Abstract

Chromosomal rearrangements are mutations contributing to both within and between species variation; however their contribution to fitness is yet to be measured. Here we show that chromosomal rearrangements are pervasive in natural isolates of Schizosaccharomyces pombe and contribute to reproductive isolation. To determine the fitness effects of chromosome structure, we constructed two inversions and eight translocations without changing the coding sequence. We show that chromosomal rearrangements contribute to both reproductive success in meiosis and growth rate in mitosis with a strong genotype by environment interaction. These changes are accompanied by alterations in gene expression. Strikingly, we find several examples leading to antagonistic pleiotropy. Even though chromosomal rearrangements may have a deleterious effect during sexual reproduction, some compensate with a strong growth advantage in mitosis. Our results constitute the first quantification of fitness effects caused by de novo mutations that result in chromosomal rearrangement variation and suggest a mechanism for their maintenance in natural populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The first chromosomal rearrangement (CR) segregating in natural populations was described by Dobzhansky and Sturtevant1 in Drosophila pseudoobscura. Genomes are now known to be far more fluid than was considered previously. CRs are widely distributed between species2,3 and within species where they segregate as polymorphisms4,5. In humans, an increasing number of polymorphic variation for CRs is described in the literature6. One particular form of CRs, inversions, is often associated with adaptation to specific environments as observed in D. pseudoobscura7, Anopheles gambiae8 and Mimulus guttatus9. The ubiquity of CRs and their consequent low hybrid viabilities10 and reduced gene flow in heterozygotic crosses7,11 has also led to the proposal that CRs serve as an initial genetic barrier in eukaryotic speciation12,13,14,15,16.

In the well-documented cases of Drosophila and Anopheles, the frequency of CRs in the population varies clinally and/or seasonally, suggesting that the beneficial effects are caused by chromosome inversions. Several traits have since been associated with inversion polymorphisms17,18, indicating that they can influence the evolution of these populations. Yeast karyotypes have also been extensively characterized and similarly exhibit numerous CRs19. As an example, natural and industrial populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae show remarkable chromosomal diversity20. In experimental evolution studies, the appearance of recurrent genomic rearrangements suggests that they increase fitness and are thus adaptive to laboratory conditions21,22. In most cases, growth advantages are caused by promoter modifications mediated either by reciprocal translocations that result in overexpression of metabolic genes23 or duplication of genes important for specific growth conditions24. Thus, changes in fitness are often accompanied by changes in gene expression. In Drosophila, different allozymes have been associated with particular chromosome inversions25, suggesting that gene expression differences are linked to these chromosomal configurations. Other examples of gene expression variation are caused by transposons26, gene duplications27 and aneuploidies28. However, it is currently unknown whether the expression pattern is a direct consequence of structural variation per se or other nucleotide variation or a combination of both.

Even though ample evidence exists for a direct role of CRs in adaptation, it is difficult to disentangle the contribution of gene alterations from their impact in chromosome structure as both often occur simultaneously. In this context, a key contribution by Colson et al.29 demonstrated that two naturally occurring translocations may have been fixed between S. mikatae and S. cerevisiae by positive selection. The two reciprocal translocations of S. mikatae were ‘reconstructed’ in the S. cerevisiae genome in the absence of other polymorphisms and shown to provide growth advantages for S. cerevisiae in different environments. Thus, CRs can provide selective advantage in the absence of other forms of genome alterations.

The results of Colson et al.29 support a model where natural selection is responsible for the fixation of CRs between yeast species. However, the CRs tested in this study were naturally occurring and so we may expect them to be either neutral or advantageous, as strongly deleterious CRs are unlikely to be fixed in natural populations. Thus, the fundamental question remains to be answered: what are the fitness consequences of varying chromosome structure?

Here we use the model organism S. pombe to investigate the phenotypic consequences of CRs that were engineered to mimic possible spontaneous mutations that only alter genome structure. Ten CRs, not previously tested by natural selection, were assayed for meiotic and mitotic fitness to unravel the contribution of CRs to population fitness variation across environments. We show that CRs display variation for both types of fitness measures and that they can be maintained in nature by a phenomenon called antagonistic pleiotropy.

Results

Natural chromosomal diversity impairs sexual reproduction

S. pombe is an established model system for cellular and molecular biology due to its ease of genetic manipulation and conserved chromosomal organization. It has a small genome of ~14 Mbp distributed in three chromosomes of 5.7, 4.6 and 3.5 Mbp (ref. 30). As a result, S. pombe is a suitable organism to study the impact of chromosome structure in environmental adaptation and evolution.

Given the importance and wide distribution of CRs in several species, we started by characterizing 10 natural isolates from different geographic regions (Supplementary Table S1). L972 is the most widely used strain and the first to have its genome sequenced, thus we considered it as the reference genome. We analysed the karyotypic profile by whole-chromosome pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and NotI restriction-PFGE followed by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 1a–c; Supplementary Figs S1–S3). Both whole chromosomes and NotI fragment sizes revealed a remarkable diversity for chromosome structure (Fig. 1d). In our small sample size, we have observed two independent translocations (NCYC132 and ATCC2476), a large inversion common to all except for L972 and other uncharacterised smaller intrachromosomal variations.

(a) Whole-chromosome PFGE analysis of S. pombe chromosomes. L972 reference strain contains three chromosomes: Chr. I 5.7 Mb, Chr. II 4.6 Mb and Chr. III 3.5 Mb. (b) PFGE of chromosomal DNA digested with NotI reveals different restriction patterns for each strain. The differences are not due to NotI polymorphisms, as all 13 are present and recognized by NotI enzyme (Supplementary Fig. S1). (c) Localization of NotI restriction sites in reference strain L972. (d) Schematic representation of the three chromosomes in the different strains. Only the minimal CRs detected are represented (see Supplementary Figs S2 and S3). These were mapped using chromosome-specific probes present at different positions, including the centromere-specific region imrL (imrL1, imrL2 and imrL3). Symbols in A1153, A1263 and A826 represent other not fully characterized CRs. (e) Meiotic viability of natural isolates. Each cross represents the analysis of 14–43 tetrads (containing the four meiotic products). Intervals correspond to 2 × s.e. for a binomial distribution.

We examined whether the observed chromosome variation was reflected at the sequence level. We measured a maximum local nucleotide diversity of 6.8 × 10−3 (Table 1) that is similar to the one found in a recent study using ca. 80 fission yeast natural isolates31. Both these and our results were corroborated by whole-genome quantification of nucleotide diversity performed in S. pombe32. Specifically, Rhind et al.32 estimated 8.9 × 10−3 nucleotide diversity from pairwise comparison of L972 and NCYC132 strains. This value is close to the one measured in worldwide populations of S. cerevisiae (5.6 × 10−3) (ref. 33). Thus, not only do CRs appear to be pervasive in natural populations of S. pombe but, unpredictably, they keep nucleotide diversity levels close to those observed within-species (Fig. 1; Table 1).

We next tested the genetic isolation between the natural isolates by scoring hybrid viabilities in pairwise crosses analysed by tetrad dissection. S. pombe is generally homothallic, implying that it is capable of switching between mating types and inbreeding. In order to directly measure genetic isolation, we required strains that stably express opposing mating types and so we disrupted the minimal sequence required for switching (Supplementary Fig. S4)34. Expectedly, crosses within the same natural isolate showed high meiotic viability (>80%, Fig. 1e). Different isolates from the same geographical location, which exhibit similar karyotypes, showed low levels of reproductive isolation (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Table S1). However, in spite of low genetic diversity, hybrid viability decreased sharply when we compared strains of different karyotypes (see L972 and NCYC132 as example; Fig. 1e). These results point to CRs acting as genetic barriers, leading to low viability of hybrids. Consistently, CRs are considered early events for genetic isolation in chromosomal speciation models16.

Artificial CRs affect meiotic viability

It would be impossible to attribute the lower hybrid viability to CRs alone as all natural isolates possess further genetic differences. In addition, these CRs are a product of natural selection and therefore biased in their diversity. For this reason, we devised a set of newly generated yeast strains with unbiased CRs departing from a single genetic background. We produced two pericentric inversions and eight reciprocal translocations encompassing the three chromosomes using a Cre-loxP system developed by Molnar and Kleckner35 (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. S5). Our engineered strains are identical in their coding sequence, thus allowing us to investigate how chromosome structure affects fitness in an unbiased way. To control for non-specific Cre-loxP events, CRs were generated at least twice from each parental strain. We observed that all replicate CRs behaved identically, so we used them as replicates and averaged their results.

(a) Schematic representation of karyotypes for 10 different genetically engineered S. pombe strains. All the strains are isogenic except for the rearrangement and its breakpoint. Chromosomes are drawn to scale. Inflexions represent the centromeres. To generate the CR strains, Cre recombinase was expressed in parental strains using a plasmid and selecting for two colonies, each representing a totally independent recombination event. (b) Meiotic viability of homozygotic and heterozygotic crosses. CRs reduce meiotic viability in heterozygotic crosses from 8 to 48% with the exception of T8 that exhibits no apparent reduction. Meiotic viability corresponds to the number of viable haploid spores that have formed a colony divided by the total number of spores. Each cross represents the analysis of 18–63 tetrads. Error bars represent 2 × s.e. for a binomial distribution. P—parental strain; R—rearranged strain. (c) Frequency of recombination between loci at the breakpoints and the mat1 locus. Inversions suppress recombination between any of the breakpoints and the mat1 locus by ~30%. In contrast, translocations do not significantly reduce recombination frequency. Only rearrangements involving chromosome II were scored. Error bars correspond to 2 × s.e. for a binomial distribution.

In order to test the meiotic fitness of artificial CRs, we performed pairwise crosses of parental with parental (P × P), parental with rearranged (P × R), and rearranged with rearranged (R × R) strains and quantified them by tetrad analysis. Offspring resulting from homozygotic crosses (P × P and R × R) were largely viable (Fig. 2b). The drop in viability for heterozygotic crosses (P × R) involving the two inversions was ~40%. Similarly, heterozygotic crosses involving translocations T3, T5, T6, T9 and T10 had losses in hybrid viability of 30–48%. Surprisingly, P × R crosses involving T8 did not lead to appreciable meiotic depression (Fig. 2b). As expected, meiotic recombination was unperturbed in homozygous crosses P × P but not in heterozygous crosses involving inversions (Fig. 2c). Overall, we observed genetic linkage of loci residing near the breakpoints of all the tested inversions and translocations (Supplementary Fig. S6). Our results support previous observation for the reduction of gene flow inside pericentric inversions in Drosophila36.

CRs are a selectable trait

How can CRs be maintained as polymorphisms in nature if they impair meiosis? One possibility could be the occurrence of antagonistic pleiotropy during their life cycle, such that a given CR is disadvantageous in one part (meiosis) but then compensated by an advantageous trait in another (mitosis). To quantify mitotic fitness of the newly generated CRs, we performed competitive assays as described by Desai et al.37 Briefly, the rearrangement and its parental ura4+ strain were competed against a control expressing GFP. The effect of the GFP was subsequently removed by subtracting the two selective coefficients (ΔS):

Details of the essay and calculations can be found in the Supplementary Information. We observed substantial variation for fitness associated with chromosome structure during the asexual life cycle in S. pombe (Fig. 3a). As an example, strains T6 and T9 exhibited growth advantage of 3% per generation when competed with the parental strain in rich medium (YES). In contrast, T5 and T8 showed growth disadvantage of 1.5% per generation. Strikingly, CRs can have very strong effects, either deleterious or beneficial even in a benign environment such as rich medium.

(a) Selective coefficients relative to the parental ura4+ strain grown in rich media (YES) with and without 3% EtOH. Some CRs improve fitness relative to the parental, others are neutral or deleterious. Averages were calculated from >10 independent experiments each with two independent clones. These clones were generated by independent Cre-loxP recombination events to minimize additional mutations and off-target effects. Error bars represent 2 × s.e. (***P<0.001, **P<0.01 and *P<0.05 according to Mann–Whitney U-test). (b) Mitotic fitness in multiple environments of strains containing CRs. Modified strains display strong genotype by environment interactions. Selection coefficients are relative to parental ura4+ strain. Coloured boxes represent average selection coefficient of designated CRs in each environment according to the scale represented at the bottom. Averages were calculated from >10 independent experiments each with two independent clones. Environments were ordered by increased variance in fitness.

As fitness effects are expected to change under different types of stress, we sought to assess fitness in several growth conditions. All of them, with the exception of YES, were suboptimal for the growth of a wild-type strain (Supplementary Fig. S7). We additionally tested different carbon sources and other abiotic factors, such as low pH and increased temperature, mimicking environments that yeast may experience during fermentation. Our results show that, similar to other types of mutations, fitness effects conferred by CRs vary according to the environment in which they grow (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. S8). The same rearrangement could be strongly beneficial in one environment but deleterious in another, exhibiting therefore genotype-by-environment interactions (Fig. 3b). Thus, our observations indicate that CRs not only affect growth but also they can be deleterious or beneficial depending on the environment that they are exposed.

Antagonistic pleiotropy can maintain chromosomal diversity

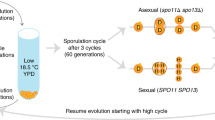

Next we tested directly whether advantageous CRs were always destined for fixation or whether their associated meiotic depression could keep them as polymorphism in the population via antagonistic pleiotropy. For this purpose, we devised an experiment where we mixed strains of both mating types either containing the CR or a GFP marker. We evolved these populations by serial passage under two growth conditions (Fig. 4a). Mixed populations were propagated either under an exclusively asexual life cycle (no mating), where the frequencies of the two genotypes would reflect their mitotic fitness differences, or a life cycle that included both asexual and sexual reproduction (with mating). We then tested for the maintenance of polymorphism of the CR under the two different environments, where it previously exhibited mitotic fitness advantage over its parental-GFP strain. We initiated these evolution tests introducing the CR at an initial frequency of ~25%, so that most crosses involving the CR strain were likely to be heterozygous. This way, we intended to mimic what may happen to an adaptive CR shortly after its appearance. As expected, in the absence of mating, the CR increased in frequency (Fig. 4b). If no other event takes place (such as de novo mutation), the CR would be expected to sweep through the population in a few hundred generations. However, when sexual reproduction occurs, the fixation of the CR was halted and its frequency was kept close to its initial levels (Fig. 4b; Supplementary Fig. S9). Thus, alternating the mode of reproduction prevented the extinction of the less-favoured genome configuration through antagonistic pleiotropy.

(a) Scheme of the evolution assay. The rearrangement T4 was mixed with its parental ura4+ marked with GFP (Control-GFP) at a frequency of 25%. The mixture was evolved asexually for 3 days or 15 mitotic generations (no mating). In parallel, the same mixture was first grown in ME to induce random mating and meiosis (With mating). Meiotic products were germinated and further propagated for 15 generations of mitotic growth. Additional details can be found in the Supplementary Information. (b) Frequency of the rearrangement and Control-GFP strains in competition experiments. The graph represents the average of at least four replicates, which are displayed in supplementary Fig. S9. The top graphs show evolution in YES while the bottom graphs in YES+3% EtOH. Both environments are beneficial for the CR in relation to Control-GFP strain.

One of the most important factors determining whether or not a CR is maintained in the population is the frequency of the rearrangement at the time of mating. A CR with a very large mitotic advantage is likely to reach frequencies of >50% and hence not pay any meiotic cost. In general, the maintenance of polymorphism or the fixation of one karyotype depends on the balance of the mitotic advantage, the meiotic depression and the frequency of CRs at the time of mating. We explored some of these effects in Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. S10. Given the effects of these variables, small demographic differences are likely to lead to very different outcomes in subpopulations exposed to the same environmental conditions, which may further contribute to the variability observed in natural S. pombe populations.

CRs alter gene expression

What was the basis of the growth differences in isogenic CR and parental strains? CRs confer structural changes to chromosomes that contribute to growth variability. In budding yeast, chromosome length is known to influence mitotic segregation and cell division38. Chromosomal size can also influence topological stress induced by DNA replication39. Thus, chromosome stability and, consequently, fitness is influenced by chromosome length. In order to test this hypothesis, we analysed strains containing the largest (6.96 Mb) and the smallest (1.93 Mb) chromosomes generated by this work (T7 and T8 respectively, Fig. 2a; Table 2). If both topological stress and segregation stability were translated into slower growth, we would expect strains carrying longest chromosomes to have deleterious phenotypes even in rich media. However, T7 and T8 have overall opposite results for fitness in most tested conditions (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. S8), arguing that chromosome size is not the major factor behind our observations. In addition, translocations where chromosome size is not significantly altered, such as T5, exhibit some of the most deleterious fitness effects (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. S8).

As all strains are isogenic, we hypothesized that fitness differences observed during asexual reproduction were caused by differences in gene expression near the breakpoints. The sites of recombination were introduced using an antibiotic resistance cassette (Kanr) that confers resistance to geneticin and can be used to assay for gene expression (Fig. 5a). Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that rearrangements respond differently to increasing amounts of geneticin (Fig. 5b). To directly evaluate differential gene expression near the breakpoints, we quantified mRNA levels of genes surrounding T5 and T7 (Fig. 5c,d). Out of four genes measured, expression of mrpl16+ was altered upon genome rearrangement (Fig. 5d). Together, our results indicate that CRs can lead to differences in gene expression near breakpoints.

(a) Cre-loxP recombination scheme. Recombination between the promoter construct (padh1-loxP-kanMX6) and the gene construct (loxP-ura4-kanMX6) results in the formation of the rearrangement and ura4+ expression. Black and grey boxes represent loxP sequences and circles indicate centromeres. (b) T5 and T7 have lower expression of the antibiotic resistance gene Kanr inserted near the breakpoint. Serial dilutions were spotted on plates containing 0, 100, 200 and 400 mg l−1 of geneticin and allowed to grow for 4 days at 32 °C. (c) Schematic representation of genes near the breakpoints in the parental strain and their localization in T5 and T7. (d) CRs cause changes to expression of genes near breakpoints. mRNA levels relative to controls near the breakpoint. Gene expression was assayed in cells that have grown in rich media (YES). Error bars represent s.e. of three to six independent experiments. (*P<0.05 according to Mann–Whitney U-test). (e) Schematic representation of genes involved in responses to general stress in S. pombe45 and to ethanol stress in S. cerevisiae44 in the parental strain and in T5 and T7. (f) Rearrangements cause changes in gene expression. T5 has lower gene expression upon exposure to 3% EtOH, whereas T7 is higher even before ethanol exposure. Genes are displayed by no particular order. Error bars represent s.e. of three to six independent experiments. Error bars represent s.e. (*P<0.05, **P<0.01 according to Mann–Whitney U-test). In applying the very conservative Bonferoni correction, there is not enough power to detect statistical significance in our gene expression studies.

We then reasoned that fitness effects of individual CRs in response to multiple environments could be accompanied by differences in gene regulation beyond the breakpoints. There are several lines of evidence in the literature for the importance of chromosomal environment for gene expression40. For instance, studies comparing gene expression data from humans and chimpanzees highlight the importance of the alteration in genomic neighbourhoods as a factor that contributes to changes in gene expression levels41. Positional effects such as these can be translated into morphological and/or physiological variation with major implications for evolution42. Similarly, modifications in gene order and position by means of CRs should interfere with patterns of gene expression. To obtain direct evidence for this pattern, we selected two strains with opposing responses to 3% EtOH, a naturally occurring but restrictive environment for a fermenting organism such as fission yeast (Fig. 3b)43. Using qRT-PCR, we measured mRNA levels of the genes involved in stress and ethanol responses representative of different chromosomal locations44,45. Analysis of 21 genes revealed that not only gene expression was different between T5 and T7 exposed to 3% EtOH but, in some cases, these alterations preceded the environmental change (Fig. 5e; Supplementary Fig. S11). Strikingly, we found gene expression changes to occur in loci located several kilobases away from the breakpoint and even on different chromosomes (Fig. 5e). We were able to measure differences in gene expression in chromosomes that were not involved in the translocation, suggesting that CRs affect trans regulation and are therefore not restricted to the breakpoint area.

Discussion

Mating and meiosis are crucial evolutionary traits of yeasts in the wild. Not only they provide for new variants via chromosome assortment and recombination but also are tightly linked to the production of resistance spores under nutritional stress. As such, we expected that deviations to the predominant chromosome type would be lost shortly after their appearance. Surprisingly, we found extensive karyotype variability in natural populations of S. pombe. This led us to search for a mechanism that allows the maintenance of variation for chromosome structure. We produced new artificial CRs that do not disrupt the coding sequence and found significant differences in terms of their competitive fitness under mitotic growth. Despite encompassing large chromosome segments and thus affecting many genes, some CRs were beneficial, whereas others were neutral or deleterious. CRs that were beneficial during mitotic growth but had a meiotic cost constitute examples of antagonistic pleiotropy—whereby an allele (in this case a chromosome structure) is deleterious in one part of the life cycle (when mating at low initial frequency) and beneficial in another (asexual reproduction). In addition, the mitotic advantage of the rearrangements varies greatly with the environment, showing genotype-by-environment interactions. Thus, we propose that antagonistic pleiotropy provides a mechanism for karyotype diversity in natural populations.

Although we understand well how the production of unbalanced chromosomes leads to the meiotic depression of rearrangements, mitotic advantages are more difficult to explain. We expect that changes in gene expression are likely to cause fitness variation among the different CR-containing strains. Thus, we favour a model whereby CRs disturb both cis and/or trans regulation, leading to variation in gene expression throughout the genome. It has been previously suggested that genomes are non-randomly arranged within the nuclear space forming chromosomal territories and giving rise to genomic neighbourhoods40. The nucleus has distinct structural and functional compartments and individual chromosomes can change their occupancy in the nucleus in order to accommodate specific expression profiles40. There is growing evidence that nuclear reorganization of chromosomes contributes to gene regulation caused by alterations in the relative position of genes to regulatory regions. One such example comes from studies in sensory neurons where the choice for expression of a particular odorant receptor results from the interaction of a single trans-acting enhancer element in chromosome 14 with the selected receptor in another chromosome46. Translocations and inversions change the localization and order of genes that can have profound effects on their expression. The three-dimensional (3D) configuration and chromosome dynamics are likely to change upon genome modifications. These alterations can cause modifications in gene expression by placing genes in a completely different constitutive heterochromatic or euchromatic region47 or separating them from specific regulatory elements48. It is not currently known whether this type of long-range transcriptional regulation occurs in S. pombe. Such effects may even be negligible in fission yeast due to its small genome size and the fact that gene proximity is not always a requisite for coexpression49. Nonetheless, the CRs engineered by us are likely to modify the normal nuclear localization of genes (especially those closer to centromeres, telomeres and rDNA clusters) and possibly their heterochromatic state and, consequently, expression level.

Another topic of current debate in the literature is the organization of genes into functional clusters likely maintained by natural selection50. Genome-wide expression studies in several organisms have shown that genes with similar expression patterns are arranged into clusters51,52. The expression of genes in these clusters is coordinated as the pattern of gene expression is similar for proximal genes52,53. Although the conservation of gene order appears to be the result of natural selection50, it is not clear that it is always associated with gene expression changes and related to functional constraints54. A recent study looking at gene expression in Drosophila male testis has shown that, at least for certain clusters of genes, disruption of gene organization does not lead to phenotypic alterations and that the cluster organization of genes is not necessary to achieve standard and coordinated gene expression levels49. One important difference in our work is that we have not disrupted any known gene cluster and, despite this, we observed substantial phenotypic diversity associated with small-scale gene expression differences.

Overall, our results highlight the importance of genome architecture for fitness and establish a direct contribution of chromosome structure and gene organization. Using S. pombe as a model system, we show that variation in genome structure has fitness consequences as important as typical nucleotide changes. Our studies suggest that certain CRs may be maintained as polymorphisms in nature despite their low meiotic viability in heterozygotic crosses. Disadvantages in sexual cycle can be overcome by CR-dependent advantageous effects during asexual growth. Likewise, disadvantages in one environment can be balanced by advantages in another. These constitute unsuspected mechanisms of antagonistic pleiotropy capable of maintaining chromosome diversity in mixed populations. CRs can be fundamental for the generation of biological diversity at the karyotype level and may constitute a building block for further differentiation.

Methods

Strains and media

The strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Tables S1, S2. Standard media and growth conditions were used throughout this work55 with minor modifications: arginine and lysine were added to all media and NH4+ was used at a final concentration of 225 mg l−1 in all EMM-based media. Cultures were grown in rich media (YES) or minimal media (EMM) at 32 °C with shaking, unless otherwise stated. Tetrad dissection for meiotic viability analysis was performed on YES solid media.

Construction of a non-exchangeable mating type cassette

In order to fix the mating type in natural isolates, a stable non-switchable mat1 locus was constructed both for mat1-P and mat1-M as described previously34. Briefly, the pFA6a-natMX6 plasmid was used as backbone for the insertion of fragments PCR1 and PCR2 (Supplementary Fig. S4). Sequences of mat1-M, mat1-P, H2 and H1 were taken from Kelly et al.56 PCR1 and PCR2 products were amplified from pON104 (mat1-P) and pON107 (mat1-M) plasmids, kindly provided by Olaf Neilsen (University of Copenhagen). The final constructs, pcr1P-natMX6-pcr2P and pcr1M-natMX6-pcr2M, were used to transform homothallic S. pombe. To confirm loss of the switching capacity, strains were plated in maltose extract agar (ME) for 3 days and checked for the absence of mating and meiotic products.

Meiotic viability

Meiotic crosses were executed as described in Moreno et al.55 Tetrad dissections were performed on YES plates in a micromanipulator equipped with a glass needle (Singer Instruments). Meiotic viability is given as the number of colonies formed by each meiotic product divided by the total number of colonies expected.

Pulse-field gel electrophoresis

PFGE was performed as described by Ferreira and Cooper57 using exponentially growing cells (0.5–1 × 107 cells per ml) in YES media. All PFGE were performed on a Biorad CHEF-DR III System. DNA was visualized by ethidium bromide staining and gels were processed for Southern blotting.

Southern blot analysis

Southern blot analysis was performed as described by Ferreira and Cooper57. Different probes were labelled with 32P-dCTP using the Prime-it II random primer labelling kit (Stratagene). Probes were generated by PCR amplification (Supplementary Table S3).

DNA sequencing and alignment

Colony PCR was performed to obtain genomic DNA for PCR amplification (Supplementary Table S3). Genetic sequences were amplified with Roche PCR master mix (Roche) and purified with Promega Wizard SV Gel and PCR clean up system. DNA sequencing was performed according to the manufacter’s instructions using the BigDye Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems). Analysis of DNA sequences and their quality were performed using 4Peaks and DNAStrider software, respectively. DNA sequence alignment was performed in MUSCLE from EBI and π values calculated using DnaSP58.

Construction of CR strains

For parental strains, different combinations of Molnar and Kleckner’s35 strains were crossed to obtained different haploid strains with selected combination of the loxP cassette at the auxotrophic marker (Supplementary Fig. S2; Supplementary Table S2). MGF1070 and MGF2098 were generated by protoplast fusion of strains MGF539 and MGF542 as described by Gingold59. For sporulation of the diploids, cells were transformed with the pON104 plasmid. With the exception of MGF1070 and MGF2098, all strains were transformed independently with mat1-M and mat1-P fragments to fix their mating types. Strains were selected based on the simultaneous presence of padh1-loxP-kanMX6 and loxP-ura4-kanMX6 fragment after PCR amplification. These strains are referred to as parental strains. For generation of rearranged strains, parental strains were transformed with pREP81-Cre or pREP81 plasmids and plated directly in selective media EMM–leu with 4 mM thiamine. Single colonies were inoculated overnight in liquid media EMM–leu and plated in EMM–ura 18/20 h after for selection of the recombination event. Single colonies were then re-streaked into EMM–ura and then to YES and genotyped. We selected two colonies, each representing a totally independent recombination event. All the strains were frozen immediately as soon as the genotype was confirmed. Cells were exposed to the minimum possible time to the Cre recombinase, by promoting the loss of the pREP81–Cre plasmid straight after the recombination event. As parental strains are ura4− and CRs are ura4+, we obtained equivalent strains ura4+ (termed Parental ura4+ strains) to use in competition assays. To generate these strains, the same parental cells that were used for pREP81-Cre transformation were crossed with strain L972 or another prototrophic strain. GFP tagged cells were created by insertion of 3nmt1-GFP-hphMX6 fragment60 near the breakpoint loci (Supplementary Table S1).

Competitive fitness assays

To measure the fitness effects of CRs, we developed a FACS-based competitive assay. Unlabelled CR strain and Parental ura4+ strain were independently competed against its reference GFP-labelled strain (Control-GFP, Supplementary Fig. S2). To do so, both CR and control strain were grown in YES liquid medium for 24 h at 32 °C with aeration and shaking. The following day cultures were diluted and, once in mid-exponential phase, mixed at 1:1 ratios with the fluorescently labelled control strain with total initial cell density in the order of 2 × 105 cells per ml. The effective ratio of the mixture was measured using FACS. Then, 600 μl of the mix was placed in a 96-deep-well plate and incubated in a mini-shaker (VWR) at 32 °C with 850 r.p.m. agitation. Unless otherwise stated, cells were grown at 32 °C. Every 24 h cells were diluted 1:30 to fresh media. This was repeated three times. After 4 days (~20 generations), final ratios of unlabelled to GFP-labelled strain were measured. The number of GFP-positive (reference) and non-fluorescent (experimental) cells was determined using a Cyan ADP Cell Analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.) counting 10,000 total cells for each sample. Selection coefficients (ΔS) were calculated as:

with t0 the initial time (zero generations) and tf the final time (20 generations). In order to obtain the selection coefficient of the rearrangement, we extracted the weight of the GFP, such that the final selection coefficient is given by:

The selection coefficient was estimated as an average of at least 20 independent competition assays.

Assaying for antagonistic pleiotropy

T4, T10 and their respective controls were transformed as described above to create the set of four strains used in the experiment: h− CR, h+ CR, h− Control-GFP and h+ Control-GFP. These strains were grown separately two overnights in either YES or YES+3% EtOH. Then, h− CR and h+ CR were mixed in equal proportions, and the same was done for the control-GFP strains. Finally, the CR mix and control-GFP mix were mixed such that the CR was at a low frequency (~20%). The frequencies were measured by flow cytometry using an LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences), producing point 0 in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. S6. Here the mixtures were split in two different plates. A 96-deep-well plate with either YES or YES+3% EtOH and a ME 96-well plate. The first plate corresponds to the CR dynamics without mating and was incubated at 32 °C during 24 h, at which point the cells were diluted into fresh medium and their frequency measured. This was done over 3 days. The second plate corresponds to the mating scenario and was incubated at 25 °C for 3 days, when tetrad production was checked. Spores and cells were harvested and incubated in water with 1% Hellix pomatia extract at room temperature for 16 h to digest all vegetative cells and release the spores. The spores were washed in water and resuspended in YES, incubated overnight at 32 °C and then diluted (20–600 μl) in either YES or YES+3% EtOH. This was repeated for 3 days.

qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression

Total RNA was isolated from exponentially growing cultures of each strain using a RiboPure-Yeast kit (Ambion). Gene expression was assayed in cells that have grown in YES and after 15- or 30-min exposure to 3% EtOH. Synthesis of cDNA was performed using MMLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega). Quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s instructions. All qPCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 10 μl, three replicates per sample (technical replicas), and set up in a 384-well plate. Quantitative DNA amplification was carried out in the ABI 7900 HT machine (Applied Biosystems). Reporter signals were analysed using SDS 2.4 software (Applied Biosystems). The CT value of the gene coding for actin (act1+) was used for the normalization of variable cDNA levels and induction factors were determined for each gene and condition.

Growth assays

Strains were grown overnight in YES in a volume of 600 μl per well in 96-deep-well plates. The following day, cells were diluted 1:30 to the appropriate media and time points were recorded approximately every 2 h. Cell OD was measured in a final volume of 100 μl in 96-well flat bottom at 600 nm in Victor III apparatus (Perkin Elmer).

Viability assays

Drug sensitivity analysis was performed as described55. Briefly, exponentially growing cells in YES media were collected and counted. Five-fold serial dilutions from a starting concentration of 1 × 107 cells per ml are prepared and 5-μl spots of the serial dilutions are spotted into the specific media containing agar plate.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Avelar, A. T. et al. Genome architecture is a selectable trait that can be maintained by antagonistic pleiotropy. Nat. Commun. 4:2235 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3235 (2013).

References

Dobzhansky, T. & Sturtevant, A. H. Inversions in the chromosomes of Drosophila pseudoobscura. Genetics 23, 28–64 (1938).

Bourque, G., Pevzner, P. A. & Tesler, G. Reconstructing the genomic architecture of ancestral mammals: lessons from human, mouse, and rat genomes. Genome Res. 14, 507–516 (2004).

Liti, G. & Louis, E. J. Yeast evolution and comparative genomics. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59, 135–153 (2005).

Hoffmann, A. A. & Rieseberg, L. H. Revisiting the impact of inversions in evolution: from population genetic markers to drivers of adaptive shifts and speciation? Ann. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 39, 21–42 (2008).

Anderson, W. W. et al. Four decades of inversion polymorphism in Drosophila pseudoobscura. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 10367–10371 (1991).

Stefansson, H. et al. A common inversion under selection in Europeans. Nat. Genet. 37, 129–137 (2005).

Schaeffer, S. W. et al. Evolutionary genomics of inversions in Drosophila pseudoobscura: evidence for epistasis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 100, 8319–8324 (2003).

Pombi, M. et al. Chromosomal plasticity and evolutionary potential in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto: insights from three decades of rare paracentric inversions. BMC Evol. Biol. 8, 309 (2008).

Lowry, D. B. & Willis, J. H. A widespread chromosomal inversion polymorphism contributes to a major life-history transition, local adaptation, and reproductive isolation. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000500 (2010).

Delneri, D. et al. Engineering evolution to study speciation in yeasts. Nature 422, 68–72 (2003).

McGaugh, S. E. & Noor, M. A. F. Genomic impacts of chromosomal inversions in parapatric Drosophila species. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367, 422–429 (2012).

Noor, M. A. F., Grams, K. L., Bertucci, L. A. & Reiland, J. Chromosomal inversions and the reproductive isolation of species. PNAS 98, 12084–12088 (2001).

Rieseberg, L. H. Chromosomal rearrangements and speciation. Trends Ecol. Evol. (Amst.) 16, 351–358 (2001).

Kirkpatrick, M. & Barton, N. Chromosome inversions, local adaptation and speciation. Genetics 173, 419–434 (2006).

Navarro, A. & Barton, N. H. Accumulating postzygotic isolation genes in parapatry: a new twist on chromosomal speciation. Evolution 57, 447–459 (2003).

Faria, R. & Navarro, A. Chromosomal speciation revisited: rearranging theory with pieces of evidence. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 660–669 (2010).

Sperlich, D. & Pfriem, P. Chromosomal Polymorphim in Natural and Experimental Populations. The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila 3, (Academic Press London (1986).

White, B. J. et al. Localization of candidate regions maintaining a common polymorphic inversion (2La) in Anopheles gambiae. PLoS Genet. 3, e217 (2007).

Gordon, J. L., Byrne, K. P. & Wolfe, K. H. Mechanisms of chromosome number evolution in yeast. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002190 (2011).

Carreto, L. et al. Comparative genomics of wild type yeast strains unveils important genome diversity. BMC Genomics 9, 524 (2008).

Dunham, M. J. et al. Characteristic genome rearrangements in experimental evolution of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 16144–16149 (2002).

Adams, J., Puskas-Rozsa, S., Simlar, J. & Wilke, C. M. Adaptation and major chromosomal changes in populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 22, 13–19 (1992).

Pérez-Ortín, J. E., Querol, A., Puig, S. & Barrio, E. Molecular characterization of a chromosomal rearrangement involved in the adaptive evolution of yeast strains. Genome Res. 12, 1533–1539 (2002).

Gresham, D. et al. The repertoire and dynamics of evolutionary adaptations to controlled nutrient-limited environments in yeast. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000303 (2008).

Norman, R. A. & Prakash, S. Variation in activities of amylase allozymes associated with chromosome inversions in Drosophila pseudoobscura, D. persimilis and D. miranda. Genetics 95, 187–209 (1980).

Aminetzach, Y. T., Macpherson, J. M. & Petrov, D. A. Pesticide resistance via transposition-mediated adaptive gene truncation in Drosophila. Science 309, 764–767 (2005).

Schmidt, J. M. & Robin, C. An adaptive allelic series featuring complex gene rearrangements. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002347 (2011).

Selmecki, A. M., Dulmage, K., Cowen, L. E., Anderson, J. B. & Berman, J. Acquisition of aneuploidy provides increased fitness during the evolution of antifungal drug resistance. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000705 (2009).

Colson, I., Delneri, D. & Oliver, S. G. Effects of reciprocal chromosomal translocations on the fitness of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO Rep. 5, 392–398 (2004).

Wood, V. et al. The genome sequence of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nature 415, 871–880 (2002).

Brown, W. R. A. et al. A geographically diverse collection of Schizosaccharomyces pombe isolates shows limited phenotypic variation but extensive karyotypic diversity. G3 1, 615–626 (2011).

Rhind, N. et al. Comparative functional genomics of the fission yeasts. Science 332, 930–936 (2011).

Liti, G. et al. Population genomics of domestic and wild yeasts. Nature 458, 337–341 (2009).

Arcangioli, B. & Klar, A. J. A novel switch-activating site (SAS1) and its cognate binding factor (SAP1) required for efficient mat1 switching in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO J. 10, 3025–3032 (1991).

Molnar, M. & Kleckner, N. Examination of interchromosomal interactions in vegetatively growing diploid Schizosaccharomyces pombe cells by Cre/loxP site-specific recombination. Genetics 178, 99–112 (2008).

Coyne, J. A., Aulard, S. & Berry, A. Lack of underdominance in a naturally occurring pericentric inversion in Drosophila melanogaster and its implications for chromosome evolution. Genetics 129, 791–802 (1991).

Desai, M. M., Fisher, D. S. & Murray, A. W. The speed of evolution and maintenance of variation in asexual populations. Curr. Biol. 17, 385–394 (2007).

Murray, A. W., Schultes, N. P. & Szostak, J. W. Chromosome length controls mitotic chromosome segregation in yeast. Cell 45, 529–536 (1986).

Kegel, A. et al. Chromosome length influences replication-induced topological stress. Nature 471, 392–396 (2011).

Fraser, P. & Bickmore, W. Nuclear organization of the genome and the potential for gene regulation. Nature 447, 413–417 (2007).

Khaitovich, P. et al. Parallel patterns of evolution in the genomes and transcriptomes of humans and chimpanzees. Science 309, 1850–1854 (2005).

Janga, S. C., Collado-Vides, J. & Babu, M. M. Transcriptional regulation constrains the organization of genes on eukaryotic chromosomes. PNAS 105, 15761–15766 (2008).

Gomes, F. C. O. et al. Physiological diversity and trehalose accumulation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe strains isolated from spontaneous fermentations during the production of the artisanal Brazilian cachaça. Can. J. Microbiol. 48, 399–406 (2002).

Alexandre, H., Ansanay-Galeote, V., Dequin, S. & Blondin, B. Global gene expression during short-term ethanol stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 498, 98–103 (2001).

Chen, D. et al. Global transcriptional responses of fission yeast to environmental stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 214–229 (2003).

Lomvardas, S. et al. Interchromosomal interactions and olfactory receptor choice. Cell 126, 403–413 (2006).

Kleinjan, D. A. & Van Heyningen, V. Long-range control of gene expression: emerging mechanisms and disruption in disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76, 8–32 (2005).

Xiao, H. et al. Retrotransposon-mediated gene duplication underlies morphological variation of tomato fruit. Science 319, 1527–1530 (2008).

Meadows, L. A., Chan, Y. S., Roote, J. & Russell, S. Neighbourhood continuity is not required for correct testis gene expression in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000552 (2010).

Gordon, J. L., Byrne, K. P. & Wolfe, K. H. Additions, losses, and rearrangements on the evolutionary route from a reconstructed ancestor to the modern Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000485 (2009).

Boutanaev, A. M., Kalmykova, A. I., Shevelyov, Y. Y. & Nurminsky, D. I. Large clusters of co-expressed genes in the Drosophila genome. Nature 420, 666–669 (2002).

Roy, P. J., Stuart, J. M., Lund, J. & Kim, S. K. Chromosomal clustering of muscle-expressed genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 418, 975–979 (2002).

Spellman, P. T. & Rubin, G. M. Evidence for large domains of similarly expressed genes in the Drosophila genome. J. Biol. 1, 5 (2002).

Díaz-Castillo, C., Xia, X.-Q. & Ranz, J. M. Evaluation of the role of functional constraints on the integrity of an ultraconserved region in the genus Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002475 (2012).

Moreno, S., Klar, A. & Nurse, P. inMethods in Enzymology Vol. 194, ed. Christine Guthrie G.R.F 795–823Academic Press (1991).

Kelly, M., Burke, J., Smith, M., Klar, A. & Beach, D. Four mating-type genes control sexual differentiation in the fission yeast. EMBO J. 7, 1537–1547 (1988).

Ferreira, M. G. & Cooper, J. P. The fission yeast Taz1 protein protects chromosomes from Ku-dependent end-to-end fusions. Mol. Cell 7, 55–63 (2001).

Rozas, J. & Rozas, R. DnaSP version 3: an integrated program for molecular population genetics and molecular evolution analysis. Bioinformatics 15, 174–175 (1999).

Gingolg, E. B. Experiments in Molecular Biology 247-–253Humana Press (1986).

Bähler, J. et al. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR‐based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14, 943–951 (1998).

Acknowledgements

This interdisciplinary work reflects the scientific environment of the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (IGC). We thank M. Molnar and N. Kleckner (Harvard University) for generously providing the Cre-loxP strains, the Portuguese Yeast Culture Collection and CA Rosa (UF Minas Gerais) for the natural isolate strains, B. Arcangioli (I Pasteur) for advices on disruption of switchable mating-type, J. Mata (University of Cambridge) for technical assistance with RNA purification and gene expression analysis, P. Duarte and S. Rosa (IGC) for technical assistance, M. Carneiro (IGC) for assistance with qRT-PCR, R, Gardner and T. Lopes (IGC) for technical support with flow cytometry. We thank António Coutinho and Henrique Teotónio (IGC) for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by the Portuguese Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) PTDC/BIA-EVF/114460/2009. A.T.A. and L.P. were funded by FCT PhD and Postdoctoral fellowships, respectively. MGF is a HHMI International Early Career Scientist.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed the experiments, analysed data, discussed the results and wrote the manuscript. A.T.A. performed most experiments and L.P. performed antagonistic pleiotropy experiments. I.G. advised and gave support to all experiments. M.G.F. supervised all the work performed.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S11, Supplementary Tables S1-S4, Supplementary Reference and Supplementary Note (PDF 2142 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Teresa Avelar, A., Perfeito, L., Gordo, I. et al. Genome architecture is a selectable trait that can be maintained by antagonistic pleiotropy. Nat Commun 4, 2235 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3235

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3235

This article is cited by

-

Heterogeneous rates of genome rearrangement contributed to the disparity of species richness in Ascomycota

BMC Genomics (2018)

-

Power law fitness landscapes and their ability to predict fitness

Heredity (2018)

-

Assembly of Schizosaccharomyces cryophilus chromosomes and their comparative genomic analyses revealed principles of genome evolution of the haploid fission yeasts

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Transient structural variations have strong effects on quantitative traits and reproductive isolation in fission yeast

Nature Communications (2017)

-

Evolutionary mechanisms of runaway chromosome number change in Agrodiaetus butterflies

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.