Abstract

Recently, the anomalous photovoltaic (PV) effect in BiFeO3 (BFO) thin films, which resulted in open circuit voltages (Voc) considerably larger than the band gap of the material, has generated a revival of the entire field of photoferroelectrics. Here, via temperature-dependent PV studies, we prove that the bulk photovoltaic (BPV) effect, which has been studied in the past for many non-centrosymmetric materials, is at the origin of the anomalous PV effect in BFO films. Moreover, we show that irrespective of the measurement geometry, Voc as high as 50 V can be achieved by controlling the conductivity of domain walls (DW). We also show that photoconductivity of the DW is markedly higher than in the bulk of BFO.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, the entire field of photoferroelectrics has been revitalized by reports of an abnormal photovoltaic (PV) effect in BiFeO3 (BFO) thin films1. The main characteristics of this abnormal PV effect are very large open circuit photovoltages (Voc) exceeding the band gap of the material. For instance, in high quality BFO thin films, Voc is several times larger than the band gap (~2.7 eV). However, reports on the PV effect in different BFO systems are rather contradictory. In a specific in-plane geometry of measuring electrodes with respect to the domain pattern, films with periodic ferroelectric/ferroelastic stripe domain patterns show Voc values above1 or below the band gap2. In the normal plane-parallel capacitor geometry, the measured Voc value has always been below the band gap values3,4. Single crystals show, or do not show, large Voc values depending on the source or perhaps the crystal growth details5,6,7. To the best of our knowledge, there is not yet any report of abnormal PV effect in BFO ceramics.

In the original report on the abnormal PV effect on epitaxial BFO films, it was shown that Voc values as large as 15 V can be obtained, but only in a specific geometry when the ferroelectric/ferroelastic domain walls (DW) are running parallel to the macroscopic electrodes. If the ferroelectric domains are perpendicular to the electrodes, there was no sizable PV effect, but only a photoconductive effect was detected1. This has led to the hypothesis that the abnormal PV effect in BFO originates solely in the DW by the following mechanism: the photogenerated electron-hole pairs within the domain wall are separated by the strong field existing in this region, whereas within the bulk of the domains, the carriers will strongly recombine. The separated electrons and holes will accumulate only at the DW, building in such a way a small voltage across each domain wall. These voltages, although in the mV range, will sum up over macroscopic distances leading to the large open circuit voltage8. The bulk photovoltaic (BPV) effect, which is known to exist in materials lacking inversion symmetry such as LiNbO3, BaTiO3 or Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 (refs 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14), was a priori ruled out.

Subsequent experiments have shown that generation and recombination of photogenerated carriers in BFO single crystals are primarily affected by the presence of shallow energy levels, and that DW are not having a major role in the corresponding PV effect. Moreover, the photoexcited carriers are generated across the entire crystal, the recombination of these carriers is rather uniform and it is not necessarily stronger within the domains compared with the vicinity of the DW5,15.

We show here that the abnormal PV effect in BFO thin films with open circuit voltages (Voc) as large as 50 V exists irrespective of the domain wall geometry and that the DW are having a rather different role than initially proposed. We confirm that the abnormal PV effect in BFO is due to the BPV effect, as recently predicted by ab initio calculations using the ‘shift currents’ concept, which have been able to predict the short-circuit photocurrent, viz. magnitude and even spectral features, demonstrating that these shift currents should dominate the BPV response in BFO16,17.

Results

Thin film fabrication

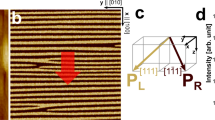

Nominally 100-nm thick (001)-oriented BFO epitaxial films were deposited by pulsed laser deposition on (110)-oriented TbScO3. Details on film growth and structure are given in the Methods section and Supplementary online Material (SOM) (Supplementary Figs S1–S3). Samples showing stripe domains comprising either 109° or 71° domain boundaries have been fabricated by choosing the growth conditions. In case of 109° domains, the stripes run along [100]c whereas in 71° domains, stripes run along the [010]c direction. Figure 1 shows the corresponding piezoforce microscope (PFM) images of the stripe domain pattern obtained on the thin films with 71° domains and a cross-sectional TEM image of a sample with dominant 109° domains.

PFM images (3.5 × 3.5 μm scan) of pristine sample with 71° domains, (a) out-of-plane phase image (b) in-plane phase image showing stripes, which run along [010]c. (c) Two-beam bright-field TEM image of a BFO epitaxial film grown on TbScO3 taken with near g=001c. The dark and bright contrasts show the domain structure of the BFO thin film. The type of domains was identified as 109° stripe domains with (100)c vertical DW. Scale bar, 100 nm. (d) The high-resolution TEM image corresponding to Fig. 1c shows coherency on either side of the vertical domain wall and the two polarization variants.

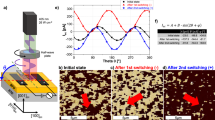

Platinum electrodes of 250 μm length and variable interelectrode distances (from 15 μm up to 100 μm) were fabricated by sputter deposition using conventional photolithography and lift-off technique. Devices were aligned parallel and perpendicular to the DW, as shown schematically in Fig. 2 (also Supplementary Fig. S4). The photoelectric effect was measured by illuminating the gap between the electrodes with a 405 nm (hυ= 3.06 eV) laser with a maximum power of 80 mW and simultaneously measuring the photocurrent using a high-input impedance electrometer.

Schematic showing the patterned electrodes on top of a film with majority 71° domains (not to scale) and typical measurement geometries in which the electrodes are running: (a) parallel (PLDW) and (b) perpendicular to DW (PPDW), respectively. The arrows indicate the direction of polarization in out-of-plane (up–down) and in-plane (left–right) directions.

Abnormal PV effect

To get a better insight into the actual mechanism of the abnormal PV effect in BFO, we have performed detailed photoelectric investigations on BFO epitaxial thin films with periodical domain patterns of 109° and 71° DW, respectively. At room temperature (RT) both geometries, parallel to the DW (PLDW) and perpendicular to the DW (PPDW), show PV behaviour similar to previous reports for 109° DW2. Current voltage (IV) characteristics under illumination shown in Fig. 3 reveal Voc values larger than the band gap of BFO (5 V for an interelectrode gap of 100 μm) in the PLDW geometry and nearly zero for the DW running perpendicular to the electrodes. Surprisingly, the BFO sample comprising 71° DW shows at RT a sizable Voc in both configurations, viz. −6.6 V perpendicular to the DW (PPDW) and − 7.6 V parallel to the DW (PLDW), as shown in Fig. 3b.

Temperature-dependent VOC

Photoelectric measurements were conducted at temperatures ranging from 80 to 450 K. By performing the analysis at different temperatures down to 80 K, we notice that in both geometries and DW variants by decreasing the temperature well below room temperature, the Voc values increase dramatically, that is, for 109° domains to more than 17 V and for 71° domains to more than 50 V, as shown in Fig. 4. The temperature dependence of Voc has a similar behaviour for both geometries; it increases at low temperature to values that are in both cases well above the band gap with an obvious increase at temperatures lower than 200 K. The most dramatic increase of Voc to about 20 times the bang gap is for 71° DW. For 109° domains in the PPDW geometry, the open circuit voltage, which at RT was almost zero, becomes at 83 K as large as 12 V. At RT, in the case of 71° domains in the PPDW geometry, where according to the initial model the open circuit voltage should be below the band gap, the Voc values are larger than 5 V. The sizable Voc in the perpendicular geometry in the case of 71° domains at RT and the dramatic increase of Voc with decreasing temperature in all cases suggest that those mechanisms in which the DW are at the origin of this effect, as it has been previously assumed1,8, are not valid and both bulk and DW should have a different role.

Bulk PV effect

Keeping in perspective the temperature-dependent behaviour of Voc, the only viable alternative explanation for the anomalous PV effect in BFO remains the BPV or photogalvanic effect, as known for materials lacking inversion symmetry, discovered by Chynoweth9 and later analysed theoretically by others18,19. Accordingly, under uniform illumination, the photocurrent Jph is due to an asymmetric generation in k-space, and under open circuit conditions, the open circuit voltage (Voc) is given by:

where ρ is the resistivity and L is the distance between the electrodes. Moreover, according to Fridkin13, Voc scales inverse proportionally with both dark conductivity and photoconductivity, so that equation (1) becomes:

where σd and σph are dark conductivity and photoconductivity, respectively.

The exponential-like increase of Voc with decreasing temperature is corroborated by the temperature variation of both dark conductivity and photoconductivity shown in Figure 5, which represents a direct proof of (1) and (2) for the case of BFO thin films.

As it can be easily seen, both dark and photoconductivity are higher in the case of 109° domains when compared with 71° domains. Also, both dark and photoconductivity are higher in the perpendicular than in the parallel geometry. These observations imply first that the DW have an enhanced conductivity and are largely governing both the dark and photoconductivity of the BFO films. This is not surprising, as the dc dark conductivity of 109° DW has been already estimated to be at least four orders of magnitude higher than the bulk of BFO20. In the same time, the conductivity of 71° DW is lower compared with the 109° DW, which is also in agreement to previous results21.

To explain the existence and/or absence of the abnormal PV effect and respectively a value of the open circuit voltage (Voc) larger than the band gap, we can assume that a photocurrent is rather uniformly generated in the entire film by the photogalvanic effect or, as recently shown using ab initio calculation, by so called ‘shift currents’16. In the same time the open circuit voltage is established according to (2) by the actual conductivity of the BFO film considering both the bulk and the domain wall conductivity. The effective sample conductivity is given by a simple equivalent circuit, which is either parallel or serial, depending on the geometrical arrangement of the collecting electrodes relative to the DW.

As schematically shown in Fig. 6, in the perpendicular geometry (PPDW), the equivalent circuit is a parallel circuit and the effective conductivity is given by the sum of both bulk and domain wall conductivities σtotal=(σbulk+σDW), whereas in the parallel geometry (PLDW), the appropriate equivalent circuit is the series circuit and in this case, the inverse of the effective conductivity is the sum of the inverse conductivities (σtotal)−1=(σbulk)−1+(σDW)−1.

A schematic showing the periodic arrangement of domains and DW in BFO thin films for the (a) parallel (PLDW) and (c) perpendicular (PPDW) geometry with respect to the DW. An equivalent circuit considering that the domain bulk and DW have different resistances, Rbulk and RDW, is shown for both the geometries in (b) PLDW and (d) PPDW.

According to this simple model, the effective resistance is lower when the DW are running perpendicular to the electrodes and thus, the open circuit voltage should be lower in the PPDW geometry. This is valid for all cases (see Fig. 5). For 109° domains in which the DW are much more conductive than in 71° domains, the Voc for all the cases was lower than what was measured in cases with 71° domains.

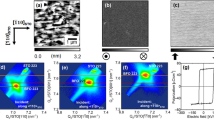

BPV effect in BFO films

In order to prove the existence of the bulk PV effect (BPV) in our films, we measured the PV current for all the systems by changing the angle between the plane of the linearly polarized light and the direction of current flow. The BPV effect has been studied extensively in non-centrosymmetric materials like KNbO3, BaTiO3, reduced LiTaO3, so on. The BPV effect in ferroelectrics can be expressed in the form of an equation given by14

where βijk is a third rank BPV tensor and I is the intensity of light. According to equation (3), when a homogenous ferroelectric crystal is illuminated uniformly by a linearly polarized light, it leads to the generation of a PV current  . The behaviour of this PV current in terms of its sign and magnitude depends on the orientation of the crystal with respect to the projections of the electric field of the linearly polarized light onto the plane of the sample along X and Y directions, namely

. The behaviour of this PV current in terms of its sign and magnitude depends on the orientation of the crystal with respect to the projections of the electric field of the linearly polarized light onto the plane of the sample along X and Y directions, namely  and

and  . Based on equation (3), and as detailed in the Methods, the current generated along the two orthogonal directions X and Y with the light propagating along the Z direction is given by14,22,23,24

. Based on equation (3), and as detailed in the Methods, the current generated along the two orthogonal directions X and Y with the light propagating along the Z direction is given by14,22,23,24

Figure 7a depicts the arrangement of the setup in which the coordinate system shown follows the pseudo-cubic notation of the BFO film so that the direction X is given by [100], Y is given by [010] and Z is given by [001]. The light illumination is along the Z [001] direction. For these measurements, the angle θ=0° means that the E vector of the linearly polarized light is parallel to the direction of the current flow, whereas an angle of 90° means that E is perpendicular to the current flow direction. The normalized values for the measured PV current by varying the angle between the current direction and the polarization axis of the light are presented in Fig. 7b.

(a) Schematic of a sample showing stripes, which represent the DW either of the 109° or 71° stripe domain system. The coordinate system is given by XYZ. The schematic shows how the vector E of the linearly polarized light is aligned with the direction of the current flow J for the PLDW case. (b) Normalized PV current measured at different angles (θ), which the polarization axis of the linearly polarized light makes with the direction of the current flow in the PLDW geometry for samples with 71° (circle) and 109° (triangle) domains, respectively. The solid line represents the fit with equation (4). PV current measured and predicted by varying the angle θ that the light polarization axis makes with the direction of current flow in c) PLDW geometry and d) PPDW geometry for a film consisting of 71° domains. In all, the plots a 5% (rough estimate) error has been incorporated in the PV current measurement to compensate for any misalignment in laser beam spot positioning.

It is rather evident from the plot shown in Fig. 7b that in either of the systems there is a definitive angular dependency exhibited by the PV current. For both systems studied, the normalized PV current fits the cosine function in (4) proving in this way that the origin of the PV current is the photogalvanic effect. However, we must take into consideration that equation (4) is calculated for rhombohedral symmetry. Therefore, in order to predict the exact response, which we obtain in lab coordinates, the BPV tensor must be transformed from rhombohedral to lab coordinates. We have performed this transformation for 71° domains. The details of this transformation are discussed in the Methods section. The net response obtained in the PLDW geometry can be expressed as

flowing in the direction of both ferroelastic distortion and polarization, which is consistent with the theoretical results16.

Similarly, the response in PPDW geometry can be expressed according to the equation

From equation (5), we can observe that the current collected in PLDW geometry is composed of two components. The second term due to the BPV effect has a cosine dependency and will oscillate depending on angle θ. The first term is also due to the BPV effect but is independent of angle θ. This is also evident when we fit equation (5) to the data we measured in the PLDW geometry as shown in Fig. 7c. The θ-dependent behaviour of the BPV current is shifted by the non-oscillating first term of equation (5). The current in PPDW geometry has a sine dependency on angle θ. However, in order to compensate for the combined effects of factors such as misalignments between the electrodes and domains and a misalignment between the light beam direction and the normal to the sample surface, we have introduced a phase shift θ0 and a constant current J0 to equation (6), which now can be expressed as:

From Fig. 7d, the agreement between the measured and predicted values from equation (7) is obvious. Based on equations (5, 6, 7) and the reported value of β22, we calculated the values of all the BPV coefficients, which are as follows β15=−7.1045 × 10−5 V−1, β31=−1.17 × 10−4 V−1 and β33=9.74 × 10−5 V−1. Corresponding values of the glass coefficients are G15=−3.946 × 10−10 cm V−1, G31=−6.5 × 10−10 cm V−1 and G33=5.41 × 10−10 cm V−1.

Discussion

We can now explain the scattered behaviour in the literature. The most important parameter seems to be the intrinsic conductivity. Samples in any form with high intrinsic conductivity should not show a large Voc. The high conductivity in BFO is a well-known problem, which might be the result of either unintentional doping of the raw material, or high oxygen vacancy density or any other fabrication parameter. Therefore, only the simple PV measurement at RT is not sufficient to conclude if a certain material exhibits the anomalous PV effect or not. A detailed complementary analysis of both dark conductivity and photoconductivity, including the temperature analysis and the spectral distribution of the latter (see Supplementary Figs S6 and S7), should be performed. In a thin film capacitor (plane-parallel) geometry, the film thickness is the most important parameter, as the open circuit voltage scales, according to equation (1), linearly with it. We would expect to obtain an open circuit voltage of about 0.6 Vμm−1 for the very favourable case shown in Fig 2a. Thus, to obtain a Voc larger than 3 V, the film thickness should be in the range of 5 μm. A large Voc in this geometry is not to be expected for usual sub-micron thicknesses. For a ceramic system, as the conductivity is extrinsic and usually through a grain boundary conduction mechanism, the value of Voc might depend tremendously on the effective fabrication process.

Coming back to the role of the DW in the PV in BFO, we can state that the DW, due to their intrinsically higher conductivity, are rather detrimental for the abnormal PV effect. In normal cases and at room temperature, the only geometry, which allows high Voc values is that with the DW running parallel to the collecting electrodes. If the DW are contacting the two collecting electrodes, as in the perpendicular geometry, the expected Voc values are low, as the DW are acting rather as shunts. Nevertheless, the DW proved to show a markedly higher photoconductivity than the domain bulk. This means that the density of the non-equilibrium carriers generated at the DW is much higher than in the bulk, and this might be more significant for photoelectric devices based on BFO than the value of the open circuit voltage.

In summary, by investigating the PV properties of BFO thin films in the low temperature range, it was observed that above-band-gap Voc (as large as 50 V) can be obtained irrespective of the domain wall geometry and the type of the domain wall. The Voc in all the samples and measurement geometries scaled up roughly exponentially with a decrease of temperature. The photogalvanic effect or the shift currents are at the origin of the abnormal PV effect in BFO. The high dark and photoconductivities of the DW are preventing a large open circuit voltage when these are connecting the collecting electrodes.

Methods

Film growth

Epitaxial BFO films of ~100 nm thickness were fabricated by pulsed laser deposition (PLD) technique. The films were deposited on orthorhombic TbScO3 (110) oriented substrates at 650 °C with oxygen pressure of 0.145 mbar. The laser energy was 0.35 J cm−2 and the laser repetition rate was kept at 5 Hz. To fabricate films with 109° domains, the deposition was performed on bare TbScO3 substrates. For obtaining 71° domains, the substrates were annealed in a tube furnace at 950 °C for 2 h along with an oxygen flow of ~200 sccm1,25.

Piezoforce microscopy

PFM was performed using a.c. excitation signal of 4 V amplitude and 33 kHz frequency applied on the AFM tip. AFM tips with Pt/Ti conductive coating and elastic constants of about 2 Nm−1 (NSC14, μMasch) were used.

Photoelectric measurements

The photoelectric effect was measured by illuminating the gap between the electrodes with a 405 nm (hυ=3.06 eV) laser (Newport LQA405-85E) with a maximum power of 80 mW and simultaneously measuring the photocurrent using a high-input impedance electrometer (Keithley 6517). Variable temperature measurements were performed using an optical cryostat (Janis VPF-700). Open circuit voltage was extracted from the current voltage characteristics.

BPV effect in ferroelectric materials

BFO belongs to the space group R3c and many of the 27 elements of the third rank tensor will be reduced to zero owing to symmetry operations26,27,28,29. The tensor thereafter can be contracted into a 3 × 6 matrix of the form

The incident light propagating along the Z-axis can be expressed as28,29

The electric field vector E of the light can be resolved into two components along X and Y axes having cosθ and sinθ dependencies, respectively.

Hence,

where θ is the angle, which the polarization axis makes with the direction of current flow. As E is a second rank tensor, it can be expressed in the form of a 6 × 1 matrix and equation (3) takes the form26,28:

From (11) we can approximate

and

and

Calculation of PV response

The BPV tensor βijk is a tensor of third rank. This means it has 33 elements. These elements can be expressed as:

As the projections of the electric field vector of the light (ejek) are symmetric with respect to each other, it means that the BPV tensor can be assumed to be symmetrical in j and k27,29. Due to this symmetry aspect, there remain only 18 independent  coefficients, which can be conveniently represented in a matrix notation of the form:

coefficients, which can be conveniently represented in a matrix notation of the form:

The coefficients in equation (12) are related to the coefficients in equation (13) in such an arrangement that the first suffix remains the same in both the notations, whereas the last two notations are related according to the relations presented in Table 1 (ref. 27):

However, there is a further reduction in the number of independent tensor coefficients due to the R3c symmetry of BFO. Henceforth, the matrix in equation (7) is reduced to27,28:

It can be observed by comparing equation (13) and (14) that, β22=−β21=−β16, β15=β24 and β31=β32 (ref. 27). Therefore, the BPV effect in BFO can be completely described by the help of four independent coefficients, which are β15, β22, β31 and β33. By using equation (14) and the matrix notations, we know that

Based on the relations given in (15), we can rewrite equation (12) to obtain a third rank tensor, which would be valid for BFO:

In order to predict the PV current, which we measure in lab coordinates, we must convert the BPV tensor from rhombohedral to lab coordinates. In addition, a film comprising of 71° domains, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S5, consists of two kinds of rhombohedral unit cells, which results in two different domains. These have been shown as R-type and L-type in Supplementary Fig. S5.

Therefore, such a conversion must be performed for both the cells and domains. The matrices, which are required to transform the rhombohedral coordinate system of the R-and L-type domains to lab coordinates are given by16:

The BPV tensor in the lab coordinates can then be expressed as a resultant of both the conversions:

Based on the non-zero terms in equation (16), we can elaborate equation (19) as:

From the relations given in (15) we can rearrange equation (20) to

Having calculated the BPV tensor in lab coordinates, we can now predict the PV current in lab coordinates by

The projections of the electric field of a linearly polarized light can be resolved into a second rank tensor via Jones matrix notation. This matrix can then be written in a (6 × 1) form of the type  . Also, as explained previously, we can reduce the lab BPV tensor (Bqrs) to a matrix notation of (3 × 6) type. Therefore, we can solve equation (22) by simple matrix multiplication with the result being of the type:

. Also, as explained previously, we can reduce the lab BPV tensor (Bqrs) to a matrix notation of (3 × 6) type. Therefore, we can solve equation (22) by simple matrix multiplication with the result being of the type:

As can be observed from equation (23), the main coefficients required to predict the PV current in PPDW and PLDW geometries are B12, B16, B11, B22, B26, B21. By substituting the values from equation (17) and (18) (using relation given in 15) into equation (21) we can calculate these terms to be:

By substituting the values of the coefficients from equation (24)–(29), in equation (23), the calculated PV current in the parallel measurement geometry is

Equation (30) can be further simplified by applying trigonometric operations resulting in

The calculated PV current in the perpendicular measurement geometry is

Additional information

How to cite this article: Bhatnagar, A. et al. Role of domain walls in the abnormal photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3. Nat. Commun. 4:2835 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3835 (2013).

References

Yang, S. Y. et al. Above-bandgap voltages from ferroelectric photovoltaic devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 143–147 (2010).

Guo, R., You, L., Chen, L., Wu, D. & Wang, J. Photovoltaic property of BiFeO3 thin films with 109° domains. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 122902 (2011).

Yang, S. Y. et al. Photovoltaic effects in BiFeO3 . Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 062909 (2009).

Lee, D. et al. Polarity control of carrier injection at ferroelectric/metal interfaces for electrically switchable diode and photovoltaic effects. Phys. Rev. B. 84, 125305 (2011).

Alexe, M. & Hesse, D. Tip-enhanced photovoltaic effects in bismuth ferrite. Nat. Commun. 2, 256 (2011).

Choi, T., Lee, S., Choi, Y. J., Kiryukhin, V. & Cheong, S.-W. Switchable ferroelectric diode and photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3 . Science 324, 63–66 (2009).

Moubah, R. et al. Photoelectric effects in single domain BiFeO3 crystals. Adv. Funct Mater. 22, 4814–4818 (2012).

Seidel, J. et al. Efficient photovoltaic current generation at ferroelectric domain walls. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 126805 (2011).

Chynoweth, A. G. Surface space-charge layers in Barium Titanate. Phys. Rev. 102, 705–714 (1956).

Koch, W. T. H. et al. Bulk photovoltaic effect in BaTiO3 . Solid State Comm. 17, 847–850 (1975).

Koch, W. T. H. et al. Anomalous photo voltage in BaTiO3 . Ferroelectrics 13, 305–307 (1975).

Glass, A. M., Linde, D. von der & Negran, T. J. High-voltage bulk photovoltaic effect and the photorefractive process in LiNbO3 . Appl. Phys Lett. 25, 233–235 (1974).

Fridkin, V. M. Photoferroelectrics Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, (1979).

Sturman, B. I. & Fridkin, V. M. The Photovoltaic and Photorefractive Effects in Noncentrosymmetric Materials Gordon and Breach Science (1992).

Alexe, M. Local mapping of generation and recombination lifetime in BiFeO3 single crystals by scanning probe photoinduced transient spectroscopy. Nano. Lett. 12, 2193–2198 (2012).

Young, S. M., Zheng, F. & Rappe, A. M. First-principles calculation of the bulk photovoltaic effect in Bismuth Ferrite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 236601 (2012).

von Baltz, R. & Kraut, W. Theory of the bulk photovoltaic effect in pure crystals. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5590–5596 (1981).

Belinicher, V. I. & Sturman, B. I. The photogalvanic effect in media lacking a center of symmetry. Sov. Phys. Usp. 23, 199–223 (1980).

Ruppel, W., von, Baltz R & Würfel, P. The origin of the photo-EMF in ferroelectric and non-ferroelectric materials. Ferroelectrics 43, 109–123 (1982).

He, Q. et al. Magnetotransport at domain walls in BiFeO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 067203 (2012).

Chiu, Y.-P. et al. Atomic-scale evolution of local electronic structure across multiferroic domain walls. Adv. Mater. 23, 1530–1534 (2011).

Ji, W., Yao, K. & Liang, Y. C. Evidence of bulk photovoltaic effect and large tensor coefficient in ferroelectric BiFeO3 thin films. Phys. Rev. B 84, 094115 (2011).

Festl, H. G., Hertel, P., Krätzig, E. & von Baltz, R. Investigations of the photovoltaic tensor in doped LiNbO3 . Physica Status Solidi (B) 113, 157–164 (1982).

Avakyan, E. M., Belabaev, K. G., Odulov, S. G. & Oleinik, O. I. Photogalvanic currents in reduced lithium-titanate crystals. Izvestiya Akademii Nauk SSSR. Seriya Fizicheskaya 47, 656–659 (1983).

Johann, F., Morelli, A. & Vrejoiu, I. Stability of 71° stripe domains in epitaxial BiFeO3 films upon repeated electrical switching. Physica Status Solidi (B) 249, 2278–2286 (2012).

Wilson, D. W., Glytsis, E. N., Hartman, N. F. & Gaylord, T. K. Beam diameter threshold for polarization conversion photoinduced by spatially oscillating bulk photovoltaic currents in LiNbO3: Fe. J. Optic. Soc. Am. B 9, 1714–1725 (1992).

Nye, J. F. Physical Properties Of Crystals Oxford University Press (1960).

Newnham, R. E. Properties Of Materials Oxford University Press (2005).

Weis, R. S. & Gaylord, T. K. Lithium niobate: summary of physical properties and crystal structure. Appl. Phys. A. 37, 191–203 (1985).

Acknowledgements

The work was partly funded by DFG via SFB 762. A.B. is thankful to IMPRS (International Max Planck Research School, Halle, Germany) for the funding and support. A.R.C. acknowledges the funding from Alexander von Humboldt foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. and A.B. designed and conceived the experiments. A.B. was responsible for thin film growth, PFM analysis and photoelectric measurements. A.R.C. participated in thin film growth. Y.H.K. carried out TEM investigations. M.A., A.B. and D.H. co-wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S7 and Supplementary Reference (PDF 1138 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bhatnagar, A., Roy Chaudhuri, A., Heon Kim, Y. et al. Role of domain walls in the abnormal photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3. Nat Commun 4, 2835 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3835

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3835

This article is cited by

-

Peculiar band geometry induced giant shift current in ferroelectric SnTe monolayer

npj Computational Materials (2024)

-

Light-induced giant enhancement of nonreciprocal transport at KTaO3-based interfaces

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Suppressing non-radiative recombination in metal halide perovskite solar cells by synergistic effect of ferroelasticity

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Giant bulk piezophotovoltaic effect in 3R-MoS2

Nature Nanotechnology (2023)

-

Effect of composition on magnetic and photoelectric properties of BiFeO3/CoFe2O4 thin films

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.