Abstract

Reconstruction of atmospheric CO2 during times of past abrupt climate change may help us better understand climate-carbon cycle feedbacks. Previous ice core studies reveal simultaneous increases in atmospheric CO2 and Antarctic temperature during times when Greenland and the northern hemisphere experienced very long, cold stadial conditions during the last ice age. Whether this relationship extends to all of the numerous stadial events in the Greenland ice core record has not been clear. Here we present a high-resolution record of atmospheric CO2 from the Siple Dome ice core, Antarctica for part of the last ice age. We find that CO2 does not significantly change during the short Greenlandic stadial events, implying that the climate system perturbation that produced the short stadials was not strong enough to substantially alter the carbon cycle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ice core records from Greenland reveal a detailed history of abrupt climate change during the last glacial period. Warm and cold periods (interstadial and stadial, respectively) repeated on millennial timescales but rapid switches between the two happened in decades1,2,3,4. Antarctic ice core records, however, reveal gradual warming during Geenlandic stadials and cooling during interstadials5,6. The out-of-phase interhemispheric climate relationship is usually referred to as the ‘bipolar seesaw’7 and the most popular hypothesis for the control mechanism includes reorganization of ocean-atmosphere circulation and change in meridional heat transport, possibly caused by fresh water input into the North Atlantic8,9,10.

Reconstruction of atmospheric CO2 during abrupt climate change events may help us better understand climate-carbon cycle feedbacks and provide data for testing carbon cycle models under variety of boundary conditions. Existing Antarctic ice core records show CO2 increases during long Greenlandic stadials, which are also accompanied by major Antarctic warmings11,12. Ventilation of CO2-rich deep water in the Southern Ocean may have controlled ocean-atmosphere carbon exchange and therefore atmospheric CO2 concentration13. Marine sediment records from the Southern Ocean indicate increased opal flux14 and reduced stratification15 during the Younger Dryas event and the long stadial preceding the Bølling-Allerød event14,15, both times of rising CO2, and can be interpreted as a record of increased upwelling and CO2 outgassing in the Southern Ocean14,15. During the same time intervals, the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) was reduced and the Antarctic temperature gradually increased16,17. During the long stadials of the last ice age, marine sediment records indicate shoaled AMOC18 and increased opal flux14 in the Southern Ocean, although the chronology of the proxy for the latter is not well constrained. The shoaling of AMOC likely coincided with reduction in AMOC strength that might have caused reduction in northward oceanic heat transport, the gradual warming in Antarctica and CO2 outgassing from the Southern ocean during the long stadials10,14, analogous to the early stage of the last deglacial Antarctic warming and CO2 increase14,19,20.

High-resolution records from the EPICA Dronning Maud Land (EDML) ice core in east Antarctica show the ‘bipolar seesaw’ operated not only during the major long stadials but also during other short ones, and that stadial duration is positively correlated with the magnitude of the temperature increase in Antarctica. These observations support the hypothesis of reduction in AMOC during both long and short stadials21, although there is no clear marine evidence of AMOC reduction during each of the short stadials, perhaps owing to insufficient data resolution and/or chronology6.

By analogy to the relationship between CO2 and major Antarctic warmings/long Greenlandic stadials, we might expect small CO2 increases during the small Antarctic warmings/short Greenlandic stadials. However, atmospheric CO2 change during the short stadials is not well resolved in existing ice core records owing to low temporal data resolution (280–570 years11,12,22).

We investigate CO2 variations during the short Greenlandic stadials, with a multi-decadal to centennial CO2 record with a mean sampling resolution of 95 years, from the Siple Dome ice core, Antarctica. Our new results cover the time interval of Greenlandic abrupt climate events (Dansgaard-Oeschger or DO events) DO2–7 and our sampling resolution is sufficient to examine CO2 trends during the short stadials lasting for 800–1200 years. Combined with recently published high-resolution data for DO8–10 from the same core23, we constructed a complete high-resolution CO2 record from 22 to 41 ka.

Results

Natural smoothing of gas records in the Siple Dome ice core

Snow accumulation rates at the Siple Dome are relatively high, and therefore smoothing of gas records by diffusion and gradual bubble close-off in the firn (unconsolidated snow layer on the top of ice sheet) is relatively small24. The high snow accumulation rates also result in a small uncertainty in the relative timing between gas ages and ice ages (Δage)25, allowing better comparison of gas records with temperature proxy records24. A firn densification model for Siple Dome shows Δage of 500–1000 years during the 22–41-ka period24. Because the width of the gas age distribution at half-height is typically about 10% of Δage25,26,27,28, we estimate the gas age distribution of the Siple Dome record to be <100 years during the time interval of study. The sharp increases in the Siple Dome CH4 record (Fig. 1) clearly confirm that the smoothing of gas records is minimal on multi-centennial timescales and supports our estimation of smoothing of the Siple Dome CO2 record.

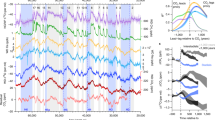

(a) Greenlandic isotopic temperature record from the NGRIP ice core57. Black numbers represent Dansgaard-Oeschger events. HS stands for Heinrich stadial, indicating long stadials that include Heinrich events. (b) Atmospheric CH4 records from Greenland (grey)21, Siple Dome (red)24 and EDML (blue)21 ice cores. Black dots are new Siple Dome CH4 data (this study). Red triangles indicate age control points. (c) Atmospheric CO2 record from Siple Dome, Antarctica ice core (this study). Red line represents 300-year running means of the CO2 record. Black dots are published records23. (d) Antarctic temperature proxy records from Siple Dome (dark blue)24 and EDML (grey)21 ice cores. All the ages are synchronized on Greenland Ice Core Chronology 2005 (GICC05) timescale. Blue and pink boxes indicate time intervals of short and long stadials (Greenlandic cold spans), respectively. During those stadials, Antarctic temperature increased.

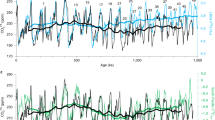

Two modes of CO2 change during Greenlandic stadials

As shown in Fig. 1, we observe small CO2 variations of ~5 p.p.m. on centennial timescales during the short stadials. A 300-year running mean (red curve) removes these features (Fig. 1), illustrating that CO2 change was negligible on multi-centennial timescales. We observe small decreases on longer timescales during most of the short stadials (Fig. 1), but these are part of a long-term trend. After detrending it becomes clear that the CO2 change associated with short stadials themselves is insignificant (Fig. 2a). In contrast, we observe CO2 increases during the long stadials, confirming previous results from different Antarctic ice cores11,12,22,29 (Fig. 2a). The isotopic temperature proxy (δDice) from the Siple Dome ice core shows small Antarctic warmings during most of the short stadials (Fig. 2b) and confirms previous results from the EDML ice core21, implying that the small Antarctic warmings during the short stadials are not only local features but at least of larger regional extent because Siple Dome is located in the Pacific sector, while the EDML core is in the Atlantic sector in Antarctica. Combining the Siple Dome CO2 and climate records, we plot the time evolution of CO2 versus the temperature proxy (δDice) anomalies during Greenlandic stadials or Antarctic warmings, using the detrended Siple Dome CO2 and temperature proxy records for short stadials (Fig. 2c). We find that CO2 and δDice anomalies are not significantly correlated during the short stadials (average r=0.0), but positively correlated during the long stadials (average r=0.84) (Fig. 2c). A slight temperature decrease in the Siple Dome δDice between DO9 and 10 is not confirmed in the EDML isotopic temperature (δOice) record21 and excluded in our calculation. We note that Siple Dome isotopic temperature (δDice) between DO3 and 4 increases, but at EDML it decreases, presumably owing to local effects. Our finding of the two different modes of CO2 change during Greenlandic stadials for the period 22–41 ka is consistent with the results of a recent, lower resolution study of CO2 variations from 38 to 115 ka12, which shows <5 p.p.b. variations in CO2 during the short stadial events of marine isotope stage 3.

(a) CO2 change during Greenlandic stadials from Siple Dome (solid lines) (this study) and Talos Dome (dashed lines)12 ice core records. DO numbers indicate DO warmings at the end of the stadials. (b) Antarctic temperature proxy record during stadials from Siple Dome ice core24. (c) Time evolution of atmospheric CO2 versus isotopic temperature anomalies during stadials. Derived from (a,b). The pale red and blue ellipses indicate records for Heinrich (long) and non-Heinrich (short) stadials, respectively. Three hundred-year running means are used for both CO2 and isotopic temperature proxy records. In order to remove multi-millennial changes during short Greenlandic stadials, the Siple Dome CO2 and isotopic temperature records are detrended.

Discussion

The small-to-insignificant CO2 change during the short stadials may imply that AMOC perturbations happened at these events but were too short to result in a change in atmospheric CO2. If this were the case, we would expect to observe no CO2 increase during the first 800–1200 years of the long stadials, because duration of the short stadials ranges 800–1200 years. However, we observe that CO2 increases from the beginning of the long Greenlandic stadials predating DO8 and DO4 (Fig. 2a). The time lag of CO2 relative to the isotopic signal during Greenlandic stadials predating DO12 and 17 from other ice core records appears small as well11,12. However, we cannot clearly rule out the possibility of a time lag of several centuries (Fig. 3). In addition, there is some ambiguity about the start of the long stadial predating DO4, which is conventionally defined by the end of a small temperature proxy peak (DO4.1)21. We follow convention here, but note that additional high-resolution data from other long stadial events will be needed to further address the question of when CO2 starts to rise during events of this type. The above observation suggests that climate perturbations associated with the long and short stadials are different. Cave deposits reveal less weakening in the Asian monsoon30 and less intense South American monsoon31 during the short stadials compared with the long stadials, suggesting that the perturbation to the climate system related to the short stadial events in Greenland was weaker than for the long ones. A comparison of Antarctic ice core climate records with a thermodynamic model also indicates that the long stadials were caused by a stronger climate perturbation than short ones32. Finally, although it is not conclusive, δ13C in benthic foraminifera from North Atlantic sediment cores indicates less shoaling of AMOC during short stadials than that during the long stadials33. Thus it is likely that strength of the climate perturbation is related to change in atmospheric CO2 during the Greenlandic stadials. Massive iceberg discharge events in the North Atlantic (Heinrich events) occurred within time intervals of the long stadials. The Heinrich events could have increased fresh water forcing into the North Atlantic and also caused large perturbations to atmospheric circulation (for example, southward movement of the ITCZ34). However, multiple studies suggest that the Heinrich events lag onsets of long stadials35,36, although exact timing of those events within the stadials is not well constrained37,38.

(a–d) Ice core records extended from Fig. 1. Siple Dome CO2 and CH4 records are compared with existing low-resolution records from EPICA EDML12,21, Byrd11 and Talos11,58 ice cores, Antarctica. Age intervals for HS2 and HS5a are not well constrained owing to chronological uncertainty in the paleoproxy records.

The control mechanisms for the two CO2 modes may exist in oceanic processes such as AMOC reduction and consequent upwelling in the Southern Ocean. Those oceanic processes can be linked by change in vertical salinity transport and stratification in the Southern Ocean39 and/or latitudinal shift of Southern Hemisphere Westerlies14,40 and/or strength of the Southern Hemisphere Westerlies41,42,43. Although we cannot pinpoint a precise oceanic mechanism, we speculate that the weakening in AMOC during the short stadials might have not been sufficient to cause enough of a change in upwelling to impact atmospheric CO2. Marine proxy data for upwelling in the Southern Ocean do not clearly show strong peaks in between long stadials that bracket several short stadials14, supporting this hypothesis.

Other potential oceanic mechanisms that change CO2 outgassing include variations in sea ice extent and changes in iron fertilization in the Southern Ocean44. Sea-salt-Na may be a proxy for sea ice extent, but Siple Dome, Dome C and EDML ice core records do not show significant differences between long and short Greenlandic stadials44,45. Proxy records for the Fe-flux (non-sea-salt Ca) from Dome C and EDML cores show highly reduced Fe-flux during several long Greenlandic stadials that predate DO8, but after DO8 the reduction during long stadials is not larger than that during short stadials44. Thus a difference in iron fertilization in the Southern Ocean is not likely the main cause of the two modes in CO2 change.

Atmospheric CO2 can be also controlled by exchange of land carbon. Terrestrial carbon is mostly affected by temperature and precipitation because they both control vegetation and organic carbon in soil. Compared with interstadials, paleoproxy data for both short and long stadials indicate colder and dryer conditions in the northern hemisphere, and warmer and wetter conditions in the southern hemisphere, although the magnitude of those changes depends on the type of stadials6. However, model simulations predict either a decrease46,47 or increase48 in land carbon during the stadials. Although we cannot rule out terrestrial control on the two modes of CO2 change, we suggest that the control mechanism exists more likely in the ocean rather than on land, because we have supporting evidence for an oceanic CO2 source during the long stadials in the last deglacial period14,15,49,50.

In principle, the lack of change in atmospheric CO2 could also result from compensating changes in sources (for example, coincident terrestrial uptake and oceanic release) as predicted in models of AMOC shutdown and carbon cycle response46,47,51. However, the global impact of short stadials on the terrestrial biosphere was probably small, given that paleoproxy records indicate weaker terrestrial climate perturbations during the short Greenlandic stadials compared with the long ones30,31 as discussed above. Thus, terrestrial uptake balancing oceanic release during the short Greenlandic stadials is not likely the main explanation for the lack of CO2 response.

Our new high-resolution record defines two modes of millennial scale CO2 change during stadial events in the northern hemisphere that depend on the nature of the Greenlandic stadial. During short Greenlandic stadials, those not associated with Heinrich events, it is likely that the impact on ocean circulation was not sufficient to release CO2 from deep ocean to the atmosphere. The lack of correlation between CO2 and Antarctic temperature change during the short stadials implies that links between Antarctic climate change and high-latitude northern hemisphere climate may have been controlled by shallow oceanic and/or atmospheric processes, while CO2 change was controlled by deep oceanic and Southern Ocean processes.

Methods

CO2 concentration measurement

For CO2 analysis at the Oregon State University, samples were placed in a double-walled stainless steel chamber at −35 °C, cooled using cold ethanol circulation between the walls, evacuated for 13 min and then crushed with steel pins. Air liberated from the ice was dried in a cold stainless steel coil at −85 °C and then trapped in ~6 cm3 stainless steel sample tubes at −262 °C. After warming the trapped air to room temperature, the CO2 mixing ratio was measured with an Agilent 6890N Gas Chromatograph (GC) with a flame ionization detector, with nickel catalyst conversion of CO2 to CH4 before measurement. Daily calibration curves used several measurements of standard air with 197.54 p.p.m. CO2 (WMOX2007 CO2 mole fraction scale). Daily corrections for the dry extraction and GC analysis were done using several standard airs (197.54 p.p.m.) that were introduced over the ice samples and trapped in sample tubes mimicking the procedure of the air samples from ice. We compared 2–5 replicates from the same depths. Details of the methods are described in ref. 52. The s.e. for replicates from the same depth averaged 0.6 p.p.m. for the Siple Dome ice. The excellent agreement among the replicates were achieved by careful trimming of the ice surface and improved analytical techniques52 since our early analysis for the same core a decade ago at Scripps Institution of Oceanography53.

CH4 concentration measurement

CH4 analysis was separately performed at the Oregon State University54. Duplicate samples with a weight of ~60 g for each were analysed for each depth interval. Samples were placed in cold glass flasks bathed in an ethanol bath at −64.5 °C. The flasks with the ice samples were evacuated for 1 h. The flasks valves were closed and then the ice was melted in a warm water bath. After melting, the flasks were submerged in the cold ethanol bath to refreeze the ice melt. Air liberated from each ice sample was analysed four times with an Agilent 6890N GC with a flame ionization detector. Data are reported on the NOAA04 methane concentration scale.

Synchronization of ice core records

Our CO2 record from the Siple Dome core is synchronized with NGRIP (North Greenland Ice Core Project) ice ages on the Greenland Ice Core Chronology 2005 (GICC05) timescale55 using abrupt CH4 changes that are near synchronous with abrupt Greenlandic climate change56. We used updated CH4 records to make better synchronization. The CH4 data resolution is 82 and 232 years for 23.5–42.3 and 42.3–46.9 ka, respectively. The GICC05 timescale is based on layer counting of Greenland ice cores and agrees well with other absolute ages such as cave deposit records55. At DO2, the correlation between CH4 increase and Greenlandic warming is not clear, and thus we correlate Siple Dome CH4 with the NGRIP CH4 record. The age tie points are listed in Table 1 and their uncertainty is controlled primarily by the CH4 data resolution. The age differences were linearly interpolated at depths between the tie points, and we reconstructed new ages at those depths by adding the calculated difference to the original ages24. Synchronized ice ages were determined using published estimates of ice age-gas age difference24.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Ahn, J. & Brook, E.J. Siple Dome ice reveals two modes of millennial CO2 change during the last ice age. Nat. Commun. 5:3723 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4723 (2014).

References

Dansgaard, W. et al. Evidence for general instability of past climate from a 250-kyr ice-core record. Nature 364, 218–220 (1993).

Grootes, P. M., Stuiver, M., White, J. W. C., Johnsen, S. J. & Jouzel, J. Comparison of oxygen isotope records from the GISP2 and GRIP Greenland ice cores. Nature 366, 552–554 (1993).

Steffensen, J. P. et al. High-resolution Greenland ice core data show abrupt climate change happens in few years. Science 321, 680–684 (2008).

Thomas, E. R. et al. Anatomy of a Dansgaard-Oeschger warming transition: high-resolution analysis of the North Greenland Ice Core Project ice core. J. Geophys. Res. 114, D08102 (2009).

Blunier, T. & Brook, E. J. Timing of millennial-scale climate change in Antarctica and Greenland during the last glacial period. Science 291, 109–112 (2001).

Clement, A. C. & Peterson, L. C. Mechanisms of abrupt climate change of the last glacial period. Rev. Geophys. 46, RG4002 (2008).

Broecker, W. S. Paleocean circulation during the last deglaciation: a bipolar seesaw? Paleoceanography 13, 119–121 (1998).

Crowley, T. J. North Atlantic deep water cools the southern hemisphere. Paleoceanography 7, 489–497 (1992).

Schmittner, A., Saenko, O. A. & Weaver, A. J. Coupling of the hemispheres in observations and simulations of glacial climate change. Quat. Sci. Rev. 22, 659–671 (2003).

Stocker, T. F. & Johnsen, S. J. A minimum thermodynamic model for the bipolar seesaw. Paleoceanography 18, 1087 (2003).

Ahn, J. & Brook, E. J. Atmospheric CO2 and climate on millennial time scales during the last glacial period. Science 322, 83–85 (2008).

Bereiter, B. et al. Mode change of millennial CO2 variability during the last glacial cycle associated with a bipolar marine carbon seesaw. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 9755–9760 (2012).

Sigman, D. M., Hain, M. P. & Haug, G. H. The polar ocean and glacial cycles in atmospheric CO2 concentration. Nature 466, 47–55 (2010).

Anderson, R. F. et al. Wind-driven upwelling in the Southern Ocean and the deglacial rise in atmospheric CO2 . Science 323, 1443–1448 (2009).

Skinner, L. C., Fallon, S., Waelbroeck, C., Michel, E. & Barker, S. Ventilation of the deep Southern Ocean and deglacial CO2 rise. Science 328, 1147–1151 (2010).

McManus, J. F., Francois, R., Cherardi, J.-M., Keigwin, L. D. & Brown-Leger, S. Collapse and rapid resumption of Atlantic meridional circulation linked to deglacial climate changes. Nature 428, 834–837 (2004).

Lynch-Stieglitz, J., Curry, W. B. & Slowey, N. Weaker Gulf stream in the Florida straits during the last glacial maximum. Nature 402, 644–648 (1999).

Shackleton, N. J., Hall, M. A. & Vincent, E. Phase relationships between millennial-scale events 64,000-24,000 years ago. Paleoceanography 15, 565–569 (2000).

Pedro, J. B., Rasmussen, S. O. & van Ommen, T. D. Tightened constraints on the time-lag between Antarctic temperature and CO2 during the last deglaciation. Clim. Past 8, 1213–1221 (2012).

Parrenin, F. et al. CO2 and Antarctic temperature during the last deglacial warming. Science 339, 1060–1063 (2013).

EPICA Community members. One-to-one coulpling of glacial climate variability in Greenland and Antarctica. Nature 444, 195–198 (2006).

Indermühle, A., Monnin, E., Stauffer, B., Stocker, T. F. & Wahlen, M. Atmospheric CO2 concentration form 60 to 20 kyr BP from the Taylor Dome ice core, Antarctica. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 735–738 (2000).

Ahn, J., Brook, E. J., Schmittner, A. & Kreutz, K. Abrupt change in atmospheric CO2 during the last ice age. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L18711 (2012).

Brook, E. J. et al. Timing of millennial-scale climate change at Siple Dome, West Antarctica, during the last glacial period. Quat. Sci. Rev. 24, 1333–1343 (2005).

Schwander, J. et al. Age scale of the air in the summit ice: Implication for glacial-interglacial temperature change. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 19483–19493 (1997).

Trudinger, C. M. et al. Modeling air movement and bubble trapping in firn. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 6747–6763 (1997).

Monnin, E. et al. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations over the last glacial termination. Science 291, 112–114 (2001).

Ahn, J., Brook, E. J. & Buizert, C. Response of atmospheric CO2 to the abrupt cooling event 8200 years ago. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 604–609 (2014).

Ahn, J. & Brook, E. J. Atmospheric CO2 and climate from 65 to 30 ka B.P. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L10703 (2007).

Wang, Y. J. et al. A high-resolution absolute-dated late Pleistocene monsoon record from Hulu cave, China. Science 294, 2345–2348 (2001).

Kanner, L. C., Burns, S. J., Cheng, H. R. & Edwards, L. High-latitude forcing of the South American summer monsoon during the last glacial. Science 335, 570–573 (2012).

Margari, V. et al. The nature of millennial-scale climate variability during the past two glacial periods. Nat. Geosci. 3, 127–131 (2010).

Elliot, M., Labeyrie, L. & Duplessy, J.-C. Changes in North Atlantic deep-water formation associated with the Dansgaard-Oeschger temperature oscillations (60-10 ka). Quat. Sci. Rev. 21, 1153–1165 (2002).

Chiang, J. C., Biasutti, M. & Battisti, D. S. Sensitivity of the Atlantic intertropical convergence zone to last glacial maximum boundary conditions. Paleoceanography 18, 1094 (2003).

Clark, P., Hostetler, S. W., Pisias, N. G., Schmittner, A. & Meissner, K. J. in Ocean Circulation: Mechanisms and Impacts, Vol. 173 (eds Andreas Schmittner, John Chiang & Sidney Hemming) 209–246 (AGU Geophysical Monograph Series, 2007).

Marcott, S. et al. Ice-shelf collape from subsurface warming as a trigger for Heinrich events. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13415–13419 (2011).

Sarnthein, M. et al. in The Northern North Atlantic: A Changing Envrionment (eds Schäfer, P., Schlüter, M., Ritzrau, W. & Thiede, J.) 365–410 (Springer, 2001).

Hemming, S. Heinrich events: massive late Pleistocene detritus layers of the North Atlantic and their global climate imprint. Rev. Geophys. 42, RG1005 (2004).

Schmittner, A., Brook, E. J. & Ahn, J. in Ocean Circulation: Mechanisms and Impacts Vol. 173 (esds Andreas Schmittner, John Chiang & Sidney Hemming) 315–334 (AGU Geophysical Monograph Series, 2007).

Toggweiler, J. R., Russell, J. L. & Carson, S. R. Midlatitude westerlies, atmospheric CO2, and climate change during the ice ages. Paleoceanography 21, PA2005 (2006).

Tschumi, T., Joos, F. & Parekh, P. How important are Southern Hemisphere wind changes for low glacial carbon dioxide? A model study. Paleoceanography 23, PA4208 (2008).

Menviel, L., Timmermann, A., Mouchet, M. & Timm, O. Meridional reorganizations of marine and terrestrial productivity during Heinrich events. Paleoceanography 23, PA4201 (2008).

d’Orgeville, M., Sijp, W. P., England, M. H. & Meissner, K. J. On the control of glacial-interglacial atmospheric CO2 variations by the Southern Hemisphere westerlies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L21703 (2010).

Fischer, H. et al. Reconstruction of millennial changes in dust emission, transport and regional sea ice coverage using the deep EPICA ice cores from the Atlantic and Indian Ocean sector of Antarctica. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 260, 340–354 (2007).

Mayewski, P. A. et al. State of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean climate system. Rev. Geophys. 47, RG1003 (2009).

Bozbiyik, A., Steinacher, M., Joos, F., Stocker, T. F. & Menviel, L. Fingerprints of changes in the terrestrial carbon cycle in response to large reorganizations in ocean circulation. Clim. Past 7, 319–338 (2011).

Menviel, L., Timmermann, A., Mouchet, M. & Timm, O. Meridional reorganizations of marine and terrestrial productivity during Heinrich events. Paleoceanography 23, PA1203 (2008).

Köhler, P., Joos, F., Gerber, S. & Knutti, R. Simulated changes in vegetation distribution, land carbon storage, and atmospheric CO2 in response to a collapse of the North Atlantic thermohaline circulation. Clim. Dynamics. 25, 689–708 (2005).

Schmitt, J. et al. Carbon isotope constraints on the deglacial CO2 rise from ice cores. Science 336, 711–714 (2012).

Burke, A. & Robinson, L. F. The Southern Ocean’s role in carbon exchange during the last deglaciation. Science 335, 557–561 (2012).

Schmittner, A. & Galbraith, E. D. Glacial greenhouse-gas fluctuations controlled by ocean circulation changes. Nature 456, 373–376 (2008).

Ahn, J., Brook, E. J. & Howell, K. A high-precision method for measurement of paleoatmospheric CO2 in small polar ice samples. J. Glaciol. 55, 499–506 (2009).

Ahn, J. et al. A record of atmospheric CO2 during the last 40,000 years from the Siple Dome, Antarctica ice core. J. Geophys. Res. 109, D13305 (2004).

Mitchell, L. E., Brook, E. J., Sowers, T., McConnell, J. R. & Taylor, K. Multidecadal variability of atmospheric methane, 1000-1800 C.E. J. Geophys. Res. 116, G02007 (2011).

Svensson, A. et al. A 60 000 year Greenland stratigraphic ice core chronology. Clim. Past 4, 47–57 (2008).

Huber, C. et al. Isotope calibrated Greenland temperature record over Marine Isotope Stage 3 and its relation to CH4. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 243, 504–519 (2006).

North Greenland Ice Core Project members. High-resolution record of Northern Hemisphere climate extending into the last interglacial period. Nature 431, 147–151 (2004).

Schüpbach, S., Federer, U., Bigler, M., Fischer, H. & Stocker, T. F. A refinded TALDICE-1a age scale from 55 to 112 ka before present for the Talos Dome ice core based on high-resolution methane measurements. Clim. Past 7, 1001–1009 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Kalk for analytical assistance and the staff of the National Ice Core Lab for ice sampling and curation. We also thank Andreas Schmittner and Luke Skinner for helpful discussions. Financial support was provided by the National Science Foundation Grant OPP 0944764. This work was also supported by Polar Academic Program (PAP, PD12010) of the Korea Polar Research Institution (KOPRI) research grant and Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2011-0025242). The data will be available at NSIDC (National Snow and Ice Data Center) and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Palaeoclimatology websites.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A. designed and carried out the experiments. All authors interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Data 1

Siple Dome ice core CO2 record (XLSX 34 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ahn, J., Brook, E. Siple Dome ice reveals two modes of millennial CO2 change during the last ice age. Nat Commun 5, 3723 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4723

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4723

This article is cited by

-

Millennial atmospheric CO2 changes linked to ocean ventilation modes over past 150,000 years

Nature Geoscience (2023)

-

Reconstructing the post-LGM deglacial history of Hollingsworth Glacier on Ricker Hills, Transantarctic Mountains, Antarctica

Journal of Mountain Science (2022)

-

Direct astronomical influence on abrupt climate variability

Nature Geoscience (2021)

-

Globally resolved surface temperatures since the Last Glacial Maximum

Nature (2021)

-

A salty deep ocean as a prerequisite for glacial termination

Nature Geoscience (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.