Abstract

Active nanophotonic devices are attractive due to their low-power consumption, ultrafast modulation speed and high-density integration. Although electrical operation is required for practical implementation of these devices, it is not straightforward to introduce a proper current path into such a wavelength-scale nanostructure without affecting the optical properties. For example, to demonstrate electrically driven nanolasers, complicated fabrication techniques have been used thus far. Here we report an electrically driven microdisk laser using a transparent graphene electrode. Current is injected efficiently through the graphene sheet covering the top surface of the microdisk cavity, and, for the first time, lasing operation was achieved with a low-threshold current of ~300 μA at room temperature. In addition, we measured significant electroluminescence from a graphene-contact subwavelength-scale single nanopillar structure. This work represents a new paradigm for the practical applications of integrated photonic systems, by conformally mounting graphene on the complex surfaces of non-planar three-dimensional nanostructures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graphene electronics/photonics have become an emerging research field because of the excellent electrical/optical properties of graphene1,2. In particular, graphene is promising as a transparent electrode3,4,5 because of its high optical transmittance over a broad range of the spectrum spanning visible and infrared (IR) wavelengths, with a theoretical value of 97.7% for monolayer graphene1,6, as well as remarkably high carrier mobility7. Furthermore, graphene, which possesses unusual mechanical strength and elasticity8,9, can be considered as an alternative to fragile and expensive transparent conducting oxides or thick metals with strong light absorption and scattering properties. Therefore, graphene transparent electrodes have been intensively studied for a broad range of applications, including solar cells10, flexible displays11, touch screens3 and organic light-emitting diodes (LEDs)12.

On the other hand, wavelength-scale nanolasers have been developed, which are promising in that they provide coherent light sources13,14,15,16,17, and can be combined efficiently with other nanophotonic devices, such as waveguides and detectors, for use in ultracompact photonic integrated circuits18,19. To take full advantage of these nanolasers, it is desirable to operate them by electrical injection and achieving this is a critical step for realizing most practical applications of photonic systems. However, it is challenging to inject carriers efficiently in a nanophotonic device because the presence of a carrier path near such an ultrasmall cavity tends to seriously disturb the optical properties of the cavity modes. For this reason, previously reported electrically driven nanolasers require complicated fabrication techniques to place submicron-sized electrodes in a desirable position with a subwavelength-scale accuracy14,15 or to construct lateral p–i–n junctions that are aligned well with a nanocavity13. Several lasers sacrifice the quality (Q) factors of the resonant modes in a cavity directly contacted to a metal electrode, due to metallic absorption, although the mode volumes were further reduced16.

In this study, we demonstrate successfully a microdisk laser and a sub-micrometre-sized single nanopillar LED, which are electrically pumped through the transparent and flexible few-layer graphene electrodes. An optically ultrathin graphene sheet combined with a sensibly designed cavity minimizes the optical loss in the cavity and also provides a robust current path.

Results

Design and fabrication of graphene-contact microdisk laser

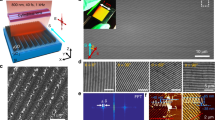

The graphene electrode introduced into our laser device has important roles as an efficient carrier spreading layer as well as an electrode for n-type contact, as shown in the schematic diagram of Fig. 1a. Graphene is contacted on the n–i–p microdisk with three InGaAsP quantum wells and the dielectric material outside the microdisk. This outside dielectric material separates the electrically conductive graphene from the p-doped InP substrate. The p-doped central post is placed underneath the microdisk acting as a p-type electrode14,15. Electrons and holes are then injected through the graphene sheet and central post into the top and bottom layers of the n–i–p microdisk, respectively, and electroluminescence (EL) with a peak wavelength of ~1,550 nm is emitted from the microdisk. In addition, we introduce a dielectric ring structure onto the top of the microdisk, which separates the graphene optically from the boundary of the microdisk, where the whispering-gallery mode (WGM) is highly confined14. As few-layer graphene can cause non-negligible optical absorption20, the dielectric ring structure will be useful to excite the high-Q WGM in the microdisk cavity with the few-layer graphene electrode. Figure 1b shows a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the fabricated graphene-contact microdisk structure. The graphene sheet is well-attached to the surface of the microdisk and suspended freely in air between the microdisk and the outside dielectric material, which is not usually feasible in conventional metal electrodes. Owing to the excellent flexibility and mechanical strength of graphene8,9, the graphene electrode can be mounted conformally on the complex surface of the non-planar three-dimensional (3D) nanostructure, which has a large height variation of 550 nm from the dielectric ring to the microdisk (Supplementary Fig. S1h).

(a) Schematic diagram (not to scale) of a graphene-contact microdisk laser. A few-layer graphene sheet is mounted onto the microdisk with a dielectric ring structure. The dielectric material outside the microdisk separates electrically conductive graphene from the p-InP substrate. (b) SEM image of a fabricated laser structure. The graphene sheet is freely suspended between the microdisk and the outside dielectric material. The scale bar is 1 μm.

We fabricated the graphene-contact microdisk structure using the following procedures (Fig. 2a–d; Supplementary Fig. S1a–g). Representative SEM images of the key fabrication steps are shown in Fig. 2a–d. First, a microdisk with a diameter of ~5 μm is fabricated by electron-beam lithography and dry etching, and a dielectric ring structure is fabricated on the top of the microdisk using cross-linked poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), Fig. 2a. Wet etching in diluted hydrochloric acid solution partially removes the InP sacrificial layer underneath the microdisk, which remains as the post structure for the current path (Fig. 2b). The dielectric material outside the microdisk is defined by electron-beam lithography, again using cross-linked PMMA (Fig. 2c). Finally, the few-layer graphene sheet with the excellent mechanical strength is mounted onto the microdisk and the outside dielectric material (Fig. 2d). As all the fabrication steps are straightforward and simple, the yield is high and the fabricated laser structures are reproducible, as shown in the SEM image of large-area array of the microdisk lasers (Supplementary Fig. S1i). More detailed procedures are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1a–g.

(a–d) Top (upper panel) and tilted (lower panel) views of the SEM images in each fabrication step. (a) The dielectric ring structure was fabricated onto the microdisk. (b) The wet etching defined the central post underneath the microdisk. (c) The outside dielectric material was fabricated around the microdisk. (d) The graphene sheet was mounted onto the microdisk and the outside dielectric material. The scale bars are all 1 μm. (e) The measured transmittance of graphene sheets with two different thicknesses as a function of wavelength (black solid lines). The calculated transmittance curves of graphene sheets with thicknesses of 1.5 and 2.0 nm are also shown (red dotted lines). The inset shows the transmission electron microscopy image of a representative synthesized graphene sheet with five layers (scale bar, 5 nm). (f) The calculated electric field intensity profiles of the WGM (azimuthal number of 24) in the graphene-contact microdisk cavity with the dielectric ring structure. The Q factor and resonant wavelength were calculated to be 2,100 and 1,550 nm, respectively. The left and right panels show side and top views, respectively, in which electric field intensities were normalized by their maximum values. A graphene thickness of 1.5 nm was used in this simulation. The scale bar in the right panel is 1 μm.

Characterization of graphene and numerical simulation

To identify the number of graphene sheets used in our devices, transmission electron microscopy analysis (inset, Fig. 2e) and Raman spectroscopy21 (Supplementary Fig. S2) were performed. These showed that the synthesized graphene sheet has five to ten layers. In addition, to examine the optical properties of graphene, we measured transmittance as a function of wavelength (Fig. 2e). A high transmittance of >91.9% was measured at the peak wavelength of EL (~1,550 nm) and thus the few-layer graphene sheet can be used as a transparent electrode in the near-IR and IR wavelength regions.

To quantitatively analyse optical loss in a graphene-contact microdisk cavity, we calculated the transmittance of the graphene sheet and the optical properties of the cavity mode using 3D finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations (Methods and Supplementary Fig. S3). It is noted that the calculated transmittance of few-layer graphene sheets with different thicknesses of 1.5 and 2.0 nm (red dotted lines, Fig. 2e), which correspond to graphene with five-to-seven layers, agrees well with the experimental results (black solid lines, Fig. 2e). We also calculated the mode profiles and Q factor of the microdisk topped with 1.5-nm-thick graphene, using the structural parameters taken from SEM images of the fabricated device (Fig. 2f). The WGM is well-excited in the graphene-contact microdisk and the electric field is strongly confined at the boundary of the microdisk. As the dielectric ring structure introduced on the top of the microdisk minimizes the optical loss by graphene, a high Q factor of ~2,100 was calculated. This value is ~12 times higher than the calculated Q factor without the dielectric ring structure, which was 170 (Supplementary Fig. S3d). Therefore, the rational cavity design including the dielectric ring structure will be highly useful to avoid undesired absorption loss by few-layer graphene and demonstrate a low-threshold lasing operation.

Measurement of lasing properties

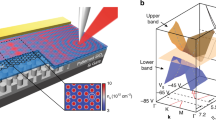

The fabricated microdisk cavity was electrically pumped by using 100 ns current pulses for a period of 1 μs at room temperature. Current was injected using a metal tip, which was contacted the graphene on the dielectric material outside the microdisk (Supplementary Fig. S1j). The light emitted from the microdisk was collected by a ×20 or ×50 long-working-distance microscope objective lens focused onto either a spectrometer or an IR camera (see Methods). As the injected current increased, a sharp, dominant peak was detected along with a rapid increase in intensity. At the further increased current, single-mode lasing was observed at a wavelength of 1,540.5 nm, as shown in Fig. 3a. In addition, the lasing mode image captured by the IR camera shows strong light emission at the boundary of the microdisk cavity (inset, Fig. 3a).

(a) Above-threshold lasing spectrum measured at a peak current of 810 μA. Pulsed current with a 10% duty cycle was injected. Single-mode lasing was observed at a wavelength of 1,540.5 nm. The inset shows the lasing mode image captured by an IR camera at a current of 700 μA (scale bar, 5 μm). (b) Measured lasing intensity as a function of the injected peak current. The threshold current is ~300 μA. The inset shows the current–voltage characteristics of the laser device.

To clearly measure the transition to the lasing mode, we measured the output intensity of the mode as a function of the injected peak current (Fig. 3b). In this plot, a superlinear increase in output intensity can be clearly observed at a low-lasing threshold of ~300 μA. This threshold current is comparable with those of the previously reported microdisk lasers of similar size14,18,19. Analysis of the linewidth as a function of injected current showed a decrease in linewidth to the resolution limit of the spectrometer, ~0.75 nm, as the injected current increases from below to above the threshold current. In this case, the experimental Q factor of the cavity can be estimated to be >2,100, which agrees well with the FDTD simulation result obtained in Fig. 2f. In addition, the electrical properties of the microdisk laser are shown by the voltage versus current curve (inset, Fig. 3b). The turn-on voltage and electrical resistance are ~1.2 V and ~5.8 kΩ, respectively. The relatively high resistance is mainly caused by the contact resistance between the graphene and the InGaAsP material of the microdisk, because the contact resistance is estimated to be ~4.9 kΩ from the result of the transmission line method measurement8 (Supplementary Fig. S4a). This contact resistance can be reduced significantly by introducing a metal layer between the graphene contact and semiconductor material8,22. Indeed, we measured a low device resistance of ~2.3 kΩ using a graphene top contact with a gold layer on the central region of the microdisk (Supplementary Fig. S5). The contact resistance can also be reduced by increasing the doping of the semiconductor or graphene23,24. On the other hand, we note that the graphene contact provides efficient current spreading and uniform current injection into the n-InGaAsP epilayer of the microdisk due to the low sheet resistance of graphene (Supplementary Fig. S4b,c).

We changed the injected current pulse width from 100 to 500 ns for a period of 1 μs to examine the possibility of continuous-wave (CW) lasing operation. Lasing operation was achieved by injection of current pulses with ≤30% duty cycles and showed almost identical threshold currents and lasing wavelengths for each pulse width (Supplementary Fig. S6). However, we could not observe lasing when using a current pulse with a 50% duty cycle, for which significant red shift of the wavelength and linewidth broadening occurred. These observations indicate that the injection of a broad pulse with a >50% duty cycle can cause a significant heat problem in the microdisk with few-layer graphene. Compared with a conventional microdisk cavity with a similar-sized post structure enabling CW lasing operation14,25, the relatively high contact resistance could be a major origin of this thermal issue in the graphene-contact microdisk. In contrast, we measured improved lasing properties from the graphene-contact microdisk laser with a thin gold layer on the central region of the microdisk (Supplementary Fig. S7). Owing to the reduced resistance in this device, lasing operation was successfully achieved by injection of a broad current pulse with a 50% duty cycle. We believe that further improvement of our laser device to reduce the contact resistance will allow us to demonstrate CW lasing operation.

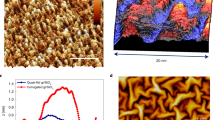

Graphene-contact single nanopillar LED

To take full advantage of the transparent graphene electrode, we carried out electrical pumping in a submicrometer-sized single nanopillar LED. A few-layer graphene sheet was introduced onto a nanopillar structure with a diameter of <500 nm, without the dielectric ring and post structures, as shown in the SEM image of Fig. 4a. The white dotted line indicates the boundary of the dielectric material outside the nanopillar (inset, Fig. 4a). The observed bright spot of the mode image shows significant light emission from the nanopillar (inset, Fig. 4b). The EL spectrum with a peak wavelength of ~1,600 nm was also clearly measured (Fig. 4b). These measurements show that in spite of an ultrasmall size of the nanopillar, the graphene electrode injects current efficiently into the single nanopillar LED. The remarkable demonstration of an electrically driven single nanopillar LED suggests the feasibility of efficient electrical pumping into various nanophotonic devices such as plasmonic lasers26,27, nanowire lasers17 and micro/nanopillar devices28,29.

(a) SEM image of a nanopillar LED with a transparent graphene electrode. The scale bar is 300 nm. The inset shows the top view of the structure, where the white dotted line indicates the boundary of the dielectric material outside the nanopillar (scale bar, 300 nm). Dielectric ring and post structures were not fabricated. (b) Measured EL spectrum of the single nanopillar LED at a current of 1,800 μA. The inset shows the EL image captured by an IR camera at 1,500 μA. Pulsed current with a 5% duty cycle was injected. The scale bar is 5 μm.

Discussion

We successfully demonstrated electrically driven microdisk lasers and subwavelength-scale single nanopillar LEDs using a transparent graphene electrode at room temperature. The graphene electrode, which contacts conformally over the complicated nanostructured surfaces and is also freely suspended in air, is unique and distinguishable from the conventionally used metal electrodes. The use of graphene as a transparent electrode will enrich the applications of graphene in nanophotonic devices and open a new paradigm for the practical applications of ultracompact photonic integrated systems.

Methods

Graphene synthesis

Large-area, few-layer graphene films were synthesized using a home-built chemical vapour deposition system that consists of a horizontal tube furnace8. First, a 200-nm-thick Ni film was deposited on a 200-nm-thick SiO2/Si substrate using a thermal evaporator, and this sample was transferred to the quartz tube reactor. The reactor was evacuated to a pressure well <100 mTorr and filled again with an H2/Ar gas mixture (25% H2 in Ar) until the pressure reached atmospheric pressure. The Ni/SiO2/Si substrate was then annealed at 1,000 °C for 30 min under a H2 and Ar gas mixture at a flow rate of 60 sccm, followed by turning on the flow of methane gas (10 sccm). After resting the sample for 1 min, the methane gas supply was terminated and the chamber was quickly cooled down to room temperature with a cooling rate of ~10 °C s−1 under a continuous H2 and Ar atmosphere. During cooling, carbon atoms were segregated from the Ni film, resulting in the formation of a few-layer graphene sheet.

The synthesized graphene film was coated with a thin protecting layer of PMMA. By submerging the sample in an HF solution, the Ni and SiO2 layers were etched and the PMMA/graphene sheet was separated from the substrate. The remaining Ni layer underneath the PMMA/graphene sheet was additionally removed by an aqueous Ni etchant, TFG, followed by rinsing with water. Then, the hydrophobic PMMA/graphene sheets floated on the water and could be easily moved onto various substrates such as a transmission electron microscopy grid or glass, for structural and optical characterization.

Device fabrication

Microdisk or nanopillar structures were fabricated using (260-nm-thick n–i–p InGaAsP slab)/(1-μm-thick p-InP sacrificial layer)/(p-InP substrate) wafer structure. Three layers of InGaAsP quantum wells are embedded in the slab. The fabrication procedure of the graphene-based cavity structure is shown in detail in Supplementary Fig. S1a–g.

EL measurement

The EL from the graphene-contact microdisk or nanopillar cavity was measured at room temperature by contacting a tungsten tip with a diameter of 1 μm to the graphene sheet mounted on the dielectric material outside the cavity. The sample was attached to an aluminium plate using a conductive silver paste. The forward bias was applied from the aluminium plate to the tungsten tip. We used a pulse generator (Agilent 33521A) and changed the pulse width for a period of 1 μs. The light emitted from the individual microdisk or nanopillar was collected by an ×20 long-working-distance objective lens (with a numerical aperture of 0.4) focused onto either a spectrometer with a resolution limit of ~0.75 nm or an InGaAs IR charge-coupled device camera. The mode image in Fig. 3a was captured by an IR camera using a ×50 long-working-distance objective lens with a numerical aperture of 0.42.

FDTD calculations

In the 3D FDTD simulation, refractive indices of graphite were used to represent few-layer graphene sheets. The graphite was modelled by the Drude critical points (D-CP) model, which can model dispersive material over a wide spectrum30,31:

where

in which  is the background dielectric constant at infinite frequency, ω is the angular frequency, ωD and ωp are the electron plasma frequencies, γD and γp are the effective collision frequencies, φp is the phase, Ap is the weighting coefficient and p is number of critical poles. The D-CP model fits the experimentally determined dielectric functions of graphite in the near-IR and visible spectral range (0.2–1.4 eV) (ref. 32)32. Parameters used in our simulations were as follows:

is the background dielectric constant at infinite frequency, ω is the angular frequency, ωD and ωp are the electron plasma frequencies, γD and γp are the effective collision frequencies, φp is the phase, Ap is the weighting coefficient and p is number of critical poles. The D-CP model fits the experimentally determined dielectric functions of graphite in the near-IR and visible spectral range (0.2–1.4 eV) (ref. 32)32. Parameters used in our simulations were as follows:  =4.53, ωD=8.31 eV, γD=10.86 eV, ωp1=1.07, γp1=0.17 eV, Ap1=−0.53, φp1=0.078 rad, ωp2=0.30 eV, γp2=0.35 eV, Ap2=−10.28, φp2=0.99 rad, where two critical poles were assumed. The D-CP model with the parameters for graphite fits the experimental measured refractive indices over a broad range of spectrum as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3b.

=4.53, ωD=8.31 eV, γD=10.86 eV, ωp1=1.07, γp1=0.17 eV, Ap1=−0.53, φp1=0.078 rad, ωp2=0.30 eV, γp2=0.35 eV, Ap2=−10.28, φp2=0.99 rad, where two critical poles were assumed. The D-CP model with the parameters for graphite fits the experimental measured refractive indices over a broad range of spectrum as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3b.

To represent nanometer-scale graphene sheets, vertical mesh size of 0.5 nm was used. Because of a relatively large horizontal size of microdisk, horizontal mesh size of 10 nm was used to save computational memory. The refractive indices of the InGaAsP microdisk and the PMMA layer were set to 3.4 and 1.5, respectively, in the 3D FDTD simulation. The uniaxial perfectly matched layer was used for the appropriate absorbing boundary condition33.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Kim, Y.-H. et al. Graphene-contact electrically driven microdisk lasers. Nat. Commun. 3:1123 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2137 (2012).

References

Bonaccorso, F., Sun, Z., Hasan, T. & Ferrari, A. C. Graphene photonics and optoelectronics. Nat. Photon. 4, 611–622 (2010).

Park, J. -U., Nam, S., Lee, M. -S. & Lieber, C. M. Synthesis of monolithic graphene-graphite integrated electronics. Nat. Mater. 11, 120–125 (2012).

Bae, S. et al. Roll-to-roll production of 30-inch graphene films for transparent electrodes. Nat. Nanotech. 5, 574–578 (2010).

Kim, K. S. et al. Large-scale pattern growth of graphene films for stretchable transparent electrodes. Nature 457, 706–710 (2009).

Rogers, J. A. Electronic materials: making graphene for macroelectronics. Nat. Nanotech. 3, 254–255 (2008).

Kuzmenko, A. B., van Heumen, E., Carbone, F. & van der Marel, D. Universal optical conductance of graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 117401 (2008).

Du, X., Skachko, I., Barker, A. & Andrei, E. Y. Approaching ballistic transport in suspended graphene. Nat. Nanotech. 3, 491–495 (2008).

Lee, J. M. et al. Vertical pillar-superlattice array and graphene hybrid light emitting diodes. Nano Lett. 10, 2783–2788 (2010).

Lee, C., Wei, X., Kysar, J. W. & Hone, J. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science 321, 385–388 (2008).

Wang, X. et al. Transparent carbon films as electrodes in organic solar cells. Angew. Chem. 120, 3032–3034 (2008).

Zhu, Y., Sun, Z., Yan, Z., Jin, Z. & Tour, J. M. Rational design of hybrid graphene films for high-performance transparent electrodes. ACS Nano 5, 6472–6479 (2011).

Wu, J. et al. Organic light-emitting diodes on solution-processed graphene transparent electrodes. ACS Nano 4, 43–48 (2010).

Ellis, B. et al. Ultralow-threshold electrically pumped quantum-dot photonic-crystal nanocavity laser. Nat. Photon. 5, 297–300 (2011).

Fujita, M., Sakai, A. & Baba, T. Ultrasmall and ultralow threshold GaInAsP–InP microdisk injection lasers: Design, fabrication, lasing characteristics, and spontaneous emission factor. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. Electron. 5, 673–681 (1999).

Park, H. -G. et al. Electrically driven single-cell photonic crystal laser. Science 305, 1444–1447 (2004).

Hill, M. T. et al. Lasing in metallic-coated nanocavities. Nat. Photon. 1, 589–594 (2007).

Duan, X., Huang, Y., Agarwal, R. & Lieber, C. M. Single-nanowire electrically driven lasers. Nature 421, 241–245 (2003).

Liu, L. et al. An ultra-small, low-power, all-optical flip-flop memory on a silicon chip. Nat. Photon. 4, 182–187 (2010).

Campenhout, J. V. et al. Low-footprint optical interconnect on an SOI chip through heterogeneous integration of InP-based microdisk lasers and microdetectors. IEEE Photon. Tech. Lett. 21, 522–524 (2009).

Casiraghi, C. et al. Rayleigh imaging of graphene and graphene layers. Nano Lett. 7, 2711–2717 (2007).

Ni, Z. H. et al. Graphene thickness determination using reflection and contrast spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 7, 2758–2763 (2007).

Gan, Y., Sun, L. & Banhart, F. One- and two-dimensional diffusion of metal atoms in graphene. Small 4, 587–591 (2008).

Shi, Y. et al. Work function engineering of graphene electrode via chemical doping. ACS Nano 4, 2689–2694 (2010).

Chandramohan, S. et al. Work-function-tuned multilayer graphene as current spreading electrode in blue light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 023502 (2012).

Baba, T. Photonic crystals and microdisk cavities based on GaInAsP–InP system. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. Electron. 3, 808–830 (1997).

Kwon, S. -H. et al. Subwavelength plasmonic lasing from a semiconductor nanodisk with silver nanopan cavity. Nano Lett. 10, 3679–3683 (2010).

Ma, R. -M., Oulton, R. F., Sorger, V. J., Bartal, G. & Zhang, X. Room-temperature sub-diffraction-limited plasmon laser by total internal reflection. Nat. Mater. 10, 110–113 (2011).

Heindel, T. et al. Electrically driven quantum dot-micropillar single photon source with 34% overall efficiency. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 011107 (2010).

Fan, Z. et al. Three-dimensional nanopillar-array photovoltaics on low-cost and flexible substrates. Nat. Mater. 8, 648–653 (2009).

Vial, A. Implementation of the critical points model in the recursive convolution method for modelling dispersive media with the finite-difference time domain method. J. Opt. A: Pure Appl. Opt. 9, 745–748 (2007).

Vial, A. & Laroche, T. Description of dispersion properties of metals by means of the critical points model and application to the study of resonant structures using the FDTD method. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 40, 7152–7158 (2007).

Palik, E. D. Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids (Academic Press, San Diego, 1985).

Taflove, A. & Hagness, S. C. Computational Electrodynamics: The Finite-Difference Time-Domain Method 2nd edn (Artech House: Boston, 2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Y.-H. Lee, Dr K.-Y. Jeong and Y.-S. No for preparing samples. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government (NRF/MEST; Grant no. 2012-0000242).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.-H.K., S.-H.K., W.I.P. and H.-G.P. designed the experiment and wrote the paper. Y.-H.K., M.-S.H. and J.-H.K. performed device fabrication and optical experiments. S.-H.K. performed FDTD simulations. J.M.L. and W.I.P. performed synthesis and characterization of graphene. H.-G.P. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S7 (PDF 466 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, YH., Kwon, SH., Lee, J. et al. Graphene-contact electrically driven microdisk lasers. Nat Commun 3, 1123 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2137

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2137

This article is cited by

-

Room temperature electrically pumped topological insulator lasers

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Anapole nanolasers for mode-locking and ultrafast pulse generation

Nature Communications (2017)

-

Chemical and biological sensors based on defect-engineered graphene mesh field-effect transistors

Nano Convergence (2016)

-

Design of plasmonic cavities

Nano Convergence (2014)

-

Room temperature continuous–wave green lasing from an InGaN microdisk on silicon

Scientific Reports (2014)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.