Abstract

Mother's milk is widely accepted as nutritious and protective to the newborn mammals by providing not only macronutrients but also immune-defensive factors. However, the mechanisms accounting for these benefits are not fully understood. Here we show that maternal very-low-density-lipoprotein (VLDL) receptor deletion in mice causes the production of defective milk containing diminished levels of platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase (PAFAH). As a consequence, the nursing neonates suffer from alopecia, anaemia and growth retardation owing to elevated levels of pro-inflammatory platelet-activating factors. VLDL receptor deletion significantly impairs the expression of phospholipase A2 group 7 (Pla2g7) in macrophages, which decreases PAFAH secretion. Exogenous oral supplementation of neonates with PAFAH effectively rescues the toxicity. These findings not only reveal a novel role of VLDL receptor in suppressing inflammation by maintaining macrophage PAFAH secretion, but also identify the maternal VLDL receptor as a key genetic program that ensures milk quality and protects the newborns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mother's milk protects the nursing newborns by providing immune-defensive factors1, but how this protection is achieved is not well understood. Platelet-activating factors (PAF) represent a class of potent pro-inflammatory lipids that are present in neonates whose immune system is not fully developed, and is elevated in infants suffering inflammatory disorders such as necrotizing enterocolitis1,2. Previous studies in both human and rodents show that milk contains the secreted form of the PAF degradation enzyme platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase (PAFAH), which may be critical to suppress the inflammatory activity in the nursing neonates2,3,4. Nonetheless, how milk PAFAH level is controlled is unknown.

Very-low-density-lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) is a member of the LDL receptor family and is known to regulate triglyceride metabolism5 and brain development6. It has been shown that activation of VLDLR by its ligands such as Reelin (Reln)6,7,8 triggers downstream signalling events that modulate neuronal functions. However, whether and how VLDLR regulates macrophage functions is underexplored. Here we identify a novel anti-inflammatory role of VLDLR in maintaining macrophage PAFAH secretion, and demonstrate its physiological significance in ensuring milk PAFAH levels and protecting the nursing newborns from systemic inflammation.

Results

Maternal VLDLR deletion results in defective milk

We found that the mouse pups nursed by the Vldlr−/− mothers developed a transient alopecia that initiated around postnatal day 16 (P16), and became prominent ~P24 (Fig. 1a), but recovered after weaning to a standard chow diet (~P30). These pups also exhibited growth retardation (Fig. 1b) and anaemia (Fig. 1c) compared with the pups nursed by wild-type (WT) mothers. These symptoms suggested a systemic toxicity that targeted the fast-proliferating cells such as hair follicles and erythrocyte precursors. This phenotype was strictly dependent on the maternal genotype but independent of the paternal or pup genotype, because it only occurred when the mothers were Vldlr−/− regardless of whether the fathers or pups were WT, Vldlr+/− or Vldlr−/−. Furthermore, this phenotype was reversed by cross-fostering the pups between Vldlr−/− and WT mothers starting P1 (Table 1 and Fig. 1d–e), indicating that it resulted from a postnatal defect in lactation rather than a prenatal defect in gestation.

(a–c) Nursing pups from Vldlr−/− mothers exhibited alopecia, growth retardation and anaemia compared with pups from WT control mothers. WT or Vldlr−/− female mice were bred with WT male mice, and the pups (WT or Vldlr+/−, respectively) were analysed at postnatal day 24 (P24) (n=12 from 2 independent litters). (a) A representative image of the hair loss. (b) Pup body weight. (c) Complete blood cell count (CBC) of the pups. RBC, red blood cell; HGB, haemoglobin; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration. (d–e) Cross-fostering reversed the growth retardation and anaemia in the pups (n=2 independent fostering pairs). WT or Vldlr−/− (KO) female mice were bred with WT male mice. On P1, three pups were switched between the KO mother (Vldlr+/− pups) and the WT mother (WT pups), and three pups were left with the original mother as controls. The fostered pups and the original pups were distinguished by ear punch and analysed at P24. (d) Pup body weight. (e) CBC of the pups. B, birth/gestation mother; F, foster/lactation mother; KO, Vldlr−/−. Statistical analyses were performed with Student's t-test and all data are shown as mean±s.d.; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.005; ****P<0.001.

Maternal VLDLR deletion causes neonatal inflammation

The skin of the pups nursed by the Vldlr−/− mothers exhibited hyperplasia and follicular cysts (Fig. 2a), increased leucocyte (CD11b+) infiltration (Fig. 2b), and elevated expression of inflammatory genes including IL-1β, TNFα and COX-2 (Fig. 2c). Moreover, serum level of the inflammatory cytokine TNFα was fourfold higher in the pups nursed by the Vldlr−/− mothers compared with pups nursed by WT mothers (Fig. 2d). These results indicate that the alopecia associated with the neonatal toxicity was triggered by a systemic inflammatory response due to the ingestion of the defective milk from the Vldlr−/− mothers.

(a–c) Defects in the skin of the pups nursed by Vldlr−/− mothers compared with the pups nursed by WT control mothers. (a) H&E staining showed skin hyperplasia and follicular cysts (FC, indicated by arrows). Scale bars, 100 μm. (b) Immuno-fluorescence staining showed leucocyte infiltration in the skin at P19. Skin sections were stained with a FITC-CD11b antibody or FITC-isotype control (to show nonspecific staining of the hair shafts). Scale bars, 100 μm. (c) RT–qPCR analysis showed increased inflammatory gene expression in the skin (n=3). (d) Serum level of TNFα was elevated in the pups nursed by Vldlr−/− mothers compared with the pups nursed by WT control mothers (n=12, P19). The pups nursed by Vldlr−/− mothers were Vldlr+/−, and the pups nursed by WT mothers were WT. Statistical analyses were performed with Student's t-test and are shown as mean±s.d.; *P<0.05; ***P<0.005; ****P<0.001; NS, non-significant.

Increased PAF levels in pups nursed by Vldlr−/− mothers

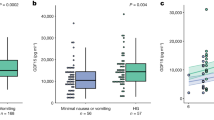

In efforts to pinpoint the biochemical mechanisms underlying the inflammation and hair loss, we performed global metabolomic profiling9,10,11 using untargeted liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS)12,13 to identify the metabolites that were differentially regulated between the skin of the pups nursed by Vldlr−/− mothers and the skin of the pups nursed by WT mothers. We found that a platelet-activating factor (PAF) was significantly increased in the defective skin (2.6-fold) (Supplementary Fig. S1). To further quantify PAF levels in a more specific and sensitive manner, we next performed multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) LC–MS/MS analysis using deuterium-labelled standards as internal controls. The results showed that both PAF-C16 and PAF-C18 were significantly elevated in the skin (Fig. 3a) and the intestine (Fig. 3b) of the pups nursed by Vldlr−/− mothers compared with the pups nursed by WT mothers.

(a,–b) PAF levels were increased in the skin (a) and intestine (b) of the pups nursed by Vldlr−/− mothers compared with the pups nursed by WT control mothers. Tissue lipids were analysed by MRM LC–MS/MS to quantify PAF-C16 (left) and PAF-C18 (right) levels (n=3). The results were normalized to d4-PAF-C16 or d4-PAF-C18 internal control, respectively. P, postnatal day. (c) PAFAH activity was decreased in the milk of Vldlr−/− mothers compared with WT mothers (n=4). (d) PAFAH activity was decreased in the plasma of the pups nursed by Vldlr−/− mothers compared with the pups nursed by WT mothers (n=8). For (a,b,d), the pups nursed by Vldlr−/− mothers were Vldlr+/−, and the pups nursed by WT mothers were WT. (e) PAFAH activity was decreased in the culture medium of Vldlr−/− macrophages compared with WT macrophages that were differentiated from bone marrow (BM) or splenocyte (Sp) (n=4). For e, 1×106 macrophages were differentiated from 1.5×106 bone marrow cells or 5×106 splenocytes of Vldlr−/− mice or WT control mice (male, 3 month old). PAFAH activity was normalized to macrophage cell number (×106). Statistical analyses were performed with Student′s t-test and all data are shown as mean ± s.d.; **P<0.01; ***P<0.005; ****P<0.001.

PAFAH secretion in Vldlr−/− milk is decreased

We next performed ELISA analysis to compare PAFAH activity in the milk. The result demonstrated that PAFAH activity was significantly lower in the milk from Vldlr−/− mothers than in the milk from WT mothers (Fig. 3c). Consistent with this finding, PAFAH activity in the plasma of the pups nursed by Vldlr−/− mothers was also significantly reduced, compared with the pups nursed by WT mothers (Fig. 3d). By contrast, the expression of PAF synthases (Lpcat1 and Lpcat2) was unaltered in the skin and intestine of the pups nursed by Vldlr−/− mothers (Supplementary Fig. S2). This finding suggests that the elevated PAF was caused by decreased degradation by PAFAH rather than increased PAF synthesis. In line with these observations, plasma PAFAH activity was comparable between neonatal Vldlr−/− pups and WT littermate control pups when nursed by the same Vldlr+/− heterozygous mother (Supplementary Fig. S3a), further confirming that neonatal PAFAH is maternal-genotype-dependent and predominantly from milk. After weaning, plasma PAFAH activity was significantly lower in adult Vldlr−/− mice compared with WT controls (Supplementary Fig. S3b), indicating that adult PAFAH is offspring/self-genotype-dependent. Nonetheless, adult Vldlr−/− mice did not develop alopecia, and their serum TNFα level was unaltered (unpublished observation, Y.W.), indicating that inflammation only occurs during nursing, possibly owing to the milk fat intake and the immature gut epithelium/immune system/hair follicle in the neonates.

Because PAFAH in the milk is mainly secreted from macrophages3, we next compared PAFAH activity in the culture medium of macrophages differentiated from bone marrow cells or splenocytes. The results showed that Vldlr−/− bone marrow-derived macrophages secreted 44% less PAFAH, and Vldlr−/− splenocyte-derived macrophages secreted 54% less PAFAH compared with WT macrophages (Fig. 3e).

Decreased Pla2g7 expression in Vldlr−/− macrophage

Because the secreted form of PAFAH is encoded by the Pla2g7 gene14, we next asked whether the diminished PAFAH secretion from Vldlr−/− macrophages was due to reduced Pla2g7 expression. The results showed that comparing with WT macrophages, Pla2g7 messenger RNA levels were 53% and 80% lower in Vldlr−/− macrophages differentiated from bone marrow or splenocyte, respectively (Fig. 4a). By contrast, macrophage expression of PAF synthases (Fig. 4b) or lipoproteins (Supplementary Fig. S4) were unaltered. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of bone marrow and peripheral blood shows that the percentage of macrophages (CD11b+) was similar between adult Vldlr−/− and WT mice (Fig. 4c), indicating that macrophage maturation was unaffected by VLDLR deletion.

(a) Pla2g7 mRNA expression was reduced in Vldlr−/− macrophages compared with WT macrophages (n=4). BM, bone marrow; Sp, spleen. (b) The mRNA expression of PAF synthases, Lpcat1 and Lpcat2, was unaltered in the Vldlr−/− BM macrophages (n=4). For a,b, 1×106 macrophages were differentiated from 1.5×106 bone marrow cells or 5×106 splenocytes of Vldlr−/− mice or WT control mice (male, 3-month-old). (c) FACS analysis of macrophages (CD11b+) in the bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PB) of Vldlr−/− mice and WT control mice (n=3, male, 3 month old). (d) Pla2g7 and Vldlr mRNA levels during a differentiation time course of WT bone marrow macrophages (n=4, male, 3-month-old). The P-values compare the expression on day 8 (d8) or day 12 (d12) with the expression on day 4 (d4). (e) VLDLR knockdown decreases Pla2g7 mRNA expression in human macrophages (n=3). The human monocyte cell line THP-1 was transfected with hVLDLR siRNA (si-VLDLR) or control siRNA (si-Ctrl) for 24 h, and then differentiated into macrophage with TPA (40 ng ml−1) for 48 h. (f) Exogenous VLDLR expression rescues Pla2g7 mRNA expression in Vldlr−/− macrophages (n=3). Bone marrow cells from Vldlr−/− mice (male, 3-month-old) were transfected with VLDLR or vector control for 24 h, and differentiated into macrophage with macrophage colony-stimulating factor for 6 days. (g) Pla2g7 mRNA expression was reduced in Reln−/− macrophages (n=4). Macrophages were differentiated from the bone marrow of 20-day-old Reln−/− (reeler) or WT littermate control mice before the lethality of reeler mice at ~6 week. (h) Pla2g7 mRNA expression was reduced in Dab2-deficient macrophages (n=3). WT bone marrow cells were transfected with Dab2 siRNA (si-Dab2) or control siRNA (si-Ctrl) for 24 h, and then differentiated into macrophages. Statistical analyses were performed with Student's t-test and all data are shown as mean ± s.d. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.005; ****P<0.001; NS, non-significant.

Consistent with these observations, results from the next three experiments further confirm VLDLR regulation of Pla2g7 mRNA expression in macrophage. First, mRNA of Vldlr and Pla2g7 were concurrently increased during a differentiation time course of WT macrophages (Fig. 4d). Second, VLDLR knockdown by small interfering RNA (siRNA) also significantly decreased Pla2g7 expression in the human monocyte THP-1-derived macrophages (Fig. 4e). Third, exogenous VLDLR expression rescued Pla2g7 expression in Vldlr−/− bone marrow macrophages (Fig. 4f). Together, these findings indicate that VLDLR is required for normal Pla2g7 expression in macrophages, and VLDLR deletion reduces PAFAH secretion in the milk.

Regulation of Pla2g7 by VLDLR is mediated by Reln and Dab2

We next explored the ligand and signalling pathway that mediate the VLDLR regulation of Pla2g7 expression in macrophage. Reelin (Reln) is a VLDLR ligand6,7,8 expressed in several cell types in the mammary gland, including epithelium and stroma15,16. We found that Reln was also expressed in macrophages (unpublished observation, Y.W.), suggesting an autocrine regulation of VLDLR signalling. Thus, we compared Pla2g7 expression in Reln−/− and WT macrophages that were differentiated from the bone marrow of 20-day-old (before lethality) reeler mice8 or WT littermate controls. The result shows that Pla2g7 expression was significantly reduced by 38% in the Reln−/− macrophages (Fig. 4g), indicating that Reln is a functional VLDLR ligand in the regulation of Pla2g7.

Both Disabled-1 (Dab1) and Disabled-2 (Dab2) can function as cytoplasmic adaptor proteins to transmit lipoprotein receptor signalling17,18,19. We found that macrophages expressed specifically Dab2, but not Dab1 (unpublished observation, Y.W.). Thus, we examined the effect of siRNA-mediated Dab2 knockdown on Pla2g7 expression in bone marrow macrophages. The result showed that Pla2g7 expression was significantly reduced by 68% in the Dab2-deficient macrophages (Fig. 4h), indicating that Dab2 is an important mediator of VLDLR signalling for the regulation of Pla2g7. On the basis of these evidences, we propose a working model that activation of macrophage VLDLR by ligands such as Reln triggers Dab2-mediated signalling transduction to promote Pla2g7 expression (Fig. 5).

PAFAH feeding to the pups rescues the neonatal toxicity

To further investigate whether the inflammation and toxicity in the pups nursed by the Vldlr−/− mothers was caused by the insufficient levels of PAFAH in the milk, we tested whether the alopecia phenotype could be rescued by exogenous PAFAH supplementation to the pups. Pups from the same Vldlr−/− mother were divided into two groups: the first group was orally gavaged with recombinant human PAFAH (0.15 mg kg−1 day−1) starting P1, and the second group was gavaged with vehicle (PBS) as controls. The results demonstrated that hair loss occurred in all the PBS-treated control pups but was completely prevented in all the PAFAH-treated pups (Fig. 6a). Consistent with this observation, the excessive leucocyte infiltration (Fig. 6b), inflammatory gene expression (Fig. 6c) and PAF accumulation (Fig. 6d) in the control pups were significantly attenuated in the PAFAH-treated pups.

Pups from a Vldlr−/− mother were orally gavaged with recombinant PAFAH at 0.15 mg kg−1 day−1 starting P1 (n=3); as internal controls, pups in the same litter were gavaged with vehicle PBS (n=3). The pups were analysed at P21. (a) A representative image showing the rescue of pup hair loss by PAFAH. (b) Immuno-fluorescence staining showing the reduction of leucocytes (CD11b+) in the pup skin by PAFAH. Scale bars, 100 μm. (c) RT–qPCR analysis showing the attenuated expression of inflammatory genes in the pup skin by PAFAH (n=3). (d) LC–MS/MS analysis showing the reduced levels of PAF-C16 (left) and PAF-C18 (right) in the intestine and skin of the PAFAH-treated pups (n=3). (e) Western blot analyses of PAFAH protein. Left: comparison of two anti-PAFAH antibodies. Representative result of two independent experiments is shown. CM, conditioned medium; m, mouse; h, human; r, recombinant; BMM, bone marrow macrophage. Middle: western blot image for the detection of endogenous (top) and total (bottom) PAFAH in the serum of pups gavaged with PAFAH or PBS control. Right: quantification of the ratio of total/endogenous PAFAH protein in pup serum (n=2). Statistical analyses were performed with Student's t-test and all data are shown as mean±s.d.; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.005.

To quantify PAFAH protein in pup serum, we performed western blot analyses using two antibodies, sc-23021 (G-18) and sc-23022 (E-15). Although both antibodies recognized endogenous human and mouse PAFAH, only E-15, but not G-18, recognized the recombinant human PAFAH (Fig. 6e, left). This allowed us to specifically quantify recombinant human PAFAH using the signal ratio of E15/G18 (total/endogenous PAFAH). The results show that the PAFAH-gavaged pups had a 2.2-fold higher total PAFAH serum level than the PBS-gavaged littermate controls (Fig. 6e, middle and right). This indicates that milk-borne PAFAH can be transmitted to the circulation of the nursing neonates.

Furthermore, supplementation of WT milk with a non-hydrolysable PAF analogue (c-PAF or carbamyl-PAF)20 was sufficient to induce neonatal alopecia (Supplementary Fig. S5a); and supplementation of Vldlr−/− milk with a PAF-receptor antagonist (WEB-2086 or apafant)21 also effectively rescued neonatal alopecia (Supplementary Fig. S5b). Together, these results provide compelling evidence that maternal VLDLR deletion diminishes milk PAFAH level, thereby causing PAF accumulation in the nursing pups, which leads to neonatal inflammation and toxicity.

Discussion

Our findings not only reveal a novel anti-inflammatory role of VLDLR in maintaining macrophage Pla2g7 expression and PAFAH secretion, but also demonstrate its physiological significance in ensuring milk quality and protecting the nursing newborns. First, these studies reveal that maternal PAFAH in the milk is transmitted to the nursing neonates and has a crucial role in their development by preventing excessive inflammation. Thus, our findings have identified PAFAH as a novel and critical immune-defensive factor in the milk. Second, studies from human and rodents show that mutations or dysregulation of VLDLR are often associated with dementia, cerebellar ataxia, mental retardation or dyslipidemia22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. The novel regulation of PAFAH and inflammation by VLDLR may provide new insights to these human diseases. Third, despite the widely reported anti-inflammatory or sometimes pro-inflammatory roles of PAFAH in various physio-pathological contexts2,14,30,31,32,33,34,35, the mechanisms underlying the regulation of Pla2g7 expression are unknown; in particular, a functional control of PAFAH by a lipoprotein receptor has never been demonstrated or hypothesized. Hence, the novel finding that VLDLR promotes macrophage PAFAH production may have broad implications in the aetiology and treatment of neonatal disorders that are associated with inflammation such as necrotizing enterocolitis2,3,4 and atopic dermatitis36, as well as inflammatory diseases in adulthood that are associated with PAF and PAFAH such as Crohn's disease31, atherosclerosis33,35, asthma32,34 and macular degeneration37,38.

Methods

Mice

Vldlr−/− mice39 were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and backcrossed to C57BL/6 for at least three generations. Reeler mice8 were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. For milk and pup analyses, 8—16-weeks-old female Vldlr−/− mice or WT control mice were bred to WT male mice. The litter sizes were normalized to six pups. Mice were fed standard rodent chow ad libitum. Milk was collected as described13. On lactation day 8–12, lactating females were separated from their pups for 3–5 h to allow the mammary glands to refill. Before milking, the lactating female was anaesthetized with an i.p. injection of avertin (0.6 ml of a 20-mg ml−1 stock), and then i.p. injected with 0.5 U of oxytocin (0.2 ml of a 2.5 U ml−1 stock) to induce milk ejection. Milk was immediately collected from mammary glands by gentle vacuum suction through a capillary tube. All ten mammary glands were milked two rounds for a total of 20 min per mouse, allowing the collection of most of the milk. All protocols for mouse experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Reagents

Immuno-fluorescence staining was performed using FITC-anti-CD11b or FITC-isotype-control (1:200) (BD Biosciences). Serum TNFα was measured using a Cytometric Bead Array Mouse Inflammation Kit (BD Biosciences). Complete blood count was performed at Antech Diagnostics. All mRNA expression was measured by RT–qPCR (SYBR Green) in triplicate and normalized by L19 (for mouse) or 36B4 (for human). PAFAH activity was measured by an ELISA kit (Cayman Chemical). For PAFAH rescue experiment, recombinant PAFAH (Antigenix America) was dissolved in PBS and orally gavaged at 0.15 mg kg−1 day−1 starting P1. Anti-PAFAH antibodies (1:500), siRNAs, c-PAF and WEB-2086 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Macrophage differentiation

For macrophage differentiation, bone marrow cells or splenocytes were isolated from Vldlr−/− mice or WT mice, and cultured in α-MEM containing 10% FBS and 20 ng ml−1 macrophage colony-stimulating factor for 12 days with a change of medium every 4 days. On day 12, culture medium was collected for PAFAH activity assay; RNA was collected from the cells for RT–qPCR analysis. THP-1 cells were transfected with hVLDLR siRNA or control siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Life Technologies), and differentiated 24 h later with 40 ng ml−1 TPA for 2 days17.

Lipid analysis by mass spectrometry

For global metabolomic profiling, organic soluble metabolites were extracted from 0.1 g of tissue, subjected to untargeted analysis using an Agilent Accurate-Mass TOF LC–MS instrument under positive and negative ionization mode, and data were analysed using XCMS software for peak alignment and quantification12,13. For PAF LC–MS/MS analysis, d4-PAF-C16 and d4-PAF-C18 standards (Cayman Chemical) were added to each tissue sample at 1 pmol mg−1 before lipid extraction. A Gemini C18 column (Phenomenex) was used for a reverse phase separation of the lipids, with mobile phase A as 0.1% formic acid v/v, and mobile phase B as 100% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid v/v. A gradient elution from 5% B to 100% B was done over 20 min, and held at 100% B for 5 min before a 13-min re-equilibration. MS/MS quantification of PAF-C16, d4-PAF-C16, PAF-C18, d4-PAF-C18 was performed on an Agilent 6410 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer in MRM mode using electrospray ionization in positive ion mode. All of these compounds readily fragmented on activation to a choline ion at m/z=184. An optimum fragmentor voltage of 170 V and collision energy of 24 eV was determined and the following transitions were monitored: PAF-C16 (524.5→184), d4-PAF-C16 (528.5→184), PAF-C18 (552.5→184), d4-PAF-C18 (556.5→184). Integrated peak area for these transitions was used for quantification. The level of each endogenous PAF was normalized by the corresponding deuterium-labelled internal control.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with Student's t-test and represented as mean±s.d.; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.005; ****P<0.001.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Du, Y. et al. Macrophage VLDL receptor promotes PAFAH secretion in mother's milk and suppresses systemic inflammation in nursing neonates. Nat. Commun. 3:1008 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2011 (2012).

References

Walker, A. Breast milk as the gold standard for protective nutrients. J. Pediatr. 156, S3–S7 (2010).

Caplan, M. S., Sun, X. M., Hseuh, W. & Hageman, J. R. Role of platelet activating factor and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J. Pediatr. 116, 960–964 (1990).

Furukawa, M., Narahara, H., Yasuda, K. & Johnston, J. M. Presence of platelet-activating factor-acetylhydrolase in milk. J. Lipid Res. 34, 1603–1609 (1993).

Moya, F. R. et al. Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase in term and preterm human milk: a preliminary report. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 19, 236–239 (1994).

Tacken, P. J., Hofker, M. H., Havekes, L. M. & van Dijk, K. W. Living up to a name: the role of the VLDL receptor in lipid metabolism. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 12, 275–279 (2001).

Trommsdorff, M. et al. Reeler/Disabled-like disruption of neuronal migration in knockout mice lacking the VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2. Cell 97, 689–701 (1999).

D'Arcangelo, G. et al. Reelin is a ligand for lipoprotein receptors. Neuron 24, 471–479 (1999).

D'Arcangelo, G. et al. A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature 374, 719–723 (1995).

Saghatelian, A. & Cravatt, B. F. Global strategies to integrate the proteome and metabolome. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 9, 62–68 (2005).

Saghatelian, A. & Cravatt, B. F. Assignment of protein function in the postgenomic era. Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 130–142 (2005).

Vinayavekhin, N., Homan, E. A. & Saghatelian, A. Exploring disease through metabolomics. ACS Chem. Biol. 5, 91–103 (2010).

Saghatelian, A. et al. Assignment of endogenous substrates to enzymes by global metabolite profiling. Biochemistry 43, 14332–14339 (2004).

Wan, Y. et al. Maternal PPAR gamma protects nursing neonates by suppressing the production of inflammatory milk. Genes Dev. 21, 1895–1908 (2007).

Tjoelker, L. W. et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of a platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase. Nature 374, 549–553 (1995).

Khialeeva, E., Lane, T. F. & Carpenter, E. M. Disruption of reelin signaling alters mammary gland morphogenesis. Development 138, 767–776 (2011).

Stein, T. et al. Loss of reelin expression in breast cancer is epigenetically controlled and associated with poor prognosis. Am. J. Pathol. 177, 2323–2333 (2010).

Trommsdorff, M., Borg, J. P., Margolis, B. & Herz, J. Interaction of cytosolic adaptor proteins with neuronal apolipoprotein E receptors and the amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33556–33560 (1998).

Howell, B. W., Lanier, L. M., Frank, R., Gertler, F. B. & Cooper, J. A. The disabled 1 phosphotyrosine-binding domain binds to the internalization signals of transmembrane glycoproteins and to phospholipids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 5179–5188 (1999).

Morris, S. M. & Cooper, J. A. Disabled-2 colocalizes with the LDLR in clathrin-coated pits and interacts with AP-2. Traffic 2, 111–123 (2001).

Tessner, T. G., O'Flaherty, J. T. & Wykle, R. L. Stimulation of platelet-activating factor synthesis by a nonmetabolizable bioactive analog of platelet-activating factor and influence of arachidonic acid metabolites. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 4794–4799 (1989).

Casals-Stenzel, J., Franke, J., Friedrich, T. & Lichey, J. Bronchial and vascular effects of Paf in the rat isolated lung are completely blocked by WEB 2086, a novel specific Paf antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 91, 799–802 (1987).

Boycott, K. M. et al. Homozygous deletion of the very low density lipoprotein receptor gene causes autosomal recessive cerebellar hypoplasia with cerebral gyral simplification. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 77, 477–483 (2005).

Helbecque, N. et al. VLDL receptor polymorphism, cognitive impairment, and dementia. Neurology 56, 1183–1188 (2001).

Moheb, L. A. et al. Identification of a nonsense mutation in the very low-density lipoprotein receptor gene (VLDLR) in an Iranian family with dysequilibrium syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 16, 270–273 (2008).

Okuizumi, K. et al. Genetic association of the very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) receptor gene with sporadic Alzheimer′s disease. Nat. Genet. 11, 207–209 (1995).

Ozcelik, T. et al. Mutations in the very low-density lipoprotein receptor VLDLR cause cerebellar hypoplasia and quadrupedal locomotion in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 4232–4236 (2008).

Turkmen, S. et al. Cerebellar hypoplasia, with quadrupedal locomotion, caused by mutations in the very low-density lipoprotein receptor gene. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 16, 1070–1074 (2008).

Near, S. E., Wang, J. & Hegele, R. A. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the very low density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) gene. J. Hum. Genet. 46, 490–493 (2001).

Yagyu, H. et al. Very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) receptor-deficient mice have reduced lipoprotein lipase activity. Possible causes of hypertriglyceridemia and reduced body mass with VLDL receptor deficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 10037–10043 (2002).

Claud, E. C., Li, D., Xiao, Y., Caplan, M. S. & Jilling, T. Platelet-activating factor regulates chloride transport in colonic epithelial cell monolayers. Res. 52, 155–162 (2002).

Kald, B., Smedh, K., Olaison, G., Sjodahl, R. & Tagesson, C. Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase activity in intestinal mucosa and plasma of patients with Crohn's disease. Digestion 57, 472–477 (1996).

Miwa, M. et al. Characterization of serum platelet-activating factor (PAF) acetylhydrolase. Correlation between deficiency of serum PAF acetylhydrolase and respiratory symptoms in asthmatic children. J. Clin. Invest. 82, 1983–1991 (1988).

Packard, C. J. et al. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 as an independent predictor of coronary heart disease. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 343, 1148–1155 (2000).

Stafforini, D. M. et al. Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase deficiency. A missense mutation near the active site of an anti-inflammatory phospholipase. J. Clin. Invest. 97, 2784–2791 (1996).

Wilensky, R. L. et al. Inhibition of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 reduces complex coronary atherosclerotic plaque development. Nat. Med. 14, 1059–1066 (2008).

Gdalevich, M., Mimouni, D., David, M. & Mimouni, M. Breast-feeding and the onset of atopic dermatitis in childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 45, 520–527 (2001).

Demos, C., Bandyopadhyay, M. & Rohrer, B. Identification of candidate genes for human retinal degeneration loci using differentially expressed genes from mouse photoreceptor dystrophy models. Mol. Vis. 14, 1639–1649 (2008).

Haines, J. L. et al. Functional candidate genes in age-related macular degeneration: significant association with VEGF, VLDLR, and LRP6. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47, 329–335 (2006).

Frykman, P. K., Brown, M. S., Yamamoto, T., Goldstein, J. L. & Herz, J. Normal plasma lipoproteins and fertility in gene-targeted mice homozygous for a disruption in the gene encoding very low density lipoprotein receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 8453–8457 (1995).

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs John Johnston and Yu-Guang He at UTSW for discussion, UTSW Molecular Pathology Core for histology, Dr Sunia Trauger at the Small Molecule Mass Spectrometry Facility of Harvard FAS Center for Systems Biology for assistance with LC–MS analyses. Y.W. is a Virginia Murchison Linthicum Scholar in Medical Research and a recipient of the Basil O'Connor Scholar Award. A.S. is a recipient of the Burroughs Wellcome Career Award in Biosciences, a Searle Scholar Award and an Alfred P. Sloan Award. This work was supported by March of Dimes Foundation (#5-FY10-1, Y.W.), The Welch Foundation (I-1751, Y.W.), CPRIT (RP100841, Y.W.), NIH (R01 DK089113, Y.W.) and UTSW Endowed Scholar Startup Fund (Y.W.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.D. and M.Y. performed most of the experiments and data analyses. W.W. assisted with ELISA analyses. H.H. assisted with FACS analyses. J.H. contributed to reagents. A.S. assisted with LC–MS analyses. Y.W. conceived the project, designed the experiments, assisted with data analysis and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S5 (PDF 50 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Du, Y., Yang, M., Wei, W. et al. Macrophage VLDL receptor promotes PAFAH secretion in mother's milk and suppresses systemic inflammation in nursing neonates. Nat Commun 3, 1008 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2011

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2011

This article is cited by

-

Identification of RELN variant p.(Ser2486Gly) in an Iranian family with ankylosing spondylitis; the first association of RELN and AS

European Journal of Human Genetics (2020)

-

Molecular determinants for the polarization of macrophage and osteoclast

Seminars in Immunopathology (2019)

-

Salmonella typhimurium-induced M1 macrophage polarization is dependent on the bacterial O antigen

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.