagnets8,9,10 and in ultra-thin films at surfaces11,12. A skyrmion is characterized by an integer winding number or topological charge Q defined as  , where n(x,y) is the unit vector of the local magnetization and the integral is taken over the surface area. Chiral skyrmions induced by the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya (DM) interaction are stable against continuous deformations3,13,14, for example, due to external perturbations such as an applied magnetic field. Besides the fundamental interest in magnetic skyrmions due to their intriguing topological properties, they hold promise for magnetic data storage and spintronic applications14,15. Electrons traversing a topological non-trivial magnetic structure such as a skyrmion lattice acquire a Berry phase and experience a topological Hall effect16,17. Skyrmions can also be moved by an electric current due to spin-transfer torque at current densities that are five orders of magnitude smaller than those required for domain wall motion18,19. This discovery makes skyrmions potentially interesting for future applications in racetrack-like memories15 and sparked great interest in exploring current-induced skyrmion motion20,21,22,23.

, where n(x,y) is the unit vector of the local magnetization and the integral is taken over the surface area. Chiral skyrmions induced by the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya (DM) interaction are stable against continuous deformations3,13,14, for example, due to external perturbations such as an applied magnetic field. Besides the fundamental interest in magnetic skyrmions due to their intriguing topological properties, they hold promise for magnetic data storage and spintronic applications14,15. Electrons traversing a topological non-trivial magnetic structure such as a skyrmion lattice acquire a Berry phase and experience a topological Hall effect16,17. Skyrmions can also be moved by an electric current due to spin-transfer torque at current densities that are five orders of magnitude smaller than those required for domain wall motion18,19. This discovery makes skyrmions potentially interesting for future applications in racetrack-like memories15 and sparked great interest in exploring current-induced skyrmion motion20,21,22,23.

A key ingredient to the existence of magnetic skyrmion lattices is the DM interaction24,25,26, which results from spin-orbit coupling (SOC) in a structure without inversion symmetry such as a chiral crystal structure5,6,7,8,9,10 or a surface27. Recently, a nanoskyrmion lattice has been reported as the magnetic ground state in an ultra-thin magnetic Fe film on Ir(111) (ref. 11). The DM interaction induces a certain rotational sense to this spin structure leading to the formation of skyrmions, which are forced on a square lattice with a period of only 1 nm by the four-spin interaction. However, this skyrmion lattice could not be driven into a different topological state so far12 and thus this system does not seem suited to explore individual skyrmions. It was demonstrated in a recent spin-polarized scanning tunnelling microscopy experiment12 that, surprisingly, already a single additional non-magnetic layer of Pd on Fe/Ir(111) changes the magnetic properties such that a spin spiral ground state occurs and a skyrmion lattice appears only in an applied magnetic field on the order of 1 T. At slightly larger fields, individual skyrmions with a diameter of a few nanometres were created and deleted by the spin-polarized tunnelling current. However, an understanding of why this surface should exhibit a complex succession of skyrmion phases similar to those found in chiral bulk magnets while Fe/Ir(111) shows a spontaneous skyrmion lattice has been lacking.

Here we explain how the magnetic properties at such a transition metal interface are modified due to a non-magnetic overlayer based on first-principles electronic structure theory. We demonstrate the role of the interface composition and structure on the exchange interaction, the DM interaction and the magnetocrystalline anisotropy. After mapping our density functional theory calculations to an extended Heisenberg model, we use Monte Carlo (MC) and spin dynamics simulations to study the phase transitions from the spin spiral ground state to a skyrmion lattice and the ferromagnetic state in an external magnetic field. Our simulations not only confirm the succession of phases recently reported in experiments12 but also demonstrate the possibility of tailoring skyrmion properties at transition metal interfaces.

Results

First-principles calculations

We apply electronic structure theory based on density functional theory (DFT) to study the electronic and magnetic properties of transition metal interfaces (see Methods). We start with the system of a single atomic layer of Pd on a monolayer (ML) film of Fe on the Ir(111) surface. As in the experimental study11,12, we choose an fcc stacking of the Fe ML on Ir(111) and consider both fcc and hcp stacking of the Pd overlayer that was not determined experimentally. To understand the origin of the skyrmion phase, we determine the ground state and magnetic interactions for this system by performing total energy calculations for non-collinear spin structures with and without SOC28,29.

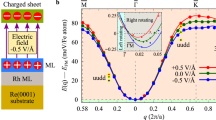

To verify the experimentally proposed ground state, we consider flat spin spirals in which the magnetic moments are confined in a plane with a constant angle between moments at adjacent lattice sites propagating along high-symmetry directions of the surface. Such a spin spiral can be characterized by a wave vector q from the two-dimensional Brillouin zone (BZ), and the magnetic moment of an atom at site Ri is given by Mi=M(sinφi, cosφi, 0) with φi=qRi and the size of the magnetic moment M (we find a value of about 2.7 μB per Fe atom in our calculations, which is fairly constant for all q vectors). The calculated energy dispersion E(q) of spin spirals for Pd/Fe/Ir(111) is displayed in Fig. 1a for an fcc stacking of the Pd overlayer. First, we consider the case neglecting SOC in our calculation. We observe that the energy dispersion along the direction  displays a shallow minimum of 1 meV in the vicinity of the ferromagnetic state (q=0), and right- (q>0) and left-rotating (q<0) spin spirals are degenerate. At larger values of |q|—that is, for increasing angle between the magnetic moments—the energy rises very quickly due to the ferromagnetic nearest-neighbour (NN) exchange interaction. A similar dispersion curve is obtained for the other high-symmetry direction as shown in the inset of Fig. 1a. A fit to the Heisenberg model reveals a strong frustration due to competing ferromagnetic exchange interactions between the NNs and antiferromagnetic exchange interactions beyond the NNs.

displays a shallow minimum of 1 meV in the vicinity of the ferromagnetic state (q=0), and right- (q>0) and left-rotating (q<0) spin spirals are degenerate. At larger values of |q|—that is, for increasing angle between the magnetic moments—the energy rises very quickly due to the ferromagnetic nearest-neighbour (NN) exchange interaction. A similar dispersion curve is obtained for the other high-symmetry direction as shown in the inset of Fig. 1a. A fit to the Heisenberg model reveals a strong frustration due to competing ferromagnetic exchange interactions between the NNs and antiferromagnetic exchange interactions beyond the NNs.

(a) Energy dispersion of homogeneous spin spirals for an atomic Pd layer in fcc stacking on Fe/Ir(111) calculated from first-principles for q vectors along the  high-symmetry direction of the two-dimensional BZ. The red and blue curves denote DFT calculations with and without SOC, respectively, and the energy is given relative to the ferromagnetic state. Note, that there is an energy shift of the spirals with respect to the ferromagnetic state of 0.35 meV on including SOC due to the magnetocrystalline anisotropy that favours an out-of-plane easy axis. The inset shows the energy dispersion along the high-symmetry direction

high-symmetry direction of the two-dimensional BZ. The red and blue curves denote DFT calculations with and without SOC, respectively, and the energy is given relative to the ferromagnetic state. Note, that there is an energy shift of the spirals with respect to the ferromagnetic state of 0.35 meV on including SOC due to the magnetocrystalline anisotropy that favours an out-of-plane easy axis. The inset shows the energy dispersion along the high-symmetry direction  . (b) Energy change on including SOC, that is, from the DM interaction (difference of red and blue curve in a). The energy is decomposed into the contributions from the Ir surface layer, the Fe ML and the Pd overlayer.

. (b) Energy change on including SOC, that is, from the DM interaction (difference of red and blue curve in a). The energy is decomposed into the contributions from the Ir surface layer, the Fe ML and the Pd overlayer.

Owing to the broken inversion symmetry at an interface, SOC induces the DM interaction24,25,26,27, which can lead to a canting of the magnetic moments of the atoms. For spin spiral states, one obtains an additional energy contribution that is linear in q close to the ferromagnetic state and due to symmetry lowers the energy only for cycloidal spirals with a unique rotational sense27 (Fig. 1b). As can be seen in Fig. 1a, an energy minimum of E≈2 meV forms, that is, right-rotating spin spirals with a pitch of λ=2π/q=3.0 nm, become more favourable than the ferromagnetic state. Note, that there is an energy shift of the spin spirals with respect to the ferromagnetic state of 0.35 meV on including SOC due to the magnetocrystalline anisotropy that favours an out-of-plane easy axis in this system. The energy contribution due to the DM interaction can be decomposed by atom types29 at the interface as shown in Fig. 1b. We find that the major contribution to the total DM term stems from the interface Ir atoms while the Pd interface plays a minor role. The magnitude of the DM interaction is similar to that found for an Fe ML on Ir(111), that is, without the Pd overlayer, which implies that the Fe/Ir interface determines the DM term.

MC simulations

To study the magnetic phase transitions in Pd/Fe/Ir(111) in an external magnetic field, we apply MC and spin dynamics simulations based on the first-principles-parameterized Hamiltonian

which describes the magnetic interactions between the magnetic moments Mi and Mj of an atom at site Ri and Rj, respectively, that is, the strength of the exchange interaction (Jij), the DM interaction (Dij) as well as an uniaxial magnetocrystalline anisotropy (K). The last term is the Zeeman energy due to the external magnetic field B applied perpendicular to the film along the z axis. All parameters in this model have been obtained for fcc and hcp stacking of the Pd overlayer from our first-principles calculations described above (see Methods for details).

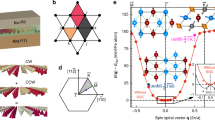

In Fig. 2a, the low-temperature phase diagram obtained from the MC simulations for fcc stacking of the Pd overlayer is displayed. At zero magnetic field, a spin spiral state with a period of about 3 nm (Fig. 2b) is energetically favourable as expected from the energy dispersion of Fig. 1a. A phase transition to a hexagonal skyrmion lattice (Fig. 2d), which gains energy with respect to the spin spiral state due to the Zeeman energy, occurs at a magnetic field of about 7 T. In this lattice the distance between adjacent skyrmions amounts to about 3.3 nm. The system undergoes a second phase transition into the saturated ferromagnetic state for magnetic fields above 17 T. At the two phase boundaries mixed states are metastable and appear on cooling down the sample in a finite magnetic field, for example, composed of spin spirals and single skyrmions (Fig. 2c) or at larger fields of isolated skyrmions in a homogeneous ferromagnetic background (Fig. 2e). By calculating the topological charge Q for spins on a discrete lattice30, we can unambiguously identify the skyrmions in these simulations (see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Qualitatively, we find the same magnetic phases as reported in the experimental study12 but at larger magnetic fields. Even quantitatively there is a reasonable agreement considering that we are using a first-principles approach without any adjustable parameters. The magnetic fields at the transitions scale with the depth of the spin spiral minimum (see Fig. 1a) and a magnetic field of 1 T corresponds to a Zeeman energy of about 0.2 meV per Fe atom.

(a) Phase diagram for fcc stacking of the Pd overlayer on the Fe ML on Ir(111) at low temperatures as a function of a magnetic field applied perpendicular to the film. The energy per Fe atom of the spin spiral (SS), the skyrmion lattice (SkX) and the saturated ferromagnetic (FM) state are given by black, red and green lines, respectively. Open circles indicate the energy of mixed states. Insets show the simulated spin-polarized scanning tunnelling microscopic images for an out-of-plane magnetized tip of the spin structures that are displayed in b–e. (b–e) A red colour denotes magnetic moments pointing up, that is, in the direction of the magnetic field, while blue spins point into the opposite direction.

For the hcp stacking of the Pd overlayer we find the same phases, that is, the spin spiral ground state, the hexagonal skyrmion lattice and the ferromagnetic state. The critical fields in this system are much smaller and on the order of the experimental values (see Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 2) while the spin spiral period and the skyrmion spacing in the lattice are about 6 nm. However, in this system, the skyrmion lattice is only metastable in our simulation. In an experiment, it may still be stabilized due to the specific sample structure, for example, by the edges of islands or by defects in the film.

A direct comparison of the spin structures obtained from our MC simulations with the experiment12 is possible by the simulation of SP-STM images31. Our first-principles calculations demonstrate that the Fe magnetic moment of about 2.7 μB leads to a considerable induced moment in the Pd overlayer of about 0.3 μB per atom. Consequently, a significant spin polarization appears in the vacuum local density of states (see Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 3), which results in a spin-polarized tunnelling current. As can be seen in the insets of Fig. 2a, there is a good agreement of the simulated images with the experimental data12 and the reported spin spiral periods between 6 and 7 nm are close to our values.

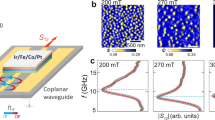

We can analyse more closely the isolated skyrmions, which can be imprinted by a spin-polarized current at elevated magnetic fields12, by taking line profiles of our MC simulations. As seen from Fig. 3a, the magnetic moments point opposite to the applied magnetic field in the skyrmion centre and rotate into the field direction in the outer region (see Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 2e). Thereby, the magnetization direction covers the entire unit sphere such that the topological charge Q amounts to one. For hcp Pd stacking, the obtained skyrmion profile at a field of 0.75 T looks very similar to that from micromagnetic simulations1,2, showing a localized skyrmion core with a diameter of about 5.4 nm and an exponential tail. (We define the skyrmion radius as in ref. 2 as the cross point of the tangent at the inflection point of the skyrmion profile with the x axis.) However, the profile of the total energy is distinctively different. We find an energy gain with respect to the ferromagnetic state close to the skyrmion centre due to the DM interaction (E<0), while at larger distances there is an energy cost due to the exchange interaction (E>0). The exchange interaction disfavours the spin rotation in the skyrmion; however, in the core this contribution is very small (Fig. 3d) due to the competition of ferromagnetic NN exchange and antiferromagnetic exchange beyond the NNs. At this magnetic field strength, the single skyrmion will cost an energy of about 36 meV.

(a) Line profile of individual skyrmions for fcc (red curve) and hcp (black curve) stacking of the Pd overlayer on Fe/Ir(111) at magnetic fields of 13 and 0.75 T, respectively. (b) Total energy difference per Fe atom with respect to the ferromagnetic reference state as a function of the distance from the skyrmion centre. (c–f) Energy difference with respect to the ferromagnetic state due to DM interaction, exchange interaction, magnetocrystalline anisotropy and the Zeeman term, respectively.

For fcc stacking of the Pd layer, we choose a magnetic field of 13 T where single skyrmions are more favourable than the ferromagnetic phase (Fig. 2a). The skyrmion diameter is reduced to about 3.5 nm in accordance with the calculated smaller spin spiral period. There is also a deviation of its profile compared with that expected from the phenomenological theory. In particular, the spins rotate a little beyond the magnetic field direction at the edge of the skyrmion (θ<0) before the rotational sense changes (dθ/dr=0) and they become fully aligned with the field. This unusual profile can be understood by analysing the energy contributions of the different magnetic interactions (Fig. 3c–f). Figure 3d shows that for fcc Pd stacking the exchange interaction favours the skyrmion over the ferromagnetic state (E<0). This is in contradiction to the predictions from the micromagnetic model that assumes a ferromagnetic exchange stiffness1,2,3,4,13,14,21,22,23,32. In Pd/Fe/Ir(111), however, we need to consider a ferromagnetic NN exchange that competes with antiferromagnetic interactions beyond the NNs. This leads to a spin spiral minimum even without SOC as seen in Fig. 1a and therefore, the exchange interaction also favours the spin rotation in the skyrmion. A single skyrmion in the ferromagnetic background thus gains an energy of about 52 meV at this field strength.

We conclude that the skyrmion profile and its stabilization by the competing magnetic interactions can depend sensitively on the specific transition metal interface. This requires a description beyond the micromagnetic model including exchange interactions beyond the NNs. From our calculations, we find that changing the structural phase of the Pd overlayer allows a variation of key parameters, such as the spin spiral pitch, the critical field strength as well as the skyrmion diameter, and its energetic stability.

Tailoring magnetic interactions at the interface

After demonstrating the occurrence of skyrmion phases in ultra-thin transition metal films, we analyse how the magnetic interactions in such a system depend on the interface structure and composition. In particular, we need to shed light on to the role of the Pd overlayer in transforming the skyrmion lattice system Fe/Ir(111) (ref. 11) into the system Pd/Fe/Ir(111) (ref. 12), which allows the observation of a succession of magnetic phases in an external magnetic field. For this purpose we compare in Fig. 4 the spin spiral energy dispersion of different film systems including SOC. We observe that for an Fe ML on Pd(111) the energy rises very quickly close to the ferromagnetic state (q=0) and the energy difference to the Néel state at the BZ boundary is about 200 meV per Fe atom, which indicates a strong ferromagnetic NN exchange interaction (J1=23.3 meV). On changing the substrate to Ir(111), the energy landscape becomes very flat up to relatively large values of q (small spin spiral periods) and eventually rises only to a small value of about 40 meV per Fe atom at the BZ boundary (J1=5.7 meV). Note that to obtain a good fit of the energy dispersions shown in Fig. 4, 5–10 exchange constants beyond NNs are required depending on the system and are used in our MC simulations. Since the SOC strength scales with the nuclear charge, that is, it is much enhanced for 5d with respect to 4d transition metals, the calculated value of the DM interaction is an order of magnitude larger for Fe/Ir(111) than for Fe/Pd(111) (D=1.7 versus −0.1 meV). Here a positive (negative) sign of D denotes a preference of spin spirals with a right-handed (left-handed) rotational sense. The large DM term in Fe/Ir(111) leads to the formation of skyrmions and due to the energy minimum at relatively large q the four-spin interaction (which favours a fast spin rotation) can enforce a square skyrmion lattice on a 1-nm length scale11.

Energy dispersion of spin spirals including SOC along the high-symmetry direction  of the two-dimensional BZ for different ultra-thin film systems: a Co ML on Pt(111), an Fe ML on Pd(111), an Fe ML on Ir(111), and one and two Pd atomic layers on an Fe ML on Ir(111). Inset shows an enlarged view of the energy dispersion close to the ferromagnetic state q=0.

of the two-dimensional BZ for different ultra-thin film systems: a Co ML on Pt(111), an Fe ML on Pd(111), an Fe ML on Ir(111), and one and two Pd atomic layers on an Fe ML on Ir(111). Inset shows an enlarged view of the energy dispersion close to the ferromagnetic state q=0.

On including a Pd overlayer on Fe/Ir(111), the energy dispersion rises again more quickly (see Fig. 4), however, with a NN exchange interaction between the two previous cases (J1=14.7 and 13.2 meV for fcc- and hcp-Pd stacking, respectively). For both stackings, it is essential to take exchange interactions beyond NNs into account to describe the energy dispersion. The DM interaction that is determined by the interface with the Ir(111) surface is of the same order and has the same sign (D=1.0 and 1.2 meV), and induces a spin spiral ground state with periods of λ=3.0 and 6.0 nm for fcc and hcp stacking, respectively. Note that, the depth of the energy minimum is much smaller for the hcp stacking that leads to smaller critical fields for the phase transitions as seen in our MC simulations. We find that an additional second Pd overlayer leads to a fine-tuning of the energy dispersion and a slightly lower value of J1=9.0 meV. Regardless, a gradual rise near q=0 is still obtained (Fig. 4) and a spin spiral energy minimum at λ=2.3 nm occurs due to the DM interaction (D=1.35 meV). We conclude that the Pd/Fe interface is crucial for tuning the exchange interactions such that a DM-driven spin spiral minimum can form. The DM interaction is mainly determined by the Ir interface and does not depend significantly on the 4d transition metal overlayer.

The modification of the exchange interaction due to the Pd overlayer seen in Fig. 4 can be understood on the basis of the hybridization of Fe 3d states with Ir 5d states and Pd 4d states. First-principles calculations show that the NN exchange interaction in a hexagonal Fe ML depends on the 4d or 5d band filling of the substrate and can be tuned from ferro- to antiferromagnetic33. On the (111) surface of Ir, which has one electron less in the d band than Pd, the NN exchange is still ferromagnetic but reduced significantly with respect to Fe/Pd(111) (J1=5.7 versus 23.3 meV). As expected from this trend, we find in our calculation that depositing a single Pd overlayer on Fe/Ir(111) leads to a rise of the NN exchange interaction, whereas for two layers of Pd on Fe/Ir(111) an intermediate value of J1 is obtained. By varying the interface composition the strength of the exchange can be tuned, which changes the spin spiral period and the depth of the energy minimum.

For comparison, we have determined the exchange and DM interaction in the related system of a Co ML on Pt(111) studied in ref. 23 as a possible candidate for current-induced skyrmion motion. We find the NN ferromagnetic exchange to be very strong (J1=27.8 meV) while the DM term is of similar magnitude as in our other systems and it favours the opposite rotational sense (D=−1.8 meV). As a result, we obtain a ferromagnetic ground state (see Fig. 4) and writing skyrmions in an ultra-thin film will cost a prohibitively large amount of energy.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have explained the occurrence of skyrmion phases in ultra-thin transition metal films at surfaces based on first-principles electronic structure theory. We have demonstrated that at transition metal interfaces with strong DM interaction it is in particular the exchange interaction that can be tuned by interface composition and structure. Thereby, a control of the skyrmion properties such as their diameter, critical fields and stability may be achieved. Our work opens the route towards predicting and tailoring skyrmion systems at transition metal interfaces and to explore their potential for future spintronic applications.

Methods

First-principles calculations

We have performed DFT calculations in the local density approximation using the film version of the full-potential linearized augmented plane wave method, which ranks among the most accurate implementations of DFT. We have used the FLEUR code ( www.flapw.de) that allows calculating the total energy of non-collinear magnetic structures such as spin spirals28 including SOC in first-order perturbation theory29. Our asymmetric films consist of one layer of Pd on one layer of Fe in fcc stacking on five layers of the Ir(111) substrate and were structurally relaxed using a mixed functional suggested in ref. 34, which is ideally suited for interfaces of 3d and 5d transition metals. The values of the relaxed interlayer distances are given in Supplementary Table 1. We have also performed calculations with thicker slabs using seven and nine layers of Ir without finding a qualitative change of the energy dispersion of spin spirals. In the MC simulations, we included exchange up to fifth NNs for hcp-Pd stacking and up to tenth NNs for fcc-Pd stacking on Fe/Ir(111). For the DM interaction, the NN approximation was found to be sufficient to fit the results from the DFT. To obtain the magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy (MAE), films with up to 15 Ir layers have been used. We find that Pd/Fe/Ir(111) possesses an easy out-of-plane axis with a MAE of 0.7 and 0.8 meV per Fe atom for fcc- and hcp-stacking of the Pd overlayer, respectively. For two layers of Pd (in fcc stacking) on Fe/Ir(111) we obtain a MAE of 0.8 meV per Fe atom. The convergence with the number of basis functions and k-points used for integrations in the two-dimensional BZ has been carefully checked.

MC and spin dynamics calculations

The MC simulations have been performed based on the Metropolis algorithm. We chose a (100 × 100) spin lattice for Pd(fcc)/Fe/Ir(111) and a cell of (200 × 200) for Pd(hcp)/Fe/Ir(111) with periodic boundary conditions. For both Pd stackings, the ground state at T=0 K and B=0 T has been found starting from a high temperature of 200 K or by imposing the spin spiral ground state as obtained from DFT. The latter approach has been found to be favourable as it minimizes the number of domains in the simulation. The spin spiral ground state was then used as a starting configuration for all other finite magnetic field simulations. The spin spiral ground state is heated to a temperature of T=200 K under applied magnetic field and cooled down in steps of 10 K. In these simulations, 108 MC steps were used at each temperature step to thermalize the system and the different physical quantities (magnetization, energy, topological charge and so on) were calculated by averaging using 104 steps. Particular attention was given to the hexagonal skyrmion lattice for which both systems were carefully relaxed by steps of 1 or 5 K below 60 K. For this particular configuration 2 × 109 MC steps were used to thermalize the system at every temperature step.

To further investigate the ground states at 0.5 K, we have developed a standard spin dynamics code that integrates the equation of motion:

where β is the damping term. We have observed that the energy is a constant of time when the equations of motion are integrated. When the starting configuration was not the ground state, we observed by integrating the equation of motion oscillations of the energy depending on the damping showing a lowering of the force field but an increase of the kinetic energy due to the rotation of the magnetic moments. Therefore both techniques give the same ground state.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Dupé, B. et al. Tailoring magnetic skyrmions in ultra-thin transition metal films. Nat. Commun. 5:4030 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5030 (2014).

References

Bogdanov, A. N. & Yablonskii, D. A. Thermodynamically stable ‘vortices’ in magnetically ordered crystals. The mixed state of magnets. Sov. Phys. JETP 68, 101–103 (1989).

Bogdanov, A. N. & Hubert, A. Thermodynamically stable magnetic vortex states in magnetic crystals. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 138, 255–269 (1994).

Bogdanov, A. N. & Rößler, U. K. Chiral symmetric breaking in magnetic thin films and multilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 037203 (2001).

Rößler, U. K., Bogdanov, A. N. & Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature 442, 797–801 (2006).

Mühlbauer, S. et al. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 323, 915–919 (2009).

Pappas, C. et al. Chiral Paramagnetic Skyrmion-like Phase in MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 197202 (2009).

Moskvin, E. et al. Complex chiral modulations in FeGe close to magnetic ordering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 077207 (2013).

Yu, X. Z. et al. Real space observation of a two-dimensional skyrmion crystal. Nature 465, 901–904 (2010).

Yu, X. Z. et al. Near room-temperature formation of a skyrmion crystal in thin-films of the helimagnet FeGe. Nat. Mat 10, 106–109 (2010).

Seki, S., Yu, X. Z., Ishiwata, S. & Tokura, Y. Observation of skyrmions in a multiferroic material. Science 336, 198–201 (2012).

Heinze, S. et al. Spontaneous atomic-scale magnetic skyrmion lattice in two dimensions. Nat. Phys. 7, 713–719 (2011).

Romming, N. et al. Writing and deleting single skyrmions. Science 341, 636–639 (2013).

Butenko, A. B., Leonov, A. A., Rößler, U. K. & Bogdanov, A. N. Stabilization of skyrmion textures by uniaxial distortions in noncentrosymmetric cubic helimagnets. Phys. Rev. B 82, 052403 (2010).

Kiselev, N. S., Bogdanov, A. N., Schäfer, R. & Rößler, U. K. Chiral skyrmions in thin magnetic films: new objects for magnetic storage technology? J. Phys. D 44, 392001 (2011).

Fert, A., Cros, V. & Sampaio, J. Skyrmions on the track. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 152–156 (2013).

Lee, M., Kang, W., Onose, Y., Tokura, Y. & Ong, N. P. Unusual Hall effect anomaly in MnSi under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 186601 (2009).

Neubauer, A. et al. Topological Hall effect in the A phase of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 186602 (2009).

Jonietz, F. et al. Spin transfer torques in MnSi at ultralow current densities. Science 330, 1648–1651 (2010).

Yu, X. Z. et al. Skyrmion flow near room temperature in an ultralow current density. Nat. Commun. 3, 988 (2012).

Schulz, T. et al. Emergent electrodynamics of skyrmions in a chiral magnet. Nat. Phys. 8, 301–304 (2012).

Iwasaki, J., Mochizuki, M. & Nagaosa, N. Universal current-velocity relation of skyrmion motion in chiral magnets. Nat. Commun. 4, 1463 (2013).

Iwasaki, J., Mochizuki, M. & Nagaosa, N. Current-induced skyrmion dynamics in constricted geometries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 742–747 (2013).

Sampaio, J., Cros, V., Rohart, S., Thiaville, A. & Fert, A. Nucleation, stability, and current-induced motion of isolated magnetic skyrmions in nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 839–844 (2013).

Dzyaloshinskii, I. E. Thermodynamic theory of ‘weak’ ferromagnetism in antiferromagnetic substances. Sov. Phys. JETP 5, 1259–1262 (1957).

Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 120, 91–98 (1960).

Fert, A. & Levy, P. A. Role of anisotropic exchange interactions in determining the properties of spin glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 44, 1538–1541 (1980).

Bode, M. et al. Chiral magnetic order at surfaces driven by inversion asymmetry. Nature 447, 190–193 (2007).

Kurz, Ph., Förster, F., Nordström, L., Bihlmayer, G. & Blügel, S. Ab initio treatment of noncollinear magnets with the full-potential linearized augmented plane wave method. Phys. Rev. B 69, 024415 (2004).

Heide, M., Bihlmayer, G. & Blügel, S. Describing Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya spirals from first-principles. Physica B 404, 2678 (2009).

Berg, B. & Lüscher, M. Definition and statistical distribution of a topological number in the lattice O(3) σ-model. Nucl. Phys. B 190, 412 (1981).

Heinze, S. Simulation of spin-polarized scanning tunneling microscopy images of non-collinear spin structures. Appl. Phys. A 85, 407 (2006).

Han, J. H., Zang, J., Yang, Z., Park, J.-H. & Nagaosa, N. Skyrmion lattice in a two-dimensional chiral magnet. Phys. Rev. B 82, 094429 (2010).

Hardrat, B. et al. Complex magnetism of Fe monolayers on hexagonal transition-metal surfaces from first-principles. Phys. Rev. B 79, 094411 (2009).

De Santis, M. et al. Structure and magnetic properties of Mn/Pt(110)-(1 × 2): A joint x-ray diffraction and theoretical study. Phys. Rev. B 75, 205432 (2007).

Acknowledgements

B.D. and S.H. thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for financial support under project HE3292/8-1. We gratefully acknowledge the HLRN for providing computer time. It is our pleasure to thank N. Kiselev, G. Bihlmayer, S. Blügel, P. Ferriani, N. Romming, A. Kubetzka, K. von Bergmann, Ch. Hanneken and R. Wiesendanger for many fruitful discussions. S.H. thanks the members of the Peter Grünberg Institut of the Forschungszentrum Jülich for their hospitality during his stay.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.D. and M.H. performed the density functional theory calculations. B.D. and C.P. carried out the Monte Carlo simulations. B.D., M.H., C.P. and S.H. analysed the data. B.D. and S.H. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-3, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Notes 1-3 and Supplementary References (PDF 485 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dupé, B., Hoffmann, M., Paillard, C. et al. Tailoring magnetic skyrmions in ultra-thin transition metal films. Nat Commun 5, 4030 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5030

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5030

This article is cited by

-

Topology-induced chiral photon emission from a large-scale meron lattice

Nature Electronics (2023)

-

Genetic-tunneling driven energy optimizer for spin systems

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Lifetime of coexisting sub-10 nm zero-field skyrmions and antiskyrmions

npj Quantum Materials (2023)

-

Infinite critical boson non-Fermi liquid on heterostructure interfaces

Quantum Frontiers (2023)

-

Emergence of zero-field non-synthetic single and interchained antiferromagnetic skyrmions in thin films

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.