Abstract

Optical and electrical control of the nuclear spin system allows enhancing the sensitivity of NMR applications and spin-based information storage and processing. Dynamic nuclear polarization in semiconductors is commonly achieved in the presence of a stabilizing external magnetic field. Here we report efficient optical pumping of nuclear spins at zero magnetic field in strain-free GaAs quantum dots. The strong interaction of a single, optically injected electron spin with the nuclear spins acts as a stabilizing, effective magnetic field (Knight field) on the nuclei. We optically tune the Knight field amplitude and direction. In combination with a small transverse magnetic field, we are able to control the longitudinal and transverse components of the nuclear spin polarization in the absence of lattice strain—that is, in dots with strongly reduced static nuclear quadrupole effects, as reproduced by our model calculations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The investigation of dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) effects in bulk semiconductors1,2, in quantum wells3,4 and in quantum dots (QDs)5,6 under circularly polarized light excitation has been a very active field of research for more than 30 years, both from a fundamental point of view and for potential applications in quantum computing and NMR imaging7,8. Electrical control of the nuclear spins allows to access complementary information9,10. These effects, predicted originally for metals11, manifest themselves by giant hyperfine fields of nuclear origin experienced by localized electrons12 and can influence their spin polarization in the same way as an external magnetic field. In unstrained bulk III–V semiconductors, the magnitude13,14 and the orientation15 of the nuclear magnetization, and therefore of the large hyperfine nuclear field Bn, can be manipulated in a small external magnetic field, of the order of the local field BL (≈0.15 mT in bulk GaAs12), which characterizes nuclear spin–spin interactions, see Fig. 1a.

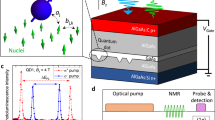

(a) Hyperfine interaction between a single electron and the nuclear spins of the quantum dot lattice. (b) Circular polarization degree of emission (error ±1% included in symbol height) of neutral exciton X0 (squares) and charged excitons X+ (triangles) and X− (circles) as a function of excitation laser power using σ+ polarization. (c) Energy difference between σ+ and σ− polarized emission for X+ (triangles) and X− (circles): Overhauser shift ∝ average nuclear spin ‹Iz›. Error bars correspond to spectral precision (d) X+PL spectra σ+ (triangles) and σ−(circles) polarized at max. laser power. (e) Overhauser shift as a function of the measured X+ PL polarization with varying laser excitation polarization at constant power of 2 μW. Error bars correspond to spectral precision.

The interactions among nuclear spins of the atoms that form a semiconductor QD are, in addition, strongly influenced by the presence of strain in the widely studied InGaAs/GaAs and InP/GaInP dots16,17. Static nuclear quadrupole splittings correspond to effective internal magnetic fields  of hundreds of mT. They are thought to be at the origin of intriguing nuclear spin physics, not observed in bulk structures, such as line dragging in absorption due to the non-collinear hyperfine interaction18,19, DNP at zero magnetic field20,21,22,23,24, the anomalous Hanle effect25,26 and the effective blocking of nuclear spin diffusion, see ch. 11 of the book by Dyakonov27. Controlling nuclear spin polarization is also important for semiconductor-based quantum emitters, usually operating at zero applied magnetic fields, as the Overhauser field and its fluctuations will alter the polarization basis of the emitted photons in entanglement experiments28,29. Strain is an inherent feature of all the samples grown in the Stranski–Krastanov (SK) growth mode, and the influence of the strong strain and strong quantum confinement on the hyperfine interaction cannot be separated experimentally.

of hundreds of mT. They are thought to be at the origin of intriguing nuclear spin physics, not observed in bulk structures, such as line dragging in absorption due to the non-collinear hyperfine interaction18,19, DNP at zero magnetic field20,21,22,23,24, the anomalous Hanle effect25,26 and the effective blocking of nuclear spin diffusion, see ch. 11 of the book by Dyakonov27. Controlling nuclear spin polarization is also important for semiconductor-based quantum emitters, usually operating at zero applied magnetic fields, as the Overhauser field and its fluctuations will alter the polarization basis of the emitted photons in entanglement experiments28,29. Strain is an inherent feature of all the samples grown in the Stranski–Krastanov (SK) growth mode, and the influence of the strong strain and strong quantum confinement on the hyperfine interaction cannot be separated experimentally.

Here we report efficient optical initialization of a nuclear spin polarization of ~10% at zero applied magnetic field in strain-free, isolated GaAs QDs (no wetting layer) grown by droplet epitaxy30. In transverse magnetic fields we are able to tilt the optically generated Overhauser field, in stark contrast to strained dots. This implies that in the absence of strain, static nuclear quadrupole effects are reduced by at least two orders of magnitude in GaAs/AlGaAs droplet dots, see Table 1 for comparison with strained dots and bulk GaAs. Effective nuclear spin polarization build-up is made possible by the very large Knight field Be on the order of 15 mT, the effective field experienced by the nuclei in the presence of a spin-polarized electron31. Rotation and tilting of a strong Overhauser field is usually achieved in systems such as donor-bound electrons in GaAs-bulk for which a spin temperature can be established1,32. Our model calculations show that to tilt the Overhauser field away from the optical axis the establishment of a global spin temperature in the dot is not strictly necessary. We show that strong Knight field gradients between one nucleus and its nearest neighbour can prevent both the establishment of a temperature and of spin diffusion among the nuclear spins throughout the dot33,34. Our findings suggest that zero field DNP can occur in other spintronic devices with highly polarized electrons such as gate-defined QDs35,36,37,38,39 and ferromagnet/semiconductor hybrid structures40,41.

Results

DNP at zero applied magnetic field

One of the outstanding features of QDs is the possibility to achieve DNP in zero external magnetic fields20,21,22,23,24. In Maletinsky et al.42, DNP was first constructed via optical pumping in the presence of a well-defined electron spin in a charge-tunable InGaAs QD. Subsequently, the electron was removed from the dot and the nuclear spin polarization remained stable in the absence of any electron spin. In this case the Knight field is also absent and strong static nuclear quadrupole effects in strained dots with alloy disorder have been put forward as the main source for stabilizing the nuclear spin system22,27.

Here as shown in Fig. 1c–e, we provide the first experimental evidence for substantial DNP in zero external field, in dots with strongly reduced  , see Table 1. All the results shown in the present work were taken in unstrained GaAs droplet dots with negligible alloy intermixing43. Our sample is subjected to charge fluctuations30,44, which can give rise to small (typ.

, see Table 1. All the results shown in the present work were taken in unstrained GaAs droplet dots with negligible alloy intermixing43. Our sample is subjected to charge fluctuations30,44, which can give rise to small (typ.  below 1 mT), fluctuating nuclear quadruple shifts45,46. During the 1-s photoluminescence (PL) integration time, we observe charged (X+ and X−) and neutral (X0) emission of a single QD. The X+ (two holes in a spin singlet, one electron) with a well-orientated electron spin can polarize the nuclei via the Fermi-contact hyperfine interaction, as the electron partially preserves its spin polarization during capture6. Note that the PL polarization of the X− (two electrons in a spin singlet, one hole) is negative in Fig. 1b—that is, cross-polarized with respect to the excitation laser47,48,49,50. The resident conduction electron left behind after X− recombination has therefore the same orientation as the conduction electron that exists during the radiative lifetime of the X+. The DNP resulting from this single electron (that will eventually tunnel out of the dot) and the DNP built up during the X+ radiative lifetime have the same direction, note also the very similar Overhauser shifts measured for X+ and X− in Fig. 1c. The contributions of the X+ and X− excitons to the nuclear polarization are thus additive. We can neglect the small contribution of the hole spin hyperfine interaction in a first approximation51,52,53. The neutral X0 will feel the nuclear field created by the charged excitons23. In the remainder of the paper we concentrate on the X+ exciton and hence focus on the interaction of the unpaired electron with the nuclei during the radiative lifetime, the mean electron spin is related to the X+ PL circular polarization degree ρ simply as ‹Sz›=−ρ/2 (see Methods).

below 1 mT), fluctuating nuclear quadruple shifts45,46. During the 1-s photoluminescence (PL) integration time, we observe charged (X+ and X−) and neutral (X0) emission of a single QD. The X+ (two holes in a spin singlet, one electron) with a well-orientated electron spin can polarize the nuclei via the Fermi-contact hyperfine interaction, as the electron partially preserves its spin polarization during capture6. Note that the PL polarization of the X− (two electrons in a spin singlet, one hole) is negative in Fig. 1b—that is, cross-polarized with respect to the excitation laser47,48,49,50. The resident conduction electron left behind after X− recombination has therefore the same orientation as the conduction electron that exists during the radiative lifetime of the X+. The DNP resulting from this single electron (that will eventually tunnel out of the dot) and the DNP built up during the X+ radiative lifetime have the same direction, note also the very similar Overhauser shifts measured for X+ and X− in Fig. 1c. The contributions of the X+ and X− excitons to the nuclear polarization are thus additive. We can neglect the small contribution of the hole spin hyperfine interaction in a first approximation51,52,53. The neutral X0 will feel the nuclear field created by the charged excitons23. In the remainder of the paper we concentrate on the X+ exciton and hence focus on the interaction of the unpaired electron with the nuclei during the radiative lifetime, the mean electron spin is related to the X+ PL circular polarization degree ρ simply as ‹Sz›=−ρ/2 (see Methods).

In the absence of any internal or applied magnetic field, the X+ transition shows a single line. As we increase the laser excitation power, a clear splitting between the circularly σ+ and σ− polarized components emerges (Overhauser shift), as seen in Fig. 1c,d. We measure an Overhauser shift of up to 16 μeV (see Fig. 1c–e), which corresponds to a nuclear polarization of 12%, taking into account that the Overhauser shift for 100% nuclear polarization in GaAs is 135 μeV5. In Fig. 1e, we effectively tune the injected electron spin polarization via the excitation laser polarization  as ‹Sz›0 ∝−

as ‹Sz›0 ∝− and we observe zero field DNP for an electron spin polarization as low as 10%. This average spin is low compared with the electron spin injected electrically in hybrid ferromagnet/GaAs devices40,41. In these systems, zero field DNP has not been clearly identified, in part due to permanent stray magnetic fields in the device54.

and we observe zero field DNP for an electron spin polarization as low as 10%. This average spin is low compared with the electron spin injected electrically in hybrid ferromagnet/GaAs devices40,41. In these systems, zero field DNP has not been clearly identified, in part due to permanent stray magnetic fields in the device54.

Knight field tuning

In the absence of strain (that is,  reduced by several orders of magnitude), DNP at zero magnetic field could be enabled by a strong, inhomogeneous Knight field, which acts as a spin diffusion barrier33,34. The time averaged Knight field of an electron in a state ψ(

reduced by several orders of magnitude), DNP at zero magnetic field could be enabled by a strong, inhomogeneous Knight field, which acts as a spin diffusion barrier33,34. The time averaged Knight field of an electron in a state ψ( ) acting on one specific nucleus j given by27:

) acting on one specific nucleus j given by27:

where ν0 is the two-atom unit cell volume,  is the position of nucleus j, Aj is the hyperfine interaction constant ≃50 μeV on average for Ga and As. gN and μN are the nuclear g-factor and magneton, respectively. The mean electron spin

is the position of nucleus j, Aj is the hyperfine interaction constant ≃50 μeV on average for Ga and As. gN and μN are the nuclear g-factor and magneton, respectively. The mean electron spin  averaged over the X+ lifetime is expressed in units of . 0≤Γt≤1 represents the fraction of time during which the dot is occupied by an electron; therefore, Γt increases with laser power until saturation underlining that the Knight field is zero in the absence of electrons. The time and spatially averaged Knight field determined in single dot spectroscopy can be written as:

averaged over the X+ lifetime is expressed in units of . 0≤Γt≤1 represents the fraction of time during which the dot is occupied by an electron; therefore, Γt increases with laser power until saturation underlining that the Knight field is zero in the absence of electrons. The time and spatially averaged Knight field determined in single dot spectroscopy can be written as:

where  (0)‹S› is the Knight field in the centre of the dot where the electron probability density is at a maximum. The form factor for a dot with harmonic confinement is Γf=

(0)‹S› is the Knight field in the centre of the dot where the electron probability density is at a maximum. The form factor for a dot with harmonic confinement is Γf= ≃0.35. For the case of electrons localized near donors—that is, a Coulomb potential—the form factor is about three times smaller as Γf≃

≃0.35. For the case of electrons localized near donors—that is, a Coulomb potential—the form factor is about three times smaller as Γf≃ ≃0.125. This is one of the reasons why the Knight fields reported here in dots are stronger than those reported in bulk GaAs for electrons localized on donors12,15,46 and are likely to be larger than the local field BL, thus stabilizing the nuclear spins, see Supplementary Methods. This would imply that it is possible to compensate the Knight field by a longitudinal magnetic field BZ in the mT range12,20, such that when ‹Be›QD=−BZ the nuclei experience a zero total field and that nuclear depolarization due to the local field BL becomes possible. One expects the global minimum of the measured DNP as a function of BZ to appear at this point and not at zero field.

≃0.125. This is one of the reasons why the Knight fields reported here in dots are stronger than those reported in bulk GaAs for electrons localized on donors12,15,46 and are likely to be larger than the local field BL, thus stabilizing the nuclear spins, see Supplementary Methods. This would imply that it is possible to compensate the Knight field by a longitudinal magnetic field BZ in the mT range12,20, such that when ‹Be›QD=−BZ the nuclei experience a zero total field and that nuclear depolarization due to the local field BL becomes possible. One expects the global minimum of the measured DNP as a function of BZ to appear at this point and not at zero field.

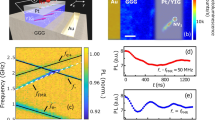

This is indeed what we find in the experiments, see Fig. 2a. When exciting the dot with a σ− polarized laser, the Overhauser shift passes through a minimum at BZ≈−10 mT. When changing the helicity of the light polarization, the minimum in absolute value is observed at BZ≈+10 mT, with intermediate values for elliptical polarization (circles in Fig. 2a). Electron spin relaxation in these small longitudinal applied fields is negligible. The Knight field depends on the average electron spin  , see equations 1 and 2. The amplitude and direction of the mean electron spin in the X+ are controlled by the polarization of the excitation laser. This allows for Knight field tuning55. The dependence of the applied field BZ at which the minimum Overhauser shift is observed as a function of injected mean electron spin (that is, laser polarization) is roughly linear in Fig. 2b. This is a strong indication that the Knight field compensation indeed determines the global minimum of the DNP as a function of BZ. With respect to the work on zero field DNP in strained InGaAs dots by Lai et al.20, the Knight field amplitudes reported here of up to

, see equations 1 and 2. The amplitude and direction of the mean electron spin in the X+ are controlled by the polarization of the excitation laser. This allows for Knight field tuning55. The dependence of the applied field BZ at which the minimum Overhauser shift is observed as a function of injected mean electron spin (that is, laser polarization) is roughly linear in Fig. 2b. This is a strong indication that the Knight field compensation indeed determines the global minimum of the DNP as a function of BZ. With respect to the work on zero field DNP in strained InGaAs dots by Lai et al.20, the Knight field amplitudes reported here of up to  =18 mT are one order of magnitude higher. The initial explanation of Lai et al.20 was based on the Knight field stabilization of zero field DNP; this interpretation has subsequently evolved as static nuclear quadrupole effects seem to be dominant in strained dots6,42.

=18 mT are one order of magnitude higher. The initial explanation of Lai et al.20 was based on the Knight field stabilization of zero field DNP; this interpretation has subsequently evolved as static nuclear quadrupole effects seem to be dominant in strained dots6,42.

(a) X+ Overhauser shift as a function of the applied field Bz. Circles (squares) for σ−(σ+) laser polarization, triangles for elliptically polarized laser excitation. The magnetic field Bz, for which this dip occurs, is a measure of the Knight field amplitude. Error bars are given by spectral precision. (b) Knight field amplitudes extracted by fitting Gaussians to data in a for three typical dots (X+ transitions for QDs five and 6B, X+ (solid squares) and X− (hollow diamond) transitions for QD B), demonstrating Knight field tuning. The data show a roughly linear dependence as Be∝‹S›∝(− /2), typical error bars due to precision of fitting procedure are indicated.

/2), typical error bars due to precision of fitting procedure are indicated.

Knight field inhomogeneity

The measured nuclear spin polarization—that is, the Overhauser shift—does not drop abruptly to zero in Fig. 2a. The Knight field experienced by each individual nucleus will depend on its position in the QD as the electron wavefunction density decreases away from the dot centre. Owing to this spatial inhomogeneity of the Knight field, the exact compensation by the external field occurs only for a fraction of the total number of nuclei in the dot. The other nuclei can still be dynamically polarized and therefore contribute to the remaining Overhauser shift.

An immediate consequence of the large spatial inhomogeneities of the Knight field is that, contrary to the general case of electrons localized on donors in bulk GaAs12, the concept of a nuclear spin temperature32 among the whole nuclear spin system is not applicable, as detailed in the Supplementary Methods. On the basis of our measurements (see Fig. 2), we estimate that the Knight field gradient between two lattice sites of the same nuclear species in a typical dot in our sample is about one order of magnitude larger than BL (except close to the dot centre and the edges where  |ψ(r)2| vanishes). As a result, the nuclear spin diffusion from the dot centre to the outer layers is expected to be suppressed and no global spin temperature can be established in the dot. We therefore assume that only nuclei located on ellipsoids with equal electron wavefunction density can thermalize among themselves, as indicated in Fig. 3g, so that no nuclear spin coherence appears (in the cw regime). As an important consequence, the average nuclear spin polarization in a given shell will be collinear with the total field experienced by the nuclei, as shown in the experiments in the next section, see Fig. 3h. It is important to underline that despite the apparent Knight field inhomogeneity, the Knight field Be stabilization of the nuclear spin system at zero field is very efficient and nuclear spin polarization >10% can be achieved, equivalent to Overhauser fields Bn of several hundred mT.

|ψ(r)2| vanishes). As a result, the nuclear spin diffusion from the dot centre to the outer layers is expected to be suppressed and no global spin temperature can be established in the dot. We therefore assume that only nuclei located on ellipsoids with equal electron wavefunction density can thermalize among themselves, as indicated in Fig. 3g, so that no nuclear spin coherence appears (in the cw regime). As an important consequence, the average nuclear spin polarization in a given shell will be collinear with the total field experienced by the nuclei, as shown in the experiments in the next section, see Fig. 3h. It is important to underline that despite the apparent Knight field inhomogeneity, the Knight field Be stabilization of the nuclear spin system at zero field is very efficient and nuclear spin polarization >10% can be achieved, equivalent to Overhauser fields Bn of several hundred mT.

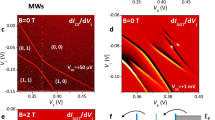

(a) Circular polarization degree of the PL emission as a function of the applied transverse magnetic field. Measurement (black circles) at low laser power (13 nW). Red line: Lorentzian fit. (b) Overhauser shift≃0—that is, there is no measurable DNP. (c) Same measurement as a but using higher laser excitation power (1.2 μW). (d) Strong Overhauser shift under high excitation power. (e) Calculated Hanle depolarization curve using equation 8—see Methods; (f) calculated longitudinal Overhauser field (black line) using equation 7 and transverse nuclear field (blue line). The compensation points where Bn,Y+BY=0 are marked by green circles. Red line: −BY. (g) Spin temperature within ellipsoids of equal electron probability density in the dot. (h) Effective and applied magnetic fields acting on electron and nuclear spin systems for one iso-Knight shell—see Methods.

Electron depolarization in transverse magnetic fields

In strained InGaAs dots in the presence of DNP, measurements of the electron depolarization in a transverse magnetic field (Voigt geometry) have led to the discovery of the anomalous Hanle effect25. In the presence of  of several hundred mT, the average nuclear polarization was not collinear with the strong applied field. Our aim is to verify whether the anomalous Hanle effect is also observed in strain-free dots or whether we can simply tilt the substantial Overhauser field generated at zero applied field in transverse fields in the mT range12.

of several hundred mT, the average nuclear polarization was not collinear with the strong applied field. Our aim is to verify whether the anomalous Hanle effect is also observed in strain-free dots or whether we can simply tilt the substantial Overhauser field generated at zero applied field in transverse fields in the mT range12.

For Hanle measurements, two situations have to be distinguished: with and without optical carrier spin pumping. In the absence of strong carrier spin pumping, and hence nuclear spin pumping, the only field acting on the spin is the applied magnetic field BY and a Lorentzian-shaped electron depolarization curve is observed1,47 as in Fig. 3a in the absence of DNP. This is achieved by lowering the laser power to such an extent that the Overhauser shift completely disappears (Fig. 3b). In Fig. 3a, we plot the circular polarization degree of the X+ PL as a function of the applied transverse magnetic field BY. Having determined the ge,⊥ factor beforehand56, fitting the Hanle curve with a Lorentzian allows to extract the electron spin lifetime  as ΔB=ħ/(ge,⊥|μB|

as ΔB=ħ/(ge,⊥|μB| )=43 mT. The obtained value of

)=43 mT. The obtained value of  =350 ps corresponds roughly to the radiative lifetime of the X+ in these structures28, which means that the electron spin is stable during the radiative lifetime.

=350 ps corresponds roughly to the radiative lifetime of the X+ in these structures28, which means that the electron spin is stable during the radiative lifetime.

In Fig. 3c, we repeated the same measurements but with a higher laser excitation power—that is, more efficient carrier and nuclear spin pumping. This results in a strong Knight field (as we have increased the filling factor Γt in equation 1) and strong DNP as confirmed by a substantial Overhauser shift (Fig. 3d). Several striking changes as compared with the standard Hanle effect without DNP emerge for the dots investigated: first, the Hanle curve is broadened. An increase in ΔB is expected if  decreases. This is plausible as the higher laser excitation power makes trapping of additional charges more likely; therefore, the effective time the X+ complex exists might be shortened as biexcitons are formed. Second, around zero field we observe a pronounced W-shape as can be verified in Fig. 3c.

decreases. This is plausible as the higher laser excitation power makes trapping of additional charges more likely; therefore, the effective time the X+ complex exists might be shortened as biexcitons are formed. Second, around zero field we observe a pronounced W-shape as can be verified in Fig. 3c.

Tilting the nuclear magnetization

These substantial changes of the electron polarization in applied transverse magnetic fields of only a few mT are surprising. We have developed a model (see Methods for a brief and the Supplementary Methods for a detailed description) based on the intricate interplay between the applied transverse field BY, the Knight field Be and the Overhauser field Bn that qualitatively reproduces the main features of the measured electron depolarization curve, compare Fig. 3c,e.

In the simulations, we use (i) the Knight field amplitude determined in the longitudinal magnetic field measurements in Fig. 2 and (ii) ΔB that we determine in the high transverse field part of the Hanle curve where nuclear effects are negligible. We are able to reproduce qualitatively the measured nuclear spin polarization (Fig. 3f) and electron polarization (Fig. 3e), namely the characteristic W-shape for |BY|≤20 mT. At low BY, the total field BT acting on the nuclei is determined by BY and Be. This introduces a tilt in the strong nuclear field Bn and hence a strong transverse field component Bn,Y that points in the opposite direction of BY, as indicated in Fig. 3h. The opposite sign of the transverse nuclear field Bn,Y with respect to the applied field BY can be directly verified in Fig. 3f. This configuration is responsible for the sudden drop in the electron polarization. As BY is increased and eventually fully compensates Bn,Y, the electron experiences a total field that is zero. In the experiments, we observe at this field a local maximum, as indicated in Fig. 3c. The applied field value BY, for which this maximum occurs, serves as an experimental determination of the transverse Overhauser field in the range of 50 mT as Bn,Y=−BY, as reproduced by our model that allows to determine the compensation points in Fig. 3f. The good overall agreement between the model and the experiments indicates that we included the key interactions in our model: Knight field Be, Overhauser field Bn and applied field BY and we can infer that  ≤1 mT has negligible influence. We can clearly see that the total nuclear field is collinear with the field experienced by the nuclei, in strong contrast to the findings in strained dots22,25,26. This allows us to finely tune the orientation (tilt) of the Overhauser field in the z–y plane by varying the laser polarization and BY.

≤1 mT has negligible influence. We can clearly see that the total nuclear field is collinear with the field experienced by the nuclei, in strong contrast to the findings in strained dots22,25,26. This allows us to finely tune the orientation (tilt) of the Overhauser field in the z–y plane by varying the laser polarization and BY.

At the compensation point Bn,Y=−BY, the experimentally observed polarization is lower than the calculated one as we have neglected the nuclear field fluctuations δBn in our theoretical analysis. When the electron is not protected by a strong external and/or internal magnetic field, it will precess around δBn, resulting in a decrease in the measured electron spin polarization6,57,58. As BY is further increased, we enter the regime of the standard Hanle effect as the electron precesses around a strong applied magnetic field in the absence of any substantial DNP. Comparison between data and theory allows us to extract the sign of the transverse electron g-factor, which is positive. In the opposite case, (ge,⊥<0) compensation between Bn,Y and BY is impossible as they would have the same sign, so that the striking W-shape would not appear.

Discussion

The combination of zero field DNP and the application of small transverse magnetic fields allow control of the longitudinal and transverse components of the magnetization of the mesoscopic nuclear spin ensemble in isolated (no wetting layer), strain-free GaAs dots. All deviations from the standard Hanle curve reported here occur for applied transverse fields in the tens of mT range. On one hand this indicates that both the Knight and the Overhauser fields are 1–2 orders of magnitude stronger than in the case of electrons localized at donors in bulk GaAs12. On the other hand, the effects reported here occur for external magnetic fields one order of magnitude smaller compared with the very anomalous Hanle effect reported for strained InGaAs dots25,26. Our measurements confirm that strain and the associated static nuclear quadrupole effects are at the origin of the intriguing observations in InGaAs dots.

The coupled electron to nuclear spin system shows highly nonlinear dynamics6 and should be investigated in the future under (quasi-)resonant pumping conditions in order to achieve an electron spin polarization >50%. This would allow to verify the exciting predictions of phase transitions of the mesoscopic nuclear spin ensemble59, which might be enhanced due to the negligible static nuclear quadrupole effects in the strain-free GaAs droplet dots investigated here. Another extension of this work is the investigation of spin diffusion between two GaAs droplet dots through the AlGaAs barrier60, in the presence61 or absence of a wetting layer30, a comparison that cannot be made in the SK dot systems. Zero field DNP reported here is also expected to occur during all-electrical manipulations of nuclear and electron spin polarization40,41, although it has not been reported yet.

Methods

Samples and experiments

The sample was grown by droplet epitaxy using a molecular beam epitaxy system30,44 on a GaAs(111)A substrate. The dots are grown on 100-nm thick Al0.3Ga0.7As barriers and are covered by 50 nm of the same material. In this model system, dots (typical height≃2–3 nm, radius≃15 nm) are truly isolated as they are not connected by a two-dimensional quantum well (wetting layer)30, contrary to SK dots and dots formed at quantum well interface fluctuations5,47. Single dot PL at 4 K is recorded with a home-built confocal microscope with a detection spot diameter of≃1 μm. The detected PL signal is dispersed by a spectrometer and detected by a Si-CCD camera. Optical excitation is achieved by pumping the AlGaAs barrier with a HeNe laser at 1.96 eV. Laser polarization control and PL polarization analysis are performed with Glan–Taylor polarizers and liquid crystal waveplates. The PL circular polarization degree is defined as ρ = , where Iσ+(Iσ−) is the σ+(σ−) polarized PL intensity. As we excite heavy and light hole transitions in the AlGaAs barrier, 100% laser polarization results in a maximum PL polarization ρmax=50% for the X+, corresponding to a maximum initial electron spin polarization of 50%. In our experiment, we find typically ρ≃40% for most dots at zero applied magnetic field. The PL emission energy is determined with a precision of 1 μeV from Gaussian fits to the spectra (signal to noise ratio 104, full-width at half-maximum≃40 μeV limited by spectrometer resolution). The spectral precision is calibrated in experiments with a Fabry–Perot interferometer with the resolution of 0.2 μeV23. Magnetic fields up to 9 T can be applied both parallel (Faraday geometry) and perpendicular (Voigt geometry) to the growth axis [111] that is also the angular momentum quantization axis and the light propagation axis.

, where Iσ+(Iσ−) is the σ+(σ−) polarized PL intensity. As we excite heavy and light hole transitions in the AlGaAs barrier, 100% laser polarization results in a maximum PL polarization ρmax=50% for the X+, corresponding to a maximum initial electron spin polarization of 50%. In our experiment, we find typically ρ≃40% for most dots at zero applied magnetic field. The PL emission energy is determined with a precision of 1 μeV from Gaussian fits to the spectra (signal to noise ratio 104, full-width at half-maximum≃40 μeV limited by spectrometer resolution). The spectral precision is calibrated in experiments with a Fabry–Perot interferometer with the resolution of 0.2 μeV23. Magnetic fields up to 9 T can be applied both parallel (Faraday geometry) and perpendicular (Voigt geometry) to the growth axis [111] that is also the angular momentum quantization axis and the light propagation axis.

Model for experiments in transverse magnetic fields

See Supplementary Methods for a more detailed description. We assume for simplicity, harmonic carrier confinement in the three spatial directions. We include in our model the possibility of a small tilt angle θ≤3° in the sample holder used for transverse magnetic fields (Voigt geometry). We define the following bases ={x,y,z}, where z is normal to the sample surface and y is in the plane (O,B,z); ′={x′,y′,z′}, where x′=x and y ′||B obtained by rotation of around axis Ox by an angle θ=(y,B);  ={X,Y,Z} where Y=y′ and Z||S obtained by rotation of

={X,Y,Z} where Y=y′ and Z||S obtained by rotation of  ′ around axis Oy′ by an angle φ=(z′,B). Here B is the total field experienced by the electron of average spin ‹S›. We neglect throughout our analysis the hyperfine coupling between nuclei and valence holes, which is about one order of magnitude weaker than that for electrons6. The initial, photogenerated electron spin can be written as:

′ around axis Oy′ by an angle φ=(z′,B). Here B is the total field experienced by the electron of average spin ‹S›. We neglect throughout our analysis the hyperfine coupling between nuclei and valence holes, which is about one order of magnitude weaker than that for electrons6. The initial, photogenerated electron spin can be written as:

The rotation angle φ given by the Bloch equations quantifies the precession of the electron in the total field B=BY+Bn,Y (see scheme in Fig. 3h) can be expressed as32:

where ΔB=/(ge,⊥|μB| ) and 1/

) and 1/ =1/τs+1/τ, where τ is the lifetime of the trion X+. The final results of the calculation are expressed in reduced magnetic field units βn,Y≡

=1/τs+1/τ, where τ is the lifetime of the trion X+. The final results of the calculation are expressed in reduced magnetic field units βn,Y≡ and βn,Z≡

and βn,Z≡ and the dimensionless Hanle width (without DNP), which is Δβ≡

and the dimensionless Hanle width (without DNP), which is Δβ≡ . We can calculate the nuclear field components as:

. We can calculate the nuclear field components as:

where

Here  is the polylogarithmic function,

is the polylogarithmic function,  is the average nuclear g-factor, NL is the number of nuclei in the dot and Q=5 for a GaAs dot6.

is the average nuclear g-factor, NL is the number of nuclei in the dot and Q=5 for a GaAs dot6.  is an average leakage factor taking into account all relevant nuclear spin relaxation mechanisms. Equation 5 is an implicit equation, since the complex variable Ξ is a function of βn,Y. The constant K represents the feedback coefficient of the nuclear magnetization of the QD on βn,Y itself. We obtain the longitudinal Overhauser field using βn,Y and βn,Z:

is an average leakage factor taking into account all relevant nuclear spin relaxation mechanisms. Equation 5 is an implicit equation, since the complex variable Ξ is a function of βn,Y. The constant K represents the feedback coefficient of the nuclear magnetization of the QD on βn,Y itself. We obtain the longitudinal Overhauser field using βn,Y and βn,Z:

which can be compared with the measurements, see Fig. 3d,f. Finally, we also obtain an expression for the circular polarization degree of the X+ emission:

Equation 8 reproduces the measured polarization qualitatively, compare Fig. 3c,e, using the the experimentally determined parameters  =18 mT, ge,⊥=0.78, δn=12 μeV and ΔB=80 mT. The following parameters have been adjusted within plausible bounds to reproduce closely the PL experiments: NL=40,000 (given by atomic force microscopy measurements),

=18 mT, ge,⊥=0.78, δn=12 μeV and ΔB=80 mT. The following parameters have been adjusted within plausible bounds to reproduce closely the PL experiments: NL=40,000 (given by atomic force microscopy measurements),  =0.22, θ=0.5°; the value of Γt=0.3 is determined by

=0.22, θ=0.5°; the value of Γt=0.3 is determined by  .

.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Sallen, G. et al. Nuclear magnetization in gallium arsenide quantum dots at zero magnetic field. Nat. Commun. 5:3268 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4268 (2014).

References

Meier, F. & Zakharchenya, B. Optical orientation. Modern Problems in Condensed Matter Sciences Vol. 8, North Holland (1984).

King, J. P., Li, Y., Meriles, C. A. & Reimer, J. A. Optically rewritable patterns of nuclear magnetization in gallium arsenide. Nat. Commun. 3, 918 (2012).

Kalevich, V. K., Korenev, V. L. & Fedorova, O. M. Optical polarization of nuclei in GaAs/AlGaAs quantum-well structures. JETP Lett. 52, 349–354 (1990).

Salis, G. et al. Optical manipulation of nuclear spin by a two-dimensional electron gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 2677–2680 (2001).

Gammon, D. et al. Nuclear spectroscopy in single quantum dots: nanoscopic raman scattering and nuclear magnetic resonance. Science 277, 85–88 (1997).

Urbaszek, B. et al. Nuclear spin physics in quantum dots: an optical investigation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 79–133 (2013).

Reimer, J. A. Nuclear hyperpolarization in solids and the prospects for nuclear spintronics. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 37, 3–12 (2010).

Kaur, G. & Denninger, G. Dynamic nuclear polarization in III-V semiconductors. Appl. Magn. Reson. 39, 185–204 (2010).

Machida, T., Yamazaki, T. & Komiyama, S. Local control of dynamic nuclear polarization in quantum hall devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 4178–4180 (2002).

Chen, Y. S. et al. Manipulation of nuclear spin dynamics in n-GaAs using an on-chip microcoil. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 016106 (2011).

Overhauser, A. W. Polarization of nuclei in metals. Phys. Rev. 92, 411–415 (1953).

Paget, D., Lampel, G., Sapoval, B. & Safarov, V. I. Low field electron-nuclear spin coupling in gallium arsenide under optical pumping conditions. Phys. Rev. B 15, 5780–5796 (1977).

Berkovits, V. L., Hermann, C., Lampel, G., Nakamura, A. & Safarov, V. I. Giant overhauser shift of conduction-electron spin resonance due to optical polarization of nuclei in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 18, 1767–1779 (1978).

Dyakonov, M. I., Perel, V. I., Berkovits, V. L. & Safarov, V. I. Optical effects due to polarization of nuclei in semiconductors. Sov. Phys. JETP 40, 950–955 (1975).

Giri, R. et al. Giant photoinduced faraday rotation due to the spin-polarized electron gas in an n-GaAs microcavity. Phys. Rev. B 85, 195313 (2012).

Chekhovich, E. A. et al. Structural analysis of strained quantum dots using nuclear magnetic resonance. Nat. Nanotech. 7, 646–650 (2012).

Bulutay, C. Quadrupolar spectra of nuclear spins in strained InGaAs quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 85, 115313 (2012).

Latta, C. et al. Confluence of resonant laser excitation and bidirectional quantum-dot nuclear-spin polarization. Nat. Phys. 5, 758–763 (2009).

Högele, A. et al. Dynamic nuclear spin polarization in the resonant laser excitation of an InGaAs quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 197403 (2012).

Lai, C. W., Maletinsky, P., Badolato, A. & Imamoglu, A. Knight-field-enabled nuclear spin polarization in single quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 167403 (2006).

Moskalenko, E. S., Larsson, L. A. & Holtz, P. O. Spin polarization of the neutral exciton in a single inas quantum dot at zero magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 80, 193413 (2009).

Dzhioev, R. I. & Korenev, V. L. Stabilization of the electron-nuclear spin orientation in quantum dots by the nuclear quadrupole interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 037401 (2007).

Belhadj, T. et al. Controlling the polarization eigenstate of a quantum dot exciton with light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 086601 (2009).

Oulton, R. et al. Subsecond spin relaxation times in quantum dots at zero applied magnetic field due to a strong electron-nuclear interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 107401 (2007).

Krebs, O. et al. Anomalous hanle effect due to optically created transverse overhauser field in single InAs/GaAs quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 056603 (2010).

Nilsson, J. et al. Voltage control of electron-nuclear spin correlation time in a single quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 88, 085306 (2013).

Dyakonov, M. Spin Physics in Semiconductor Nanostructures Vol. 157, Springer Series in Solid-State Science, Springer (2008).

Kuroda, T. et al. Symmetric quantum dots as efficient sources of highly entangled photons: violation of bell’s inequality without spectral and temporal filtering. Phys. Rev. B 88, 041306 (2013).

Stevenson, R. M. et al. Coherent entangled light generated by quantum dots in the presence of nuclear magnetic fields. Preprint at. http://arxiv.org/abs/1103.2969 (2011).

Mano, T. et al. Self-assembly of symmetric GaAs quantum dots on (111)a substrates: suppression of fine-structure splitting. Appl. Phys. Express 3, 065203 (2010).

Knight, W. D. Nuclear magnetic resonance shift in metals. Phys. Rev. 76, 1259–1260 (1949).

Abragam, A. Principles of Nuclear Magnetism Oxford University Press (1961).

Lu, J. et al. Nuclear spin-lattice relaxation in n-type insulating and metallic GaAs single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 74, 125208 (2006).

Ramanathan, C. Dynamic nuclear polarization and spin diffusion in nonconducting solids. Appl. Magn. Reson. 34, 409–421 (2008).

Kobayashi, T., Hitachi, K., Sasaki, S. & Muraki, K. Observation of hysteretic transport due to dynamic nuclear spin polarization in a GaAs lateral double quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 216802 (2011).

Petersen, G. et al. Large nuclear spin polarization in gate-defined quantum dots using a single-domain nanomagnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 177602 (2013).

Hanson, R., Kouwenhoven, L. P., Petta, J. R., Tarucha, S. & Vandersypen, L. M. K. Spins in few-electron quantum dots. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 1217–1265 (2007).

Bluhm, H. et al. Dephasing time of GaAs electron-spin qubits coupled to a nuclear bath exceeding 200 micro s. Nat. Phys. 7, 109–113 (2010).

Hermelin, S. et al. Electrons surfing on a sound wave: an experimental platform for quantum optics with flying electrons. Nature 447, 435–438 (2011).

Shiogai, J. et al. Dynamic nuclear spin polarization in an all-semiconductor spin injection device with (Ga,Mn)As/n-GaAs spin Esaki diode. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 212402 (2012).

Salis, G., Fuhrer, A. & Alvarado, S. F. Signatures of dynamically polarized nuclear spins in all-electrical lateral spin transport devices. Phys. Rev. B 80, 115332 (2009).

Maletinsky, P., Kroner, M. & Imamoglu, A. Breakdown of the nuclear-spin-temperature approach in quantum-dot demagnetization experiments. Nat. Phys. 5, 407–411 (2009).

Keizer, J. G. et al. Atomic scale analysis of self assembled GaAs/AlGaAs quantum dots grown by droplet epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 062101 (2010).

Sallen, G. et al. Dark-bright mixing of interband transitions in symmetric semiconductor quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 166604 (2011).

Paget, D., Amand, T. & Korb, J.-P. Light-induced nuclear quadrupolar relaxation in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 77, 245201 (2008).

Chen, Y. S., Reuter, D., Wieck, A. D. & Bacher, G. Dynamic nuclear spin resonance in n-GaAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 167601 (2011).

Bracker, A. S. et al. Optical pumping of the electronic and nuclear spin of single charge-tunable quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 047402 (2005).

Laurent, S. et al. Negative circular polarization as a general property of n-doped self-assembled InAsGaAs quantum dots under nonresonant optical excitation. Phys. Rev. B 73, 235302 (2006).

Cortez, S. et al. Optically driven spin memory in n-doped InAs/GaAs quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 207401 (2002).

Verbin, S. Y. et al. Dynamics of nuclear polarization in InGaAs quantum dots in a transverse magnetic field. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 114, 681–690 (2012).

Chekhovich, E. A. et al. Element-sensitive measurement of the hole nuclear spin interaction in quantum dots. Nat. Phys. 9, 74–78 (2013).

Fischer, J., Coish, W. A., Bulaev, D. V. & Loss, D. Spin decoherence of a heavy hole coupled to nuclear spins in a quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 78, 155329 (2008).

Eble, B. et al. Hole nuclear spin interaction in quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 146601 (2009).

Van Dorpe, P., Van Roy, W., De Boeck, J. & Borghs, G. Nuclear spin orientation by electrical spin injection in an AlGaAs/GaAs spin-polarized light-emitting diode. Phys. Rev. B 72, 035315 (2005).

Makhonin, M. N. et al. Optically tunable nuclear magnetic resonance in a single quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 82, 161309 (2010).

Durnev, M. V. et al. Magnetic field induced valence band mixing in [111] grown semiconductor quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 87, 085315 (2013).

Merkulov, I. A., Efros, A. L. & Rosen, M. Electron spin relaxation by nuclei in semiconductor quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 65, 205309 (2002).

Khaetskii, A. V., Loss, D. & Glazman, L. Electron spin decoherence in quantum dots due to interaction with nuclei. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 186802 (2002).

Kessler, E. M. et al. Dissipative phase transition in a central spin system. Phys. Rev. A 86, 012116 (2012).

Malinowski, A., Brand, M. A. & Harley, R. T. Nuclear effects in ultrafast quantum-well spin-dynamics. Physica E 10, 13–16 (2001).

Belhadj, T. et al. Optically monitored nuclear spin dynamics in individual GaAs quantum dots grown by droplet epitaxy. Phys. Rev. B 78, 205325 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially funded by the ERC Starting Grant No.306719, ITN SpinOptronics and ANR QUAMOS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K., T.M. and K.S. developed and grew the samples. T.A., X.M. and B.U. conceived the experiments. G.S., S.K., L.B. and B.U. carried out the experiments. O.K. and G.S. analysed the data. T.A. and D.P. developed the model. B.U., and X.M. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-3, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 304 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sallen, G., Kunz, S., Amand, T. et al. Nuclear magnetization in gallium arsenide quantum dots at zero magnetic field. Nat Commun 5, 3268 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4268

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4268

This article is cited by

-

Nuclear spin diffusion in the central spin system of a GaAs/AlGaAs quantum dot

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Droplet epitaxy of semiconductor nanostructures for quantum photonic devices

Nature Materials (2019)

-

Fabrication and Optical Properties of Strain-free Self-assembled Mesoscopic GaAs Structures

Nanoscale Research Letters (2017)

-

Manipulation of a Nuclear Spin by a Magnetic Domain Wall in a Quantum Hall Ferromagnet

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Quantum dot spin coherence governed by a strained nuclear environment

Nature Communications (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.