Abstract

Antiferroelectrics are essential ingredients for the widely applied piezoelectric and ferroelectric materials: the most common ferroelectric, lead zirconate titanate is an alloy of the ferroelectric lead titanate and the antiferroelectric lead zirconate. Antiferroelectrics themselves are useful in large digital displacement transducers and energy-storage capacitors. Despite their technological importance, the reason why materials become antiferroelectric has remained allusive since their first discovery. Here we report the results of a study on the lattice dynamics of the antiferroelectric lead zirconate using inelastic and diffuse X-ray scattering techniques and the Brillouin light scattering. The analysis of the results reveals that the antiferroelectric state is a ‘missed’ incommensurate phase, and that the paraelectric to antiferroelectric phase transition is driven by the softening of a single lattice mode via flexoelectric coupling. These findings resolve the mystery of the origin of antiferroelectricity in lead zirconate and suggest an approach to the treatment of complex phase transitions in ferroics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The notion of antiferroelectricity dates back to the early 1950s. At that time, Kittel1 proposed a theory of antiparallel ionic displacements in dielectrics using the antiferromagnetism scheme. In parallel, Sawaguchi et al.2,3 assigned the perovskite lead zirconate, PbZrO3 (PZ), as antiferroelectric because of its dielectric behaviour. Thereafter, materials that exhibited a structural phase transition between two non-polar phases with a strong dielectric anomaly at the high temperature side of the transition were named antiferroelectrics, PZ remaining the prototype for this large group of materials.

In contrast to antiferromagnetism, the description of antiferroelectricity requires the introduction of two instabilities at close temperatures (nearly simultaneous softening of two lattice modes). In the context of Landau theory, this is quite an improbable event. In real materials, PZ being a classical example, the situation can be even more unusual. Here, in addition to the softening of the lattice mode that is responsible for the critical divergence of the dielectric permittivity, at least two other order parameters corresponding to two different points in the Brillouin zone are needed to describe the transition-driven structural changes. Thus, it looks as if coincidentally, the material exhibits at once three relevant, strongly softening lattice modes, one responsible for the dielectric anomaly and two for the transition. Despite systematic experimental and theoretical studies of PZ and the discovery of some 100 other antiferroelectrics4 over the last 60 years5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, the physical reason for this phenomenon remains unknown.

In this paper, we revisit antiferroelectricity in PZ by first-time application of the inelastic X-ray scattering (IXS) technique, diffuse X-ray scattering and Brillouin light scattering to study its pre-transitional lattice dynamics. Our experimental results show that the transition in PZ is driven by the softening of a single lattice mode, which is actually the ferroelectric soft mode in perovskites, whereas the antiferroelectric state in PZ can be viewed as a ‘missed’ incommensurate phase. An essential feature of our scenario for the structural transformations in PZ is the strain-gradient/polarization (flexoelectric) coupling14,15,16,17. It is this coupling that ‘transforms’ the ferroelectric softening into an antiferroelectric phase transition.

Results

Modes controlling antiferroelectricity in lead zirconate

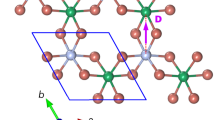

At high temperatures, PZ has the ideal cubic perovskite structure shown in Fig. 1a.

(a) Unit cell of lead zirconate in the cubic phase. (b) The Γ-point polar mode controlling the dielectric anomaly (shown schematically for one of the possible orientations of its dipole moment). (c) Lead displacements in the Σ mode. (d) Oxygen-octahedron rotations in the R mode. Directions of the cubic crystallographic axes in the ab plane are shown as dotted lines. In c and d, the projections of the orthorhombic unit cell onto the ab plane are shown.

After cooling through a first-order phase transition at TA~ 500 K, the structure changes from cubic m m to orthorhombic mmm with an eightfold increase of the number of atoms per unit cell2. In spite of both phases being centrosymmetric, the phase transition is accompanied by a strong Curie–Weiss type anomaly of the dielectric constant (up to 6,000 (ref. 8)) above the transition. Because of this behaviour, PZ is classified as an antiferroelectric. In contrast, in ferroelectrics, a similar dielectric anomaly is imperatively combined with the transition to a non-centrosymmetric low-temperature phase (for example, BaTiO3).

m to orthorhombic mmm with an eightfold increase of the number of atoms per unit cell2. In spite of both phases being centrosymmetric, the phase transition is accompanied by a strong Curie–Weiss type anomaly of the dielectric constant (up to 6,000 (ref. 8)) above the transition. Because of this behaviour, PZ is classified as an antiferroelectric. In contrast, in ferroelectrics, a similar dielectric anomaly is imperatively combined with the transition to a non-centrosymmetric low-temperature phase (for example, BaTiO3).

Antiferroelectric behaviour of a crystal can be rationalized in terms of a simple two-instability Landau-type theory18,19,20. The dielectric anomaly is attributed to the softening of a transverse optic polar mode at the Γ point of Brillouin zone. The Curie temperature T0 for this softening is close to but lower than the transition temperature TA. Such mode softening is identical to that in ferroelectrics. However, in contrast to ferroelectrics, in antiferroelectrics, this mode softening is interrupted at T=TA by a repulsive interaction between the polarization and the structural order parameter appearing at the transition. If this coupling is strong enough, the frequency of the ferroelectric soft mode increases on cooling below TA. This entails a decrease in the dielectric constant with lowering temperature below the transition. Such evolution of the dielectric constant with temperature is typical for antiferroelectrics.

This scenario can be modelled with the following free energy expansion in terms of the polarization, P, and the structural order parameter, ξ,

where the coefficient δP>0 controls the repulsive biquadratic coupling between the polarization and the structural order parameter. The transition at T=TA is described by the contribution to the free energy FA(ξ), implying softening of a lattice mode associated with the order parameter ξ. The corresponding critical temperature,  , should be equal to TA or slightly lower than TA. Using the equation of state for polarization ∂F/∂P=E (E is the electric field), for the high-temperature phase (with ξ=0), equation (1) yields the Curie–Weiss law χ

, should be equal to TA or slightly lower than TA. Using the equation of state for polarization ∂F/∂P=E (E is the electric field), for the high-temperature phase (with ξ=0), equation (1) yields the Curie–Weiss law χ  1/(T–T0) for the dielectric susceptibility defined as χ=dP/dE. Similarly, for the low-temperature phase where the order parameter of the transition, ξ, acquires a spontaneous value of ξ0, the susceptibility can be found in the form:

1/(T–T0) for the dielectric susceptibility defined as χ=dP/dE. Similarly, for the low-temperature phase where the order parameter of the transition, ξ, acquires a spontaneous value of ξ0, the susceptibility can be found in the form:

Equation (2) corresponds to the aniferroelectric-type anomaly if  increases on cooling. This is possible if the increase of ξ0 with lowering temperature dominates the behaviour of this term. Such a condition can be assured by a large enough coupling constant δP. (See Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Note 1 for more information about the description of antiferroelectricity in terms of expansion (1).)

increases on cooling. This is possible if the increase of ξ0 with lowering temperature dominates the behaviour of this term. Such a condition can be assured by a large enough coupling constant δP. (See Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Note 1 for more information about the description of antiferroelectricity in terms of expansion (1).)

In the approach discussed above, the appearance of antiferroelectricity requires the presence of at least two soft lattice modes with close instability temperatures. In PZ, the situation is even more complicated: the structural changes in the material cannot be described by one order parameter. For a given orientational domain state, the changes observed can be presented as a combination of displacements in two lattice modes21: one corresponding to the Σ point (the wave vector  ; a is the cubic lattice constant) on the Σ direction in Brillouin zone and the other corresponding to the R point (

; a is the cubic lattice constant) on the Σ direction in Brillouin zone and the other corresponding to the R point ( ). Hereafter, we will refer to these modes as Σ and R modes, respectively. The distortions associated with the Σ point are mainly related to displacements of lead ions, whereas the R mode is related to antiphase rotations of the oxygen octahedra above the crystallographic axes of the cubic phase. The displacement patterns corresponding to the Σ and R modes are schematically shown in Fig. 1c,d. For other orientational domains, the modulations of the ionic displacements correspond to the other wave vectors from the star of the wave vector kΣ.

). Hereafter, we will refer to these modes as Σ and R modes, respectively. The distortions associated with the Σ point are mainly related to displacements of lead ions, whereas the R mode is related to antiphase rotations of the oxygen octahedra above the crystallographic axes of the cubic phase. The displacement patterns corresponding to the Σ and R modes are schematically shown in Fig. 1c,d. For other orientational domains, the modulations of the ionic displacements correspond to the other wave vectors from the star of the wave vector kΣ.

Therefore, apparently three lattice modes control the behaviour of PZ, schematically shown in Fig. 1b–d: the Σ and R modes govern the structural changes at the transition, whereas the Γ point mode is responsible for the dielectric anomaly. The fact that all three modes soften at critical temperatures very close to one another would be an unusual coincidence. Is there an intrinsic mechanism that triggers this behaviour? We applied inelastic and diffuse X-ray scattering techniques and Brillouin light scattering to answer this question.

Lattice dynamics of PZ from X-ray and Brillouin scattering

For information on the lattice vibration softening in the high-temperature phase, we examined the Σ, Γ and R points of the Brillouin zone, using IXS technique. First, we addressed the low-frequency spectra of lattice vibrations for wave vectors close to the Σ direction of the Brillouin zone, containing the Σ and Γ points. We found the TA branch with polarization along [ ,1,0] to be of anomalously low frequency (energy) and heavily damped for all the wave vectors in the Σ direction (Fig. 2a). Remarkably, such a low energy of the branch in the interior of the Brillouin zone coexists with the ‘normal value’ of the corresponding sound velocity obtained from our Brillouin light scattering data, shown as the dashed line in Fig. 2a. For other wave vectors and polarizations, the situation is not striking—the phonons are weakly damped and have ‘normally large’ frequencies (Supplementary Figs S2 and S3, Supplementary Note 2). Apparently, the spectrum of the in-plane polarized TA mode is strongly anisotropic: once the wave vector deviates from the Σ direction, its frequency increases steeply, and a ‘valley’ is seen along the Σ direction when the mode frequency is plotted against the wave vector in the (001) plane (Fig. 2b).

,1,0] to be of anomalously low frequency (energy) and heavily damped for all the wave vectors in the Σ direction (Fig. 2a). Remarkably, such a low energy of the branch in the interior of the Brillouin zone coexists with the ‘normal value’ of the corresponding sound velocity obtained from our Brillouin light scattering data, shown as the dashed line in Fig. 2a. For other wave vectors and polarizations, the situation is not striking—the phonons are weakly damped and have ‘normally large’ frequencies (Supplementary Figs S2 and S3, Supplementary Note 2). Apparently, the spectrum of the in-plane polarized TA mode is strongly anisotropic: once the wave vector deviates from the Σ direction, its frequency increases steeply, and a ‘valley’ is seen along the Σ direction when the mode frequency is plotted against the wave vector in the (001) plane (Fig. 2b).

(a) Dispersion curves for the phonons, propagating in Σ direction (q=(q,q,0)) of the reciprocal space and polarized in (0,0,1) plane: blue circles −780 K, red squares −550 K (X-ray scattering data). Errorbars correspond to 95% confidence interval. The dashed line indicates the slope of the dispersion curves in the vicinity of the Γ point, extracted from Brillouin light scattering data (Supplementary Fig. S4, Supplementary Note 3). Comparison of the X-ray and light scattering data suggests that the phonon energy is anomalously low in the interior of the Brillouin zone. (b) Dispersion surface for the lowest TA phonons, propagating and polarized in the (0,0,1) lattice plane at 780 K. The wave vectors are measured in the units of the reciprocal cubic lattice constant a*=2π/a.

Along the valley, the orientation of the ionic displacements in the anomalous acoustic mode coincides with that of the lead ions in the low-temperature phase. Thus, the freezing of this mode with the wave vector kΣ might be considered as the origin of the phase transformation at T=TA. However, no minimum was found at this point on the dispersion curve. The frequency of the transverse mode at the bottom of the valley decreases slightly on approaching TA, however, no traces of criticality are seen (see the data points in Fig. 2a).

Another remarkable feature of the low-frequency spectra is a central peak for wave vectors along the Σ direction (Supplementary Fig. S2, Supplementary Notes 2 and 4). It is polarized identically to the anomalous transverse acoustic mode. Its integral intensity increases appreciably upon cooling towards the transition temperature (see Fig. 3). This peak corresponds to the Γ point softening of a relaxational polar lattice excitation, which was earlier identified in PZ by Ostapchuk et al.21 by far infrared and dielectric spectroscopy. Similar non-phonon soft modes were also identified in other materials22,23.

The dependence corresponds to the the momentum transfer Q=(2.15,2.85,0) (reduced scattered wave vector q=(0.15,−0.15,0)). Errorbars correspond to 95% confidence interval. Fit to equation (3) is shown as solid line. The wave vectors are measured in the units of the reciprocal cubic lattice constant a*=2π/a.

The temperature dependence of the central peak intensity observed in our experiments is consistent with the prediction of mean-field theory24 for the critical dependence of the integral intensity:

where q is the scattered wave vector, g is a constant and T0=485 K is taken from the dielectric data3 (Fig. 3). Thus, our data attest to the softening of a relaxational ferroelectric polar mode at the Γ point when approaching the Curie temperature, T0.

Our analysis of the modes at the R point did not reveal any softening relevant to the phase transition in question (Supplementary Figs S5 and S6, Supplementary Note 5).

Antiferroelectricity in PZ as a missed incommensurate phase

Unexpectedly, our data suggest that there is no critical softening in the lattice except for the Γ relaxational mode. Therefore, the next objective becomes the understanding of the relationship between this critical process and other observed phenomena, namely, (1) the anomalous dispersion and non-critical softening of the TA branch and (2) the development of the long-range structural order corresponding to the Σ and R points.

To answer the first question, we compare the spectrum shown in Fig. 2a with the classical phonon spectra for cubic ferroelectric perovskites PbTiO3 (ref. 25) and KTaO3 (ref. 14). The frequency of the transverse acoustic mode in these crystals is strongly suppressed with increasing wave vector due to the interaction of this mode with the soft optic mode via the flexoelectric coupling. In continuum theory, this coupling is controlled by the flexocoupling tensor fijkl in the free-energy expansion in terms of polarization vector Pi and strain tensor uij26:

where α=A(T–T0). Hereafter, the Einstein summation convention is adopted. The flexoelectric coupling induces a repulsion between the optic and the acoustic modes. Via this repulsion, the critical softening of the optic mode leads to a suppression of the frequency of the acoustic mode. The similarity between the spectrum of the anomalous mode in PZ and those in cubic ferroelectric perovskites suggests that the low energy and weak dispersion of the anomalous mode is conditioned upon its flexoelectric coupling with the soft polar optic mode. Therefore, the critical softening of the Γ-point mode is responsible for both the dielectric anomaly at the high-temperature side of the transition and for some reduction in the TA mode frequency on approaching the transition (see Fig. 2a).

Determining the decisive role of flexoelectricity in the phase transformation of PZ is more challenging than for PbTiO3 and KTaO3. The ferroelectric soft mode in these crystals is a phonon-type excitation, and its temperature evolution can be readily traced experimentally14,25. By contrast in PZ, as was mentioned above, the lattice mode related to the dielectric anomaly manifests itself in dynamical response as a relaxation excitation rather than as a phonon. The critical central peak observed in our measurements (Fig. 3) is a trace of this excitation. However, the accuracy of our IXS experiment does not suffice to evaluate the spectral parameters of this soft mode, needed for further justification of the ‘flexoelectric scenario’. At the same time, our analysis (see Supplementary Note 6) shows that the flexoelectric coupling should result in a specific correlation pattern of thermal atomic displacements that can be tested with X-ray diffuse scattering. We carried out X-ray diffuse scattering measurements and fit the experimental data to a lattice dynamics model incorporating the flexoelectric coupling27,28. Figure 4 shows the experimental data and the fit for six two-dimensional cross-sections of the diffuse scattering intensity maps around the (0,0, ) and (0,1,

) and (0,1, ) reciprocal lattice points.

) reciprocal lattice points.

A very good qualitative agreement is provided with the model that takes into account the flexoelectric coupling, whereas without this coupling, the specific features of the DS maps cannot be reproduced. Thus, our analysis of the data on inelastic and diffuse X-ray scattering and Brillouin scattering identifies unambiguously the softening of the ‘ferroelectric’ optical mode as the driving force (via the flexoelectric coupling) for the specific form of the anomalous transverse acoustic mode.

It was pointed out in the classical paper by Axe et al.14 that the flexoelectric coupling can drive the phonon frequency to zero at a certain wave vector inside the Brillouin zone, leading to the formation of an incommensurate phase. For the anomalous TA mode polarized along the [ ,1,0] direction, it is the component f11–f12 of the flexocoupling tensor that controls the effect (hereafter, the Voigt notations are used for all fourth-rank tensors). Following the analysis from Axe et al.14, one can show that an incommensurate phase is expected when the factor

,1,0] direction, it is the component f11–f12 of the flexocoupling tensor that controls the effect (hereafter, the Voigt notations are used for all fourth-rank tensors). Following the analysis from Axe et al.14, one can show that an incommensurate phase is expected when the factor  becomes larger than one, where c′s and g′s are the components of the elastic stiffness and correlation energy tensors, respectively. Order-of-magnitude estimates suggest that perovskite ferroelectrics are not far from an incommensurate instability (Supplementary Note 7). Indeed, incommensurate states were observed in these materials, specifically in modified lead zirconate29,30. As for pure PZ, based on the parameters used for the simulation of diffuse X-ray scattering (Fig. 4), one can roughly estimate the parameter Θ as 0.9, which is quite close to its critical value (see Supplementary Note 6). Thus, our data on the inelastic diffuse X-ray scattering suggest that, in PZ, on approaching the phase transition, the crystal is ready to go to an incommensurate phase but a low-temperature antiferroelectric commensurate state forms instead. Namely, an incommensurate phase is avoided on the account of the appearance of an antiferroelectric phase.

becomes larger than one, where c′s and g′s are the components of the elastic stiffness and correlation energy tensors, respectively. Order-of-magnitude estimates suggest that perovskite ferroelectrics are not far from an incommensurate instability (Supplementary Note 7). Indeed, incommensurate states were observed in these materials, specifically in modified lead zirconate29,30. As for pure PZ, based on the parameters used for the simulation of diffuse X-ray scattering (Fig. 4), one can roughly estimate the parameter Θ as 0.9, which is quite close to its critical value (see Supplementary Note 6). Thus, our data on the inelastic diffuse X-ray scattering suggest that, in PZ, on approaching the phase transition, the crystal is ready to go to an incommensurate phase but a low-temperature antiferroelectric commensurate state forms instead. Namely, an incommensurate phase is avoided on the account of the appearance of an antiferroelectric phase.

To introduce this scenario, we start with the description of the possibility of formation of an incommensurate phase with a wave vector parallel to the [1,1,0] direction, having an absolute value k0. We consider an order parameter, Ak, corresponding to the low-lying acoustic mode for a wave vector k parallel to this direction. Atomic displacements in the corresponding modulated structure are proportional to the real part of the complex wave:

For any k, one can always write the following contribution to the free energy corresponding to this order parameter24:

where αk(T) decreases with falling temperature and γk>0 to provide the global stability of the system. A second-order phase transition to an incommensurate phase with a structural modulation corresponding to wave vector k0 occurs at T=Ti if (i)  >0, (ii) αk(T) has a minimum at k=k0 and (iii)

>0, (ii) αk(T) has a minimum at k=k0 and (iii)  (Ti)=0. If

(Ti)=0. If  <0, a first-order phase transition will take place at a temperature higher than Ti.

<0, a first-order phase transition will take place at a temperature higher than Ti.

This framework also enables a competing scenario with the formation of a commensurate modulated structure corresponding to the wave vector  . The point is that, in view of a spatially oscillating form of the order parameter given by equation (5), for a general point of the Brillouin zone, only its absolute value (where the oscillations are eliminated) can enter the expression for the free energy (cf equation (6)). Meanwhile, for the points corresponding to 1/4 of a reciprocal lattice vector, taking the 4th power of the order parameter eliminates these oscillations as well. This way the so-called Umklapp invariant (Ak)4+(A−k)4 enters the Landau expansion24. Thus, the energy describing a transition with the wave vector kΣ can be presented in the form:

. The point is that, in view of a spatially oscillating form of the order parameter given by equation (5), for a general point of the Brillouin zone, only its absolute value (where the oscillations are eliminated) can enter the expression for the free energy (cf equation (6)). Meanwhile, for the points corresponding to 1/4 of a reciprocal lattice vector, taking the 4th power of the order parameter eliminates these oscillations as well. This way the so-called Umklapp invariant (Ak)4+(A−k)4 enters the Landau expansion24. Thus, the energy describing a transition with the wave vector kΣ can be presented in the form:

where the third term on the right-hand side is conditioned by the Umklapp invariant. Here, α, βΣ and γ are respectively αk(T), βk, and γk taken at k=kΣ, and the amplitude of the complex order parameter is expressed in terms of its modulus ρ and phase φ:

The ground state described by equation (7) occurs at the values of the order-parameter phase φ, satisfying the condition ∂FΣ/∂φ=0. For βU>0, it corresponds to φ=π/4, 3π/4, 5π/4, 7π/4, whereas, for βU<0, it corresponds to φ=0, π/2, π, 3π/2. Inserting these values of φ into equation (7), one finds the free energy in terms of the modulus of the order parameter:

where β=βΣ−βU for βU>0 and β=βΣ+βU for βU<0. Note that β<βΣ irrespective of the sign of βU.

Let us see under which condition the free energy given by equation (9) can describe the modulated structure with k=kΣ observed in PZ (lead displacements in this structure are schematically shown in Fig. 1c). First of all, if β>0, this free energy cannot describe such a structure at all. In this case, due to β>0, a second-order phase transition to the low temperature phase might occur, provided that αk(T) has a minimum at k=kΣ. However, the latter is not the case because the anomalous transverse mode does not have minimum at k=kΣ as seen from Fig. 2a. If β<0, the free energy given by equation (9) does describe a first-order phase transition to a modulated structure with k=kΣ. Remarkably, in this case, there is no need for a minimum of αk(T) at k=kΣ. In contrast to the case of the second-order phase transition, the priority of the commensurate modulation is not ensured by the corresponding minimum on the dispersion curve of the relevant lattice excitation but rather by the fact that the coefficient for anharmonic term, β (controlling the transition at k=kΣ) is always smaller than βΣ, which controls possible transitions at the neighbouring wave vectors. Note that the energy of the anomalous acoustic mode at these wave vectors at the transition temperature, ≈1.5 meV, is comparable to that of the ferroelectric soft mode in BaTiO3 just above the first-order phase transition, ≈1.8 meV (evaluated from the dielectric data). Thus, we can consider the energy of the anomalous acoustic mode to be low enough to trigger a first-order phase transition.

Thus, the weak softening of the anomalous transverse mode with lowering temperature is compatible with the formation of a modulated structure with k=kΣ via a first-order phase transition. The characteristic pattern of the lead displacements in PZ shown in Fig. 1c can be readily reproduced by our framework under the condition that βU>0 (Supplementary Note 8).

This scenario can be viewed as an incommensurate phase transition going directly to the lock-in phase skipping the incommensurate phase, with the flexoelectric coupling being the driving force of the effect. This recalls a recent study by Borisevich et al.31 on the bridging phase between a ferroelectric and antiferroelectric state in modified BiFeO3, where this phase was treated as a manifestation of flexoelectricity. The framework presented above may also be applied to this system.

Now that the order parameter of the transition is identified, we can specify the repulsive coupling that suppresses the Γ-point ‘ferroelectric’ instability at the transition. The free-energy terms corresponding to this coupling in the orientational domain state specified above read  . Using these terms in equation (1) and following the explanations above, we conclude that the antiferroelectric-type dielectric anomaly will take place if the coupling constants δP1 and δP3 are positive and large enough. Such phenomenological scenario is consistent with the first-principles results by Waghmare and Rabe11, which suggest a competition between the Σ and Γ modes.

. Using these terms in equation (1) and following the explanations above, we conclude that the antiferroelectric-type dielectric anomaly will take place if the coupling constants δP1 and δP3 are positive and large enough. Such phenomenological scenario is consistent with the first-principles results by Waghmare and Rabe11, which suggest a competition between the Σ and Γ modes.

Finally, we address the R-point-related oxygen-octahedron rotations (Fig. 1d). This can be incorporated into our model via the Holakovsky ‘trigger’ mechanism32. This mechanism was recently identified with ab initio calculations in perovskite ferroelectrics33. Following Holakovsky32, we introduce an attractive biquadratic coupling between the order parameter of the transition ξk and another order parameter—a real pseudovector Φ describing the oxygen-octahedron rotations in question. For the orientational domain state corresponding to the wave vector k=kΣ, the free energy taking into account the oxygen-octahedron rotation and its coupling with the order parameter of the transition reads:

where FΣ is a function of the order parameter only. If at least one of the coupling constants and is negative, the appearance of the spontaneous order parameter of the transition, ρ0, may trigger that of the order parameter Φ. This happens if at the transition point either  or

or  is negative. In the case of PZ, in the considered orientational domain state, Φ1=Φ2≠0, whereas Φ3=0 (ref. 5). The considered phenomenological framework describes this situation if <0 and at the transition

is negative. In the case of PZ, in the considered orientational domain state, Φ1=Φ2≠0, whereas Φ3=0 (ref. 5). The considered phenomenological framework describes this situation if <0 and at the transition  Thus, in our scenario, the oxygen-octahedron rotations in PZ are induced by the anti-polar lead displacements via an attractive biquadratic mode coupling. Such a phenomenological scenario is consistent with the conclusion drawn by Waghmare and Rabe11 from their first-principles calculations concerning the cooperation between the Σ and R modes. At the same time, our phenomenological model differs from the effective hamiltonian, which is partially based on first-principles calculations, applied by Leung et al.34 to describe the mmm phase in PbZr0.95Ti0.05O3. Specifically, in their work, biquadratic couplings with non-zone-boundary, non-zone-centre displacements are not explicitly treated, although such couplings (with the mode at

Thus, in our scenario, the oxygen-octahedron rotations in PZ are induced by the anti-polar lead displacements via an attractive biquadratic mode coupling. Such a phenomenological scenario is consistent with the conclusion drawn by Waghmare and Rabe11 from their first-principles calculations concerning the cooperation between the Σ and R modes. At the same time, our phenomenological model differs from the effective hamiltonian, which is partially based on first-principles calculations, applied by Leung et al.34 to describe the mmm phase in PbZr0.95Ti0.05O3. Specifically, in their work, biquadratic couplings with non-zone-boundary, non-zone-centre displacements are not explicitly treated, although such couplings (with the mode at  are the principle ingredients of our model.

are the principle ingredients of our model.

Discussion

We addressed the lattice dynamics of prototypical antiferroelectric PbZrO3, using inelastic and diffuse X-ray scattering and Brillouin light scattering. Based on our experimental data, we showed that the driving force for antiferroelectricity is a single (ferroelectric) instability. Through flexoelectric coupling, it drives the system to a state, which is virtually unstable against incommensurate modulations. However, the Umklapp interaction allows the system to go directly to the commensurate lock-in phase, leaving the incommensurate phase as a ‘missed’ opportunity. By this mechanism, the ferroelectric softening is transformed into an antiferroelectric transition. The remaining key parts of the whole scenario are the repulsive and attractive biquadratic couplings, which suppress the appearance of the spontaneous polarization and induce the anti-phase octahedral rotations in the low-temperature phase. Such couplings are readily allowed by the crystalline symmetry of perovskite ferroelectrics and antiferroelectrics, and are likely therefore to control or at least have a dominant role in similar phenomena (for example, antiferroelectricity in BiFeO3 derivatives (Borisevich et al.31 and Goian et al.35).

Methods

Samples

Lead zirconate crystals were grown from high-temperature solutions (flux growth method) by means of spontaneous crystallization. The Pb3O4–B2O3 mixture (soaking at 1,350 K) was used as a solvent. The temperature of the melt was reduced at a rate 3.5 K h−1 down to 1,120 K. The remaining melt was decanted, and as-grown crystals attached to the crucible walls were cooled to room temperature at a rate of 10 K h−1. In the final step, the as-grown crystals were etched in dilute acetic acid to remove residues of the solidified flux.

The crystal studied exhibited a narrow intermediate phase on heating with a lattice distortion corresponding to the M point ( ) of the Brillouin zone, which had been earlier reported by Fujishita and Hoshino7. Tentatively, it may correspond to the phase reported by Roleder et al.6 The samples for the X-ray scattering experiments were taken from the same batch, whereas the Brillouin measurements were carried out with separately grown crystals.

) of the Brillouin zone, which had been earlier reported by Fujishita and Hoshino7. Tentatively, it may correspond to the phase reported by Roleder et al.6 The samples for the X-ray scattering experiments were taken from the same batch, whereas the Brillouin measurements were carried out with separately grown crystals.

IXS measurements

The lattice dynamics of the PbZrO3 crystal was studied using the IXS technique. The experiment was done at BL35XU high-resolution IXS beamline of the SPring-8 synchrotron radiation source. A Si(11 11 11) monochromator (E=21.748 keV) was used, giving 1.5 meV full width at half maximum resolution. X-rays scattered by the sample were analysed by 12 analysers, providing information for 12 values of the scattering vector. Experimentally measured spectra were fitted using the least-square technique to a sum of phonon resonances approximated by the damped harmonic oscillator lineshape convoluted with experimental resolution and Lorentzian-shaped quasi-elastic peak at zero transmitted energy.

Diffuse scattering measurements

Measurements of diffuse scattering were carried out using general purpose KUMA6 diffractometer at BM01A Swiss-Norwegian Beamline of ESRF. A sagittally focusing Si(1 1 1) monochromator was used, and wavelength λ=0.99 Å was selected and calibrated with a NIST LaB6 standard. Diffraction patterns were recorded using a MAR345 detector. All the measurements were performed with a small single crystal having the shape of a rectangular parallelepipedon of about 20 × 20 × 500 μm3. The sample was mounted at the goniometer and heated by a flow of hot nitrogen. The temperature was regulated with an ESRF heat blower with a stability of 0.5 K. Three-dimensional reconstructions of the scattering intensity in reciprocal space and two-dimensional cross-sections of these reconstructions were performed using Volvox program.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Tagantsev, A. K. et al. The origin of antiferroelectricity in PbZrO3. Nat. Commun. 4:2229 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3229 (2013).

References

Kittel, C. Theory of antiferroelectric crystals. Phys. Rev. 82, 729–732 (1951).

Maniwa, H., Sawaguchi, E. & Hoshino, S. Antiferroelectric structure of lead zirconate. Phys. Rev. 83, 1078–1078 (1951).

Shirane, G., Sawaguchi, E. & Takagi, Y. Dielectric properties of lead zirconate. Phys. Rev. 84, 476–481 (1951).

Isupov, V. A. Ferroelectric and antiferroelectric perovskites PbB′0.5B0.5O3 . Ferroelectrics 289, 131–195 (2003).

Whatmore, R. W. & Glazer, A. M. Structural phase transitions in lead zirconate. J. of Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 12, 1505–1519 (1979).

Roleder, K. et al. The 1st evidence of 2 phase-transitions in PbZrO3 crystals derived from simultaneous raman and dielectric measurements. Ferroelectrics 80, 809–812 (1988).

Fujishita, H. & Hoshino, S. A study of structural phase transitions in antiferroelectric PbZrO3 by neutron diffraction. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 53, 226–234 (1984).

Viehland, D. Transmission electron microscopy study of high-Zr-content Lead Zirconate Titanate. Phys. Rev. B 52, 778–791 (1995).

Tan, X. L., Ma, C., Frederick, J., Beckman, S. & Webber, K. G. The antiferroelectric ferroelectric phase transition in lead-containing and lead-free perovskite ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 94, 4091–4107 (2011).

Singh, D. J. Structure and energetics of antiferroelectric PbZrO3 . Phys. Rev. B 52, 12559–12563 (1995).

Waghmare, U. V. & Rabe, K. M. Lattice instabilities, anharmonicity and phase transitions in PbZrO3 from first principles. Ferroelectrics 194, 135–147 (1997).

Ghosez, P., Cockayne, E., Waghmare, U. V. & Rabe, K. M. Lattice dynamics of BaTiO3, PbTiO3, and PbZrO3: a comparative first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 60, 836–843 (1999).

Cockayne, E. & Rabe, K. M. Pressure dependence of instabilities in perovskite PbZrO3 . J. Phys. Chem. Solids 61, 305–308 (2000).

Axe, J. D., Harada, J. & Shirane, G. Anomalous acoustic dispersion in centrosymmetric crystals with soft optic phonons. Phys. Rev. B 1, 1227–1234 (1970).

Kogan, S. h. M. Piezoelectric effect during inhomogeneous deformation and acoustic scttering of carriers in crystals. Sov. Phys. Solid State 5, 2069–2070 (1964).

Tagantsev, A. K. Piezoelectricity and flexoelectricity in crystalline dielectrics. Phys. Rev. B 34, 5883–5889 (1986).

Cross, L. E. Flexoelectric effects: charge separation in insulating solids subjected to elastic strain gradients. J. Mat. Sci. 41, 53–63 (2006).

Cross, L. E. A thermodynamic treatment of ferroelectricity and antiferroelectricity in pseudo-cubic dielectrics. Philos. Mag. 1, 76–92 (1956).

Okada, K. Phenomenological theory of antiferroelectric transition. i. second-order transition. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 27, 420–428 (1969).

Balashova, E. V. & Tagantsev, A. K. Polarization response of crystals with structural and ferroelectric instabilities. Phys. Rev. B 48, 9979–9986 (1993).

Ostapchuk, T. et al. Polar phonons and central mode in antiferroelectric PbZrO3 ceramics. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 13, 2677–2689 (2001).

Hlinka, J. et al. Coexistence of the phonon and relaxation soft modes in the terahertz dielectric response of tetragonal BaTiO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 167402 (2008).

Buixaderas, E., Kamba, S. & Petzelt, J. Lattice dynamics and central-mode phenomena in the dielectric response of ferroelectrics and related materials. Ferroelectrics 308, 131–192 (2004).

Bruce, A. D. & Cowley, R. A. Structural phase transitions Taylor and Francis: London, (1981).

Shirane, G., Axe, J. D., Harada, J. & Remeika, J. P. Soft ferroelectric modes in lead titanate. Phys. Rev. B 2, 155–159 (1970).

Indenbom, V. L., Loginov, E. B. & Osipov, M. A. Flexoelectric effect and the structure of crystals. Kristalografija 26, 1157–1162 (1981).

Vaks, V. G. Introduction to the Microscopic Theory of Ferroelectrics Nauka: Moscow, (1973).

Farhi, E. et al. Low energy phonon spectrum and its parameterization in pure KTaO3 below 80 K. Eur. Phys. J. B 15, 615–623 (2000).

He, H. & Tan, X. A. Electric-field-induced transformation of incommensurate modulations in antiferroelectric Pb0.99Nb0.02[(Zr1−xSnx) 1−yTiy]0.98O3 structural phase transitions. Phys. Rev. B 72, 024102 (2005).

MacLaren, I., Villaurrutia, R. & Pelaiz-Barranco, A. Domain structures and nanostructures in incommensurate antiferroelectric PbxLa1−xZr0.9Ti0.1O3 . J. App. Phys. 108, 034109 (2010).

Borisevich, A. Y. et al. Atomic-scale evolution of modulated phases at the ferroelectric-antiferroelectric morphotropic phase boundary controlled by flexoelectric interaction. Nat. Commun. 3, 775 (2012).

Holakovsky, J. A new type of the ferroelectric phase transition. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 56, 615–619 (1973).

Kornev, I. A. & Bellaiche, L. Nature of the ferroelectric phase transition in multiferroic BiFeO3 from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 79, 100105 (2009).

Leung, K., Cockayne, E. & Wright, A. F. Effective Hamiltonian study of PbZr0.95Ti0.05O3 . Phys. Rev. B 65, 214111 (2002).

Goian, V. et al. Terahertz and infrared studies of antiferroelectric phase transition in multiferroic Bi0.85Nd0.15FeO3 . J. Appl. Phys. 110, 074112 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Swiss National Science Foundation for funding this project. The research leading to these results was also supported by the European Research Council under the EU 7th Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC grant agreement (268058). This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2010-0010497) and by the National Centre for Science in Poland, grant 1955-B-H03-2011-40. The Research was also supported by Russian Academy of Sciences, Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Grants 11-02-00687 and 13-02-12429) and by grant of the government of the Russian Federation 2012-220-03-434, contract 14.B25.31.0025. We acknowledge the facilities at SPring-8 and the ESRF for their hospitality during the experiments. We also thank Professor Sergei V. Kalinin for an useful discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.S. and A.K.T. initiated the work on the lattice dynamics in PZ. A.K.T. designed the study and conceived the theoretical interpretation of the results. K.V. performed IXS experiment and data treatment. S.B.V. designed the study and performed the IXS and DS experiments, modelled and interpreted the data. A.V.F. performed the IXS and DS experiments. R.G.B. performed the DS experiment and data treatment. D.C. and A.S. performed the DS experiment. D.A. performed the IXS and DS data treatment. A.I.R. coordinated and managed the project from the Russian side. A.Q.R.B. and H.U. performed the IXS experiment. A.B. prepared the samples and interpreted the data of the IXS and DS experiments. PZ single crystals were grown by Z.U. and A.M. J.-H.K. and K.R. performed crystal characterization, Brillouin scattering experiment and data treatment. N.S. coordinated and managed the project from the Swiss side. All co-authors have participated in the discussion of the obtained results. The manuscript was written by A.K.T., S.B.V., R.G.B. and N.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S6, Supplementary Notes 1-8 and Supplementary References (PDF 706 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tagantsev, A., Vaideeswaran, K., Vakhrushev, S. et al. The origin of antiferroelectricity in PbZrO3. Nat Commun 4, 2229 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3229

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3229

This article is cited by

-

A high-temperature double perovskite molecule-based antiferroelectric with excellent anti-breakdown capacity for energy storage

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Brillouin light scattering in niobium doped lead zirconate single crystal

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Continuously tunable ferroelectric domain width down to the single-atomic limit in bismuth tellurite

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Observation of solid-state bidirectional thermal conductivity switching in antiferroelectric lead zirconate (PbZrO3)

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Antiferroelectric negative capacitance from a structural phase transition in zirconia

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.