Abstract

Dissolution and migration of manganese from cathode lead to severe capacity fading of lithium manganate–carbon cells. Overcoming this major problem requires a better understanding of the mechanisms of manganese dissolution, migration and deposition. Here we apply a variety of advanced analytical methods to study lithium manganate cathodes that are cycled with different anodes. We show that the oxidation state of manganese deposited on the anodes is +2, which differs from the results reported earlier. Our results also indicate that a metathesis reaction between Mn(II) and some species on the solid–electrolyte interphase takes place during the deposition of Mn(II) on the anodes, rather than a reduction reaction that leads to the formation of metallic Mn, as speculated in earlier studies. The concentration of Mn deposited on the anode gradually increases with cycles; this trend is well correlated with the anodes rising impedance and capacity fading of the cell.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinel LiMn2O4 (LMO) has been considered as one of the most attractive cathode materials for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries in many respects, such as low cost, thermal safety and excellent rate capability1,2,3. The electrochemical reactions in these rechargeable batteries are based on the reversible insertion and extraction of lithium ions between active materials of the LMO cathode and carbon anode4. Along with these reversible reactions, however, dissolution and migration of manganese species from cathode to anode often occur and are generally attributed to HF acid generated by fluorine from fluorinated anion (PF6−) and protons from water impurities.5 This irreversible process is believed to be associated with the severe capacity fading of the cells, in particular, when the cells are operated at elevated temperatures (>55 °C). In fact, the migration of transition metals from other cathode materials has also been observed—for instance, LiFePO4 (ref. 6) and LixNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 (NCM)7—which likely leads to capacity fading of the batteries, especially during the aging process. Overcoming this major problem requires a better understanding of mechanisms of manganese dissolution, migration and deposition (DMD) on the anode.

In the past, researchers have proposed a mechanism to interpret the DMD process for manganese-based cathodes, which can be briefly described in the following three steps: a disproportionation reaction of Mn(III) in LiMn2O4 takes place at the interface of the cathode and electrolyte, as shown in equation (1)3,5,8,9,10,11,12,13,14

Consequently, Mn4+ remains on the cathode surface because of its insolubility in the electrolyte, whereas Mn2+ dissolves into the electrolyte; the dissolved Mn2+ species diffuse and migrate from the cathode to the anode. The Mn2+ species are finally reduced to metallic Mn on the anode surface. The third step is based on the speculation in literatures that the lithiated anode has low chemical potential and high chemical activity15,16,17,18,19. Although there are a few studies that reported Mn2+/Mn3+ being deposited on the graphite anodes on the basis of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements, these authors claimed that Mn was deposited as metal first (by reduction) and then oxidized to Mn(II)20,21, similar to the third step described above. Nevertheless, as a consequence of the manganese DMD process, the loss of active material (Mn3+) and the formation of inactive spinel on the cathode surface because of the disproportionation reaction increases the impedance of the cathode11,22. The solid–electrolyte interphase (SEI) at the anode is also poisoned because of the deposition of Mn (as metal) on the electrode surface15,16,23. Both aspects were believed to directly contribute to the capacity fading of the cell.

However, as characterization tools are not yet able to detect the extremely low concentration of manganese in the electrolyte and, in particular, on the anode, there is not yet much detailed evidence to pinpoint the exact nature of the reaction at the anode surface. Thus, there has been considerable speculation about the reactions at the anode surface. For instance, it has been speculated that Mn was reduced and deposited on the graphite anode as metallic Mn, as stated earlier, which consequently catalysed the decomposition of the electrolyte16 and/or modified the SEI to produce a high-impedance layer on the surface of the carbon anode23. This conclusion was mainly based on the finding that the potential of the lithium-intercalated graphite anode (<0.3 V versus Li/Li+) is much lower than the standard redox potential of Mn(II)/Mn (1.87 V versus Li/Li+). As a result, Mn(II) may be electrochemically reduced by the low anode potential16 or chemically reduced by lithiated graphite23. Although energy-dispersive spectroscopy15, dynamic secondary ion mass spectrometry24 and atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS)25 have proven the deposition of manganese species on anodes, conclusive identification of the oxidation state of Mn deposited on anodes remains a big challenge, which needs to be addressed in order to fully understand the reaction mechanism at the anode surface and, as a consequence, the capacity fading of the batteries.

Here we apply several advanced characterization techniques to conclusively identify the oxidation state of manganese deposited on the anode surface. We are able to clearly demonstrate by using X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) along with XPS that, surprisingly, the oxidation state of manganese deposited on the anodes is +2, which differs from most results reported earlier. The concentration of Mn deposited on the anode is found to increase gradually with increased cycles; moreover, this trend is well correlated with the anodes’ rising impedance. This work helps us to better understand the correlation between the manganese DMD process and capacity fading in Mn-based lithium-ion batteries and sheds some light on how to improve the cell performance.

Results

Electrochemical performance and manganese deposition

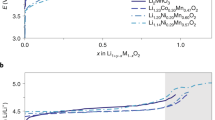

To determine the amount of manganese deposited on the anode, a Li/LMO half-cell was tested at a C/2 rate cycled between 3.5 and 4.3 V at room temperature. Figure 1a shows the normalized capacity versus cycle number for the Li/LMO cell. The data clearly indicate that the cell capacity is continuously fading to about 85% of initial value after 100 cycles in agreement with previously reported data for similar materials26. The concentrations of Mn deposited on the Li anodes after different cycles were measured using ICP-AAS (inductively coupled plasma-atomic absorption spectrometry), and the results are also presented in Fig. 1a. A significant amount of Mn (~85 p.p.m.) is already deposited on the anode after the formation cycles, and it gradually increases with the cycling. The concentration of Mn reaches up to about 400 p.p.m. after 100 cycles of charge and discharge. As reference, a fully assembled Li/LMO cell was stored under the same condition as that used when the other cells were cycled. No Mn is detected on the un-cycled Li anode, indicating that the DMD process does not occur in un-cycled cell. As the ICP-AAS analysis provides accurate results for Mn concentration deposited on the anode (because the lithium metal can be completely dissolved during the ICP-AAS measurement), we adopt these data as baseline to obtain Mn concentration on the other anodes using the fluorescence intensity of X-ray absorption near edge spectra (XANES), as presented later. Nevertheless, the half-cell results clearly suggest a correlation between manganese deposition on the anode and capacity fading in LMO-based cells.

Figure 1b compares the cycle performance of cells with LiMn2O4 cathodes versus different anodes with Li-insertion potentials ranging from 0 to 3.5 V (versus Li/Li+). The curves show that the LiMn2O4/Li4Ti5O12 (LTO) cell has almost no capacity fade after 100 cycles, and the LiMn2O4/delithiated LiFePO4 (D-LFP) cell loses about 5% capacity after 100 cycles. The curves also indicate that LiMn2O4 exhibits much poorer cycling performance when cycled against graphite, losing >15% capacity after 100 cycles. Characterization of Mn deposition on those anodes could help to better understand the difference in capacity-fading performance.

Oxidation state of Mn deposited on anodes

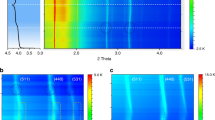

The Mn oxidation state on different anodes collected after 100 cycles was determined from XANES spectra recorded at room temperature. XANES reference spectra were recorded for Mn foil, MnO and Mn2O3 standards, as shown in Fig. 2a, whereas a more extensive collection of standard Mn spectra has been made available by Manceau et al.27 The edge position of XANES is typically used to determine the oxidation states of the element in the compound. On the basis of the XANES results shown in Fig. 2a and the standards available from Manceau et al.27, it is clear that the oxidation state of Mn deposited on all of the anodes used in this study is predominately +2. This result is surprising because it has been speculated in most of the earlier publications that Mn was reduced to metallic Mn state15,16,17,19,20,21. Moreover, our XANES data clearly suggest that the Mn oxidation state deposited on the anodes does not depend on their chemical potential and chemical activity during the discharge/charge process. In addition to the edge position, the fluorescence intensity of XANES can be used to determine the relative concentration of the tested element in the compound. The amount of Mn deposited on the selected anodes was calculated based on the Mn concentration on the Li anode from the ICP-AAS analysis and the fluorescence intensities in Fig. 2a. After the 100 cycle test, about 320 p.p.m. of Mn is deposited on the mesocarbon microbead (MCMB) anode, 260 p.p.m. on the D-LFP anode and 300 p.p.m. on the LTO anode compared with 400 p.p.m. on the Li anode as seen in Fig. 1a. Surprisingly, a large amount of Mn is deposited on the LTO and D-LFP anodes after 100 cycles. Figure 2b shows the XANES data for MCMB anodes collected after different cycles. The fluorescence intensity of the line at about 6,545 eV (1s→4p transition) increases systematically with increasing cycle number, indicating that Mn2+ species continue to deposit on the anode surface during the cycling tests.

Following the main edge, the X-ray absorption spectra show typical oscillations because of a scattering of the outgoing electron wave at the nearest-neighbour atoms. After a standard data treatment (background reduction, normalization, conversion to k and μ(0) fit), these waves yield the χ(k) function and the χ(k) × k2 function. The later function and its Fourier transform (FT) contain valuable information about the nearest-neighbour distances, the coordination number and the coordination geometry. Figure 3a shows the FT of the χ(k) × k2 functions of all investigated samples in R-space, where R is the Fourier conjugate to k, uncorrected for phase shifts, related to the distance to the nearest-neighbour shells. The positions of the peaks in the Fourier-transformed χ(k) × k2 functions depend on the real radius of the scattering shells around the X-ray-absorbing atoms (that is, Mn). The intensities of these peaks depend on the scattering amplitude, the coordination number and the Debye–Waller factor (σ2, the mean square disorder in the path lengths). Using feff (version 9)28 and ifeffit29 we have been able to fit the region of the FT from R=1–2.3 Å (k=2.75–10 Å−1, k2 weighting, modified Hanning windows with width 1 Å−1). A single Mn-O-scattering path suffices for three of the samples (D-LPF-100, LTO-100 and MCMB-100). For Li-100 a single scattering path no longer suffices, corresponding to the less distinct white line in the XANES spectrum (Fig. 2a). For the three samples, the Mn-O bond lengths are all within 2.15±0.03 Å. This bond length is slightly shorter than that for MnO (manganosite: RMn-O=2.222 Å) but is generally consistent with the range of Mn(II)-O bond lengths30.

To further study the anode surface, XPS measurements were performed on different anodes collected after 100 cycles. Unlike the XANES technique, XPS is more surface-sensitive (measured depth is about 1–3 nm); therefore, it is an ideal tool to analyse the SEI on the anodes31,32. The Mn 2p, Li 1s, C 1s, O 1s and F 1s XPS spectra were recorded and fitted. Figure 3b presents the Mn 2p core level XPS spectra of the MCMB, LTO and D-LFP anodes after 100 cycles. The analysis of Mn 2p XPS spectra of all the samples shows that Mn is deposited on the anodes as Mn2+, which is consistent with the XAS results discussed earlier. In addition, two more interesting features are noted from the Mn 2p XPS spectra. First, the Mn 2p3/2 peak slightly shifts to higher binding energy from MCMB to D-LFP to LTO, indicating that Mn is bonded to a more electron-negative element in LTO than in MCMB. In other words, the Mn-containing species that deposited on selective anodes are different, although they have the same oxidation state (+2). Second, according to the peak amplitudes, the MCMB anodes have less Mn deposited, whereas LTO has much more Mn deposited on the surface. As the SEI in LTO and MCMB are different, it is conceivable to expect that the products resulting from the reaction between these SEIs and dissolved Mn2+ in the electrolyte are different, as confirmed using XPS. Analysis of Li 1s, C 1s, O 1s and F 1s XPS spectra of all the samples did indicate that the SEI formed on various anodes is different (Supplementary Fig. S1).

From the XAS and XPS data presented above, we conclude that the oxidation state of Mn deposited on anodes is predominately +2, which is independent of the anode potentials. As far as we know, this is the first time that solid evidence has been provided for the identification of the Mn oxidation state during the Mn DMD process in LMO-based cells. It should be mentioned that there are a few studies that reported the observation of Mn2+/Mn3+ deposited on the carbon anode, especially in the papers of Komaba et al.20 and Ochida et al.21 However, they did not provide as conclusive results as we presented in this work on the oxidation state of Mn deposition in a real LMO/graphite cell, and especially on the correlation between the Mn deposition and capacity fade of the cell. First, significant amount (>100 p.p.m.) of Mn2+ was pre-added to the electrolyte in their studies either using Mn(ClO4)2 or introduced by anodic dissolution of Mn metal, which does not represent the real situation in the LMO/C cells in which the Mn2+ concentration in the electrolyte increases gradually from zero because of the dissolution of Mn from the LMO cathode. For instance, in the first discharge/charge cycle, the Mn2+ concentration in the electrolyte is lower than 5 p.p.m.8. Second, they believe that Mn2+ was deposited as metal first by reduction of the low-potential lithiated carbon and then re-oxidized to Mn(II) or Mn(III) subsequently by the electrolyte. In contrast, in our work, we found that the Mn deposition can occur on anodes with potential as high as 3.5 V (D-LFP anode) versus Li/Li+, and hence we believe that the Mn deposition was not a reduction reaction driven by the low potential of the anodes but an ion-exchange reaction (metathesis reaction) driven by the solubility of the species involved. This is further confirmed by the observation of Mn(II) on delithiated carbon electrode (with SEI formed on the surface) after simply immersing it in the electrolyte containing Mn(II) dissolved from LiMn2O4 powder (Supplementary Fig. S2). In addition, the SEI layer starts to form on the carbon anode during the first charge. Therefore, if Mn(II) in the electrolyte would be reduced on the carbon surface, it has to diffuse through the SEI layer to reach the carbon surface to be reduced by lithiated graphite particle, which is kinetically unfavourable. Therefore, metathesis reaction of Mn(II) with species in the SEI layer, which directly leads to the formation of Mn(II) on the anodes, most likely is the reaction that takes place on the anode surface during the Mn deposition, rather than a reduction reaction that leads to the formation of metallic Mn, as reported in most earlier studies15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. At this point, we are unable to pinpoint the exact metathesis reactions that occur on the anodes owing to the lack of knowledge of the composition of the SEI formed on the various anodes; however, we are able to propose the reaction mechanism based on the impedance results presented later. Nevertheless, it is clear from the XAS and XPS results that different Mn(II)-containing species deposit on the anodes during the Mn DMD process, which certainly depends on the nature of the SEI on the anodes.

Correlation between Mn deposition and capacity fading

Two questions remain: What is the correlation between the quantity of Mn deposited on anodes and the rate of capacity fading, especially in the graphite anode? How does the Mn2+ act in the SEI of the graphite anode? To address these issues, we first employed a simple calculation to estimate the capacity fading contributed solely from the loss of active materials in the cathode because of the DMD process. Both the amount of Mn deposited on the anodes (based on ICP-AAS and XAS data) and that dissolved in the electrolytes (based on literature data) were accounted for in the calculation. The calculated capacity fading in the MCMB-LMO cell resulting from the loss of active Mn3+ (<1%) is significantly smaller than the overall capacity fading determined experimentally from the 100-cycle data (15%). For the LTO-LMO and D-LFP-LMO cells, much less overall capacity fading is found, even with almost the same amount of Mn deposited on the anodes. This finding suggests that the capacity fading in the MCMB-LMO cell is not directly caused by the loss of the active Mn3+. A possible reason for the severe capacity fading in the MCMB-LMO cell is that Mn2+ in the electrolyte reacts with the SEI on the graphite anode, which modifies the nature of the SEI. As a result, the impedance of the graphite anode could change as the Mn2+ concentration increases in the SEI during the cycle test.

To understand the correlation between the reaction of Mn2+ in the electrolyte with the SEI and the impedance change of the graphite anode in the LiMn2O4-based cells, we first compared the AC impedance rise of graphite anodes (with SEI formed) stored in electrolyte with or without Mn2+ by using a three-electrode configuration. Graphite anodes were first cycled against Li metal for one cycle to form an SEI layer and then fully discharged to 5 mV versus Li/Li+. The fully discharged graphite anodes were disassembled and transferred to a three-electrode cell (with Li metal as counter electrodes and LixSn micro-reference electrode) filled with either a pure electrolyte or an electrolyte with 20 p.p.m. Mn2+. As shown in Fig. 4, the impedance of graphite anode does not change much when stored in the pure electrolyte but increases notably when stored in the electrolyte with Mn2+. This result clearly indicates that Mn2+ in the electrolyte reacts with the SEI on the graphite anode and modifies the nature of the SEI accordingly, leading to the increase in the impedance of graphite anode. It is also worthwhile to note that the impedance of graphite anode in the electrolyte with Mn2+ is stabilized after 24 h, likely because of the depletion of Mn2+ in the electrolyte.

In situ AC impedance spectroscopy in a three-electrode configuration was performed to probe the capacitive and resistive behaviour of the graphite anodes after different times of cycling against bare LMO at C/2 and 55 °C. For comparison, similar measurement was also performed on the graphite anode cycling against surface-modified LMO with TiO2, which is expected and confirmed with the ICP-AAS measurement (Supplementary Supplementary Table S1) to have much less Mn dissolved from the cathode during the cycling test. In other words, the dissolution of Mn is considerably suppressed from the surface-modified LMO. Figure 5 compares the cycle performance of cells with graphite anode versus bare LMO and surface-modified LMO cathodes. The curves indicate that bare LMO exhibits much poorer cycling performance when cycled against graphite at 55 °C, losing >50% capacity after 100 cycles, whereas only about 20% capacity loss is observed for the surface-modified LMO.

The AC impedance rise of the graphite anode and bare LMO cathode is shown in Fig. 6a,b, respectively. The cells were discharged to 50% state of charge (SOC) before each impedance testing. The impedance rise of the bare LMO cathode slows down after 25 cycles (Fig.6b), whereas that of the graphite anode increases significantly and contributes to almost all the increase in the impedance of the full cell after 50 cycles (Fig. 6a). Corroborating the capacity versus cycle number diagram for the MCMB-LMO cell shown in Fig. 5 and these impedance results, it appears that the impedance rise of the cathode is not responsible for the capacity loss. The trend of impedance rise from the anode matches that of the capacity loss during the cycling test, indicating that the anode impedance is the key factor that causes the capacity fading of the full cell. Figure 6c shows the AC impedance rise of the graphite anode cycling against surface-modified LMO at different cycles, which clearly indicates that the impedance of the graphite anode grows much slower than that of the graphite anode in the bare LMO cell (Fig. 6a). Similar results were also reported for MCMB-Li1.1[Ni1/3Mn1/3Co1/3]0.9O2 cells33. In addition, we also performed the same in situ AC impedance spectroscopy for the LTO anode after different times of cycling against bare LMO at C/2 rate (Supplementary Fig. S3). The impedance of the LTO anode grows much slower than that of the graphite anode in the bare LMO cell (Fig. 6a), corresponding to much slower capacity fading than the LTO/LMO cell (Fig. 1b). There is, thus, a strong correlation between impedance rise of the anode and the concentration of Mn2+ in the SEI on the graphite anode, as well as the capacity fading.

(a) The graphite anode and (b) bare LiMn2O4 cathode after different times of cycling at C/2 and 55 °C. (c) AC impedance rise of the graphite anode cycling against surface-modified LMO. (d) Plots of RSEICSEI of graphite anodes cycling against bare and surface-modified LMO at different cycles based on the fitting results in Supplementary Table S2.

Discussion

As assumed in earlier reports, Mn deposition could change the structure or composition of SEI on graphite anodes, resulting in the capacity fading of the full cell34. To elucidate the effect of Mn deposition on the electrochemical properties of the SEI layer, a detailed theoretical analysis of the anode impedance was performed, as described in the Supplementary Note 1. The fitting results (Supplementary Table S2) showed the increase of RSEICSEI, which indicates that the SEI layer on the graphite anode is not simply thickened but also undergoes change in its nature behaviour during cycling of the cell. On the basis of the fitting results in Supplementary Table S2, the change of RSEICSEI of graphite anodes cycling against both bare and surface-modified LMO cathodes is plotted in Fig. 6d. It is clearly seen that a dramatic increase in RSEICSEI of graphite anode was observed for the cell containing bare LMO, whereas a much smaller increase (by a magnitude of 2) in RSEICSEI of the graphite anode was observed for the cell containing surface-modified LMO. This is well correlated to their capacity fade, as shown in Fig. 5. According to the results presented above, we believe that the capacity fading is caused by changes in the SEI on the graphite anode because of the Mn2+ that continuously migrated from the cathode and thus the change of the impedance of the graphite anode.

Corroborating XANES/XPS and AC impedance results, we propose a metathesis reaction (ion exchange) mechanism for the Mn deposition on the carbon anode, as illustrated in Fig. 7. We believe that the ion exchange during the Mn deposition is between Mn2+ and mobile Li+ in the SEI—for example, lithium alkyl carbonate (ROCO2Li), which blocks the lithium diffusion path—and thus, leads to the increase in RSEICSEI of graphite anodes (Fig. 6d). This is also confirmed by the absence of MnF2 and MnCO3 on the SEI, which would result from the ion exchange between Mn2+ and the immobile Li+ in LiF and Li2CO3 on the SEI otherwise.

In summary, we demonstrated in this study that the oxidation state of manganese deposited on the anodes is +2 on the basis of XAS and XPS analyses. The results also suggest a metathesis reaction between Mn2+ and some species on the SEI during the deposition of Mn on the anodes, rather than a reduction reaction that leads to the formation of metallic Mn otherwise, as speculated in earlier studies. The capacity fading is caused by changing of the SEI on the graphite anode because of the continuous reaction with the dissolved Mn2+ from the cathode.

Methods

LiMn2O4 synthesis and characterization

Stoichiometric LiMn2O4 particles were synthesized via a solid-state method with Li2CO3 (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.0%) and chemical MnO2 (Chemetal, 99.5%), which were mixed and ground thoroughly in a molar ratio of 1.05: 4. The mixture was then heated at 800 °C for 16 h. The structure of the as-prepared spinel LiMn2O4 was confirmed using X-ray powder diffraction and scanning electron microscopy (Supplementary Supplementary Figs. S4–S6 and Supplementary Note S1). The surface-modified LiMn2O4 powders with TiO2 was prepared as follows: Tetrabutyl titanate (Sigma-Aldrich, 99%) was first dissolved in ethanol to make a 10% solution, and then the solution was slowly dropped into acetic acid solution (which contained 10% acetic acid and 56% ethanol) with agitation to obtain the sol, which was further diluted to 5% by adding ethanol to prevent the aggregation of the colloid. Then the LiMn2O4 powders were put into the diluted sol, agitated for 20 min, followed by drying at 80 °C and calcination at 750 °C for 4 h. The resulting molar ratio of TiO2:LiMn2O4 in the surface-modified LiMn2O4 is ~5%.

Electrochemistry tests

2032-type coin cells were assembled with a cathode material of 85% LiMn2O4, 10% carbon black and 5% polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) binder. The GenII electrolyte was composed of 1.2 M LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate: ethyl methyl carbonate at a 3:7 ratio by weight. Anodes with different Li-insertion potentials were tested, including 0 V (Li metal), 0.02 V (92% MCMB graphite and 8% PVDF), 1.55 V (80% Li4Ti5O12, 10% carbon black and 10% PVDF) and 3.5 V (85% LiFePO4, 10% carbon black and 5% PVDF, fully charged before being used as anode). If not otherwise specified, the cells were first cycled with a constant current of C/10. After the formation cycles, the cells were cycled at a constant current of C/2. Specific voltage windows (depending on the anode) were selected in order to charge and discharge the LiMn2O4 cathodes between 3.5 and 4.3 V (versus Li/Li+). The electrolyte with Mn2+ was prepared by soaking 0.1 g LiMn2O4 in 10 ml GenII electrolyte in a sealed container at 55 °C for 14 days. The concentration of Mn2+ in electrolyte was about 20 p.p.m. from the ICP-AAS analysis.

The AC impedance of cycled anodes and cathode was determined by using reference electrode cells, as described in detail elsewhere35,36,37. The test cell was assembled with flat, single-sided, 32-cm2 electrodes. A micro-reference electrode was prepared from a 25-μm-diameter copper wire coated with 1-μm-thick tin and covered with a polyurethane coating. The reference wire was shorted to the lithiated anode, which caused the transfer of some lithium from the anode to Sn to make a LixSn electrode. The reference electrode cells were first charged at a rate of C/10 and cycled between 3.0 and 4.3 V at C/2 before being constant-voltage-charged to 50% SOC. The AC impedance data for the anode and cathode were collected with a Solartron 1470 E and 1451A cell test system using a 5-mV AC perturbation with frequency ranging from 1 MHz to 20 MHz.

Characterization of Mn deposition

The disassembled anodes were rinsed with a mixture of ethylene carbonate/ethyl methyl carbonate (3:7 by weight) to remove the residual electrolyte remaining on the anode surface. To avoid any contamination to the surface, this procedure was carefully performed in an argon-filled glove box. Inductively coupled plasma (ICP) was applied to analyse the amount of Mn deposited on the Li metal anode, as Li can be thoroughly dissolved by acid and hence provide reliable Mn concentration.

The oxidation states of Mn deposited on anodes were characterized by using X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and XPS. For the XAS measurements, the samples are protected by Kapton tape to prevent the contamination from the air. Mn K-edge XAS measurements were conducted on both the bending magnet (10BM) and insertion device (10ID) beamlines of the Materials Research Collaborative Access Team in the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. Harmonic rejection was accomplished with an Rh-coated mirror. Anode spectra were measured on 10BM in the fluorescence mode using a four-element silicon drift detector (SII NanoTechnology USA Inc., Vortex-ME4). A third detector in the series simultaneously collected a metallic Mn reference spectrum with each measurement for energy calibration. The peak of the first derivative was set to 6,537.7 eV.

Samples were also analysed with XPS using a Kratos Axis Ultra DLD surface analysis instrument. The base pressure of the analysis chamber during these experiments was 3 × 10−10torr, with operating pressures around 1 × 10−9torr. Spectra were collected with a monochromatic Al Kα source (1,486.7 eV) and a 300 × 700-μ spot size. For survey spectra, the data were collected at a pass energy of 160 eV (fixed analyser transmission mode), a step size of 1 eV and a dwell time of 200 ms. High-resolution regional spectra were collected with a pass energy of 20 eV (fixed analyser transmission mode), a step size of 0.1 eV and a dwell time of 300 ms. For low signal-to-noise regions, multiple passes were made and the results were averaged together.

Prior to their introduction into the load-lock vacuum chamber of the XPS instrument, all air-sensitive samples were loaded into an inert transfer module interfaced with the instrument. Samples were prepared for analysis in an Ar-filled glove box, with no more than 1 p.p.m. O2 and 1 p.p.m. H2O. Nonconductive samples showed evidence of differential charging, resulting in peak shifts and broadening. Photoelectron peak positions were shifted back towards their true values, and their peak widths were minimized by flooding the samples with low-energy electrons and ions from the charge neutralizer system on the instrument. Peak position was further corrected by referencing the C 1s peak position of adventitious carbon for a sample (284.8 eV, PHI Handbook of Photoelectron Spectroscopy) and by shifting all other peaks in the spectrum accordingly.

Fitting was carried out by using the program CasaXPS. Peaks were fit as asymmetric Gaussian/Lorentzians, with 0–30% Lorentzian character. The full width at half maximum of all subpeaks was constrained to 0.7–2 eV, as dictated by instrumental parameters, lifetime broadening factors and broadening because of sample charging. With this native resolution set, peaks were added, and the best fit, using a least-square fitting routine, was obtained while adhering to the constraints mentioned above.

Analysis of impedance spectra

According to the model first reported by Thomas et al.38 and further improved by Barsoukov et al.39, we used the equivalent circuit (Supplementary Fig. S7) for interpreting our anode impedance spectra, where Rs is the resistance of the electrolyte, separator and wires; Rct and Cdl represent the charge transfer resistance and double-layer capacitance at the electron/ion conduction boundary for the Li-insertion reactions; RSEI and CSEI represent the resistance and the geometric capacitance of the SEI layer; and Zw is the Warburg diffusion impedance of the Li ion into the bulk particles via solid-phase diffusion.

As shown in Fig. 5a, the impedance of the graphite electrode typically includes two depressed semicircles in the high-frequency region and a line in the low-frequency region, which can be fitted to two serially connected parallel Rct elements and the Warburg element, respectively, in the equivalent circuit. The first semicircle (in higher-frequency region, as shown in the insertion of Fig. 5a) remains almost the same from the 25th to 100th cycle, whereas the second one (at lower-frequency region) enlarges constantly with the cycle time. As Rct and Cdl represent the Li-intercalation reaction impedance, which is mainly determined by intrinsic properties of the active material, electrode SOC and temperature, it is reasonable to assume that Rct and Cdl tested here remain constant with the cycling number. On the other hand, the SEI layer will get thicker with the cycling of the cell, thereby changing RSEI and CSEI. We, therefore, assigned the first semicircle to the RctCdl element and the second one to the RSEICSEI element. The fitting results are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The deviation of the spectra in the high-frequency region (inset to Fig. 5a) can be attributed to electron conduction and Li-ion diffusion in the porous electrode40.

According to the SEI model41, RSEI and CSEI can be calculated based on the following equations: RSEI=ρl/S and CSEI=εS/l, where ρ and ε are the specific resistance and permittivity of the layer, respectively, and l and S are the real electrochemically active thickness and area, respectively. The increase in RSEI and decrease in CSEI might be related to the thickening of the SEI layer, whereas ρ and ε could change with cycling as well. Therefore, RSEICSEI=ρε is selected here as a reliable value to indicate the intrinsic electrochemical properties of the SEI layer determined by its composition, although independent of its geometry. The fitting results showed the increase in RSEICSEI, which indicates that the SEI layer on the anode is not simply thickened but also undergoes change in its nature behaviour during cycling of the cell.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Zhan, C. et al. Mn(II) deposition on anodes and its effects on capacity fade in spinel lithium manganate–carbon systems. Nat. Commun. 4:2437 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3437 (2013).

References

Thackeray, M. M., David, W. I. F., Bruce, P. G. & Goodenough, J. B. Lithium insertion into manganese spinels. Mater. Res. Bull. 18, 461–472 (1983).

Guyomard, D. & Tarascon, J. M. Li metal-free rechargeable LiMn2O4/carbon cells their understanding and optimization. J. Electrochem. Soc. 139, 937–948 (1992).

Gummow, R. J., Dekock, A. & Thackeray, M. M. Improved capacity retention in rechargeable 4V lithium/lithium manganese oxide (spinel) cells. Solid State Ionics 69, 59–67 (1994).

Lazzari, M. & Scrosati, B. Cyclable lithium organic electrolyte cell based on 2 intercalation electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 127, 773–774 (1980).

Amatucci, G. G. et al. Materials’ effects on the elevated and room temperature performance of C/LiMn2O4 Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 69, 11–25 (1997).

Aurbach, D. et al. Review on electrode-electrolyte solution interactions, related to cathode materials for li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 165, 491–499 (2007).

Zheng, H., Sun, Q., Liu, G., Song, X. & Battaglia, V. S. Correlation between dissolution behavior and electrochemical cycling performance for LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 -based cells. J. Power Sources 207, 134–140 (2012).

Jang, D. H., Shin, Y. J. & Oh, S. M. Dissolution of spinel oxides and capacity losses in 4V Li/LiMn2O4 cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 143, 2204–2211 (1996).

Jang, D. H. & Oh, S. M. Electrolyte effects on spinel dissolution and cathodic capacity losses in 4V Li/LiMn2O4 rechargeable cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 3342–3348 (1997).

Xia, Y., Zhou, Y. & Yoshio, M. Capacity fading on cycling of 4V Li/LiMn2O4 cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 2593–2600 (1997).

Choa, J. & Thackeray, M. M. Structural changes of LiMn2O4 spinel electrodes during electrochemical cycling. J. Electrochem. Soc. 146, 3577–3581 (1999).

Gnanaraj, J. S., Pol, V. G., Gedanken, A. & Aurbach, D. Improving the high-temperature performance of LiMn2O4 spinel electrodes by coating the active mass with mgo via a sonochemical method. Electrochem. Commun. 5, 940–945 (2003).

Yu, L. H., Qiu, X. P., Xi, J. Y., Zhu, W. T. & Chen, L. Q. Enhanced high-potential and elevated-temperature cycling stability of LiMn2O4 cathode by TiO2 modification for Li-ion battery. Electrochim. Acta. 51, 6406–6411 (2006).

Walz, K. A. et al. Elevated temperature cycling stability and electrochemical impedance of LiMn2O4 cathodes with nanoporous ZrO2 and TiO2 coatings. J. Power Sources 195, 4943–4951 (2010).

Blyr, A. et al. Self-discharge of LiMn2O4/C Li-ion cells in their discharged state. J. Electrochem. Soc. 145, 194–209 (1998).

Komaba, S., Kumagai, N. & Kataoka, Y. Influence of manganese(II), cobalt(II), and nickel(II) additives in electrolyte on performance of graphite anode for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 47, 1229–1239 (2002).

Komaba, S., Itabashi, T., Kaplan, B., Groult, H. & Kumagai, N. Enhancement of Li-ion battery performance of graphite anode by sodium ion as an electrolyte additive. Electrochem. Commun. 5, 962–966 (2003).

Komaba, S. et al. Inorganic electrolyte additives to suppress the degradation of graphite anodes by dissolved Mn(II) for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 119-121, 378–382 (2003).

Whittingham, M. S. Lithium batteries and cathode materials. Chem. Rev. 104, 4271–4301 (2004).

Komaba, S. et al. Impact of 2-Vinylpyridine as electrolyte additive on surface and electrochemistry of graphite for C/LiMn2O4 Li-Ion Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 152, A937–A946 (2005).

Ochida, M. et al. Influence of manganese dissolution on the degradation of surface films on edge plane graphite negative-electrodes in Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 159, A961–A966 (2012).

Hirayama, M. et al. Dynamic structural changes at LiMn2O4/electrolyte interface during lithium battery reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 15268–15276 (2010).

Amine, K. et al. Improved lithium manganese oxide spinel/graphite Li-ion cells for high-power applications. J. Power Sources 129, 14–19 (2004).

Abraham, D. P., Spila, T., Furczon, M. M. & Sammann, E. Evidence of transition-metal accumulation on aged graphite anodes by SIMS. Electrochem. Solid State 11, A226–A228 (2008).

Tsunekawa, H. et al. Capacity fading of graphite electrodes due to the deposition of manganese ions on them in Li-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 149, A1326–A1331 (2002).

Sun, Y.-K., Hong, K.-J. & Prakash, J. The effect of ZnO coating on electrochemical cycling behavior of spinel LiMn2O4 cathode materials at elevated temperature. J. Electrochem. Soc. 150, A970–A972 (2003).

Manceau, A., Marcus, M. A. & Grangeon, S. Determination of Mn valence states in mixed-valent manganates by XANES spectroscopy. Am. Mineral. 97, 816–827 (2012).

Rehr, J. J. & Albers, R. C. Theoretical approaches to X-ray absorption fine structure. Rev. Mod. Phys. 72, 621–654 (2000).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. Athena, artemis, hephaestus: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using ifeffit. J. Synchrotron. Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Pacalo, R. E. & Graham, E. K. Pressure and temperature-dependence of the elastic properties of synthetic MnO. Phys. Chem. Miner. 18, 69–80 (1991).

Peled, E. et al. Composition, depth profiles and lateral distribution of materials in the SEI built on HOPG-TOF SIMS and XPS studies. J. Power Sources 97-98, 52–57 (2001).

Aurbach, D. et al. Recent studies on the correlation between surface chemistry, morphology, three-dimensional structures and performance of Li and Li-C intercalation anodes in several important electrolyte systems. J. Power Sources 81-82, 91–98 (1997).

Amine, K. et al. Mechanism of capacity fade of MCMB/Li1.1(Ni1/3Mn1/3Co1/3)0.9O2 cell at elevated temperature and additives to improve its cycle life. J. Mater. Chem 21, 17754–17759 (2011).

Amatucci, G., Du Pasquier, A., Blyr, A., Zheng, T. & Tarascon, J. M. The elevated temperature performance of the LiMn2O4/C system: failure and solutions. Electrochim. Acta. 45, 255–271 (1999).

Abraham, D. P., Poppen, S. D., Jansen, A. N., Liu, J. & Dees, D. W. Application of a lithium-tin reference electrode to determine electrode contributions to impedance rise in high-power lithium-ion cells. Electrochim. Acta. 49, 4763–4775 (2004).

Jansen, A. N., Dee, D. W., Abraham, D. P., Amine, K. & Henriksen, G. L. Low-temperature study of lithium-ion cells using a LiySn micro-reference electrode. J. Power Sources 174, 372–379 (2007).

Dee, D. W., Jansen, A. N. & Abraham, D. P. Theoretical examination of reference electrodes for Li-ion cells. J. Power Sources 174, 1001–1006 (2007).

Thomas, M. G. S. R., Bruce, P. G. & Goodenough, J. B. AC impedance analysis of polycrystalline insertion electrodes: application to Li1-xCoO2 . J. Electrochem. Soc. 132, 1521–1528 (1985).

Barsoukov, E., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. H., Yoon, C. O. & Lee, H. Kinetics of lithium intercalation into carbon anodes: in situ impedance investigation of thickness and potential dependence. Solid State Ionics 116, 249–261 (1999).

Barsoukov, E. & Macdonald, J. R. Impedance Spectroscopy: Theory, Experiment, and Applications 2nd edn Blackwell Science Public, Osney Mead (2005).

Peled, E., Golodnitsky, D., Ardel, G. & Eshkenazy, V. The SEI model - application to lithium polymer electrolyte batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 40, 2197–2204 (1995).

Acknowledgements

J.L. was supported by the Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) Postdoctoral Research Award under the EERE Vehicles Technology Program administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) for the DOE managed by Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU) under DOE contract number DE-AC05-06OR23100. K.A. and A.J.K. (X-ray absorption studies) were supported by the Center for Electrical Energy Storage, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. A.N.J. was supported by the Applied Battery Research for Transportation (ABR) Program from the U.S. DOE-EERE Office of Vehicle Technologies. Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for DOE, Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. MRCAT operations are supported by the DOE and the MRCAT member institutions. Financial support from the 973 Program (2009CB220105) of China, Beijing Natural Science Foundation (2120001), National Natural Science Foundation of China (21273129) and Bosch (China) Ltd. is gratefully acknowledged. This work was also supported by the Human Resources Development of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant funded by the Korean government, Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (No. 20124010203310) and by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (No. 2009-0092780).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. designed the experiments; C.Z. synthesized the cathode materials, performed and analysed the electrochemical experiments, A.J.K., J.L. and T.W. performed and analysed the X-ray absorption spectroscopy measurements; J.L. performed and analysed the XPS experiments; A.N.J. fabricated the three-electrode cells for impedance measurements; X.Q. and K.A. supervised the project; J.L., C.Z. and K.A. wrote the paper. All of the authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S7, Supplementary Tables S1-S2 and Supplementary Note 1 (PDF 401 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhan, C., Lu, J., Jeremy Kropf, A. et al. Mn(II) deposition on anodes and its effects on capacity fade in spinel lithium manganate–carbon systems. Nat Commun 4, 2437 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3437

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3437

This article is cited by

-

Recent Advances in Electrolytes for High-Voltage Cathodes of Lithium-Ion Batteries

Transactions of Tianjin University (2023)

-

Crossover effects of transition metal ions in high-voltage lithium metal batteries

Nano Research (2023)

-

A medium-entropy transition metal oxide cathode for high-capacity lithium metal batteries

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Core-shell structure of LiMn2O4 cathode material reduces phase transition and Mn dissolution in Li-ion batteries

Communications Chemistry (2022)

-

Inorganic Colloidal Electrolyte for Highly Robust Zinc-Ion Batteries

Nano-Micro Letters (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.