Abstract

Organic light-emitting diodes are emerging as leading technologies for both high quality display and lighting. However, the transparent conductive electrode used in the current organic light-emitting diode technologies increases the overall cost and has limited bendability for future flexible applications. Here we use single-layer graphene as an alternative flexible transparent conductor, yielding white organic light-emitting diodes with brightness and efficiency sufficient for general lighting. The performance improvement is attributed to the device structure, which allows direct hole injection from the single-layer graphene anode into the light-emitting layers, reducing carrier trapping induced efficiency roll-off. By employing a light out-coupling structure, phosphorescent green organic light-emitting diodes exhibit external quantum efficiency >60%, while phosphorescent white organic light-emitting diodes exhibit external quantum efficiency >45% at 10,000 cd m−2 with colour rendering index of 85. The power efficiency of white organic light-emitting diodes reaches 80 lm W−1 at 3,000 cd m−2, comparable to the most efficient lighting technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The performance of organic light-emitting diodes has improved remarkably1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 in the last three decades. They are increasingly used in high-performance commercial displays owing to their many advantageous characteristics, which include vibrant colours, high contrast ratio, fast response time, thin and lightweight form factor, high energy efficiency and mechanical flexibility5,6,7. In addition to display applications, Organic light-emitting diode (OLED) lighting is emerging as a competitive low-cost solid state lighting solution due to its high performance and attractive properties, such as thin and large area form factor, broad colour spectrum, gentle and diffused light output, colour tunability, transparency and flexibility8,9,10.

Among all components in OLED devices, the transparent conducting electrode (TCE) is an essential part that directly determines device performance. To date, tin-doped indium oxide (ITO) is the material of choice for TCE in OLEDs1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 owing to its exceptional optical and electrical properties. However, it has considerable shortcomings that potentially limit the further development of OLED technology. ITO is brittle11,12 and unsuitable for future flexible, rollable, or foldable applications. ITO-TCE is rather expensive13,14 due to both the material cost and its low throughput deposition process. In addition, the indium in ITO is known to diffuse into the active layers of OLEDs, leading to performance degradation over time15. Therefore, there is a strong need for flexible, low-cost and chemically stable transparent electrodes for the next-generation OLED-based display and lighting.

The unique electrical and mechanical properties of graphene make it an excellent choice for a flexible transparent conductor16,17,18,19. Graphene can be chemically doped to a carrier density of ~1013 cm−2 while maintaining high carrier mobility20,21, leading to a surface resistance comparable to that of ITO. In addition, excellent mechanical properties of graphene allow no degradation of electrical properties upon bending17. The bending radius of graphene can be as small as a millimetre22, which is the smallest among all flexible transparent conductors. These attractive features have been explored by the experimental studies of using graphene electrodes in a wide range of devices including field-effect transistors23, touch screens24, liquid crystal displays25, solar cells26 and OLEDs27,28,29.

The early works of introducing graphene as TCE in OLEDs27,28 demonstrated some functional devices using multi-layer graphene (MLG) electrodes. The best efficiency is only ~1 cd A−1, lower than the control device made on ITO, mainly due to inefficient charge injection from the graphene electrode into the organic layers. Han et al.29 demonstrated much improved OLED peak efficiency on MLG electrodes, however, their devices exhibit severe efficiency roll-off at high current injection, and the white OLEDs (WOLEDs) show limited brightness and efficiency. Moreover, using MLG-TCE requires multiple graphene transfers (higher cost) and suffers the penalty of significant light absorption (each additional layer of graphene absorbs ~3% of light across the spectrum).

We demonstrate green OLEDs with current efficiency (CE) >240 cd A−1 at luminance of 20,000 cd m−2 (with light extraction), and CE >80 cd A−1 at 3,000 cd m−2 (without light extraction). WOLEDs with light extraction and without light extraction show CE >120 cd A−1 at 10,000 cd m−2 and >45 cd A−1 at 3,000 cd m−2, respectively. By using single-layer graphene (SLG) as a transparent electrode, the present work achieves record high brightness and efficiency for OLEDs on graphene TCEs (Supplementary Table S1). The demonstrated WOLED performance is already suitable for general lighting. The performance improvement is attributed to the highly efficient hole injection from SLG to light-emitting layers, eliminating the efficiency roll-off due to carrier trapping, charge imbalance, and exciton quenching at the anode/organic interface.

Results

Graphene properties

The SLG used in this work was grown via a chemical vapour deposition process on Cu foil30 and was transferred onto plastic or glass substrates31. The typical carrier density and mobility were measured to be 3 × 1012 cm−2 and 2,200 cm2 V−1 s−1, respectively, by Van der Pauw measurement at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. S1). The p-type chemical doping was then performed by soaking the graphene sample in 1 mg ml−1 triethyloxonium hexachloroantimonate (OA)/dichloroethene solution, producing the charge transfer complex shown in Fig. 1a. A similar doping process has been studied for carbon nanotubes32 and found to be stable over time, in contrast with the commonly used nitric acid doping. The work functions of graphene samples before and after chemical doping were measured by Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 1b). The peak position of G band of OA-doped graphene is at 1,608 cm−1 and that of undoped graphene is at 1,591 cm−1, while the ideal intrinsic graphene G peak is at 1,582 cm−1 (ref. 33). Assuming ΔΩG=ΔEF × 42 cm−1 eV−1 (refs 34, 35, 36), where ΔΩG is the G peak shift and ΔEF is the Fermi level shift, the work functions of OA-doped graphene and undoped graphene were measured to be 5.1 and 4.7 eV, respectively. After OA doping, the carrier density of SLG is increased to 2 × 1013 cm−2 and the sheet resistance is reduced from ~1 kΩ/□ to <200 Ω/□.

Direct hole injection

Conventional OLED structure uses hole transporting layers to match the energy level difference between the anode and the organic host material of light-emitting layers. The charge trapping induced charge imbalance and exciton quenching in these hole transporting layers are known to degrade the device performance37. In order to make high-efficiency high-brightness OLEDs, direct hole injection from anode to light-emitting layers is highly preferred. To achieve this, high work function anode is needed to match the deep highest-occupied-molecular-orbital (HOMO) energy level of host materials to light-emitting layers. Although OA-doped graphene has an enhanced work function of ~5.1 eV, it is not sufficient for direct hole injection into host materials such as 4,4′-bis(carbazol-9-yl)biphenyl (CBP), which has a HOMO level of 6.1 eV. Here we use anode interface layers consisting of the transition metal oxide to further enhance the work function of the graphene anode, similar to their roles of modifying the work function of ITO electrodes in organic electronics38,39,40,41,42,43. Note that metal oxides do not grow as uniform films on graphene due to the lack of nucleation to initialize the film growth44,45. The problem can be solved by firstly spin-coating a thin layer of conductive polymer, poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS), on graphene to ensure uniform wetting. A transition metal oxide interface layer, MoO3, was subsequently deposited by thermal evaporation on top of the PEDOT:PSS layer.

The AFM images of the MoO3 film on ITO and SLG are compared in Fig. 2 to verify the uniform deposition of MoO3. The as-deposited ITO has a surface RMS roughness of 0.69 nm. After depositing 3 nm MoO3, the surface exhibits a reduced roughness of 0.18 nm. On the other hand, after the deposition of 3 nm MoO3 directly on graphene transferred on glass, the surface roughness is significantly increased from 0.35 (Fig. 2a) to 0.97 nm due to MoO3 clusters, as can be seen from Fig. 2b. Although the surface can be eventually covered by growing very thick MoO3 layers, electrical characteristics will be degraded from the high resistance of thick MoO3 and non-uniform contact to graphene. With the same 3 nm MoO3 deposited on the PEDOT:PSS on graphene sample, the surface roughness is reduced from 0.82 (Fig. 2a) to 0.32 nm (Fig. 2d), similar to that of MoO3 on ITO, indicating uniform film growth. The measured transmittance of the MoO3/PEDOT/SLG stack is shown in Fig. 2e in comparison with SLG and double-layer graphene (DLG). The transmittance (T) of SLG is ~97% across the visible spectral range. Each additional layer of graphene degrades the transmittance by ~3%. The MoO3/PEDOT/SLG stack has transmittance above 95% across the visible range, which is higher than DLG and also much higher than PEDOT alone with similar sheet resistance46.

Atomic force microscopy (a–d) images of (a) SLG on polished silicon wafer, (b) 3 nm MoO3 on SLG on silicon, (c) 20 nm poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) on SLG on silicon and (d) 3 nm MoO3 on 20 nm PEDOT:PSS on SLG on silicon. The image size of each panel is 0.5 × 0.5 μm2; scale-bar, 100 nm long. (e) Transmission spectrum of the MoO3/PEDOT/SLG, SLG and DLG.

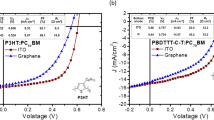

The direct hole injection from SLG into the light-emitting host material CBP were characterized by the electrical measurement of hole only devices. CBP (700 nm-thick) was sandwiched between the SLG anode and an Au cathode with various anode interface layers inserted between SLG and CBP. If the PEDOT:PSS interface layer is not used, an electrical short between SLG anode and Au cathode occurs due to non-uniform film growth. Figure 3a shows the current–voltage characteristics of hole only devices with a 20 nm PEDOT:PSS interface layer and a 20-nm PEDOT:PSS\3 nm MoO3 interface layer. The device with a PEDOT:PSS only interface layer (HOMO level=5.2 eV) shows a significant voltage drop at the contact due to the high energy barrier. When both PEDOT:PSS and MoO3 layers are used, the device exhibits a significantly lower turn-on voltage, suggesting that, with its high work function (~6.7 eV)41, MoO3 on top of PEDOT:PSS serves as an excellent anode interface layer on SLG for efficient hole injection into CBP. The concept is illustrated by the energy level diagram shown in Fig. 3b.

(a) Current–voltage characteristics of hole only devices consisting SLG anode/20 nm PEDOT:PSS/700 nm/100 nm Au cathode, SLG anode/20 nm PEDOT:PSS/3 nm MoO3/700 nm CBP/100 nm Au cathode and ITO anode/20 nm PEDOT:PSS/3 nm MoO3/700 nm CBP/100 nm Au cathode, and (b) the energy level diagram of the SLG anode/PEDOT:PSS/MoO3/CBP structure.

OLED on SLG structures

Phosphorescent green OLEDs and WOLEDs were fabricated on SLG TCEs on both plastic and glass substrates, as shown in Fig. 4. A thin CBP layer doped with MoO3 as p-doped hole injection layer was inserted to further enhance the hole injection efficiency into CBP. The green OLED (Fig. 4a) used a CBP layer doped with bis(2-phenylpyridine)(acetylacetonate)iridium(III) [Ir(ppy)2(acac)]47 as an emissive layer. The WOLED (Fig. 4b) used a CBP layer doped with Ir(ppy)2(acac) and bis(2-methyldibenzo[f,h]quinoxaline) (acetylacetonate) iridium (III) [Ir(MDQ)2(acac)] as the red emissive layer, a CBP layer doped with Ir(ppy)2(acac) as the green emissive layer, and a CBP layer doped with Bis(4,6-difluorophenylpyridinato-N,C2)picolinatoiridium (Firpic) as the blue emissive layer. A 2,2′,2′′-(1,3,5-benzinetriyl)-tris(1-phenyl-1-H-benzimidazole) (TPBi) electron transporting layer and a Al/LiF cathode completed both structures. All emissive materials were incorporated in a single host material to reduce charge trapping48. The same structures using ITO anodes on a glass substrate were also fabricated for comparison.

Phosphorescent green OLED performance

Figure 5a shows optical images of phosphorescent green OLEDs on SLG made on a flexible polyethylene terephthalate substrate. The current–voltage and the luminance-voltage characteristics in Fig. 5b show that OLEDs on SLG and on ITO have nearly identical behaviours, turning on at 2.6 V and reaching the luminance intensity of 1,000 cd m−2 at 4.2 V. These nearly identical characteristics from both devices are expected because of the use of MoO3 contact interface layers in both devices. The low turn-on voltage and a sharp rise of both the current density and luminance indicate low contact resistance as well as low electrode series resistance.

(a) Pictures of flexible OLEDs on plastic substrate on SLG electrode. (b) The current density and luminance as a function of driving voltage. (c) EQE as a function of luminance for OLEDs on SLG electrode on flexible PET substrate, OLEDs on ITO on glass substrate and OLEDs using NPB hole transporting layer on SLG, (d) PE and CE of green OLEDs on SLG and ITO with enhanced coupling structure. The error bars represent the s.d. of multiple measurement results.

The external quantum efficiency (EQE) of OLEDs fabricated on SLG is >20% with luminance as high as 3,000 cd m−2 (Fig. 5c). The corresponding CE is measured to be 80 cd A−1. As no light extraction scheme is used, the EQE is limited by the light out-coupling efficiency. Such high measured EQE suggests that near unity internal quantum efficiency is achieved for OLEDs with SLG. A relatively constant EQE up to 3,000 cd m−2 also indicates excellent charge injection from the SLG electrode to the organic materials, as charge trapping at the interface is known to cause a charge imbalance and exciton quenching, which induces efficiency roll-off at high luminance37,49,50. As can be seen in Fig. 5c, it is evident that the EQE of SLG-OLEDs on plastic is no less than that of the ITO-OLEDs on glass substrate. The EQE of OLEDs using the conventional hole transporting layer, N,N′-bis(Inaphthyl)-N,N′-diphenyl-1,1′-biphenyl-4,4′-diamine (NPB), is also plotted in Fig. 5c. The NPB device has the same structure as the one in Fig. 4a except that the CBP/CBP:MoO3/MoO3 layer stack is replaced with hole transporting layer NPB of the same thickness. It is clear that the EQE of NPB OLEDs on SLG has severer efficiency roll-off at high luminance owing to charge trapping induced charge imbalance and exciton quenching in the NPB. The flexibility of SLG-OLEDs was also tested by bending the substrate to a radius of 0.5 cm. The device exhibits the same performance before and after bending (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Light out-coupling structures (Supplementary Fig. S3) using high index substrate and high index lens9,10 were incorporated with OLEDs on SLG to further enhance the luminance and efficiency. Figure 5d shows that the power efficiency (PE) and CE of green OLEDs increase to >160 lm W−1 at 3,000 cd m−2, and >250 cd A−1 at a high brightness of 10,000 cd m−2, respectively. The EQE is >60% for a wide range of brightness up to 10,000 cd m−2. No CE roll-off can be observed below a brightness of 50,000 cd m−2, which is the highest brightness achieved by OLEDs on carbon-based electrodes.

SLG-OLEDs have a very different optical cavity than ITO-OLEDs, as SLG-OLEDs do not have the light trapped in the high refractive index ITO. Up to 50% of the light could be trapped in the organic/ITO waveguide mode combined. In order to extract the light trapped in ITO, the internal light out-coupling method has to be used, which requires more complicated process and becomes more difficult to be made on flexible substrate. By removing the high index ITO layer, the amount of the light trapped in the waveguide mode is significantly reduced. This is consistent with a recent simulation work51. When no out-coupling structure is used, ITO-OLEDs may have higher out-coupling efficiency due to a micro cavity formed by the high index ITO. However, graphene-OLEDs have higher efficiency when light extraction methods are used, as more light is available in the graphene-OLEDs structure ultimately.

Phosphorescent WOLED performance

The performance of phosphorescent WOLEDs on SLG is shown in Fig. 6. When coloured objects are illuminated by SLG-WOLED, they all exhibit vivid colour, indicating an effective WOLED device (Fig. 6a). The emission spectra of WOLEDs on SLG exhibit the blue, green and red emission peaks, similar to the control device fabricated on an ITO electrode (Fig. 6b). The colour rendering index is calculated to be 85. The emission spectra of the WOLED on ITO and on SLG are different due to the difference in light out-coupling. However, amounts of optical power coupled out are similar27.

(a) Photos of flexible SLG-WOLEDs and an high brightness SLG-WOLED illuminating coloured objects. (b) Emission spectrum of WOLEDs on SLG and ITO. (c) EQE of SLG-WOLEDs on various substrates with high index lens for enhanced light out-coupling. (d) PE and CE of SLG-WOLEDs and ITO-WOLEDs with enhanced light out-coupling. The error bars represent the s.d. of multiple measurement results.

Light-coupling methods including substrates and lenses made of ordinary glass (n=1.52), sapphire (n=1.74) and high index glass (n=1.80) were also used to further enhance the efficiency of SLG-WOLEDs and to confirm the high internal quantum efficiency. EQEs=51, 49 and 40% are demonstrated using high index glass, sapphire and ordinary glass, respectively (Fig. 6c, top three curves). Without light extraction, the EQE values at 3,000 and 10,000 cd m−2 are 17% and 14%, respectively (Fig. 6c, bottom three curves). The demonstrated WOLED efficiency is much higher than the previous report of WOLEDs on graphene. More importantly, the efficiency is high at a much enhanced brightness level, which is ~100 times higher than previously demonstrated WOLED on MLG. The high brightness performance makes our devices suitable for general lighting applications. Figure 6d shows that the PE of our SLG-WOLEDs reaches 90 lm W−1 at 1,000 cd m−2 and 80 lm W−1 at 3,000 cd m−2, comparable to other most efficient lighting technologies52.

Discussion

SLG-OLEDs using our device structure eliminate those drawbacks in ITO-based devices and achieve the record performance among all OLEDs using carbon-based transparent electrodes. The SLG-WOLEDs match other high brightness high-efficient lighting technologies, such as fluorescent tube, and inorganic LEDs. With the continuing optimization of device parameters and optical structures, SLG-OLEDs have the potential to exhibit even higher efficiency and brightness. Based on the calculations27,53, it is possible to reduce the sheet resistance of SLG to 40–60 Ω/□, which makes SLG suitable for large-area devices. SLG also has the potential to outperform ITO, in particular for future flexible devices on plastic substrates due to the process temperature limitation for ITO deposition on plastic substrates, where ITO can only achieve the sheet resistance of 60–100 Ω/□ at a transmittance of ~80% (ref. 54). Similar to the case of ITO, metal grids can also be incorporated to lower the overall resistance. It has been demonstrated that a fine metal grid on graphene can reduce its resistance to <10 Ω/□, while keep the similar film transparency55,56. It can be expected that by combining higher performance SLG electrodes with all the key findings presented in this work, such as low turn-on voltage, low series resistance, high current injection, low efficiency roll-off and high PE, large-area high brightness devices will become feasible. This work provides a potential solution for high performance, low cost and flexible display and lighting technologies.

Methods

Graphene synthesis and chemical doping

SLG used in this work was grown by a two-step chemical vapour deposition process using a copper (Cu) foil (25 μm, Sigma-Aldrich). The Cu foil was heated to 1,020 °C in 20 sccm forming gas (5% H2 in Ar) for 80 min to remove both the native surface oxide of Cu and increase the grain size of Cu. Subsequently, 1 sccm CH4 was introduced for 5 min, followed by 10 sccm CH4 for 35 min at the same temperature followed by cooling in 20 sccm forming gas to form graphene. PMMA was spin-coated on the graphene/Cu foil as a supporting membrane, and then the Cu foil was chemically dissolved in a Cu etchant (CE-200, Transcene). The remaining PMMA/graphene layer was rinsed with 10% HCl, and washed with deionized water, followed by transfer to a glass or plastic substrate. P-type chemical doping of graphene was performed by soaking the graphene sample in a 1 mg per ml triethyloxonium hexachloroantimonate (OA)/dichloroethene solution for 30 min.

Organic film growth and device fabrication

After doping the graphene samples were coated with 20 nm poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS), followed by a 120 °C bake on a hot plate for 20 min before organic material growth. The indium tin oxide (ITO) electrode was first cleaned by detergent and solvent, followed by 10 min exposure to UV/ozone treatment before the organic material deposition. The substrates are then loaded into vacuum chamber with base pressure of <5 × 10−7 Torr for film deposition by thermal evaporation. The film deposition for the phosphorescent green OLED structure includes a 2 nm-thick MoO3 anode interface layer, a 50-Å-thick CBP doped with 10% MoO3 hole injection layer, a 300-Å-thick CBP neat host layer, 150-Å-thick CBP doped with 7% bis(2-phenylpyridine)(acetylacetonate)iridium(III) [Ir(ppy)2(acac)] light emission layer, a 600-Å-thick TPBi electron transporting layer, a 10-Å-thick LiF electron injection layer and a 100 nm-thick Al cathode. The film deposition for the phosphorescent WOLED includes a 200-Å-thick CBP doped with a 10% MoO3 as hole injection layer, a 100-Å-thick CBP neat host layer, a 120-Å-thick CBP doped with 5% Ir(ppy)2(acac) and 5% bis(2-methyldibenzo[f,h]quinoxaline) (acetylacetonate) iridium (III) [Ir(MDQ)2(acac)] as the red emissive layer, 30-Å-thick CBP doped with 8% Ir(ppy)2(acac) as the green emissive layer, 75-Å-thick CBP doped with 20% bis(4,6-difluorophenylpyridinato-N,C2)picolinatoiridium (Firpic) as the blue emissive layer, a 650-Å-thick TPBi electron transporting layer and a 100 nm-thick Al/10-Å-thick LiF cathode. The OLEDs on ITO has the same structure were deposited at the same time of SLG-OLEDs.

Device characterization

Current–voltage (I–V) characteristics were measured using an HP4140B semiconductor parameter analyzer. Luminance-voltage (L–V) measurements were taken using a Minolta LS-110 luminance metre. The luminous flux for calculating the EQE and PE was measured using an integrating sphere (Supplementary Fig. S4) with a silicon photodiode with NIST traceable calibration. The device under test was mounted on the entrance aperture of the integrating sphere for all measurements. Measurements with out-coupling enhancement used a 10 mm diameter half-sphere lenses mounted on top of the device with index matching gel. The electroluminescence spectra were measured using an Ocean Optics USB4000 spectrometer. All the measurements were conducted in ambient air. We have reproduced the results for multiple devices on the same substrate and also for several repetitions of the same experiment.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Li, N. et al. Efficient and bright organic light-emitting diodes on single-layer graphene electrodes. Nat. Commun. 4:2294 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3294 (2013).

References

Tang, C. W. et al. Organic electroluminescent diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 51, 913–915 (1987).

Burroughes, J. H. et al. Light-emitting diodes based on conjugated polymers. Nature 347, 539–541 (1990).

Baldo, M. A. et al. Highly efficient phosphorescent emission from organic electroluminescent devices. Nature 395, 151–154 (1998).

Friend, R. H. et al. Electroluminescence in conjugated polymers. Nature 397, 121–128 (1999).

Shen, Z. et al. Three-color, tunable, organic light-emitting devices. Science 276, 2009 (1997).

Müller, C. D. et al. Multi-colour organic light-emitting displays by solution processing. Nature 421, 829 (2003).

Forrest, S. R. The path to ubiquitous and low-cost organic electronic appliances on plastic. Nature 428, 911–918 (2004).

D’Andrade, B. W. et al. White organic light-emitting devices for solid-state lighting. Adv. Mater. 16, 624–628 (2004).

Sun, Y. et al. Enhanced light out-coupling of organic light-emitting devices using embedded low-index grids. Nat. Photon. 2, 483 (2008).

Reineke, S. et al. White organic light-emitting diodes with fluorescent tube efficiency. Nature 459, 234 (2009).

Alzoubi, K. et al. Bending fatigue study of sputtered ITO on flexible substrate, IEEE. J. Display Technol. 7, 593–600 (2011).

Chen, Z. et al. A mechanical assessment of flexible optoelectronic devices. Thin Solid Films 394, 201–205 (2001).

Ellmer, K. Past achievements and future challenges in the development of optically transparent electrodes. Nat. Photon. 6, 809–817 (2012).

Solid State Lighting Manufacturing Roadmap, US Department of Energy (2011).

Lee, S. T. et al. Metal diffusion from electrodes in organic light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 75, 1404–1406 (1999).

Geim, A. K. et al. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183–191 (2007).

Kim, K. S. et al. Large-scale pattern growth of graphene films for stretchable transparent electrodes. Nature 457, 706–710 (2009).

Kasry, A. et al. Chemical doping of large-area stacked graphene films for use as transparent conducting electrodes. ACS Nano 4, 3839–3844 (2010).

Huang, X. et al. Graphene-based electrodes. Adv. Mater. 24, 5979–6004 (2012).

Schedin, F. et al. Detection of individual gas molecules adsorbed on graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 652–655 (2007).

Chen, J. et al. Intrinsic and extrinsic performance limits of graphene devices on SiO2 . Nat. Nanotech. 3, 206–209 (2008).

Zhu, W. J. et al. Graphene radio frequency devices on flexible substrate. App. Phys. Lett. 102, 233102 (2013).

Lee, S. et al. Enhanced charge injection in pentacene field-effect transistors with graphene electrodes. Adv. Mater. 23, 100–105 (2010).

Bae, S. et al. Roll-to-roll production of 30-inch graphene films for transparent electrodes. Nat. Nanotech. 5, 574–578 (2010).

Blake, P. et al. Graphene-based liquid crystal device. Nano Lett. 8, 1704–1708 (2008).

Park, H. et al. Doped graphene electrodes for organic solar cells. Nanotechnology 21, 505204 (2010).

Wu, J. et al. Organic light-emitting diodes on solution-processed graphene transparent electrodes. ACS Nano 4, 43–48 (2010).

Sun, T. et al. Multilayered graphene used as anode of organic light emitting devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 133301 (2010).

Han, T.-H. et al. Extremely efficient flexible organic light-emitting diodes with modified graphene anode. Nat. Photon. 6, 105–110 (2012).

Li, X. et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform graphene films on copper foils. Science 324, 1312–1314 (2009).

Han, S. J. et al. Graphene technology with inverted-T gate and RF passives on 200 mm platform. Int. Electron. Dev. Meet. 2011, 2.2.1–2.2.4 (2011).

Chandra, B. et al. Stable charge-transfer doping of transparent single-walled carbon nanotube films. Chem. Mater. 22, 5179–5183 (2010).

Dresselhaus, M. S. et al. Perspectives on carbon nanotubes and graphene raman spectroscopy. Nano. Lett. 10, 751–758 (2010).

Chen, C. F. et al. Controlling inelastic light scattering quantum pathways in graphene. Nature 471, 617–620 (2011).

Yan, J. et al. Electric field effect tuning of electron-phonon coupling in graphene. Phy. Rev. Lett. 98, 166802 (2007).

Li, Z. Q. et al. Dirac charge dynamics in graphene by infrared spectroscopy. Nat. Phys. 4, 532–535 (2008).

Helander, M. G. et al. Chlorinated indium tin oxide electrodes with high work function for organic device compatibility. Science 332, 944 (2011).

Shrotriya, V. et al. Transition metal oxides as the buffer layer for polymer photovoltaic cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 073508 (2006).

Li, N. et al. Open circuit voltage enhancement due to reduced dark current in small molecule photovoltaic cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 023307 (2009).

Kim, D. Y. et al. The effect of molybdenum oxide interlayer on organic photovoltaic cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 093304 (2009).

Kroger, M. et al. Role of the deep-lying electronic states of MoO3 in the enhancement of hole-injection in organic thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 123301 (2009).

Wang, Z. B. et al. Highly simplified phosphorescent organic light emitting diode with >20% external quantum efficiency at >10,000 cd/m2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 073310 (2011).

Greiner, M. T. Universal energy-level alignment of molecules on metal oxides. Nat. Mater. 11, 76–81 (2012).

Wang, X. et al. Atomic layer deposition of metal oxides on pristine and functionalized graphene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 8152–8153 (2008).

Xuan, Y. et al. Atomic-layer-deposited nanostructures for graphene-based nanoelectronics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 013101 (2008).

Kim, Y. H. et al. Highly conductive PEDOT:PSS electrode with optimized solvent and thermal post-treatment for ITO-free organic solar cells. Adv. Function. Mater. 21, 1076–1081 (2011).

Adachi, C. et al. Nearly 100% internal phosphorescence efficiency in an organic light-emitting device. J. Appl. Phys. 90, 5048 (2001).

Wang, Q. et al. Manipulating charges and excitons within a single-host system to accomplish efficiency/CRI/color-stability trade-off for high-performance OWLEDs. Adv. Mater. 21, 2397–2401 (2009).

Giebink, N. C. et al. Quantum efficiency roll-off at high brightness in fluorescent and phosphorescent organic light emitting diodes. Phys. Rev. B 77, 235215 (2008).

Okumoto, K. et al. High efficiency red organic light-emitting devices using tetraphenyldibenzoperiflanthene-doped rubrene as an emitting layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 013502 (2006).

Kim, S.-Y. et al. Outcoupling efficiency of organic light emitting diodes employing graphene as the anode. Organ. Electron 13, 1081 (2012).

Lighting technologies: a guide to energy efficient illumination, from energystar.gov.

De, S. et al. Are there fundamental limitations on the sheet resistance and transmittance of thin graphene films? ACS Nano 4, 2713 (2010).

Sigma-aldrich product catalogue (2013); Nanocs product catalog (2013).

Zhu, Y. et al. Rational design of hybrid graphene films for high-performance transparent electrodes. ACS Nano 5, 6472 (2011).

Kasry, A. et al. High performance metal microstructure for carbon-based transparent conducting electrodes. Thin Solid Films 520, 4827–4830 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Zhibin Wang, Jacky Qiu, Michael Helander and Zheng-Hong Lu at University of Toronto, and Yifan Zhang and Stephen Forrest at University of Michigan for helpful discussion and experimental assistance. We also thank Fengnian Xia, Hugen Yan, Cheng-Wei Cheng, Kuen-Ting Shiu, John Yurkas, Ali Afzali-Ardakani, Christos Dimitrakopoulos, Dennis Newns and Ghavam Shahidi at IBM Research for helpful discussions and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.L. designed and performed all the study, collected the data and wrote the manuscript. S.O. contributed to graphene synthesis. G.S.T. contributed to graphene doping process. S.-J.H. contributed to graphene processing and manuscript proofreading. J.B.H. contributed to film deposition process. D.K.S. and T.-C.C. managed the project. All authors participated in the discussion.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S5, Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary References (PDF 298 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, N., Oida, S., Tulevski, G. et al. Efficient and bright organic light-emitting diodes on single-layer graphene electrodes. Nat Commun 4, 2294 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3294

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3294

This article is cited by

-

Preparing the photo- and heat-stable PGMA/CdTe quantum dot composite films and exploring devices for LED-display poster design

Chemical Papers (2024)

-

Stably doped graphene transparent electrode with improved light-extraction for efficient flexible organic light-emitting diodes

Nano Research (2023)

-

Organic white-light sources: multiscale construction of organic luminescent materials from molecular to macroscopic level

Science China Chemistry (2022)

-

Improved Performance of Organic Light-Emitting Diodes Based on Oligomer Thin Films with Graphene

Journal of Electronic Materials (2020)

-

Effects of hemicellulose content on TEMPO-mediated selective oxidation, and the properties of films prepared from bleached chemical pulp

Cellulose (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.