Abstract

The Poisson’s ratio is a fundamental measure of the elastic-deformation behaviour of materials. Although negative Poisson’s ratios are theoretically possible, they were believed to be rare in nature. In particular, while some studies have focused on finding or producing materials with a negative Poisson’s ratio in bulk form, there has been no such study for nanoscale materials. Here we provide numerical and theoretical evidence that negative Poisson’s ratios are found in several nanoscale metal plates under finite strains. Furthermore, under the same conditions of crystal orientation and loading direction, materials with a positive Poisson’s ratio in bulk form can display a negative Poisson’s ratio when the material’s thickness approaches the nanometer scale. We show that this behaviour originates from a unique surface effect that induces a finite compressive stress inside the nanoplates, and from a phase transformation that causes the Poisson’s ratio to depend strongly on the amount of stretch.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When stretched, materials with a negative Poisson’s ratio become thicker in the direction perpendicular to the original force1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Materials exhibiting such counterintuitive behaviour, known as auxetics, are of great interest not only because they are rare, but also because of their numerous potential applications in various fields, such as the design of fasteners12, prostheses13, pizeocomposites14,15, filters16, earphones17, seat cushions18,19 and superior dampers20. Materials with negative Poisson’s ratios have been extensively studied since Lakes1 reported a negative Poisson’s ratio in a reentrant foam structure. Reentrant foam structure is an example of ‘structural networks’2,3,4,5,21,22,23 that manifest a negative Poisson’s ratio, whereas their components at the molecular or microscale level have positive Poisson’s ratios. Among structural networks are molecular networks3, hierarchical structures4, composites5 and hinged structures22,23. Some materials exhibit auxetic properties as they are stretched or compressed in a proper direction6,7,8,9,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. For example, Baughman et al.7 reported that 69% of all cubic materials exhibit a negative Poisson’s ratio along the [ ]-direction when they are subjected to stretching along the [110]-direction. The origin of such single-crystal directional stretching had been previously explained by Milstein and Huang9. Negative Poisson’s ratios were also observed in some materials near phase transitions31,32,33,34,35. For example, Hirotsu31,32 reported that Poisson’s ratio of polymer gels becomes negative near the critical point of volume–phase transition. During the ferroelastic transition near the Curie point, barium titanate ceramic exhibits a negative Poisson’s ratio as well35. In addition, intermediate valent materials, such as samarium sulphide doped properly with lanthanum, yttrium or thulium, can exhibit negative Poisson’s ratios in all directions36,37. On the other hand, by using theoretical analysis and computer simulations, Wojciechowski38,39,40,41 showed that a negative Poisson’s ratio can be found in isotropic and thermodynamically stable two-dimensional models of materials, as well as in harmonic and tethered solids in any dimensionality under negative pressure42. Norris43 provided analytic expressions of the extreme values of Poisson’s ratio over all possible directions for cubic materials. Paszkiewicz and Wolski44 and Brańka et al.45,46 derived a general expression as a function of elastic constants for the anisotropic Poisson’s ratio and conditions for the classification of any cubic material as auxetics, directional auxetics or non-auxetics. Especially, rare-earth alloys being auxetic in all direction and a few metal alloys exhibiting extreme directional auxetic behaviours were reported together with hundreds of non-auxetic materials45. However, all known auxetic materials are bulk materials, and to our knowledge there has been no study to systematically search for negative Poisson’s ratio materials at the nanoscale.

]-direction when they are subjected to stretching along the [110]-direction. The origin of such single-crystal directional stretching had been previously explained by Milstein and Huang9. Negative Poisson’s ratios were also observed in some materials near phase transitions31,32,33,34,35. For example, Hirotsu31,32 reported that Poisson’s ratio of polymer gels becomes negative near the critical point of volume–phase transition. During the ferroelastic transition near the Curie point, barium titanate ceramic exhibits a negative Poisson’s ratio as well35. In addition, intermediate valent materials, such as samarium sulphide doped properly with lanthanum, yttrium or thulium, can exhibit negative Poisson’s ratios in all directions36,37. On the other hand, by using theoretical analysis and computer simulations, Wojciechowski38,39,40,41 showed that a negative Poisson’s ratio can be found in isotropic and thermodynamically stable two-dimensional models of materials, as well as in harmonic and tethered solids in any dimensionality under negative pressure42. Norris43 provided analytic expressions of the extreme values of Poisson’s ratio over all possible directions for cubic materials. Paszkiewicz and Wolski44 and Brańka et al.45,46 derived a general expression as a function of elastic constants for the anisotropic Poisson’s ratio and conditions for the classification of any cubic material as auxetics, directional auxetics or non-auxetics. Especially, rare-earth alloys being auxetic in all direction and a few metal alloys exhibiting extreme directional auxetic behaviours were reported together with hundreds of non-auxetic materials45. However, all known auxetic materials are bulk materials, and to our knowledge there has been no study to systematically search for negative Poisson’s ratio materials at the nanoscale.

By virtue of the enhancement of nanotechnology, numerous layered structures with a thickness of several atomic layers have been achieved for various applications, through experimental techniques such as atomic layer deposition, thermal evaporation, chemical vapour deposition and molecular beam epitaxy methods47,48,49. Therefore, a fundamental understanding of the elastic behaviour of nanoscale plate-shaped materials becomes more important. The effects of free surface on the mechanical properties of nanostructures like nanoparticles, nanowires and nanoplates at unstrained state were systematically discussed by Dingreville et al.50 They incorporated the surface free energy into the continuum theory of mechanics and obtained effective elastic constants of nanostructures. For example, the Poisson’s ratio of the nanowire increases whereas the biaxial Poisson’s ratio of the nanoplate decreases as the thickness of the nanowire or nanoplate decreases. All of Poisson’s ratios they studied were larger than 0.4 and thus they did not address negative Poisson’s ratios in nanostructures.

In this study, we show that negative Poisson’s ratio is a feature of several metal plates with the nanometer thickness under finite strain, contrasting to their bulk counterparts that exhibit positive Poisson’s ratios. For this, we investigate a phase transformation under a proper loading condition and a nanoscale surface effect. The phase transformation induced by the intrinsic instability of cubic materials provokes different amounts of deformation along the two lateral directions. In addition, the relaxation of free surface generates a large compressive stress as a function of thickness and results in changing the Poisson’s ratios of the nanoplates. We illustrate that the phase transformation and pronounced surface effect are two essential conditions for the auxetic behaviour of metal nanoplates.

Results

Negative Poisson’s ratio in Al (001) nanoplates

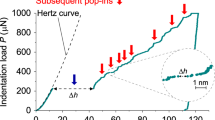

Using molecular statics (MS) calculations, we have investigated the Poisson’s ratio of a wide range of metal nanoplates, silicon nanoplates and different type of free surfaces. We first present our results for aluminium (Al) (001) nanoplates of different thicknesses under uniaxial loading. For convenience of notation, we assign here the x-, y- and z-directions to the [100]-, [010]- and [001]-directions, which correspond to the loading, in-plane lateral and thickness directions, respectively. As we apply uniaxial loading in the x-direction, there is only one non-zero stress component of Sxx, whereas the others are zero (Syy=Szz=Syz=Szx=Sxy=0). See Methods for details. Figure 1a shows the Poisson’s ratio of an Al (001) nanoplate with a thickness of 5a0 (where a0 is the lattice parameter of Al) as a function of applied stretch. Poisson’s ratio is strongly dependent on the amount of stretch and one component (νxy) increases while the other component (νxz) decreases until the strain reaches 5.7%. Along the y-direction, the contraction accelerates as the loading along the x-direction increases to finally reach a Poisson’s ratio of 2.8 at a strain of 5.7%, which signifies that the nanoplate shrinks about three times more along the in-plane lateral direction than it does in the loading direction. Along the z-direction, the Poisson’s ratio initially decreases monotonically and becomes negative at a strain of 3.2%, which signifies that the nanoplate contracts for a while (up to this strain value) and then expands along the thickness direction. It becomes auxetic and this Poisson’s ratio reaches −1.7 at a strain of 5.7%. The Poisson’s ratio becomes less strongly negative as the strain increases further, but it still remains negative even for very large strains (>9%).

(a) The Poisson’s ratio of an Al (001) nanoplate with a thickness of 5a0 (2.02 nm) under uniaxial tensile stress along the [100]-direction. (b) The Poisson’s ratio of Al (001) nanoplates with various thicknesses. There is branching for all cases, and the smoothing of the branching becomes more dominant as the thickness decreases.

To study the effect of nanoplate thickness on Poisson’s ratio, we examined Al (001) nanoplates with different thicknesses ranging from 3a0 to 60a0 (Fig. 1b). As the thickness varies, the Poisson’s ratio changes considerably as a function of the applied strain, and also the maximum and minimum Poisson’s ratios vary. For example, the maximum Poisson’s ratio reaches to 4.6 in the in-plane lateral direction and the minimum reaches to −3.2 in the thickness direction, for an Al (001) nanoplate with a thickness of 25a0. In addition, the onset strain at which the Poisson’s ratio in the thickness direction becomes negative changes as well; it increases as the thickness increases.

The behaviour of the Poisson’s ratio in bulk material is rather different. In bulk, the Poisson’s ratios in both the thickness and the in-plane lateral directions are equal and positive unlike nanoplates. They are nearly constant until the strain reaches 6%, and they change suddenly for a strain of 6–7% (Fig. 1b). The Poisson’s ratio converges to ~1.0 in the in-plane lateral direction and approximately −0.3 in the thickness direction for a large strain (>9%).

This branching of the Poisson’s ratios in bulk material is a manifestation of the phase transformation that arises as a result of the instability of materials. As Hill and Milstein51,52 predicted, a material becomes unstable when its elastic stiffness tensor loses its positive definiteness. The general condition for stability is  , where B is the elastic stiffness matrix in the Voigt notation. It is equivalent to the condition det[C]>0, where C is the elastic moduli matrix, in the case of uniaxial stretch in a principal direction for face-centered cubic (FCC) crystals. For a uniaxial loading in the [100]-direction, this condition reduces further to C22–C23>0. One can derive the deformation mode for this phase transformation by solving the eigenvalue problem of det[C–λI]=0. The corresponding deformation mode for uniaxial stretch in the [100]-direction is (δε1, δε2, δε3, δε4, δε5, δε6)=(0, 1,–1, 0, 0, 0) in the Voigt notation, which is a combination of a sudden expansion in one lateral direction and a sudden contraction in the other lateral direction with respect to the loading direction. It is noteworthy that phase transformation accompanies the formation of domains of different phases. Even in a complete transformation from one phase to another in a single crystal, the formation and propagation of domains can be observed. For example, in a molecular dynamics study, the transformation of a metal nanowire from an initial FCC structure to a final face-centered tetragonal structure begins from the formation of face-centered tetragonal domains and terminates by the annihilation of the FCC domain53. However, because we employed statics simulations, we have observed a homogeneous deformation as a result of the complete transformation rather than such domain formations in our MS and density functional theory (DFT) calculations, which is consistent with the previous statics studies54,55,56. Figure 2 shows the lattice parameters ay [010] and az [001] of bulk Al (100) under uniaxial tensile loading in the [100]-direction. As strain is applied to the structure, both lattice parameters reduce gradually and equally, then a sudden deformation happens right after strain 6.4%. In particular, the crystal symmetry of the bulk material under loading in the [100]-direction changes homogeneously from tetragonal to orthorhombic when the condition C22=C23 is satisfied, and this symmetry change explains the branching of the Poisson’s ratios and the occurrence of two different Poisson’s ratios for larger strain (>7%), as shown in Fig. 1b. We note that the branching of the Poisson’s ratio curves in Fig. 1b, for bulk material as well as for nanoplates, originates primarily from the phase transformation.

, where B is the elastic stiffness matrix in the Voigt notation. It is equivalent to the condition det[C]>0, where C is the elastic moduli matrix, in the case of uniaxial stretch in a principal direction for face-centered cubic (FCC) crystals. For a uniaxial loading in the [100]-direction, this condition reduces further to C22–C23>0. One can derive the deformation mode for this phase transformation by solving the eigenvalue problem of det[C–λI]=0. The corresponding deformation mode for uniaxial stretch in the [100]-direction is (δε1, δε2, δε3, δε4, δε5, δε6)=(0, 1,–1, 0, 0, 0) in the Voigt notation, which is a combination of a sudden expansion in one lateral direction and a sudden contraction in the other lateral direction with respect to the loading direction. It is noteworthy that phase transformation accompanies the formation of domains of different phases. Even in a complete transformation from one phase to another in a single crystal, the formation and propagation of domains can be observed. For example, in a molecular dynamics study, the transformation of a metal nanowire from an initial FCC structure to a final face-centered tetragonal structure begins from the formation of face-centered tetragonal domains and terminates by the annihilation of the FCC domain53. However, because we employed statics simulations, we have observed a homogeneous deformation as a result of the complete transformation rather than such domain formations in our MS and density functional theory (DFT) calculations, which is consistent with the previous statics studies54,55,56. Figure 2 shows the lattice parameters ay [010] and az [001] of bulk Al (100) under uniaxial tensile loading in the [100]-direction. As strain is applied to the structure, both lattice parameters reduce gradually and equally, then a sudden deformation happens right after strain 6.4%. In particular, the crystal symmetry of the bulk material under loading in the [100]-direction changes homogeneously from tetragonal to orthorhombic when the condition C22=C23 is satisfied, and this symmetry change explains the branching of the Poisson’s ratios and the occurrence of two different Poisson’s ratios for larger strain (>7%), as shown in Fig. 1b. We note that the branching of the Poisson’s ratio curves in Fig. 1b, for bulk material as well as for nanoplates, originates primarily from the phase transformation.

Change in the lattice parameters ay [010] and az [001] of bulk Al (100) under uniaxial tensile stress in the [100]-direction is shown. Both lattice parameters reduce equally as the stretch increases, and there is a sudden expansion in the y-direction and a sudden contraction in the z-direction at the critical strain of 6.4%. It is the deformation mode of bulk Al (001) that corresponds to the instability condition C22=C23. The crystal symmetry of the bulk material changes homogeneously from tetragonal to orthorhombic. Atomic positions before (solid dots) and after (open dots) the phase transformation are compared in inset.

Surface effects on Poisson’s ratio

As shown in Fig. 1b, the behaviour of nanoplates becomes closer to that of bulk material as the thickness increases, but diverges as the thickness decreases. On the basis of this observation, we conclude that the effect of the phase transformation becomes diluted when the thickness decreases. In other words, the surface effect of nanoplates becomes more dominant as the plates become thinner, resulting in a smoothing of the branching of the Poisson’s ratio. To examine this smoothing tendency in nanoplates relative to their bulk counterpart, we compare the stress distribution along the in-plane lateral direction and the thickness direction (Fig. 3a). Note that the total stresses in the two directions are zero as we apply uniaxial loading in the x-direction only. However, the stress inside the nanoplate in the y-direction is non-zero. The stress is very high and tensile on the first layer, and moderate and compressive on the next few layers from the (100) free surfaces. The stresses on the other layers are nearly constant and compressive, so as to compensate for the high tensile stress on the free surface. As a result, the stress field in the nanoplates along the in-plane lateral direction is not homogeneous, unlike in bulk. This is a unique characteristic of nanoplates and is ascribable to the so-called surface effect. The amount of compressive stress is determined by the tensile stress on the free surface of a nanoplate and the number of layers within it, because the total sum of the stresses on the entire nanoplate should be zero. Therefore, the amount of compressive stress increases as the thickness decreases (Fig. 3b), and it is inversely proportional (S~1 t−1) to the thickness of (001) nanoplates (Fig. 3c). Owing to the existence of the (001) free surface, the atoms inside nanoplates are under the tensile stress in the loading direction as well as under the compressive stress in the in-plane lateral direction for finite strains. As a result, the crystal symmetry of inside the Al (001) nanoplates is no longer tetragonal for finite strain. That is why the (001) nanoplates have two different Poisson’s ratio values, whereas the bulk counterpart maintains its tetragonal symmetry and has one single Poisson’s ratio value before the branching.

(a) Stress profile of a 2-nm-thick Al (001) nanoplate throughout its thickness at a strain of 1.0%. The stresses along the z-direction are zero for the layers inside the nanoplate, whereas the stresses along the y-direction are not. (b) Stress profiles of Al (001) nanoplates with different thicknesses at a strain of 1.0%. For all cases, stresses along the y-direction inside nanoplates are compressive, and they increase as the thickness decreases. (c) Relationship between compressive stress and the thickness of Al and Au (001) nanoplates. The compressive stress is inversely proportional to the thickness for all seven FCC metal (001) nanoplates we considered.

So far, we have discussed the existence of compressive stress in the in-plane direction as a consequence of the free surface in the nanoplates. The question that arises next is what effect does this compressive stress have on the Poisson’s ratios? To answer to this question, we intentionally assign compressive stresses in the in-plane lateral direction for bulk Al (001), and then repeat simulations. We apply periodic boundary conditions in all directions, thereby imposing no free surface. Under the assigned compressive stress (Syy) in the y-direction, we determine the deformation that makes the stress (Szz) in the z-direction zero. The results in terms of Poisson’s ratio are plotted in Fig. 4a for different values of Syy. Poisson’s ratio changes drastically as the stretch increases. Larger compressive stress induces larger changes in the Poisson’s ratios until they reach the extrema.

(a) Poisson’s ratio of bulk Al (001) for assigned compressive stresses along the y-direction. Larger compressive stress induces a larger change before reaching extreme points (<5.2%), and a smaller change beyond the extreme points (>5.2%). (b) Comparison of bulk Al (001) under the assigned compressive stress to natural Al (001) nanoplates. The same amount of the compressive stress induced inside each nanoplate is assigned to the corresponding bulk model for comparison.

In Fig. 4b, we show the results from two different material models: a bulk material and a nanoplate. The same amount of the compressive stress induced inside each nanoplate is assigned to the corresponding bulk model for comparison. Remarkably, the outputs of the two models are very similar to one another, indicating that the compressive stress in the in-plane lateral direction plays an important role in inducing a negative Poisson’s ratio as well as causing drastic changes in the Poisson’s ratio as a function of stretch. Different compressive stresses arising from different thicknesses are responsible for the different smoothing of the branching in the Poisson’s ratios.

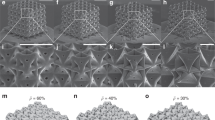

Poisson’s ratios in other cubic (001) nanoplates

In Fig. 5a, we compare the changes in Poisson’s ratio of FCC (001) nanoplates of seven metals such as Al, Ni, Cu, Pd, Ag, Pt and Au. Here we model all nanoplates with a uniform thickness of 5a0, and employ a different interatomic potential in the description of the interaction between metal atoms to exclude any artificial effect that may arise from the usage of a single potential. All FCC (001) nanoplates we considered to exhibit the same phenomena—that is, a negative Poisson’s ratio in the thickness direction, and a relatively large positive Poisson’s ratio in the in-plane lateral direction for finite strains. Although there are a little bit different values of Poisson’s ratio resulting from different induced-compressive stresses for employed elements, Poisson’s ratios in the thickness direction of all FCC (001) nanoplates turn to be negative at finite strain (>3.0%). The change in Poisson’s ratios is the largest in Cu nanoplate and the smallest in Au nanoplate.

(a) Poisson’s ratio of seven FCC (001) nanoplates each with a thickness of 5a0. All nanoplates exhibit the same behaviour: a negative Poisson’s ratio in the thickness direction and a relatively large positive Poisson’s ratio in the in-plane lateral direction at finite strain (>3.0%). (b) Comparison of DFT and MS results in the effect of compressive stress. Under assigned compressive stresses in the in-plane lateral (y-) direction, the changes in the lattice parameters of bulk Au (001) under loading in the x-direction are shown. (c) Poisson’s ratio of Fe (001) nanoplates with thickness of 3a0 and 5a0 as examples of BCC metals. Fe (001) nanoplate shows the same behaviour as FCC (001) nanoplates. (d) Poisson’s ratio of a Si (001) nanoplate with a thickness of 3a0. Si (001) nanoplates do not exhibit a negative Poisson’s ratio or a drastic change in the Poisson’s ratio, because the tensile stress on the free surface is too small to induce sufficient compressive stresses inside the Si (001) nanoplates.

To underline the generality of our finding and thus enhance the accuracy of our computations, we have performed DFT calculations as well. Because of expensive computational cost, we adopt DFT calculations to one bulk FCC material only. This time, we choose Au instead of Al to confirm the generality of our finding. The comparison of different methods is shown in Fig. 5b. When a uniaxial stress in the loading direction is applied (Syy=0), two results from DFT and MS models are in excellent agreement. The reductions of the lattice parameters with applied strain are the same in both models. In addition, the critical strain for the phase transformation is 8.8% in MS calculation and it is 8.9% in DFT calculation. When a finite compressive stress (Syy=0.5 GPa) is applied, the change in the lattice parameters in the DFT calculation is a little bit different from that in the MS calculation. However, a negative Poisson’s ratio in the thickness (z-) direction and a drastic change of Poisson’s ratio in the in-plane lateral (y-) direction at finite strains are clearly shown in both calculations.

In addition, we find that body-centered cubic (BCC) (001) metal nanoplates also exhibit the same phenomena as shown in Fig. 5c. As examples of BCC metals, we model iron (Fe) nanoplates with thickness of 3a0 and 5a0. The Poisson’s ratio in the thickness direction of the Fe (001) nanoplate with a thickness of 3a0 becomes negative at a strain of ~2.9%, whereas bulk Fe (001) never shows a negative Poisson’s ratio. It is noteworthy that for BCC metals a uniaxial compressive stress, rather than a tensile stress, must be applied to satisfy the condition C22=C23 for a phase transformation. Furthermore, FCC and BCC metal nanoplates show the same behaviour in spite of their contrasting atomic bonding characteristics and different amount of surface relaxation.

The change in Poisson’s ratio of silicon (Si) (001) nanoplates with strain is illustrated in Fig. 5d. The Poisson’s ratios of the Si (001) nanoplate with a thickness of 3a0 change a little bit as uniaxial loading applied, but they are always positive. Although bulk Si (001) has the same cubic symmetry as FCC and BCC metals, and thus undergoes a definite phase transformation under the uniaxial stretch in the [100]-direction, Si nanoplates do not exhibit the same drastic change in Poisson’s ratio.

The (001) free surface plays an important role in changing the Poisson’s ratios of FCC and BCC metals but it does not in those of Si. As shown in Fig. 5d, the Si nanoplate does not exhibit large changes in Poisson’s ratios even though Si (001) bulk has the same cubic symmetry with FCC and BCC metals. To explain this phenomenon, we compare stress profiles in the in-plane lateral direction inside Al, Fe and Si (001) nanoplates throughout their thickness in Fig. 6a. The internal compressive stresses induced by (001) free surfaces are different from one another. The compressive stress inside the Si (001) nanoplates is only ~70 MPa; that is, one order of magnitude lower than that of the inside FCC or BCC nanoplates. The tensile stress on Si (001) free surface is too small to induce a sufficient amount of compressive stresses inside the nanoplates. Consequently, Poisson’s ratios of even a thin Si (001) nanoplate do not change much from that of Si (001) bulk. It is noteworthy that Si (001) nanoplates also exhibit a negative Poisson’s ratio when we intentionally applied a large compressive stress (>1 GPa) in the in-plane lateral direction.

(a) Comparison of the stress profiles in the in-plane lateral direction inside Al, Fe and Si (001) nanoplates. The amount of compressive stress inside Si (001) nanoplates is much lower than that inside FCC or BCC metal nanoplates, and thus it cannot induce negative Poisson’s ratio or a drastic change in Poisson’s ratios. (b) Comparison of the stress profiles of Al nanoplates in the in-plane lateral direction with different free surfaces throughout their thickness. Although the (110) or (111) free surface exhibits high tensile stress on the first layer and thus induces finite compressive stresses in the in-plane lateral direction inside nanoplates, the Poisson’s ratios of the (110) or (111) nanoplates never become negative.

Comparison with other free surfaces

Now, we examine the Poisson’s ratios of metal nanoplates with different free surfaces such as (111) and (110). In Fig. 6b, we compare the stress profiles in the in-plane lateral direction inside Al (001), Al (111) and Al (110) nanoplates with 11 atomic layers in thickness. Like (001) surface, other free surfaces induce finite compressive stresses, and their values are approximately 780 MPa, 920 MPa and 2,140 MPa in order of (001), (111) and (110) nanoplates, respectively. However, as shown in Fig. 7, the nanoplate with (111) or (110) free surfaces never exhibits a negative Poisson’s ratio, even though the induced-compressive stresses cause large changes in the values of Poisson’s ratios. That is because there is no definite phase transformation in (111) or (110) nanoplates unlike (001) nanoplates. It is noteworthy that the nanoplates considered here are still in elastic range in spite of large stress and strain, because defect-free nanomaterials can support much larger elastic ranges of stress and strain as compared with their bulk counterparts57,58,59.

(a) Poisson’s ratio of a 2.79-nm-thick Al (111) nanoplate under uniaxial tensile stress in the [ ]-direction. The compressive stresses inside the nanoplates owing to the (111) free surface make a significant difference to the Poisson’s ratio values, but there is no negative Poisson’s ratio. (b) Poisson’s ratio of a 1.71-nm-thick Al (110) nanoplate under uniaxial tensile stress in the [001]-direction. Again, large compressive stress inside nanoplates owing to the (110) free surface causes different behaviours of the Poisson’s ratio, but it does not reach a negative value.

]-direction. The compressive stresses inside the nanoplates owing to the (111) free surface make a significant difference to the Poisson’s ratio values, but there is no negative Poisson’s ratio. (b) Poisson’s ratio of a 1.71-nm-thick Al (110) nanoplate under uniaxial tensile stress in the [001]-direction. Again, large compressive stress inside nanoplates owing to the (110) free surface causes different behaviours of the Poisson’s ratio, but it does not reach a negative value.

In addition, it is interesting that the compressive stress induced by the (001) free surface produces a negative Poisson’s ratio along the [001]-direction but it reduces a negative Poisson’s ratios along the [ ]-direction. It was reported that 69% of the cubic metals have negative Poisson's ratio along the [

]-direction. It was reported that 69% of the cubic metals have negative Poisson's ratio along the [ ]-direction, when they are stretched along the [110]-direction7,9. To underline the effect of (001) free surface, we calculate the Poisson's ratios of six FCC metal nanoplates and their bulk counterpart under the same conditions with the previous reports. All bulk FCC metals we considered show negative Poisson's ratios along the [

]-direction, when they are stretched along the [110]-direction7,9. To underline the effect of (001) free surface, we calculate the Poisson's ratios of six FCC metal nanoplates and their bulk counterpart under the same conditions with the previous reports. All bulk FCC metals we considered show negative Poisson's ratios along the [ ]-direction. However, these negative Poisson's ratios are reduced (Cu and Ni) or even removed (Au, Ag, Pt and Pd) when we introduce the (001) free surface at nanoscale, as shown in Table 1.

]-direction. However, these negative Poisson's ratios are reduced (Cu and Ni) or even removed (Au, Ag, Pt and Pd) when we introduce the (001) free surface at nanoscale, as shown in Table 1.

Discussion

We have shown that FCC (001) and BCC (001) nanoplates exhibit the negative Poisson’s ratio as they are stretched (FCC) or contracted (BCC). Although Si (001) bulk has the same cubic symmetry with FCC and BCC metals and thus has the definite phase transformation under the uniaxial stretch in the [100] direction, Si nanoplates do not show the drastic change in Poisson’s ratios because the surface effect is not sufficient. On the other hand, tensile stresses at surfaces of the (111) or (110) nanoplates are large enough to cause compressive stress inside the nanoplates, (111) or (110) nanoplates do not exhibit a negative Poisson’s ratio, because they do not have a definite phase transformation under uniaxial stretch. Therefore, both the proper direction of the loading relative to the lattice (needed to cause the Poisson’s ratio branching) and the large surface relaxation (needed to induce sufficient compressive stresses inside nanoplates for the smoothing) are two essential conditions for the creation of a negative Poisson’s ratio. Both of FCC and BCC (001) nanoplates inherently satisfy these conditions.

We have found that several metal nanoplates that have (001) free surface and nanoscale thickness exhibit a negative Poisson’s ratio along the thickness directions as they are under uniaxial loading in the [100] direction. As two primary origins for this unveiled behaviour of the metal nanoplates, we have discussed the finite compressive stresses inside the metal nanoplates inherently generated because of the (001) free surface and phase transformation induced by the intrinsic instability of cubic materials. This study reveals another interesting material property of nanostructures, negative Poisson’s ratio, and contributes to the database of auxetic materials that were believed to be uncommon in nature.

Methods

MS simulation

For metal (001) nanoplates, we designate the [100], [010] and [001] directions as x-, y- and z-directions, corresponding to the loading, in-plane lateral and thickness directions, respectively. We apply periodic boundary conditions to the x- and y-directions to model the nanoplates, and to all directions to model the bulk counterpart materials. The size of the nanoplates in the x- and y-directions is 10a0 × 10a0, where a0 is the lattice parameter of the considered element. We have confirmed that larger models give very similar results. We vary the thickness of the nanoplates from 3a0 to 60a0. The interaction between Al atoms is described by the interatomic potential developed by Liu et al.60, which has been shown to yield excellent results for surface energies and stacking-fault energies under various deformations. For other FCC metal atoms, we employ the interatomic potential proposed by Cai and Ye61 to exclude any artificial effect that may arise from the usage of a single potential. In the study of a BCC nanoplate, iron atoms are described by another empirical potential62. For Si (001) nanoplates, we use the Tersoff potential63.

Under the MS calculations, all models are fully relaxed to attain the equilibrium state before applying uniaxial loading, and then strain is applied in the x-direction with an increment of 0.1%. To achieve the uniaxial stress condition, the nanoplates are allowed to expand or contract in the y-direction to make the stress in the y-direction zero.

The definition of Poisson’s ratios under loading along the x-direction, for infinitesimal strain as well as finite strain, is given by

In the numerical evaluation, we use the central finite difference method with second-order accuracy to approximate the Poisson's ratio in equation (1). Then, the Poisson's ratios  of a plate at the strain

of a plate at the strain  can be obtained using

can be obtained using

DFT simulation

The local density approximation64 and ultra-soft pseudo-potential65 are used. We employ 13 × 13 × 13 Monkhorst-Pack66 meshes for sampling the Brillouin zone. All calculations are relaxed until forces on each ion become less than 0.01 eV Å−1 with a cutoff energy of 400 eV. We utilize the Cambridge Serial Total Energy Package (CASTEP)67 for DFT calculations.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Ho, D. T. et al. Negative Poisson’s ratios in metal nanoplates. Nat. Commun. 5:3255 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4255 (2014).

References

Lakes, R. Foam structures with a negative Poisson’s ratio. Science 235, 1038–1040 (1987).

Hall, L. J. et al. Sign change of Poisson’s ratio for carbon nanotube sheets. Science 320, 504–507 (2008).

Evans, K. E., Nkansah, M. A., Hutchinson, I. J. & Rogers, S. C. Molecular network design. Nature 353, 124–124 (1991).

Lakes, R. Materials with structural hierarchy. Nature 361, 511–515 (1993).

Milton, G. W. Composite materials with Poisson’s ratios close to -1. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 40, 1105–1137 (1992).

Keskar, N. R. & Chelikowsky, J. R. Negative Poisson ratios in crystalline SiO2 from first-principles calculations. Nature 358, 222–224 (1992).

Baughman, R. H., Shacklette, J. M., Zakhidov, A. A. & Stafström, S. Negative Poisson’s ratios as a common feature of cubic metals. Nature 392, 362–365 (1998).

Baughman, R. H. et al. Negative Poisson’s ratios for extreme states of matter. Science 288, 2018–2022 (2000).

Milstein, F. & Huang, K. Existence of a negative Poisson ratio in fcc crystals. Phys. Rev. B 19, 2030–2033 (1979).

Kimizuka, H., Kaburaki, H. & Kogure, Y. Mechanism for negative Poisson ratios over the α-β transition of cristobalite, SiO2: a molecular-dynamics study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 5548–5551 (2000).

Foerster, M. et al. The Poisson ratio in CoFe2O4 spinel thin films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 4344–4351 (2012).

Choi, J. B. & Lakes, R. S. Design of a fastener based on negative Poisson’s ratio foam. Cell Polym. 10, 205–212 (1991).

Scarpa, F. Auxetic materials for bioprostheses. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 25, 126–128 (2008).

Sigmund, O., Torquato, S. & Aksay, I. A. On the design of 1–3 piezocomposites using topology optimization. J. Mater. Res. 13, 1038–1048 (1998).

Gibiansky, L. V. & Torquato, S. On the use of homogenization theory to design optimal piezocomposites for hydrophone applications. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 45, 689–708 (1997).

Alderson, A. et al. An auxetic filter: a tunable filter displaying enhanced size selectivity or defouling properties. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 39, 654–665 (2000).

Jones, J. O. Cushioned earphones, US Patent 6,412,539 (filed 10 March 1999, and issued 2 July 2002).

Wang, Y.-C. & Lakes, R. Analytical parametric analysis of the contact problem of human buttocks and negative Poisson’s ratio foam cushions. Int. J. Solids Struct 39, 4825–4838 (2002).

Lowe, A. & Lakes, R. S. Negative Poisson’s ratio foam as seat cushion material. Cell Polym. 19, 157–167 (2000).

Scarpa, F., Ciffo, L. G. & Yates, J. R. Dynamic properties of high structural integrity auxetic open cell foam. Smart Mater. Struct. 13, 49–56 (2004).

Brandel, B. & Lakes, R. S. Negative Poisson’s ratio polyethylene foams. J. Mater. Sci. 36, 5885–5893 (2001).

Grima, J. N., Jackson, R., Alderson, A. & Evans, K. E. Do zeolites have negative Poisson’s ratios? Adv. Mater. 12, 1912–1918 (2000).

Ishibashi, I. & Iwata, M. A microscopic model of a negative Poisson's ratio in some crystals. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 69, 2702–2703 (2000).

Song, F., Zhou, J., Xu, X., Xu, Y. & Bai, Y. Effect of a negative Poisson ratio in the tension of ceramics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 245502 (2008).

Lethbridge, Z. A. D., Walton, R. I., Marmier, A. S. H., Smith, C. W. & Evans, K. E. Elastic anisotropy and extreme Poisson’s ratios in single crystals. Acta Mater. 58, 6444–6451 (2010).

Lubarda, V. A. & Meyers, M. A. On the negative Poisson ratio in monocrystalline zinc. Scr. Mater. 40, 975–977 (1999).

Boulanger, P. & Hayes, M. Poisson’s ratio for orthorhombic materials. J. Elast. 50, 87–89 (1998).

Rovati, M. Directions of auxeticity for monoclinic crystals. Scr. Mater. 51, 1087–1091 (2004).

Rovati, M. On the negative Poisson’s ratio of an orthorhombic alloy. Scr. Mater. 48, 235–240 (2003).

Aouni, N. & Wheeler, L. Auxeticity of calcite and aragonite polymorphs of CaCO3 and crystals of similar structure. Phys. Status Solidi B 245, 2454–2462 (2008).

Hirotsu, S. Elastic anomaly near the critical point of volume phase transition in polymer gels. Macromolecules 23, 903–905 (1990).

Hirotsu, S. Softening of bulk modulus and negative Poisson’s ratio near the volume phase transition of polymer gels. J. Chem. Phys. 94, 3949–3957 (1991).

Li, C., Hu, Z. & Li, Y. Poisson’s ratio in polymer gels near the phase-transition point. Phys. Rev. E 48, 603–606 (1993).

McKnight, R. E. A. et al. Grain size dependence of elastic anomalies accompanying the α–β phase transition in polycrystalline quartz. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 20, 075229 (2008).

Dong, L., Stone, D. S. & Lakes, R. S. Softening of bulk modulus and negative Poisson ratio in barium titanate ceramic near the Curie point. Philos. Mag. Lett. 90, 23–33 (2010).

Schärer, U. & Wachter, P. Negative elastic constants in intermediate valent SmxLa1-xS. Solid State Commun. 96, 497–501 (1995).

Schärer, U., Jung, A. & Wachter, P. Brillouin spectroscopy with surface acoustic waves on intermediate valent, doped SmS. Physica B 244, 148–153 (1998).

Wojciechowski, K. W. Constant thermodynamic tension Monte Carlo studies of elastic properties of a two-dimensional system of hard cyclic hexamers. Mol. Phys. 61, 1247–1258 (1987).

Wojciechowski, K. W. & Brańka, A. C. Negative Poisson ratio in a two-dimensional ‘isotropic’ solid. Phys. Rev. A 40, 7222–7225 (1989).

Wojciechowski, K. W. Two-dimensional isotropic system with a negative Poisson ratio. Phys. Lett. A 137, 60–64 (1989).

Wojciechowski, K. W. Non-chiral, molecular model of negative Poisson ratio in two dimensions. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 36, 11765–11778 (2003).

Wojciechowski, K. W. Negative Poisson ratios at negative pressures. Mol. Phys. Rep. 10, 129–136 (1995).

Norris, A. N. Poisson’s ratio in cubic materials. Proc. R. Soc. A 462, 3385–3405 (2006).

Paszkiewicz, T. & Wolski, S. Anisotropic properties of mechanical characteristics and auxeticity of cubic crystalline media. Phys. Status Solidi B 244, 966–977 (2007).

Brańka, A. C., Heyes, D. M. & Wojciechowski, K. W. Auxeticity of cubic materials. Phys. Status Solidi B 246, 2063–2071 (2009).

Brańka, A. C., Heyes, D. M. & Wojciechowski, K. W. Auxeticity of cubic materials under pressure. Phys. Status Solidi B 248, 96–104 (2011).

Osada, M. & Sasaki, T. Two-dimensional dielectric nanosheets: novel nanoelectronics from nanocrystal building blocks. Adv. Mater. 24, 210–228 (2012).

Qin, S., Kim, J., Niu, Q. & Shih, C.-K. Superconductivity at the two-dimensional limit. Science 324, 1314–1317 (2009).

Lim, B. S., Rahtu, A. & Gordon, R. G. Atomic layer deposition of transition metals. Nat. Mater. 2, 749–754 (2003).

Dingreville, R., Qu, J. & Cherkaoui, M. Surface free energy and its effect on the elastic behavior of nano-sized particles, wires and films. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 53, 1827–1854 (2005).

Hill, R. On the elasticity and stability of perfect crystals at finite strain. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 77, 225–240 (1975).

Hill, R. & Milstein, F. Principles of stability analysis of ideal crystals. Phys. Rev. B 15, 3087–3096 (1977).

Diao, J., Gall, K. & Dunn, M. L. Surface-stress-induced phase transformation in metal nanowires. Nat. Mater. 2, 656 (2003).

Milstein, F. & Farber, B. Theoretical fcc→bcc transition under [100] tensile loading. Phys. Rev. Lett. 44, 277–280 (1980).

Milstein, F., Marschall, J. & Fang, H. E. Theoretical bcc ⇆ fcc transitions in metals via bifurcations under uniaxial load. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 2977–2980 (1995).

Milstein, F., Zhao, J. & Maroudas, D. Atomic pattern formation at the onset of stress-induced elastic instability: fracture versus phase change. Phys. Rev. B 70, 184102 (2004).

Pashley, D. W. A study of the deformation and fracture of single-crystal gold films of high strength inside an electron microscope. Proc. R. Soc. A 255, 218–231 (1960).

Richter, G. et al. Ultrahigh strength single crystalline nanowhiskers grown by physical vapor deposition. Nano Lett. 9, 3048–3052 (2009).

Liddicoat, P. V. et al. Nanostructural hierarchy increases the strength of aluminium alloys. Nat. Commun. 1, 63 (2010).

Liu, X.-Y., Ercolessi, F. & Adams, J. B. Aluminium interatomic potential from density functional theory calculations with improved stacking fault energy. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 12, 665 (2004).

Cai, J. & Ye, Y. Y. Simple analytical embedded-atom-potential model including a long-range force for fcc metals and their alloys. Phys. Rev. B 54, 8398–8410 (1996).

Ackland, G. J., Bacon, D. J., Calder, A. F. & Harry, T. Computer simulation of point defect properties in dilute Fe-Cu alloy using a many-body interatomic potential. Philos. Mag. A 75, 713–732 (1997).

Tersoff, J. New empirical approach for the structure and energy of covalent systems. Phys. Rev. B 37, 6991–7000 (1988).

Ceperley, D. M. & Alder, B. J. Ground state of the electron gas by a stochastic method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 566–569 (1980).

Vanderbilt, D. Soft self-consistent pseudopotentials in a generalized eigenvalue formalism. Phys. Rev. B 41, 7892–7895 (1990).

Schlitt, D. W. Thermodynamics of the curvature of the Hc2-VS-T boundary in anisotropic superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 13, 4188–4191 (1976).

Payne, M. C., Teter, M. P., Allan, D. C., Arias, T. A. & Joannopoulos, J. D. Iterative minimization techniques for ab initio total-energy calculations: molecular dynamics and conjugate gradients. Rev. Mod. Phys. 64, 1045–1097 (1992).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support from Research Fund of the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST; grant nos. 1.090053.01, 1.130012.01) and from the Basic and Mid-Career Researcher Support Programs through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (MSIP; grant nos. 2012-0003369, 2011-0029212). We also thank the PLSI supercomputing resources of the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information (KISTI) and the UNIST Supercomputing Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y.K. designed and supervised the research; D.T.H. and S.-D.P. performed all of the calculations and analyses; S.-Y.K., K.P. and S.Y.K. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript; all authors have discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ho, D., Park, SD., Kwon, SY. et al. Negative Poisson’s ratios in metal nanoplates. Nat Commun 5, 3255 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4255

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4255

This article is cited by

-

Topological analysis and molecular modelling of liquid crystalline p-azoxyanisole and azobenzene compounds

Pramana (2023)

-

K-nanomechanics: advancements and applications of atomistic simulations in the Korean solid mechanics community

JMST Advances (2023)

-

Bending of a nanoplate with strain-dependent surface stress containing two collinear through cracks

Meccanica (2022)

-

Negative Poisson’s ratio in two-dimensional honeycomb structures

npj Computational Materials (2020)

-

Extreme negative mechanical phenomena in the zinc and cadmium anhydrous metal oxalates and lead oxalate dihydrate

Journal of Materials Science (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.