Abstract

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and imaging (MRI) play an indispensable role in science and healthcare but use only a tiny fraction of their potential. No more than ≈10 p.p.m. of all 1H nuclei are effectively detected in a 3-Tesla clinical MRI system. Thus, a vast array of new applications lays dormant, awaiting improved sensitivity. Here we demonstrate the continuous polarization of small molecules in solution to a level that cannot be achieved in a viable magnet. The magnetization does not decay and is effectively reinitialized within seconds after being measured. This effect depends on the long-lived, entangled spin-order of parahydrogen and an exchange reaction in a low magnetic field of 10−3 Tesla. We demonstrate the potential of this method by fast MRI and envision the catalysis of new applications such as cancer screening or indeed low-field MRI for routine use and remote application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

All conventional magnetic resonance (MR) methods employ only a few p.p.m. of the potentially available signal. This is because the total thermal energy (kBT) of any living system greatly exceeds the energy of nuclear magnetic moments within a magnetic field which is smaller than 104 Tesla. Hence, the nuclear magnetic moments align almost randomly and almost cancel each other out.

Statistically speaking, it is only about 3 p.p.m. of the magnetic moments of hydrogen nuclei that are observed in a magnetic field of 1 Tesla. In the Earth’s magnetic field, this figure reduces to ≈2 × 10−10. Indeed, the main reason that we can detect an MR signal at all is the vast number of duplicate molecules, and hence nuclei, that are present; most systems investigated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contain more nuclei than are reflected in Avogadro’s constant (≈1023).

The dream to bypass these thermal equilibrium constraints through hyperpolarization has inspired many researchers over the past decades1,2,3. Some methods have reached application in humans4,5 and chemistry6,7. Despite this success, the following three major impediments to fully embrace hyperpolarization remain: (a) its limited lifetime, (b) its single-use character and (c) the requirement of an external polarizer apparatus.

Here we illustrate a method that has the potential to overcome these challenges. The presented method works by continuously producing a hyperpolarized sample of small molecules in solution at a low magnetic field of ≈5 mT. The magnetization does not decay and is reinstated after signal detection. We demonstrate the potential of this method by NMR and MRI at very low field, and believe that this fundamentally new approach will trigger and catalyse the development of new application in the fields of NMR, MRI and beyond.

Results

Continuously renewing hyperpolarization

The presented method works by continuously producing a hyperpolarized sample of small molecules in solution by means of a chemical exchange reaction with parahydrogen at a low magnetic field of ≈5 mT. Over the time course of these experiments, for example, 700 s, there is no decrease in the observed hyperpolarization (HP) level as reflected in Fig. 1. Furthermore, after read-out by a 90° pulse, the hyperpolarized state is restored to equilibrium within just a few seconds according to a mono exponential recovery time constant Tpr of 5.5 s (Supplementary Figs S1 and S2), and therefore traditional multiple scan options become accessible. To reach the equivalent polarization figure via the thermal equilibration of magnetization, a few hundred Tesla would be required (Supplementary Fig. S2). This option is neither practical nor likely to be available any time soon. The hardware requirements for this method however are minimal, as it is based on signal amplification by reversible exchange (SABRE), which was reported in 2009 (ref. 8) and has stimulated much discussion in the literature. SABRE has been successfully used to hyperpolarize many different molecules, including purines and pyrimidines9, amino acids, peptides10 and various drugs11. The new effect where the polarization is continuously renewed is schematically depicted in Fig. 2.

Absolute polarization produced during the continuous hyperpolarization process. Each data point represents the peak area of a hyperpolarized pyridine resonance as monitored by a cascade of 90° excitation pulses that are separated by a variable recovery delay (TR/s); quantification is based on the signal from a thermally polarized water sample at 5 mT. After depletion by excitation, the hyperpolarization level recovers with a time constant of 5 s to a level of 10−3, which equates with a thermal 1H-polarization field of between 102 and 103 Tesla. The estimated concentration of H2 in this solution is 4 mM.

The para order of hydrogen is transformed to hyperpolarization by reversible exchange and at least partially lost in the process; the hyperpolarized signal is detected and is thus depleted by radio frequency (RF); the process continues and, depending on the para order available, hyperpolariaztion is restored. Note that pH2 is not affected by the application of RF pulses thus retaining its spin order, and that as SABRE polarizes not only 1H but also other biomedically relevant nuclei such as 13C, 19F, 31P and 15N.

Repolarization of individual molecules

As the HP state is continuously restored by this method, its lifetime is no longer a concern. Similarly, the ‘single use’ of each hyperpolarized molecule is circumvented as each molecule of the solution is repolarized. This new phenomenon allows for the repeated observation of each molecule and fast signal averaging on a timescale which was hitherto unavailable.

The need for more than one bolus of hyperpolarized molecules was realized before and is reflected by a substantial body of work and interest in the field. Most methods, however, were based on replenishing the supply of hyperpolarized molecules by appropriate methods. Optical methods provide a continuous flow of hyperpolarized molecules12: Liquid-state Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (DNP) has demonstrated sequential hyperpolarization of multiple samples to increase its throughput, and continuous hyperpolarization in the solid state13, and pH2-based methods were used to generate long-lasting hyperpolarized signals by gradually hydrogenating and thus hyperpolarizing a given sample (by limiting the supply of pH2)14,15.

The method presented here is fundamentally different. Each molecule is repolarized over and over again to a level that exceeds any thermal polarization available today. In fact, the effect described here is for all practical means — for molecules that can be polarized — equivalent to working in thermal equilibrium in a magnetic field of a few hundred Tesla. Modern MR methods rely heavily on the property of restoring magnetization and use it hundreds of times to generate one image. The full range of MRI methods thus becomes available, whereas ‘once-only’ hyperpolarization requires special techniques dealing with the limited availability of the magnetization16,17.

Here we open this highly interesting concept further, showing the continuous of hyperpolarization spins to an equilibrium polarization, which is governed by relaxation and repolarization, and which is being restored after signal detection within seconds.

Internal hyperpolarization

For a biomedical application, the third challenge of transferring hyperpolarization, that of inducing the hyperpolarization process in vivo, remains. A closer look at pH2 would suggest it to be an ideal candidate to transfer spin order in vivo, as this spin-0 particle is impervious to depletion by radio frequency excitation. In fact, it is protected as a singlet, and consequently the lifetime of pH2 extends to weeks. Being the smallest gaseous molecule, it is highly diffusive even within biological tissue and has been used as a therapeutic agent in humans; active take up by the lungs achieves concentrations between μM and mM in the blood in vivo18. Interestingly, the concentration of H2 in the solution of Fig. 1 is of the order of 4 mM (ref. 19) and therefore suggestive of a viable in vivo concentration. Thus, pH2 may transport spin order to biological tissue in vivo.

The main challenge to transforming pH2’s invisible spin order into observable polarization in vivo will be the development of a suitable biocompatible catalyst. For continuous HP, a biocompatible catalyst would be similar in concept to a Gadolinium chelate, which is used in MR examinations around the world. Alternatively, such a catalyst might be targeted, for example, to cancer cells if specificity is required. As pH2 is also much smaller than the cryptophane cages used for HyperCEST12, it would appear feasible to hyperpolarize exogenous or endogenous molecules, including ATP and its derivates (Fig. 3), which are highly concentrated around some cancer cells20. Further, as one catalyst molecule hyperpolarizes many target molecules, multiple times, the loading need not be high. Indeed, signal may be acquired until the required signal-to-noise or resolution is achieved.

Towards application in vivo

The catalyst we use for these initial proof-of-principle experiments was designed for the out-of-body use explicitly, and it will agglomerate in solutions containing sodium ions. Dedicated catalysts for in vivo use are currently under development. The present catalyst, however, is functional to some extent in ethanol and water–ethanol (9:1) solutions. The polarization level is however related to the solvent, and moving from methanol to ethanol and from ethanol to 10% ethanol in water reduced the rates of ligand exchange and consequently lowered the levels of polarization.

The option of hyperpolarization in a dilute ethanol solution therefore offers an attractive route to in vivo experiments. Initial experiments with this catalyst in blood showed continuous hyperpolarization but at a lower level compared with the pure solution (Supplementary Figs S4 and S5).

Application to fast low-field MRI

We used MRI to exemplify the potential of the method. Given an equilibrium polarization equivalent to that of a few hundred Tesla, no superconducting magnet is required. Instead, we use precession in the Earth’s magnetic field to obtain high-resolution 1H-MR images of the continuously HP molecules at very low concentration, much faster than acquiring images of water (Fig. 4). Note that the tracer (≈101 mM) and catalyst (≈100 mM) are much less concentrated than water or biological tissue (≈102 M).

Two-dimensional projection images of continuously hyperpolarized, low-concentration agents with an in-plane resolution of 1 mm2 were acquired in 4.16 min (left: 3 ml, 80 mM), whereas 2.16 h were required to image water at much higher 1H concentration (right: 6 ml, 56 M, 32 averages, prepolarized at 20 mT).

While in this example, only one acquisition is required for high-resolution MRI of ≈101 mM tracer and ≈100 mM catalyst, the concentrations may be lowered much further by employing signal averaging (because HP is a continuously ongoing process). These results shed light on the potential for molecular imaging of targeted tracers tagged with SABRE catalysts. Normally, the signal provided by a targeted agent is much too low for direct MR detection. However, continuous hyperpolarization provides a strongly increased signal, which is reinstated within seconds and can be acquired anew for multiple signal aquisitions. It may also be worthwhile to investigate the transfer, and accumulation, of long-lived spin-order at zero field. A subsequent high-field MR image of 1H or X nuclei may highlight the targeted structures, along with the anatomical reference.

Discussion

Aside from biomedical application, it is worthwhile to consider the potential use of continuous hyperpolarization to chemical analysis. It has been demonstrated that low-field or even Earth-field NMR, which generally lacks chemical shift resolution, may be employed to provide spectra governed by the J-coupling constants. Whereas this approach requires elaborate processing, and may be difficult for large spin systems, nevertheless, the signal gain provided by continuous hyperpolarization is likely to lower the limit of detection significantly21,22.

Evading the need for strong, superconducting magnets, continuous HP at low field provides restoring magnetization beyond what is possible with current superconducting magnets. It paves the way for fast, low-field MRI beyond the limit of the Boltzmann distribution, and may enable highly sensitive molecular imaging of targeted agents. Given the minimal hardware requirements and pH2’s long lifetime, these applications may be realized in devices for remote applications.

It should be emphasized that continuous hyperpolarization as described here does not provide native anatomical contrast. Even when a catalyst for in vivo or even human use becomes available and enables truly molecular MRI, it will supplement rather than replace standard high-resolution MRI with its richness of inherent contrast.

Rather than competing with high-resolution MRI, our technique may be expected to join other molecular imaging modalities like positron emission tomography and bioluminescence imaging.

Although the application to humans remains an ultimate goal of our studies, more imminent biomedical applications of this technique will include in vitro applications of cells, cell suspensions and anatomic specimens as well as experiments in small animals.

These experiments are much easier to realize and promise new insights both with respect to the technology as well as the understanding of the relevant biochemistry of polarizable molecules. These steps are not only necessary to pave the way to human applications, but may constitute relevant biomedical research in their own right.

Methods

Chemistry

The solution containing SABRE catalyst and pyridine was prepared as described before; 2H4-methanol, methanol or ethanol–water (1:9) was used to dissolve the catalyst Ir(1,5-cyclooctadeine)(1,3-Bis (2,4,6-trimethylphenyl) imidazolium) Cl (mw=639,67 g mol−1, the University of York, UK)9).

For low-field NMR (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S2), 4.3 ml, 14 mg and 116 mg of solvent, catalyst and pyridine, respectively, were typically used. For high-field NMR (Fig. 3), 6.1 μMol adenine and 11 μMol catalyst, or 1.2 μMol adenosine and 7.5 μMol catalyst, were added to 0.6 ml of 2H4-methanol, which was heated and sonicated to help dissolution, degassed by freeze-pump-thaw cycles before pH2 was added at 3 bar.

Parahydrogen

Hydrogen gas (99.999%) was enriched to >95% parahydrogen by catalytic conversion at low temperature (T=21 K) and stored in an aluminium cylinder at room temperature23.

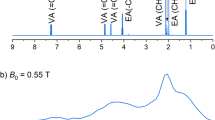

High-field NMR

Standard 5 mm sample tubes were employed for pulse-acquire 1H NMR at 400 MHz (Fig. 3, Avance II, Bruker, Germany). For SABRE, the sample was pressurized with 3 bar pH2, manually shaken at approximately Earth field and quickly transferred to high field for detection. A reference spectrum was acquired after thermal equilibrium was reinstated.

Low-field NMR

On the basis of an earlier design24, a MR unit was constructed for fields up to 6 mT, suitable for transmit-receive and cross-coil mode, that is separated transmit and receive coil. A digital interface (NI DAC USB 6251, National Instruments, USA) and custom software (LabView or MatLab) was used to control the experiments. Flip angles were calibrated using the signal of water in thermal equilibrium to an estimated uncertainty of 2%. pH2 was supplied continuously through thin tubing into a cylinder (V≈30 ml, see ref. 24), or injected for ≈1 s into an reaction chamber made from polysulfone (V≈10 ml).

Signal was acquired by non-localized pulse-acquisition experiments. A compensation winding on the B0 magnet provided for a linewidth of the order of 101 Hz.

Quantification methods

Low-field NMR data were quantified by fitting a complex lorentian function to the resonance to obtain its area (simplex algorithm, Matlab, The MathWorks, USA). The hyperpolarization yield was quantified with respect to a water resonance in thermal equilibrium (Supplementary Fig. S2), assuming 25% of MR-mute para water.

At resonance frequencies of the order of 250 kHz and line widths of 10–50 Hz, the chemical shift displacements of individual nuclei, which are only a few p.p.m., are not resolved. Thus, the observed resonance at low field is a superposition of all contributing nuclei and the polarization reported here is per molecule of pyridine, which contains five hydrogens. The individual protons polarization may thus be a fifth of this value.

Low-field MRI

A commercially available low-field MR imager was used (TerraNova, Magritek, NZ). For conventional Earth-field imaging, a 20-mT field was generated for 4 s to increase the thermal polarization of water. The signal was detected subsequently in the Earth’s field, the homogeneity of which was improved by automatic shimming before.

To image a hyperpolarized sample, a reaction chamber was placed inside the field-cycling device. A field of ≈6.5 mT was applied for 4 s to enable continuous repolarization. Subsequently, signal excitation, spatial encoding and read-out was performed at Earth field.

In either case, imaging was limited to read one k-space line in 8 s, thus much potential remains for acceleration. Typical imaging parameters were the following: two-dimensional projection spin-echo MRI, field of view (FOV) 64 mm2, matrix size 322, 1 × zero filling, interpolated resolution 1 mm2, echo time (TE) 150 ms, repetition time (TR) 8 s. Low-field MRI data were evaluated using the manufacturer’s software.

Continuous HP

The repolarization time constant Tpr was obtained by fitting a mono exponential, saturation-recovery-type function to the signal acquired after a varying repolarization interval (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S3). When pH2 was supplied once, the signal exhibited an overall decrease with time (mono exponential decay with ≈400 s time constant, Supplementary Fig. S1). We attribute the slow signal decay to spin-order loss of pH2 because of relaxation and transfer to pyridine.

For experiments in blood, 2 ml fresh native human blood were added slowly to a solution of 88 mg pyridine in 2 ml ethanol and 11 mg catalyst while the signal was monitored by 90° acquisitions interleaved by 10 s repolarization delays at 6.5 mT. Informed consent was obtained from the donor. While blood was added, the supply of pH2 was halted (Supplementary Fig. S4). Two representative spectra, before and after the injection of blood, are shown (Supplementary Fig. S5). Note that by the end of the acquisitions, the liquid was coagulated and the signal dropped to approximately a tenth of its initial value.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Hövener, J.-B. et al. A hyperpolarized equilibrium for magnetic resonance. Nat. Commun. 4:2946 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3946 (2013).

References

Bowers, C. R. & Weitekamp, D. P. transformation of symmetrization order to nuclear-spin magnetization by chemical-reaction and nuclear-magnetic-resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 57, 2645–2648 (1986).

Abragam, A. & Goldman, M. Principles of dynamic nuclear-polarization. Rep. Prog. Phys. 41, 395–467 (1978).

Golman, K. et al. C-13-angiography. Acad. Radiol. 9, S507–S510 (2002).

Bachert, P. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging of airways in humans with use of hyperpolarized 3He. Magn. Reson. Med. 36, 192–196 (1996).

Nelson, S. J. et al. Metabolic imaging of patients with prostate cancer using hyperpolarized [1-13C] pyruvate. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 198ra108 (2013).

Frydman, L. & Blazina, D. Ultrafast two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of hyperpolarized solutions. Nat. Phys. 3, 415–419 (2007).

Lloyd, L. S. et al. Utilization of SABRE-derived hyperpolarization to detect low-concentration analytes via 1D and 2D NMR methods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 12904–12907 (2012).

Adams, R. W. et al. Reversible interactions with para-hydrogen enhance NMR sensitivity by polarization transfer. Science 323, 1708–1711 (2009).

Cowley, M. et al. Iridium N-heterocyclic carbene complexes as efficient catalysts for magnetization transfer from para-hydrogen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 6134–6137 (2011).

Glöggler, S. et al. Para-hydrogen induced polarization of amino acids, peptides and deuterium–hydrogen gas. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 13759–13764 (2011).

Glöggler, S. et al. Selective drug trace detection with low-field NMR. Analyst (Lond). 136, 1566 (2011).

Schröder, L., Lowery, T. J., Hilty, C., Wemmer, D. E. & Pines, A. Molecular imaging using a targeted magnetic resonance hyperpolarized biosensor. Science 314, 446–449 (2006).

Batel, M. et al. A multi-sample 94 GHz dissolution dynamic-nuclear-polarization system. J. Magn. Reson. 214, 166–174 (2012).

Roth, M. et al. Continuous 1H and 13C signal enhancement in NMR spectroscopy and MRI using parahydrogen and hollow fibre membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 8358–8362 (2010).

Messerle, B. A., Sleigh, C. J., Partridge, M. G. & Duckett, S. B. Structure and dynamics in metal phosphine complexes using advanced NMR studies with para-hydrogen induced polarisation. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1429–1436 (1999).

Leupold, J., Mansson, S., Petersson, J. S., Hennig, J. & Wieben, O. Fast multiecho balanced SSFP metabolite mapping of (1)H and hyperpolarized (13)C compounds. Mag. Res. Mat. Biol. Phy. Med. 22, 251–256 (2009).

Perman, W. H. et al. Fast volumetric spatial-spectral MR imaging of hyperpolarized (13)C-labeled compounds using multiple echo 3D bSSFP. J. Mag. Reson. 28, 459–465 (2010).

Ohsawa, I. et al. Hydrogen acts as a therapeutic antioxidant by selectively reducing cytotoxic oxygen radicals. Nat. Med. 13, 688–694 (2007).

Radhakrishnan, K., Ramachandran, P. A., Brahme, P. H. & Chaudhari, R. V. Solubility of hydrogen in methanol, nitrobenzene, and their mixtures experimental data and correlation. J. Chem. Eng. Data 28, 1–4 (1983).

Pellegatti, P. et al. Increased level of extracellular ATP at tumor sites: in vivo imaging with plasma membrane luciferase. PLoS One 3, e2599 (2008).

Theis, T. et al. Zero-field NMR enhanced by parahydrogen in reversible exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3987–3990 (2012).

McDermott, R. et al. Liquid-state NMR and scalar couplings in microtesla magnetic fields. Science 295, 2247–2249 (2002).

Hövener, J.-B. et al. A continuous-flow, high-throughput, high-pressure parahydrogen converter for hyperpolarization in a clinical setting. NMR Biomed. 26, 124–131 (2013).

Borowiak, R. et al. A battery-driven, low-field NMR unit for thermally and hyperpolarized samples. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phy. 26, 491–499 (2013).

Acknowledgements

J.B.H. was supported by the Innovationsfond Baden-Würtemberg and Academy of Excellence of the German Research Foundation. J.G.K. is supported by the European Research Commission. We also thank the Wellcome Trust (092506 and 098335) and the University of York for supporting this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Continuous hyperpolarization experiments were conceived and performed by J.B.H., implemented with the help of N.S. and T.L. N.S. performed the Earth-field MRI, which was provided by J.G.K. R.E.M. synthesized the Ir(IMes)(cod)Cl and L.A.R.H. and S.M.K. completed the adenine and adenosine SABRE experiments. Technical support was obtained by D.vE. and J.D.K. J.H. and D.vE. provided conceptual advice of the experiments. J.H., D.L., D.vE., J.G.K., G.G.R.G. and S.B.D. supported and contributed to the evaluation and interpretation of results. The manuscript was written by J.B.H. and edited by S.B.D., D.vE., J.H., D.L., J.G.K. and R.E.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S5 (PDF 328 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hövener, JB., Schwaderlapp, N., Lickert, T. et al. A hyperpolarized equilibrium for magnetic resonance. Nat Commun 4, 2946 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3946

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3946

This article is cited by

-

New Horizons in Hyperpolarized 13C MRI

Molecular Imaging and Biology (2023)

-

Quasi-continuous production of highly hyperpolarized carbon-13 contrast agents every 15 seconds within an MRI system

Communications Chemistry (2022)

-

Parahydrogen-induced polarization and spin order transfer in ethyl pyruvate at high magnetic fields

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Hydrogenative-PHIP polarized metabolites for biological studies

Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine (2021)

-

Unveiling coherently driven hyperpolarization dynamics in signal amplification by reversible exchange

Nature Communications (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.