Abstract

Quantum precision enhancement is of fundamental importance for the development of advanced metrological optical experiments, such as gravitational wave detection and frequency calibration with atomic clocks. Precision in these experiments is strongly limited by the 1/√N shot noise factor with N being the number of probes (photons, atoms) employed in the experiment. Quantum theory provides tools to overcome the bound by using entangled probes. In an idealized scenario this gives rise to the Heisenberg scaling of precision 1/N. Here we show that when decoherence is taken into account, the maximal possible quantum enhancement in the asymptotic limit of infinite N amounts generically to a constant factor rather than quadratic improvement. We provide efficient and intuitive tools for deriving the bounds based on the geometry of quantum channels and semi-definite programming. We apply these tools to derive bounds for models of decoherence relevant for metrological applications including: depolarization, dephasing, spontaneous emission and photon loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum-enhanced metrology aims to exploit quantum features of atoms and light such as entanglement, for measuring physical quantities with precision going beyond the classical limit1,2,3,4. A prominent example is that of an optical interferometer, where interference of photons at the output port carries information on the relative optical path difference between the interferometer arms. When standard laser light is used, the observed results are compatible with the claim that 'each photon interferes only with itself'5 and the whole process may be regarded as sensing with N independent probes (photons). Parameter estimation with N independent probes yields the  'standard scaling' (SS) of precision6. Entangling the probes however, can in principle offer a quadratic enhancement in precision, that is, the 1/N or 'Heisenberg scaling' (HS)7,8,9,10,11. Such strategies have been experimentally realized in optical interferometry12,13,14,15,16 with exciting applications in the quest for the first direct detection of gravitational waves17,18. Moreover, the same quantum enhancement principle can be utilized in atomic spectroscopy19,20 where the spin-squeezed states have been employed for improving frequency calibration precision21,22,23,24. Alternative approaches to beat the SS without resorting to quantum entanglement include multiple-pass25,26 and non-linear metrology27,28.

'standard scaling' (SS) of precision6. Entangling the probes however, can in principle offer a quadratic enhancement in precision, that is, the 1/N or 'Heisenberg scaling' (HS)7,8,9,10,11. Such strategies have been experimentally realized in optical interferometry12,13,14,15,16 with exciting applications in the quest for the first direct detection of gravitational waves17,18. Moreover, the same quantum enhancement principle can be utilized in atomic spectroscopy19,20 where the spin-squeezed states have been employed for improving frequency calibration precision21,22,23,24. Alternative approaches to beat the SS without resorting to quantum entanglement include multiple-pass25,26 and non-linear metrology27,28.

Unfortunately, both the theory29,30,31,32,33,34,35 and experiments36,37 confirmed the fragility of the above schemes when noise sources such as decoherence are considered, and it has been rigorously shown for particular models that asymptotically with respect to N, even infinitesimally small noise turns HS into SS, so that the quantum gain amounts to a constant factor improvement38,39,40.

In this paper, we develop two methods that allow us to extend these partial results to a broad class of decoherence models, and in particular to obtain fundamental bounds on quantum enhancement for the most relevant models encountered in the quantum metrology literature. The two approaches complement each other in terms of provided intuition and power. The first method elaborates on the idea of 'classical simulation' (CS)41 and provides a bound based solely on the geometry of the space of quantum channels (SQC). When applicable, it gives an excellent intuition as to why the HS is lost in the presence of decoherence, but fails to yield useful bounds for some relevant decoherence models. The second method is based on the 'channel extension' (CE) strategy42 and requires the optimization over different Kraus representation of a quantum channel. However, unlike the earlier work40, which involved making an educated guess about the appropriate class of Kraus representations, our bound can be cast into an explicit semi-definite optimization problem, which is easy to solve even for complex models. The power of the method is demonstrated by obtaining new bounds for depolarization and spontaneous emission models, and re-deriving asymptotic bounds for dephasing and lossy interferometer with unprecedented simplicity.

Results

Bounds on precision in quantum-enhanced metrology

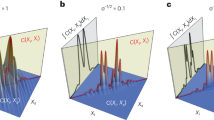

The typical quantum metrology scenario is depicted in Fig. 1a. An ensemble of N quantum systems undergo in parallel the same transformation Λϕ , which depends on an unknown physical parameter ϕ. The output state is measured and the outcome is used to compute an estimate  of the parameter ϕ as summarized below

of the parameter ϕ as summarized below

(a) General scheme for quantum-enhanced metrology. N-probe quantum state fed into N parallel channels is sensing an unknown channel parameter ϕ. An estimator  is inferred from a measurement result on the output state. (b) CS of a quantum channel. The channel Λϕ is interpreted as a mixture of other channels ΛX, where the dependence on ϕ is moved into the mixing probabilities pϕ(X).

is inferred from a measurement result on the output state. (b) CS of a quantum channel. The channel Λϕ is interpreted as a mixture of other channels ΛX, where the dependence on ϕ is moved into the mixing probabilities pϕ(X).

The task is to find the optimal (possibly highly entangled) input state ρN and the most effective measurement strategy to minimize the estimation error ΔϕN. Note that since the decoherence process is assumed to act independently on each of the probes, the global channel is described by the tensor product  .

.

We pursue the estimation problem by restricting our attention to estimators, which are unbiased in the neighbourhood of some fixed parameter value, for which the quantum Cramér–Rao bound (CRB) holds

where FQ is the quantum Fisher information (QFI)9. Maximization of QFI over input states ρN sets the limit on the achievable quantum-enhanced precision:

The states that maximize the QFI and yield the HS for decoherence-free unitary channels are typically highly entangled: the GHZ state in the case of atomic spectroscopy43, and the N00N state in the case of optical interferometry44. In the presence of decoherence, the optimal input states do not have an intuitive form and the maximization of the QFI (with rising N) becomes hard even numerically20,29,30.

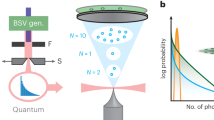

The typical behaviour of the estimation uncertainty in the presence of decoherence is depicted in the log–log scale in Fig. 2, showing that asymptotically in N the quantum gain amounts to a constant factor improvement over the standard  scaling achievable with independent probes. The key result of this paper is to provide a method for a general and simple calculation of this constant factor improvement.

scaling achievable with independent probes. The key result of this paper is to provide a method for a general and simple calculation of this constant factor improvement.

Log–log plot of a generic dependence of quantum-enhanced parameter estimation uncertainty in the presence of decoherence as a function of the number of probes used. While for small number of probes the curve for achievable precision follows the Heisenberg scaling, it asymptotically flattens to approach  dependence. The 'const' represents the quantum enhancement factor. The exemplary data corresponds to the case of phase estimation using N photons in a Mach–Zehnder interferometer with 5% losses in both arms.

dependence. The 'const' represents the quantum enhancement factor. The exemplary data corresponds to the case of phase estimation using N photons in a Mach–Zehnder interferometer with 5% losses in both arms.

Classical simulation

To understand the idea of CS, we need to think of quantum channels in a geometrical way45. A quantum channel is a completely positive, trace-preserving map acting on density matrices. The space of all such transformations is convex: if Λ, Λ′ are two channels, then pΛ+(1−p)Λ′ can be realised by randomly applying Λ or Λ′ with probabilities p and 1−p. The channels that cannot be decomposed into a convex combination of different channels (for example, the unitary transformations) are called 'extremal'. Note that while all interior points of the SQC are 'non-extremal', the boundary contains both the extremal as well as some non-extremal channels.

We say that the family Λϕ is 'classically simulated'41 if each channel is written as a classical mixture of the form

where the unknown parameter enters only through the probability distribution pϕ of a random variable X that indicates which channel to pick from the set {Λx} (Fig. 1b). If X1, ..., XN are the independent hidden random variables used to generate the parallel channels, we can rewrite the estimation problem as

Since conditionally on the values of Xi the output state does not carry any information about ϕ, the estimation precision in the above scenario is at most equal to that of the classical problem of estimating ϕ given N independent samples from the distribution pϕ

Hence, using the classical CRB46, we obtain a lower bound on the uncertainty of the original problem equation (1)

where Fcl is the classical Fisher information; see Methods for an alternative derivation.Provided that pϕ(x) satisfies regularity conditions required in the derivation of CRB46, the SS of precision follows immediately. Moreover, any particular CS yields an explicit SS bound on precision. If many CSs are possible, we obtain the tightest SS bound for ΔϕN by choosing the 'worst' decomposition yielding minimal Fcl[pϕ], as shown below. On the other hand, HS is possible only when the above conditions are not satisfied. This happens, for example, in the decoherence-free case where Λϕ are unitary channels, which are extremal points of the SQC and the only admissible pϕ in equation (4) is the irregular Dirac delta distribution being zero on all channels except Λϕ .

The QFI at a given ϕ0 depends only on the output state and its first derivative at ϕ0. This implies that any family of channels  , which 'locally coincides' with the original one, that is,

, which 'locally coincides' with the original one, that is,

achieves the same maximum QFI in equation (3). It is therefore enough to consider the 'local classical simulations', that is, any mixtures reproducing the channel and its first derivative at given ϕ0. As proven in Supplementary Methods, the CS with the smallest Fcl can be constructed using two channels, {Λ+, Λ−}, which lie on the tangent line to the 'channel trajectory' at the two outermost points situated on the boundary of the set of channels (Fig. 3). The local CS around ϕ0 reads explicitly

Schematic representation of a local classical stimulation (CS) of a channel Λϕ at ϕ0 that lies inside the convex set of quantum channels (solid oval). The optimal CS has to be valid only in the neighbourhood of  along the curve

along the curve  (solid arched line) and corresponds to a binary mixture of channels Λ±, which rest on the tangent (dashed) line at the two outermost points. Then, the precision of estimation can be lower bounded just using the distances ɛ±.

(solid arched line) and corresponds to a binary mixture of channels Λ±, which rest on the tangent (dashed) line at the two outermost points. Then, the precision of estimation can be lower bounded just using the distances ɛ±.

with

Making use of equation (7) applied to the binary probability distribution  , we obtain

, we obtain

To calculate the above bound it suffices to find the 'distances' ɛ± of the channel from the boundary measured along the tangent line. For extremal channels, ɛ±=0 and the bound is not useful. For non-extremal channels, the above construction will yield a finite Fcl provided that ɛ±>0, that is,  can be decomposed into a mixture of channels lying on the tangent. Channels that have this additional property will be called 'ϕ-non-extremal'. They obey the standard precision scaling, and include all full-rank channels (that is, channels lying in the interior of the SQC)41,42. An explicit method for calculating ɛ± and hence the bound for a general quantum channel is described in the Methods.

can be decomposed into a mixture of channels lying on the tangent. Channels that have this additional property will be called 'ϕ-non-extremal'. They obey the standard precision scaling, and include all full-rank channels (that is, channels lying in the interior of the SQC)41,42. An explicit method for calculating ɛ± and hence the bound for a general quantum channel is described in the Methods.

Channel extension

Even though the CS method is very general, there are interesting examples of 'ϕ-extremal' decoherence models for which CS does not apply. In this case, one can resort to the more powerful but less intuitive CE method.

The action of the quantum channel Λϕ can be described via its Kraus representation47:

with Kraus operators satisfying  . Although this representation is not unique, different sets of linearly independent Kraus operators are related by unitary transformations

. Although this representation is not unique, different sets of linearly independent Kraus operators are related by unitary transformations

where u(ϕ) is a unitary matrix possibly depending on ϕ.

An equivalent definition of the QFI has been proposed40,42

where the minimization is performed over all ϕ differentiable purifications of the output state

For pure input state, different purifications correspond to different equivalent Kraus representations of the channel, as in equation (12). For many quantum metrological models40, one can make an educated guess of a purification and derive excellent input-independent analytical bounds providing the correct asymptotic scaling of precision. Nevertheless, the method may be cumbersome especially when the channel description involves many Kraus operators.

A simpler bound can be derived by exploiting the intuitive observation that allowing the channel to act in a trivial way on an extended space, can only improve the precision of estimation, that is,

This leads to an upper bound on  , which goes around the input state optimization, yielding42:

, which goes around the input state optimization, yielding42:

where ||·|| denotes the operator norm, the minimization is performed over all equivalent Kraus representations of Λϕ , and

where  . For any given ϕ=ϕ0, equation (16) involves only

. For any given ϕ=ϕ0, equation (16) involves only  and its first derivatives at ϕ0. Moreover, the bound is insensitive to changing the Kraus representations with a ϕ-independent u. Therefore, it is enough to parameterize equivalent Kraus representations in equation (12) with a hermitian matrix h, which is generator of u(ϕ)=exp[−ih(ϕ−ϕ0)]. This reduces the optimization problem equation (16) to a minimization over h.

and its first derivatives at ϕ0. Moreover, the bound is insensitive to changing the Kraus representations with a ϕ-independent u. Therefore, it is enough to parameterize equivalent Kraus representations in equation (12) with a hermitian matrix h, which is generator of u(ϕ)=exp[−ih(ϕ−ϕ0)]. This reduces the optimization problem equation (16) to a minimization over h.

As the SS of precision holds when  scales linearly with N, the bound equation (16) implies that a sufficient condition for SS is to find h for which

scales linearly with N, the bound equation (16) implies that a sufficient condition for SS is to find h for which  , or equivalently42:

, or equivalently42:

Here we go a step further and show that in this case we can obtain a quantitative SS bound

where the minimization runs over h satisfying equation (18), and can be formulated as a semi-definite program, as described in the Methods section.

Moreover, it turns out that the bound resulting from finding the global minimum in equation (19) is at least as tight as the one derived using the CS method based on equation (7) (see Supplementary Methods) proving superiority of the CE over the CS method.

Examples

All examples of channels presented below are of the form Λϕ[ρ]=Λ[UϕρUϕ†], that is, a concatenation of a unitary rotation encoding the estimated parameter ϕ and an ϕ-independent decoherence process. Consequently, Ki(ϕ)=KiUϕ, where Ki(ϕ), Ki are the Kraus operators of Λϕ and Λ, respectively. The most relevant models in quantum-enhanced metrology belong to this class, but the methods presented may be applied to more general models as well.

In what follows, we adopt the standard notation where is the 2×2 identity matrix and  are the Pauli operators. We focus on two-level probe systems (qubits) sensing a phase shift modelled using a unitary U(ϕ)=exp[(iσ3ϕ)/2]—rotation of the Bloch ball around the z axis. In the case of atomic clocks' frequency calibration ϕ=δω · t with δω being the detuning between the frequency of the atomic transition and the frequency of driving field, while t is the time of evolution. Even though in practice the parameter to be estimated is δω, we will consider that to be ϕ, to have a unified notation for atomic and optical models. In the case of a two-mode optical interferometer, U(ϕ) is the operator acting on a single photon state, accounting for the accumulated relative phase shift ϕ between the two arms of the interferometer.

are the Pauli operators. We focus on two-level probe systems (qubits) sensing a phase shift modelled using a unitary U(ϕ)=exp[(iσ3ϕ)/2]—rotation of the Bloch ball around the z axis. In the case of atomic clocks' frequency calibration ϕ=δω · t with δω being the detuning between the frequency of the atomic transition and the frequency of driving field, while t is the time of evolution. Even though in practice the parameter to be estimated is δω, we will consider that to be ϕ, to have a unified notation for atomic and optical models. In the case of a two-mode optical interferometer, U(ϕ) is the operator acting on a single photon state, accounting for the accumulated relative phase shift ϕ between the two arms of the interferometer.

We apply the methods to four decoherence processes encountered in quantum-enhanced metrology: two-level atom depolarization, dephasing, spontaneous emission and the photon loss inside the interferometer. These examples will provide us with the full picture of the applicability of the methods discussed in the paper, as their cover all distinct cases from the point of view of the geometry of SQC.

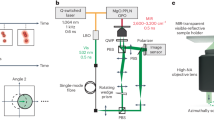

Depolarization

Two-level atom depolarization describes an isotropic loss of coherence and may be visualized by a uniform Bloch ball shrinking (Fig. 4a) where 0≤η<1 is the final Bloch ball radius. Its description involves four Kraus operators

Two-level atom decoherence processes are illustrated with a corresponding shrinking of the Bloch ball (blue) for the cases of: (a) depolarization, (b) dephasing and (c) spontaneous emission. The estimated parameter ϕ represents the angle of rotation about the z axis, whereas η specifies the strength of decoherence and effectively the size of shrinkage in the x–y plane. In the example (d) of the lossy interferometer, ϕ corresponds to the additional phase acquired by photons travelling in the upper arm and η stands for the power transmission coefficient in each of the arms.

which makes it an example of a channel lying in the interior of the SQC. Using CS method, we infer the SS of precision and calculate the 'distances' from the boundary of the SQC  (see Methods) resulting in the bound presented in Table 1. Applying the CE method, it is possible to further improve the bound and the analytical result of the semi-definite optimization is also shown in Table 1. The only non-zero elements of the corresponding optimal h are

(see Methods) resulting in the bound presented in Table 1. Applying the CE method, it is possible to further improve the bound and the analytical result of the semi-definite optimization is also shown in Table 1. The only non-zero elements of the corresponding optimal h are  where c=2(1−η)(1+2η). To our best knowledge, the bound has not been derived before.

where c=2(1−η)(1+2η). To our best knowledge, the bound has not been derived before.

Dephasing

Dephasing is a decoherence model of two-level atoms subject to fluctuating external magnetic/laser fields. In graphical representation, it corresponds to shrinking of the Bloch ball in x, y directions with z direction intact (Fig. 4b). The canonical Kraus operators read47

where 0≤η<1 is the dephasing parameter. As it involves only two Kraus operators, it is not a full-rank channel and lies on the boundary of the SQC. It is, however, a non-extremal and more importantly ϕ-non-extremal channel allowing for the CS construction with  (see Methods), yielding the bound given in Table 1.

(see Methods), yielding the bound given in Table 1.

Most importantly, the above bound, is exactly the same as the one derived by Escher et al.40 or by the CE method, where the minimum in equation (19) corresponds to  . This proves that despite its simplicity the CS method may sometimes lead to bounds that are equally tight as the ones derived with much more advanced methods even for channels lying on the boundary of the SQC.

. This proves that despite its simplicity the CS method may sometimes lead to bounds that are equally tight as the ones derived with much more advanced methods even for channels lying on the boundary of the SQC.

Spontaneous emission

The well-known two-level atom spontaneous emission model is described by the Kraus operators

with 0≤η<1. Interestingly, for all η this channel is extremal48, which means that the CS is not applicable. Nevertheless, the CE method of equation (19) can be easily employed.

Substituting Ki(ϕ) into equation (18), we find that the generator h is fixed to  . Consequently, there is no need for minimization over h and from equation (19) we automatically obtain an SS bound listed in Table 1, which to our knowledge has not been reported in the literature before.

. Consequently, there is no need for minimization over h and from equation (19) we automatically obtain an SS bound listed in Table 1, which to our knowledge has not been reported in the literature before.

Lossy interferometer

To model 'loss' in an optical interferometer, a third orthogonal state at the output,—vacuum—resulting from a loss of a photon, needs to be introduced. The decoherence channel on a single probe (single photon) is a map from a two- to a three-dimensional system:

where η is the power transmission coefficient for the light travelling through each of the two arms. Although the corresponding channel Λϕ is non-extremal, it is unfortunately ϕ-extremal and CS cannot be used. Still, CE method can be easily applied. The optimal bound (see Table 1) corresponds to h with non-zero elements  . This bound is asymptotically equally tight to the best bounds known in the literature38,39,40, proving again that CE method despite its simplicity is able to provide powerful results in a straightforward manner.

. This bound is asymptotically equally tight to the best bounds known in the literature38,39,40, proving again that CE method despite its simplicity is able to provide powerful results in a straightforward manner.

In optical interferometric applications, it is common to use states of light with an unbounded number of photons, such as coherent or squeezed states49,50,51,52,53. At a first glance, it is not obvious that the model considered in the paper covers these situations. Formally speaking, the bound we have derived applies to input states with a total number of photons fixed to N. Notice, however, that in every optical experiment what is measured in the end are photon numbers. If all phase reference beams are taken into account, we can regard quantum states of light as incoherent mixtures of states occupying different total photon number sectors53,54. From the point of view of metrology, the QFI is then bounded from above by the weighted sum of QFIs for each of these sectors30. Within each sector we can easily apply our bound and, as the bound is linear in N, the effective bound will simply correspond to replacing N with  —the mean number of photons in all relevant beams used in the experiment—and as such can be automatically applied to experiments involving coherent and squeezed light.

—the mean number of photons in all relevant beams used in the experiment—and as such can be automatically applied to experiments involving coherent and squeezed light.

To demonstrate the practical relevance of the bound, it is instructive to compare its predictions with the actual quantum enhancement observed recently in the GEO600 gravitational wave detector17. Although a detailed theoretical analysis of the set-up from the perspective of the derived bounds is still underway, by reducing the essential features of the set-up to a simple Mach–Zehnder interferometer, we can already give a preliminary estimate on how far is the actual experiment from the optimal performance. For the reported overall optical transmission η=0.62, the theoretically predicted maximal quantum enhancement amounts to a  factor reduction in estimation uncertainty compared with the classical

factor reduction in estimation uncertainty compared with the classical  limit. The reported experimentally observed reduction was a factor of 0.67, which is an indication that the experiment operates close to the fundamental quantum limit and any significant improvement is possible only if the optical loss is further reduced.

limit. The reported experimentally observed reduction was a factor of 0.67, which is an indication that the experiment operates close to the fundamental quantum limit and any significant improvement is possible only if the optical loss is further reduced.

Discussion

Assessing the impact of decoherence on the maximum possible quantum enhancement is a crucial element in developing quantum techniques for metrological applications. The tools developed here allow for a direct calculation of bounds on the precision enhancement for arbitrary parameter estimation model where the decoherence process acts independently on each of the probes and may be represented with a finite number of Kraus operators. The CE method is more powerful and for the most relevant metrological models yields in the asymptotic limit of large number of probes the tightest bounds known in the literature. Yet the CS method, which may fail to provide equally tight bounds, provides an intuitive geometric insight into the absence of asymptotic HS in the presence of decoherence. From the derived bounds, it is clear that if the HS was to be preserved for large number of probes N the level of decoherence would have to decrease with increasing N roughly as (1−η)≈1/N. This gives an estimate on the regime in which the quantum enhancement is quadratic as compared with the regime of constant factor improvement. This is clearly seen in Fig. 2 where this transition appears around N≈1/(1−η)=20 for η=0.95. As in most metrology applications N is larger by several order of magnitude, we expect that the SS scaling provides a reliable bound for the optimal estimation precision.

An important question that was not addressed here is the saturability of the bounds. The CS method does not provide tight bounds in general. As for the CE method, we are not able to prove that the bounds we have derived are saturable in the asymptotic limit. We should stress however, that these are lower bounds on estimation uncertainties and an upper bound can always be found by choosing a particular estimation method. Therefore, if a certain strategy performs close to the derived bound, we can certify that it is not far from reaching the fundamental quantum limit, as illustrated by the results of the GEO600 experiment.

Even though the minimization over purification method40 yields in principle a tight bound, in practice there is no effective algorithm to find a global minimum, and the only way to convince oneself that one has achieved the global minimum is again to show that the theoretical lower bound on estimation uncertainty coincides with the performance of a particular estimation strategy.

The methods discussed were focused on deriving useful bounds in the asymptotic regime of a large number of probes. Still, the bounds are valid (though weaker) for any value of N. We leave it for a future work to improve the bounds for finite N, which seems to be possible by using the CE method and relaxing the  constraint.

constraint.

Methods

Proof of the CS bound

To simplify the reasoning, let us focus on the CSs that are constructed using discrete sets of quantum channels, {Λi}. Then, the considered channel's action of equation (4) can be rewritten as a ϕ-independent map acting on a larger input space41

where  represents a diagonal state in some basis, in which Φ is defined via

represents a diagonal state in some basis, in which Φ is defined via  with Ei[σ]=〈ei|σ|ei〉. To prove equation (7), we write the QFI for the N parallel use of the channel and bound it from above, that is

with Ei[σ]=〈ei|σ|ei〉. To prove equation (7), we write the QFI for the N parallel use of the channel and bound it from above, that is

exploiting the monotonicity of the QFI under any parameter-independent quantum map55, here  .

.

Calculation of the CS bound

The geometry of the space of channels and more specifically the ϕ-extremality are best viewed by using the Choi–Jamiołkowski isomorphism56,57. Given a quantum channel  acting from the space of density matrices on

acting from the space of density matrices on  to density matrices on

to density matrices on  , one defines

, one defines  , where

, where  is a maximally entangled state in

is a maximally entangled state in  in. Λ is a physical channel (that is, trace preserving, completely positive map) if PΛ is a positive semi-definite operator, satisfying

in. Λ is a physical channel (that is, trace preserving, completely positive map) if PΛ is a positive semi-definite operator, satisfying  . If {Ki}i are the Kraus operators of the Λ channel, we can write explicitly

. If {Ki}i are the Kraus operators of the Λ channel, we can write explicitly  , where

, where  .

.

We can now say that the channel Λϕ is ϕ-non-extremal, if it is possible to find a non-zero ɛ, for which  . See Supplementary Methods for an alternative formulation of the ϕ-non-extremality condition and its relation to the well-known non-extremality condition due to Choi57. In practice, if we want to make most out of the bound in equation (10), we need to find the maximum values of ɛ±, for which

. See Supplementary Methods for an alternative formulation of the ϕ-non-extremality condition and its relation to the well-known non-extremality condition due to Choi57. In practice, if we want to make most out of the bound in equation (10), we need to find the maximum values of ɛ±, for which  are still positive semi-definite operators. This is a simple eigenvalue problem and therefore the bound can be obtained immediately.

are still positive semi-definite operators. This is a simple eigenvalue problem and therefore the bound can be obtained immediately.

Taking the dephasing model as an example, the Choi–Jamiołkowski isomorphism of the corresponding Λϕ channel  has a simple form:

has a simple form:

It is easy to check that  provided

provided  , hence using equation (10) we arrive at the bound given in Table 1.

, hence using equation (10) we arrive at the bound given in Table 1.

CE method as a semi-definite program

Here we show that the minimization problem in equation (19) can be formulated as a simple semi-definite program. Let the channel Λϕ be a map from a d1- to a d2-dimensional Hilbert spaces with Kraus representation involving k linear independent Kraus operators (d2×d1 matrices). Consider the following block matrix:

where is a d×d identity matrix. Positive semi-definiteness of the matrix A is equivalent to the condition

Minimizing the operator norm  is thus equivalent to minimizing t subject to A ≥ 0. Taking into account equation (18), the problem takes the form:

is thus equivalent to minimizing t subject to A ≥ 0. Taking into account equation (18), the problem takes the form:

Since  the matrix A is linear in h and the problem is thus a semi-definite program with the resulting minimal t being the minimal operator norm

the matrix A is linear in h and the problem is thus a semi-definite program with the resulting minimal t being the minimal operator norm  . For the purpose of this paper, we have implemented the program using the CVX package for Matlab58.

. For the purpose of this paper, we have implemented the program using the CVX package for Matlab58.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R. et al. The elusive Heisenberg limit in quantum-enhanced metrology. Nat. Commun. 3:1063 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2067 (2012).

References

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Advances in quantum metrology. Nat. Photon. 5, 222–229 (2011).

Maccone, L. & Giovannetti, V. Quantum metrology: beauty and the noisy beast. Nat. Phys. 7, 376–377 (2011).

Paris, M. G. A. Quantum estimation for quantum technology. Int. J. Quant. Inf. 7, 125–137 (2009).

Banaszek, K., Demkowicz-Dobrzanski, R. & Walmsley, I. A. Quantum states made to measure. Nat. Photon. 3, 673–676 (2009).

Dirac, P. A. M. The Principles of Quantum Mechanics (Oxford University Press, 1958).

Kahn, J. & Guţă, M. Local asymptotic normality for finite dimensional quantum systems. Commun. Math. Phys. 289, 597–652 (2009).

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Quantum-enhanced measurements: beating the standard quantum limit. Science 306, 1330–1336 (2004).

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Quantum metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 010401 (2006).

Braunstein, S. L. & Caves, C. M. Statistical distance and the geometry of quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 3439–3443 (1994).

Berry, D. W. & Wiseman, H. M. Optimal states and almost optimal adaptive measurements for quantum interferometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 5098–5101 (2000).

Zwierz, M., Prez-Delgado, C. A. & Kok, P. General optimality of the heisenberg limit for quantum metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 180402 (2010).

Mitchell, M. W., Lundeen, J. S. & Steinberg, A. M. Super-resolving phase measurements with a multi-photon entangled state. Nature 429, 161–164 (2004).

Eisenberg, H. S., Hodelin, J. F., Khoury, G. & Bouwmeester, D. Multiphoton path entanglement by nonlocal bunching. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 090502 (2005).

Nagata, T., Okamoto, R., O'Brien, J. L., Sasaki, K. & Takeuchi, S. Beating the standard quantum limit with four entangled photons. Science 316, 726–729 (2007).

Resch, K. J. et al. Time-reversal and super-resolving phase measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 223601 (2007).

Higgins, B. L. et al. Demonstrating heisenberg-limited unambiguous phase estimation without adaptive measurements. New J. Phys. 11, 073023 (2009).

LIGO Collaboration.. A gravitational wave observatory operating beyond the quantum shot-noise limit. Nat. Phys. 7, 962–965 (2011).

Goda, K. et al. A quantum-enhanced prototype gravitational-wave detector. Nat. Phys. 4, 472–476 (2008).

Wineland, D. J., Itano, W. M., Bollinger, J. J. & Moore, F. L. Spin squeezing and reduced quantum noise in spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. A 46, R6797–R6800 (1992).

Huelga, S. F. et al. Improvement of frequency standards with quantum entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 3865–3868 (1997).

Meyer, V. et al. Experimental demonstration of entanglement-enhanced rotation angle estimation using trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5870–5873 (2001).

Leibfried, D. et al. Toward heisenberg-limited spectroscopy with multiparticle entangled states. Science 304, 1476–1478 (2004).

Wasilewski, W. et al. Quantum noise limited and entanglement-assisted magnetometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 133601 (2010).

Koschorreck, M., Napolitano, M., Dubost, B. & Mitchell, M. W. Sub-projection-noise sensitivity in broadband atomic magnetometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 093602 (2010).

Higgins, B. L., Berry, D. W., Bartlett, S. D., Wiseman, H. M. & Pryde, G. J. Entanglement-free heisenberg-limited phase estimation. Nature 450, 393–396 (2007).

Demkowicz-Dobrzanski, R. Multi-pass classical versus quantum strategies in lossy phase estimation. Laser Phys. 20, 1197–1202 (2010).

Boixo, S., Flammia, S. T., Caves, S. T. & Geremia, J. M. Generalized limits for single-parameter quantum estimation. Phys. Rev. Lett 98, 090401 (2007).

Napolitano, M. et al. Interaction-based quantum metrology showing scaling beyond the Heisenberg limit. Nature 471, 486–489 (2011).

Dorner, U. et al. Optimal quantum phase estimation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 040403 (2009).

Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R. et al. Quantum phase estimation with lossy interferometers. Phys. Rev. A 80, 013825 (2009).

Shaji, A. & Caves, C. M. Qubit metrology and decoherence. Phys. Rev. A 76, 032111 (2007).

Andrè, A., Sorensen, A. S. & Lukin, M. D. Stability of atomic clocks based on entangled atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 230801 (2004).

Meiser, D. & Holland, M. J. Robustness of heisenberg-limited interferometry with balanced fock states. New J. Phys. 11, 033002 (2009).

Zhengfeng, J., Guoming, W., Runyao, D., Yuan, F. & Mingsheng, Y. Parameter estimation of quantum channels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 54, 5172–5185 (2008).

Datta, A. et al. Quantum metrology with imperfect states and detectors. Phys. Rev. A 83, 063836 (2011).

Kacprowicz, M., Demkowicz-Dobrzanski, R., Wasilewski, W., Banaszek, K. & Walmsley, I. A. Experimental quantum enhanced phase-estimation in the presence of loss. Nat. Photon. 4, 357–360 (2010).

Thomas-Peter, N. et al. Real-world quantum sensors: evaluating resources for precision measurement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 113603 (2011).

Kołodyński, J. & Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R. Phase estimation without a priori phase knowledge in the presence of loss. Phys, Rev. A 82, 053804 (2010).

Knysh, S., Smelyanskiy, V. N. & Durkin, G. A. Scaling laws for precision in quantum interferometry and the bifurcation landscape of the optimal state. Phys. Rev. A 83, 021804(R) (2011).

Escher, B. M., de Matos Filho, R. L. & Davidovich, L. General framework for estimating the ultimate precision limit in noisy quantum-enhanced metrology. Nat. Phys. 7, 406–411 (2011).

Matsumoto, K. On metric of quantum channel spaces. Preprint at arxiv:1006.0300 (2010).

Fujiwara, A. & Imai, H. A fibre bundle over manifolds of quantum channels and its application to quantum statistics. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 41, 255304 (2008).

Bollinger, J. J., Itano, W. M., Wineland, D. J. & Heinzen, D. J. Optimal frequency measurements with maximally correlated states. Phys. Rev. A 54, R4649–R4652 (1996).

Dowling, J. P. Correlated input-port, matter-wave interferometer: quantum-noise limits to the atom-laser gyroscope. Phys. Rev. A 57, 4736–4746 (1998).

Bengtsson, I. & Zyczkowski, K. Geometry of Quantum States: An Introduction to Quantum Entanglement (Cambridge Univeristy Press, 2006).

Kay, S. M. Fundamentals of Statistical Signal Processing: Estimation Theory, Prentice Hall, 1993.

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computing and Quantum Information (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Ruskai, M. B., Szarek, S. & Werner, E. An analysis of completely-positive trace-preserving maps on 2×2 matrices. Lin. Alg. Appl. 347, 159–187 (2002).

Caves, C. M. Quantum-mechanical noise in an interferometer. Phys. Rev. D. 23, 1693–1708 (1981).

Pezze, L. & Smerzi, A. Mach-Zehnder interferometry at the Heisenberg limit with coherent and squeezed-vacuum light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 073601 (2008).

Genomi, M. G., Olivares, S. & Paris, M. G. A. Optical phase estimation in the presence of phase-diffusion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 153603 (2011).

Pinel, O. et al. Ultimate sensitivity of precision measurements with intense Gaussian quantum light: a multimodal approach. Phys. Rev. A 85, 010101(R) (2012).

Jarzyna, M. & Demkowicz-Dobrzanski, R. Quantum interferometry with and without an external phase reference. Phys. Rev. A 85, 011801(R) (2012).

Molmer, K. Optical coherence: a convenient fiction. Phys. Rev. A 55, 3195 (1996).

Fujiwara, A. Quantum channel identification problem. Phys. Rev. A 63, 042304 (2001).

Jamiolkowski, A. Linear transformations which preserve trace and positive semidefiniteness of operators. Rep. Math. Phys 3, 275–278 (1972).

Choi, M.- D. Completely positive linear maps on complex matrices. Lin. Algebr. Appl. 10, 285–290 (1975).

Grant, M. & Boyd, S. CVX: Matlab software for disciplined convex programming, http://cvxr.com/cvx/ (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Konrad Banaszek for many inspiring discussions and constant support. R.D.-D. and J.K. were supported by the European Commission under the IP project Q-ESSENCE, ERA-NET CHIST-ERA project QUASAR and the Foundation for Polish Science under the TEAM programme. M.G. was supported by the EPSRC Fellowship EP/E052290/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G. conceived the CS method. J.K. developed the CE method and utilized both approaches to obtain the exemplary analytic results. R.D.-D. proved the optimality of local tangent CS, the relation between the methods and formulated the semi-definite programming approach to CE. All authors contributed extensively to the manuscript with the leading input from R.D.-D.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods (PDF 48 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R., Kołodyński, J. & Guţă, M. The elusive Heisenberg limit in quantum-enhanced metrology. Nat Commun 3, 1063 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2067

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2067

This article is cited by

-

Multi-ensemble metrology by programming local rotations with atom movements

Nature Physics (2024)

-

Approaching optimal entangling collective measurements on quantum computing platforms

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Experimental super-Heisenberg quantum metrology with indefinite gate order

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Quantum metrology with imperfect measurements

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Determination of the asymptotic limits of adaptive photon counting measurements for coherent-state optical phase estimation

npj Quantum Information (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.