Abstract

In recent decades, the susceptibility to degradation in both ambient and aqueous environments has prevented organic electronics from gaining rapid traction for sensing applications. Here we report an organic field-effect transistor sensor that overcomes this barrier using a solution-processable isoindigo-based polymer semiconductor. More importantly, these organic field-effect transistor sensors are stable in both freshwater and seawater environments over extended periods of time. The organic field-effect transistor sensors are further capable of selectively sensing heavy-metal ions in seawater. This discovery has potential for inexpensive, ink-jet printed, and large-scale environmental monitoring devices that can be deployed in areas once thought of as beyond the scope of organic materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of field-effect transistors (FETs) for portable, label-free sensing applications in the field of healthcare and environmental monitoring has received great attention in recent decades1,2,3,4. Such devices allow for the transduction and conversion of a (bio-)chemical interaction into an electrical signal, providing compatibility with digital read-out methods. The sensing principle is based on the interaction or absorption of a charged species, for example, an ion5 or a DNA oligonucleotide6, with the interface of the FET. Hereby, the surface potential is changed, which affects the current that flows in the conductive channel of the FET via the field effect. To allow for selective detection of a particular species, the FET’s surface is chemically functionalized with specific binding groups3. The identification is then achieved by measuring the change in current, allowing for an electrical ‘fingerprint.’ Apart from the successful demonstration of FETs for the detection of DNA7,8, proteins9 or small molecules10,11, heavy-metal ion detection has also been investigated12,13 for monitoring water waste, coastal zone pollution and marine environment changes14. To provide reliable diagnostic tools for real-life applications, multifunctionalized sensors are essential15. Therefore, the goal is to fabricate large-scale sensing arrays with differently functionalized sensors. Silicon16, nanowires3, carbon nanotubes17 and (more recently) graphene18 have been explored as potential semiconducting materials for sensing applications. In addition, FETs built from organic materials (OFETs) have also become a focus of intense research19,20,21,22,23. In these devices, an organic small molecule or a polymer is used as the active semiconductor material. One important advantage of OFETs is their potential for low-cost, low-temperature, large-scale fabrication, which is made possible by facile solution and printing processability. OFET sensors have been demonstrated under ambient conditions for the detection of gases and vapours24, and have also recently been used for the detection of pressure25. Nevertheless, for the reliable detection of a biochemical reaction or the monitoring of water waste or the marine environment, a stable performance in an aqueous media is necessary. The instability of organic semiconductors in the presence of water in conjunction with high operating voltages for OFETs has previously led to nearly instantaneous device degradation during operation, limiting the use of OFETs as reliable and reproducible biochemical sensors in an aqueous environment26,27. To overcome this problem, an alternative route has been demonstrated in which the OFET sensor is exposed to a solution and dried before the measurement28,29. However, this method prevents real-time sensing capabilities. Further, a passivating (bi-) layer structure has been proposed30. This geometry, however, prevents a direct interaction of the aqueous media with the organic semiconductor. To this extent, only two organic materials have proven their stability in direct contact with an aqueous media. Roberts et al.19 were the first to demonstrate the stable performance of a small molecule, (5,5′-bis-(7-dodecyl-9H-fluoren-2-yl)-2,2′-bithiophene, known as DDFTTF, as a promising material for OFETs sensors. The insolubility of this molecule requires that it is deposited via thermal evaporation and is therefore not compatible with low-cost solution-processing techniques. Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) poly(styrenesulfonate), also known as PEDOT:PSS, has also been demonstrated as a stable organic material in aqueous environments31,32. However, this material is a conductive polymer rather than a semiconductor, and the current in a PEDOT:PSS sensor is modulated by electrochemical doping or de-doping, which limits its capabilities and performance21.

Herein we report and compare the use of a high-performance polymer semiconductor in an organic polymer-based FET sensor that overcomes the issue of water instability and is easily processable33. The presented OFET sensor is fully compatible with flexible substrates and is highly stable over extended periods of time. Furthermore, we demonstrate highly stable performance in a seawater environment. We demonstrate that our OFET can serve as a chemical sensor to monitor salinity changes and even be programmed for the selective detection of important analytes, such as heavy-metal ions in a marine environment. Our findings may be used to develop new types of OFET-based (bio-) chemical diagnostic tools, and lead to new design concepts in marine environments, a field that still lacks compact, stable sensor units.

Results

Electrical characterization under ambient conditions

To achieve the full potential offered by OFETs, a semiconductor that is compatible with solution-processing techniques is required. We recently reported a high mobility polyisoindigo-based polymer with siloxane-containing solubilizing chains33 (PII2T-Si) that can be spin coated from solution to form the channel of an OFET. Here we use this material to fabricate a polymer OFET sensor with outstandingly stable, long-term performance in aqueous environments, including deionized (DI) and seawater samples. Figure 1a shows the bottom-contact device structure used in this work. PII2T-Si is spin casted from a chloroform solution onto a pretreated silicon wafer with a 300-nm SiO2 dielectric layer. Before spin casting, gold electrodes were evaporated using shadow masks (channel dimensions width (w)=4,000 μm and length (l)=50 μm, Fig. 1a). The optimized fabrication protocol (see Methods section) results in a smooth, homogenous surface morphology (Fig. 1b). The PII2T-Si polymer’s compatibility with solution-processing techniques and low-temperature fabrication requirements lend themselves to the use of flexible substrates (Fig. 1c). The fabrication resulted in a high device yield of ~83%; of the 35 fabricated OFETs, 6 did not demonstrate transistor characteristics. Figure 2a shows the typical electrical characteristics of the OFETs under ambient conditions. A source-meter was used to apply a source-drain voltage (Vsd) to the electrodes and measure the resulting source-drain current (Isd). A back-gate voltage (Vbg) was applied to the silicon substrate (inset Fig. 2a). By sweeping Vbg at a constant Vsd, the transfer characteristics, Isd(Vbg) are obtained. The OFET’s transfer characteristics exhibit clear p-type behaviour with an on/off ratio of ~102 over the applied Vbg range (<6 V), consistent with our previously published results (Fig. 2a)33. The lower on/off ratio is due to the low gate voltage applied to the thick dielectric layer (Supplementary Fig. S1). However, the thick dielectric reduces the leakage current to the back gate, which is advantageous for underwater operation. Only a small hysteresis is visible and the electrical performance remains stable over multiple gate sweeps (Supplementary Fig. S2). The square root of the Isd(Vbg) curve is plotted on the right axis (Fig. 2, dashed red lines). The output characteristics, Isd(Vsd), are shown in Fig. 2b. Again, a clear p-channel FET behaviour is observed. Notably, the device performance does not degrade although our OFETs are stored under ambient conditions for months, which greatly simplifies device handling (Supplementary Fig. S2) and makes them highly amenable for practical, low-cost and novel applications.

(a) Device configuration using a bottom-contact structure. The PII2T-Si is spin coated on a silicon wafer with a SiO2 dielectric layer and previously evaporated gold electrodes of channel width (w) and length (l) (not to scale). (b) Surface morphology of the fabricated OFET measured with an atomic force microscope operated in tapping mode. Scale bar, 1 μm. (c) Optical image of a fabricated OFET on flexible substrate with a PDMS flow cell. Flow direction of the liquid is indicated by the black arrows. Scale bar, 1 cm.

(a) Transfer characteristics (source-drain current, Isd, versus back-gate voltage, Vbg) in ambient. Isd is plotted on a semi-logarithmic scale (left axis, black dots) and a constant source-drain voltage (Vsd) of −1 V is applied. The dimensions of the Au source-drain electrodes are length=50 μm and width=4,000 μm. Arrows indicate the gate sweep direction. Only a small hysteresis is observed. The right axis shows the square root plot of Isd (red-dashed lines). The inset shows the schematics of the measurement set-up. (b) Output plots (Isd versus source-drain voltage, Vsd) for different fixed Vbg in ambient. (c) Transfer characteristics measured in DI water. For this purpose, a PDMS flow cell was mounted on top of the OFET. The polymer OFET shows a slightly higher hysteresis under aqueous operating conditions. (d) Output characteristics for various fixed Vbg measured in DI water. (e) Transfer characteristics of the OFET in 10 μM NaCl solution using a liquid gate. For this purpose, a flow-through Ag/AgCl reference electrode was placed in close vicinity to the PDMS flow cell and in-line with the tubing. Isd current was recorded while sweeping the liquid-gate potential (Vlg) applied to the reference electrode at a constant Vsd (−0.6 V). A much smaller hysteresis and an on/off ratio over ~103 was observed over a small Vlg range (<0.5 V). The inset shows the schematics of the measurement set-up. (f) Output characteristics for various fixed Vlg.

Electrical characterization under aqueous conditions

Driven by its excellent stability under ambient conditions, we next studied the electrical performance of our OFET under aqueous environments, a feature that is critical for biosensing applications. A polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) flow cell was mounted directly on top of the fabricated devices (Fig. 1c), and a HPLC pump and automatic valve were used to deliver aqueous solutions. The bottom-contact electrodes were encapsulated by the polymer, which is an important key device feature we found necessary for preventing leakage currents that would otherwise flow between the electrodes in aqueous environments34. Figure 2c, d show the electrical characteristics (transfer and output plots, respectively) of the OFET in DI water. Surprisingly, we observed similar device performance to that observed under ambient conditions, with minimal increase in the device’s off-current. The on/off ratio remained ~102, while the square-root values of Isd were nearly unchanged. The increased hysteresis in Fig. 2c may be attributed to traps inside the polymer caused by ions, which diffuse into the film or penetrate the polymer through cracks in the thin film (Supplementary Fig. S3)27,35. The average electrical figures of merit were calculated over four different devices (threshold voltage (Vth)~−1.62±1.25 V, mobility (μ) ~0.035±0.02 cm2 Vs−1 and on/off ratio >130, Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Note 1). To study the organic semiconductor/liquid environment interface, we also performed liquid-gating measurements36 of our OFET devices by using a reference electrode to apply a potential to the liquid (Vlg) (inset Fig. 2e). A flow-through Ag/AgCl reference electrode was inserted in-line with the tubing near the flow cell (Supplementary Fig. S4) and a 10-μM NaCl solution was used as conductive electrolyte. Figure 2e shows the transfer characteristics of the OFET while sweeping Vlg. Remarkably, an on/off ratio >103 was achieved within a small Vlg range (0.5 V). The reduced operating voltage required to reach the saturation regime can be explained by the direct coupling of the liquid gate to the conductive channel34,37. The gating mechanism originates from an electrical double layer (Helmholtz layer), which is formed at the semiconductor/electrolyte interface. This layer accounts for the very high-gate capacitance, which is in the order of μF cm−2 (ref. 38). The hysteresis is less pronounced in a higher ionic solution (Fig. 2c versus e) than that in DI water. This confirms that a higher ionic concentration leads to a faster Helmholtz layer formation and a faster polarization time. As a direct consequence of this intimate coupling, less potential needs to be applied to induce charge carriers in the conductive channel, visible also by the increase of the square-root characteristics (dashed red lines, Fig. 2e). This behaviour indicates that the conductive channel is instead formed at the OFET’s surface (Supplementary Fig. S3)39. The average electrical figures of merit for the liquid-gate configuration were calculated over four different devices in DI water (Vth~−0.73 V ±0.07 V, μ~0.004±0.003 cm2 Vs−1 and on/off ratio >650) and in 10 μM NaCl (Vth~−0.72±0.02 V, μ~0.001±0.0008, cm2 Vs−1 and on/off ratio >150, Supplementary Table S1). The mobility in the liquid-gated configuration is found to be lower than that in the back-gated configuration. A similar finding has been previously reported for electrolyte-gated OFETs36, and can be explained by the increased gate dielectric capacitance (in this case, the electrical double layer), which tends to compress charge carrier distribution at the electrolyte/OFET interface. Hence, the charge transport is more sensitive to surface roughness and interface defects in the liquid-gated sample. The excellent performance of the OFETs is further supported by the output characteristics shown in Fig. 2e. Isd reaches saturation for small Vsd and Vlg (~mV range), an important feature for low-voltage (<1 V) applications19,36.

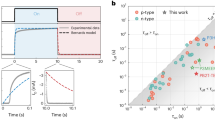

Long-term stability in deionized aqueous environment

Stable performance is an essential requirement of any sensor to provide reliable readings. An important factor for the successful implementation of OFETs as reliable biochemical sensors is their long-term stability in aqueous media. In this context, we explored the capability of our PII2T-Si polymer to survive for an extended time period in an aqueous environment by filling a PDMS cell with DI water and sealing it to prevent evaporation of the liquid. The device was measured periodically under the same conditions (Supplementary Fig. S5). Figure 3a shows a representative long-term transfer characteristic plot. Notably, almost no degradation of the OFET performance was observed for over the 17-day period that the OFET was stored under DI water. The stable on/off ratio (~103) and unchanging hysteresis indicate the outstanding stability of the PII2T-Si polymer. To quantify the stability of the device, the average threshold voltage (Vth,avg) was extracted and plotted for each measurement by taking the average value of the left slope (Vth,l) and the right slope (Vth,r; dashed black lines in Fig. 3a). Vth,avg remains surprisingly stable with only a small shift of ΔVth,avg~20 mV per day (inset Fig. 3a). We stress that, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time a polymer OFET shows exceptionally high electronic performance with long-term stability in an aqueous environment. Commonly used semiconducting organic polymers, such as poly(3-hexylthiophene) and poly(2,5-bis(3-hexadecylthiophen-2-yl)thieno[3,2-b]thiophene), degraded quickly and changed their performance on contact with humidity or aqueous liquids (Supplementary Fig. S6)40,41. We also compared the stability of PII2T-Si to a reference polymer (PII2T-ref) with the same polymer backbone and a similar surface morphology (Supplementary Figs S7 and S8), but a branched side chain that resulted in a larger π–π stacking distance (3.76 Å)33. PII2T-ref lost its transistor performance when brought into contact with either water or seawater (Supplementary Fig. S7). To better understand the reason behind the stability of our PII2T-Si polymer, we studied two additional polymeric semiconductors, poly(2,5-bis(2-octyldodecyl)-3,6-di(thiophen-2-yl)pyrrolo[3,4-c]pyrrole-1,4(2H,5H)-dione-co-thieno[3,2-b]thiophene), (PDPPTT) and poly(1,1′-bis(4-decyltetradecyl)-[3,3′-biindolinylidene]-2,2′-dione-co-2,2′-bithiophene), (PIID2T-C3), which possess similar energy levels and short π–π stacking distances (<3.6 Å) as the siloxane polymer while having similar alkyl sidechains as the PII2T-ref polymer. These two polymers have been reported to be highly stable in air42,43. Recently, it has been shown that a small π–π stacking may be the reason for air stability44. In our studies, we found that this argument may be valid for stability in liquid environments as well. Similar to our PII2T-Si polymer, OFETs fabricated from the PDPPTT and PIID2T-C3 polymers were also stable in aqueous environments. This is in contrast to the PII2T-ref polymer, which has a higher π–π stacking (3.76 Å), and was not stable in an aqueous environment. In addition, we found that the thickness of the polymer layer might also be responsible for the stability in aqueous environments (Supplementary Figs S9–S11; Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Note 2). While thicker polymer layers with short π–π stacking distance (in our case ~30 nm) were stable in both DI water and seawater samples, we found that thinner layers were not stable. However, for PII2T-ref polymer, even a thick layer of 130 nm was not stable. Further investigations are needed to better understand the myriad of possible factors contributing to the water stability of these polymers but are beyond the scope of this manuscript.

(a) Source-drain current (Isd) versus back-gate voltage (Vbg) measured over multiple days while stored continuously in DI water. Black arrows indicate gate sweep directions. Channel width (w)/length (l) ratio is 320. A small, unchanging hysteresis is visible. To extract the average threshold voltage (Vth,avg) shift shown in the inset, threshold voltages for the left (Vth,l) and right (Vth,r) slope were obtained by linear fit (dashed lines, guide to the eye) and Vth,avg was calculated by taking their average. Error bars represent the standard deviation. (b) Time-resolved measurement of Isd at a fixed working point (constant Vsd and Vbg) with w/l=80. The aqueous phase is cycled between DI water and seawater, with the pump set to a speed of 1 ml min−1. After the flow cell volume is fully replaced, the system reaches equilibrium and Isd plateaus (dashed red lines). The OFET demonstrated repeatable cycling between DI and seawater samples. (c) Isd versus Vbg of the same device shown in a measured over several weeks while stored in seawater. No degradation of the performance is visible. Extracted Vth,avg shifts are almost constant (inset). Error bars represent the standard deviation. (d) Time-resolved response of Isd to cycled increases in salinity (DI water, 0.01 × seawater, 0.1 × seawater, and seawater) for the same device shown in b. The working point was set to Vsd=−1 V and Vbg=−0.9 V. The pump was set to a speed of 1 ml min−1. After the solution in the flow cell was fully replaced, the pump was switched off. Isd reached repeatable, stable plateaus (indicated by the red-dashed lines).

Electronic performance and long-term stability in seawater

An important application of water-stable OFET sensors is environmental monitoring45. As a result of salinity changes and increased pollution in coastal zones due to a growing population and industrial pressure, there is a need for cheap, selective, lab-on-a-chip-type devices with in situ-monitoring capabilities. However, these sensors are far from being realized14 as corrosion, caused by the high salinity of seawater (~3–4%) and biofouling46 destroy device performance. We investigated the potential of our polymer OFETs in the liquid- and back-gate configurations to operate in seawater over a long period of time. Seawater has a high salinity (~600 mM) and contains more dissolved ions than any type of freshwater and is therefore an extremely harsh aqueous environment47. The most abundant dissolved ions are sodium, chloride, magnesium, sulphate and calcium. In addition. seawater also contains a high concentration and diversity of microorganism such as microbes and bacteria. The demonstration of stable operation and selective sensing in the harsh marine environment would lay the foundation for further development of these flexible low-cost devices for various applications. Figure 3b shows the response of Isd measured as a function of time at a fixed working point (constant Vsd and Vbg) while alternating between DI water and seawater collected from the Pacific Ocean. Exposing the OFET to seawater increases Isd by a factor of ~3 relative to DI water. Notably, the polymer OFET maintains excellent performance in both types of aqueous environments, demonstrating exceptionally high stability by achieving stable current plateaus (dashed red lines, Fig. 3b). We further analysed the performance of our OFET devices in both gate configurations. We found that for the liquid-gate configuration the leakage current between the liquid-gate electrode and the source-drain electrode (Igs) increases with each gate sweep (Supplementary Fig. S12). This finding can be explained by the fact that the conducting channel in the liquid-gate configuration is formed at the OFET/electrolyte interface (Supplementary Fig. S3). As conducting ions are present in the electrolyte and no passivation layer is present to protect the OFET, a parasitic leakage current flows from the source-drain electrode to the conducting channel and into the liquid-gate electrode (Supplementary Fig. S13a). From a voltammogram cycle of DI water and seawater, we can clearly identify a smaller stability range for the case of seawater before electrochemical reactions take place (Supplementary Fig. S13b). This leakage current increases with each gate sweep, potentially causing electrochemical degradation of the polymer semiconductor and altering the OFET sensor irreversibly. In addition, this effect was found to increase in magnitude in the presence of a higher concentration of ions in the electrolyte (DI water versus seawater, Supplementary Figs S12 versus S14, respectively, and Supplementary Fig. S15). In contrast, the leakage current in the back-gate configuration does not change with additional gate sweeps as the conducting channel is located at the interface between the dielectric and the PII2T-Si polymer (Supplementary Figs S3,S16,S17 and Supplementary Note 3). For the back-gated configuration, we observed an excellent long-term stability, which is preferential for sensing experiments. This stability is shown for the first time with a polymeric semiconductor; we observed that other organic polymers commonly used for sensing (poly(3-hexylthiophene) and poly(2,5-bis(3-hexadecylthiophen-2-yl)thieno[3,2-b]thiophene)) and the reference polymer degraded almost immediately under the same conditions (Supplementary Figs S6 and S7). Further, we fabricated a PII2T-Si OFET on a flexible polyimide substrate and observed similar stability when exposed to seawater (Supplementary Figs S18 and S19). Figure 3c further illustrates the long-term stability of these polymer OFETs. Here the device shown in Fig. 3a is exposed to seawater immediately after its 17-day immersion in DI water. We stress that there is no significant degradation of the OFET’s electrical performance even when it was stored long-term in seawater and monitored for 2 months. Vth,avg remains virtually unchanged (inset Fig. 3c), and the OFET’s outstanding performance demonstrates a very slight drift or diminution of the on/off ratio (>103) even after more than a 3-month exposure to seawater (Supplementary Fig. S16a). The stability was confirmed with four different devices with an average Vth,avg shift of ~13mV per day. The average electrical figures of merit were calculated over four different devices in seawater (Vth~−1.89±1.2 V, μ~0.01±0.004 cm2 Vs−1 and on/off ratio >150, Supplementary Table S1). As salinity level changes can be an important indicator of ecosystem changes14, we also used the OFET to monitor changes in salt concentration. We diluted the seawater by a factor of 10 (0.1 × ) and 100 (0.01 × ) and exposed the PII2T-Si OFET to these solutions. Figure 3d shows the change in Isd over time with a continuous liquid delivery that cycled between these solutions. Isd increases (decreases) for an increase (decrease) in salt concentration. Again, we observed reproducible and stable current plateaus, indicating the extreme stability of this OFET sensor. The observed effect of non-specific interaction of the seawater with the OFET may be attributed to diffusion of charged ions into the conducting channel owing to cracks in the polymeric layer causing an electrochemical doping and hence a change in Isd (ref. 19). In contrast, a slightly positively polarized OFET surface48 may lead to adsorption of charged ions forming an electrical double layer, which electrostatically influences the conductive channel49.

Selective sensing in seawater

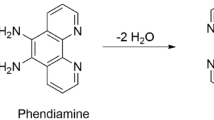

To serve as useful sensors, OFETs must be selective for a particular target. We focused on the detection of mercury (Hg2+) as a proof-of-concept demonstration of selective detection. Hg2+ contamination of groundwater and seawater sources from mine tailings is a critical issue for human health, as it can be bacterially converted to methyl mercury and travel up the food chain, resulting in mercury poisoning50. We engineered selective binding sites for Hg2+ into our OFETs by incorporating DNA-functionalized gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) on the polymer’s surface using a previously developed technique51. AuNPs were spin coated from a block-copolymer matrix and subsequently functionalized with a 33-base thiolated DNA probe (5′-SH-TCA TGT TTG TTT GTT GGC CCC CCT TCT TTC TTA-3′) that had been previously reported to demonstrate selective binding with Hg2+ (Supplementary Fig. S20a)52. The AuNP-decorated polymeric OFET sensors show excellent electrical stability when stored in seawater (Fig. 4). The electrical figures of merit for such devices were calculated (Vth~−1.35 V, μ~0.01 cm2 Vs−1), on/off ratios are at least ~100 but could not be fully extracted since the devices were operated using low source-drain and back-gate voltages to minimize parasitic currents (Supplementary Table S3). To maintain the authenticity of the marine environment, mercury(II) acetate was dissolved in undiluted seawater samples. Figure 5a shows a typical response of Isd over time while delivering alternating solutions of seawater and seawater with dissolved Hg2+ ions (1 mM) to the OFET at a rate of 1 ml min−1. We observed a current increase by a factor of ~3 on introducing of Hg2+ ions. The OFET achieved a stable and reproducible response during cycling between solutions. The change in Isd can be explained by a conformational change in the DNA, which forms a hairpin structure on binding Hg2+ (ref. 52). As a direct consequence of this conformation change, the density of negative charges increases in the vicinity of the OFET’s surface (Supplementary Fig. S20b and Supplementary Note 4). This change induces positive charges in the organic semiconductor, which manifests in the increase in Isd. Remarkably, the high background concentration of salt in seawater (~600 mM) has only little effect on the interaction between Hg2+ and the OFET53 compared with the interaction in DI water, allowing a detection limit down to 10 μM (Supplementary Figs S21 and S22 and Supplementary Note 4). This detection limit may be improved by decreasing the spacing between the AuNPs, to increase the density of the attached DNA54. In this work, the main goal of Hg2+ detection is to demonstrate that selective sensing is possible with OFET sensors even in high salt concentration seawater. Although the present method is less sensitive compared with other reported sensing platforms (Supplementary Table S4), it is highly scalable because of the easy spin-casting fabrication process. Further, it is label free and is able to be deployed in the marine environment. Figure 5b shows the OFET’s selective response for Hg2+ against other important seawater contaminants (Zn2+ and Pb2+). For Hg2+, Isd increases by a factor of ~3 over an extended period of time. The initial sharp drop in Isd for all ions is caused by changing the valve port and is not due an OFET response to the ions; rather, this sudden change in Isd is a result of the OFET’s response to a change in the liquid flow55. For exposure to Zn2+ and Pb2+ ions, Isd recovers quickly to the previously established baseline, a trend similarly observed when liquid flow was changed between two identical seawater samples (inset Fig. 5b). In addition, we studied the response of an OFET decorated with AuNPs but lacking the DNA aptamer. On injection of Hg2+ ions, we observe no response for the OFET lacking the DNA aptamer. This confirms that the presence of the DNA is directly responsible for the sensing response (green straight line, Fig. 5b). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of selective sensing in a marine environment using a polymer OFET.

The Isd versus Vbg characteristics in a back-gate configuration was measured over multiple days while stored continuously in seawater. Black arrows indicate direction of gate sweep. Channel width (w)/length (l) ratio is 80. No degradation of the performance of the OFET is visible. Extracted Vth,avg shifts are almost constant (inset).

(a) Time-resolved measurement of Isd at constant Vsd and Vbg at constant pump speed of 1 ml min−1. Solutions of seawater and 1 mM Hg2+ dissolved in seawater are alternately exposed to OFET, resulting in reproducible plateaus in Isd. (b) Selective response of the OFET sensor to Hg2+ (black line) dissolved in seawater (1 mM), as opposed to its response to Zn2+ (red-dotted line) or Pb2+ (blue-dashed line) dissolved in seawater (both at 1 mM). For AuNPs that were not functionalized with DNA, there was no response of the OFET to dissolved Hg2+ ions (green line). Data collected from three different samples. The small sharp change in Isd immediately following injection of a new solution is a coupling response to switching the automatic valve (inset) that occurs in samples of high ion concentrations. The following Vsd and Vbg values were used: Zn2+, −0.8/−3 V; Pb2+, −0.8/−2.75 V; Hg2+, −0.8/−3 V; no DNA, −0.8/−4 V.

Discussion

We introduced a novel application of our previously reported polymer that can be used for the fabrication of flexible, solution-processable OFETs sensors with high yield and reproducibility. Using the PII2T-Si polymer, we demonstrated stable electrical performance, not only under ambient conditions but also in aqueous environments (DI water and seawater). The fabricated devices show unexpected and remarkably high stability over an extended time period in seawater, one of the harshest aqueous environments in which an OFET sensor can be operated. This observation led to a new field of investigation—the use of an organic polymer as sensor in a marine environment—an application previously inaccessible to organic electronics. Using a simple functionalization scheme, we demonstrated the reproducible and selective detection of Hg2+ contamination in seawater. Our investigation opens an entirely new realm of applications for OFET sensors; the use of organic materials as printable, low-cost and large-area sensors for monitoring aqueous, especially marine, environments is now possible. Altogether, these observations constitute a significant leap forward for the field of organic electronics.

Methods

Device fabrication

Polymer OFET samples were fabricated on highly doped (n++) silicon wafer with  100

100 orientation and a 300-nm SiO2 oxide layer (Silicon Quest International). Before functionalization, the wafer was cleaned for 15 min with ultraviolet ozone (Jelight Company). The substrate was transferred into a glovebox and immersed in a solution of mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane (40 μl, Gelest) and toluene (20 ml, Sigma-Aldrich) to form a self-assembled monolayer on the SiO2 (ref. 33) Pieces (2.5 × 2.5 cm2) were cut from the wafer and used for device formation. Au (40 nm) source-drain electrodes were thermally evaporated (Thermionics Laboratories Inc.) through a shadow mask on a rotating substrate at a rate of 4 Å s−1, with a channel width (w) of 4,000 μm and length (l) of 50 μm (w/l=80). The channel w/l ratio was 320 for the long-term stability measurements. The mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane monolayer was subsequently removed through a second 15 min exposure to the ultraviolet ozone. Subsequently, the devices were returned to the glovebox and a dense, crystalline monolayer of octadecyltrichlorosilane was deposited on the exposed SiO2 to enhance the electrical performance of the organic polymer33. For seawater cycling and salinity tests (Fig. 3b,d) a bare silicon wafer with SiO2 (

orientation and a 300-nm SiO2 oxide layer (Silicon Quest International). Before functionalization, the wafer was cleaned for 15 min with ultraviolet ozone (Jelight Company). The substrate was transferred into a glovebox and immersed in a solution of mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane (40 μl, Gelest) and toluene (20 ml, Sigma-Aldrich) to form a self-assembled monolayer on the SiO2 (ref. 33) Pieces (2.5 × 2.5 cm2) were cut from the wafer and used for device formation. Au (40 nm) source-drain electrodes were thermally evaporated (Thermionics Laboratories Inc.) through a shadow mask on a rotating substrate at a rate of 4 Å s−1, with a channel width (w) of 4,000 μm and length (l) of 50 μm (w/l=80). The channel w/l ratio was 320 for the long-term stability measurements. The mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane monolayer was subsequently removed through a second 15 min exposure to the ultraviolet ozone. Subsequently, the devices were returned to the glovebox and a dense, crystalline monolayer of octadecyltrichlorosilane was deposited on the exposed SiO2 to enhance the electrical performance of the organic polymer33. For seawater cycling and salinity tests (Fig. 3b,d) a bare silicon wafer with SiO2 ( 100

100 orientation, n++, Silicon Quest International) has been spin coated (4,500 r.p.m., 60 s) with two layers (~80 nm) of a poly(4-vinylphenol) cross-linked with 4,4′-(hexafluoroisopropylidene)diphthalic anhydride dielectric annealed on a 120-°C hotplate for several hours51. Afterwards, Au electrodes were evaporated. An isoindigo-based conjugated polymer with solubilizing siloxane-terminated side chains (PII2T-Si) was synthesized as reported previously33 and used as the organic semiconductor. Inside a glovebox, PII2T-Si was dissolved in chloroform (4 mg ml−1) and heated to 58 °C with stirring for 20 min. One hundred and twenty microlitres of the dissolved polymer was spin coated on top of the electrodes at 1,000 r.p.m. for 60 s. To optimize electrical performance in aqueous environments, a second layer of PII2T-Si was immediately spin coated. The thickness of each PII2T-Si film was ~80 nm. Subsequently, the samples were annealed for 1 h on a hotplate at 180 °C and then allowed to cool down slowly. The fabricated devices were removed from the glovebox and stored long-term under ambient conditions with no further treatment.

orientation, n++, Silicon Quest International) has been spin coated (4,500 r.p.m., 60 s) with two layers (~80 nm) of a poly(4-vinylphenol) cross-linked with 4,4′-(hexafluoroisopropylidene)diphthalic anhydride dielectric annealed on a 120-°C hotplate for several hours51. Afterwards, Au electrodes were evaporated. An isoindigo-based conjugated polymer with solubilizing siloxane-terminated side chains (PII2T-Si) was synthesized as reported previously33 and used as the organic semiconductor. Inside a glovebox, PII2T-Si was dissolved in chloroform (4 mg ml−1) and heated to 58 °C with stirring for 20 min. One hundred and twenty microlitres of the dissolved polymer was spin coated on top of the electrodes at 1,000 r.p.m. for 60 s. To optimize electrical performance in aqueous environments, a second layer of PII2T-Si was immediately spin coated. The thickness of each PII2T-Si film was ~80 nm. Subsequently, the samples were annealed for 1 h on a hotplate at 180 °C and then allowed to cool down slowly. The fabricated devices were removed from the glovebox and stored long-term under ambient conditions with no further treatment.

PDPPTT and PIID2T-C3 solutions where prepared according to reported literature methods42,43. Inside a glovebox, PDPPTT was dissolved in dichlorobenzene (5 mg ml−1) and heated to 160 °C with stirring for 20 min. One hundred and twenty microlitres of the dissolved polymer was spin coated on top of the electrodes at 1,000 r.p.m. for 60 s. Subsequently, the samples were annealed for 5 min on a hotplate at 160 °C and then allowed to cool down slowly. PIID2T-C3 was dissolved in chloroform (4 or 2 mg ml−1) and heated to 58 °C with stirring for 20 min. One hundred and twenty microlitres of the dissolved polymer was spin coated on top of the electrodes at 1,000 r.p.m. for 40 s. Subsequently, the samples were annealed for 30 min on a hotplate at 175 °C and then allowed to cool down slowly.

Flexible OFETs were fabricated on 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 pieces of polyimide. A bisbenzocyclobutene smoothing layer was spin coated in a glovebox (3,000 r.p.m., 60 s) and annealed for several hours. Subsequently, an ultrathin (~40 nm) dielectric layer poly(4-vinylphenol)-cross-linked 4,4′-(hexafluoroisopropylidene)diphthalic anhydride was spin coated (4,500 r.p.m., 60 s) and annealed on a 120 °C hotplate for several hours. Gold electrodes were subsequently evaporated and the organic polymer was deposited via spin coating as above described.

AuNP formation and DNA functionalization were performed as previously described51.

Electrical measurements

All measurements were performed under ambient conditions at room temperature. A constant source-drain potential was applied to the electrodes (Vsd) while measuring the source-drain current (Isd) with a source-meter (Keithley 2635A). The back-gate potential (Vbg) was applied and swept using a second source-meter (Keithley 2400). For electrical testing in aqueous environments, a PDMS flow cell with an internal volume of 66 μl was mounted directly on the device. Solutions were delivered to the device by a HPLC digital pump (Lab Alliance Series III) through polyether ether ketone (PEEK) tubing (0.0625′′ internal diameter) while an automatic 10-port valve (VICI Cheminert Line) was used to switch between solutions. For liquid-gating experiments, a flow-through Ag/AgCl reference electrode (Microelectrodes Inc.) was placed in line with the tubing in close vicinity to the flow cell. Before electrical measurements in aqueous environments, the samples were equilibrated for 1 h in contact with the solution. For time-dependent measurements, a working point at fixed source-drain voltage and gate voltage was chosen. All measurements were controlled by a self-made LabView program.

Solution preparation

Seawater samples were collected from the North Pacific Ocean at Half-Moon Bay and La Honda (CA, USA). These samples where filtered through a 0.45-μm filter (Nalgene, ThermoScientific) to remove large particulates. For salinity experiments, filtered seawater was diluted to 0.1 × and 0.01 × with DI water (Gibco). For electrolyte-gating measurements in NaCl solution, sodium chloride salt (99% grade, EMD) was dissolved in DI water. For selectivity measurements, mercury(II) acetate (98+% grade, Alfa Asear), zinc(II) acetate (99.999% grade, Sigma-Aldrich) and lead(II) chloride (99.999% grade, Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved in filtered seawater or DI water.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Knopfmacher, O. et al. Highly stable organic polymer field-effect transistor sensor for selective detection in the marine environment. Nat. Commun. 5:2954 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3954 (2014).

References

Angione, M. D. et al. Carbon based materials for electronic bio-sensing. Mater. Today 14, 424–433 (2011).

Makowski, M. S. & Ivanisevic, A. Molecular analysis of blood with micro-/nanoscale field-effect-transistor biosensors. Small 7, 1863–1875 (2011).

Cui, Y., Wei, Q., Park, H. & Lieber, C. M. Nanowire nanosensors for highly sensitive and selective detection of biological and chemical species. Science 293, 1289–1292 (2001).

McAlpine, M. C., Ahmad, H., Wang, D. & Heath, J. R. Highly ordered nanowire arrays on plastic substrates for ultrasensitive flexible chemical sensors. Nat. Mater. 6, 379–384 (2007).

Bergveld, P. Thirty years of ISFETOLOGY: what happened in the past 30 years and what may happen in the next 30 years. Sensors Actuat. B 88, 1–20 (2003).

Zhang, G.-J. et al. DNA sensing by silicon nanowire: charge layer distance dependence. Nano Lett. 8, 1066–1070 (2008).

Tang, X. et al. Carbon nanotube DNA sensor and sensing mechanism. Nano Lett. 6, 1632–1636 (2006).

Bunimovich, Y. L. et al. Quantitative real-time measurements of DNA hybridization with alkylated nonoxidized silicon nanowires in electrolyte solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 16323–16331 (2006).

Wang, W., Chen, C. & Lin, K. Label-free detection of small-molecule–protein interactions by using nanowire nanosensors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 102, 3208–32126 (2005).

Han, Y., Offenhaeusser, A. & Ingebrandt, S. Detection of DNA hybridization by a field-effect transistor with covalently attached catcher molecules. Surf. Interface Anal. 38, 176–181.

Noy, A. Bionanoelectronics. Adv. Mater. 23, 807–820 (2011).

Cobben, P. L. H. M. et al. Transduction of selective recognition of heavy metal ions by chemically modified field effect transistors (CHEMFETs). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114, 10573–10582 (1992).

Forzani, E. S. et al. Tuning the chemical selectivity of SWNT-FETs for detection of heavy-metal ions. Small 2, 1283–1291 (2006).

Mills, G. & Fones, G. A review of in situ methods and sensors for monitoring the marine environment. Sensor Rev. 32, 17–28 (2012).

Vu, X. T. et al. Top-down processed silicon nanowire transistor arrays for biosensing. Physica Status Solidi A 206, 426–434 (2009).

Bergveld, P. Development of an ion-sensitive solid-state device for neurophysiological measurements. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 17, 70–71 (1970).

Heller, I. et al. Identifying the mechanism of biosensing with carbon nanotube transistors. Nano Lett. 8, 591–595 (2008).

Shao, Y. et al. Graphene based electrochemical sensors and biosensors: a review. Electroanalysis 22, 1027–1036 (2010).

Roberts, M. E. et al. Water-stable organic transistors and their application in chemical and biological sensors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 12134–12139 (2008).

Dodabalapur, A., Torsi, L. & Katz, H. E. Organic transistors: two-dimensional transport and improved electrical characteristics. Science 268, 270–271 (1995).

Bernards, Daniel A., Owens, Róisín M. & Malliaras, G. G. Organic Semiconductors in Sensor Applications Springer (2008).

Stoliar, P. et al. DNA adsorption measured with ultra-thin film organic field effect transistors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 24, 2935–2938 (2009).

Berggren, M. & Richter-Dahlfors, A. Organic Bioelectronics. Adv. Mater. 19, 3201–3213 (2007).

Torsi, L., Dodabalapur, A., Sabbatini, L. & Zambonin, P. Multi-parameter gas sensors based on organic thin-film-transistors. Sensors Actuat. B 67, 312–316 (2000).

Schwartz, G. et al. Flexible polymer transistors with exceptionally high pressure sensitivity for application in electronic skin and health monitoring. Nat. Commun. 4, 1859 (2013).

Bobbert, P. A., Sharma, A., Mathijssen, S. G. J., Kemerink, M. & De Leeuw, D. M. Operational stability of organic field-effect transistors. Adv. Mater. 24, 1146–1158 (2012).

Lin, P. & Yan, F. Organic thin-film transistors for chemical and biological sensing. Adv. Mater. 24, 34–51 (2012).

Guo, X. et al. Chemoresponsive monolayer transistors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 11452–11456 (2006).

Angione, M. D. et al. Interfacial electronic effects in functional biolayers integrated into organic field-effect transistors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 6429–6434 (2012).

Khan, H. U., Roberts, M. E., Knoll, W. & Bao, Z. Pentacene based organic thin film transistors as the transducer for biochemical sensing in aqueous media. Chem. Mater. 23, 1946–1953 (2011).

Mabeck, J. T. & Malliaras, G. G. Chemical and biological sensors based on organic thin-film transistors. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 384, 343–353 (2006).

Bernards, D. A. & Malliaras, G. G. Steady-state and transient behavior of organic electrochemical transistors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 17, 3538–3544 (2007).

Mei, J., Kim, D. H., Ayzner, A. L., Toney, M. F. & Bao, Z. Siloxane-terminated solubilizing side chains: bringing conjugated polymer backbones closer and boosting hole mobilities in thin-film transistors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 20130–20133 (2011).

Knopfmacher, O. et al. Nernst limit in dual-gated Si-nanowire FET sensors. Nano Lett. 10, 2268–2274 (2010).

Ucurum, C., Goebel, H., Yildirim, F. a., Bauhofer, W. & Krautschneider, W. Hole trap related hysteresis in pentacene field-effect transistors. J. Appl. Phys. 104, 084501–084506 (2008).

Kergoat, L. et al. A water-gate organic field-effect transistor. Adv. Mater. 22, 2565–2569 (2010).

Buth, F., Kumar, D., Stutzmann, M. & Garrido, J. A. Electrolyte-gated organic field-effect transistors for sensing applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 153302–153304 (2011).

Cramer, T. et al. Double layer capacitance measured by organic field effect transistor operated in water. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 143302–143305 (2012).

Egginger, M., Bauer, S., Schwödiauer, R., Neugebauer, H. & Sariciftci, N. S. Current versus gate voltage hysteresis in organic field effect transistors. Monatsh. Chem. 140, 735–750 (2009).

Park, Y. M. & Salleo, A. Dual-gate organic thin film transistors as chemical sensors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 133307–133309 (2009).

Kergoat, L. et al. DNA detection with a water-gated organic field-effect transistor. Org. Electron. 13, 1–6 (2012).

Li, J. et al. A stable solution-processed polymer semiconductor with record high-mobility for printed transistors. Sci. Rep. 2, 754 (2012).

Lei, T., Dou, J.-H. & Pei, J. Influence of alkyl chain branching positions on the hole mobilities of polymer thin-film transistors. Adv. Mater. 24, 6457–6461 (2012).

Głowacki, E. D. et al. Hydrogen-bonded semiconducting pigments for air-stable field-effect transistors. Adv. Mater. 25, 1563–1569 (2013).

Ho, C. K., Robinson, A., Miller, D. R. & Davis, M. J. Overview of sensors and needs for environmental monitoring. Sensors 5, 4–37 (2005).

Natalio, F. et al. Vanadium pentoxide nanoparticles mimic vanadium haloperoxidases and thwart biofilm formation. Nat. Nanotech. 7, 530–535 (2012).

Libes, S. An Introduction to Marine Biogeochemistry John Wiley & Sons (1991).

Palermo, V., Palma, M. & Samorì, P. Electronic characterization of organic thin films by kelvin probe force microscopy. Adv. Mater. 18, 145–164 (2006).

Sirringhaus, H. Device physics of solution-processed organic field-effect transistors. Adv. Mater. 17, 2411–2425 (2005).

Gehrke, G. E., Blum, J. D. & Marvin-DiPasquale, M. Sources of mercury to San Francisco Bay surface sediment as revealed by mercury stable isotopes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 691–705 (2011).

Hammock, M. L., Sokolov, A. N., Stoltenberg, R. M., Naab, B. D. & Bao, Z. Organic transistors with ordered nanoparticle arrays as a tailorable platform for selective, in situ detection. ACS Nano 6, 3100–3108 (2012).

Wang, Z., Heon Lee, J. & Lu, Y. Highly sensitive ‘turn-on’ fluorescent sensor for Hg2+ in aqueous solution based on structure-switching DNA. Chem. Commun. 7, 6005–6007 (2008).

Tarasov, A. et al. Understanding the electrolyte background for biochemical sensing with ion-sensitive field-effect transistors. ACS Nano 6, 9291–9298 (2012).

Hammock, M. L., Knopfmacher, O., Naab, B. D., Tok, J. B.-H. & Bao, Z. Investigation of protein detection parameters using nanofunctionalized organic field-effect transistors. ACS Nano 7, 3970–3980 (2013).

Someya, T., Dodabalapur, A. & Gelperin, A. Integration and response of organic electronics with aqueous microfluidics. Langmuir 18, 5299–5302 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Tok for many helpful discussions and M. Vosgueritchian for SEM pictures. O.K. acknowledges financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (PBBSP2-138715). M.L.H. acknowledges funding from the National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate (NDSEG) Fellowship (32 CFR 168a) and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. We also acknowledge funding from the National Science Foundation (ECCS 1101901) and Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-12-1-0190). J.M. and A.L.A. acknowledge the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Postdoctoral Program in Environmental Chemistry. G.S acknowledges funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SCHW 1556/2-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.K. designed and performed the experiments, fabricated the devices and analysed the data. M.L.H. functionalized the samples, measured them and performed data analysis. A.L.A. and J.M synthesized the organic polymer. G.S. contributed to the long-term stability tests and data analysis. T.L. and J.P synthesized the PIID2T-C3 polymer. Z.B. directed the project. All authors co-wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S22, Supplementary Tables S1-S4, Supplementary Notes 1-4 and Supplementary References (PDF 2186 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Knopfmacher, O., Hammock, M., Appleton, A. et al. Highly stable organic polymer field-effect transistor sensor for selective detection in the marine environment. Nat Commun 5, 2954 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3954

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3954

This article is cited by

-

Chemical modification and doping of poly(p-phenylenes): A theoretical study

Journal of Molecular Modeling (2024)

-

Factors affecting the electrical conductivity of conducting polymers

Carbon Letters (2023)

-

Electrolyte-gated organic field-effect transistors based on 2,6-dioctyltetrathienoacene as a convenient platform for fabrication of liquid biosensors

Russian Chemical Bulletin (2022)

-

A thriving decade: rational design, green synthesis, and cutting-edge applications of isoindigo-based conjugated polymers in organic field-effect transistors

Science China Chemistry (2022)

-

Recent advances in field-effect transistors for heavy metal ion detection

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.