Abstract

Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) encoding virulence and resistance genes are widespread in bacterial pathogens, but it has remained unclear how they occasionally jump to new host species. Staphylococcus aureus clones exchange MGEs such as S. aureus pathogenicity islands (SaPIs) with high frequency via helper phages. Here we report that the S. aureus ST395 lineage is refractory to horizontal gene transfer (HGT) with typical S. aureus but exchanges SaPIs with other species and genera including Staphylococcus epidermidis and Listeria monocytogenes. ST395 produces an unusual wall teichoic acid (WTA) resembling that of its HGT partner species. Notably, distantly related bacterial species and genera undergo efficient HGT with typical S. aureus upon ectopic expression of S. aureus WTA. Combined with genomic analyses, these results indicate that a ‘glycocode’ of WTA structures and WTA-binding helper phages permits HGT even across long phylogenetic distances thereby shaping the evolution of Gram-positive pathogens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major parts of bacterial genomes consist of genetic material originating from other organisms. Many of these elements can be mobilized and exchanged by horizontal gene transfer (HGT) thereby shaping bacterial genome plasticity and permitting rapid adaptation to changing environmental challenges1. HGT of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) usually occurs at high frequency only among closely related bacterial clones because the transfer mechanisms, phage-mediated transduction or plasmid conjugation, rely on specific recognition of cognate recipient strains1,2. However, HGT also occurs between members of different species or even genera albeit with lower frequency. Such rare events are responsible for the import of new genes into the species’ genetic pool along with the emergence of new phenotypic properties; they are particularly important for evolution of new bacterial pathogen lineages with new virulence and antibiotic resistance traits.

The major human pathogen Staphylococcus aureus represents a paradigm for studying the roles of ‘short-distance’ HGT between strains of the same species and ‘long-distance’ HGT with other species or genera. MGEs and non-mobile genomic islands constitute ca. 22% of the S. aureus genomes and govern the virulence and colonization capacities, host-specificity and antibiotic resistance of the various clonal complexes3,4. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus carrying staphylococcal cassette chromosomes with mecA genes represent the most frequent cause of severe community- or healthcare-associated infections in many developing and developed countries5,6. While conjugation and uptake of naked DNA by natural transformation seem to occur rarely4,7, staphylococcal HGT of MGEs is generally believed to depend largely on transducing helper phages4. Certain temperate phages of serogroup B such as Φ11 or Φ80α have been shown to be capable of transducing DNA between S. aureus clones and to employ the N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc) residues on wall teichoic acid (WTA), a surface-exposed glycopolymer, as receptor4,8. WTA is produced by most Gram-positive bacteria and usually has species- or strain-specific structure9. S. aureus produces a WTA polymer composed of ca. 40 ribitol-phosphate (RboP) repeating units modified with α- and/or β-linked GlcNAc and D-alanine9,10 while the various coagulase-negative staphylococcal species (CoNS) produce WTA with glycerophosphate (GroP) or hexose-containing, complex repeating units modified with different types of sugars11.

S. aureus pathogenicity islands (SaPIs) are exchanged among S. aureus lineages with high frequency by SaPI particles consisting of SaPI genomes and structural proteins from helper phages12,13. While such ‘short-distance’ HGT events occur with high frequency, antibiotic resistance-mediating MGEs have been acquired only occasionally from other bacterial species. Of note, β-lactam antibiotic resistance genes from CoNS have frequently been imported into S. aureus14 whereas enterococcal vancomycin resistance genes have emerged in staphylococci only in a few exceptional cases15 suggesting that there are mechanisms involved that favour or disfavour specific ‘long-distance’ HGT events. Restriction modification systems16,17,18 and rarely occurring clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) sequences19 have been shown to interfere with HGT efficiency in staphylococci but the major determinants permitting HGT with other bacterial species and genera have remained unknown.

We demonstrate here that the variable structure of glycosylated WTA constitutes a ‘glycocode’ that is sensed by transducing phages thereby defining the routes of HGT. Similar WTA structures enable DNA exchange via helper bacteriophages even across the boundaries of species or genera, whereas S. aureus clones producing altered WTA become separated from the species’ genetic pool and may initiate new routes of HGT with other bacterial species and genera that share related WTA. Thus, related WTA structures are sufficient to initiate HGT even across long phylogenic distances.

Results

ST395 cannot undergo HGT with other S. aureus lineages

The various S. aureus clonal complexes differ largely in their epidemic potential and number of MGEs4. We compared several S. aureus lineages for capability to acquire SaPI1 or SaPIbov1 originating from sequence types ST8 and ST151, respectively13. Derivatives of these SaPIs with antibiotic resistance gene markers20 were transferred from S. aureus ST8 to a variety of potential recipient strains using helper phages Φ11 (for SaPIbov1) or Φ80α (for SaPI1). The majority of the sequence types acquired SaPIs albeit with varying efficiency, probably as a consequence of different restriction modification systems16,17,18 (Fig. 1a). In contrast, several independent clones of the ST395 lineage from various parts of the world including isolates from the lung or blood stream infections and nasal swabs (Supplementary Table S1)21,22,23 were completely resistant to HGT of SaPIs (Fig. 1a). Restriction modification systems were obviously not responsible for HGT resistance of ST395 because consecutive inactivation of the genes for type I (ΔhsdR) and type IV (ΔsauUSI) restriction systems in the ST395 strain PS187 did not enable transfer of SaPIs (Fig. 1a), whereas it considerably increased the rates of plasmid electroporation (Fig. 1b).

(a) Various S. aureus sequence types and ST395 mutants lacking restriction modifications systems SauUSI or SauUSI plus HsdR were analysed for capacities to acquire SaPIbov1 or SaPI1 via helper phages Φ11 or Φ80α, respectively. SaPI donor strains were JP1794 (SaPIbov1) and JP3602 (SaPI1). Values represent the ratio of transduction units (TRU; transductants per ml phage lysate) to plaque-forming units (PFU; plaques per ml phage lysate on S. aureus RN4220 w.t.) given as means (n=3)±s.d. No TRU were observed in controls lacking phages or SaPI particles. (b) S. aureus PS187 w.t. and mutants lacking restriction modification systems were analysed for capacities to acquire the tetracycline resistance plasmid pT181 via electroporation. Values represent the CFU per microgram DNA and given as means (n=3)±s.d. CFU, colony forming units. No CFU were observed in controls lacking donor DNA. ΔhsdR, no type I restriction modification system. ΔsauUSI, no type IV restriction modification system, lacks SAOUHSC_02790 homologue of NCTC8325. Statistically significant differences compared with wild type (w.t.) calculated by the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test are indicated: NS, not significant, P>0.05; *P<0.01 to<0.05; **P<0.001 to 0.01; ***P<0.001.

Φ187 mediates HGT between ST395 and other bacterial species

While strain PS187 was resistant to infection by Φ80α or Φ11 (Supplementary Fig. S1a), it has previously been shown to be susceptible to phage Φ187 (refs 21, 24). Interestingly, most ST395 but none of the other S. aureus sequence types could be infected by Φ187 (Supplementary Figs S1a and S2a). When Φ187 was analysed for its capacity to transfer MGEs, it was found to facilitate indeed the exchange of SaPI187β (found in the PS187 genome, see below) and SaPIbov1 between different ST395 isolates but not to other S. aureus sequence types (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, it also mediated HGT of SaPIbov1 and SaPI187β from ST395 to the CoNS species Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus carnosus and even to Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4e (Fig. 2). Thus, ST395 can participate in HGT with other species and genera while it is separated from phage-dependent HGT with typical S. aureus.

S. aureus ST395 strains with or without WTA or other Gram-positive bacteria were analysed for capacities to acquire SaPIbov1 or SaPI187β via helper phage Φ187. SaPI donor strains were VW1 (SaPIbov1) and VW7 (SaPI187β). Values represent the ratio of transduction units (TRU; transductants per ml phage lysate) to plaque-forming units (PFU; plaques per ml phage lysate on S. aureus PS187 w.t.) given as means (n=3)±s.d. No TRU were observed in controls lacking phages or SaPI particles. ΔtagO, no WTA. c-tagO, ΔtagO complemented with tagO. ND, not determined due to marker resistance or spontaneous occurring clones.

ST395 has a unique WTA gene cluster and WTA structure

PS187 was sequenced to obtain a prototype ST395 genome. The draft sequence was assembled into 16 large contigs plus two plasmids encompassing 2,529 open reading frames along with 43 and 10 coding sequences for transfer RNAs and ribosomal ribonucleic acid RNAs, respectively. PS187 was found to be a true S. aureus but to branch deeply in the S. aureus lineage (Fig. 3a). It did not encode CRISPR determinants indicating that the unusual HGT behaviour of ST395 is probably not mediated by ‘adaptive immunity’ to foreign DNA19. Among several unusual MGEs (see below) PS187 contained a novel genomic element, which encompassed transposon-related sequences plus four genes with similarity to WTA-biosynthetic genes (tagV, tagN, tagD, tagF) (Fig. 3b). Of note, the new element replaced the 11-kb tarIJLFS cluster for biosynthesis of GlcNAc-modified RboP (RboP-GlcNAc) WTA10, which is found in all other so far known S. aureus genomes. Different ST395 clones were found to be related because they exhibited similar DNA fragment patterns in pulsed field gel electrophoreses albeit with some variation in the size of certain DNA bands (Supplementary Fig. S2b). Moreover, all of the 10 available ST395 isolates were tested positive for the tagN gene encoded on the new genetic element indicating that the new WTA gene cluster is probably a common feature in the ST395 lineage (Supplementary Fig. S2c). WTA was isolated from PS187 and NMR-based structural elucidation demonstrated that PS187 produces a unique WTA type with an N-acetyl-D-galactosamine (GalNAc) modified GroP backbone (GroP-GalNAc) (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Fig. S3a and Supplementary Table S2), which was in agreement with an earlier analysis of PS187-related strains11.

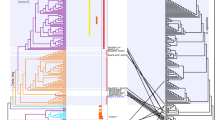

(a) Phylogenetic relationships of S. aureus sequence types based on DNA sequences from 1,147 orthologous genes. The genome of S. epidermidis RP62A was used for rooting the tree. Asterisks indicate 100% branch support in both, the maximum-likelihood tree and the Bayesian maximum clade credibility tree. (b) ST395 bears a novel WTA-biosynthetic gene cluster. Genetic organization of the RboP-GlcNAc WTA-biosynthetic tar cluster found in all S. aureus genomes (upper cluster) that is replaced by a new gene cluster containing putative WTA-biosynthetic genes (green) in ST395 strain PS187 (lower cluster). Gene locus numbers are indicated. Protein sequence alignments of the characteristic ST395 WTA proteins with homologues from CoNS can be found in Supplementary Fig. S6. (c) The chemical structure of the WTA repeating unit of S. aureus strain PS187 WTA (GroP-α-D-GalpNAc).

Some unusual MGEs from ST395 may be originating from CoNS

Because of its inability to exchange DNA with typical S. aureus, we assumed that ST395 may be genetically isolated. ST395 clones have been occasionally described as human commensals and invasive pathogens22,23 and a recent study has found that ST395 accounts for 5 and 2% of S. aureus nasal and blood culture isolates, respectively, in Northeastern Germany23. However, the actual numbers may be higher because ST395 isolates are usually methicillin susceptible and such clones are hardly collected and typed. Interestingly, early reports from the 1960s have pointed to a canine reservoir of PS187-related S. aureus25. In accord with this notion, we found the sequences of some of the host range-determining proteins of PS187 (IsdB and VwBP)26 to differ from typical human strains whereas the presence of the strictly human-specific chp, scn and sak genes26 suggests that PS187 is at least in part adapted to the human host.

Most MGEs of PS187 were distinct in synteny and composition from those found in other S. aureus genomes and some were even more related to MGEs found in CoNS. The genomic islands vSAα and vSAβ found in all previously sequenced S. aureus genomes were also present in PS187 but lacked typical enterotoxin or lantibiotic gene clusters, respectively (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. S4). Two novel PS187 SaPIs named SaPI187α and SaPI187β shared attachment (att) sites and some similarity with SaPI3 and SaPI122, respectively13, but differed with regard to enterotoxin, multidrug resistance transporter and serine protease genes (Fig. 4b,c and Supplementary Fig. S4). PS187 was found to encode two cryptic prophages named ΦPS187a and ΦPS187b (Supplementary Fig. S4), which were similar to previously described S. aureus phages Φ77 (ref. 8) and Φ187 (refs 21, 24) and were integrated in the genes for sphingomyelinase (hlb) and the giant surface protein Ebh, respectively. However, both prophages were defective as no infective phages could be obtained from PS187 upon treatment with the prophage-inducing agent mitomycin C (Supplementary Fig. S5). Φ77 was found to have entirely different host binding specificities from Φ187 with efficient adsorption to S. aureus with RboP-GlcNAc WTA and inefficient binding to bacteria with other WTA types such as ST395 (Supplementary Fig. S1b) suggesting that the defective Φ77-related prophage of PS187 may have originated from an ancient HGT event before the new WTA-biosynthetic genes had been acquired.

(a) Genetic organization of the two genomic islands found in PS187. The organization of PS187 vSAα is similar to that of other S. aureus genomes. The vSAβ of PS187 lacks typical enterotoxin or lantibiotic clusters found in all other vSAβ types sequenced so far. (b) Comparison of SaPI187α from PS187 and SaPI3 from typical S. aureus genomes. SaPI187α shares the att site with SaPI1, SaPI3 and SaPI5 and was found to be similarly organized as SaPI3 from S. aureus Col. Note the presence of a novel enterotoxin in SaPI187α designated as enterotoxin SeW. (c) Comparison of SaPI187β from PS187 and SaPI122 from S. aureus RF122. Although SaPI187β shares the att site with SaPI122 the SaPI122-characteristic gene encoding a multidrug resistance protein is absent in SaPI187β. Instead SaPI187β encodes a new serine protease. (d) Comparative map of mercury and cadmium resistance operons on a large plasmid from PS187 and corresponding genes from the S. epidermidis ATCC12228 SCC composite island (right) and the S. epidermidis RP62A integrated plasmid vSE1 (left). Dotted lines indicate sequence identities above >92% (DNA level) and 93% (protein level). Gene locus numbers are listed and ORFs are coloured according to functional categories as indicated.

Notably, some of the PS187 MGEs shared higher similarity with genes from CoNS than from other S. aureus. This was found for mercury and cadmium resistance operons on a large plasmid, which were most similar to corresponding genes from an S. epidermidis SCC island27 and the chromosomally integrated S. epidermidis plasmid vSe128 (Fig. 4d), respectively, and for the new WTA-biosynthetic genes, whose products exhibited highest similarity with proteins from Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (TagV), S. carnosus (TagN), Staphylococcus lugdunensis (TagD), and Staphylococcus simiae (TagF) (Supplementary Fig. S6). Thus, the genome sequence confirms that ST395 clones are separated from frequent HGT with typical S. aureus but have access to MGEs from CoNS.

SaPI particles adopt receptor requirements of helper phages

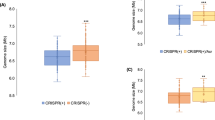

The unusual WTA structure of PS187 resembled that of the CoNS strains accepting SaPI DNA from ST395 via Φ187 (Table 1) suggesting that similar WTA structure may be a crucial determinant for the initiation of phage-dependent gene transfer even between distantly related bacteria. However, while S. aureus Φ80α or Φ11 phage particles are known to require a defined WTA structure for adsorption to host bacteria8, the receptor requirements of SaPI particles, which have a much broader host range than helper phages29, has remained unknown. Using defined mutants of the ST8 strains RN4220 (refs 8, 10) and Newman with altered teichoic acids, the susceptibilities to phage Φ80α or Φ11 particle binding and infection were compared with their capacities to acquire SaPI DNA from SaPI particles derived from the same helper phages. Infection by both, phage particles and SaPI particles, was dependent on the presence of WTA and WTA glycosylation (Fig. 5a; Supplementary Fig. S7) whereas lipoteichoic acid was dispensable (Fig. 5a) indicating that SaPI particles adopt the receptor requirements of the corresponding helper phage. In accord with this finding, inactivation of tagO encoding the first enzyme of the WTA-biosynthetic pathway rendered strain PS187 resistant to Φ187 infection because of impaired adsorption (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b) and to Φ187-dependent SaPI transfer (Fig. 2) indicating that Φ187 and Φ187-derived SaPI particles require GroP WTA for binding to host bacteria.

S. aureus RN4220 (ST8) strains with, with altered or without WTA (a) or S. aureus PS187 (ST395) or other Gram-positive bacterial species expressing genes for biosynthesis of RboP-GlcNAc WTA (b) were analysed for capacities to acquire SaPIbov1 or SaPI1 via helper phages Φ11 or Φ80α, respectively. SaPI donor strains were JP1794 (SaPIbov1) and JP3602 (SaPI1). Values represent the ratio of transduction units (TRU; transductants per ml phage lysate) to plaque-forming units (PFU; plaques per ml phage lysate on S. aureus RN4220 w.t.) given as means (n=3)±s.d. No TRU were observed in strains expressing WTA other than RboP-GlcNAc. ΔtagO, no WTA; ΔltaS (4S5), no lipoteichoic acid; c-tagO, ΔtagO complemented with tagO; ΔtarM ΔtarS, no WTA glycosylation; c-tarM and c-tarS, ΔtarM ΔtarS complemented either with tarM or tarS. WTA hybrid strains expressing additional RboP-GlcNAc WTA are indicated with H.

WTA structure governs the capacity to undergo HGT

In order to elucidate if it is indeed the similarity of WTA structures that determines if two bacterial strains can exchange DNA via helper phages, even if they are not closely related, we cloned the minimal set of genes (tarFIJLS) from S. aureus RN4220 (ST8) required for biosynthesis of RboP-GlcNAc WTA10 and introduced the resulting plasmid into bacteria that were not susceptible to HGT with typical RboP-WTA expressing S. aureus. The plasmid-transformed strain PS187-H was indeed found to produce two types of WTA as NMR analysis revealed the presence of both, RboP-GlcNAc WTA and GroP-GalNAc WTA (Supplementary Fig. S3b and Supplementary Table S3) indicating that two different WTA-biosynthetic machineries can be simultaneously functional in bacterial cells. Growth or morphology of these hybrid strains did not show obvious alterations (Supplementary Fig. S8a,b). Indeed, upon expression of RboP-GlcNAc WTA ST395 strains PS187 and NRS111 became susceptible to Φ80α or Φ11-dependent HGT of SaPI1 and SaPIbov1, respectively (Fig. 5b) or of the tetracycline resistance plasmid pT181 (Supplementary Fig. S9) from typical S. aureus. Moreover, distantly related bacteria such as S. epidermidis, S. carnosus, S. capitis, and even L. monocytogenes serotype 4e, which are usually resistant to Φ80α or Φ11-dependent HGT, acquired the capacity to take up SaPIs from typical S. aureus upon expression of tarFIJLS at similarly high rates as RboP-GlcNAc WTA-producing S. aureus (Fig. 5b). Of note, successful SaPI transfer correlated with increased phage adsorption upon RboP-GlcNAc WTA expression (Supplementary Fig. S1c). These results demonstrate that related WTA structures can be sufficient for allowing MGE exchange via helper phages even across long phylogenetic distances.

In accord with this finding, a systematic analysis with several Gram-positive bacteria revealed a strong correlation between WTA structure and the capacity to exchange resistance and virulence genes with either typical S. aureus via Φ11 or Φ80α (for example, Listeria grayi) or with ST395 via Φ187 (for example, S. epidermidis and other CoNS) (Table 1). The susceptibility of L. monocytogenes serotype 4e to Φ187-mediated HGT was reflected by efficient binding of Φ187 (Supplementary Fig. S1b). It may be due to the decoration of WTA with galactose, which may facilitate binding of Φ187-derived SaPI particles in a similar way as GalNAc. Of note, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium or Enterococcus faecalis could not undergo HGT with any S. aureus probably because of the very complex enterococcal WTA structures30,31.

Discussion

HGT between S. aureus and other bacterial species and genera contributes substantially to the evolution of new epidemic clones, but it has remained unclear if it occurs accidentally or follows certain rules. While restriction modification and CRISPR systems have been shown to limit HGT efficiency16,17,18,19, no data on the criteria that need to be fulfilled by the HGT partners to initiate phage-dependent MGE exchange have been available. Our studies with naturally occurring and engineered bacterial strains with atypical WTA demonstrate that related WTA structures of MGE donor and recipient are sufficient to permit HGT even across long phylogenetic distances. While helper phage particles are known to have quite narrow host ranges for parasitic reproduction29, we found that their receptor specificities govern the capacity to transmit MGEs to a broad range of recipient strains expressing cognate surface ligands. On the other hand, changes in helper phage receptor structures can enable binding of new types of helper phages and redirect the routes of HGT, which may facilitate the development of new clonal lineages and species.

The structurally diverse WTA molecules represent a species or lineage-specific signature at the surface of Gram-positive bacteria. WTA has several important roles for bacterial physiology such as the control of autolytic and peptidoglycan-biosynthetic enzymes9, but all these functions could be achieved without extensive variation of its structure. Our data indicate that WTA structure constitutes a species- or lineage-defining ‘glycocode’ governing the bacterial access to a common genetic pool via WTA-specific helper phages. A thorough investigation of WTA structures and cognate phage receptor specificities will enable to assess how likely the transfer of new antibiotic resistance genes across the boundaries of species and genera will be in the future. Antibiotic stress is known to activate prophages thereby probably contributing to phage-mediated HGT32. In contrast, recently developed compounds blocking the biosynthesis of WTA33 may help to reduce the frequency of phage-dependent HGT for example, in chronic polymicrobial infections.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth media

The various bacterial strains listed in Supplementary Table S1 were grown in BM broth (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl, 0.1% K2HPO4, 0.1% glucose) or Luria Bertani Broth supplemented with appropriate antibiotics at a concentration of 10 μg ml−1 (chloramphenicol), 3 μg ml−1 (tetracycline) or 100 μg ml−1 (ampicillin). In order to assess the growth and microscopic properties of mutant strains, phenotypic characterization of WTA hybrid strains overnight cultures were diluted to OD578 0.1 in BM and grown at 37 °C on a shaker. Samples for microscopy were analysed after 3-h growth using a Leica DMRE microscope and Leica HCX 100 × objective. Bacterial growth was monitored for 8 h.

Molecular genetic methods

For the construction of marker-less ΔtagO, ΔsauUSI and ΔsauUSI ΔhsdR mutants in S. aureus PS187, the pKOR1 shuttle vector was used according to standard procedures34. For knockout plasmid construction, primers listed in Supplementary Table S4 were used. To label SaPI187β with an antibiotic resistance marker, the ermB gene was integrated into SaPI187β using the pKOR1 system. Knock-in primers are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

For amplification of the genomic region coding for tarF, tarI2, tarJ2, tarL2 and tarS from genomic DNA (RN4220 w.t.) primers, Tar-up and Tar-dn were used. The PCR product was cloned in the E. coli/S. aureus shuttle vector pRB47435 at the BamHI/EcoRI restriction sites resulting in plasmid pRB474-tarFI2J2L2S. The plasmid was isolated from E. coli TOP10 or E. coli DC10B and used to transform target strains resulting in hybrid WTA-producing strains S. aureus PS187-H and NRS111-H, S. carnosus TM300-H, S. capitis ATCC27840-H and S. epidermidis 1457-H. L. monocytogenes ATCC19118 was transformed by electroporation36 resulting in strain L. monocytogenes ATCC19118-H.

For plasmid transformation, 50 μl competent cells were mixed with 500 ng pT181 plasmid DNA, incubated at room temperature for 30 min, transferred into a 1-mm gap electroporation cuvette and pulsed at 1,000 volts. Immediately after electroporation, 950 μl BM medium was added followed by 70-min incubation at 37 °C. Cells were finally plated onto selective media and transformants were counted to calculate electroporation efficiency.

Pulsed field gel electrophoresis typing was performed according to Goerke et al.37 tagN genotyping of available ST395 isolates was performed using primers N-up and N-dn (Supplementary Table S4).

Experiments with phages and SaPI particles

For rapid determination of phage susceptibility, the soft agar spot assay was performed according to Xia et al.38 A phage panel encompassing broad host range phage ΦK (ref. 38), serogroup L phage Φ187 (ref. 39), two serogroup B phages Φ11 (ref. 39) and Φ80α40 and serogroup F phage Φ77 (ref. 8) (Supplementary Table S5) was used. The various phages were propagated on S. aureus RN4220 (ΦK, Φ11, Φ80α, Φ77) or PS187 (Φ187). Mitomycin C induction experiments confirmed that these two propagation strains released no phage particles from endogenous prophages thereby ensuring that no other than the propagated phages were present in the obtained lysates. In order to determine phage adsorption rates, the multiplicity of infection was set to 0.005 (for Φ187) or 0.1 (for Φ80α and Φ77). Adsorption was calculated by determining the PFU of the unbound phage in the supernatant and subtracting it from the total number of input PFU. Adsorption efficiency was indicated relative to the adsorption on the parental wild-type strain (RN4220 or PS187), which was set to 100%. Prophages or SaPI particles were induced with 1 μg ml−1 mitomycin C.

For phage-mediated SaPI and plasmid transfer, recipient strains were grown overnight and used for HGT experiments. Approximately 8.0 × 107 bacteria were mixed with 100 μl of SaPI lysates produced from S. aureus strains JP1794 or JP3602 bearing the resistance marker-labelled SaPIbov1 (~1.0 × 106 PFU ml−1) or SaPI1 (~3.0 × 107 PFU ml−1), respectively (Supplementary Table S1), incubated for 15 min at 37 °C, diluted, and plated on BM agar supplemented with appropriate antibiotics.

For Φ187-mediated SaPIbov1 transfer, the PS187-H strain producing RboP and GroP WTA was transduced by Φ11 with SaPIbov1. The resulting strain VW1 was infected with Φ187 and 100 μl of the resulting lysate (~1.3 × 1010 PFU ml−1) was used to infect recipient strains as mentioned above. Note that for Φ187-mediated SaPIbov1 transduction of Listeria strains, the used lysate contained only ~5.0 × 105 PFU ml−1. For Φ187-mediated SaPI187β transfer, SaPI187β was labelled with the ermB resistance marker in S. aureus PS187 wild type resulting in strain VW7, which was subsequently infected with Φ187 and 100 μl of the obtained lysate (~3.0 × 107 PFU ml−1) was used to infect recipient strains as mentioned above. To exclude that transductants resulted from spontaneous uptake of nicked DNA, SaPI-containing lysates were treated with 20 U DNase I for 1 h at 37 °C and used for SaPI transfer experiments. For plasmid transduction, pT181-bearing RN4220 was infected with Φ80α and the lysate was used to infect recipient strains. Approximately 8.0 × 107 bacteria were resuspended in phage buffer (100 mM MgSO4, 100 mM CaCl2, 1 M Tris–HCl, pH 7.8, 0.59% NaCl, 0.1% gelatine) and mixed with 100 μl lysate (~1.1 × 108 PFU ml−1), incubated for 10 min at 37 °C, mixed with soft agar and poured onto BM agar plates containing 12.5 μg ml−1 tetracycline. Transductants were counted after overnight incubation (SaPIs) or after 48 h at 37 °C (pT181 and Listeria assays) and transduction efficiency was calculated. SaPI transfer was confirmed by molecular typing of resistance marker.

WTA extraction and purification

WTA was isolated as described previously with minor modifications41. Briefly, overnight cultures were washed and disrupted in a cell disrupter (Euler). Cell lysates were incubated at 37 °C overnight in the presence of DNase and RNase. SDS was added to a final concentration of 2% followed by ultrasonication for 15 min. Cell walls were washed several times to remove SDS. To release WTA from cell walls samples were treated with 5% trichloroacetic acid for 4 h at 65 °C. Peptidoglycan debris was separated via centrifugation (10 min, 14,000g). Determination of inorganic phosphate as described previously41 was used for WTA quantification. These crude WTA extracts were further purified as described previously with minor modifications38. Briefly, the pH of the crude extract was adjusted to 5.5 with NaOH and dialyzed against water with a Spectra/Por3 dialysis membrane (MWCO of 3.5 kDa; VWR International GmbH, Darmstadt). Samples were concentrated in a SpeedVac concentrator at 45 °C to 5 ml and applied to DEAE-Sephadex A25 matrix according to Xia et al.38 For elution from DEAE-Sephadex A25 matrix 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.2 0.35 M NaCl was used. The eluate was dialyzed again against water and concentrated to 1 ml. The purified WTA samples were stored at 20 °C for further analysis. All general analytical chemistry and NMR spectroscopy methods for WTA characterization are described in detail in the supplementary section.

Genome sequencing and analyses

S . aureus PS187 was sequenced initially by Roche 454 pyrosequencing (Roche GS-FLX system), then resequenced by using Illumina technology (Illumina HiSeq2000) at a 150-fold coverage. Details are described in supplementary section.

Additional information

Accession codes: The Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession number ARPA00000000 (BioProject PRJNA197438). The version described in this paper is the first version, ARPA01000000.

How to cite this article: Winstel, V. et al. Wall teichoic acid structure governs horizontal gene transfer between major bacterial pathogens. Nat. Commun. 4:2345 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3345 (2013).

Accession codes

References

Thomas, C. M. & Nielsen, K. M. Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 711–721 (2005).

Frost, L. S., Leplae, R., Summers, A. O. & Toussaint, A. Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 722–732 (2005).

Malachowa, N. & DeLeo, F. R. Mobile genetic elements of Staphylococcus aureus. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67, 3057–3071 (2010).

Lindsay, J. A. Genomic variation and evolution of Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300, 98–103 (2010).

Chambers, H. F. & Deleo, F. R. Waves of resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 629–641 (2009).

Mediavilla, J. R., Chen, L., Mathema, B. & Kreiswirth, B. N. Global epidemiology of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA). Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15, 588–595 (2012).

Morikawa, K. et al. Expression of a cryptic secondary sigma factor gene unveils natural competence for DNA transformation in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1003003 (2012).

Xia, G. et al. Wall teichoic acid-dependent adsorption of staphylococcal siphovirus and myovirus. J. Bacteriol. 193, 4006–4009 (2011).

Weidenmaier, C. & Peschel, A. Teichoic acids and related cell-wall glycopolymers in Gram-positive physiology and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 276–287 (2008).

Brown, S. et al. Methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus requires glycosylated wall teichoic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 18909–18914 (2012).

Endl, J., Seidl, P. H., Fiedler, F. & Schleifer, K. H. Determination of cell wall teichoic acid structure of staphylococci by rapid chemical and serological screening methods. Arch. Microbiol. 137, 272–280 (1984).

Tallent, S. M., Langston, T. B., Moran, R. G. & Christie, G. E. Transducing particles of Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island SaPI1 are comprised of helper phage-encoded proteins. J. Bacteriol. 189, 7520–7524 (2007).

Novick, R. P., Christie, G. E. & Penades, J. R. The phage-related chromosomal islands of Gram-positive bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 541–551 (2010).

Otto, M. Coagulase-negative staphylococci as reservoirs of genes facilitating MRSA infection: staphylococcal commensal species such as Staphylococcus epidermidis are being recognized as important sources of genes promoting MRSA colonization and virulence. Bioessays 35, 4–11 (2012).

Perichon, B. & Courvalin, P. VanA-type vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 53, 4580–4587 (2009).

Corvaglia, A. R. et al. A type III-like restriction endonuclease functions as a major barrier to horizontal gene transfer in clinical Staphylococcus aureus strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 11954–11958 (2010).

Waldron, D. E. & Lindsay, J. A. Sau1: a novel lineage-specific type I restriction-modification system that blocks horizontal gene transfer into Staphylococcus aureus and between S. aureus isolates of different lineages. J. Bacteriol. 188, 5578–5585 (2006).

Monk, I. R., Shah, I. M., Xu, M., Tan, M. W. & Foster, T. J. Transforming the untransformable: application of direct transformation to manipulate genetically Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. mBio 3, piie00277-11 (2012).

Marraffini, L. A. & Sontheimer, E. J. CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in staphylococci by targeting DNA. Science 322, 1843–1845 (2008).

Tormo, M. A. et al. Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island DNA is packaged in particles composed of phage proteins. J. Bacteriol. 190, 2434–2440 (2008).

Asheshov, E. A. & Jevons, M. P. The effect of heat on the ability of a host strain to support the growth of a Staphylococcus phage. J. Gen. Microbiol. 31, 97–107 (1963).

Francois, P. et al. Evaluation of three molecular assays for rapid identification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 2011–2013 (2007).

Holtfreter, S. et al. Clonal distribution of superantigen genes in clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 2669–2680 (2007).

Rosenblum, E. D. & Tyrone, S. Serology, Density, and Morphology of Staphylococcal Phages. J. Bacteriol. 88, 1737–1742 (1964).

Meyer, W. A proposal for subdividing the species Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 17, 387–389 (1967).

McCarthy, A. J. et al. The distribution of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) in MRSA CC398 is associated with both host and country. Genome Biol. Evol. 3, 1164–1174 (2011).

Mongkolrattanothai, K., Boyle, S., Murphy, T. V. & Daum, R. S. Novel non-mecA-containing staphylococcal chromosomal cassette composite island containing pbp4 and tagF genes in a commensal staphylococcal species: a possible reservoir for antibiotic resistance islands in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 48, 1823–1836 (2004).

Gill, S. R. et al. Insights on evolution of virulence and resistance from the complete genome analysis of an early methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain and a biofilm-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis strain. J. Bacteriol. 187, 2426–2438 (2005).

Chen, J. & Novick, R. P. Phage-mediated intergeneric transfer of toxin genes. Science 323, 139–141 (2009).

Bychowska, A. et al. Chemical structure of wall teichoic acid isolated from Enterococcus faecium strain U0317. Carbohydr. Res. 346, 2816–2819 (2011).

Geiss-Liebisch, S. et al. Secondary cell wall polymers of Enterococcus faecalis are critical for resistance to complement activation via mannose-binding lectin. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 37769–37777 (2012).

Ubeda, C. et al. Antibiotic-induced SOS response promotes horizontal dissemination of pathogenicity island-encoded virulence factors in staphylococci. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 836–844 (2005).

Suzuki, T., Swoboda, J. G., Campbell, J., Walker, S. & Gilmore, M. S. In vitro antimicrobial activity of wall teichoic acid biosynthesis inhibitors against Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 55, 767–774 (2011).

Bae, T. & Schneewind, O. Allelic replacement in Staphylococcus aureus with inducible counter-selection. Plasmid 55, 58–63 (2006).

Bruckner, R. A series of shuttle vectors for Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli. Gene 122, 187–192 (1992).

Promadej, N., Fiedler, F., Cossart, P., Dramsi, S. & Kathariou, S. Cell wall teichoic acid glycosylation in Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b requires gtcA, a novel, serogroup-specific gene. J. Bacteriol. 181, 418–425 (1999).

Goerke, C. et al. Diversity of prophages in dominant Staphylococcus aureus clonal lineages. J. Bacteriol. 191, 3462–3468 (2009).

Xia, G. et al. Glycosylation of wall teichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus by TarM. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 13405–13415 (2010).

Pantucek, R. et al. Identification of bacteriophage types and their carriage in Staphylococcus aureus. Arch. Virol. 149, 1689–1703 (2004).

Christie, G. E. et al. The complete genomes of Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophages 80 and 80alpha--implications for the specificity of SaPI mobilization. Virology 407, 381–390 (2010).

Weidenmaier, C. et al. Role of teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization, a major risk factor in nosocomial infections. Nat. Med. 10, 243–245 (2004).

Schleifer, K. H. &. Fischer, U. Description of a new species of the genus Staphylococcus: Staphylococcus carnosus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 32, 153–156 (1982).

Fiedler, F. Biochemistry of the cell surface of Listeria strains: a locating general view. Infection 16, (Suppl 2): S92–S97 (1988).

Acknowledgements

We thank Jacques Schrenzel, Gabriele Bierbaum, Christiane Wolz, Angelika Gründling, Matthias Marschal and Ian Monk for providing bacterial strains and phages and Peter Bauer and Claudia Bauer for help with genome sequencing. This work was supported by grants TRR34 to A.P., B.M.B., and T.D. and SFB766 to G.X. and A.P. from the German Research Council, grants from the German Center for Infectious Disease Research to A.P. and G.X., and SkinStaph and Menage grants to A.P. from the German Ministry of Education and Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.W., C.L., P. S.C., G.X., M.S. and M.M. performed the experiments and analysed the data; B.M.B. and J.R.P. provided essential materials; V.W., J.R.P., U.N., O.H., T.D., A.P. and G.X. conceived the study; V.W., A.P. and G.X. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S9, Supplementary Tables S1-S9 and Supplementary Methods (PDF 4386 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Winstel, V., Liang, C., Sanchez-Carballo, P. et al. Wall teichoic acid structure governs horizontal gene transfer between major bacterial pathogens. Nat Commun 4, 2345 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3345

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3345

This article is cited by

-

Deciphering the role of monosaccharides during phage infection of Staphylococcus aureus

Nano Research (2022)

-

Staphylococcus epidermidis clones express Staphylococcus aureus-type wall teichoic acid to shift from a commensal to pathogen lifestyle

Nature Microbiology (2021)

-

Multi-species host range of staphylococcal phages isolated from wastewater

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Analysis host-recognition mechanism of staphylococcal kayvirus ɸSA039 reveals a novel strategy that protects Staphylococcus aureus against infection by Staphylococcus pseudintermedius Siphoviridae phages

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2019)

-

Peculiarities of Staphylococcus aureus phages and their possible application in phage therapy

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.